The

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent form ...

committed

war crimes in many Asian-Pacific countries during the period of

Japanese imperialism

This is a list of regions occupied or annexed by the Empire of Japan until 1945, the year of the end of World War II in Asia, after the surrender of Japan. Control over all territories except most of the Japanese mainland (Hokkaido, Honshu, Kyu ...

, primarily during the

Second Sino-Japanese and

Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vas ...

s. These incidents have been described as an "Asian

Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

".

Some war crimes were committed by Japanese

military personnel

Military personnel are members of the state's armed forces. Their roles, pay, and obligations differ according to their military branch (army, navy, marines, air force, space force, and coast guard), rank ( officer, non-commissioned office ...

during the late 19th century, but most were committed during the first part of the

Shōwa era

The was the period of Japanese history corresponding to the reign of Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito) from December 25, 1926, until his death on January 7, 1989. It was preceded by the Taishō era.

The pre-1945 and post-war Shōwa periods are almos ...

, the name given to the reign of

Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother ( ...

Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

.

Under Emperor Hirohito, the

Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emper ...

(IJA) and the

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

(IJN) perpetrated numerous war crimes which resulted in the deaths of millions of people. Estimates of the number of deaths range from three

to 30

million through

massacres

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

,

human experimentation,

starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, de ...

, and

forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

directly perpetrated or condoned by the Japanese military and government. Japanese veterans have admitted war crimes and have provided oral testimonies and written evidence, which includes diaries and war journals.

Airmen

An airman is a member of an air force or air arm of a nation's armed forces. In certain air forces, it can also refer to a specific enlisted rank. An airman can also be referred as a soldier in other definitions.

In civilian aviation usage, ...

of the

Imperial Japanese Army Air Service

The Imperial Japanese Army Air Service (IJAAS) or Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF; ja, 大日本帝國陸軍航空部隊, Dainippon Teikoku Rikugun Kōkūbutai, lit=Greater Japan Empire Army Air Corps) was the aviation force of the Im ...

and

Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service

The was the air arm of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). The organization was responsible for the operation of naval aircraft and the conduct of aerial warfare in the Pacific War.

The Japanese military acquired their first aircraft in 1910 ...

were not charged as war criminals because there was no

positive

Positive is a property of positivity and may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* Positive formula, a logical formula not containing negation

* Positive number, a number that is greater than 0

* Plus sign, the sign "+" used to indicate a posi ...

or specific

customary

Custom, customary, or consuetudinary may refer to:

Traditions, laws, and religion

* Convention (norm), a set of agreed, stipulated or generally accepted rules, norms, standards or criteria, often taking the form of a custom

* Norm (social), a r ...

international humanitarian law

International humanitarian law (IHL), also referred to as the laws of armed conflict, is the law that regulates the conduct of war ('' jus in bello''). It is a branch of international law that seeks to limit the effects of armed conflict by pr ...

that prohibited the unlawful conduct of

aerial warfare

Aerial warfare is the use of military aircraft and other flying machines in warfare. Aerial warfare includes bombers attacking enemy installations or a concentration of enemy troops or strategic targets; fighter aircraft battling for contr ...

either before or during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. The Imperial Japanese Army Air Service took part in conducting

chemical

A chemical substance is a form of matter having constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Some references add that chemical substance cannot be separated into its constituent elements by physical separation methods, i.e., w ...

and

biological attacks on enemy nationals during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II. The use of such weapons was generally prohibited by international agreements previously signed by Japan, including the

Hague Conventions (1899 and 1907)

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions were amo ...

, which banned the use of "poison or poisoned weapons" in warfare.

Since the 1950s, senior Japanese government officials have

issued numerous apologies for the war crimes.

Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs acknowledges Japan's role in causing "tremendous damage and suffering" during World War II, especially during the IJA's entrance into Nanjing, during which Japanese soldiers

killed a large number of non-combatants and engaged in looting and rape.

However, some members of the

Liberal Democratic Party in the Japanese government, such as the former prime ministers

Junichiro Koizumi

Junichiro Koizumi (; , ''Koizumi Jun'ichirō'' ; born 8 January 1942) is a former Japanese politician who was Prime Minister of Japan and President of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) from 2001 to 2006. He retired from politics in 2009. He is ...

and

Shinzō Abe

Shinzo Abe ( ; ja, 安倍 晋三, Hepburn: , ; 21 September 1954 – 8 July 2022) was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan and President of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) from 2006 to 2007 and again from 2012 to 20 ...

, have prayed at the

Yasukuni Shrine

is a Shinto shrine located in Chiyoda, Tokyo. It was founded by Emperor Meiji in June 1869 and commemorates those who died in service of Japan, from the Boshin War of 1868–1869, to the two Sino-Japanese Wars, 1894–1895 and 1937–1945 resp ...

; this has been the subject of

controversy

Controversy is a state of prolonged public dispute or debate, usually concerning a matter of conflicting opinion or point of view. The word was coined from the Latin ''controversia'', as a composite of ''controversus'' – "turned in an opposite d ...

, as the shrine honours all Japanese who died during the war, including convicted

Class A war criminals

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for crimes against peace, conve ...

. Some

Japanese history textbooks offer only brief references to the war crimes, and members of the Liberal Democratic Party have denied some of the atrocities, such as government involvement in abducting women to serve as "

comfort women

Comfort women or comfort girls were women and girls forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army in occupied countries and territories before and during World War II. The term "comfort women" is a translation of the Japanese '' ian ...

", a

euphemism

A euphemism () is an innocuous word or expression used in place of one that is deemed offensive or suggests something unpleasant. Some euphemisms are intended to amuse, while others use bland, inoffensive terms for concepts that the user wishes ...

for

sex slaves

Sexual slavery and sexual exploitation is an attachment of any ownership right over one or more people with the intent of coercing or otherwise forcing them to engage in sexual activities. This includes forced labor, reducing a person to a ...

.

Definitions

The

Tokyo Charter defines

war crimes as "violations of the

laws or customs of war," which includes crimes against enemy

combatants

Combatant is the legal status of an individual who has the right to engage in hostilities during an armed conflict. The legal definition of "combatant" is found at article 43(2) of Additional Protocol I (AP1) to the Geneva Conventions of 1949. It ...

and enemy

non-combatants

Non-combatant is a term of art in the law of war and international humanitarian law to refer to civilians who are not taking a direct part in hostilities; persons, such as combat medics and military chaplains, who are members of the belligeren ...

. War crimes also included deliberate attacks on

citizens

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

and

property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

of

neutral states as they fall under the category of non-combatants, as in the case of the

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

.

Military personnel from the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent form ...

have been convicted of committing many such acts during the period of

Japanese imperialism

This is a list of regions occupied or annexed by the Empire of Japan until 1945, the year of the end of World War II in Asia, after the surrender of Japan. Control over all territories except most of the Japanese mainland (Hokkaido, Honshu, Kyu ...

from the late 19th to mid-20th centuries. Japanese military soldiers conducted a series of

human rights abuse

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hum ...

s against civilians and prisoners of war throughout East Asia and the western

Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

region. These events reached their height during the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific T ...

of 1937–45 and the

Asian and Pacific campaigns of World War II (1941–45).

International and Japanese law

Japan signed the

1929 Geneva Convention on the Prisoners of War and the

1929 Geneva Convention on the Sick and Wounded,

but the Japanese government declined to ratify the POW Convention. In 1942, the Japanese government stated that it would abide by the terms of the Convention ''

mutatis mutandis

''Mutatis mutandis'' is a Medieval Latin phrase meaning "with things changed that should be changed" or "once the necessary changes have been made". It remains unnaturalized in English and is therefore usually italicized in writing. It is used ...

'' ('changing what has to be changed'). The crimes committed also fall under other aspects of international and Japanese law. For example, many of the crimes committed by Japanese personnel during World War II broke Japanese

military law

Military justice (also military law) is the legal system (bodies of law and procedure) that governs the conduct of the active-duty personnel of the armed forces of a country. In some nation-states, civil law and military law are distinct bodie ...

, and were subject to

court martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

, as required by that law. The Empire also violated international agreements signed by Japan, including provisions of the

Hague Conventions (1899 and 1907)

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions were amo ...

such as protections for

prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

and a ban on the use of

chemical weapons

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as a ...

, the

1930 Forced Labour Convention which prohibited

forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

, the

which prohibited

human trafficking

Human trafficking is the trade of humans for the purpose of forced labour, sexual slavery, or commercial sexual exploitation for the trafficker or others. This may encompass providing a spouse in the context of forced marriage, or the extr ...

, and other agreements.

The Japanese government also signed the

Kellogg-Briand Pact (1929), thereby rendering its actions in 1937–45 liable to charges of

crimes against peace

A crime of aggression or crime against peace is the planning, initiation, or execution of a large-scale and serious act of aggression using state military force. The definition and scope of the crime is controversial. The Rome Statute contains an ...

,

a charge that was introduced at the

Tokyo Trials

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for crimes against peace, conv ...

to prosecute "Class A" war criminals. "Class B" war criminals were those found guilty of war crimes ''per se'', and "Class C" war criminals were those guilty of

crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

. The Japanese government also accepted the terms set by the

Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, Uni ...

(1945) after the end of the war, including the provision in Article 10 of punishment for "all war criminals, including those who have visited cruelties upon our prisoners".

Japanese law does not define those convicted in the post-1945 trials as criminals, despite the fact that Japan's governments have accepted the judgments made in the trials, and in the

Treaty of San Francisco

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and including World War II. It w ...

(1952). Former Prime Minister

Shinzō Abe

Shinzo Abe ( ; ja, 安倍 晋三, Hepburn: , ; 21 September 1954 – 8 July 2022) was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan and President of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) from 2006 to 2007 and again from 2012 to 20 ...

had advocated the position that Japan accepted the Tokyo tribunal and its judgements as a condition for ending the war, but that its verdicts have no relation to domestic law. According to Abe, those convicted of war crimes are not criminals under Japanese law.

Historical and geographical extent

Outside Japan, different societies use widely different timeframes when they define Japanese war crimes. For example,

the annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910 was enforced by the Japanese military, and the Society of

Yi Dynasty Korea was switched to the political system of the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent form ...

. Thus,

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

and

South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

both refer to "Japanese war crimes" as events which occurred during the period of

Korea under Japanese rule

Between 1910 and 1945, Korea was ruled as a part of the Empire of Japan. Joseon Korea had come into the Japanese sphere of influence with the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876; a complex coalition of the Meiji government, military, and business off ...

.

By comparison, the

Western Allies

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy ...

did not come into a military conflict with Japan until 1941, and

North Americans

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the C ...

, Australians,

South East Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

ns and Europeans may consider "Japanese war crimes" to be events that occurred from 1942–1945.

Japanese war crimes were not always carried out by

ethnic Japanese personnel. A small minority of people in every Asian and Pacific country invaded or occupied by Japan

collaborated with the Japanese military, or even served in it, for a wide variety of reasons, such as economic hardship, coercion, or antipathy to other

imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power ( economic and ...

powers. In addition to Japanese civil and military personnel, Chinese, Koreans, Manchus and Taiwanese who were forced to serve in the military of the Empire of Japan were also found to have committed war crimes as part of the Japanese Imperial Army.

[Harmsen, Peter, ]Jiji Press

is a news agency in Japan.

History

Jiji was formed in November 1945 following the breakup of Domei Tsushin, the government-controlled news service responsible for disseminating information prior to and during World War II. Jiji inherited Do ...

, "Taiwanese seeks payback for brutal service in Imperial Army", ''The Japan Times

''The Japan Times'' is Japan's largest and oldest English-language daily newspaper. It is published by , a subsidiary of News2u Holdings, Inc.. It is headquartered in the in Kioicho, Chiyoda, Tokyo.

History

''The Japan Times'' was launched b ...

'', 26 September 2012, p. 4

Japan's

sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

over

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

and

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

, in the first half of the 20th century, was recognized by international agreements—the

Treaty of Shimonoseki

The , also known as the Treaty of Maguan () in China and in the period before and during World War II in Japan, was a treaty signed at the , Shimonoseki, Japan on April 17, 1895, between the Empire of Japan and Qing China, ending the Firs ...

of 1895 and the

Japan–Korea Annexation Treaty of 1910—and at the time, they were considered integral parts of the Japanese colonial empire. Under the

international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

of today, the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty might be illegal,

[Yutaka Kawasaki, "Was the 1910 Annexation Treaty Between Korea and Japan Concluded Legally?" ''Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law'', v. 3, no. 2 (July 1996)](_blank)

Access date: 15 February 2007. because the native populations of Korea and Taiwan were not consulted during the signing of them, there was armed resistance to Japan's annexations, and the Japanese may have also committed war crimes when they crushed the resistance.

Background

Japanese militarism, nationalism, imperialism and racism

Militarism

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

,

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

and

racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagoni ...

, especially during Japan's imperialist expansion, had great bearings on the conduct of the Japanese armed forces both before and during the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. After the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

and the collapse of the

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Tokugawa-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia ...

, the

Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother ( ...

became the focus of military loyalty, nationalism and racism. During the so-called "Age of Imperialism" in the late 19th century, Japan followed the lead of other world powers by establishing a colonial empire, an objective which it aggressively pursued.

Unlike many other major powers, Japan never ratified the

Geneva Convention of 1929—also known as the Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, Geneva 27 July 1929—which was the version of the Geneva Convention that covered the treatment of prisoners of war during World War II. Nevertheless, Japan ratified the

Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions were am ...

which contained provisions regarding prisoners of war and an Imperial Proclamation in 1894 stated that Japanese soldiers should make every effort to win the war without violating international laws. According to Japanese historian

Yuki Tanaka, Japanese forces during the First Sino-Japanese War released 1,790 Chinese prisoners without harm, once they signed an agreement not to take up arms against Japan if they were released.

[Tanaka ''Hidden Horrors'' pp. 72–73] After the

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

of 1904–1905, all of the 79,367

Russian prisoners who were held by the Japanese were released and they were also paid for the labor which they performed for the Japanese, in accordance with the Hague Convention.

Similarly, the behavior of the Japanese military in

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

was at least as humane as that of other militaries which fought during the war, with some

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

prisoners of the Japanese finding life in Japan so agreeable that they stayed and settled in Japan after the war.

The events of the 1930s and 1940s

By the late 1930s, the rise of militarism in Japan created at least superficial similarities between the wider Japanese military culture and that of

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

's elite military personnel, such as those in the ''

Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscripts from both occup ...

''. Japan also had a military

secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic ...

force within the

IJA, known as the ''

Kenpeitai

The , also known as Kempeitai, was the military police arm of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1881 to 1945 that also served as a secret police force. In addition, in Japanese-occupied territories, the Kenpeitai arrested or killed those suspec ...

'', which resembled the Nazi ''

Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

'' in its role in annexed and occupied countries, but which had existed for nearly a decade before

Hitler's

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

own birth.

Perceived failure or insufficient devotion to the Emperor would attract punishment, frequently of the physical kind.

John Toland

John Toland (30 November 167011 March 1722) was an Irish rationalist philosopher and freethinker, and occasional satirist, who wrote numerous books and pamphlets on political philosophy and philosophy of religion, which are early expressions o ...

, '' The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945''. p. 301. Random House. New York. 1970 In the military, officers would assault and beat men under their command, who would pass the beating all the way down on to the lowest ranks. In

POW camps

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. ...

, this meant that prisoners received the worst beatings of all, partly in the belief that such punishments were merely the proper technique to deal with disobedience.

War crimes

The

Imperial Japanese Armed Forces

The Imperial Japanese Armed Forces (IJAF) were the combined military forces of the Japanese Empire. Formed during the Meiji Restoration in 1868,"One can date the 'restoration' of imperial rule from the edict of 3 January 1868." p. 334. they ...

during the 1930s and 1940s is often compared to the

Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

of

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

from 1933 to 1945 because of the sheer scale of destruction and suffering that both of them caused. Much of the controversy regarding Japan's role in World War II revolves around the death rates of prisoners of war and civilians under Japanese occupation. Historian

Sterling Seagrave

Sterling Seagrave (April 15, 1937 – May 1, 2017) was an American historian. He was the author of numerous books which address unofficial and clandestine aspects of the 20th-century political history of countries in the Far East.

Personal life

Bo ...

has written that:

According to the findings of the Tokyo Tribunal, the death rate among prisoners of war from Asian countries held by Japan was 27.1%. The death rate of Chinese prisoners of war were much higher because—under a directive ratified on 5 August 1937, by Emperor

Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

—the constraints of international law on treatment of those prisoners was removed. Only 56 Chinese prisoners of war were released after the

surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Na ...

. After 20 March 1943, officers of the Imperial Japanese Navy ordered and encouraged the Navy to execute all prisoners taken at sea.

On May 14, 1943, a Japanese submarine torpedoed the Australian hospital ship,

AHS ''Centaur'', sinking it within three minutes and killing 268 of the 332 people on board. The ''Centaur'' was painted with red crosses and well lit. The submarine knowingly sank a hospital ship.

According to British historian

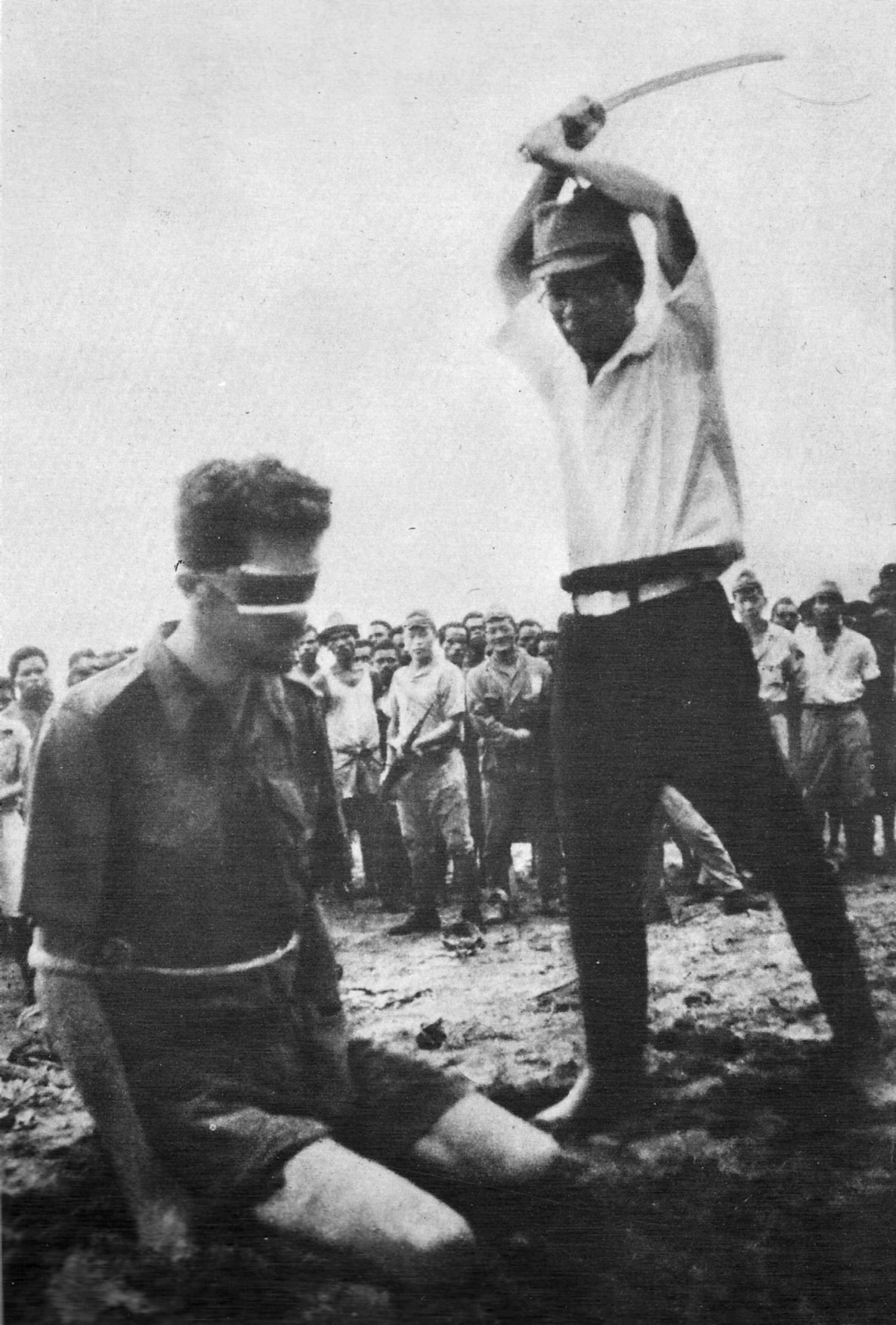

Mark Felton, "officers of the Imperial Japanese Navy ordered the deliberately sadistic murders of more than 20,000 Allied seamen and countless civilians in cold-blooded defiance of the Geneva Convention." At least 12,500 British sailors and 7,500 Australians were murdered. The Japanese Navy sank Allied merchant and Red Cross vessels, then murdered the survivors floating in the sea or in lifeboats. During Naval landing parties, the Japanese Navy rounded up, raped, then massacred civilians. Some of the victims were fed to sharks, others were killed by sledge-hammer, bayonet, crucifixion, drowning, hanging and beheading.

Attacks on parachutists and downed airmen

As the

Battle of Shanghai

The Battle of Shanghai () was the first of the twenty-two major engagements fought between the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Republic of China (ROC) and the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) of the Empire of Japan at the beginning of the ...

and

Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), Postal Map Romanization, alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and t ...

signaled the beginning of World War II in Asia, fierce air battles raged across China between the airmen of the

Chinese Air Force

The People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF; ), also known as the Chinese Air Force (中国空军) or the People's Air Force (人民空军), is an aerial service branch of the People's Liberation Army, the regular armed forces of the Peo ...

and the

Imperial Japanese Navy Air Force and

Imperial Japanese Army Air Force

The Imperial Japanese Army Air Service (IJAAS) or Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF; ja, 大日本帝國陸軍航空部隊, Dainippon Teikoku Rikugun Kōkūbutai, lit=Greater Japan Empire Army Air Corps) was the aviation force of the Im ...

, and the Japanese soon gained notoriety for

strafing

Strafing is the military practice of attacking ground targets from low-flying aircraft using aircraft-mounted automatic weapons.

Less commonly, the term is used by extension to describe high-speed firing runs by any land or naval craft such ...

downed airmen trying to descend to safety in their parachutes; the very first recorded act of Japanese fighter pilots strafing downed airmen occurred on 19 September 1937, when Chinese Air Force pilot Lt. Liu Lanqing (劉蘭清) of the

17th Pursuit Squadron, 3rd Pursuit Group flying

P-26 Model 281 fighters, was part of an intercept mission against a force of 30 Japanese bombers and fighters attacking Nanjing. Lt. Liu bailed out in his parachute after his plane was shot up and disabled, and while hanging in his parachute during descent, was killed by the Japanese pilots taking turns strafing him; his flight leader, Capt.

John Huang Xinrui, tried shooting at those Japanese pilots shooting at the helpless Lt. Liu, but was shot up himself and had to bail out, waiting until the last possible moment to pull his parachute cord to avoid the cruelty of the Japanese pilots. As a result, Chinese and Russian volunteer pilots were all warned about opening their parachutes too early if bailing out of stricken aircraft.

But even after a safe parachute descent, the Japanese still went after downed airmen; on 18 July 1938,

Soviet volunteer pilot Valentin Dudonov was hit by an

A5M fighter piloted by

Nangō Mochifumi, after which Dudonov bailed out in his parachute and landed on a sand bank on

Poyang Lake

Poyang Lake (, Gan: Po-yong U), located in Jiujiang, is the largest freshwater lake in China.

The lake is fed by the Gan, Xin, and Xiu rivers, which connect to the Yangtze through a channel.

The area of Poyang Lake fluctuates dramatically ...

, only to be continuously strafed by another A5M. Dudonov, running in wild zig-zags and eventually hiding underwater in the lake, survived when the Japanese A5M finally departed. When the Americans joined the war in 1941, they too endured many harrowing and tragic war crimes, clarified by and prosecutable under the

protocols of the Geneva Convention.

Attacks on neutral powers

Article 1 of the

1907 Hague Convention ''III – The Opening of Hostilities'' prohibited the initiation of hostilities against neutral powers "without previous and explicit warning, in the form either of a reasoned

declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national government, ...

or of an

ultimatum with conditional declaration of war" and Article 2 further stated that "

e existence of a state of war must be notified to the neutral Powers without delay, and shall not take effect in regard to them until after the receipt of a notification, which may, however, be given by telegraph." Japanese diplomats intended to deliver the notice to the United States thirty minutes before the

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

occurred on 7 December 1941, but it was delivered to the

U.S. government an hour after the attack was over. Tokyo transmitted the 5,000-word notification (commonly called the "14-Part Message") in two blocks to the

Japanese Embassy in Washington, but transcribing the message took too long for the Japanese ambassador to deliver it in time.

The 14-Part Message was not moreover a declaration of war, but was instead about sending a message to U.S. officials that peace negotiations between Japan and the U.S. were likely to be terminated. Japanese officials were well aware that the 14-Part Message was not a proper declaration of war as required by the 1907 Hague Convention ''III – The Opening of Hostilities''. They decided not to issue a proper declaration of war anyway as they feared that doing so would expose their secret attack on Pearl Harbor to the Americans.

Some

historical negationists and

conspiracy theorists

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

charge that President

Franklin D. Roosevelt willingly allowed the attack to happen to create a pretext for war, but no credible evidence exists to support the claim. The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor,

Japan declared war on the U.S. and in response, the

U.S. declared war on Japan the same day.

Simultaneously with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 (Honolulu time), Japan

invaded the British colony of Malaya and

bombed Singapore, and began

land actions in Hong Kong, without a declaration of war or an ultimatum. Both the United States and United Kingdom were neutral when Japan attacked their territories without explicit warning of a state of war.

The U.S. officially classified all 3,649 military and civilian casualties and destruction of military property at Pearl Harbor as

non-combatant

Non-combatant is a term of art in the law of war and international humanitarian law to refer to civilians who are not taking a direct part in hostilities; persons, such as combat medics and military chaplains, who are members of the belligere ...

s as there was no state of war between the U.S. and Japan when the attack occurred.

Joseph B. Keenan

Joseph Berry Keenan (11 January 1888, in Pawtucket, Rhode Island – 8 December 1954, in Asheboro, North Carolina , the chief prosecutor in the Tokyo Trials, says that the attack on Pearl Harbor not only happened without a declaration of war but was also a "

treacherous and

deceitful act". In fact, Japan and the U.S. were still negotiating for a possible peace agreement which kept U.S. officials distracted up to the point that Japanese planes launched their attack on Pearl Harbor. Keenan explained the definition of a war of aggression and the criminality of the attack on Pearl Harbor:

Admiral

Isoroku Yamamoto

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet during World War II until he was killed.

Yamamoto held several important posts in the IJN, and undertook many of its changes and reor ...

, who planned the attack on Pearl Harbor, was fully aware that if Japan lost the war, he would be tried as a war criminal for that attack; as it turned out, he was killed by the

USAAF

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

in

Operation Vengeance

Operation Vengeance was the American military operation to kill Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto of the Imperial Japanese Navy on April 18, 1943, during the Solomon Islands campaign in the Pacific Theater of World War II. Yamamoto, commander of the Comb ...

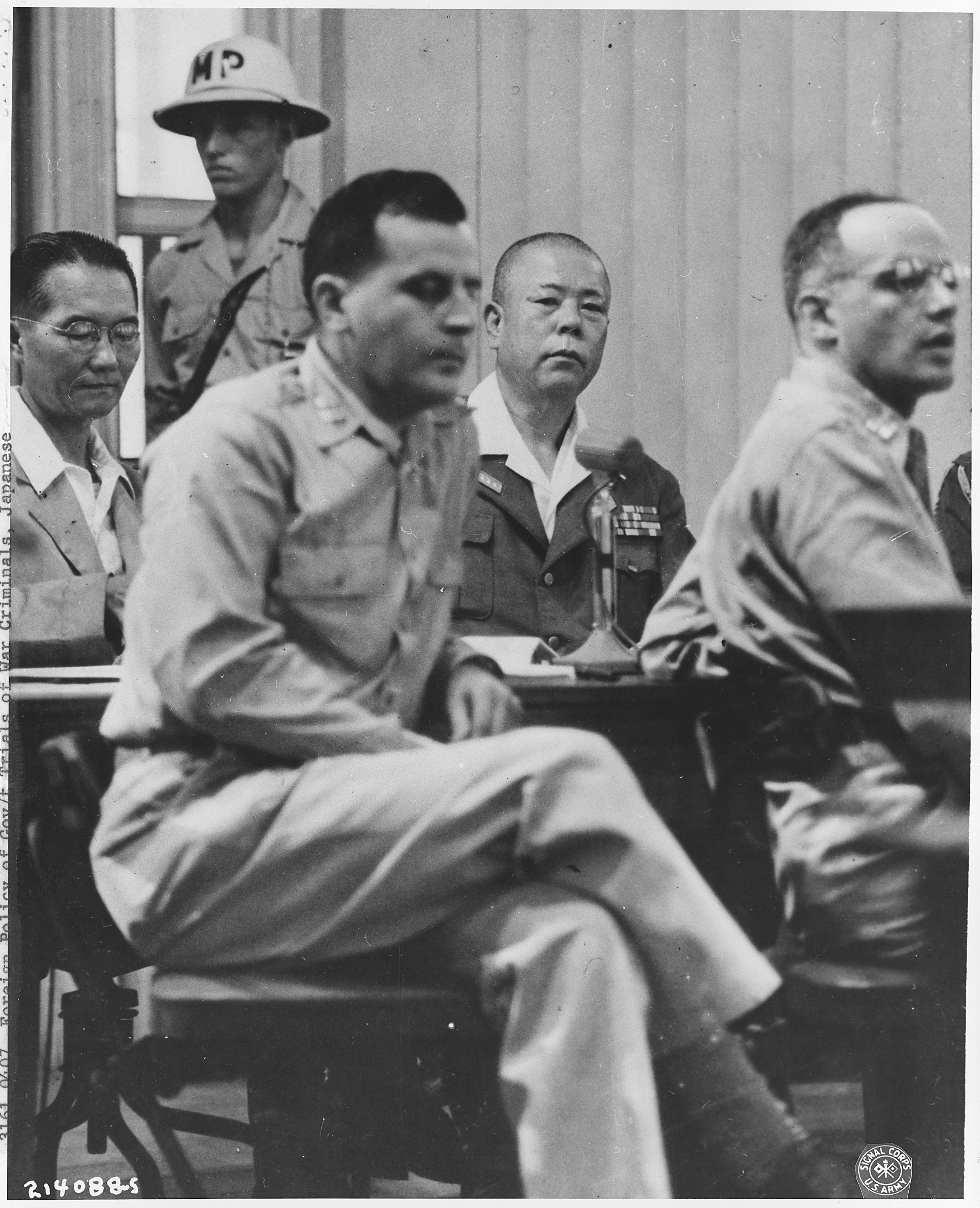

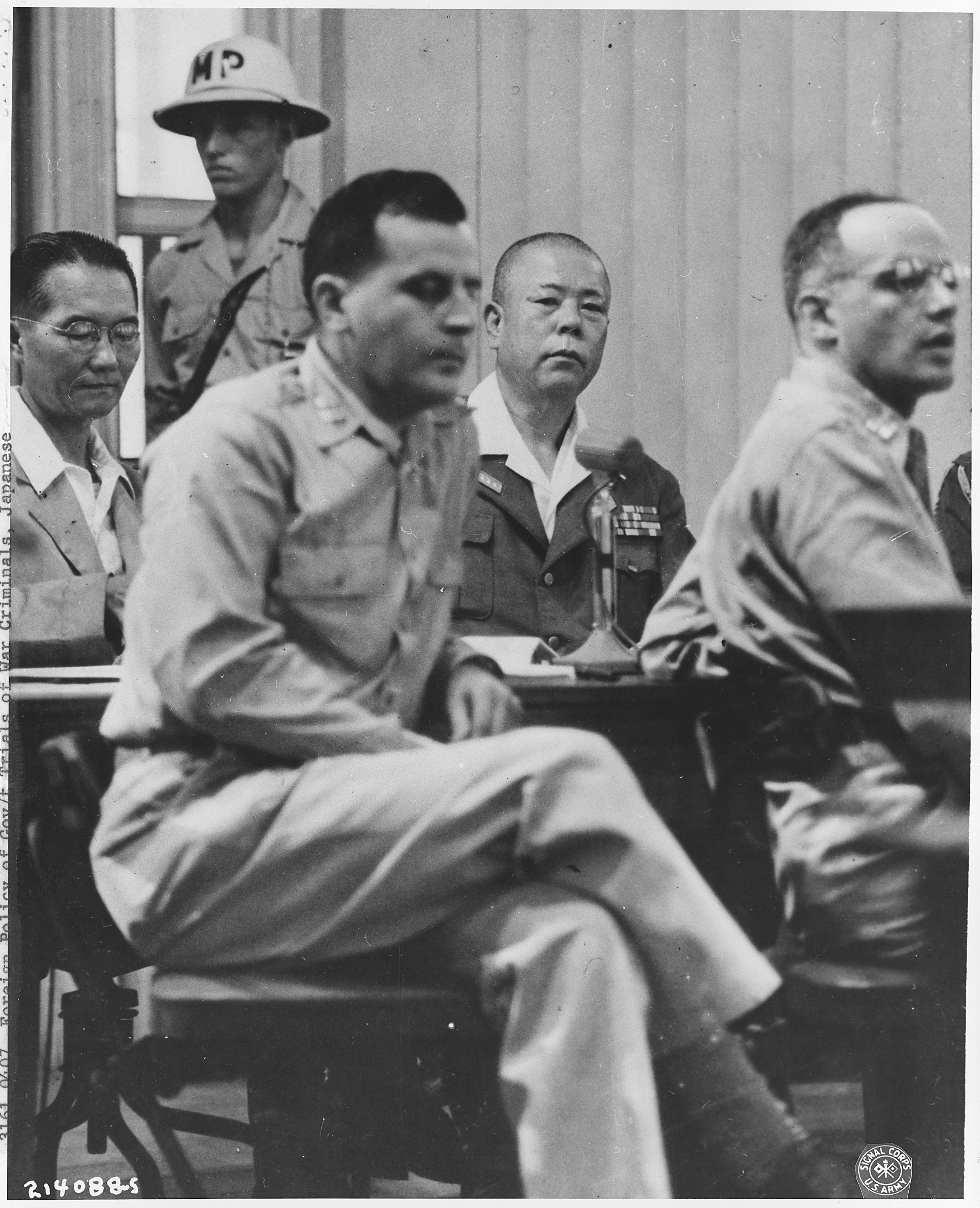

in 1943. At the Tokyo Trials, Prime Minister

Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

,

Shigenori Tōgō

(10 December 1882 – 23 July 1950), was Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Empire of Japan at both the start and the end of the Axis–Allied conflict during World War II. He also served as Minister of Colonial Affairs in 1941, and assume ...

, then

Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

,

Shigetarō Shimada

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II. He also served as Minister of the Navy. He was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Early life and education

A native of Tokyo, Shimada graduated from ...

, the

Minister of the Navy Minister of the Navy may refer to:

* Minister of the Navy (France)

* Minister of the Navy (Italy)

* Minister of the Navy (Japan)

* Minister of the Navy (Netherlands)

* Minister of the Navy (Spain)

* Minister of the Navy (Turkey)

* Minister of ...

, and

Osami Nagano

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy and one of the leaders of Japan's military during most of the Second World War. In April 1941, he became Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff. In this capacity, he served as the ...

,

Chief of Naval General Staff, were charged with

crimes against peace

A crime of aggression or crime against peace is the planning, initiation, or execution of a large-scale and serious act of aggression using state military force. The definition and scope of the crime is controversial. The Rome Statute contains an ...

(charges 1 to 36) and murder (charges 37 to 52) in connection with the attack on Pearl Harbor. Along with

war crimes and

crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

(charges 53 to 55), Tojo was among the seven Japanese leaders sentenced to death and executed by

hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

in 1948, Shigenori Tōgō received a 20-year sentence, Shimada received a

life sentence

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment for a crime under which convicted people are to remain in prison for the rest of their natural lives or indefinitely until pardoned, paroled, or otherwise commuted to a fixed term. Crimes ...

, and Nagano died of natural causes during the Trial in 1947.

Over the years, many

Japanese nationalists

is a form of nationalism that asserts the belief that the Japanese are a monolithic nation with a single immutable culture, and promotes the cultural unity of the Japanese. Over the last two centuries, it has encompassed a broad range of ideas a ...

argued that the attack on Pearl Harbor was justified as an act of self-defense in response to the

oil embargo An oil embargo is an economic situation wherein entities engage in an embargo to limit the transport of petroleum to or from an area, in order to exact some desired outcome. One commentator states, " oil embargo is not a common commercial practice; ...

imposed by the United States. Most historians and scholars agree that the oil embargo cannot be used as justification for using military force against a foreign nation imposing the embargo because there is a clear distinction between a perception of something being essential to the welfare of the nation-state and a threat sufficiently serious to warrant an act of force in response, which Japan had failed to consider. Japanese scholar and diplomat Takeo Iguchi states that it is "

rd to say from the perspective of international law that exercising the right of self-defense against economic pressures is considered valid." While Japan felt that its dreams of further expansion would be brought to a halt by the American embargo, this "need" cannot be considered

proportional with the destruction suffered by the

U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, intended by Japanese military planners to be as devastating as possible.

Mass killings

The estimated number of people killed by Japanese troops vary.

R. J. Rummel

Rudolph Joseph Rummel (October 21, 1932 – March 2, 2014) was an American political scientist and professor at the Indiana University, Yale University, and University of Hawaiʻi. He spent his career studying data on collective violence and war w ...

, a professor of political science at the

University of Hawaii

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, th ...

, estimates that between 1937 and 1945, the Japanese military murdered from nearly three to over ten million people, most likely six million Chinese, Indians,

Koreans

Koreans ( South Korean: , , North Korean: , ; see names of Korea) are an East Asian ethnic group native to the Korean Peninsula.

Koreans mainly live in the two Korean nation states: North Korea and South Korea (collectively and simply r ...

,

Malaysians

Malaysians are nationals and citizens who are identified with the country of Malaysia. Although citizens make up the majority of Malaysians, non-citizen residents and overseas Malaysians may also claim a Malaysian identity.

The country is h ...

,

Indonesians

Indonesians ( Indonesian: ''orang Indonesia'') are citizens or people originally from Indonesia, regardless of their ethnic or religious background. There are more than 1,300 ethnicities in Indonesia, making it a multicultural archipelagic co ...

,

Filipinos

Filipinos ( tl, Mga Pilipino) are the people who are citizens of or native to the Philippines. The majority of Filipinos today come from various Austronesian ethnolinguistic groups, all typically speaking either Filipino, English and/or other ...

and

Indochinese

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

, among others, including European, American and Australian prisoners of war. According to Rummel, "This

democide

Democide is a term coined by American political scientist Rudolph Rummel to describe "the intentional killing of an unarmed or disarmed person by government agents acting in their authoritative capacity and pursuant to government policy or hig ...

.e., death by governmentwas due to a morally bankrupt political and military strategy, military expediency and custom, and national culture."

[ According to Rummel, in China alone, from 1937 to 1945, approximately 3.9 million Chinese were killed, mostly civilians, as a direct result of the Japanese operations and a total of 10.2 million Chinese were killed in the course of the war. According to the British historian ]M. R. D. Foot

Michael Richard Daniell Foot, (14 December 1919 – 18 February 2012) was a British political and military historian, and former British Army intelligence officer with the Special Operations Executive during the Second World War.

Biography

The ...

, civilian deaths were between 10 million and 20 million. Some historians claim that up to 30 million people were killed, most of them civilians.The Japanese murdered 30 million civilians while "liberating" what it called the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the Empire of Japan and propagated to Asian populations which were occupied by it from 1931 to 1945, and which officially aimed at creating a self-sufficient bloc of Asian peo ...

from colonial rule. About 23 million of these were ethnic Chinese. It is a crime that in sheer numbers is far greater than the Nazi Holocaust. In Germany, Holocaust denial is a crime. In Japan, it is government policy. But the evidence against the navy – precious little of which you will find in Japan itself – is damning.

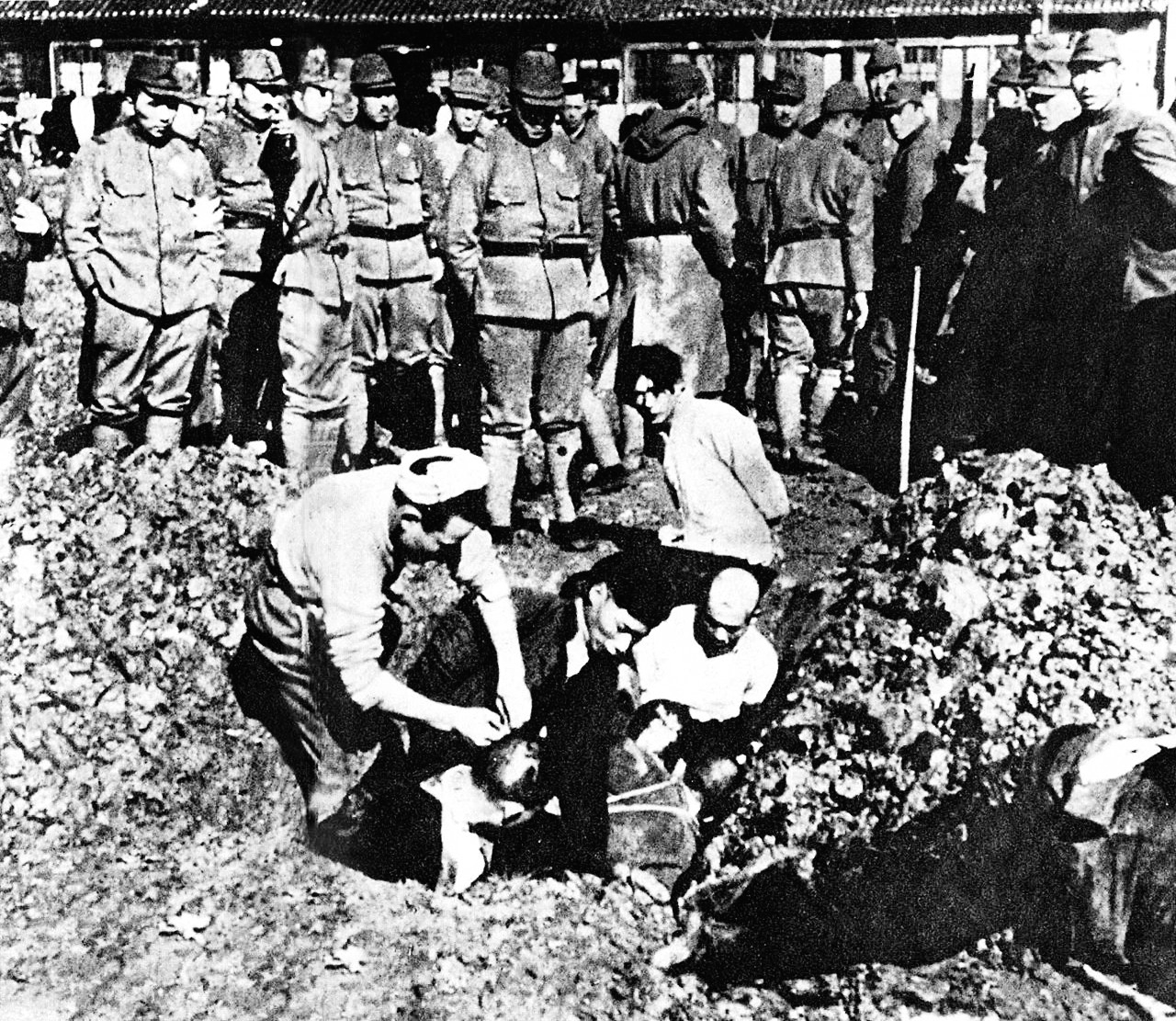

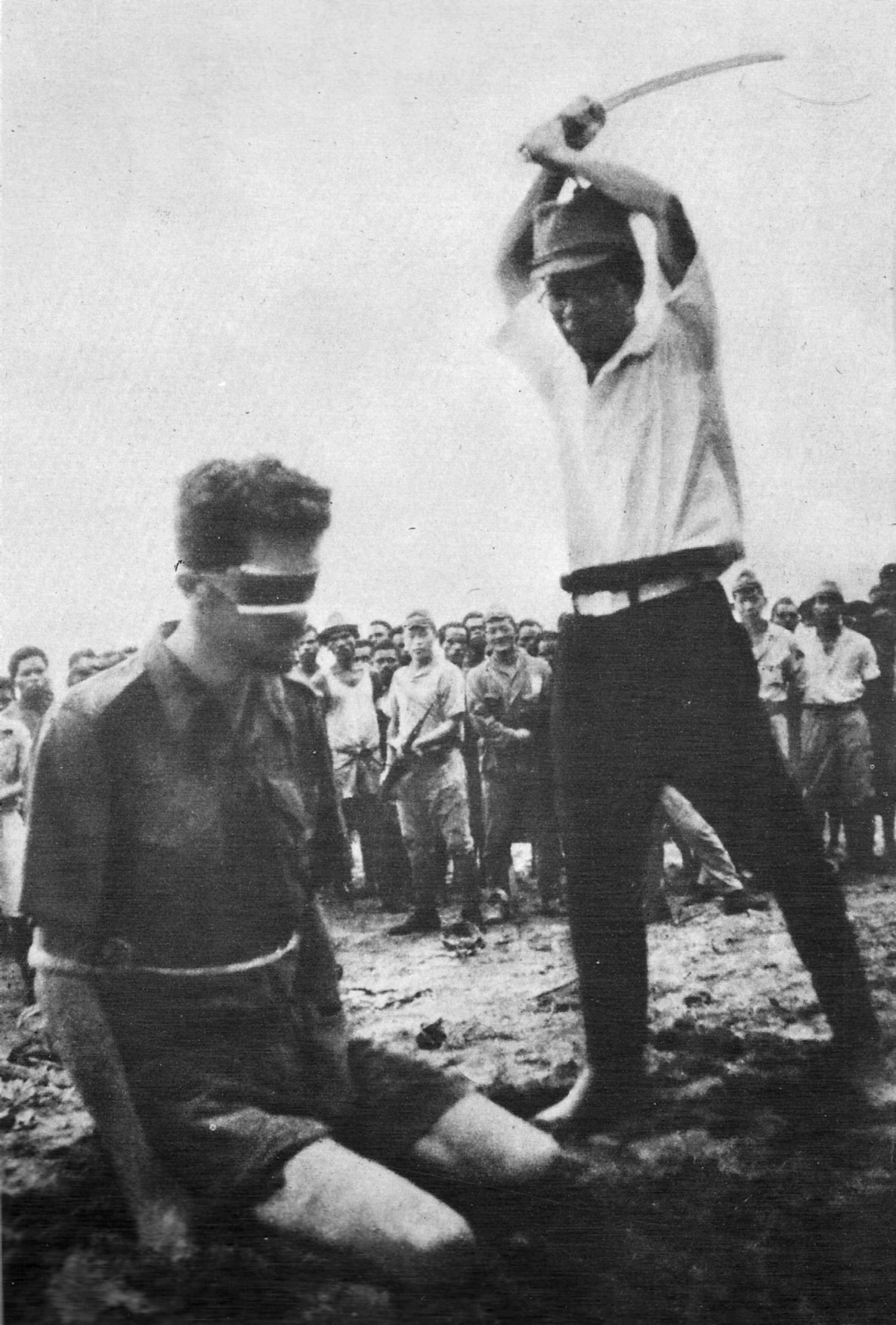

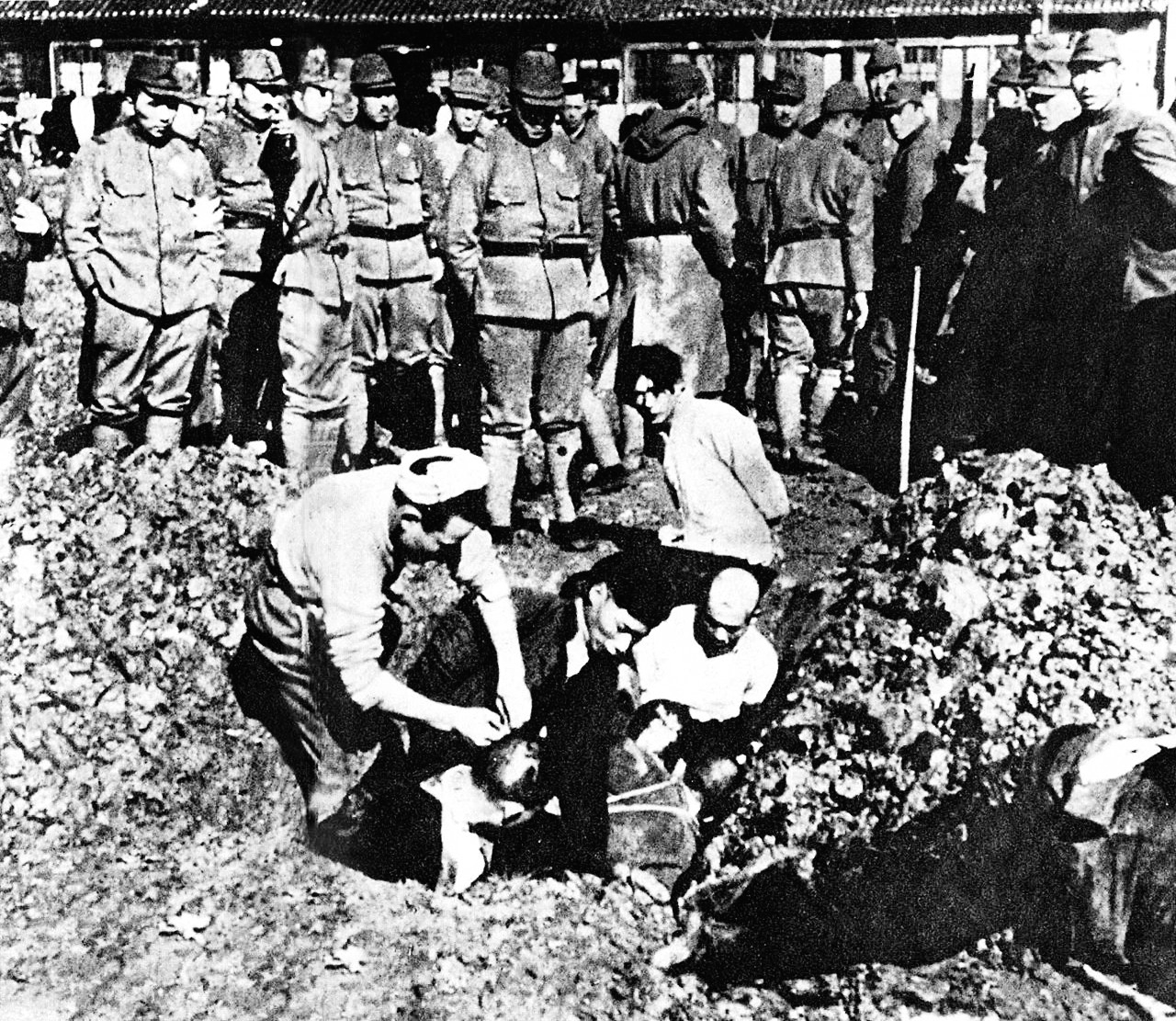

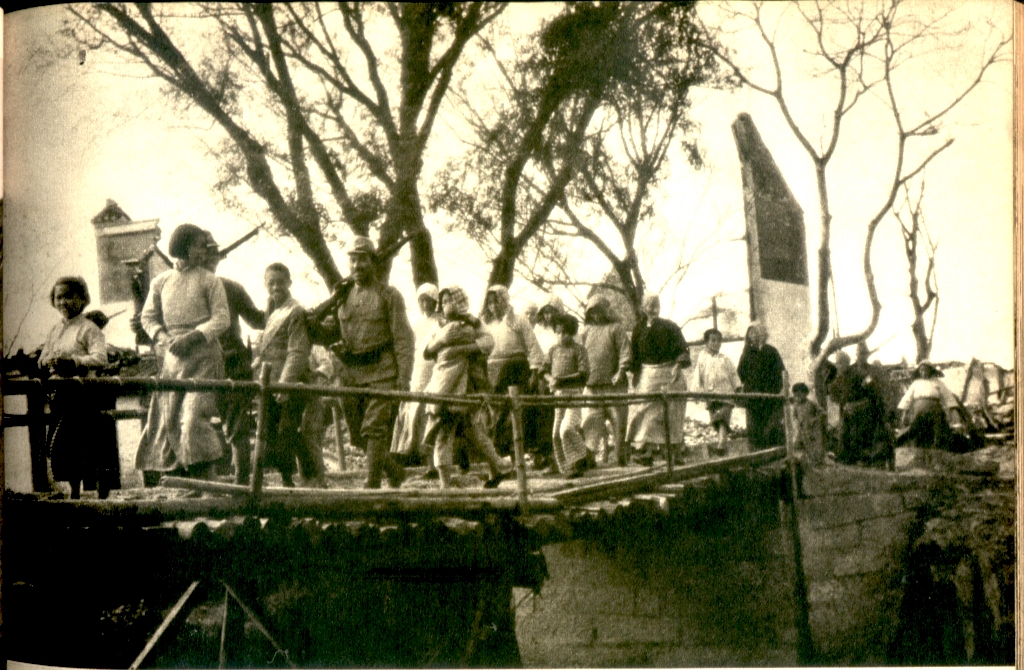

The most infamous incident during this period was the Nanking Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the ...

of 1937–38, when, according to the findings of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for crimes against peace, conv ...

, the Japanese Army massacred as many as 260,000 civilians and prisoners of war, though some have placed the figure as high as 350,000. The Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders has the death figure of 300,000 inscribed on its entrance.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific T ...

, the Japanese followed what has been called a "killing policy", including killings committed against minorities such as Hui Muslims in China. According to Wan Lei, "In a Hui clustered village in Gaocheng county

Gaocheng () is one of eight districts of the prefecture-level city of Shijiazhuang, the capital of Hebei Province, North China, on the upper reaches of the Hutuo River (). The city has a total area of and in 2010 had a population of 743,000.< ...

of Hebei

Hebei or , (; alternately Hopeh) is a northern province of China. Hebei is China's sixth most populous province, with over 75 million people. Shijiazhuang is the capital city. The province is 96% Han Chinese, 3% Manchu, 0.8% Hui, and ...

, the Japanese captured twenty Hui men among whom they only set two younger men free through "redemption", and buried alive the other eighteen Hui men. In Mengcun

Mengcun (; Xiao'erjing: ) is a Hui autonomous county of southeastern Hebei province, China, under the administration of Cangzhou

Cangzhou () is a prefecture-level city in eastern Hebei province, People's Republic of China. At the 2020 censu ...

village of Hebei, the Japanese killed more than 1,300 Hui people within three years of their occupation of that area." Mosques were also desecrated and destroyed by the Japanese, and Hui cemeteries were also destroyed. After the Rape of Nanking

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the Ba ...

, mosques in Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), Postal Map Romanization, alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and t ...

were found filled with dead bodies. Many Hui Muslims in the Second Sino-Japanese War fought against the Japanese military.

In addition, The Hui Muslim county of Dachang was subjected to massacres by the Japanese military.

One of the most infamous incidents during this period was the Parit Sulong massacre

On 22 January 1942, the Parit Sulong Massacre in Johor, Malaya (now Malaysia) was committed against Allied soldiers by members of the Imperial Guards Division of the Imperial Japanese Army. A few days earlier, the Allied troops had ambushed the ...

in Japanese-occupied Malaya, when, according to the findings of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for crimes against peace, conv ...

, the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emper ...

massacred approximately five hundred prisoners of war, although higher estimates exist. A similar crime committed was the Changjiao massacre in China. Back in Southeast Asia, the Laha massacre Laha can refer to:

Laha people, an ethnic group in Vietnam

Places

* Laha, Seram, Indonesia

* Laha, Heilongjiang, a town in Nehe City, Heilongjiang, China

* ''Laha airfield'' near Laha Village, on Ambon Island, Indonesia

Languages

* Laha ...

resulted in the deaths of prisoners of war on Japanese-occupied Indonesia's Ambon Island, and in Japanese-occupied Singapore

, officially , was the name for Singapore when it was occupied and ruled by the Empire of Japan, following the fall and surrender of British military forces on 15 February 1942 during World War II.

Japanese military forces occupied it afte ...

's Alexandra Hospital massacre

The Fall of Singapore, also known as the Battle of Singapore,; ta, சிங்கப்பூரின் வீழ்ச்சி; ja, シンガポールの戦い took place in the South–East Asian theatre of the Pacific War. The Empire o ...

, hundreds of wounded Allied soldiers, innocent citizens and medical staff were murdered by Japanese soldiers.

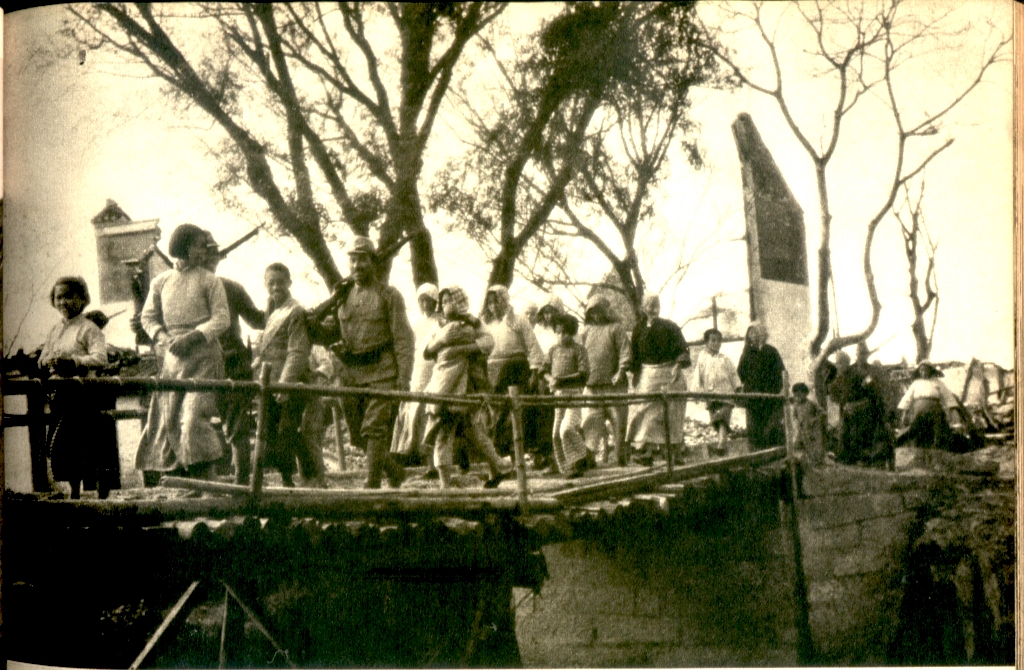

In Southeast Asia, the Manila massacre

The Manila massacre ( fil, Pagpatay sa Maynila or ''Masaker sa Maynila''), also called the Rape of Manila ( fil, Paggahasa ng Maynila), involved atrocities committed against Filipino civilians in the City of Manila, the capital of the Phili ...

of February 1945 resulted in the death of 100,000 civilians in the Japanese-occupied Philippines. It is estimated that at least one out of every 20 Filipinos died at the hands of the Japanese during the occupation. In Singapore during February and March 1942, the Sook Ching massacre was a systematic extermination

Extermination or exterminate may refer to:

* Pest control, elimination of insects or vermin

* Genocide, extermination—in whole or in part—of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group

* Homicide or murder in general

* "Exterminate!", the ...

of "anti-Japanese" elements among the Chinese population; however, Japanese soldiers did not try to identify who was "anti-Japanese." As a result, the Japanese soldiers engaged in indiscriminate killing. Former Prime Minister of Singapore

The prime minister of Singapore is the head of government of the Republic of Singapore. The president appoints the prime minister, a Member of Parliament (MP) who in their opinion, is most likely to command the confidence of the majority o ...

Lee Kuan Yew

Lee Kuan Yew (16 September 1923 – 23 March 2015), born Harry Lee Kuan Yew, often referred to by his initials LKY, was a Singaporean lawyer and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Singapore between 1959 and 1990, and Secretary-General o ...

, who was almost a victim of the Sook Ching Massacre, has stated that there were between 50,000 and 90,000 casualties, while according to Major General Kawamura Saburo, there were 5,000 casualties in total. According to Lieutenant Colonel Hishakari Takafumi, a newspaper correspondent at the time, the plan was to ultimately kill about 50,000 Chinese, and 25,000 had already been murdered when the order was received to scale down the operation.

There were other massacres of civilians, e.g. the Kalagon massacre

On 7 July 1945, the Kalagon massacre was committed against inhabitants of Kalagon, Burma (present-day Myanmar), by members of the 3rd Battalion, 215th Regiment and the OC Moulmein Kempeitai of the Imperial Japanese Army. These units had been ord ...

. In wartime Southeast Asia, the Overseas Chinese

Overseas Chinese () refers to people of Chinese birth or ethnicity who reside outside Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. As of 2011, there were over 40.3 million overseas Chinese.

Terminology

() or ''Hoan-kheh'' () in Hokkien, ref ...

and European diaspora

European emigration is the successive emigration waves from the European continent to other continents. The origins of the various European diasporas can be traced to the people who left the European nation states or stateless ethnic communities ...

were special targets of Japanese abuse; in the former case, motivated by Sinophobia vis-à-vis the historic expanse and influence of Chinese culture

Chinese culture () is one of the world's oldest cultures, originating thousands of years ago. The culture prevails across a large geographical region in East Asia and is extremely diverse and varying, with customs and traditions varying grea ...

that did not exist with the Southeast Asian indigenes, and the latter, motivated by a racist

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

Pan-Asianism

Satellite photograph of Asia in orthographic projection.

Pan-Asianism (''also known as Asianism or Greater Asianism'') is an ideology aimed at creating a political and economic unity among Asian peoples. Various theories and movements of Pan-Asi ...

and a desire to show former colonial subjects the impotence of their Western masters. The Japanese executed all the Malay Sultans on Kalimantan and wiped out the Malay elite in the Pontianak incidents. In the Jesselton Revolt, the Japanese slaughtered thousands of native civilians during the Japanese occupation of British Borneo

Before the outbreak of World War II in the Pacific, the island of Borneo was divided into five territories. Four of the territories were in the north and under British control – Sarawak, Brunei, Labuan, an island, and British North Borneo; ...

and nearly wiped out the entire Suluk Muslim population of the coastal islands. During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines

The Japanese occupation of the Philippines ( Filipino: ''Pananakop ng mga Japones sa Filipinas''; ja, 日本のフィリピン占領, Nihon no Firipin Senryō) occurred between 1942 and 1945, when Imperial Japan occupied the Commonwealth of t ...

, when a Moro Muslim juramentado

Juramentado, in Philippine history, refers to a male Moro swordsman (from the Tausug tribe of Sulu) who attacked and killed targeted occupying and invading police and soldiers, expecting to be killed himself, the martyrdom undertaken as a form of ...

swordsman

Swordsmanship or sword fighting refers to the skills and techniques used in combat and training with any type of sword. The term is modern, and as such was mainly used to refer to smallsword fencing, but by extension it can also be applied to an ...

launched a suicide attack against the Japanese, the Japanese would massacre the man's entire family or village.

Historian Mitsuyoshi Himeta reports that a "Three Alls Policy

The Three Alls Policy (, ja, 三光作戦 Sankō Sakusen) was a Japanese scorched earth policy adopted in China during World War II, the three "alls" being . This policy was designed as retaliation against the Chinese for the Communist-led Hundr ...

" (''Sankō Sakusen'') was implemented in China from 1942 to 1945 and was in itself responsible for the deaths of "more than 2.7 million" Chinese civilians. This scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, commun ...

strategy, sanctioned by Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

himself, directed Japanese forces to "Kill All, Burn All, and Loot All", which caused many massacres such as the Panjiayu massacre, where 1,230 Chinese people were killed, Additionally, captured Allied servicemen and civilians were massacred in various incidents, including the following:

* Alexandra Hospital massacre

The Fall of Singapore, also known as the Battle of Singapore,; ta, சிங்கப்பூரின் வீழ்ச்சி; ja, シンガポールの戦い took place in the South–East Asian theatre of the Pacific War. The Empire o ...

* Laha massacre Laha can refer to:

Laha people, an ethnic group in Vietnam

Places

* Laha, Seram, Indonesia

* Laha, Heilongjiang, a town in Nehe City, Heilongjiang, China

* ''Laha airfield'' near Laha Village, on Ambon Island, Indonesia

Languages

* Laha ...

Bangka Island massacre

The Bangka Island massacre (also spelled Banka Island massacre) was the killing of unarmed Australian nurses and wounded Allied soldiers on Bangka Island, east of Sumatra in the Indonesian archipelago on 16 February 1942. Shortly after the ou ...

Parit Sulong Massacre

On 22 January 1942, the Parit Sulong Massacre in Johor, Malaya (now Malaysia) was committed against Allied soldiers by members of the Imperial Guards Division of the Imperial Japanese Army. A few days earlier, the Allied troops had ambushed the ...

* Palawan massacre

* SS ''Behar''

* SS ''Tjisalak'' massacre perpetrated by Japanese submarine ''I-8''

* Wake Island massacre

* Tinta Massacre

* Bataan Death March

The Bataan Death March ( Filipino: ''Martsa ng Kamatayan sa Bataan''; Spanish: ''Marcha de la muerte de Bataán'' ; Kapampangan: ''Martsa ning Kematayan quing Bataan''; Japanese: バターン死の行進, Hepburn: ''Batān Shi no Kōshin'') ...

* Sandakan Death Marches

* ''Shin'yō Maru'' Incident

* Sulug Island massacre

* Pontianak incidents

* Manila massacre

The Manila massacre ( fil, Pagpatay sa Maynila or ''Masaker sa Maynila''), also called the Rape of Manila ( fil, Paggahasa ng Maynila), involved atrocities committed against Filipino civilians in the City of Manila, the capital of the Phili ...

(concurrent with the Battle of Manila)

* Balikpapan massacre

* Rawagede massacre

The Rawagede massacre ( nl, Bloedbad van Rawagede, ind, Pembantaian Rawagede), was committed by the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army on 9 December 1947 in the village of Rawagede (now Balongsari in Rawamerta district, Karawang Regency, Wes ...

* Dutch East Indies massacres

Naval Base Borneo and Naval Base Dutch East Indies was a number of United States Navy Advance Bases and bases of the Australian Armed Forces in Borneo and Dutch East Indies during World War II. At the start of the war, the island was divided i ...

Human experimentation and biological warfare

Special Japanese military units conducted experiments on civilians and POWs in China. One of the most infamous was

Special Japanese military units conducted experiments on civilians and POWs in China. One of the most infamous was Unit 731

, short for Manshu Detachment 731 and also known as the Kamo Detachment and Ishii Unit, was a covert Biological warfare, biological and chemical warfare research and development unit of the Imperial Japanese Army that engaged in unethical h ...

under Shirō Ishii

Surgeon General was a Japanese microbiologist and army medical officer who served as the director of Unit 731, a biological warfare unit of the Imperial Japanese Army.

Ishii led the development and application of biological weapons at Unit 73 ...

. Unit 731 was established by order of Hirohito himself. Victims were subjected to experiments including but not limited to vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for experiment ...

, amputations without anesthesia, testing of biological weapons

A biological agent (also called bio-agent, biological threat agent, biological warfare agent, biological weapon, or bioweapon) is a bacterium, virus, protozoan, parasite, fungus, or toxin that can be used purposefully as a weapon in bioterrorism ...

, horse blood transfusions, and injection of animal blood into their corpses. Anesthesia was not used because it was believed that anesthetics would adversely affect the results of the experiments.

According to one estimate, the experiments carried out by Unit 731 alone caused 3,000 deaths. Furthermore, according to the 2002 ''International Symposium on the Crimes of Bacteriological Warfare'', the number of people killed by the Imperial Japanese Army germ warfare and human experiments is around 580,000. Top officers of Unit 731 were not prosecuted for war crimes after the war, in exchange for turning over the results of their research to the Allies. They were also reportedly given responsible positions in Japan's pharmaceutical industry, medical schools and health ministry.

One case of human experimentation occurred in Japan itself. At least

nine of 11 members of Lt.Marvin Watkins' 29th Bomb Group crew (of the 6th Bomb Squadron) survived the crash of their

One case of human experimentation occurred in Japan itself. At least

nine of 11 members of Lt.Marvin Watkins' 29th Bomb Group crew (of the 6th Bomb Squadron) survived the crash of their U.S. Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War ...

B-29

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fl ...

bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped from an air ...

on Kyūshū

is the third-largest island of Japan's five main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands ( i.e. excluding Okinawa). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regional name referred to Kyushu and its surround ...

, on 5 May 1945. The bomber's commander was separated from his crew and sent to Tokyo for interrogation, while the other survivors were taken to the anatomy department of Kyushu University

, abbreviated to , is a Japanese national university located in Fukuoka, on the island of Kyushu.

It was the 4th Imperial University in Japan, ranked as 4th in 2020 Times Higher Education Japan University Rankings, one of the top 10 Design ...

, at Fukuoka

is the sixth-largest city in Japan, the second-largest port city after Yokohama, and the capital city of Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan. The city is built along the shores of Hakata Bay, and has been a center of international commerce since anc ...

, where they were subjected to vivisection or killed.

In China, the Japanese waged ruthless biological warfare against Chinese civilians and soldiers. Japanese aviators sprayed fleas carrying plague germs over metropolitan areas, creating bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium ('' Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as wel ...

epidemics.cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

, dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

, typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several d ...

, anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The s ...

and paratyphoid, to contaminate rivers, wells, reservoirs and houses; mixed food with deadly bacteria to infect hungry Chinese civilians; and even passed out chocolate filled with anthrax bacteria to the local children.

During the final months of World War II, Japan had planned to use plague as a biological weapon against U.S. civilians in San Diego, California

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United Stat ...

, during Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night

Operation PX, also known as Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night, was a planned Japanese military attack on civilians in the United States using biological weapons, devised during World War II. The proposal was for Imperial Japanese Navy submar ...

, hoping that the plague would spread terror to the American population, and thereby dissuade America from attacking Japan. The plan was set to launch at night on 22 September 1945, but Japan surrendered five weeks earlier.

On 11 March 1948, 30 people, including several doctors and one female nurse, were brought to trial by the Allied war crimes tribunal. Charges of cannibalism were dropped, but 23 people were found guilty of vivisection or wrongful removal of body parts. Five were sentenced to death, four to life imprisonment, and the rest to shorter terms. In 1950, the military governor of Japan, General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

, commuted all of the death sentences and significantly reduced most of the prison terms. All of those convicted in relation to the university vivisection were free after 1958.

In 2006, former IJN medical officer Akira Makino (November 1922 – May 2007) was a former medic in the Imperial Japanese Navy who, in 2006, became the first Japanese ex-soldier to admit to the experiments conducted on human beings in the Philippines during World War II.

Early life

Makin ...