Józef Retinger on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

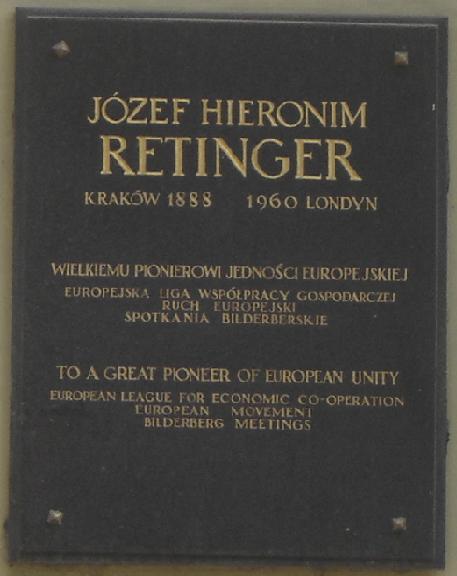

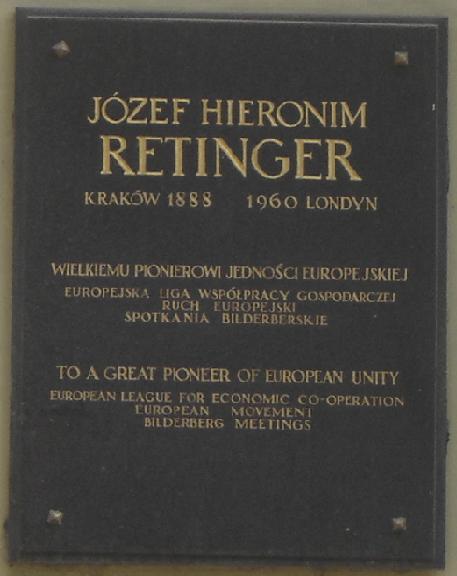

Józef Hieronim Retinger (World War II noms de guerre ''Salamandra'', "Salamander", and ''Brzoza'', "Birch Tree"; 17 April 1888 – 12 June 1960) was a Polish politician, scholar, international political activist with access to some of the leading power brokers of the 20th century, a publicist and writer.

Already as a gifted student in

With war clouds closing in, the project of writing a play together with Conrad based on the latter's novel, ''

With war clouds closing in, the project of writing a play together with Conrad based on the latter's novel, ''

Retinger travelled on to

Retinger travelled on to

on 21 March 1943 referred to the necessity of smaller nations forming groupings, but that it was too early to go into detail. The most Retinger was able to achieve was to push through the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement, signed on 30 July 1941, which provided for the formation of the Anders' army, thus ridding Stalin of the immediate human problem posed by the hundreds of thousands of Polish

The latter reference was to elements in the Polish underground

The latter reference was to elements in the Polish underground

After World War II, Retinger feared another devastating war in Europe, this time fought between "Russia" and "the Anglo-Saxons". He became a leading advocate of European unification as a means of securing peace. He helped found both the

After World War II, Retinger feared another devastating war in Europe, this time fought between "Russia" and "the Anglo-Saxons". He became a leading advocate of European unification as a means of securing peace. He helped found both the

Illustrated biography of Jozef Retinger assembled by Jan Chciuk-Celt

Polish Soviet Relations During The Second World War

photographs held by the

Photograph of Retinger flanking Churchill at the Hague 1948, on Retinger's grandson's website

* ttp://bilderbergmeetings.co.uk/jozef-retinger/ Bilderberg website on Retinger's life in brief {{DEFAULTSORT:Retinger, Jozef 1888 births 1960 deaths Ambassadors of Poland to the Soviet Union Council of Europe people Members of the Steering Committee of the Bilderberg Group Polish politicians University of Paris alumni Alumni of the University of London Polish Freemasons European integration pioneers Geopoliticians Polish emigrants to the United Kingdom Polish diplomats Polish spies MI6 personnel Special Operations Executive personnel 20th-century Polish writers Exophonic writers Polish essayists Polish male essayists Polish political writers Polish people of World War II History of the European Union Polish people of Jewish descent Polish people of Rusyn descent Burials at North Sheen Cemetery

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

and London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

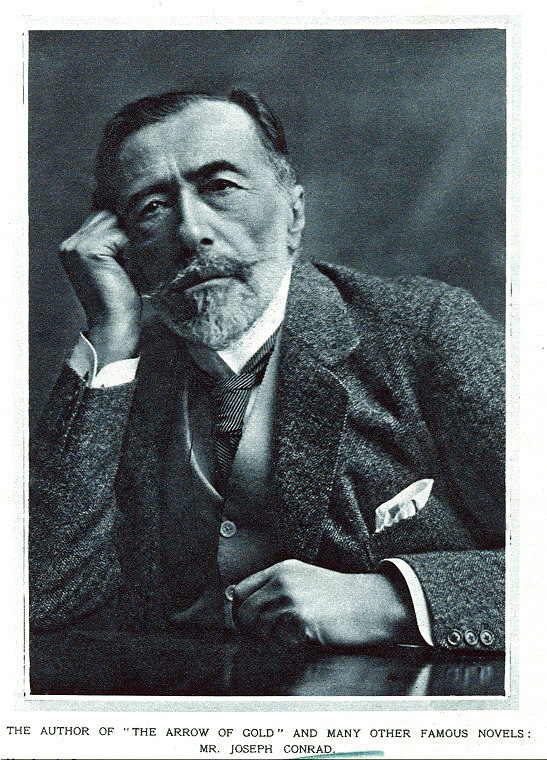

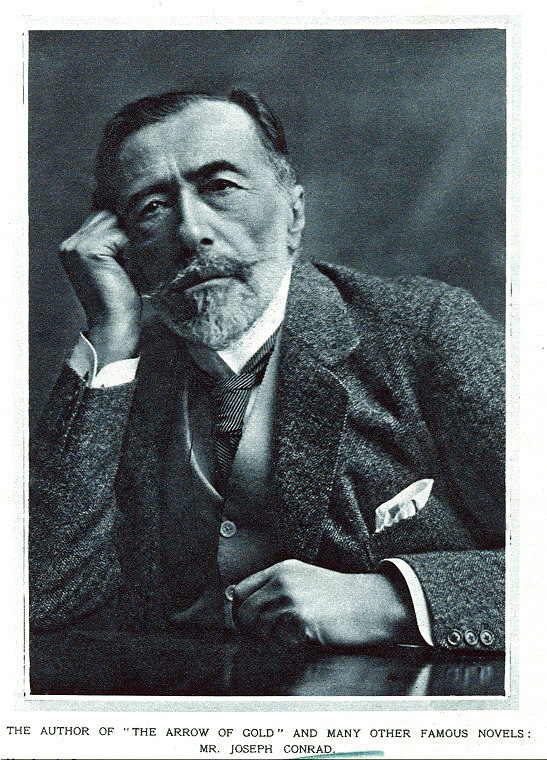

he mixed with the leading lights of music and literature. Most notably, he became a friend of compatriot Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the Eng ...

. During World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the young Retinger became politically active in Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

and Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

on behalf of the Polish independence movement. Following a failed attempt to broker peace between Austria-Hungary and the Allies of World War I

The Allies or the Entente (, ) was an international military coalition of countries led by the French Republic, the United Kingdom, the Russian Empire, the United States, the Kingdom of Italy, and the Empire of Japan against the Central Powers ...

, he had to retreat to Central America

Central America is a subregion of North America. Its political boundaries are defined as bordering Mexico to the north, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest. Central America is usually ...

, where he became an economic adviser.

After the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he was principal adviser to the Polish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile (), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent Occupation ...

. Early in 1944, a daring mission into Occupied Poland

' (Norwegian language, Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV 2 (Norway), TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. ...

by parachute, with the help of British intelligence, added to his air of mystery and subsequent controversy. A Freemason with a reputation as a grey eminence, after World War II he went on to co-found the European Movement

The European Movement International is a lobbying association that coordinates the efforts of associations and national councils with the goal of promoting European integration, and disseminating information about it.

History

Initially the Euro ...

, which led to the establishment of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

, and was instrumental in forming the secretive Bilderberg Group

The Bilderberg Meeting (also known as the "Bilderberg Group", "Bilderberg Conference" or "Bilderberg Club") is an annual off-the-record forum established in 1954 to foster dialogue between Europe and North America. The group's agenda, originally ...

. In 1958, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

.

Early life

Józef Retinger was born inKraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

(then part of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

), the youngest of five children: his father had a daughter, Aniela, from a first marriage to Helena Jawornicka. His mother was Maria Krystyna Czyrniańska, daughter of a Greek Catholic Greek Catholic Church or Byzantine-Catholic Church may refer to:

* The Catholic Church in Greece

* The Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also known as the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Ea ...

Lemko

Lemkos (; ; ; ) are an ethnic group inhabiting the Lemko Region (; ) of Carpathian Ruthenia, Carpathian Rus', an ethnographic region in the Carpathian Mountains and Carpathian Foothills, foothills spanning Ukraine, Slovakia, and Poland.

Lemkos ...

professor of chemistry at the Jagiellonian University

The Jagiellonian University (, UJ) is a public research university in Kraków, Poland. Founded in 1364 by Casimir III the Great, King Casimir III the Great, it is the oldest university in Poland and one of the List of oldest universities in con ...

. His father, Józef Stanisław Retinger, was the personal legal counsel and successful adviser to French-born Count Władysław Zamoyski

Count Władysław Zamoyski (1853–1924) was a French-born Poland, Polish nobleman (szlachcic), diplomat and heir of Kórnik, Głuchów, Łódź East County, Głuchów, Janusz, Łódź Voivodeship, Janusz, Babin Potok, Donji Vakuf, Babin an ...

. Retinger's great-grandfather, Filip Rettinger, was a Jewish tailor from Tarnów

Tarnów () is a city in southeastern Poland with 105,922 inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of 269,000 inhabitants. The city is situated in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship. It is a major rail junction, located on the strategic east– ...

who with his family converted to Catholicism in 1827. When his lawyer grandson died, Count Zamoyski took the promising youngster, Józef, into his household and paid for him to attend the Bartłomiej Nowodworski High School in Kraków. Retinger's eldest brother, Emil, became a commander in the Polish Navy

The Polish Navy (; often abbreviated to ) is the Navy, naval military branch , branch of the Polish Armed Forces. The Polish Navy consists of 46 ships and about 12,000 commissioned and enlisted personnel. The traditional ship prefix in the Polish ...

, while his son, , was stationed in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

(1943–45), as a member then leader of Squadron 308 of the Polish Air Force

The Polish Air Force () is the aerial warfare Military branch, branch of the Polish Armed Forces. Until July 2004 it was officially known as ''Wojska Lotnicze i Obrony Powietrznej'' (). In 2014 it consisted of roughly 26,000 military personnel an ...

. Retinger's brother, Juliusz, taught physiological chemistry at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

and University of Wilno. Retinger himself initially considered a career in the priesthood, but three months in the Jesuit novitiate

The novitiate, also called the noviciate, is the period of training and preparation that a Christian ''novice'' (or ''prospective'') monastic, apostolic, or member of a religious order undergoes prior to taking vows in order to discern whether ...

in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

confirmed he would not be suited to the life.

Further financed by Count Zamoyski in 1906, Retinger entered simultaneously the Ecole des sciences politiques and the Sorbonne in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

and two years later, aged twenty, became the youngest person ever to earn a Ph.D. in literature from there. While in the French capital, armed with introductions from Zamoyski and his own relative, the salonnière and pianist Misia Sert

Misia Sert (born Maria Zofia Olga Zenajda Godebska; 30 March 1872 – 15 October 1950) was known primarily as a patron of contemporary artists and musicians during the decades she hosted salons in her homes in Paris. Born in the Russian Empire and ...

, he moved in intellectual circles and was befriended by among others, André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide (; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French writer and author whose writings spanned a wide variety of styles and topics. He was awarded the 1947 Nobel Prize in Literature. Gide's career ranged from his begi ...

, François Mauriac

François Charles Mauriac (; ; 11 October 1885 – 1 September 1970) was a French novelist, dramatist, critic, poet, and journalist, a member of the'' Académie française'' (from 1933), and laureate of the 1952 Nobel Prize in Literature, Nobel Pr ...

, , Jean Giraudoux

Hippolyte Jean Giraudoux (; ; 29 October 1882 – 31 January 1944) was a French novelist, essayist, diplomat and playwright. He is considered among the most important French dramatists of the period between World War I and World War II.

His wo ...

, Erik Satie

Eric Alfred Leslie Satie (born 17 May 18661 July 1925), better known as Erik Satie, was a French composer and pianist. The son of a French father and a British mother, he studied at the Conservatoire de Paris, Paris Conservatoire but was an undi ...

and Maurice Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism in music, Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composer ...

. His early literary ambitions were stopped in their tracks when he presented his first novel, ''Les Souffleurs'', to André Gide for his opinion. Gide told him: "Joseph, you will never be a writer."

He next went to Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

to study comparative psychology

Comparative psychology is the scientific study of the behavior and mental processes of non-human animals, especially as these relate to the phylogenetic history, adaptive significance, and development of behavior. The phrase comparative psycholog ...

for a year. From there, encouraged by Zamoyski, in 1910 he moved to England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, where he entered the London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), established in 1895, is a public research university in London, England, and a member institution of the University of London. The school specialises in the social sciences. Founded ...

for a year's study and began a lobbying operation on behalf of the Polish cause and its populations scattered across three ailing empires. Formally he became Director of the London Office of the Polish National Committee (1912–1914). During this time he continued to move in élite circles and thanks to an introduction by Arnold Bennett

Enoch Arnold Bennett (27 May 1867 – 27 March 1931) was an English author, best known as a novelist, who wrote prolifically. Between the 1890s and the 1930s he completed 34 novels, seven volumes of short stories, 13 plays (some in collaborati ...

whom he had met in Paris, Retinger developed a close friendship with his older Polish compatriot, the already well established novelist, Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the Eng ...

. Retinger urged Conrad to visit Poland, and on 28 July 1914, the day World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

broke out, Retinger, his wife Otolia, and Conrad, his wife, and their two sons arrived in Kraków, the two men's childhood stamping grounds (they were alumni of the same secondary school

A secondary school, high school, or senior school, is an institution that provides secondary education. Some secondary schools provide both ''lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper secondary education'' (ages 14 to 18), i.e., b ...

). Due to the closeness of the Russian border (Russia was then allied to Great Britain), the Conrads soon sought greater safety in the Tatra Mountains resort of Zakopane

Zakopane (Gorals#Language, Podhale Goral: ''Zokopane'') is a town in the south of Poland, in the southern part of the Podhale region at the foot of the Tatra Mountains. From 1975 to 1998, it was part of Nowy Sącz Voivodeship; since 1999, it has ...

. Retinger would write about Conrad in his 1943 book, ''Conrad and His Contemporaries''. Historian Norman Davies

Ivor Norman Richard Davies (born 8 June 1939) is a British and Polish historian, known for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland and the United Kingdom. He has a special interest in Central and Eastern Europe and is UNESCO Profes ...

suggests that it was probably Conrad who introduced the "polyglot and polymath" Retinger to the British intelligence services. Later Retinger became a personal friend of Major-General Sir Colin Gubbins

Major-General Sir Colin McVean Gubbins, (2 July 1896 – 11 February 1976) was the prime mover of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in the Second World War.

Gubbins was also responsible for setting up the secret Auxiliary Units, a comman ...

, wartime head of SOE, and after the war an MI6

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intelligenc ...

"asset".

World War I

With war clouds closing in, the project of writing a play together with Conrad based on the latter's novel, ''

With war clouds closing in, the project of writing a play together with Conrad based on the latter's novel, ''Nostromo

''Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard'' is a 1904 novel by Joseph Conrad, set in the fictitious South American republic of "Costaguana". It was originally published serially in monthly instalments of '' T.P.'s Weekly''.

In 1998, the Modern Libra ...

'', had to be abandoned as both men hurriedly left Austria-Hungary. Retinger would have been eligible for military call-up in Galicia (no mention of this is made by his biographers).

He put aside literary endeavours and once more assumed the role of a political lobbyist for Poland, publishing pamphlets and travelling between London, Paris, and New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, aided by Conrad in London. In the first years of the war, this was not on the agenda of the major powers.

Retinger looked instead for other potential alliances and political leverage, which led to meetings with leading Zionists

Zionism is an ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the Jewish people, pursued through the colonization of Palestine, a region roughly cor ...

of the time, including Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( ; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born Israeli statesman, biochemist, and Zionist leader who served as president of the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organization and later as the first pre ...

, Vladimir Zhabotinski, and Nahum Sokolow

Nahum ben Joseph Samuel Sokolow ( ''Nachum ben Yosef Shmuel Soqolov'', ; 10 January 1859 – 17 May 1936) was a Jewish-Polish people, Polish writer, translator, and journalist, the fifth President of the World Zionist Organization, editor of ''H ...

, who were seeking international recognition and rights for the Jewish diaspora

The Jewish diaspora ( ), alternatively the dispersion ( ) or the exile ( ; ), consists of Jews who reside outside of the Land of Israel. Historically, it refers to the expansive scattering of the Israelites out of their homeland in the Southe ...

.

In 1916, guided by Zamoyski and with the approval of H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

, and Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who was Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A physician turned journalist, he played a central role in the poli ...

with his old Parisian connections, Sixtus and Xavier de Bourbon Parme, the Duchess of Montebello and Marquis Boni de Castellane

Marie Ernest Paul Boniface de Castellane, Marquis de Castellane (14 February 1867 – 20 October 1932), known as Boni de Castellane, was a French nobleman and politician. He was known as a leading ''Belle Époque'' tastemaker and the first husban ...

, as well as Zamoyski's friend the Polish General of the Jesuits, Włodzimierz Ledóchowski, Retinger became a "courier" in the secretive European dynastic negotiation suing for peace with Austria. It became known as the ''Sixtus Affair

The Sixtus Affair (, ) was a failed attempt by Emperor Charles I of Austria to conclude a negotiated peace with the allies in World War I. The affair was named after his brother-in-law and intermediary, Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma.

Affair

...

'' and was a failure, due to Germany's refusal to cooperate, thus making Austria more dependent on Germany.

In 1917 Retinger met Arthur "Boy" Capel, the half-French dilettante, polo player, and "sponsor" of Coco Chanel

Gabrielle Bonheur "Coco" Chanel ( , ; 19 August 1883 – 10 January 1971) was a French fashion designer and Businessperson, businesswoman. The founder and namesake of the Chanel brand, she was credited in the post-World War I era with populari ...

. Capel is said to have planted in Retinger's mind the idea of a world federal government based on an Anglo-French alliance.

After concerns for his personal safety due to his "political meddling" in Austria-Hungary and in the emergent Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, in 1918 Retinger was banned from France, and for several months sought sanctuary in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

.

Mexican years

Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

and then to Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, where he became an unofficial political adviser to union organizer Luis Morones, whom he had fortuitously met crossing the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

, and to President Plutarco Elías Calles

Plutarco Elías Calles (born Francisco Plutarco Elías Campuzano; 25 September 1877 – 19 October 1945) was a Mexican politician and military officer who served as the 47th President of Mexico from 1924 to 1928. After the assassination of Ál ...

.

A glimpse of Retinger, newly divorced and lovelorn for the American journalist Jane Anderson, appears in the biography of another American woman, the communist sympathiser Katherine Anne Porter

Katherine Anne Porter (May 15, 1890 – September 18, 1980) was an American journalist, essayist, short story writer, novelist, poet, and political activist. Her 1962 novel '' Ship of Fools'' was the best-selling novel in the United States that y ...

, a member of the Morones circle. In it he is described as a "Polish intriguer" and "British Marxist". In 1921, while on an obscure mission to the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

to buy saddles, Retinger was arrested and imprisoned in Laredo, and Porter was dispatched from Mexico to get him released. That same year Retinger had proposed that Katherine Porter and her friend Mary Doherty accompany him to Europe to do "collaborative work", an offer that was spurned.

Retinger helped advance Mexico's nationalization of its oil industry in 1928. Ethridge's full review is on pp. 94–95 His activities in Mexico lasted almost seven years and only ended with Calles' fall from power in 1936. They inspired Retinger to write three volumes on the tumultuous events in that Latin American republic. The Mexican years were punctuated by trips back to Europe, where he took on the role of representative in the United Kingdom of the Polish Socialist Party (1924–1928).

In 1926 he married his second wife, Stella, with whom he travelled to Mexico on one occasion. After her death in 1933 his two daughters were left in the care of their maternal grandmother and were estranged from him until the 1950s.

In the rest of the interwar period, he published many contributions in periodicals such as the Polish ''Wiadomości Literackie'' (Literary News), on literary and political subjects.

Building blocks on the table

During World War II, Retinger, who was inLondon

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, was involved in arranging for Polish troops to be evacuated to Britain from France. He was asked by Winston Churchill personally to escort Władysław Sikorski

Władysław Eugeniusz Sikorski (; 20 May 18814 July 1943) was a Polish military and political leader.

Before World War I, Sikorski established and participated in several underground organizations that promoted the cause of Polish independenc ...

by plane to England from France, which had just capitulated to the invading Germans.

Retinger became principal adviser and confidant to the Prime Minister of the Polish Government-in-Exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile (), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent Occupation ...

now established in London. Their political relationship actually went back to 1916 and had been strengthened during Sikorski

Sikorski (feminine: Sikorska, plural: Sikorscy) is a Polish-language surname. It belongs to several noble Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth families, see . Variants (via other languages) include Sikorsky, Sikorskyi, Sikorskiy, and Shikorsky.

The ...

's earlier brief stint as prime minister, 1922–23, in newly independent Poland.

Sikorski's dependence on Retinger was the greater as Sikorski had no mastery of the English language

English is a West Germanic language that developed in early medieval England and has since become a English as a lingua franca, global lingua franca. The namesake of the language is the Angles (tribe), Angles, one of the Germanic peoples th ...

. Retinger was dispatched to talk with other exiled government representatives in London, who included Marcel-Henri Jaspar, Paul Van Zeeland

Paul Guillaume, Viscount van Zeeland (11 November 1893 – 22 September 1973) was a Belgian lawyer, economist, Catholic politician and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Belgium from 1935 to 1937.

Biography

van Zeeland was born in Soi ...

, and Paul-Henri Spaak

Paul-Henri Charles Spaak (; 25 January 1899 – 31 July 1972) was an influential Belgian Socialist politician, diplomat and statesman who thrice served as the prime minister of Belgium and later as the second secretary general of NATO. Nicknam ...

, in preparation for a postwar geopolitical landscape. He went on to posit a "Sikorski Plan" consisting of two stages, the first of which was signed in January 1942 and proposed a Polish-Czech confederation. The idea was to expand it into a Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

an confederation with Poland and Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

, Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

as its nucleus around which would be grouped Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, Yugoslavia, and Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

. The agenda behind this was to create a common political blueprint for smaller countries abutting larger European powers and became the basis of a Belgian-Dutch union which would mirror the Polish-Czech arrangement.

This scheme of Retinger's caused problems between London and Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

. In order not to tread on Soviet toes, the British altered their position and refused to back Sikorski's negotiations with the eight smaller European states. In his speech on the Council of Europe, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

br>BBC radio broadcaston 21 March 1943 referred to the necessity of smaller nations forming groupings, but that it was too early to go into detail. The most Retinger was able to achieve was to push through the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement, signed on 30 July 1941, which provided for the formation of the Anders' army, thus ridding Stalin of the immediate human problem posed by the hundreds of thousands of Polish

POW

POW is "prisoner of war", a person, whether civilian or combatant, who is held in custody by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict.

POW or pow may also refer to:

Music

* P.O.W (Bullet for My Valentine song), "P.O.W" (Bull ...

s and deportees from the Soviet occupied Kresy

Eastern Borderlands (), often simply Borderlands (, ) was a historical region of the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic. The term was coined during the interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural and extensively multi-ethnic with ...

regions of the former Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 7 October 1918 and 6 October 1939. The state was established in the final stage of World War I ...

, who after an arduous odyssey across thousands of miles would eventually end up as the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

's human problem. This trade-off foreshadowed the Tehran

Tehran (; , ''Tehrân'') is the capital and largest city of Iran. It is the capital of Tehran province, and the administrative center for Tehran County and its Central District (Tehran County), Central District. With a population of around 9. ...

and Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (), held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the postwar reorganization of Germany and Europe. The three sta ...

s.

Brushes with death

Retinger just avoided perishing atGibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

with Władysław Sikorski

Władysław Eugeniusz Sikorski (; 20 May 18814 July 1943) was a Polish military and political leader.

Before World War I, Sikorski established and participated in several underground organizations that promoted the cause of Polish independenc ...

, in July 1943, when he was not needed in the Premier's Near East troop inspection and was thought better employed in London. The spare seat on the plane went to Sikorski's daughter, who died with her father.

Retinger was devastated by this turn of events. His relations with Sikorski's successor, Stanislaw Mikolajczyk, were much more ambivalent, but he obtained the latter's consent to go on a special SOE mission to Poland in April 1944.

With an SOE brief and without prior training, Retinger, aged 56, parachuted into German-occupied Poland with 2nd Lt. Tadeusz Chciuk-Celt in Operation Salamander to meet with Polish underground figures, to deliver money to the Polish underground, and to "explain to his fellow Poles in the homeland 'how we are going to lose this war'". Following at least one assassination attempt on him, Retinger expressed his frustration:

The latter reference was to elements in the Polish underground

The latter reference was to elements in the Polish underground Home Army

The Home Army (, ; abbreviated AK) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) established in the ...

who were convinced Retinger was not acting in the interests of his country and should therefore be "removed". One apparent attempt to liquidate him was allegedly based on a "death sentence" sanctioned by General Kazimierz Sosnkowski

General Kazimierz Sosnkowski (; 19 November 1885 – 11 October 1969) was a Polish independence fighter, general, diplomat, and architect.

He was a major political figure and an accomplished commander, notable in particular for his contribu ...

. It was foiled by the intervention of an old friend and Home Army member, Tadeusz Gebethner. During his visit in Poland, there was also a failed attempt to kill him with poison.

On return to London, he spent some time in the Dorchester Hotel

The Dorchester is a five-star hotel located on Park Lane and Deanery Street in London, to the east of Hyde Park. It is one of the world's most prestigious hotels. The Dorchester opened on 18 April 1931, and it still retains its 1930s furnis ...

in London's Park Lane

Park Lane is a dual carriageway road in the City of Westminster in Central London. It is part of the London Inner Ring Road and runs from Hyde Park Corner in the south to Marble Arch in the north. It separates Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park to ...

, recovering from his trip ordeal, which left him lame in one leg for the rest of his life, possibly due to polyneuritis brought on by the poison. His first visitor at the Dorchester was Foreign Secretary Sir Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achi ...

.

Immediately after the war, in 1945–46, Retinger travelled to Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

with emergency aid for the capital's population. It consisted largely of tons of British and US army surplus, such as equipment, blankets, and field kitchens. When his erstwhile military escort from Operation Salamander, Tadeusz Chciuk, and his new wife Ewa were arrested as subversives by the Polish communist security service, Retinger allegedly appealed to Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov (; – 8 November 1986) was a Soviet politician, diplomat, and revolutionary who was a leading figure in the government of the Soviet Union from the 1920s to the 1950s, as one of Joseph Stalin's closest allies. ...

in Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

to have them released. Apparently the personal intervention succeeded. In 1948 the Chciuks became refugees in Germany.

Unwanted intrusion

Dark days followed World War II when tensions rose between former Western and Eastern allies and in April 1946 Retinger's flat inBayswater

Bayswater is an area in the City of Westminster in West London. It is a built-up district with a population density of 17,500 per square kilometre, and is located between Kensington Gardens to the south, Paddington to the north-east, and ...

, West London, was broken into and his and his secretary's files ransacked by persons unknown. He reported the matter to Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's London boroughs, 32 boroughs. Its name derives from the location of the original ...

, but the Metropolitan Police were not overly bothered. Retinger escalated his complaint and ended up being interviewed by the British security services. His view was that the newly established communist embassy of the Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's Republic (1952–1989), formerly the Republic of Poland (1947–1952), and also often simply known as Poland, was a country in Central Europe that existed as the predecessor of the modern-day democratic Republic of Poland. ...

was responsible for the break-in.

From the moment that Churchill made his "Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were countries connected to the So ...

" speech in Fulton, Missouri, in April 1946, Retinger turned his efforts to a modified European project he had harboured for decades.

Vision for Europe

After World War II, Retinger feared another devastating war in Europe, this time fought between "Russia" and "the Anglo-Saxons". He became a leading advocate of European unification as a means of securing peace. He helped found both the

After World War II, Retinger feared another devastating war in Europe, this time fought between "Russia" and "the Anglo-Saxons". He became a leading advocate of European unification as a means of securing peace. He helped found both the European Movement

The European Movement International is a lobbying association that coordinates the efforts of associations and national councils with the goal of promoting European integration, and disseminating information about it.

History

Initially the Euro ...

and the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; , CdE) is an international organisation with the goal of upholding human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it is Europe's oldest intergovernmental organisation, represe ...

, somewhat to the dismay of the philosopher Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi, the post-World War I anti-bolshevist founder of the Paneuropean Union

The International Paneuropean Union, also referred to as the Pan-European Movement and the Pan-Europa Movement, is an international organisation and the oldest European unification movement. It began with the publishing of Richard von Coudenh ...

movement.

Retinger, with his connections in Holland, Belgium, and Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

(he was a friend of Denis de Rougemont

Denys Louis de Rougemont (September 8, 1906 – December 6, 1985), known as Denis de Rougemont (), was a Swiss writer and cultural theorist who wrote in French. One of the non-conformists of the 1930s, he addressed the perils of totalitaria ...

), took his cue from Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

's 1946 Zürich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

speech and found fertile ground with thirteen British Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

members of Parliament who backed the idea of a loose European association of states. Retinger was the driving force in the creation of the European League for Economic Cooperation The European League for Economic Cooperation or ELEC (, LECE) is an independent political advocacy group which advocates for closer European integration.

Established in 1946, ELEC was one of the founding members of the European Movement in 1948. It ...

(initially called the Independent League of Economic Cooperation).

He subsequently approached Duncan Sandys

Duncan Edwin Duncan-Sandys, Baron Duncan-Sandys (; 24 January 1908 – 26 November 1987), was a British politician and minister in successive Conservative governments in the 1950s and 1960s. He was a son-in-law of Winston Churchill and played a ...

, Churchill's son-in-law and chairman of the United Europe Movement, about improving cooperation among the various organisations pursuing European unity. They agreed to organise a small meeting of their two organisations with the Nouvelle Equipes Internationales and the European Union of Federalists. This was held in Paris on 20 July 1947, when it was agreed to establish the Committee for the Coordination of the International Movements for European Unity. In December 1947 this was renamed the International Committee of the Movements for European Unity, with Sandys as Executive Chairman and Retinger as its Honorary Secretary.

They organised the 1948 Hague Congress which brought together the two camps of those for a unified Europe and those in favour of a federal Europe.

During the congress, Retinger networked assiduously among the delegates, who included the Vatican diplomat Giovanni Montini, future Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI (born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 until his death on 6 August 1978. Succeeding John XXII ...

. Ensuing discussions led eventually to the formation in 1951 of a European Coal and Steel Community

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was a European organization created after World War II to integrate Europe's coal and steel industries into a single common market based on the principle of supranationalism which would be governe ...

.

Creator of Bilderberg

Retinger was the initiator and architect of the informal Bilderberg conferences in 1952-54 and was their permanent secretary until his premature death in London in 1960. The original group which met in the eponymous Dutch hotel in 1954 was gathered by Retinger and includedDavid Rockefeller

David Rockefeller (June 12, 1915 – March 20, 2017) was an American economist and investment banker who served as chairman and chief executive of Chase Bank, Chase Manhattan Corporation. He was the oldest living member of the third generation of ...

, Denis Healey

Denis Winston Healey, Baron Healey (30 August 1917 – 3 October 2015) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1974 to 1979 and as Secretary of State for Defence from 1964 to 1970; he remains the lo ...

with Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands

Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld (later Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands; 29 June 1911 – 1 December 2004) was Prince of the Netherlands from 6 September 1948 to 30 April 1980 as the husband of Queen Juliana. They had four daughters to ...

, as chairman. The purpose was to stimulate understanding between Europe and the US as the Cold War developed by bringing together financiers, industrialists, politicians and opinion formers. All discussions were to be strictly under Chatham House Rule

Under the Chatham House Rule, anyone who comes to a meeting is free to use information from the discussion, but is not allowed to reveal who made any particular comment. It is designed to increase openness of discussion. The rule is a system for ...

s. A founding member of the group, later British Labour Foreign Secretary, Healey, described the secretive Bilderberg meetings as the "brainchild" of Retinger.

Despite eschewing any distinctions or medals throughout his life, in 1958 he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. He died in poverty of lung cancer. He was buried at North Sheen Cemetery in the presence of five British cabinet ministers as well as of his two younger daughters who were finally reconciled with him. According to the oration of Sir Edward Beddington-Behrens, Retinger not only had special access to 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street in London is the official residence and office of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, prime minister of the United Kingdom. Colloquially known as Number 10, the building is located in Downing Street, off Whitehall in th ...

but also to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

.

Retinger's long-time personal assistant and the editor of his posthumous memoirs, John Pomian, actually , was another Polish émigré in London, later a director of the Heim gallery in London's St James's

St James's is a district of Westminster, and a central district in the City of Westminster, London, forming part of the West End of London, West End. The area was once part of the northwestern gardens and parks of St. James's Palace and much of ...

, owned by the influential Polish art historian and philanthropist, Andrzej Ciechanowiecki.

Personal life

Retinger married twice. In 1912 he wed the well-born Otolia Zubrzycka (divorced 1921, died 1984), with whom he had a daughter, Malina (later Puchalska). In 1926 he wed Stella Morel (died 1933) – daughter of French-born pacifist andDundee

Dundee (; ; or , ) is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, fourth-largest city in Scotland. The mid-year population estimate for the locality was . It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firt ...

member of Parliament, E.D. Morel, and Mary, née Richardson – with whom he had two daughters, Marya (later Fforde) and Stasia (later French). Among his grandchildren are David French – translator into English of Andrzej Sapkowski's '' Witcher Saga'' – and fantasy novelist Jasper Fforde

Jasper Fforde (born 11 January 1961) is an English novelist whose first novel, '' The Eyre Affair'', was published in 2001. He is known mainly for his '' Thursday Next'' novels, but has also published two books in the loosely connected '' Nurser ...

.

During World War I and after, Retinger appears to have fallen under the spell of several women, especially the American journalist Jane Anderson, a supposed lover of Joseph Conrad. Retinger's own liaison with Anderson brought about the breakdown of Retinger's marriage to Otolia and drove a wedge between him and his friend Conrad. However, Conrad biographer John Stape gives an alternative version for the cooling of relations between the two men, suggesting that as Retinger's enthusiasms were not shared by the novelist, shortly after the war – without Retinger's charming wife Otolia by his side – Retinger's proneness to exaggeration and tactlessness made him less socially acceptable.

Controversy

Over the decades since his 1960 death, the left-leaning Retinger continues to draw fascination and controversy with his political skill, his apparently selfless single-mindedness, and his lasting institutional legacy in Europe and beyond. Adam Pragier, a notable Polish exile and trenchant political commentator (and a secondary-school contemporary of Retinger's), has described him as "a sort of adventurer, but in the good sense of the word". On the other hand, detractors impugn his influence due to alleged connections, with deeply secret and malign factions, for which there is so far no reliable evidence. He remains an enigma, and probably the one substantial contributor to post-war European peace who has no physical monument. In 2000 ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

s Ambrose Evans-Pritchard revealed, from declassified US Government records, that:

This revelation touching on Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

circumstances was subsequently analysed in greater detail in 2003 by ''Le Figaro

() is a French daily morning newspaper founded in 1826. It was named after Figaro, a character in several plays by polymath Pierre Beaumarchais, Beaumarchais (1732–1799): ''Le Barbier de Séville'', ''The Guilty Mother, La Mère coupable'', ...

'' commentator . However, as professor Hugh Wilford shows, the initiative to win American backing for a "United States of Europe" came neither from Allen Dulles

Allen Welsh Dulles ( ; April 7, 1893 – January 29, 1969) was an American lawyer who was the first civilian director of central intelligence (DCI), and its longest serving director. As head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the ea ...

, deputy chief, then chief of the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

, nor from Senator William Fulbright

James William Fulbright (April 9, 1905 – February 9, 1995) was an American politician, academic, and statesman who represented Arkansas in the United States Senate from 1945 until his resignation in 1974. , Fulbright is the longest-serving chair ...

, chairman of the American Committee on United Europe, but from European lobbyists of disparate motivation, namely Coudenhove-Kalergi and Retinger, the latter eclipsing the former due to Retinger's close connection with Winston Churchill on European matters.

Retinger's plan was that the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

should be integral to political and economic support for a war-damaged Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

. As "head of casting" for his project, he set about finding key Americans to collaborate with him, among them Charles Douglas Jackson

Charles Douglas (C. D.) Jackson (March 16, 1902 – September 18, 1964) was a United States government psychological warfare advisor and senior executive of Time Inc. As an expert on psychological warfare he served in the Office of War Information ...

, Time-Life

Time Life, Inc. (also habitually represented with a hyphen as Time-Life, Inc., even by the company itself) was an American multi-media conglomerate company formerly known as a prolific production/publishing company and Direct marketing, direct ...

publisher in the 1940s and one-time head of propaganda at the Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

White House.

Retinger has inspired disparate opinions. He was a figure whose allegiances, like his roots, remain obscure and whose accounts of himself varied according to his audience, thus undercutting his reliability – as reflected in various Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the Eng ...

biographies and numerous other sources, including the considered, annotated review, by Norbert Wójtowicz of Poland's Institute of National Remembrance

The Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation (, abbreviated IPN) is a Polish state research institute in charge of education and archives which also includes two public prosecutio ...

, of Marek Celt's 2006 posthumously published ''Z Retingerem do Warszawy i z powrotem. Raport z podziemia 1944'', 'To Warsaw with Retinger and Back. A Report from the Underground 1944''edited by Wojciech Frazik. The disparity in views on Retinger, despite the perception of some personality flaws, does not alter Retinger's mature postwar European legacy.

Selected works

By J. H. Retinger: * * * available at University of Leeds Library * * * * * * * * * * * About Retinger: * * * * . * * * * * * *See also

*European Movement

The European Movement International is a lobbying association that coordinates the efforts of associations and national councils with the goal of promoting European integration, and disseminating information about it.

History

Initially the Euro ...

* European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

* List of governments in exile during World War II

Many countries established governments in exile during World War II. The Second World War caused many governments to lose sovereignty as their territories came under occupation by enemy powers. Governments in exile sympathetic to the Allied or ...

* List of Poles

This is a partial list of notable Polish people, Polish or Polish language, Polish-speaking or -writing people. People of partial Polish heritage have their respective ancestries credited.

Physics

*Miedziak Antal

* Czesław Białobrzesk ...

: Politics, Diplomacy

Notes

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Illustrated biography of Jozef Retinger assembled by Jan Chciuk-Celt

Polish Soviet Relations During The Second World War

photographs held by the

Imperial War Museum

The Imperial War Museum (IWM), currently branded "Imperial War Museums", is a British national museum. It is headquartered in London, with five branches in England. Founded as the Imperial War Museum in 1917, it was intended to record the civ ...

with Józef Retinger (extreme left) at the signing of the Sikorski-Maiski agreement at the FO on 30.07.1941

Photograph of Retinger flanking Churchill at the Hague 1948, on Retinger's grandson's website

* ttp://bilderbergmeetings.co.uk/jozef-retinger/ Bilderberg website on Retinger's life in brief {{DEFAULTSORT:Retinger, Jozef 1888 births 1960 deaths Ambassadors of Poland to the Soviet Union Council of Europe people Members of the Steering Committee of the Bilderberg Group Polish politicians University of Paris alumni Alumni of the University of London Polish Freemasons European integration pioneers Geopoliticians Polish emigrants to the United Kingdom Polish diplomats Polish spies MI6 personnel Special Operations Executive personnel 20th-century Polish writers Exophonic writers Polish essayists Polish male essayists Polish political writers Polish people of World War II History of the European Union Polish people of Jewish descent Polish people of Rusyn descent Burials at North Sheen Cemetery