Jairamdas Daulatram on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jairamdas Daulatram (1891–1979) was an Indian political leader from

From 1950 to 1956, Daulatram served as the

From 1950 to 1956, Daulatram served as the

Sindh

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

, who was active in the Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947.

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged ...

and later served in the Government of India. He was appointed as the Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

for the states of Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West Be ...

and later Assam

Assam (; ) is a state in northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . The state is bordered by Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh to the north; Nagaland and Manipur ...

. He played a key role in strengthening the North-East Frontier Tracts

The North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), originally known as the North-East Frontier Tracts (NEFT), was one of the political divisions in British India, and later the Republic of India until 20 January 1972, when it became the Union Territory of ...

of India in the face of the Chinese annexation of Tibet

Tibet came under the control of People's Republic of China (PRC) after the Government of Tibet signed the Seventeen Point Agreement which the 14th Dalai Lama ratified on 24 October 1951, but later repudiated on the grounds that he rendered hi ...

, and managed the Indian integration of Tawang

Tawang is a town and administrative headquarter of Tawang district in the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. The town was once the capital of the Tawang Tract, which is now divided into the Tawang district and the West Kameng district. Tawang c ...

in 1951.

Early life

Jairamdas Daulatram was born into a SindhiHindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

family in Karachi

Karachi (; ur, ; ; ) is the most populous city in Pakistan and 12th most populous city in the world, with a population of over 20 million. It is situated at the southern tip of the country along the Arabian Sea coast. It is the former cap ...

, Sindh

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

, which was then part of the Bombay Presidency

The Bombay Presidency or Bombay Province, also called Bombay and Sind (1843–1936), was an administrative subdivision (province) of British India, with its capital in the city that came up over the seven islands of Bombay. The first mainl ...

in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

on 21 July 1891.

After receiving a degree in law, he started a legal practice, but soon gave it up as it often led to conflict with his conscience. In 1915, Daulatram came into contact with Mahatma Gandhi, who had then returned from South Africa, and became his devoted follower. At the Amritsar session of the Indian National Congress in 1919, he worded Gandhi's resolution in such a way that it avoided an impending rift between Gandhi and his other Congress colleagues. Since then Gandhi came to repose great faith in him. He compared him with pure gold saying : 'I swear by Jairamdas. Truer man I have not had the honour of meeting.' Jairamdas enjoyed the trust and affection of Mrs. Sarojini Naidu who described his as a 'Lamp in the Desert' because of his services in the Sindh, which was mostly a desert. His ties with Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (; ; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar, was an Indian lawyer, influential political leader, barrister and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister of I ...

and Rajendra Prasad

Rajendra Prasad (3 December 1884 – 28 February 1963) was an Indian politician, lawyer, Indian independence activist, journalist & scholar who served as the first president of Republic of India from 1950 to 1962. He joined the Indian Nationa ...

were also very close.

Freedom struggle

Daulatram became an activist in theHome Rule Movement

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a State (polity), state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers o ...

led by Annie Besant

Annie Besant ( Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was a British socialist, theosophist, freemason, women's rights activist, educationist, writer, orator, political party member and philanthropist.

Regarded as a champion of human f ...

and Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (, ; born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 1876 – 11 September 1948) was a barrister, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the ...

, demanding "Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

", or self-government and Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

status for India within the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. He also joined the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Em ...

, which was the largest Indian political organisation. Daulatram was deeply influenced by the philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, which advocated simple living, and a struggle for independence through ''ahimsa

Ahimsa (, IAST: ''ahiṃsā'', ) is the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence which applies to all living beings. It is a key virtue in most Indian religions: Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.Bajpai, Shiva (2011). The History of India � ...

'' (non-violence) and ''satyagraha

Satyagraha ( sa, सत्याग्रह; ''satya'': "truth", ''āgraha'': "insistence" or "holding firmly to"), or "holding firmly to truth",' or "truth force", is a particular form of nonviolent resistance or civil resistance. Someone w ...

''. perhaps Gandhi's sweetest relations were with Daulatram. At the Amritsar session of the Congress, 1919, acute differences had arisen on the reforms resolution between Gandhiji on the one hand and Tilak, C.R. Das and Mohammed Ali on the other. Recalled Gandhiji years later: ``Jairamdas, that cool-headed Sindhi, came to the rescue. He passed me a slip containing a suggestion and pleading for a compromise. I hardly knew him. Something in his eyes and face captivated me. l read the suggestion. It was good. I passed it on to Deshbandhu. "Yes, if my party Will accept it" was his response. Lokmanya said, "I don't want to see it. If Das has approved, it is good enough for me.' Malaviya (who was presiding anxiously) overheard it, snatched the paper from my hands and, amid deafening cheers, announced that a compromise had been arrived at."

When Gandhi was launching the Salt March

The Salt March, also known as the Salt Satyagraha, Dandi March and the Dandi Satyagraha, was an act of nonviolent civil disobedience in colonial India led by Mahatma Gandhi. The twenty-four day march lasted from 12 March to 6 April 1930 as a di ...

in 1930, he wrote to Daulatram, who was then member of the Bombay Legislative Council: "I have taken charge of the Committee for Boycott of Foreign Cloth. I must have a whole-time secretary, if that thing is to work. And I can think of nobody so suitable like you." Daulatram immediately resigned his seat, took up the new charge, and made a tremendous success of the boycott of foreign cloth.

Daulatram participated in the Non-cooperation movement

The Non-cooperation movement was a political campaign launched on 4 September 1920, by Mahatma Gandhi to have Indians revoke their cooperation from the British government, with the aim of persuading them to grant self-governance.

(1920–1922), agitating against British rule through non-violent

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". Hen ...

. Daulatram rose in the ranks of the Congress and became one of its foremost leaders from Sindh. He was a leading activist in the Salt March (1930–31) and the Quit India movement

The Quit India Movement, also known as the August Kranti Movement, was a movement launched at the Bombay session of the All India Congress Committee by Mahatma Gandhi on 8th August 1942, during World War II, demanding an end to British rule in ...

(1942–45), being imprisoned by British authorities. Daulatram was shot and wounded in the thigh when police opened fire on street protesters agitating outside a magistrate's court in Karachi in 1930.

Post-independence career

In the 1947Partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the Partition (politics), change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: ...

, Daulatram's native Sindh was included in newly created state of Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, with Karachi as its capital. Daulatram stayed in India and was appointed the first Indian Governor of Bihar

The governor of Bihar is a nominal head and representative of the President of India in the state of Bihar. The Governor is appointed by the President for a term of 5 years. Phagu Chauhan is the current governor of Bihar. Former President Zaki ...

, a post he held until 1948. Then he was appointed the Union Minister for Food Supply. He represented a constituency from East Punjab

East Punjab (known simply as Punjab from 1950) was a province and later a state of India from 1947 until 1966, consisting of the parts of the Punjab Province of British India that went to India following the partition of the province between ...

in the Constituent Assembly of India

The Constituent Assembly of India was elected to frame the Constitution of India. It was elected by the 'Provincial Assembly'. Following India's independence from the British rule in 1947, its members served as the nation's first Parliament as ...

and contributed to the drafting of the Constitution of India

The Constitution of India (IAST: ) is the supreme law of India. The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures, powers, and duties of government institutions and sets out fundamental ri ...

. He served as a member of the advisory, union subjects, and provincial constitution committees.

Governor of Assam

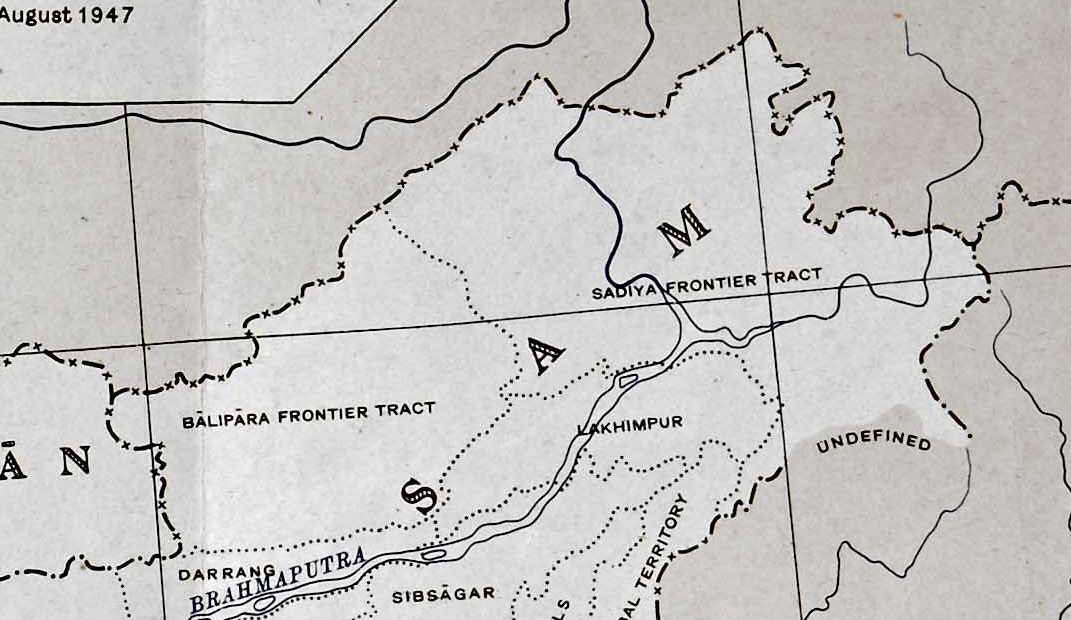

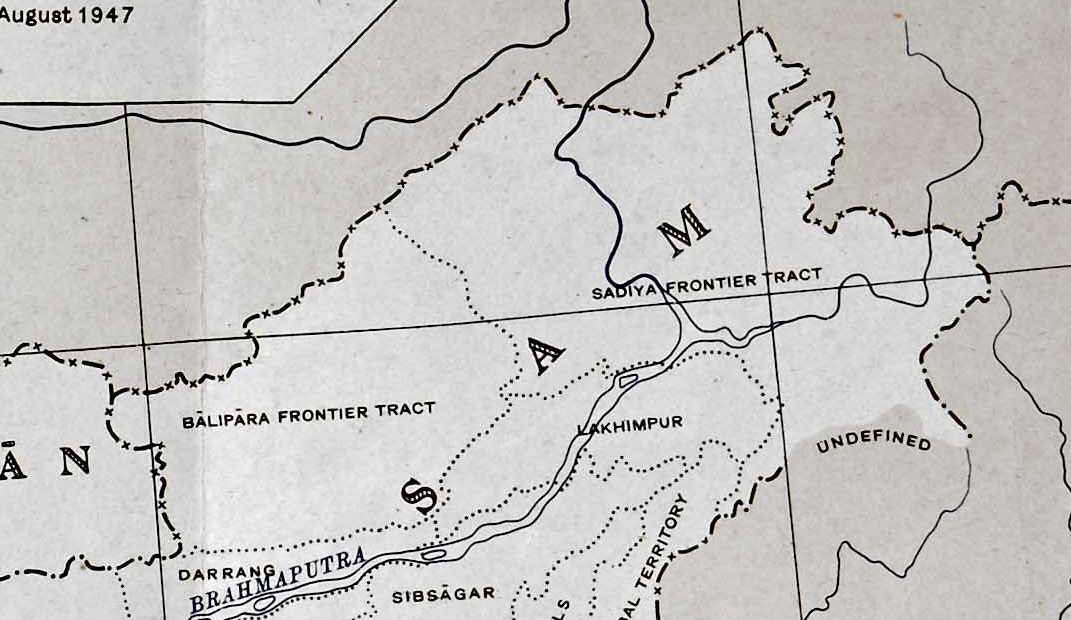

From 1950 to 1956, Daulatram served as the

From 1950 to 1956, Daulatram served as the Governor of Assam

This is a list of governors of Assam, and other offices of similar scope, from the start of British occupation of the area in 1824 during the First Anglo-Burmese War.

The Governor of Assam is a nominal head and representative of the President ...

, in a crucial period which saw the Chinese annexation of Tibet

Tibet came under the control of People's Republic of China (PRC) after the Government of Tibet signed the Seventeen Point Agreement which the 14th Dalai Lama ratified on 24 October 1951, but later repudiated on the grounds that he rendered hi ...

. The North-East Frontier Tracts

The North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), originally known as the North-East Frontier Tracts (NEFT), was one of the political divisions in British India, and later the Republic of India until 20 January 1972, when it became the Union Territory of ...

(better known as North-East Frontier Agency

The North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), originally known as the North-East Frontier Tracts (NEFT), was one of the political divisions in British India, and later the Republic of India until 20 January 1972, when it became the Union Territory of ...

, and later Arunachal Pradesh

Arunachal Pradesh (, ) is a state in Northeastern India. It was formed from the erstwhile North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) region, and became a state on 20 February 1987. It borders the states of Assam and Nagaland to the south. It shares int ...

) were under the direct administration of the Governor in that period. After the Chinese made advances into Tibet in October 1950 with the avowed purpose of annexing it, the Union home minister Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (; ; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar, was an Indian lawyer, influential political leader, barrister and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister of I ...

laid out a detailed programme of action for India to strengthen its frontiers against Tibet. Much of this programme fell on Daulatram's shoulders as the frontier tracts shared a long semi-settled border with Tibet. By December 1950, it was clear that the Chinese troops had occupied eastern Tibet up to Zayul

Zayul County

()

KNAB, retrieved 5 July 2021. Mishmi tribes. Daulatram sent Assam Rifles platoons to man the border in winter. In December 1950, preparations were also made to occupy

Saving Tawang: How the Tawang Tract was saved for India

Indian Defence Reivew, 15 February 2021.

KNAB, retrieved 5 July 2021. Mishmi tribes. Daulatram sent Assam Rifles platoons to man the border in winter. In December 1950, preparations were also made to occupy

Tawang

Tawang is a town and administrative headquarter of Tawang district in the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. The town was once the capital of the Tawang Tract, which is now divided into the Tawang district and the West Kameng district. Tawang c ...

. The area around the Tawang village and monastery, i.e., the present day Tawang district

Tawang district (Pron:/tɑ:ˈwæŋ or təˈwæŋ/) is the smallest of the 26 administrative districts of Arunachal Pradesh state in northeastern India. With a population of 49,977, it is the eighth least populous district in the country (out of ...

, had not been integrated into frontier tracts when the British departed from India. It was vaguely administered by the Tawang Monastery

Tawang Monastery, located in Tawang city of Tawang district in the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, is the largest monastery in India. It is situated in the valley of the Tawang Chu, near the small town of the same name in the northwestern p ...

under the supervision of lamas from Tibet's Tsona Dzong. In January 1951, Daulatram appointed Major Ralengnao Khathing

Ralengnao Khathing Military Cross, MC, Order of the British Empire, MBE (1912–1990) popularly known as Bob Khathing, was an Indian soldier, civil servant and diplomat and the first person of tribal origin to serve as an Ambassador for India.

...

("Bob Khathing") of the Indian Frontier Administration Service as the Assistant Political Officer of the Sela Subagency and instructed him on the importance of speedy integration of Tawang into the Subagency.

Khathing set out from Tezpur

Tezpur () is a city and urban agglomeration in Sonitpur district, Assam state, India. Tezpur is located on the banks of the river Brahmaputra, northeast of Guwahati, and is the largest of the north bank cities with a population exceeding 100, ...

with 200 troops of Assam Rifles

The Assam Rifles (AR) is a central paramilitary force responsible for border security, counter-insurgency, and maintaining law and order in Northeast India. It guards the Indo-Myanmar border. The Assam rifles is the oldest paramilitary force ...

on 17 January 1951, reaching Tawang on 7 February. He had his men do a flag march around Tawang with bayonets fixed to their guns in order to send a message that he meant business. He visited the Tawang Monastery on 11 February, paid respects to the lamas, and then ordered all the local officials that, from then on, no orders should be taken from the Tibetan lamas. When the lamas objected, he informed them that Tawang had been part of India since the Treaty of 1914.

The lamas evidently complained to the central Tibetan administration in Lhasa, who in turn complained to the Indian External Affairs Ministry, which was headed by Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

. Apparently Nehru had not authorised the take-over of Tawang, and he ordered Daulatram and Khathing to come to Delhi to explain the matter. Scholar Sonia Shukla, who investigated the official correspondence, found that the Ministry was certainly aware of Daulatram's actions and had in fact authorised them. They perhaps kept Nehru in the dark for fear that he might not act decisively. Vallabhbhai Patel, who had died in December 1950, apparently initiated a sequence of actions that the officials were following.

Preservation of Sindhi literature

Jairamdas Daulatram was one of the founding members of the Akhil Bharat Sindhi Boli Ain Sahit Sabha (All India Sindhi Language and Literature Congress).Legacy

Daulatram died in 1979. He was said to have been still a poor man, sticking to his Gandhian ideals. The town of Jarampur in the erstwhile Tirap Frontier Division (now Changlang district) was named after him. In 1985, a postage stamp was issued in his honour.Joydeep SircarSaving Tawang: How the Tawang Tract was saved for India

Indian Defence Reivew, 15 February 2021.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Daulatram, Jairamdas Indian independence activists from Pakistan 1891 births 1979 deaths Sindhi people Governors of Bihar Governors of Assam Members of the Constituent Assembly of India Politicians from Karachi Nominated members of the Rajya Sabha Prisoners and detainees of British India Indian National Congress politicians Members of the Central Legislative Assembly of India Agriculture Ministers of India