James Schlesinger on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Rodney Schlesinger (February 15, 1929 – March 27, 2014) was an American

Shortly after assuming office, Schlesinger outlined the basic objectives that would guide his administration: maintain a "strong defense establishment"; "assure the military balance so necessary to deterrence and a more enduring peace"; obtain for members of the military "the respect, dignity and support that are their due"; assume "an . . . obligation to use our citizens' resources wisely"; and "become increasingly competitive with potential adversaries.... must not be forced out of the market on land, at sea, or in the air.

Shortly after assuming office, Schlesinger outlined the basic objectives that would guide his administration: maintain a "strong defense establishment"; "assure the military balance so necessary to deterrence and a more enduring peace"; obtain for members of the military "the respect, dignity and support that are their due"; assume "an . . . obligation to use our citizens' resources wisely"; and "become increasingly competitive with potential adversaries.... must not be forced out of the market on land, at sea, or in the air.

The last phase of the

The last phase of the

Schlesinger's insistence on higher defense budgets, his disagreements within the administration and with Congress on this issue, and his differences with Secretary of State Kissinger all contributed to his dismissal by President Ford in November 1975. Schlesinger's legacy included the development of the close-air support aircraft the

Schlesinger's insistence on higher defense budgets, his disagreements within the administration and with Congress on this issue, and his differences with Secretary of State Kissinger all contributed to his dismissal by President Ford in November 1975. Schlesinger's legacy included the development of the close-air support aircraft the

After leaving the Pentagon, Schlesinger wrote and spoke forcefully about national security issues, especially the Soviet threat and the need for the United States to maintain adequate defenses. When

After leaving the Pentagon, Schlesinger wrote and spoke forcefully about national security issues, especially the Soviet threat and the need for the United States to maintain adequate defenses. When

''

After leaving the Energy Department, Schlesinger resumed his writing and speaking career, including the 1994 lecture at the Waldo Family Lecture on International Relations at

After leaving the Energy Department, Schlesinger resumed his writing and speaking career, including the 1994 lecture at the Waldo Family Lecture on International Relations at

On June 5, 2008, Defense Secretary Robert Gates appointed Schlesinger to head a task force to ensure the "highest levels" of control over nuclear weapons. The purpose of the review was to prevent a repeat of recent incidents where control was lost over components of nuclear weapons, and even over nuclear weapons themselves. Schlesinger was chairman of the Board of Trustees of MITRE, The MITRE Corporation, having served on it from 1985 until his death in 2014; on the advisory board of ''

Annotated Bibliography for James R. Schlesinger from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

*Chris Mooney, ''

"Stop Him Before He Writes Again: Will someone please make James Schlesinger disclose his energy-industry ties next time he writes an anti-global warming op-ed?"

a 17 September 2007 interview

MITRE BiographyMITRE mourns the death of its chairman

* * , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Schlesinger, James R. 1929 births 2014 deaths 20th-century American politicians Economists from New York (state) American Lutherans American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent American people of Austrian-Jewish descent Jewish American members of the Cabinet of the United States Carter administration cabinet members Chairmen of the United States Atomic Energy Commission Converts to Lutheranism from Judaism Directors of the Central Intelligence Agency English-only movement Ford administration cabinet members Harvard University alumni Horace Mann School alumni Mitre Corporation people New York (state) Republicans Nixon administration cabinet members Nixon administration personnel involved in the Watergate scandal Scientists from New York City United States Secretaries of Defense United States Secretaries of Energy University of Virginia faculty Foreign Policy Research Institute Writers from New York City

economist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social sciences, social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this ...

and public servant

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

who was best known for serving as Secretary of Defense

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in so ...

from 1973 to 1975 under Presidents Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

and Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

. Prior to becoming Secretary of Defense, he served as Chair of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) from 1971 to 1973, and as CIA Director

The director of the Central Intelligence Agency (D/CIA) is a statutory office () that functions as the head of the Central Intelligence Agency, which in turn is a part of the United States Intelligence Community.

Beginning February 2017, the D ...

for a few months in 1973. He became America's first Secretary of Energy

The United States secretary of energy is the head of the United States Department of Energy, a member of the Cabinet of the United States, and fifteenth in the presidential line of succession. The position was created on October 1, 1977, when Pr ...

under Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

in 1977, serving until 1979.

While Secretary of Defense, he opposed amnesty for draft resisters and pressed for development of more sophisticated nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

systems. Additionally, his support for the A-10

The Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II is a single-seat, twin-turbofan, straight-wing, subsonic attack aircraft developed by Fairchild Republic for the United States Air Force (USAF). In service since 1976, it is named for the Republic ...

and the lightweight fighter program (later the F-16

The General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon is a single-engine multirole fighter aircraft originally developed by General Dynamics for the United States Air Force (USAF). Designed as an air superiority day fighter, it evolved into a successf ...

) helped ensure that they were carried to completion.

Early life and career

James Rodney Schlesinger was born inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, the son of Jewish parents, Rhea Lillian (née Rogen) and Julius Schlesinger. His mother was a Lithuanian emigrant from what was then part of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

and his father's family was from Austria. He converted to Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

in his early twenties. Schlesinger was educated at the Horace Mann School

, motto_translation = Great is the truth and it prevails

, address = 231 West 246th Street

, city = The Bronx

, state = New York

, zipcode = 10471

, countr ...

and Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

, where he earned a B.A. (1950), M.A. (1952), and Ph.D. (1956) in economics. Between 1955 and 1963 he taught economics at the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with highly selective ad ...

and in 1960 published ''The Political Economy of National Security.'' In 1963, he moved to the RAND Corporation

The RAND Corporation (from the phrase "research and development") is an American nonprofit global policy think tank created in 1948 by Douglas Aircraft Company to offer research and analysis to the United States Armed Forces. It is finance ...

, where he worked until 1969, in the later years as director of strategic studies.

Nixon Administration

In 1969, Schlesinger joined the Nixon administration as assistant director of theBureau of the Budget

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is the largest office within the Executive Office of the President of the United States (EOP). OMB's most prominent function is to produce the president's budget, but it also examines agency programs, poli ...

, devoting most of his time to Defense matters. In 1971, President Nixon appointed Schlesinger a member of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and designated him as chairman. Serving in this position for about a year and a half, Schlesinger instituted extensive organizational and management changes in an effort to improve the AEC's regulatory performance.

CIA Director

Schlesinger was CIA Director from February 2, 1973, to July 2, 1973. He was succeeded byWilliam Colby

William Egan Colby (January 4, 1920 – May 6, 1996) was an American intelligence officer who served as Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) from September 1973 to January 1976.

During World War II Colby served with the Office of Strateg ...

.

Schlesinger was extremely unpopular with CIA staff, as he reduced CIA staff by 7%, and was considered a Nixon loyalist seeking to make the agency more obedient to Nixon. He had a CCTV camera installed near his official portrait at the CIA headquarters in Langley, Va., as it was believed that vandalism of the portrait by disgruntled staff was likely.

Secretary of Defense (1973–1975)

Schlesinger left the CIA to become Secretary of Defense on July 2, aged 44. As a university professor, researcher at Rand, and government official in three agencies, he had acquired an impressive resume in national security affairs.Nuclear strategy

Shortly after assuming office, Schlesinger outlined the basic objectives that would guide his administration: maintain a "strong defense establishment"; "assure the military balance so necessary to deterrence and a more enduring peace"; obtain for members of the military "the respect, dignity and support that are their due"; assume "an . . . obligation to use our citizens' resources wisely"; and "become increasingly competitive with potential adversaries.... must not be forced out of the market on land, at sea, or in the air.

Shortly after assuming office, Schlesinger outlined the basic objectives that would guide his administration: maintain a "strong defense establishment"; "assure the military balance so necessary to deterrence and a more enduring peace"; obtain for members of the military "the respect, dignity and support that are their due"; assume "an . . . obligation to use our citizens' resources wisely"; and "become increasingly competitive with potential adversaries.... must not be forced out of the market on land, at sea, or in the air. Eli Whitney

Eli Whitney Jr. (December 8, 1765January 8, 1825) was an American inventor, widely known for inventing the cotton gin, one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution that shaped the economy of the Antebellum South.

Although Whitney hi ...

belongs to us, not to our competitors." In particular, Schlesinger saw a need in the post-Vietnam era to restore the morale and prestige of the military services; modernize strategic doctrine and programs; step up research and development; and shore up a DoD budget that had been declining since 1968.

Analyzing strategy, Schlesinger maintained that the theory and practice of the 1950s and 1960s had been overtaken by events, particularly the rise of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

to virtual nuclear parity with the United States and the effect this development had on the concept of deterrence. Schlesinger believed that "deterrence is not a substitute for defense; defense capabilities, representing the potential for effective counteraction, are the essential condition of deterrence." He had grave doubts about the assured destruction strategy, which relied on massive nuclear attacks against an enemy's urban-industrial areas. Credible strategic nuclear deterrence, the secretary felt, depended on fulfilling several conditions: maintaining essential equivalence with the Soviet Union in force effectiveness; maintaining a highly survivable force that could be withheld or targeted against an enemy's economic base in order to deter coercive or desperation attacks against U.S. population or economic targets; establishing a fast-response force that could act to deter additional enemy attacks; and establishing a range of capabilities sufficient to convince all nations that the United States was equal to its strongest competitors.

To meet these needs, Schlesinger built on existing ideas in developing a flexible response nuclear strategy, which, with the President's approval, he made public by early 1974. The United States, Schlesinger said, needed the ability, in the event of a nuclear attack, to respond so as to "limit the chances of uncontrolled escalation" and "hit meaningful targets" without causing widespread collateral damage. The nation's assured destruction force would be withheld in the hope that the enemy would not attack U.S. cities. In rejecting assured destruction, Schlesinger quoted President Nixon: "Should a President, in the event of a nuclear attack, be left with the single option of ordering the mass destruction of enemy civilians, in the face of the certainty that it would be followed by the mass slaughter of Americans?"

With this approach, Schlesinger moved to a partial counterforce

In nuclear strategy, a counterforce target is one that has a military value, such as a launch silo for intercontinental ballistic missiles, an airbase at which nuclear-armed bombers are stationed, a homeport for ballistic missile submarines, or ...

policy, emphasizing Soviet military targets such as ICBM

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons ...

missile installations, avoiding initial attacks on population centers, and minimizing unintended collateral damage. He explicitly disavowed any intention to acquire a destabilizing first-strike capability against the USSR. But he wanted "an offensive capability of such size and composition that all will perceive it as in overall balance with the strategic forces of any potential opponent."

Schlesinger devoted much attention to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

, citing the need to strengthen its conventional capabilities. He rejected the old assumption that NATO did not need a direct counter to Warsaw Pact conventional forces because it could rely on tactical and strategic nuclear weapons, noting that the approximate nuclear parity between the United States and the Soviets in the 1970s made this stand inappropriate. He rejected the argument that NATO could not afford a conventional counterweight to Warsaw Pact forces. In his discussions with NATO leaders, Schlesinger promoted the concept of burden-sharing, stressing the troubles that the United States faced in the mid-1970s because of an unfavorable balance of international payments. He urged qualitative improvements in NATO forces, including equipment standardization, and an increase in defense spending by NATO governments of up to five percent of their gross national product.

Yom Kippur War and Cyprus crisis

Schlesinger had an abiding interest in strategic theory, but he also had to deal with a succession of immediate crises that tested his administrative and political skills. In October 1973, three months after he took office, Arab countries launched a surprise attack on Israel and started theYom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, was an armed conflict fought from October 6 to 25, 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab states led by E ...

. A few days after the war started, with Israel not faring as well as expected militarily, the Soviets resupplying some Arab countries and the Israeli government having authorized the use and assembly of nuclear weapons, the United States began an overt operation to airlift

An airlift is the organized delivery of supplies or personnel primarily via military transport aircraft.

Airlifting consists of two distinct types: strategic and tactical. Typically, strategic airlifting involves moving material long distan ...

materiel to Israel. As Schlesinger explained, the initial U.S. policy to avoid direct involvement rested on the assumption that Israel would win quickly. But when it became clear that the Israelis faced more formidable military forces than anticipated, and could not meet their own resupply arrangements, the United States took up the burden. According to Henry Kissinger, with the president's authority, the directive was made to resupply Israel with the needed equipment and eliminate State Department delay. "It was alleged that the airlift was deliberately delayed as a maneuver to pressure Israel." Schlesinger rejected charges that the Defense Department delayed the resupply effort to avoid irritating the Arab states and that he had had a serious disagreement over this matter with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

. Eventually the combatants agreed to a cease-fire, but not before the Soviet Union threatened to intervene on the Arab side and the United States declared a higher level worldwide alert of its forces.

Another crisis flared in July 1974 within the NATO alliance when Turkish forces, concerned about the long-term lack of safety for the minority Turkish community, invaded Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

after the Cypriot National Guard, supported by the government of Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

, overthrew President Archbishop Makarios

Makarios III ( el, Μακάριος Γ΄; born Michael Christodoulou Mouskos) (Greek: Μιχαήλ Χριστοδούλου Μούσκος) (13 August 1913 – 3 August 1977) was a Cypriot politician, archbishop and primate who served as ...

. When the fighting stopped, the Turks held the northern portion of country and about 40 percent of the island. Turkey's military action caused controversy in the United States, because of protests and lobbying by supporters of the Greek Cypriot side and, officially, because Turkish forces used some U.S.-supplied military equipment intended solely for NATO purposes.

He felt the Turks had overstepped the bounds of legitimate NATO interests in Cyprus and suggested that the United States might have to reexamine its military aid program to Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

. During this time, President Gerald R. Ford had succeeded Nixon after his resignation; eventually Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

made it clear with two presidential vetoes that they favored continued military assistance to Turkey as a valued NATO ally, but Congress overrode both vetoes and in December 1974 prohibited such aid, which instituted an arms embargo that lasted five years.

Indochina

The last phase of the

The last phase of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

occurred during Schlesinger's tenure. Although all U.S. combat forces had left South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam ( vi, Việt Nam Cộng hòa), was a state in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975, the period when the southern portion of Vietnam was a member of the Western Bloc during part of th ...

in the spring of 1973, the United States continued to maintain a military presence in other areas of Southeast Asia. Some senators criticized Schlesinger and questioned him sharply during his confirmation hearings in June 1973 after he stated that he would recommend resumption of U.S. bombing in North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; vi, Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa), was a socialist state supported by the Soviet Union (USSR) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Southeast Asia that existed f ...

and Laos

Laos (, ''Lāo'' )), officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic ( Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, French: République démocratique populaire lao), is a socialist s ...

if North Vietnam launched a major offensive against South Vietnam. However, when the North Vietnamese began their 1975 Spring Offensive

The 1975 spring offensive ( vi, chiến dịch mùa Xuân 1975), officially known as the general offensive and uprising of spring 1975 ( vi, Tổng tiến công và nổi dậy mùa Xuân 1975) was the final North Vietnamese campaign in the Vi ...

, the United States could do little to help the South Vietnamese, who collapsed completely as the North Vietnamese captured Saigon in late April. Schlesinger announced early in the morning of 29 April 1975 the evacuation from Saigon by helicopter of the last U.S. diplomatic, military and civilian personnel.

Only one other notable event remained in the Indochina drama. In May 1975 Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979 ...

forces boarded and captured the crew of the '' Mayaguez'', an unarmed U.S.-registered freighter. The United States bombarded military and fuel installations on the Cambodian mainland while Marines landed by helicopter on an offshore island to rescue the crew. The 39 captives were retrieved, but the operation cost the lives of 41 U.S. military personnel. Nevertheless, the majority of the American people seemed to approve of the administration's decisive action.

Defense budget

Unsurprisingly, given his determination to build up U.S. strategic and conventional forces, Schlesinger devoted much time and effort to the Defense budget. Even before becoming secretary, in a speech in San Francisco in September 1972, he warned that it was time "to call a halt to the self-defeating game of cutting defense outlays, this process, that seems to have become addictive, of chopping away year after year." Shortly after he took office, he complained about "the post-war follies" of Defense budget-cutting. Later he outlined the facts about the DoD budget: In real terms it had been reduced by one-third since FY 1968; it was one-eighth below the pre-Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

FY 1964 budget; purchases of equipment, consumables, and R&D were down 45 percent from the wartime peak and about $10 billion in constant dollars below the prewar level; Defense now absorbed about 6 percent of the gross national product, the lowest percentage since before the Korean War; military manpower was at the lowest point since before the Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top:{ ...

; and Defense spending amounted to about 17 percent of total national expenditures, the lowest since before the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941. Armed with these statistics, and alarmed by continuing Soviet weapon advances, Schlesinger became a vigorous advocate of larger DoD budgets. But he had little success. For FY 1975, Congress provided TOA of $86.1 billion, compared with $81.6 billion in FY 1974; for FY 1976, the amount was $95.6 billion, an increase of 3.4 percent, but in real terms slightly less than it had been in FY 1955.

Dismissal as Secretary of Defense

Schlesinger's insistence on higher defense budgets, his disagreements within the administration and with Congress on this issue, and his differences with Secretary of State Kissinger all contributed to his dismissal by President Ford in November 1975. Schlesinger's legacy included the development of the close-air support aircraft the

Schlesinger's insistence on higher defense budgets, his disagreements within the administration and with Congress on this issue, and his differences with Secretary of State Kissinger all contributed to his dismissal by President Ford in November 1975. Schlesinger's legacy included the development of the close-air support aircraft the A-10

The Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II is a single-seat, twin-turbofan, straight-wing, subsonic attack aircraft developed by Fairchild Republic for the United States Air Force (USAF). In service since 1976, it is named for the Republic ...

and the lightweight F-16

The General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon is a single-engine multirole fighter aircraft originally developed by General Dynamics for the United States Air Force (USAF). Designed as an air superiority day fighter, it evolved into a successf ...

fighter. Kissinger strongly supported the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks

The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) were two rounds of bilateral conferences and corresponding international treaties involving the United States and the Soviet Union. The Cold War superpowers dealt with arms control in two rounds of ...

process, while Schlesinger wanted assurances that arms control agreements would not put the United States in a strategic position inferior to the Soviet Union. The secretary's harsh criticism of some congressional leaders dismayed President Ford, who was more willing than Schlesinger to compromise on the Defense budget. On 2 November 1975, the president dismissed Schlesinger and made other personnel changes. Kissinger lost his position as special assistant to the President for national security affairs but remained as Secretary of State. Schlesinger left office on 19 November 1975, explaining his departure in terms of his budgetary differences with the White House.

The main reason behind Schlesinger's dismissal, though at the time unreported, was his insubordination toward President Ford. During the ''Mayaguez'' incident, Ford ordered several retaliatory strikes against Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand ...

. Schlesinger told Ford the first strike was carried out, but Ford later learned that Schlesinger, who disagreed with the order, had none of them carried out. According to Bob Woodward

Robert Upshur Woodward (born March 26, 1943) is an American investigative journalist. He started working for '' The Washington Post'' as a reporter in 1971 and now holds the title of associate editor.

While a young reporter for ''The Washingt ...

's 1999 book, ''Shadow

A shadow is a dark area where light from a light source is blocked by an opaque object. It occupies all of the three-dimensional volume behind an object with light in front of it. The cross section of a shadow is a two- dimensional silhouett ...

'', Ford let the incident go, but when Schlesinger committed further insubordination on other matters, Ford fired him. Woodward observes, "The United States had just lost a war for the first time. That the president and the secretary of defense could not agree on who was in charge was appalling. hisunpublicized breakdown in the military chain of command was perhaps the most significant scandal of the Ford presidency." Schlesinger had also disobeyed Ford when told to send as many military aircraft as possible to evacuate South Vietnam. Schlesinger disagreed with doing so and did not send the aircraft. Woodward says that an elected president, which Ford was not, would never have tolerated the insubordination.

In spite of the controversy surrounding both his tenure and dismissal, Schlesinger was by most accounts an able secretary of defense. A serious and perceptive thinker on nuclear strategy, he was determined that the United States not fall seriously behind the Soviet Union in conventional and nuclear forces and devoted himself to modernization of defense policies and programs. He got along well with the military leadership because he proposed to give them more resources, consulted with them regularly, and shared many of their views. Because he was a forthright speaker who could be blunt in his opinions and did not enjoy the personal rapport with legislators that prior Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird

Melvin Robert Laird Jr. (September 1, 1922 – November 16, 2016) was an American politician, writer and statesman. He was a U.S. congressman from Wisconsin from 1953 to 1969 before serving as Secretary of Defense from 1969 to 1973 under Pres ...

had, his relations with Congress were often strained. A majority of its members may have approved Schlesinger's strategic plans, but they kept a tight rein on the money for his programs.

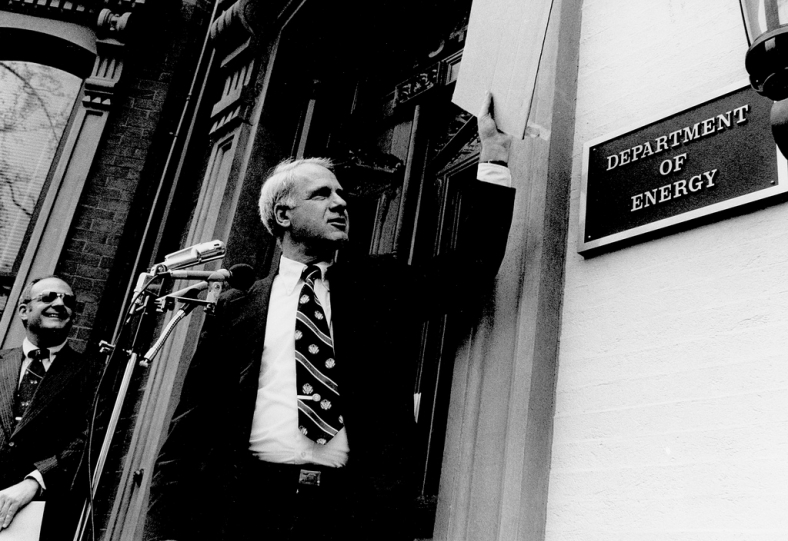

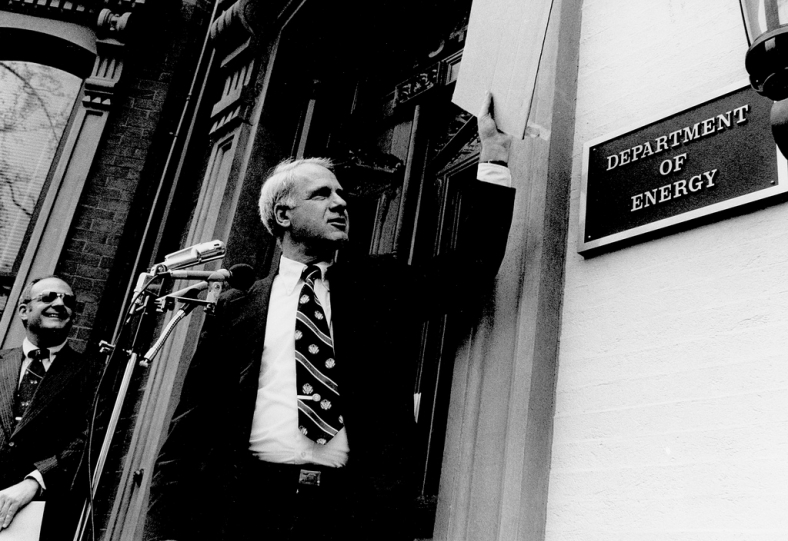

Secretary of Energy (1977–1979)

After leaving the Pentagon, Schlesinger wrote and spoke forcefully about national security issues, especially the Soviet threat and the need for the United States to maintain adequate defenses. When

After leaving the Pentagon, Schlesinger wrote and spoke forcefully about national security issues, especially the Soviet threat and the need for the United States to maintain adequate defenses. When Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

became president in January 1977 he appointed Schlesinger, a Republican, as his special adviser on energy and subsequently as the first Secretary of Energy

The United States secretary of energy is the head of the United States Department of Energy, a member of the Cabinet of the United States, and fifteenth in the presidential line of succession. The position was created on October 1, 1977, when Pr ...

in October 1977. According to one account, "Schlesinger impressed candidate Jimmy Carter with his brains, his high-level experience... and with secrets regarding the defense spending vacillations of his old boss, Ford, just in time for the presidential debates." Glastris, Paulbr>The powers that shouldn't be; five Washington insiders the next Democratic president shouldn't hire''

The Washington Monthly

''Washington Monthly'' is a bimonthly, nonprofit magazine of United States politics and government that is based in Washington, D.C. The magazine is known for its annual ranking of American colleges and universities, which serves as an alterna ...

'' (October 1987)

As Energy Secretary, Schlesinger launched the Department's Carbon Dioxide Effects and Assessment Program shortly after the creation of that department in 1977. Secretary Schlesinger also oversaw the integration of the energy powers of more than 50 agencies, such as the Federal Energy Administration The Federal Energy Administration (FEA) was a United States government organization created in 1974 to address the 1970s energy crisis, and specifically the 1973 oil crisis.Staff report (May 8, 1974). Energy Crisis Still With Us, Nixon Warns. ''Los ...

and the Federal Power Commission

The Federal Power Commission (FPC) was an independent commission of the United States government, originally organized on June 23, 1930, with five members nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. The FPC was originally created in ...

. In July 1979, Carter replaced him as part of a broader Cabinet shakeup. According to journalist Paul Glastris Paul Glastris is an American journalist and political columnist. Glastris is the current editor-in-chief of the ''Washington Monthly'' and was President Bill Clinton's chief speechwriter from September 1998 to the end of his presidency in early 2 ...

, "Carter fired Schlesinger in 1979 in part for the same reason Gerald Ford had—he was unbearably arrogant and impatient with lesser minds who disagreed with him, and hence inept at dealing with Congress."

Climate change memo

On July 7, 1977 Schlesinger read and attached a note to a memo about the catastrophic effects ofclimate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

entitled "Release of Fossil CO2 and the Possibility of a Catastrophic Climate Change", his note read:

My view is that the policy implications of this issue are still too uncertain to warrant Presidential involvement and policy initiatives.The note encouraged then President Carter to dismiss the issue, and therefore contributed to the long-held dismissal of climate-related discourse and action within the US government.

Post-government activities

After leaving the Energy Department, Schlesinger resumed his writing and speaking career, including the 1994 lecture at the Waldo Family Lecture on International Relations at

After leaving the Energy Department, Schlesinger resumed his writing and speaking career, including the 1994 lecture at the Waldo Family Lecture on International Relations at Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University (Old Dominion or ODU) is a public research university in Norfolk, Virginia. It was established in 1930 as the Norfolk Division of the College of William & Mary and is now one of the largest universities in Virginia w ...

. He was employed as a senior adviser to Lehman Brothers, Kuhn, Loeb Inc.

Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. ( ) was an American global financial services firm founded in 1847. Before filing for bankruptcy in 2008, Lehman was the fourth-largest investment bank in the United States (behind Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, ...

, of New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. He advised Congressman and presidential candidate Richard Gephardt

Richard Andrew Gephardt (; born January 31, 1941) is an American attorney, lobbyist, and politician who served as a United States Representative from Missouri from 1977 to 2005. A member of the Democratic Party, he was House Majority Leader fro ...

in 1988

File:1988 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The oil platform Piper Alpha explodes and collapses in the North Sea, killing 165 workers; The USS Vincennes (CG-49) mistakenly shoots down Iran Air Flight 655; Australia celebrates its Bicenten ...

.

In 1995, he was the Chairman of the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA). They wrote a report in conjunction with the National Research Council called "The Global Positioning System: Charting the Future" The report advocated for the opening GPS up to the private sector.

On February 8, 2002, he appeared at a hearing before the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs is the chief oversight committee of the United States Senate. It has jurisdiction over matters related to the Department of Homeland Security and other homeland s ...

in support of the creation of a commission to investigate the 9/11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commerci ...

.

On June 11, 2002, he was appointed by U.S. President George W. Bush to the Homeland Security Advisory Council The Homeland Security Advisory Council (HSAC) is part of the Executive Office of the President of the United States. It was created by an Executive Order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the Unite ...

. He also served as a consultant to the United States Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense (DoD, USDOD or DOD) is an executive branch department of the federal government charged with coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government directly related to national sec ...

, and was a member of the Defense Policy Board

The Defense Policy Board Advisory Committee, also referred to as the Defense Policy Board (DPBAC or DPB), is a federal advisory committee to the United States Department of Defense. Their charter is available online through the office of the Dir ...

.

In 2004, he served as chairman to the Independent Panel to Review DoD Detention Operations.

On January 5, 2006, he participated in a meeting at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

of former Secretaries of Defense and State to discuss United States foreign policy with Bush administration officials. On January 31, 2006, he was appointed by the Secretary of State to be a member of the Arms Control and Nonproliferation Advisory Board. On May 2, 2006, he was named to be a co-chairman of a Defense Science Board study on DOD Energy Strategy. He was an honorary chairman of The OSS Society. He was also a Bilderberg Group

The Bilderberg meeting (also known as the Bilderberg Group) is an annual off-the-record conference established in 1954 to foster dialogue between Europe and North America. The group's agenda, originally to prevent another world war, is now defi ...

attendee in 2008.

In 2007, NASA Administrator Michael Griffin appointed Schlesinger to be the Chairman of the National Space-based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) Advisory Board. The "PNT Board" is composed of recognized Global Positioning System (GPS) experts from outside the U.S. government that advise the Deputy Secretary level PNT Executive Committee in their oversight management of the GPS constellation and its governmental augmentationsOn June 5, 2008, Defense Secretary Robert Gates appointed Schlesinger to head a task force to ensure the "highest levels" of control over nuclear weapons. The purpose of the review was to prevent a repeat of recent incidents where control was lost over components of nuclear weapons, and even over nuclear weapons themselves. Schlesinger was chairman of the Board of Trustees of MITRE, The MITRE Corporation, having served on it from 1985 until his death in 2014; on the advisory board of ''

The National Interest

''The National Interest'' (''TNI'') is an American bimonthly international relations magazine edited by American journalist Jacob Heilbrunn and published by the Center for the National Interest, a public policy think tank based in Washington, ...

''; a Director of BNFL, Inc., Peabody Energy

Peabody Energy is a coal mining and energy company headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri. Its primary business consists of the mining, sale, and distribution of coal, which is purchased for use in electricity generation and steelmaking. Peabody ...

, Sandia Corporation

Sandia National Laboratories (SNL), also known as Sandia, is one of three research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy's National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). Headquartered in Kirtland Air Force Bas ...

, Seven Seas Petroleum Company, chairman of the executive committee of The Nixon Center. He was also on the advisory board of GeoSynFuels, LLC. Schlesinger penned a number of opinion pieces on global warming

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

, expressing a strongly skeptical position.

Peak oil

Schlesinger raised awareness of thepeak oil

Peak oil is the hypothetical point in time when the maximum rate of global oil production is reached, after which it is argued that production will begin an irreversible decline. It is related to the distinct concept of oil depletion; whil ...

issue and supports facing it. In the keynote speech at a 2007 conference hosted by the Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas in Cork, Schlesinger said that oil industry executives now privately concede that the world faces an imminent oil production peak. In his 2010 ASPO-USA keynote speech, Schlesinger observed that the Peak Oil

Peak oil is the hypothetical point in time when the maximum rate of global oil production is reached, after which it is argued that production will begin an irreversible decline. It is related to the distinct concept of oil depletion; whil ...

debate was over. He warned of political inaction as a major hindrance, like those in Pompeii

Pompeii (, ) was an ancient city located in what is now the ''comune'' of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area (e.g. at Boscoreale, Stabiae), was burie ...

before the eruption of Mount Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ; it, Vesuvio ; nap, 'O Vesuvio , also or ; la, Vesuvius , also , or ) is a somma-stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of ...

.

On June 5, 2008, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates

Robert Michael Gates (born September 25, 1943) is an American intelligence analyst and university president who served as the 22nd United States secretary of defense from 2006 to 2011. He was originally appointed by president George W. Bush a ...

announced that he had asked Schlesinger to lead a senior-level task force to recommend improvements in the stewardship and operation of nuclear weapons, delivery vehicles and sensitive components by the US DoD following the 2007 United States Air Force nuclear weapons incident

On 29 August 2007, six AGM-129 ACM cruise missiles, each loaded with a W80-1 variable yield nuclear warhead, were mistakenly loaded onto a United States Air Force (USAF) B-52H heavy bomber at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota and transport ...

. Members of the task force came from the Defense Policy Board and the Defense Science Board.

Personal life

In 1954, Schlesinger married Rachel Line Mellinger (February 27, 1930 – October 11, 1995); they had eight children: Cora (1955), Charles (1956), Ann (1958), William (1959), Emily (1961), Thomas (1964), Clara (1966) and James (1970). Though raised in a Jewish household, Schlesinger converted toLutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

as an adult.

Rachel Schlesinger was an accomplished violinist and board member of the Arlington Symphony. In the early 1990s, she was a leader in the fundraising effort to create a premier performing arts center on the Virginia side of the Potomac River. She died from cancer before seeing the center's completion. After her death, Dr. Schlesinger donated $1 million to have the center named in his wife's memory. The Rachel M. Schlesinger Concert Hall and Arts Center at Northern Virginia Community College

Northern Virginia Community College (NVCC; informally known as NOVA) is a public community college composed of six campuses and four centers in the Northern Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C. Northern Virginia Community College is the third- ...

, Alexandria Campus opened in September, 2001. It is an up-to-date building that features the Mary Baker Collier Theatre, the Margaret W. and Joseph L. Fisher Art Gallery, the Wachovia Forum and Seminar Room spaces. Clients of the Schlesinger Center include the Alexandria Symphony, the United States Marine Band

The United States Marine Band is the premier band of the United States Marine Corps. Established by act of Congress on July 11, 1798, it is the oldest of the United States military bands and the oldest professional musical organization in th ...

, "The President's Own", and the U.S. Marine Chamber Orchestra, the United States Army Band

The United States Army Band, also known as "Pershing's Own", is the premier musical organization of the United States Army, founded in 1922. There are currently nine official performing ensembles in the unit: The U.S. Army Concert Band, The U.S. A ...

, "Pershing's Own", and the U.S. Army Strings, the United States Navy Band

The United States Navy Band, based at the Washington Navy Yard in Washington, D.C., has served as the official musical organization of the U.S. Navy since 1925. The U.S. Navy Band serves the ceremonial needs at the seat of government, performi ...

, the New Dominion Chorale, the American Balalaika Symphony, Festivals of Music, various ethnic groups and many others.

Schlesinger worked consistently with distinction long after his government and academic experiences, serving on numerous governmental advisory boards until only weeks before his death at the age of 85.

He was buried at Ferncliff Cemetery in Springfield, Ohio.

Selected publications

* Schlesinger, James R. ''America at Century's End''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989. * Schlesinger, James R. ''American Security and Energy Policy''. Manhattan, Kan: Kansas State University, 1980. * Schlesinger, James R. ''Defense Planning and Budgeting: The Issue of Centralized Control''. Washington: Industrial College of the Armed Forces, 1968. * Schlesinger, James R. ''The Political Economy of National Security; A Study of the Economic Aspects of the Contemporary Power Struggle''. New York: Praeger, 1960.In popular culture

Schlesinger is referred to in the book ''Peril'' byBob Woodward

Robert Upshur Woodward (born March 26, 1943) is an American investigative journalist. He started working for '' The Washington Post'' as a reporter in 1971 and now holds the title of associate editor.

While a young reporter for ''The Washingt ...

and Robert Costa concerning actions taken by Mark Milley

Mark Alexander Milley (born June 20, 1958) is a United States Army general who serves as the 20th chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He previously served as the 39th chief of staff of the Army from August 14, 2015 to August 9, 2019, and hel ...

, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under Presidents Trump and Biden. According to the news outlet Slate, in 1974 "Schlesinger told Brown," then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, "to call him if he received any unusual orders from Nixon. Brown then told all the four-star officers in charge of the various military commands (including Strategic Air Command, which then had control of nuclear weapons) that they were not to carry out any 'execute orders' from the president unless Brown and Schlesinger first verified the orders." Senator Chuck Grassley

Charles Ernest Grassley (born September 17, 1933) is an American politician serving as the president pro tempore emeritus of the United States Senate, and the senior United States senator from Iowa, having held the seat since 1981. In 2022, h ...

recently called these actions "extralegal." According to Grassley, "'when President Nixon faced a crisis over impeachment and resignation, Secretary of Defense Schlesinger feared he might order an unprovoked nuclear strike,' he continued. 'So he reportedly took extralegal steps to prevent it.'" Both author Fred Kaplan and Grassley distinguish the actions of Schlesinger as Secretary of Defense

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in so ...

, from the actions of Mark Milley as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) is the presiding officer of the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS). The chairman is the highest-ranking and most senior military officer in the United States Armed Forces Chairman: app ...

, with Grassley saying: "Pulling a Milley is a very different kettle of fish. A four-star general can't "pull a Schlesinger". Schlesinger was at the top of the chain of command, just below the President. He kept the President's constitutional command icauthority firmly in civilian hands. Milley allegedly placed military hands—his hands—on controls that belong exclusively to the President."

References

External links

Annotated Bibliography for James R. Schlesinger from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

*Chris Mooney, ''

American Prospect

''The American Prospect'' is a daily online and bimonthly print American political and public policy magazine dedicated to American modern liberalism and progressivism. Based in Washington, D.C., ''The American Prospect'' says it "is devoted to ...

'', August 2005"Stop Him Before He Writes Again: Will someone please make James Schlesinger disclose his energy-industry ties next time he writes an anti-global warming op-ed?"

a 17 September 2007 interview

MITRE Biography

* * , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Schlesinger, James R. 1929 births 2014 deaths 20th-century American politicians Economists from New York (state) American Lutherans American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent American people of Austrian-Jewish descent Jewish American members of the Cabinet of the United States Carter administration cabinet members Chairmen of the United States Atomic Energy Commission Converts to Lutheranism from Judaism Directors of the Central Intelligence Agency English-only movement Ford administration cabinet members Harvard University alumni Horace Mann School alumni Mitre Corporation people New York (state) Republicans Nixon administration cabinet members Nixon administration personnel involved in the Watergate scandal Scientists from New York City United States Secretaries of Defense United States Secretaries of Energy University of Virginia faculty Foreign Policy Research Institute Writers from New York City