James A. Van Allen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Alfred Van Allen (September 7, 1914August 9, 2006) was an American space scientist at the

Van Allen was born on 7 September 1914 on a small farm near Mount Pleasant, Iowa. As a child, he was fascinated by mechanical and electrical devices and was an avid reader of ''

Van Allen was born on 7 September 1914 on a small farm near Mount Pleasant, Iowa. As a child, he was fascinated by mechanical and electrical devices and was an avid reader of ''

As ''Time'' magazine later reported, "Van Allen’s ‘

As ''Time'' magazine later reported, "Van Allen’s ‘

In 1955, the U.S. announced Project Vanguard as part of the US contribution to the

In 1955, the U.S. announced Project Vanguard as part of the US contribution to the  * January 31, 1958: The first American satellite,

* January 31, 1958: The first American satellite,

* Elected to the United States

* Elected to the United States

Van Allen Probes

(NASA mission, renamed from the Radiation Belt Storm Probes) in 2012

On Nov. 9, 2012 NASA renamed the Radiation Belt Storm Probes (RBSP), a mission to study Earth's Van Allen radiation belts, as the Van Allen Probes mission in honor of the late James A. Van Allen, U.S. space pioneer and longtime distinguished professor of physics in the University of Iowa College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

The

On Nov. 9, 2012 NASA renamed the Radiation Belt Storm Probes (RBSP), a mission to study Earth's Van Allen radiation belts, as the Van Allen Probes mission in honor of the late James A. Van Allen, U.S. space pioneer and longtime distinguished professor of physics in the University of Iowa College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

The

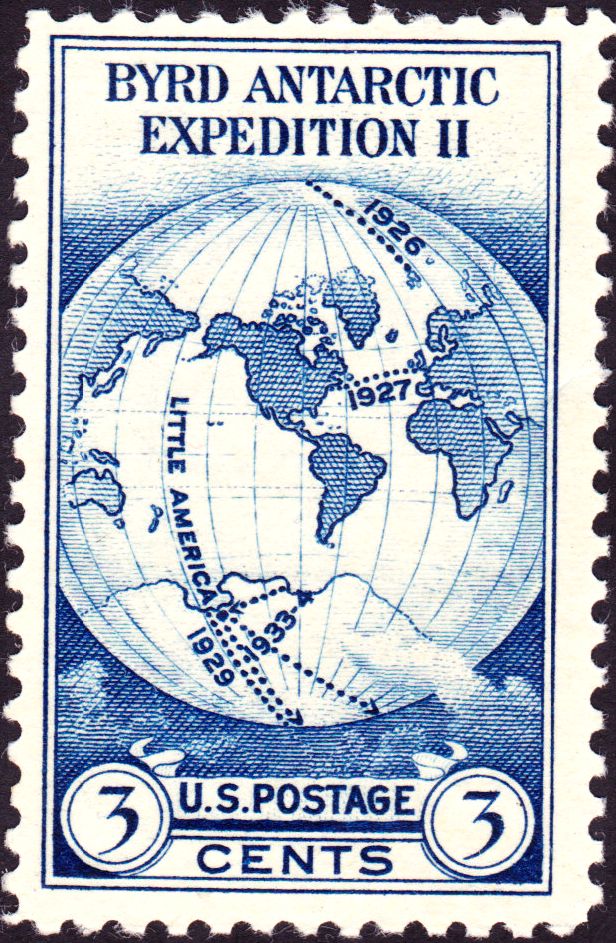

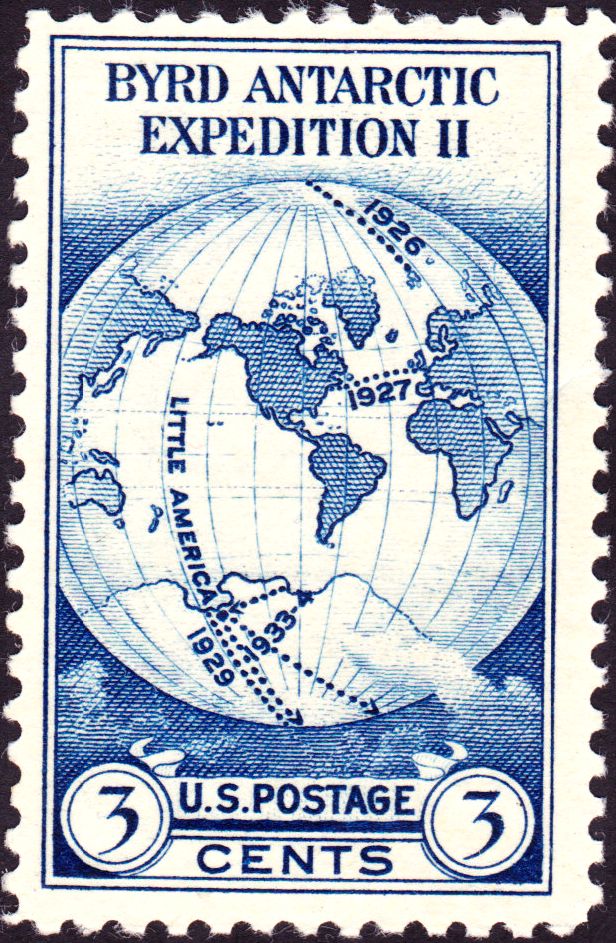

Eighty years after the Second Byrd Expedition, the Balloon Array for RBSP Relativistic Electron Losses (BARREL), a NASA mission began to study Earth's Van Allen radiation belts at the Antarctic (South Pole) managed by

Eighty years after the Second Byrd Expedition, the Balloon Array for RBSP Relativistic Electron Losses (BARREL), a NASA mission began to study Earth's Van Allen radiation belts at the Antarctic (South Pole) managed by

Brief biography

* Foerstner, Abigail; ''James van Allen: The first eight billion miles'', 2007. * Krimigis, Stamatios M.

Planetary Magnetospheres: Van Allen Radiation Belts of the Solar System Planets

* Ludwig, George

The First Explorer Satellites

* Ludwig, George

James Van Allen, From High School to the Beginning of the Space Era: A Biographical Sketch

* McIlwain, Carl

Discovery of the Van Allen Radiation Belts

* NASA

NASA Radiation Belt Storm Probes Mission

* NASA

* ''Nature''

Obituary: James A. Van Allen (1914–2006)

in ''

U.S. Space Pioneer James Van Allen Dies at 91

Space.com * Tabor, Robert

Artist Robert Tabor Depicts the Discovery of Van Allen Radiation Belts

* Thomsen, Michelle

Jupiter's Radiation Belt and Pioneer 10 and 11

* University of Iowa

Van Allen Day

- October 9, 2004 University of Iowa Foundation and UI Department of Astronomy & Physics * University of Iowa

* Van Allen, James A. "Space Science, Space Technology and the Space Station"; ''

What Is A Space Scientist? An Autobiographical Example

* * Van Allen Elementary School in North Liberty, IA

Van Allen elementary homepage

* Van Allen Elementary School in Mt. Pleasant, IA

Van Allen elementary homepage

* Wade, Mark

* Wolverton, Mark

. 2004 *

Legacy''

University of Iowa site including the downloadable data sets from the digitized Explorer I data tapes. * James Van Allen Papers at the University of Iowa Special Collections & University Archive

, an

James Van Allen Papers digital collection

– Iowa Digital Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Van Allen, James 1914 births 2006 deaths American nuclear physicists American people of Dutch descent Iowa Wesleyan University alumni Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences National Medal of Science laureates People from Mount Pleasant, Iowa Recipients of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society University of Iowa alumni University of Iowa faculty Vannevar Bush Award recipients 20th-century American physicists Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Time Person of the Year Members of the American Philosophical Society

University of Iowa

The University of Iowa (UI, U of I, UIowa, or simply Iowa) is a public research university in Iowa City, Iowa, United States. Founded in 1847, it is the oldest and largest university in the state. The University of Iowa is organized into 12 co ...

. He was instrumental in establishing the field of magnetospheric

In astronomy and planetary science, a magnetosphere is a region of space surrounding an astronomical object in which charged particles are affected by that object's magnetic field. It is created by a celestial body with an active interior dynamo. ...

research in space.

The Van Allen radiation belts were named after him, following his discovery using Geiger–Müller tube

The Geiger–Müller tube or G–M tube is the sensing element of the Geiger counter instrument used for the detection of ionizing radiation. It is named after Hans Geiger, who invented the principle in 1908, and Walther Müller, who collaborated ...

instruments on the 1958 satellites

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioisotop ...

(Explorer 1

Explorer 1 was the first satellite launched by the United States in 1958 and was part of the U.S. participation in the International Geophysical Year (IGY). The mission followed the first two satellites the previous year; the Soviet Union's S ...

, Explorer 3

Explorer 3 (Harvard designation 1958 Gamma) was an American artificial satellite launched into medium Earth orbit in 1958. It was the second successful launch in the Explorer program, and was nearly identical to the first U.S. satellite Expl ...

, and Pioneer 3) during the International Geophysical Year

The International Geophysical Year (IGY; french: Année géophysique internationale) was an international scientific project that lasted from 1 July 1957 to 31 December 1958. It marked the end of a long period during the Cold War when scientific i ...

. Van Allen led the scientific community in putting scientific research instruments on space satellites.

Early years and education

Van Allen was born on 7 September 1914 on a small farm near Mount Pleasant, Iowa. As a child, he was fascinated by mechanical and electrical devices and was an avid reader of ''

Van Allen was born on 7 September 1914 on a small farm near Mount Pleasant, Iowa. As a child, he was fascinated by mechanical and electrical devices and was an avid reader of ''Popular Mechanics

''Popular Mechanics'' (sometimes PM or PopMech) is a magazine of popular science and technology, featuring automotive, home, outdoor, electronics, science, do-it-yourself, and technology topics. Military topics, aviation and transportation o ...

'' and ''Popular Science

''Popular Science'' (also known as ''PopSci'') is an American digital magazine carrying popular science content, which refers to articles for the general reader on science and technology subjects. ''Popular Science'' has won over 58 awards, incl ...

'' magazines. He once horrified his mother by constructing a Tesla coil

A Tesla coil is an electrical resonant transformer circuit designed by inventor Nikola Tesla in 1891. It is used to produce high-voltage, low- current, high-frequency alternating-current electricity. Tesla experimented with a number of differen ...

that produced foot-long sparks and caused his hair to stand on end.

A fellowship allowed him to continue studying nuclear physics at the Carnegie Institution in Washington, D.C., where he also became immersed in research in geomagnetism, cosmic ray

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our own ...

s, aurora

An aurora (plural: auroras or aurorae), also commonly known as the polar lights, is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions (around the Arctic and Antarctic). Auroras display dynamic patterns of bri ...

l physics and the physics of Earth's upper atmosphere.

World War II

In August 1939, Van Allen joined the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism (DTM) of the Carnegie Institution in Washington, D.C. as a Carnegie Research Fellow. In the summer of 1940, he joined DTM's national defense efforts with his appointment to a staff position in Section T with theNational Defense Research Committee

The National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) was an organization created "to coordinate, supervise, and conduct scientific research on the problems underlying the development, production, and use of mechanisms and devices of warfare" in the Un ...

(NDRC) in Washington, D.C. where he worked on the development of photoelectric and radio proximity fuze

A proximity fuze (or fuse) is a fuze that detonates an explosive device automatically when the distance to the target becomes smaller than a predetermined value. Proximity fuzes are designed for targets such as planes, missiles, ships at sea, an ...

s, which are detonators that increase the effectiveness of anti-aircraft fire. Another NDRC project later became the atomic bomb Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

in 1941. With the outbreak of World War 2, the proximity fuze work was transferred to the newly created Applied Physics Laboratory

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (Applied Physics Laboratory, or APL) is a not-for-profit university-affiliated research center (UARC) in Howard County, Maryland. It is affiliated with Johns Hopkins University and emplo ...

(APL) of Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

in April 1942. He worked on improving the ruggedness of vacuum tubes subject to the vibration from a gun battery. The work at APL resulted in a new generation of radio-proximity fuses for anti-aircraft defense of ships and for shore bombardment.

Van Allen was commissioned as a U.S. Navy lieutenant in November 1942 and served for 16 months on a succession of South Pacific Fleet destroyers, instructing gunnery officers and conducting tests on his artillery fuses. He was an assistant staff gunnery officer on the battleship USS Washington when the ship successfully defended itself against a Japanese kamikaze attack during the Battle of the Philippine Sea

The Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 19–20, 1944) was a major naval battle of World War II that eliminated the Imperial Japanese Navy's ability to conduct large-scale carrier actions. It took place during the United States' amphibious invas ...

, (June 19–20, 1944). For his actions at the Pacific, Van Allen was awarded four battle stars. He was promoted to lieutenant commander in 1946. "My service as a naval officer was, far and away, the most broadening experience of my lifetime," he wrote in a 1990 autobiographical essay.

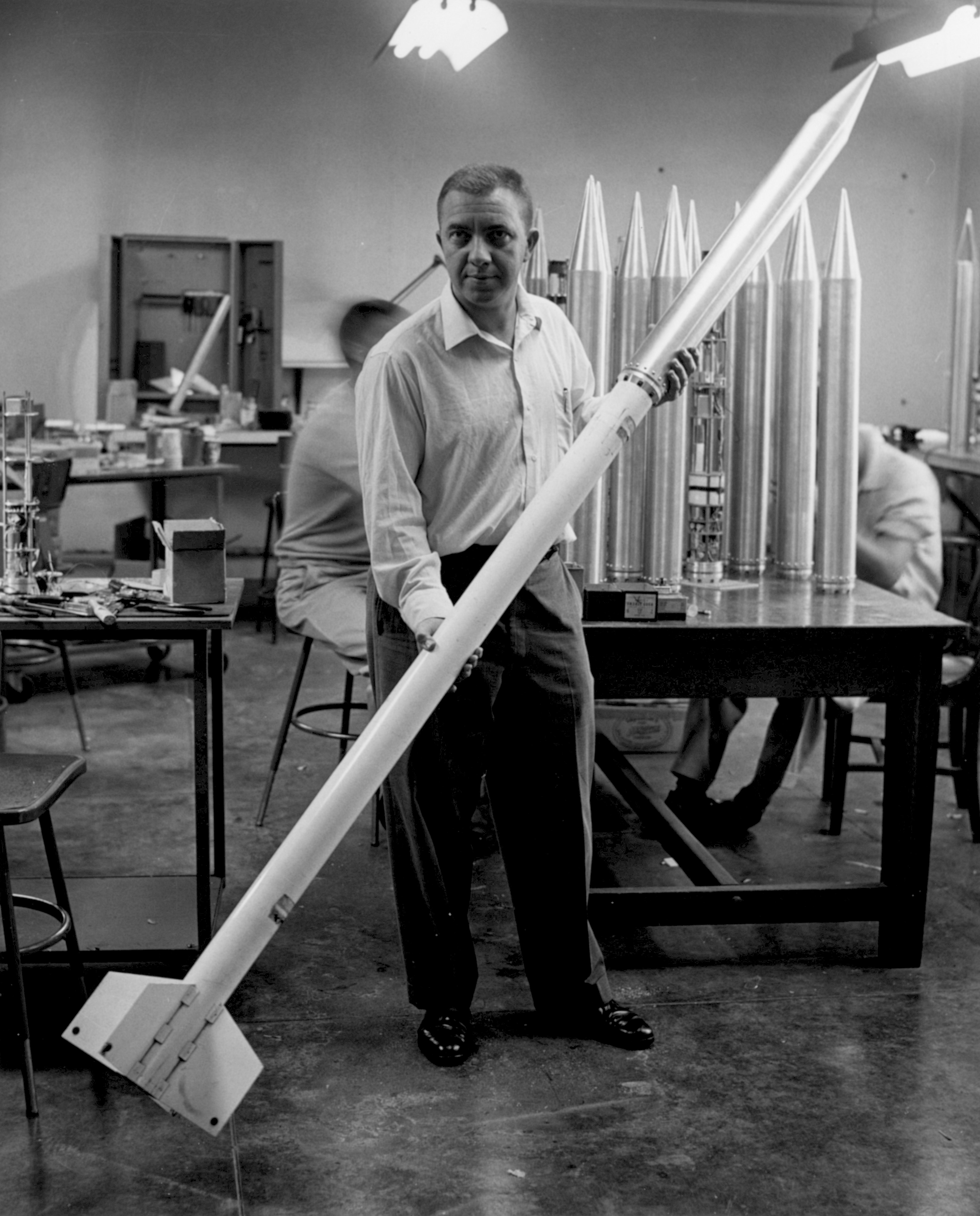

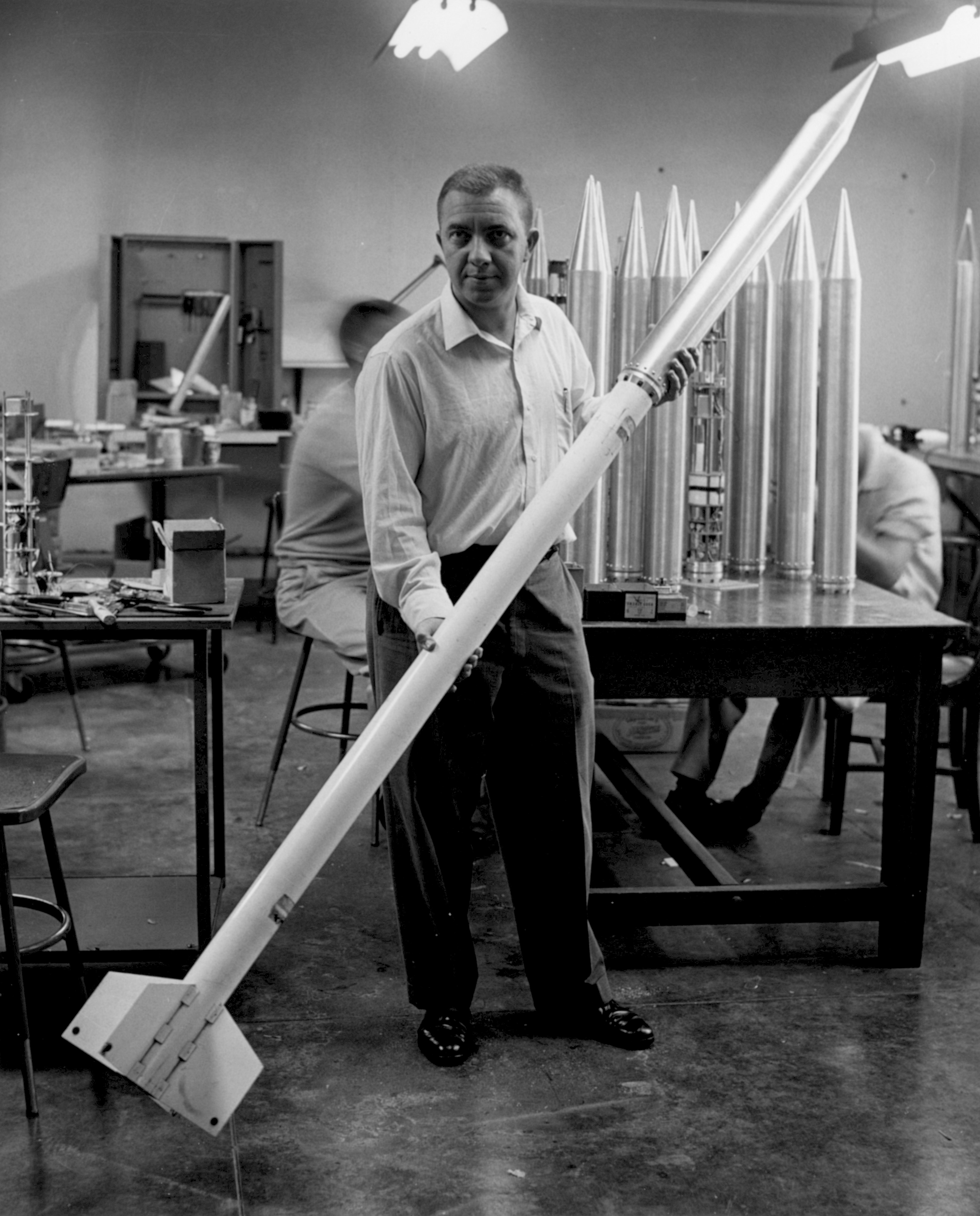

1946-1954 Aerobee and ''Rockoon''

Discharged from the Navy in 1946, Van Allen returned to civilian research at APL. He organized and directed a team at Johns Hopkins University to conduct high-altitude experiments, usingV-2 rocket

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was develop ...

s captured from the Germans at the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. Van Allen decided a small sounding rocket

A sounding rocket or rocketsonde, sometimes called a research rocket or a suborbital rocket, is an instrument-carrying rocket designed to take measurements and perform scientific experiments during its sub-orbital flight. The rockets are used to ...

was needed for upper atmosphere research. The Aerojet WAC Corporal and the Bumblebee missile were developed under a US Navy program. He drew specifications for the Aerobee sounding rocket and headed the committee that convinced the U.S. government to produce it. The first instrument-carrying Aerobee was the A-5, launched on March 5, 1948 from White Sands, New Mexico

White Sands is a census-designated place (CDP) in Doña Ana County, New Mexico, United States. It consists of the main residential area on the White Sands Missile Range. As of the 2010 census the population of the CDP was 1,651. It is part of ...

, carrying instruments for cosmic radiation research, reaching an altitude of 117.5 km.

Van Allen was elected chairman of the V-2

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was develope ...

Upper Atmosphere Panel on December 29, 1947. The panel was renamed Upper Atmosphere Rocket Research Panel on March 18, 1948; then Rocket and Satellite Research Panel on April 29, 1948. The panel suspended operations on May 19, 1960 and had a reunion on February 2, 1968.

Cmdr. Lee Lewis, Cmdr. G. Halvorson, S.F. Singer, and James A. Van Allen developed the idea for the Rockoon

A rockoon (from '' rocket'' and ''balloon'') is a solid fuel sounding rocket that, rather than being immediately lit while on the ground, is first carried into the upper atmosphere by a gas-filled balloon, then separated from the balloon and ...

on March 1, 1949 during the Aerobee rocket firing cruise on the research vessel U.S.S. Norton Sound.

On April 5, 1950, Van Allen left the Applied Physics Laboratory, to accept a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation

The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation was founded in 1925 by Olga and Simon Guggenheim in memory of their son, who died on April 26, 1922. The organization awards Guggenheim Fellowships to professionals who have demonstrated exceptional ...

research fellowship at the Brookhaven National Laboratory

Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory located in Upton, Long Island, and was formally established in 1947 at the site of Camp Upton, a former U.S. Army base and Japanese internment c ...

. The following year (1951) Van Allen accepted the position as head of the physics department at the University of Iowa. Before long, he was enlisting students in his efforts to discover the secrets of the wild blue yonder and inventing ways to carry instruments higher into the atmosphere than ever before. By 1952, Van Allen was the first to devise a balloon-rocket combination that lifted rockets on balloons high above most of the Earth's atmosphere before firing them even higher. The rockets were ignited after the balloons reached an altitude of 16 kilometers.

As ''Time'' magazine later reported, "Van Allen’s ‘

As ''Time'' magazine later reported, "Van Allen’s ‘Rockoon

A rockoon (from '' rocket'' and ''balloon'') is a solid fuel sounding rocket that, rather than being immediately lit while on the ground, is first carried into the upper atmosphere by a gas-filled balloon, then separated from the balloon and ...

s’ could not be fired in Iowa for fear that the spent rockets would strike an Iowan or his house." So Van Allen convinced the U.S. Coast Guard to let him fire his Rockoons from the icebreaker Eastwind

''EastWind'' is an album by Andy Irvine and Davy Spillane, showcasing a fusion of Irish folk music with traditional Bulgarian and Macedonian music. Produced by Irvine and Bill Whelan, who also contributed keyboards and piano, it was widely re ...

that was bound for Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

. "The first balloon rose properly to 70,000 ft., but the rocket hanging under it did not fire. The second Rockoon behaved in the same maddening way. On the theory that extreme cold at high altitude might have stopped the clockwork supposed to ignite the rockets, Van Allen heated cans of orange juice, smuggled them into the third Rockoon’s gondola, and wrapped the whole business in insulation. The rocket fired."

In 1953, the Rockoons and their science payloads fired off Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

detected the first hint of radiation belts surrounding Earth. The low-cost Rockoon technique was later used by the Office of Naval Research

The Office of Naval Research (ONR) is an organization within the United States Department of the Navy responsible for the science and technology programs of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps. Established by Congress in 1946, its mission is to pl ...

and The University of Iowa research groups in 1953–55 and 1957, from ships at sea between Boston and Thule, Greenland

Qaanaaq (), formerly known as Thule or New Thule, is the main town in the northern part of the Avannaata municipality in northwestern Greenland. It is one of the northernmost towns in the world. The inhabitants of Qaanaaq speak the local Inukt ...

.

In 1954, in a private discussion about the Redstone project with Ernst Stuhlinger

Ernst Stuhlinger (December 19, 1913 – May 25, 2008) was a German-American atomic, electrical, and rocket scientist. After being brought to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip, he developed guidance systems with Wernher von Braun's t ...

, Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

expressed his belief that they should have a "real, honest-to-goodness scientist" involved in their little unofficial satellite project. Stuhlinger followed up with a visit to Van Allen at his home in Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton is a municipality with a borough form of government in Mercer County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton and Princeton Township, both of w ...

, where Van Allen was on sabbatical leave from Iowa to work on stellarator

A stellarator is a plasma device that relies primarily on external magnets to confine a plasma. Scientists researching magnetic confinement fusion aim to use stellarator devices as a vessel for nuclear fusion reactions. The name refers to the ...

design. Van Allen later recounted, "Stuhlinger’s 1954 message was simple and eloquent. By virtue of ballistic missile developments at Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA), it was realistic to expect that within a year or two a small scientific satellite could be propelled into a durable orbit around the earth (Project Orbiter

Project Orbiter was a proposed United States spacecraft, an early competitor to Project Vanguard. It was jointly run by the United States Army and United States Navy. It was ultimately rejected by the Ad Hoc Committee on Special Capabilities, wh ...

).... I expressed a keen interest in performing a worldwide survey of the cosmic-ray intensity above the atmosphere."

International Geophysical Year 1957-58

In 1955, the U.S. announced Project Vanguard as part of the US contribution to the

In 1955, the U.S. announced Project Vanguard as part of the US contribution to the International Geophysical Year

The International Geophysical Year (IGY; french: Année géophysique internationale) was an international scientific project that lasted from 1 July 1957 to 31 December 1958. It marked the end of a long period during the Cold War when scientific i ...

. Vanguard planned to launch an artificial satellite into an orbit around the Earth. It was to be run by the US Navy and developed from sounding rocket

A sounding rocket or rocketsonde, sometimes called a research rocket or a suborbital rocket, is an instrument-carrying rocket designed to take measurements and perform scientific experiments during its sub-orbital flight. The rockets are used to ...

s, which had the advantage of being primarily used for non-military scientific experiments.

A symposium on "The Scientific Uses of Earth Satellites" was held on January 26 and 27, 1956 at the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

under sponsorship of the Upper Atmosphere Rocket Research Panel, chaired by Dr. Van Allen. 33 scientific proposals were presented for inclusion in the IGY satellites. Van Allen's presentation highlighted the use of satellites for continuing cosmic-ray investigations. At this same time his Iowa Group began preparations for scientific research instruments to be carried by 'Rockoon

A rockoon (from '' rocket'' and ''balloon'') is a solid fuel sounding rocket that, rather than being immediately lit while on the ground, is first carried into the upper atmosphere by a gas-filled balloon, then separated from the balloon and ...

s' and Vanguard

The vanguard (also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

History

The vanguard derives f ...

for the International Geophysical Year. Through "preparedness and good fortune," as he later wrote, those scientific instruments were available for incorporation in the 1958 Explorer

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

and Pioneer IGY launches.

* July 1, 1957: The International Geophysical Year begins. IGY is carried out by the International Council of Scientific Unions

The International Council for Science (ICSU, after its former name, International Council of Scientific Unions) was an international non-governmental organization devoted to international cooperation in the advancement of science. Its members ...

, over an 18-month period selected to match the period of maximum solar activity (e.g. sun spots). Lloyd Berkner, one of the scientists at the April 5, 1950 Silver Spring, Maryland meeting in Van Allen's home, serves as president of the ICSU from 1957 to 1959.

* September 26, 1957: Thirty-six Rockoons (balloon-launched rockets) were launched from Navy icebreaker U.S.S. Glacier in Atlantic, Pacific, and Antarctic areas ranging from 75° N. to 72° S. latitude, as part of the U.S. International Geophysical Year scientific program headed by Van Allen and Lawrence J. Cahill of The University of Iowa. These were the first known upper atmosphere rocket soundings in the Antarctic area. Launched from IGY Rockoon Launch Site 2, Atlantic Ocean; Latitude: 0.83° N, Longitude: 0.99° W.

* October 4, 1957: The Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

(USSR) successfully launches Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for ...

, the world's first artificial satellite, as part of their participation in the IGY.

* January 31, 1958: The first American satellite,

* January 31, 1958: The first American satellite, Explorer 1

Explorer 1 was the first satellite launched by the United States in 1958 and was part of the U.S. participation in the International Geophysical Year (IGY). The mission followed the first two satellites the previous year; the Soviet Union's S ...

, was launched into Earth's orbit on a Juno I

The Juno I was a four-stage American space launch vehicle, used to launch lightweight payloads into low Earth orbit. The launch vehicle was used between January 1958 to December 1959. The launch vehicle was a member of the Redstone launch ve ...

four-stage booster rocket from Cape Canaveral, Florida

Cape Canaveral ( es, Cabo Cañaveral, link=) is a city in Brevard County, Florida. The population was 9,912 at the 2010 United States Census. It is part of the Palm Bay–Melbourne– Titusville Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

After t ...

. Aboard Explorer 1

Explorer 1 was the first satellite launched by the United States in 1958 and was part of the U.S. participation in the International Geophysical Year (IGY). The mission followed the first two satellites the previous year; the Soviet Union's S ...

were a micrometeorite detector and a cosmic ray experiment designed by Van Allen and his graduate students, with the satellite deployment of the sensor package supervised by Ernst Stuhlinger

Ernst Stuhlinger (December 19, 1913 – May 25, 2008) was a German-American atomic, electrical, and rocket scientist. After being brought to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip, he developed guidance systems with Wernher von Braun's t ...

, who also had an expert cosmic ray background. Data from Explorer 1

Explorer 1 was the first satellite launched by the United States in 1958 and was part of the U.S. participation in the International Geophysical Year (IGY). The mission followed the first two satellites the previous year; the Soviet Union's S ...

and Explorer 3

Explorer 3 (Harvard designation 1958 Gamma) was an American artificial satellite launched into medium Earth orbit in 1958. It was the second successful launch in the Explorer program, and was nearly identical to the first U.S. satellite Expl ...

(launched March 26, 1958) were used by the Iowa group to make "the first space-age scientific discovery": "the existence of a doughnut-shaped region of charged particle radiation trapped by the Earth’s magnetic field".

* July 29, 1958: United States Congress passed the National Aeronautics and Space Act

The National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958 () is the United States federal statute that created the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The Act, which followed close on the heels of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union ...

(commonly called the "Space Act"), which created the National Aeronautics and Space Administration

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding ...

(NASA) as of October 1, 1958 from the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) was a United States federal agency founded on March 3, 1915, to undertake, promote, and institutionalize aeronautical research. On October 1, 1958, the agency was dissolved and its assets ...

(NACA) and other government agencies.

* December 6, 1958: Pioneer 3, the third intended U.S. International Geophysical Year probe under the direction of NASA with the Army acting as executive agent, was launched from the Atlantic Missile Range

The Eastern Range (ER) is an American rocket range (Spaceport) that supports missile and rocket launches from the two major launch heads located at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and the Kennedy Space Center (KSC), Florida. The rang ...

by a Juno II

Juno II was an American space launch vehicle used during the late 1950s and early 1960s. It was derived from the Jupiter missile, which was used as the first stage.

Development

Solid rocket motors derived from the MGM-29 Sergeant were use ...

rocket. The primary objective of the flight, to place the 12.95 pound (5.87 kg) scientific payload in the vicinity of the moon, failed. Pioneer III did reach an altitude of 63,000 miles (101 000 km), providing Van Allen additional data that led to discovery of a second radiation belt. Trapped radiation starts at an altitude of several hundred miles from Earth and extends for several thousand miles into space. The Van Allen radiation belts are named after Van Allen, their discoverer.

Pioneer of space science and exploration

The May 4, 1959 issue of ''Time'' magazine credited James Van Allen as the man most responsible for giving the U.S. "a big lead in scientific achievement." They called Van Allen "a key figure in the cold war’s competition for prestige. .... Today he can tip back his head and look at the sky. Beyond its outermost blue are the world-encompassing belts of fierce radiation that bear his name. No human name has ever been given to a more majestic feature of the planet Earth." James Van Allen, his colleagues, associates and students at The University of Iowa continued to fly scientific instruments on sounding rockets, Earth satellites ( Explorer 52 / Hawkeye 1), and interplanetary spacecraft including the first missions (Pioneer program

The Pioneer programs were two series of United States lunar and planetary space probes exploration. The first program, which ran from 1958 to 1960, unsuccessfully attempted to send spacecraft to orbit the Moon, successfully sent one spacecraft to ...

, Mariner program, Voyager program

The Voyager program is an American scientific program that employs two robotic interstellar probes, ''Voyager 1'' and ''Voyager 2''. They were launched in 1977 to take advantage of a favorable alignment of Jupiter and Saturn, to fly near t ...

, Galileo spacecraft

''Galileo'' was an American robotic space probe that studied the planet Jupiter and its moons, as well as the asteroids Gaspra and Ida. Named after the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, it consisted of an orbiter and an entry probe. It wa ...

) to the planets Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. Their discoveries contributed important segments to the world's knowledge of energetic particles, plasmas and radio waves throughout the solar system.

Van Allen was the principal investigator for scientific investigations on 24 Earth satellites and planetary missions.

Professor emeritus

Van Allen stepped down as the head of the Dept. of Physics & Astronomy in 1985, but continued working at the University of Iowa as the Carver Professor of Physics, Emeritus. On October 9, 2004, the University of Iowa and the UI Alumni Association hosted a celebration to honor Van Allen and his many accomplishments, and in recognition of his 90th birthday. Activities included an invited lecture series, a public lecture followed by a cake and punch reception, and an evening banquet with many of his former colleagues and students in attendance. In August 2005, an elementary school bearing his name opened in North Liberty, Iowa. There is also a Van Allen elementary school in Escalon, CA. In 2009, Van Allen's boyhood home in Mt. Pleasant, once maintained as a museum, was slated to be demolished. The new owner, Lee Pennebaker, chose not to demolish the home. It was donated to the Henry County Heritage Trust, which plans to move the house next to the old Saunders School which will be the home of the Henry County museum.Personal life and death

Van Allen's wife of 61 years was Abigail Fithian Halsey II of Cincinnati (1922–2008). They met at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL) during World War II. They were married October 13, 1945 in Southampton, Long Island. Their five children are Cynthia, Margot, Sarah, Thomas, and Peter. On August 9, 2006, James Van Allen died at University Hospitals inIowa City

Iowa City, offically the City of Iowa City is a city in Johnson County, Iowa, United States. It is the home of the University of Iowa and county seat of Johnson County, at the center of the Iowa City Metropolitan Statistical Area. At the time ...

from heart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome, a group of signs and symptoms caused by an impairment of the heart's blood pumping function. Symptoms typically include shortness of breath, excessive fatigue, ...

.

Professor Van Allen and his wife Abigail are buried in Southampton, New York, where Mrs. Van Allen was born and the couple were married.

Legacy and honors

* Elected to the United States

* Elected to the United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

(1959)

* ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and event (philosophy), events that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various me ...

'' magazine Man of the Year in 1960

* Elliott Cresson Medal

The Elliott Cresson Medal, also known as the Elliott Cresson Gold Medal, was the highest award given by the Franklin Institute. The award was established by Elliott Cresson, life member of the Franklin Institute, with $1,000 granted in 1848. The ...

in 1961

* Elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

(1961)

* Iowa Award in 1961

* Elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

(1964)

* Distinguished Fellow, Iowa Academy of Science in 1975

* Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

The Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society is the highest award given by the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). The RAS Council have "complete freedom as to the grounds on which it is awarded" and it can be awarded for any reason. Past awar ...

in 1978

* National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social scienc ...

in 1987

* Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a non-profit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest achieving individuals in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet ...

in 1988

* Crafoord Prize

The Crafoord Prize is an annual science prize established in 1980 by Holger Crafoord, a Swedish industrialist, and his wife Anna-Greta Crafoord. The Prize is awarded in partnership between the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and the Crafoord Foun ...

in 1989

* Vannevar Bush Award

The National Science Board established the Vannevar Bush Award ( ) in 1980 to honor Vannevar Bush's unique contributions to public service. The annual award recognizes an individual who, through public service activities in science and technolog ...

in 1991

* NASA's Lifetime Achievement Award in 1994

* National Air and Space Museum Trophy in 2006

Van Allen Probes

(NASA mission, renamed from the Radiation Belt Storm Probes) in 2012

Van Allen Probes mission

On Nov. 9, 2012 NASA renamed the Radiation Belt Storm Probes (RBSP), a mission to study Earth's Van Allen radiation belts, as the Van Allen Probes mission in honor of the late James A. Van Allen, U.S. space pioneer and longtime distinguished professor of physics in the University of Iowa College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

The

On Nov. 9, 2012 NASA renamed the Radiation Belt Storm Probes (RBSP), a mission to study Earth's Van Allen radiation belts, as the Van Allen Probes mission in honor of the late James A. Van Allen, U.S. space pioneer and longtime distinguished professor of physics in the University of Iowa College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

The Applied Physics Laboratory

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (Applied Physics Laboratory, or APL) is a not-for-profit university-affiliated research center (UARC) in Howard County, Maryland. It is affiliated with Johns Hopkins University and emplo ...

, where Dr. Van Allen worked for a decade, is responsible for the overall implementation and instrument management for RBSP. The primary mission is scheduled to last 2 years, with expendables expected to last for 4 years.

NASA BARREL mission

Eighty years after the Second Byrd Expedition, the Balloon Array for RBSP Relativistic Electron Losses (BARREL), a NASA mission began to study Earth's Van Allen radiation belts at the Antarctic (South Pole) managed by

Eighty years after the Second Byrd Expedition, the Balloon Array for RBSP Relativistic Electron Losses (BARREL), a NASA mission began to study Earth's Van Allen radiation belts at the Antarctic (South Pole) managed by Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College (; ) is a private research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, it is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. Although founded to educate Native ...

. BARREL launched 20 balloons from Antarctica during each of two balloon campaigns in January–February 2013 and December 2013 – February 2014. This scientific data will complement the Van Allen Probes data over the two-year mission.

See also

* George H. Ludwig * Stamatios Krimigis (Tom Krimigis) * Explorer program * Sputnik program *Sputnik crisis

The Sputnik crisis was a period of public fear and anxiety in Western Bloc, Western nations about the perceived technological gap between the United States and Soviet Union caused by the Soviets' launch of ''Sputnik 1'', the world's first arti ...

* Pioneer 10

''Pioneer 10'' (originally designated Pioneer F) is an American space probe, launched in 1972 and weighing , that completed the first mission to the planet Jupiter. Thereafter, ''Pioneer 10'' became the first of five artificial objects to ac ...

, Pioneer 11

''Pioneer 11'' (also known as ''Pioneer G'') is a robotic space probe launched by NASA on April 5, 1973, to study the asteroid belt, the environment around Jupiter and Saturn, solar winds, and cosmic rays. It was the first probe to encoun ...

, Pioneer H

Notes

References

Brief biography

* Foerstner, Abigail; ''James van Allen: The first eight billion miles'', 2007. * Krimigis, Stamatios M.

Planetary Magnetospheres: Van Allen Radiation Belts of the Solar System Planets

* Ludwig, George

The First Explorer Satellites

* Ludwig, George

James Van Allen, From High School to the Beginning of the Space Era: A Biographical Sketch

* McIlwain, Carl

Discovery of the Van Allen Radiation Belts

* NASA

NASA Radiation Belt Storm Probes Mission

* NASA

* ''Nature''

Obituary: James A. Van Allen (1914–2006)

in ''

Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

'', 14 September 2006.

* Dvorak, Todd. (9 August 2006U.S. Space Pioneer James Van Allen Dies at 91

Space.com * Tabor, Robert

Artist Robert Tabor Depicts the Discovery of Van Allen Radiation Belts

* Thomsen, Michelle

Jupiter's Radiation Belt and Pioneer 10 and 11

* University of Iowa

Van Allen Day

- October 9, 2004 University of Iowa Foundation and UI Department of Astronomy & Physics * University of Iowa

* Van Allen, James A. "Space Science, Space Technology and the Space Station"; ''

Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it ...

'', January 1986, page 22.

* Van Allen, JamesWhat Is A Space Scientist? An Autobiographical Example

* * Van Allen Elementary School in North Liberty, IA

Van Allen elementary homepage

* Van Allen Elementary School in Mt. Pleasant, IA

Van Allen elementary homepage

* Wade, Mark

* Wolverton, Mark

. 2004 *

External links

Legacy''

University of Iowa site including the downloadable data sets from the digitized Explorer I data tapes. * James Van Allen Papers at the University of Iowa Special Collections & University Archive

, an

James Van Allen Papers digital collection

– Iowa Digital Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Van Allen, James 1914 births 2006 deaths American nuclear physicists American people of Dutch descent Iowa Wesleyan University alumni Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences National Medal of Science laureates People from Mount Pleasant, Iowa Recipients of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society University of Iowa alumni University of Iowa faculty Vannevar Bush Award recipients 20th-century American physicists Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Time Person of the Year Members of the American Philosophical Society