James Braid (surgeon) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Braid (19 June 1795 – 25 March 1860) was a Scottish

in 1854

, a Member of the Manchester Athenæum, and the Honorary Curator of the museum of the Manchester Natural History Society.

see ''Neurypnology'', pp. 16–20.

On the evening of Sunday, 10 April 1842, at St Jude's Church, Liverpool, the controversial cleric

On the evening of Sunday, 10 April 1842, at St Jude's Church, Liverpool, the controversial cleric

at which he presented its contents. Braid summarised and contrasted his own view with the other views prevailing at that time: ::"The various theories at present entertained regarding the phenomena of mesmerism may be arranged thus: First, those who believe them to be owing entirely to a system of collusion and delusion; and a great majority of society may be ranked under this head. Second, those who believe them to be real phenomena, but produced solely by imagination, sympathy, and imitation. Third, the animal magnetists, or those who believe in some magnetic medium set in motion as the exciting cause of the mesmeric phenomena. Fourth, those who have adopted my views, that the phenomena are solely attributable to a peculiar physiological state of the brain and the spinal cord."

By, at least, 28 February 1842, Braid was using "Neurohypnology" (which he later shortened to "Neurypnology"); and, in a public lecture on Saturday, 12 March 1842, at the Manchester Athenæum, Braid explained his terminological developments as follows:

::I therefore think it desirable to assume another name han animal magnetismfor the phenomena, and have adopted neurohypnology – a word which will at once convey to every one at all acquainted with Greek, that it is the rationale or doctrine of nervous sleep; sleep being the most constant attendant and natural analogy to the primary phenomena of mesmerism; the prefix "nervous" distinguishing it from natural sleep. There are only two other words I propose by way of innovation, and those are hypnotism for magnetism and mesmerism, and hypnotised for magnetised and mesmerised.

It is important to recognize three things; namely, that:

:(1) Braid was only using the term "sleep" metaphorically;

:(2) despite the constant mistaken assertions in the modern literature, Braid did not, even on a single occasion, ever use the term hypnosis; and

:(3) the term 'hypnosis' comes from the work of the Nancy School in the 1880s.

Although Braid was the first to use the terms '' hypnotism'', ''

By, at least, 28 February 1842, Braid was using "Neurohypnology" (which he later shortened to "Neurypnology"); and, in a public lecture on Saturday, 12 March 1842, at the Manchester Athenæum, Braid explained his terminological developments as follows:

::I therefore think it desirable to assume another name han animal magnetismfor the phenomena, and have adopted neurohypnology – a word which will at once convey to every one at all acquainted with Greek, that it is the rationale or doctrine of nervous sleep; sleep being the most constant attendant and natural analogy to the primary phenomena of mesmerism; the prefix "nervous" distinguishing it from natural sleep. There are only two other words I propose by way of innovation, and those are hypnotism for magnetism and mesmerism, and hypnotised for magnetised and mesmerised.

It is important to recognize three things; namely, that:

:(1) Braid was only using the term "sleep" metaphorically;

:(2) despite the constant mistaken assertions in the modern literature, Braid did not, even on a single occasion, ever use the term hypnosis; and

:(3) the term 'hypnosis' comes from the work of the Nancy School in the 1880s.

Although Braid was the first to use the terms '' hypnotism'', ''

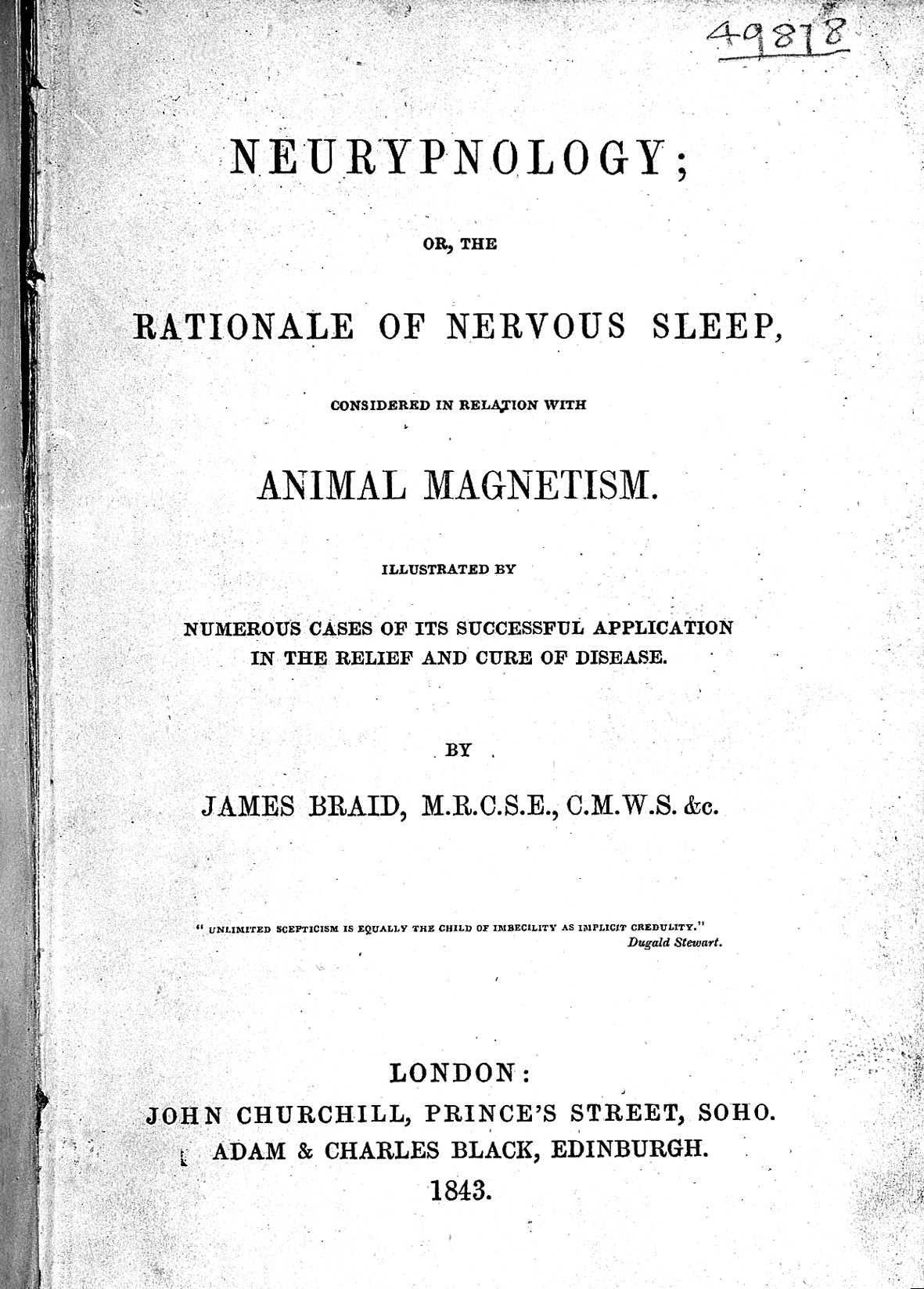

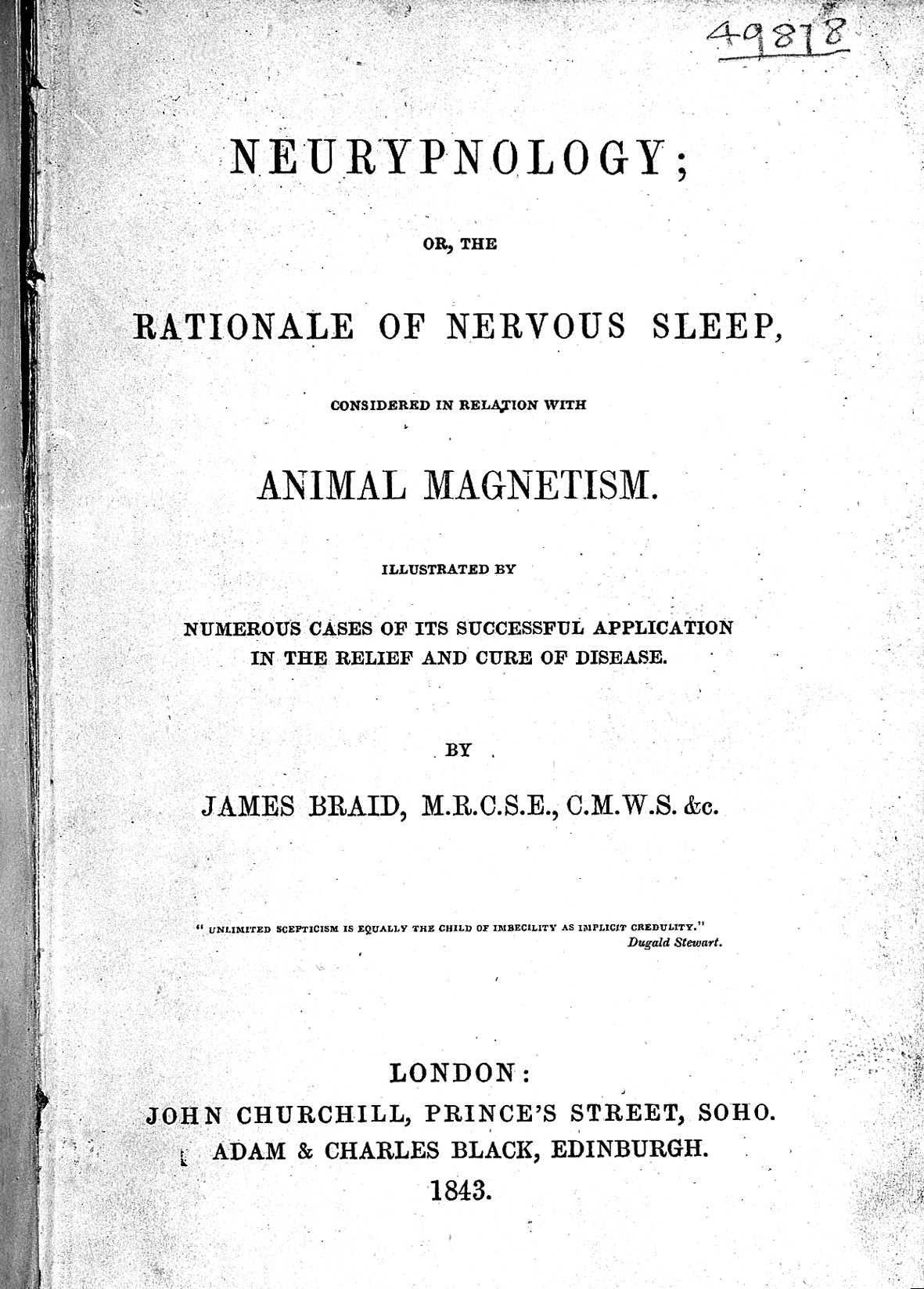

In 1843 he published ''Neurypnology; or the Rationale of Nervous Sleep'' ''Considered in Relation with Animal Magnetism...'', his first and only book-length exposition of his views. According to Bramwell, the work was popular from the outset, selling 800 copies within a few months of its publication.

Braid thought of hypnotism as producing a "nervous sleep" which differed from ordinary sleep. The most efficient way to produce it was through visual fixation on a small bright object held eighteen inches above and in front of the eyes. Braid regarded the physiological condition underlying hypnotism to be the over-exercising of the eye muscles through the straining of attention.

He completely rejected

In 1843 he published ''Neurypnology; or the Rationale of Nervous Sleep'' ''Considered in Relation with Animal Magnetism...'', his first and only book-length exposition of his views. According to Bramwell, the work was popular from the outset, selling 800 copies within a few months of its publication.

Braid thought of hypnotism as producing a "nervous sleep" which differed from ordinary sleep. The most efficient way to produce it was through visual fixation on a small bright object held eighteen inches above and in front of the eyes. Braid regarded the physiological condition underlying hypnotism to be the over-exercising of the eye muscles through the straining of attention.

He completely rejected

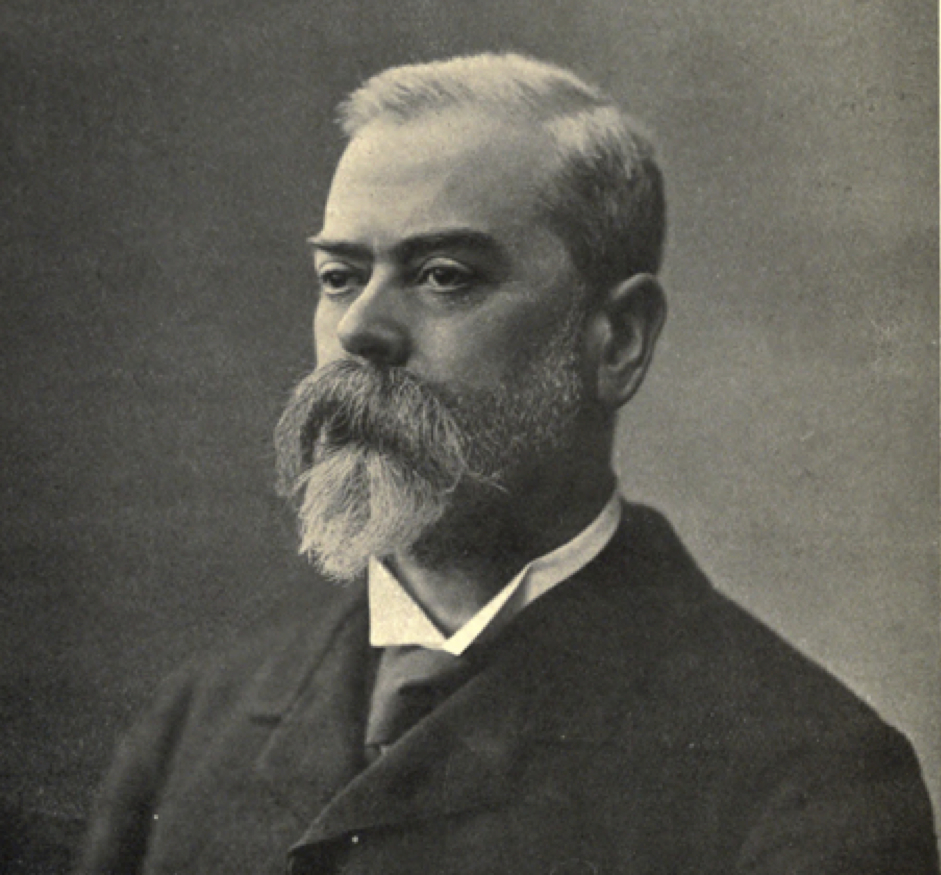

John Milne Bramwell, M.B. C.M., a talented specialist medical hypnotist and hypnotherapist himself, made a deep study of Braid's works and helped to revive and maintain Braid's legacy in Great Britain.

Bramwell had studied medicine at Edinburgh University in the same student cohort as Braid's grandson, Charles.

Consequently, due to his Edinburgh studies – especially those with John Hughes Bennett (1812–1875), author of ''The Mesmeric Mania of 1851, With a Physiological Explanation of the Phenomena Produced'' (1851) – Bramwell was very familiar with Braid and his work; and, more significantly, through Charles Braid, he also had unfettered access to those publications, records, papers, etc. of Braid that were still held by the Braid family. He was, perhaps, second only to

John Milne Bramwell, M.B. C.M., a talented specialist medical hypnotist and hypnotherapist himself, made a deep study of Braid's works and helped to revive and maintain Braid's legacy in Great Britain.

Bramwell had studied medicine at Edinburgh University in the same student cohort as Braid's grandson, Charles.

Consequently, due to his Edinburgh studies – especially those with John Hughes Bennett (1812–1875), author of ''The Mesmeric Mania of 1851, With a Physiological Explanation of the Phenomena Produced'' (1851) – Bramwell was very familiar with Braid and his work; and, more significantly, through Charles Braid, he also had unfettered access to those publications, records, papers, etc. of Braid that were still held by the Braid family. He was, perhaps, second only to

Braid, J., ''Satanic Agency and Mesmerism Reviewed, In A Letter to the Reverend H. Mc. Neile, A.M., of Liverpool, in Reply to a Sermon Preached by Him in St. Jude's Church, Liverpool, on Sunday, 10 April 1842, by James Braid, Surgeon, Manchester'', Simms and Dinham, and Galt and Anderson, (Manchester), 1842.

**A transcription of the text of Braid's pamphlet is presented at Volgyesi, (Winter 1955), "Discovery of Medical Hypnotism: Part 2"; Volgyesi's transcription is reprinted at Robertson (''Discovery of Hypnosis''), pp. 375–81. Another transcription is presented at Tinterow (''Foundations of Hypnosis''), pp. 317–30.

Both of these transcriptions have errors; a complete transcription, corrected with direct reference to an original copy of Braid's pamphlet, and annotated for the modern reader is a

Yeates (2013)

pp. 671–700.

N.B. Braid intended that his pamphlet was to be read in association with the newspaper report in the ''Macclesfield Courier'' of Saturday, 16 April 1842. A complete transcription of the newspaper article, annotated for the modern reader is at Yeates (2013), pp. 599–620.

Braid, J., ''Neurypnology or the Rationale of Nervous Sleep Considered in Relation with Animal Magnetism Illustrated by Numerous Cases of its Successful Application in the Relief and Cure of Disease'', John Churchill, (London), 1843.

**N.B. Braid's ''Errata'', detailing a number of important corrections that need to be made to the foregoing text, is o

the un-numbered page following p. 265.

Braid, J., "Observations on the Phenomena of Phreno-Mesmerism", ''The Medical Times'', Vol. 9, No. 216, (11 November 1843), pp. 74–75

reprinted a

''The Phrenological Journal, and Magazine of Moral Science'', Vol. 17, No. 78, (January 1844), pp. 18–26.

* Braid, J., "Observations on Mesmeric and Hypnotic Phenomena"

''The Medical Times'', Vol. 10, No. 238, (13 April 1844), pp. 31–32(20 April 1844), pp. 47–49.

Braid, J., "The Effect of Garlic on the Magnetic Needle", ''The Medical Times'', Vol. 10, No. 241, (4 May 1844), pp. 98–99.

* Braid, J., "Physiological Explanation of Some Mesmeric Phenomena"

''The Medical Times'', Vol. 10, No. 258, (31 August 1844), pp. 450–51

reprinted a

"Remarks on Mr. Simpson’s Letter on Hypnotism, published in the Phrenological Journal for July 1844", ''The Phrenological Journal, and Magazine of Moral Science'', Vol. 17, No. 81, (October 1844), pp. 359–65.

Braid, J., "Experimental Inquiry, to Determine whether Hypnotic and Mesmeric Manifestations can be Adduced in Proof of Phrenology", ''The Medical Times'', Vol. 11, No. 271, (30 November 1844), pp. 181–82.

* Braid, J. "Magic, Mesmerism, Hypnotism, etc., Historically and Physiologically Considered"

''Medical Times'', Vol. 11, No. 272, (7 December 1844), pp. 203–04No. 273, (14 December 1844), pp. 224–27No. 275, (28 December 1844), pp. 270–73No. 276, (4 January 1845), pp. 296–99No. 277, (11 January 1845), pp. 318–20No. 281, (8 February 1845), pp. 399–400No. 283, (22 February 1845), pp. 439–41.

Braid, J., "Experimental Inquiry to determine whether Hypnotic and Mesmeric Manifestations can be adduced in proof of Phrenology. By James Braid, M.R.C.S.E., Manchester. (From the ''Medical Times'', No. 271, 30 November 1844)", ''The Phrenological Journal, and Magazine of Moral Science'', Vol. 18, No. 83, (1845), pp. 156–62.

Braid, J., "Hypnotism" (Letter to the Editor), ''The Lancet'', Vol. 45, No. 1135, (31 May 1845), pp. 627–28.

* Braid, J., "The Power of the Mind over the Body: An Experimental Inquiry into the Nature and Cause of the Phenomena Attributed by Baron Reichenbach and Others to a "New Imponderable". By James Braid, M.R.C.S. Edin., &c., Manchester"

''The Medical Times'', Vol. 14, No. 350, (13 June 1846), pp. 214–16No. 352, (27 June 1846), pp. 252–54No. 353, (4 July 1846), pp. 273–74.

Braid, J., ''The Power of the Mind over the Body: An Experimental Inquiry into the Nature and Cause of the Phenomena Attributed by Baron Reichenbach and Others to a "New Imponderable"'', John Churchill, (London), 1846.

(A note, in Braid's handwriting, is at p. 3). * Braid, J., "Facts and Observations as to the Relative Value of Mesmeric and Hypnotic Coma, and Ethereal Narcotism, for the Mitigation or Entire Prevention of Pain during Surgical Operations"

''The Medical Times'', Vol. 15, No. 385, (13 February 1847), pp. 381–82Vol. 16, No. 387, (27 February 1847), pp. 10–11.

*

Braid, J., ''Observations on Trance; or, Human Hybernation'', John Churchill, (London), 1850.

Braid, J., "Electro-Biological Phenomena Physiologically and Psychologically Considered, by James Braid, M.R.C.S. Edinburgh, &c. &c. (Lecture delivered at the Royal Institution, Manchester, March 26, 1851)", ''The Monthly Journal of Medical Science'', Vol. 12, (June 1851), pp. 511–30.

Braid, J., ''Magic, Witchcraft, Animal Magnetism, Hypnotism, and Electro-Biology; Being a Digest of the Latest Views of the Author on these Subjects (Third Edition)'', John Churchill, (London), 1852.

* Braid, J., "Mysterious Table Moving", ''The Manchester Examiner and Times'', Vol. 5, No. 469, (Saturday, 30 April 1853), p. 5, col.B.

Braid, J., "Hypnotic Therapeutics, Illustrated by Cases. By JAMES BRAID, Esq., Surgeon, of Manchester", ''The Monthly Journal of Medical Science'', Vol. 17, (July 1853), pp. 14–47.

* Braid, J., "Letter to Michael Faraday on the phenomenon of "Table Turning" ritten on 22 August 1853, reprinted at pp. 560–61 of James, F.A.J.L., ''The Correspondence of Michael Faraday, Volume 4: January 1849 – October 1855'', Institution of Electrical Engineers, (London), 1999.

Braid, J., ''Hypnotic Therapeutics, Illustrated by Cases: With an Appendix on Table-Moving and Spirit-Rapping. Reprinted from the Monthly Journal of Medical Science for July 1853'', Murray and Gibbs, (Edinburgh), 1853

Braid, J., "On the Nature and Treatment of Certain Forms of Paralysis", ''Association Medical Journal'', Vol. 3, No. 141, (14 September 1855), pp. 848–55.

* Braid, J., ''The Physiology of Fascination, and the Critics Criticised'' two-part pamphlet John Murray, (Manchester), 1855. (The second part is a reply to attacks made in ''

Braid, J., "The Physiology of Fascination" (Miscellaneous Contribution to the Botany and Zoology including Physiology Section), ''Report of the Twenty-Fifth Meeting of the British Association; Held at Glasgow in September 1855'', John Murray, (London), 1856, pp. 120–21.

* Braid, J., "Chemical Analysis – The Rudgeley Poisoning", ''The Manchester Guardian'', No. 3051, (Saturday, 31 May 1856), p. 5, col.C.

Braid, J., "The Bite of the Tsetse: Arsenic Suggested as a Remedy (Letter to the Editor, written on 6 February 1858)", ''British Medical Journal'', Vol. 1, No. 59, (13 February 1858), p. 135.

Braid, J., "Arsenic as a Remedy for the Bite of the Tsetse, Etc. (Letter to the Editor, written in March 1858)", ''British Medical Journal'', Vol. 1, No. 63, (13 March 1858), pp. 214–15.

Braid, J., "Mr Braid on Hypnotism (Letter to the Editor, written on 21 February 1860)", ''The Medical Circular'', Vol. 16, (7 March 1860), pp. 158–59.

* Braid, J., "Hypnotism (Letter to the Editor, written on 26 February 1860)", ''The Critic'', Vol. 20, No. 505, (10 March 1860), p. 312.

''Der Hypnotismus. Ausgewählte Schriften von J. Braid. Deutsch herausgegeben von W. Preyer'' (''On Hypnotism; Selected Writings of J. Braid, in German, edited by W. Preyer.''), Verlag von Gebrüder Paetel, (Berlin), 1882.

Preyer, W., ''Der Hypnotismus: Vorlesungen gehalten an der K. Friedrich-Wilhelm’s-Universität zu Berlin, von W. Preyer. Nebst Anmerkungen und einer nachgelassenen Abhandlung von Braid aus dem Jahre 1845'' (''Hypnotism: Lectures delivered at the Emperor Frederick William’s University at Berlin by W. Preyer. With Notes and a Posthumous Paper of Braid From the Year 1845''), Urban & Schwarzenberg, 1890.

Preyer, W., ''Die Entdeckung des Hypnotismus. Dargestellt von W. Preyer … Nebst einer ungedruckten Original-Abhandlung von Braid in Deutscher Uebersetzung'' (''The Discovery of Hypnotism, presented by W. Preyer, together with a hithertofore unpublished paper by Braid in its German translation''), Verlag von Gebrüder Paetel, (Berlin), 1881.

* * Robertson, D. (ed), ''The Discovery of Hypnosis: The Complete Writings of James Braid, The Father of Hypnotherapy'', National Council for Hypnotherapy, (Studley), 2009

Braid, J. (Simon, J. trans.), ''Neurypnologie: Traité du Sommeil Nerveux, ou, Hypnotisme par James Braid; Traduit de l'anglais par le Dr Jules Simon; Avec preface de C. E. Brown-Séquard'' (''Neurypnology: Treatise on Nervous Sleep or Hypnotism by James Braid, translated from the English by Dr. Jules Simon, with a preface by C. E. Brown-Séquard.''), Adrien Delhaye et Émile Lecrosnier, (Paris), 1883.

* Tinterow, M.M., ''Foundations of Hypnosis: From Mesmer to Freud'', Charles C. Thomas, (Springfield), 1970. (contains transcription of Braid's "Satanic Agency and Mesmerism") * Volgyesi, F.A., "Discovery of Medical Hypnotism: J. Braid: "Satanic Agency and Mesmerism", etc. Preface and Interpretation by Dr. F. A. Volgyesi (Budapest). Part I", ''The British Journal of Medical Hypnotism'', Vol. 7, No. 1, (Autumn 1955), pp. 2–13; "Part 2", No. 2, (Winter 1955), pp. 25–34; "Part 3", No. 3, (Spring 1956), pp. 25–31.

Waite, A.E., ''Braid on Hypnotism: Neurypnology. A New Edition, Edited with an Introduction, Biographical and Bibliographical, Embodying the Author’s Later Views and Further Evidence on the Subject by Arthur Edward Waite'', George Redway, (London), 1899.

**A re-issue of the 1899 edition of Waite, with an additional foreword by "J.H. Conn, M.D., Pres., Society for Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, The Johns Hopkins University Medical School, Baltomore, Md." was released in 1960 as: Braid, J., ''Braid on Hypnotism: The Beginnings of Modern Hypnosis'', The Julian Press, (New York), 1960. N.B.: The (1960) book's title page, cover, and dust jacket all mistakenly refer to "James Braid, M.D." (instead of the 1899 original's "James Braid, M.R.C.S., C.M.W.S., &c.").

Anon, "Jenny Lind and the Mesmerist", ''The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser'', (Wednesday, 26 January 1848), p.1.

* Anon, "On Animal Magnetism", ''The London Medical Gazette'', Vol. 20

No. 533, (17 February 1838), pp. 824–29No. 534; (24 February 1838), pp. 856–60No. 537, (17 March 1838), pp. 986–91

an

No. 538, (24 March 1838), pp. 1034–37.

Anon, "Abstract of a Lecture on Electro-Biology, delivered at the Royal Institution, Manchester, on the 26th March 1851. By James Braid, M.R.C.S., Edinburgh, C.M.W.S., &c. &c.", ''Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal'', Vol. 76, No. 188, (1 July 1851), pp. 239–48.

* Anon, "Hypnotism – Important Medical Discovery", ''The New York Herald'', (Thursday, 5 January 1860), p. 5, col B.

Anon, "Sudden Death of Mr. James Braid, Surgeon, of Manchester", ''The Lancet'', Vol. 75, No. 1909, (31 March 1860), p. 335.

* Bernheim, H., "A propos de l'étude sur James Braid par le Dr. Milne Bramwell, et de son rapport lu au Congrès de Bruxelles ith Regard to the Study of James Braid by Dr. Milne Bramwell, and his Report Read to the Congress at Brussels

''Revue de l'Hypnotisme Expérimentale & Thérapeutique'', Vol. 12, No. 5, (November 1897), pp. 137–45.

* Bramwell, J.M., "James Braid: His Work and Writings", ''Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research'', Vol. 12, Supplement, (1896), pp. 127–66. * Bramwell, J.M., "Personally Observed Hypnotic Phenomena", ''Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research'', Vol. 12, Supplement, (1896), pp. 176–203.

Bramwell, J.M., "James Braid: Surgeon and Hypnotist", ''Brain'', Vol. 19, No. 1, (1896), pp. 90–116.

Bramwell, J.M., "On the Evolution of Hypnotic Theory", ''Brain'', Vol. 19, No. 4, (1896), pp. 459–568.

* Bramwell, M., "James Braid: son œuvre et ses écrits ames Braid: His Work and Writings, ''Revue de l'Hypnotisme Expérimentale & Thérapeutique'', Vol. 12

No. 1, (July 1897), pp. 27–30No. 2, (August 1897), pp. 60–63(September 1897), pp. 87–91

* Bramwell, M., "La Valeur Therapeutique de l'Hypnotisme et de la Suggestion he Therapeutic Value of Hypnotism and Suggestion, ''Revue de l'Hypnotisme Expérimentale & Thérapeutique''

Vol. 12, No. 5, (November 1897), pp. 129–37

* Bramwell, J.M., "James Braid et la Suggestion: Réponse à M. le Professeur Bernheim (de Nancy) par M. le Dr. Milne-Bramwell (de Londres) ames Braid and Suggestion: A Response to Professor Bernheim (of Nancy) from Dr. Milne-Bramwell (of London), ''Revue de l'Hypnotisme Expérimentale & Thérapeutique''

Vol. 12, No. 12, (June 1898), pp. 353–61

Bramwell, J.M., ''Hypnotic and Post-hypnotic Appreciation of Time: Secondary and Multiplex Personalities'', ''Brain'', Vol. 23, No. 2, (1900), pp. 161–238.

* Bramwell, J.M., "Hypnotism: An Outline Sketch – Being a Lecture delivered before the King's College Medical Society", ''The Clinical Journal'', Vol. 20

No. 3, (Wednesday, 7 May 1902), pp. 41–45No. 4, (Wednesday, 14 May 1902), pp. 60–64

Bramwell, J.M., ''Hypnotism: Its History, Practice and Theory'', Grant Richards, (London), 1903.

Bramwell, J.M., ''Hypnotism: Its History, Practice and Theory (Second Edition)'', De La More Press, (London), 1906.

Bramwell, J.M., ''Hypnotism and Treatment by Suggestion'', Cassell & Co., (London), 1909. (Funk and Wagnalls, New York, 1910)

Bramwell, J.M., ''Hypnotism: Its History, Practice and Theory (Third Edition)'', William Rider & Son, (London), 1913.

* [https://archive.org/stream/autobiographical00clar#page/155/mode/1up Clarke, J.F., "A Strange Chapter in the History of Medicine", pp. 155–69 in Clarke, J.F., ''Autobiographical Recollections of the Medical Profession'', J. & A. Churchill, (London), 1874.]

Coates, James (1904), ''Human Magnetism; or, How to Hypnotise: A Practical Handbook for Students of Mesmerism'', London: Nichols & Co.

Easton, M.G., ''Illustrated Bible Dictionary: And Treasury of Biblical History, Biography, Geography, Doctrine and Literature'', T. Nelson, (London), 1893.

* Edmonston, W.E., ''The Induction of Hypnosis'', John Wiley & Sons, (New York), 1986. * Gauld, A., ''A History of Hypnotism'', Cambridge University Press, 199

* Gauld, A., "Braid, James (1795–1860)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 200

* * Hammond, D.C. (2013), "A Review of the History of Hypnosis Through the Late 19th Century", ''American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis'', Vol. 56, No. 2, (October 2013), pp. 174–81.

Harte, R., ''Hypnotism and the Doctors, Volume II: The Second Commission; Dupotet And Lafontaine; The English School; Braid's Hypnotism; Statuvolism; Pathetism; Electro-Biology'', L.N. Fowler & Co., (London), 1903

* * William S. Kroger, Kroger, W.S., ''Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis in Medicine, Dentistry, and Psychology (Revised Second Edition)'', Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, (Philadelphis), 2008. * Livingstone, D.

"Arsenic as a Remedy for the Tsetse Bite (Letter to the Editor, written at sea on 22 March 1858)", ''British Medical Journal'', Vol. 1, No. 70, (1 May 1858), pp. 360–61.

Noble, D., ''Elements of Psychological Medicine: An Introduction to the Practical Study of Insanity Adapted for Students and Junior Practitioners'', John Churchill, (London), 1853.

* Philips, J.P. (1860) seud. of Durand de Gros, J.P.br>''Cours Théorique et Pratique de Braidisme, ou Hypnotisme Nerveux, Considéré dans ses Rapports avec la Psychologie, la Physiologie et la la Pathologie, et dans ses Applications à la Médecine, à la Chirurgie, à la Physiologic Expérimentale, à la Médecine legale, et à l’Education. Par le Docteur J. P. Philips, suivi de la relation des expériences faites par le Professeur devant ses élèves, et de élèves, et de Nombreuses Observations par les Docteurs Azam, Braid, Broca, Carpenter, Cloquet, Demarquay, Esdaile, Gigot-Suard, Giraud-Teulon, Guérineau, Ronzier-Joly, Rostan, etc.''

("A Theoretical and Practical Course of Braidism, or Nervous Hypnotism considered in its various relations to Psychology, Physiology and Pathology, and in its Applications to Medicine, Surgery, Experimental Physiology, Forensic Science, and Education. By Doctor J.P. Philips, based on experiments conducted by the Professor in front of his pupils, and by his pupils, and the numerous observations by the Doctors Azam, Braid, Broca, Carpenter, Cloquet, Demarquay, Esdaile, Gigot-Suard, Giraud-Teulon, Guérineau, Ronzier-Joly, Rostan, etc."), J. B. Baillière et Fils, (Paris), 1860. * Simpson, J., "Letter from Mr. Simpson on Hypnotism, and Mr Braid's Theory of Phreno-Mesmeric Manifestations"

''The Phrenological Journal, and Magazine of Moral Science'', Vol. 17, No. 80, (July 1844), pp. 260–72.

Sutton, C.W., "Braid, James (1795?–1860)", pp. 198–99 in Lee, S. (ed), ''Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. VI: Bottomley-Browell'', Smith, Elder, & Co., (London), 1886.

* * * Weitzenhoffer A.M. (2000)

''The Practice of Hypnotism (Second Edition), New York: John Wiley and Sons.

* Weitzenhoffer A.M., Gough P.B., & Landes J. (1959), "A Study of the Braid Effect: (Hypnosis by Visual Fixation)", ''The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied'', Vol.47, No.1 (January 1959), pp.67–80.

Williamson, W.C. (Williamson, A.C., ed.), ''Reminiscences of a Yorkshire Naturalist'', George Redway, (London), 1896.

Yeates, L.B., ''James Braid: Surgeon, Gentleman Scientist, and Hypnotist'', Ph.D. Dissertation, School of History and Philosophy of Science, Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences, University of New South Wales, January 2013.

Yeates, L.B. (2018a), "James Braid (I): Natural Philosopher, Structured Thinker, Gentleman Scientist, and Innovative Surgeon", ''Australian Journal of Clinical Hypnotherapy & Hypnosis'', Vol. 40, No. 1, (Autumn 2018), pp. 3–39.

Yeates, L.B. (2018b), "James Braid (II): Mesmerism, Braid’s Crucial Experiment, and Braid’s Discovery of Neuro-Hypnotism", ''Australian Journal of Clinical Hypnotherapy & Hypnosis'', Vol. 40, No. 1, (Autumn 2018), pp. 40–42.

Yeates, L.B. (2018c), "James Braid (III): Braid’s Boundary-Work, M‘Neile’s Personal Attack, and Braid’s Defence", ''Australian Journal of Clinical Hypnotherapy and Hypnosis'', Vol. 40, No. 2, (Spring 2018), pp. 3–57.

Yeates, L.B. (2018d), "James Braid (IV): Braid’s Further Boundary-Work, and the Publication of ''Neurypnology''", ''Australian Journal of Clinical Hypnotherapy and Hypnosis'', Vol. 40, No. 2, (Spring 2018), pp. 58–111.

Yeates, L.B. (2018e), "James Braid (V): Chemical and Hypnotic Anaesthesia, Psycho-Physiology, and Braid’s Final Theories", ''Australian Journal of Clinical Hypnotherapy and Hypnosis'', Vol. 40, No. 2, (Spring 2018), pp. 112–67.

Yeates, L.B. (2018f), "James Braid (VI): Exhuming the Authentic Braid – Priority, Prestige, Status, and Significance", ''Australian Journal of Clinical Hypnotherapy and Hypnosis'', Vol. 40, No. 2, (Spring 2018), pp. 168–218.

James Braid Society

W3C's Markup Home Page

{{DEFAULTSORT:Braid, James Scottish hypnotists 1795 births 1860 deaths Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Scottish scientists Scottish surgeons People from Fife Scottish neurosurgeons Natural philosophers

surgeon

In modern medicine, a surgeon is a medical professional who performs surgery. Although there are different traditions in different times and places, a modern surgeon usually is also a licensed physician or received the same medical training as ...

, natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior throu ...

, and "gentleman scientist

An independent scientist (historically also known as gentleman scientist) is a financially independent scientist who pursues scientific study without direct affiliation to a public institution such as a university or government-run research and ...

".

He was a significant innovator in the treatment of clubfoot

Clubfoot is a birth defect where one or both feet are rotated inward and downward. Congenital clubfoot is the most common congenital malformation of the foot with an incidence of 1 per 1000 births. In approximately 50% of cases, clubfoot aff ...

, spinal curvature, knock-knees, bandy legs, and squint

Squinting is the action of looking at something with partially closed eyes.

Squinting is most often practiced by people who suffer from refractive errors of the eye who either do not have or are not using their glasses. Squinting helps momentari ...

; a significant pioneer of hypnotism and hypnotherapy

Hypnotherapy is a type of mind–body intervention in which hypnosis is used to create a state of focused attention and increased suggestibility in the treatment of a medical or psychological disorder or concern. Popularized by 17th and 18th cen ...

, and an important and influential pioneer in the adoption of both hypnotic anaesthesia and chemical anaesthesia. He is regarded by some, such as Kroger (2008, p. 3), as the "Father of Modern Hypnotism"; however, in relation to the issue of there being significant connections between Braid's "hypnotism" and "modern hypnotism" (as practised), let alone "identity", Weitzenhoffer (2000, p. 3) urges the utmost caution in making any such assumption:

Also, in relation to the clinical application of "hypnotism",

Early life

Braid was the third son, and the seventh and youngest child, of James Braid (c. 1761–184?) and Anne Suttie (c. 1761–?). He was born at Ryelaw House, in the Parish ofPortmoak

Portmoak is a parish in Kinross-shire, Scotland. It consists of a group of settlements running north to south: Glenlomond, Wester Balgedie, Easter Balgedie, Kinnesswood, Kilmagadwood and Scotlandwell.

The name derives from the Port of St Mo ...

, Kinross

Kinross (, gd, Ceann Rois) is a burgh in Perth and Kinross, Scotland, around south of Perth and around northwest of Edinburgh. It is the traditional county town of the historic county of Kinross-shire.

History

Kinross's origins are connect ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

on 19 June 1795.

On 17 November 1813, at the age of 18, Braid married Margaret Mason (1792–1869), aged 21, the daughter of Robert Mason (?–1813) and Helen Mason, née Smith. They had two children, both of whom were born at Leadhills

Leadhills, originally settled for the accommodation of miners, is a village in South Lanarkshire, Scotland, WSW of Elvanfoot. The population in 1901 was 835. It was originally known as Waterhead.

It is the second highest village in Scotland, ...

in Lanarkshire: Anne Daniel, née Braid (1820–1881), and James Braid (1822–1882).

Education

Braid was apprenticed to theLeith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by '' Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

surgeons Thomas and Charles Anderson (i.e., both father and son). As part of that apprenticeship, Braid also attended the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

from 1812 to 1814, where he was also influenced by Thomas Brown, M.D. (1778–1820), who held the chair of Moral Philosophy at Edinburgh from 1808 to 1820.

Braid obtained the diploma of the Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of the City of Edinburgh, the Lic.R.C.S. (Edin), in 1815, which entitled him to refer to himself as a member of the college (rather than a fellow).

Surgeon

Braid was appointed surgeon toLord Hopetoun

John Adrian Louis Hope, 1st Marquess of Linlithgow, 7th Earl of Hopetoun, (25 September 1860 – 29 February 1908) was a British aristocrat and statesman who served as the first governor-general of Australia, in office from 1901 to 1902. He wa ...

's mines at Leadhills

Leadhills, originally settled for the accommodation of miners, is a village in South Lanarkshire, Scotland, WSW of Elvanfoot. The population in 1901 was 835. It was originally known as Waterhead.

It is the second highest village in Scotland, ...

, Lanarkshire, in 1816. In 1825, he set up in private practice at Dumfries

Dumfries ( ; sco, Dumfries; from gd, Dùn Phris ) is a market town and former royal burgh within the Dumfries and Galloway council area of Scotland. It is located near the mouth of the River Nith into the Solway Firth about by road from the ...

, where he also "encountered the exceptional surgeon, William Maxwell, MD (1760–1834)".

One of his Dumfries' patients, Alexander Petty (1778–1864), a Scot, employed as a traveller for Scarr, Petty and Swain, a firm of Manchester tailors, invited Braid to move his practice to Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

, England. Braid moved to Manchester in 1828, continuing to practise from there until his death in 1860.

Braid was a well-respected, highly skilled, and very successful surgeon,

:" ndthough he was best known in the medical world for his theory and practice of hypnotism, he had also obtained wonderfully successful results by operation in cases of club foot

Clubfoot is a birth defect where one or both feet are rotated inward and downward. Congenital clubfoot is the most common congenital malformation of the foot with an incidence of 1 per 1000 births. In approximately 50% of cases, clubfoot aff ...

and other deformities, which brought him patients from every part of the kingdom

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

. Up to 1841 iz., when he first encountered hypnotismhe had operated on 262 cases of talipes, 700 cases of strabismus

Strabismus is a vision disorder in which the eyes do not properly align with each other when looking at an object. The eye that is focused on an object can alternate. The condition may be present occasionally or constantly. If present during a ...

, and 23 cases of spinal curvature."

Learned Society and Technical Institute Affiliations

Braid was a member of a number of prestigious "learned societies

A learned society (; also learned academy, scholarly society, or academic association) is an organization that exists to promote an academic discipline, profession, or a group of related disciplines such as the arts and science. Membership may ...

" and technical/educational institutions: a member of both the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd) is a professional organisation of surgeons. The College has seven active faculties, covering a broad spectrum of surgical, dental, and other medical practices. Its main campus is located on ...

and the Provincial Medical and Surgical Association

The Provincial Medical and Surgical Association (PMSA) was founded by Sir Charles Hastings on 19 July 1832 at a meeting in the Board Room of the Worcester Infirmary. It was initially established for the sharing of scientific and medical knowled ...

, a Corresponding Member of both the Wernerian Natural History Society of Edinburgh

The Wernerian Natural History Society (12 January 1808 – 16 April 1858), commonly abbreviated as the Wernerian Society, was a learned society interested in the broad field of natural history, and saw papers presented on various topics such as ...

(in 1824), and the Royal Medical Society of Edinburghin 1854

, a Member of the Manchester Athenæum, and the Honorary Curator of the museum of the Manchester Natural History Society.

Mesmerism

Braid first observed the operation ofanimal magnetism

Animal magnetism, also known as mesmerism, was a protoscientific theory developed by German doctor Franz Mesmer in the 18th century in relation to what he claimed to be an invisible natural force (''Lebensmagnetismus'') possessed by all livi ...

, when he attended a public performance by the travelling French magnetic demonstrator Charles Lafontaine

Charles Léonard Lafontaine (27 March 1803 – 13 August 1892) was a celebrated French " public magnetic demonstrator", who also "had an interest in animal magnetism as an agent for curing or alleviating illnesses".

Family

Charles Lafontaine ...

(1803–1892) at the '' Manchester Athenæum'' on Saturday, 13 November 1841.

In ''Neurypnology'' (1843, pp. 34–35) he states that, prior to his encounter with Lafontaine, he had already been totally convinced by a four-part investigation of Animal Magnetism published in ''The London Medical Gazette'' (i.e., Anon, 1838) that there was no evidence of the existence of any magnetic agency for any such phenomena. The final article's last paragraph read:

::This, then, n conclusion,is our case. Every credible effect of magnetism has occurred, and every incredible is said to have occurred, in cases where no magnetic influence has been exerted, but in all which, excited imagination, irritation, or some powerful mental impression, has operated: where the mind has been alone acted on, magnetic effects have been produced without magnetic manipulations: where magnetic manipulations have been employed, unknown, and therefore without the assistance of the mind, no result has ever been produced. Why, then, imagine a new agent, which cannot act by itself, and which has never yet even seemed to produce a new phenomenon?

And, along with the strong impression made upon Braid by the ''Medical Gazette's'' article, there was also the more recent impressions made by Thomas Wakley

Thomas Wakley (11 July 179516 May 1862) was an English surgeon. He gained fame as a social reformer who campaigned against incompetence, privilege and nepotism. He was the founding editor of ''The Lancet'', a radical Member of Parliament (MP) a ...

's exposure of the comprehensive fraud of John Elliotson's subjects, the Okey sisters,

:: ll of whichdetermined me to consider the whole as a system of collusion or illusion, or of excited imagination, sympathy, or imitation. ''I therefore abandoned the subject as unworthy of farther investigation, until I attended the conversazioni of Lafontaine'', where I saw one fact, the inability of a patient to open his eyelids, which arrested my attention; I felt convinced it was not to be attributed to any of the causes referred to, and I therefore instituted experiments to determine the question; and exhibited the results to the public in a few days after. – (Braid, ''Neurypnology'' (1843), p. 35; emphasis added).

Braid always maintained that he had gone to Lafontaine's demonstration as an open-minded sceptic, eager to examine the presented evidence at first hand – that is, rather than "entirely ependingon reading or hearsay evidence for his knowledge of it" – and, then, from that evidence, form a considered opinion of Lafontaine's work. He was neither a closed-minded cynic intent on destroying Lafontaine, nor a deluded and naïvely credulous believer seeking authorization of his already formed belief.

Braid was amongst the medical men who were invited onto the platform by Lafontaine. Braid examined the physical condition of Lafontaine's magnetised subjects (especially their eyes and their eyelids) and concluded that they were, indeed, in quite a different physical state. Braid always stressed the significance of attending Lafontaine's ''conversazione

A ''conversazione'' is a "social gathering redominantlyheld by learned or art society" for conversation and discussion, especially about the arts, literature, medicine, and science.

::It would not be easy to devise a happier way han the ''con ...

''.

Hypnotism

Lafontaine

Braid attended two more of Lafontaine's demonstrations; and, by the third demonstration (on Saturday 20 November 1841), Braid was convinced of the veracity of some of Lafontaine's effects and phenomena (see Yeates, 2018b, pp. 56–63). In particular, whilst Braid was entirely convinced that a transformation from, so to speak, condition1 to condition2, and back to condition1 had really taken place, he was also entirely convinced that no ''magnetic agency'' of any sort (as Lafontaine emphatically claimed) was responsible for the (veridical) events he had witnessed at first hand. He also rejected outright the assertion that the transformation in question had "proceeded from, orad been

Advertising is the practice and techniques employed to bring attention to a product or service. Advertising aims to put a product or service in the spotlight in hopes of drawing it attention from consumers. It is typically used to promote a ...

excited into action by another erson (''Neurypnology'', p. 32).

Braid's ''experimentum crucis''

Braid then performed his own ''experimentum crucis

In science, an ''experimentum crucis'' (English: crucial experiment or critical experiment) is an experiment capable of decisively determining whether or not a particular hypothesis or theory is superior to all other hypotheses or theories whose ...

''. Operating on the principle of Occam's Razor

Occam's razor, Ockham's razor, or Ocham's razor ( la, novacula Occami), also known as the principle of parsimony or the law of parsimony ( la, lex parsimoniae), is the problem-solving principle that "entities should not be multiplied beyond neces ...

(that 'entities ought not to be multiplied beyond necessity'), and recognising that he could diminish, rather than multiply entities, he made an extraordinary decision to perform a role-reversal and treat the operator-subject interaction as subject-internal, operator-guided procedure; rather than, as Lafontaine supposed, an operator-centred, subject-external procedure. Braid emphatically proved his point by his self-experimentation

Self-experimentation refers to the special case of single-subject research in which the experimenter conducts the experiment on themselves.

Usually this means that a single person is the designer, operator, subject, analyst, and user or reporte ...

with his "upwards and inwards squint".

The exceptional success of Braid's use of 'self-' or 'auto-hypnotism' (rather than 'hetero-hypnotism'), entirely by himself, on himself, and within his own home, clearly demonstrated that it had nothing whatsoever to do with the 'gaze', 'charisma', or 'magnetism' of the operator; all it needed was a subject's 'fixity of vision' on an 'object of concentration' at such a height and such a distance from the bridge of their nose that the desired 'upwards and inwards squint' was achieved. And, at the same time, by using himself as a subject, Braid also conclusively proved that none of Lafontaine's phenomena were due to magnetic agency.

"Auto-hypnotization" and "hetero-hypnotization"

Braid conducted a number of experiments with self-hypnotization upon himself, and, by now convinced that he had discovered the natural psycho-physiological mechanism underlying these quite genuine effects, he performed his first act of hetero-hypnotization at his own residence, before several witnesses, including Captain Thomas Brown (1785–1862) on Monday 22 November 1841 – his first hypnotic subject was Mr. J. A. Walker.see ''Neurypnology'', pp. 16–20.

Absence of physical contact

The following Saturday, (27 November 1841) Braid delivered his first public lecture at the Manchester Athenæum, in which, amongst other things, he was able to demonstrate that he could replicate the effects produced by Lafontaine, without the need for any sort of physical contact between the operator and the subject.Hugh M‘Neile's "Satanic Agency and Mesmerism" sermon

On the evening of Sunday, 10 April 1842, at St Jude's Church, Liverpool, the controversial cleric

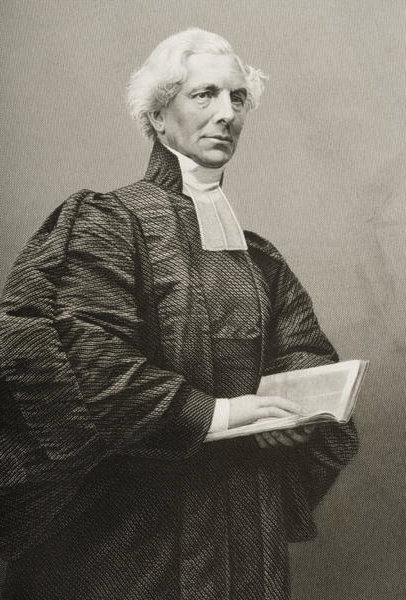

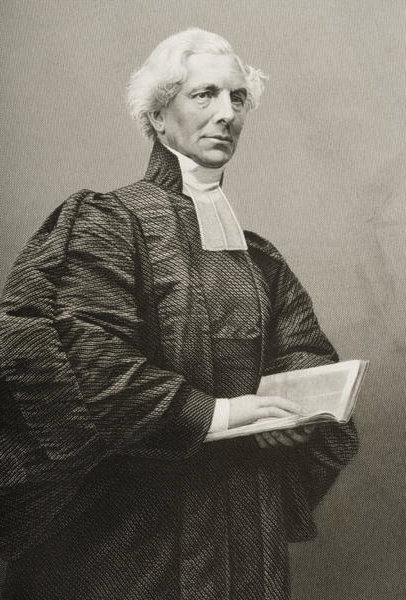

On the evening of Sunday, 10 April 1842, at St Jude's Church, Liverpool, the controversial cleric Hugh Boyd M‘Neile

Hugh Boyd M‘Neile (18 July 1795 – 28 January 1879) was a well-connected and controversial Irish-born Calvinist Anglican of Scottish descent.

Fiercely anti- Tractarian and anti-Roman Catholic (and, even more so, anti-Anglo-Catholic) and an ...

preached a sermon against Mesmerism for more than ninety minutes to a capacity congregation; and, according to most critics, it was a poorly argued and unimpressive performance.

M'Neile's core argument was that scripture asserts the existence of "satanic agency"; and, in the process of delivering his sermon, he provided examples of the various instantiations that "satanic agency" might manifest (observing times, divination

Divination (from Latin ''divinare'', 'to foresee, to foretell, to predict, to prophesy') is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout histor ...

, necromancy

Necromancy () is the practice of magic or black magic involving communication with the dead by summoning their spirits as apparitions or visions, or by resurrection for the purpose of divination; imparting the means to foretell future events; ...

, etc.), and claimed that these were all forms of "witchcraft"; and, further, he asserted that, because scripture asserts that, as "latter times" approach, more and more evidence of "satanic agency" will appear, it was, M‘Neile asserted, ''ipso facto

is a Latin phrase, directly translated as "by the fact itself", which means that a specific phenomenon is a ''direct'' consequence, a resultant ''effect'', of the action in question, instead of being brought about by a previous action. It is a ...

'', transparently obvious that the exhibitions of Lafontaine and Braid, in Liverpool, at that very moment, were concrete examples of those particular instantiations.

He then moved into a confusing admixture of philippic A philippic ()http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/English/philippic is a fiery, damning speech, or tirade, delivered to condemn a particular political actor. The term is most famously associated with two noted orators of the ancient world: ...

(against Braid and Lafontaine), and polemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topics ...

(against animal magnetism), wherein he concluded that all mesmeric phenomena were due to "satanic agency". In particular, he attacked Braid as a man, a scientist, a philosopher, and a medical professional. He claimed that Braid and Lafontaine were one and the same kind. He also threatened Braid's professional and social position by associating him with Satan; and, in the most ill-informed way, condemned Braid's important therapeutic work as having no clinical efficacy whatsoever.

The sermon was reported on at some length in the ''Liverpool Standard'', two days later. Once Braid became fully aware of the newspaper reports of the conglomeration of matters that were reportedly raised in M‘Neile's sermon, and the misrepresentations and outright errors of fact that it allegedly contained, as well as the vicious nature of the insults, and the implicit and explicit threats which were levelled against Braid's own personal, spiritual, and professional well-being by M‘Neile, he sent a detailed private letter to M‘Neile accompanied by a newspaper account of a lecture he had delivered on the preceding Wednesday evening (13 April) at Macclesfield, and a cordial invitation (plus a free admission ticket) for M‘Neile to attend Braid's Liverpool lecture, on Thursday, 21 April.

Yet, despite Braid's courtesy, in raising his deeply felt concerns directly to M‘Neile, in private correspondence, M‘Neile did not acknowledge Braid's letter nor did he attend Braid's lecture. Further, in the face of all the evidence Braid had presented, and seemingly, ''without the slightest correction of its original contents'', M‘Neile allowed the entire text of his original sermon, as it had been transcribed by a stenographer (more than 7,500 words), to be published on Wednesday, 4 May 1842. It was this 'most ungentlemanly' act of M‘Neile towards Braid, that forced Braid to publish his own response as a pamphlet; which he did on Saturday, 4 June 1842; a pamphlet which, in Crabtree's opinion is "a work of the greatest significance in the history of hypnotism, and of utmost rarity" (1988, p. 121).

British Association for the Advancement of Science

Soon after, he also wrote a report entitled "Practical Essay on the Curative Agency of Neuro-Hypnotism", which he applied to have read before theBritish Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chie ...

in June 1842. Despite being initially accepted for presentation, the paper was controversially rejected at the last moment; but Braid arranged for a series of Conversazione

A ''conversazione'' is a "social gathering redominantlyheld by learned or art society" for conversation and discussion, especially about the arts, literature, medicine, and science.

::It would not be easy to devise a happier way han the ''con ...

at which he presented its contents. Braid summarised and contrasted his own view with the other views prevailing at that time: ::"The various theories at present entertained regarding the phenomena of mesmerism may be arranged thus: First, those who believe them to be owing entirely to a system of collusion and delusion; and a great majority of society may be ranked under this head. Second, those who believe them to be real phenomena, but produced solely by imagination, sympathy, and imitation. Third, the animal magnetists, or those who believe in some magnetic medium set in motion as the exciting cause of the mesmeric phenomena. Fourth, those who have adopted my views, that the phenomena are solely attributable to a peculiar physiological state of the brain and the spinal cord."

Terminology

By, at least, 28 February 1842, Braid was using "Neurohypnology" (which he later shortened to "Neurypnology"); and, in a public lecture on Saturday, 12 March 1842, at the Manchester Athenæum, Braid explained his terminological developments as follows:

::I therefore think it desirable to assume another name han animal magnetismfor the phenomena, and have adopted neurohypnology – a word which will at once convey to every one at all acquainted with Greek, that it is the rationale or doctrine of nervous sleep; sleep being the most constant attendant and natural analogy to the primary phenomena of mesmerism; the prefix "nervous" distinguishing it from natural sleep. There are only two other words I propose by way of innovation, and those are hypnotism for magnetism and mesmerism, and hypnotised for magnetised and mesmerised.

It is important to recognize three things; namely, that:

:(1) Braid was only using the term "sleep" metaphorically;

:(2) despite the constant mistaken assertions in the modern literature, Braid did not, even on a single occasion, ever use the term hypnosis; and

:(3) the term 'hypnosis' comes from the work of the Nancy School in the 1880s.

Although Braid was the first to use the terms '' hypnotism'', ''

By, at least, 28 February 1842, Braid was using "Neurohypnology" (which he later shortened to "Neurypnology"); and, in a public lecture on Saturday, 12 March 1842, at the Manchester Athenæum, Braid explained his terminological developments as follows:

::I therefore think it desirable to assume another name han animal magnetismfor the phenomena, and have adopted neurohypnology – a word which will at once convey to every one at all acquainted with Greek, that it is the rationale or doctrine of nervous sleep; sleep being the most constant attendant and natural analogy to the primary phenomena of mesmerism; the prefix "nervous" distinguishing it from natural sleep. There are only two other words I propose by way of innovation, and those are hypnotism for magnetism and mesmerism, and hypnotised for magnetised and mesmerised.

It is important to recognize three things; namely, that:

:(1) Braid was only using the term "sleep" metaphorically;

:(2) despite the constant mistaken assertions in the modern literature, Braid did not, even on a single occasion, ever use the term hypnosis; and

:(3) the term 'hypnosis' comes from the work of the Nancy School in the 1880s.

Although Braid was the first to use the terms '' hypnotism'', ''hypnotise

Hypnosis is a human condition involving focused attention (the selective attention/selective inattention hypothesis, SASI), reduced peripheral awareness, and an enhanced capacity to respond to suggestion.In 2015, the American Psychologica ...

'' and '' hypnotist'' in English, the cognate

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words in different languages that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymology, etymological ancestor in a proto-language, common parent language. Because language c ...

terms ''hypnotique'', ''hypnotisme'', ''hypnotiste'' had been intentionally used by the French magnetist Baron Etienne Félix d'Henin de Cuvillers (1755–1841) at least as early as 1820. Braid, moreover, was the first person to use "hypnotism" in its modern sense, referring to a "psycho-physiological" theory rather than the "occult" theories of the magnetists.

In a letter written to the editor of The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal and one of the oldest of its kind. It is also the world's highest-impact academic journal. It was founded in England in 1823.

The journal publishes original research articles, ...

in 1845, Braid emphatically states that:

:"I adopted the term "hypnotism" to prevent my being confounded with those who entertain those extreme notions c. that a mesmeriser's ''will'' has an "irresistible power… over his subjects" and that clairvoyance and other "higher phenomena" are routinely manifested by those in the mesmeric state], as well as to get rid of the erroneous theory about a magnetic fluid, or exoteric influence of any description being the cause of the sleep. I distinctly avowed that hypnotism laid no claim to produce any phenomena which were not "quite reconcilable with well-established physiological and psychological principles"; pointed out the various sources of fallacy which might have misled the mesmerists; ndwas the first to give a public explanation of the trick y which a fraudulent subject had been able to deceive his mesmeriser��

: urther, I have never beena supporter of the imagination theory – i.e., that the induction of ypnosisin the first instance is merely the result of imagination. My belief is quite the contrary. I attribute it to the induction of a habit of intense abstraction, or concentration of attention, and maintain that it is most readily induced by causing the patient to fix his thoughts and sight on an object, and suppress his respiration."

Induction

In his first publication (i.e., ''Satanic Agency and Mesmerism Reviewed'', etc.), he had also stressed the importance of the subject concentrating both vision and thought, referring to "the continued fixation of the mental and visual eye" The concept of the mind's eye first appeared in English in Chaucer'sMan of Law's Tale

"The Man of Law's Tale" is the fifth of the ''Canterbury Tales'' by Geoffrey Chaucer, written around 1387. John Gower's "Tale of Constance" in ''Confessio Amantis'' tells the same story and may have been a source for Chaucer. Nicholas Trivet's ...

in his Canterbury Tales

''The Canterbury Tales'' ( enm, Tales of Caunterbury) is a collection of twenty-four stories that runs to over 17,000 lines written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 and 1400. It is widely regarded as Chaucer's ''magnum opus' ...

, where he speaks of a man "who was blind, and could only see with the eyes of his mind, with which all men see after they go blind". as a means of engaging a natural physiological mechanism that was already ''hard-wired'' into each human being:

:"I shall merely add, that my experiments go to prove that it is a law in the animal economy that, by the continued fixation of the mental and visual eye on any object in itself not of an exciting nature, with absolute repose of body and general quietude, they become wearied; and, provided the patients rather favour than resist the feeling of stupor which they feel creeping over them during such experiment, a state of somnolency is induced, and that peculiar state of brain, and mobility of the nervous system, which render the patient liable to be directed so as to manifest the mesmeric phenomena. I consider it not so much the optic, as the motor and sympathetic nerves, and the mind, through which the impression is made. Such is the position I assume; and I feel so thoroughly convinced that it is a law of the animal economy, that such effects should follow such condition of mind and body, that I fear not to state, as my deliberate opinion, that this is a fact which cannot be controverted."

In 1843 he published ''Neurypnology; or the Rationale of Nervous Sleep'' ''Considered in Relation with Animal Magnetism...'', his first and only book-length exposition of his views. According to Bramwell, the work was popular from the outset, selling 800 copies within a few months of its publication.

Braid thought of hypnotism as producing a "nervous sleep" which differed from ordinary sleep. The most efficient way to produce it was through visual fixation on a small bright object held eighteen inches above and in front of the eyes. Braid regarded the physiological condition underlying hypnotism to be the over-exercising of the eye muscles through the straining of attention.

He completely rejected

In 1843 he published ''Neurypnology; or the Rationale of Nervous Sleep'' ''Considered in Relation with Animal Magnetism...'', his first and only book-length exposition of his views. According to Bramwell, the work was popular from the outset, selling 800 copies within a few months of its publication.

Braid thought of hypnotism as producing a "nervous sleep" which differed from ordinary sleep. The most efficient way to produce it was through visual fixation on a small bright object held eighteen inches above and in front of the eyes. Braid regarded the physiological condition underlying hypnotism to be the over-exercising of the eye muscles through the straining of attention.

He completely rejected Franz Mesmer

Franz Anton Mesmer (; ; 23 May 1734 – 5 March 1815) was a German physician with an interest in astronomy. He theorised the existence of a natural energy transference occurring between all animated and inanimate objects; this he called " ani ...

's idea that a magnetic

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that are mediated by a magnetic field, which refers to the capacity to induce attractive and repulsive phenomena in other entities. Electric currents and the magnetic moments of elementary particle ...

fluid caused hypnotic phenomena, because anyone could produce them in "himself by attending strictly to the simple rules" that he had laid down. The (derogative) suggestion that ''Braidism'' be adopted as a synonym for "hypnotism" was rejected by Braid; and it was rarely used at the time of the suggestion, and is never used today.

Braid’s "sources of fallacy"

Nearly a year after the publication of ''Neurypnology'', the secretary of theRoyal Manchester Institution

The Royal Manchester Institution (RMI) was an England, English learned society founded on 1 October 1823 at a public meeting held in the Exchange Room by Manchester merchants, local artists and others keen to dispel the image of Manchester as a ...

invited Braid to conduct a conversazione in the Institution's lecture theatre on Monday, 22 April 1844.

Braid spoke at considerable length to a very large audience on hypnotism; and also gave details of the important differences he had identified between his "hypnotism" and mesmerism/animal magnetism. According to the extensive press reports, "the interest felt by the members of the institution in the subject was manifested by the attendance of one of the largest audiences we ever recollect to have seen present".

In 1903, Bramwell published a list of eight "sources of fallacy" attributed to Braid; the final two having been directly paraphrased, by Bramwell, from other aspects of Braid's later works (see text at right).

In 1853, Braid investigated the phenomenon of "table-turning

Table-turning (also known as table-tapping, table-tipping or table-tilting) is a type of séance in which participants sit around a table, place their hands on it, and wait for rotations. The table was purportedly made to serve as a means of comm ...

" and clearly confirmed Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

's conclusion that the phenomenon was entirely due to the ideo-motor influences of the participants, rather than to the agency of "mesmeric forces" – as was being widely asserted by, for example, John Elliotson

John Elliotson (29 October 1791 – 29 July 1868), M.D. (Edinburgh, 1810), M.D.(Oxford, 1821), F.R.C.P.(London, 1822), F.R.S. (1829), professor of the principles and practice of medicine at University College London (1832), senior physician to ...

and his followers.

The mono-ideo-dynamic principle

On 12 March 1852, convinced (as both a scientist and physiologist) of the genuineness of Braid's ''hypnotism'', Braid's friend and colleagueWilliam Benjamin Carpenter

William Benjamin Carpenter CB FRS (29 October 1813 – 19 November 1885) was an English physician, invertebrate zoologist and physiologist. He was instrumental in the early stages of the unified University of London.

Life

Carpenter was born ...

presented a significant paper, "On the influence of Suggestion in Modifying and directing Muscular Movement, independently of Volition", to the Royal Institution of Great Britain

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

(it was published later that year).

Carpenter explained that the "class of phenomena" associated with Braid's hypnotism were consequent upon a subject's concentration on a single, "dominant idea": namely, "the occupation of the mind by the ''ideas'' which have been suggested to it, and in the influence which these ideas exert upon the actions of the body". Moreover, Carpenter said, "it is not really the ''will'' of the operator which controls the ''sensations'' of the subject; but the ''suggestion'' of the operator which excites a corresponding ''idea''": the suggested ''idea'' "not only roducing non-volitionalmuscular movements hrough this psychosomatic mechanism but other bodily changes s well (1852, p. 148).

In order to reconcile the observed hypnotic phenomena "with the known laws of nervous action" (p. 153), and without elaborating on mechanism, Carpenter identified a new psycho-physiological reflex activity – in addition to the already identified ''excito''-motor (which was responsible for breathing, swallowing, etc.), and the ''sensori''-motor (which was responsible for startle responses, etc.) – that of "the ''ideo''-motor principle of action". At the conclusion of his paper, Carpenter briefly noted that his proposed ''ideo-motor principle of action'', specifically created to explain Braid's ''hypnotism'', could also explain other activities involving objectively psychosomatic responses, such as the movements of divining rods:

Braid immediately adopted Carpenter's ideo-motor terminology; and, in order to stress the importance (within Braid's own representation) of the single, "dominant" idea concept, Braid spoke of a "''mono-ideo-motor'' principle of action". However, by 1855, based on suggestions that had been made to Carpenter by Daniel Noble, their friend in common – that Carpenter's innovation would be more accurately understood, and more accurately applied (viz., not just limited to divining rods and pendulums), if it were designated the "ideo-dynamic principle" – Braid was referring to a "''mono-ideo-dynamic'' principle of action":

Death

Braid maintained an active interest in hypnotism until his death. Just three days before his death he sent a (now lost) manuscript, that was written in English – usually referred to as ''On hypnotism'' – to the French surgeonÉtienne Eugène Azam

Étienne Eugène Azam (28 May 1822 – 16 December 1899), full name Charles-Marie-Étienne-Eugène Azam, was a French surgeon from Bordeaux who is chiefly remembered for his work in psychology, particularly a case involving a female patient he na ...

.

Braid died on 25 March 1860, in Manchester, after just a few hours of illness. According to some contemporary accounts he died from "apoplexy

Apoplexy () is rupture of an internal organ and the accompanying symptoms. The term formerly referred to what is now called a stroke. Nowadays, health care professionals do not use the term, but instead specify the anatomic location of the bleedi ...

", and according to others he died from "heart disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels. CVD includes coronary artery diseases (CAD) such as angina and myocardial infarction (commonly known as a heart attack). Other CVDs include stroke, hea ...

". He was survived by his wife, his son James (a general practitioner, rather than a surgeon), and his daughter.

Influence

Braid's work had a strong influence on a number of important French medical figures, especiallyÉtienne Eugène Azam

Étienne Eugène Azam (28 May 1822 – 16 December 1899), full name Charles-Marie-Étienne-Eugène Azam, was a French surgeon from Bordeaux who is chiefly remembered for his work in psychology, particularly a case involving a female patient he na ...

(1822–1899) of Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectur ...

(Braid's principal French "disciple"), the anatomist Pierre Paul Broca

Pierre Paul Broca (, also , , ; 28 June 1824 – 9 July 1880) was a French physician, anatomist and anthropologist. He is best known for his research on Broca's area, a region of the frontal lobe that is named after him. Broca's area is involve ...

(1824–1880), the physiologist Joseph Pierre Durand de Gros (1826–1901), and the eminent hypnotherapist and co-founder of the Nancy School

The Nancy School was a French hypnosis-centered school of psychotherapy. The origins of the thoughts were brought about by Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault in 1866, in Nancy, France. Through his publications and therapy sessions he was able to gain th ...

Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault

Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault (1823–1904) was a French physician and is considered the father of modern hypnotherapy. Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault was born in Favières, a small town in the Lorraine region of France, on September 16, 1823. He compl ...

(1823–1904).

Braid hypnotised the English Swedenborgian writer J.J.G. Wilkinson, who observed him hypnotising others several times, and began using hypnotism himself. Wilkinson soon became a passionate advocate of Braid's work and his published remarks on hypnotism were quoted enthusiastically by Braid several times in his later writings. However, Braid's legacy was maintained in Great Britain largely by John Milne Bramwell who collected all of his available works and published a biography and account of Braid's theory and practice as well as several books on hypnotism of his own (see below).

Works

Braid published many letters and articles in journals and newspapers; he also published several pamphlets, and a number of books (many of which were compendiums of his previously published works). His first major publication was ''Neurypnology, or the Rationale of Nervous Sleep'' (1843), written less than two years after his discovery of hypnotism. He continued revising his theories and his clinical applications of hypnotism, based on his experiments and his empirical experience. Six weeks before his death, in a letter to ''The Medical Circular'', Braid spoke of continuously having the daily experience of applying hypnotism in his practice for nineteen years; and, in a letter to ''The Critic'', written four weeks before his death (this was his last published letter), he spoke of how his experiments and clinical experience had convinced him that all of the effects of hypnotism were generated "by influences residing entirely ''within'', and ''not without'', the patient's own body". In 1851 Garth Wilkinson published a description of Braid's "hypnotism", which Braid described, two years later, as "a beautiful description of y system ofhypnotism". In April 2009, Robertson published a reconstructed English version, backward translated from the French, of Braid's last (lost) manuscript, ''On Hypnotism'', addressed by Braid to the French Academy of Sciences.Bramwell: promoter and defender of Braid's heritage

John Milne Bramwell, M.B. C.M., a talented specialist medical hypnotist and hypnotherapist himself, made a deep study of Braid's works and helped to revive and maintain Braid's legacy in Great Britain.

Bramwell had studied medicine at Edinburgh University in the same student cohort as Braid's grandson, Charles.

Consequently, due to his Edinburgh studies – especially those with John Hughes Bennett (1812–1875), author of ''The Mesmeric Mania of 1851, With a Physiological Explanation of the Phenomena Produced'' (1851) – Bramwell was very familiar with Braid and his work; and, more significantly, through Charles Braid, he also had unfettered access to those publications, records, papers, etc. of Braid that were still held by the Braid family. He was, perhaps, second only to

John Milne Bramwell, M.B. C.M., a talented specialist medical hypnotist and hypnotherapist himself, made a deep study of Braid's works and helped to revive and maintain Braid's legacy in Great Britain.

Bramwell had studied medicine at Edinburgh University in the same student cohort as Braid's grandson, Charles.

Consequently, due to his Edinburgh studies – especially those with John Hughes Bennett (1812–1875), author of ''The Mesmeric Mania of 1851, With a Physiological Explanation of the Phenomena Produced'' (1851) – Bramwell was very familiar with Braid and his work; and, more significantly, through Charles Braid, he also had unfettered access to those publications, records, papers, etc. of Braid that were still held by the Braid family. He was, perhaps, second only to Preyer Preyer is a surname. Notable people with this surname include:

* Carl Adolph Preyer (1863–1947), German-American pianist, composer, and teacher

* Gottfried von Preyer (1807–1901), Austrian composer, conductor, and teacher

* Johann Wilhelm Pr ...

in his wide-ranging familiarity with Braid and his works.

In 1896 Bramwell noted that, " raid’s nameis familiar to all students of hypnotism and is rarely mentioned by them without due credit being given to the important part he played in rescuing that science from ignorance and superstition". He found that almost all of those students believed that Braid "held many erroneous views" and that "the researches of more recent investigators addisproved hose erroneous views.

Finding that "few seem to be acquainted with any of raid'sworks except ''Neurypnology'' or with the fact that 'Neurypnology''was only one of a long series on the subject of hypnotism, and that in the later ones his views completely changed", Bramwell was convinced that this ignorance of Braid, which sprang from "imperfect knowledge of his writings", was further compounded by at least three "universally adopted opinions"; viz., that Braid was English (Braid was a Scot), "believed in phrenology

Phrenology () is a pseudoscience which involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.Wihe, J. V. (2002). "Science and Pseudoscience: A Primer in Critical Thinking." In ''Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience'', pp. 195–203. C ...

" (Braid did not), and "knew nothing of suggestion" (when, in fact, Braid was its strongest advocate, and, also, was first to apply the term "suggestion" to the practice).

Bramwell rejected the mistaken view – very widely promoted by Hippolyte Bernheim – that Braid knew nothing of suggestion, and that the entire 'history' of suggestive therapeutics began with the Nancy "Suggestion" School in the late 1880s, had no foundation whatsoever:

In 1897, Bramwell wrote on Braid's work for an important French hypnotism journal ("''James Braid: son œuvre et ses écrits''"). He also wrote on hypnotism and suggestion, strongly emphasizing the importance of Braid and his work ("''La Valeur Therapeutique de l'Hypnotisme et de la Suggestion''"). In his response, Bernheim repeated his entirely mistaken view that Braid knew nothing of suggestion ("''"A propos de l'étude sur James Braid par le Dr. Milne Bramwell, etc.''").

Bramwell's response ("''James Braid et la Suggestion, etc.''") to Bernheim's misrepresentation was emphatic:

::"I answered ernheim giving quotations from Braid's published works, which clearly showed that he not only employed suggestion as intelligently as the members of the Nancy school now do, but also that his conception of its nature was clearer than theirs" (''Hypnotism, etc.'' (1913), p. 28).In 1896, Bramwell spoke of perusing the collection of "800 works by nearly 500 authors", listed in Dessoir's ''Bibliographie des Modernen Hypnotismus'' Bibliography of Modern Hypnotism'(1888), and finding that "little of value has been discovered y any of themwhich can justly be considered as supplementary to Braid's later work" and that "much has been lost through heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Officiall ...

ignorance of his researches" ("On the Evolution of Hypnotic Theory" (1896), p. 459). Moreover, Bramwell found "the Nancy theories f "Bernheim and his colleagues" inthemselves are but an imperfect reproduction of Braid's later ones" ("On the Evolution of Hypnotic Theory", p. 459). In 1913, Bramwell expressed the same opinion of Dessoir's later (1890) collection of 1182 works by 774 authors (''Hypnotism, etc.'' (1913), pp. 274–75).

James Braid Society

In 1997 Braid's part in developing hypnosis for therapeutic purposes was recognised and commemorated by the creation of the James Braid Society, a discussion group for those "involved or concerned in the ethical uses of hypnosis". The society meets once a month in central London, usually for a presentation on some aspect of hypnotherapy.Footnotes

Sources

Braid's publications (in chronological order)

Braid, J., ''Satanic Agency and Mesmerism Reviewed, In A Letter to the Reverend H. Mc. Neile, A.M., of Liverpool, in Reply to a Sermon Preached by Him in St. Jude's Church, Liverpool, on Sunday, 10 April 1842, by James Braid, Surgeon, Manchester'', Simms and Dinham, and Galt and Anderson, (Manchester), 1842.

**A transcription of the text of Braid's pamphlet is presented at Volgyesi, (Winter 1955), "Discovery of Medical Hypnotism: Part 2"; Volgyesi's transcription is reprinted at Robertson (''Discovery of Hypnosis''), pp. 375–81. Another transcription is presented at Tinterow (''Foundations of Hypnosis''), pp. 317–30.

Both of these transcriptions have errors; a complete transcription, corrected with direct reference to an original copy of Braid's pamphlet, and annotated for the modern reader is a

Yeates (2013)

pp. 671–700.

N.B. Braid intended that his pamphlet was to be read in association with the newspaper report in the ''Macclesfield Courier'' of Saturday, 16 April 1842. A complete transcription of the newspaper article, annotated for the modern reader is at Yeates (2013), pp. 599–620.

Braid, J., ''Neurypnology or the Rationale of Nervous Sleep Considered in Relation with Animal Magnetism Illustrated by Numerous Cases of its Successful Application in the Relief and Cure of Disease'', John Churchill, (London), 1843.

**N.B. Braid's ''Errata'', detailing a number of important corrections that need to be made to the foregoing text, is o

the un-numbered page following p. 265.

Braid, J., "Observations on the Phenomena of Phreno-Mesmerism", ''The Medical Times'', Vol. 9, No. 216, (11 November 1843), pp. 74–75

reprinted a

''The Phrenological Journal, and Magazine of Moral Science'', Vol. 17, No. 78, (January 1844), pp. 18–26.

* Braid, J., "Observations on Mesmeric and Hypnotic Phenomena"

''The Medical Times'', Vol. 10, No. 238, (13 April 1844), pp. 31–32

Braid, J., "The Effect of Garlic on the Magnetic Needle", ''The Medical Times'', Vol. 10, No. 241, (4 May 1844), pp. 98–99.

* Braid, J., "Physiological Explanation of Some Mesmeric Phenomena"

''The Medical Times'', Vol. 10, No. 258, (31 August 1844), pp. 450–51

reprinted a

"Remarks on Mr. Simpson’s Letter on Hypnotism, published in the Phrenological Journal for July 1844", ''The Phrenological Journal, and Magazine of Moral Science'', Vol. 17, No. 81, (October 1844), pp. 359–65.

Braid, J., "Experimental Inquiry, to Determine whether Hypnotic and Mesmeric Manifestations can be Adduced in Proof of Phrenology", ''The Medical Times'', Vol. 11, No. 271, (30 November 1844), pp. 181–82.

* Braid, J. "Magic, Mesmerism, Hypnotism, etc., Historically and Physiologically Considered"

''Medical Times'', Vol. 11, No. 272, (7 December 1844), pp. 203–04

Braid, J., "Experimental Inquiry to determine whether Hypnotic and Mesmeric Manifestations can be adduced in proof of Phrenology. By James Braid, M.R.C.S.E., Manchester. (From the ''Medical Times'', No. 271, 30 November 1844)", ''The Phrenological Journal, and Magazine of Moral Science'', Vol. 18, No. 83, (1845), pp. 156–62.