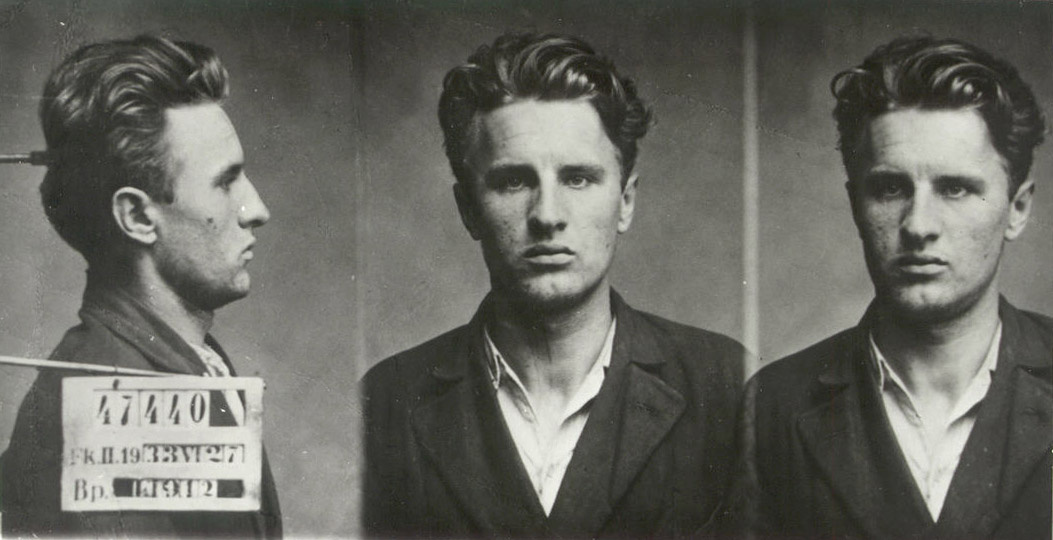

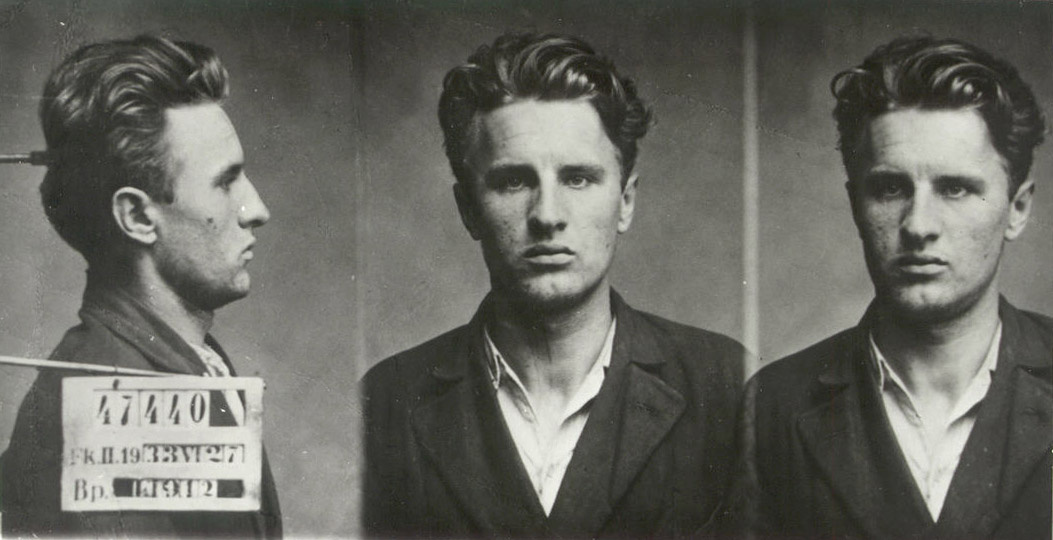

János Kádár (fototeca on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

János József Kádár (; ; 26 May 1912 – 6 July 1989), born János József Czermanik, was a Hungarian communist leader and the General Secretary of the

Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party

The Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party ( hu, Magyar Szocialista Munkáspárt, MSZMP) was the ruling Marxist–Leninist party of the Hungarian People's Republic between 1956 and 1989. It was organised from elements of the Hungarian Working P ...

, a position he held for 32 years. Declining health led to his retirement in 1988, and he died in 1989 after being hospitalized for pneumonia.

Kádár was born in Fiume

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Primorj ...

in poverty to a single mother. After living in the countryside for some years, Kádár and his mother moved to Budapest. He joined the Party of Communists in Hungary

The Hungarian Communist Party ( hu, Magyar Kommunista Párt, abbr. MKP), known earlier as the Party of Communists in Hungary ( hu, Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja, abbr. KMP), was a communist party in Hungary that existed during the interwar ...

's youth organization, KIMSZ, and went on to become a prominent figure in the pre-1939 Communist Party, eventually becoming First Secretary. As a leader, he would dissolve the party and reorganize it as the Peace Party, but the new party failed to win much popular support.

After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, with Soviet support, the Communist Party took power in Hungary. Kádár rose through the Party ranks, serving as Interior Minister

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergenc ...

from 1948 to 1950. In 1951 he was imprisoned by the government of Mátyás Rákosi

Mátyás Rákosi (; born Mátyás Rosenfeld; 9 March 1892

– 5 February 1971) was a Hungarian but was released in 1954 by reformist Prime Minister

After being released for

After being released for

– 5 February 1971) was a Hungarian but was released in 1954 by reformist Prime Minister

Imre Nagy

Imre Nagy (; 7 June 1896 – 16 June 1958) was a Hungarian communist politician who served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers (''de facto'' Prime Minister) of the Hungarian People's Republic from 1953 to 1955. In 1956 Nagy became leader ...

. On 25 October 1956, during the Hungarian Revolution, Kádár replaced Ernő Gerő

Ernő Gerő (; born Ernő Singer; 8 July 1898 – 12 March 1980) was a Hungarian Communist leader in the period after World War II and briefly in 1956 the most powerful man in Hungary as the second secretary of its ruling communist party.

Ear ...

as General Secretary of the Party, taking part in Nagy's revolutionary government. However, a week later he would break with Nagy over his decision to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

. After the Soviet intervention, Kádár was selected to lead the country. He presided through repression, ordering the execution of Nagy and his close associates and the imprisonment of many others. He would gradually moderate, releasing the remaining prisoners of this period in 1963.

As the leader of Hungary, Kádár attempted to liberalize the Hungarian economy with a greater focus on consumer goods, in what would become known as Goulash Communism

Goulash Communism ( hu, gulyáskommunizmus), also commonly called Kádárism or the Hungarian Thaw, is the variety of socialism in Hungary following the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. János Kádár and the Hungarian People's Republic imposed polic ...

. As a result of the relatively high standard of living, fewer human rights cases of abuse, and more relaxed travel restrictions than those present in other Eastern Bloc countries, Hungary was considered the most livable country in the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War. Kádár was succeeded by Károly Grósz

Károly Grósz (1 August 1930 – 7 January 1996) was a Hungarian communist politician, who served as the General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party from 1988 to 1989.

Early career

Grósz was born in Miskolc, Hungary. He joi ...

as General Secretary on 22 May 1988. Grósz would only serve a year in this post due to the fall of communism in Europe in 1989.

While at the head of Hungary, Kádár pushed for an improvement in standards of living. Kádár increased international trade

International trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories because there is a need or want of goods or services. (see: World economy)

In most countries, such trade represents a significan ...

with non-communist countries, in particular those of Western Europe. Kádár's policies differed from those of other communist leaders such as Nicolae Ceaușescu

Nicolae Ceaușescu ( , ; – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian communist politician and dictator. He was the general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 to 1989, and the second and last Communist leader of Romania. He w ...

, Enver Hoxha

Enver Halil Hoxha ( , ; 16 October 190811 April 1985) was an Albanian communist politician who was the authoritarian ruler of Albania from 1944 until his death in 1985. He was First Secretary of the Party of Labour of Albania from 1941 unt ...

, and Wojciech Jaruzelski

Wojciech Witold Jaruzelski (; 6 July 1923 – 25 May 2014) was a Polish military officer, politician and ''de facto'' leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1981 until 1989. He was the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party be ...

, all of whom favored more orthodox interpretations of Marxism-Leninism. Kádár's reformist policies would in turn be viewed with distrust by the conservative leadership of Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and ...

in the Soviet Union. Kádár's legacy remains disputed. However, nostalgia for the Kádár era remains widespread in Hungary. A 2020 poll carried out by policy solutions found that 54 percent of people believe that most had a better life under Kádár, as opposed to 31 percent who disagree with that assertion.

Childhood

Kádár was born out of wedlock in Fiume (now:Rijeka

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Prim ...

, Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

) on 26 May 1912.Gough 2006, p. 2. The infant was registered in the Italian version of his name: Giovanni Giuseppe Czermanik (In Hungarian: János József Czermanik) because he was born in the Italian established Santo Spirito Hospital. He got the Csermanek family name of his mother. He was an illegitimate son of the soldier János Krezinger and the servant maid Borbála Czermanik. Krezinger came from a smallholder

A smallholding or smallholder is a small farm operating under a small-scale agriculture model. Definitions vary widely for what constitutes a smallholder or small-scale farm, including factors such as size, food production technique or technology ...

family of Pusztaszemes, Somogy County

Somogy ( hu, Somogy megye, ; hr, Šomođska županija; sl, Šomodska županija, german: Komitat Schomodei) is an administrative county (comitatus or ''megye'') in present Hungary, and also in the former Kingdom of Hungary.

Somogy County lies ...

. Kádár's father had Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

n German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

origin. The mother, Borbála Csermanek was born in Ógyalla (today Hurbanovo

Hurbanovo (until 1948 ''Stará Ďala'', hu, Ógyalla, german: Altdala) is a town and large municipality in the Komárno District in the Nitra Region of south-west Slovakia. In 1948, its Slovak name was changed to Hurbanovo, named after Slovak wri ...

, Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

) to a landless Slovak father and Hungarian mother.Gough 2006, p. 1. The parents of Borbála were too poor to provide schooling for the girl, thus the teenager girl had to work as maid in various villas. Soon Borbála got a job in the popular seaside resort town, Opatija

Opatija (; it, Abbazia; german: Sankt Jakobi) is a town and a municipality in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County in western Croatia. The traditional seaside resort on the Kvarner Gulf is known for its Mediterranean climate and its historic buildings re ...

. Krezinger met with Borbála during his military service

Military service is service by an individual or group in an army or other militia, air forces, and naval forces, whether as a chosen job ( volunteer) or as a result of an involuntary draft ( conscription).

Some nations (e.g., Mexico) requ ...

in Opatija, the story however how they met is unknown. Abandoned, Borbála gave birth to János in the middle of the holiday season

The Christmas season or the festive season (also known in some countries as the holiday season or the holidays) is an annually recurring period recognized in many Western and other countries that is generally considered to run from late November ...

, no one wanted to employ a single mother with a child. His mother, Borbála went to look for Krezinger, but his family wanted nothing to do with them. She walked ten kilometres to the city of Kapoly where she persuaded the Bálint family to care for her child for a fee. Borbála found work in Budapest.Gough 2006, p. 3. To avoid the pronunciation problems of the Slovak-origin Czermanik name in Budapest, the family changed the orthography of their name to Csermanek.

Kádár's foster father, Imre Bálint was in charge. But it was Bálint's brother, Sándor Bálint, Kádár would remember as his "true" foster father. While Imre served in the army during World War I, Sándor was left to take care of Kádár. Sándor was the only man Kádár had a good relationship with throughout his early childhood. Kádár started working at an early age and helped Sándor take care of his sick wife. Kádár years later recalled how his early experiences moved him towards Marxist-Leninism. He recalls how he was accused of setting a building on fire when the true culprit was the corrupt inspector's son. Suddenly in 1918, at the age of six, Borbála reclaimed him, moved him to Budapest and enrolled him in school. In school he got bullied for his bumpkin manners and his peasant talk.Gough 2006, pp. 3–4.

Borbála worked hard to ensure that Kádár would get a good education. In the summer time, Kádár would find work in the countryside. He was seen as "alien" by his contemporaries, in the countryside they would call him a "city boy" while in the city they would call him a "country boy". Then in 1920, Borbála got pregnant again; the father left soon. Kádár helped take care of his half-brother, Jenő.Gough 2006, pp. 6–7. At the Cukor Street Elementary School, Kádár proved to be a bright student. He skipped school often, and his mother tried beatings to make it stop. Classes were easy for him and he skipped school to play sports. He did read often however, but his mother was unimpressed by this and sarcastically asked him if he was a "gentleman of leisure". Kádár left school at the age of fourteen in 1926. Kádár started his apprenticeship as a car mechanic. After he was turned down as a car mechnic, he started work as an apprentice of Sándor Izsák, chief Hungarian representative of Torpedo Typewriter Company in the autumn of 1927. Typewriter mechanics had a high standing among the working class, there were only 160 of them in the country.

Party work

His first meeting with Marxist literature came in 1928 after he won a junior chess competition organised by the Barbers Trade Union. His prize wasFriedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' Anti-Dühring ''Anti-Dühring'' (german: Herrn Eugen Dührings Umwälzung der Wissenschaft, "Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science") is a book by Friedrich Engels, first published in German in 1878. It had previously been serialised in the newspaper '' ...

''. The tournament organiser explained to Kádár that if he didn't understand it after his first reading, he should re-read it until he understood it. Kádár followed his advice, even if his friends were "unimpressed" by his reading. As he later noted later in his life, he did not understand the reading but it got him thinking: "Immutable laws and connections in the world which I had not suspected." While it may be true that as Kádár comments that the book had great influence over him, it was in 1929 when he was fired after he flared up at his employer after he talked condescendingly towards Kádár. When the Great Depression hit Hungary, Kádár was the first to be fired. What ensued was low paid jobs and poverty. He later became unemployed, and it was this experience which brought him into contact with the Communist Party of Hungary. According to Kádár he became a member of the party in 1931.Gough 2006, p. 11.

In September 1930, Kádár took part in an organised trade union strike. The strike was crushed by the authorities, and many of his fellow communists were arrested. In the aftermath of the failed strike, he supported the party by gathering signatures for candidates of the '' Anti-Dühring ''Anti-Dühring'' (german: Herrn Eugen Dührings Umwälzung der Wissenschaft, "Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science") is a book by Friedrich Engels, first published in German in 1878. It had previously been serialised in the newspaper '' ...

Socialist Workers' Bloc

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

, an attempt by the Communist Party to create a front which would win over new supporters. This attempt was thwarted by the authorities, and new arrests ensued. In June 1931, he joined the communist youth organization, the Communist Young Workers' Association (KIMSZ). He joined the Sverdlov party cell, named after Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

Yakov Sverdlov

Yakov Mikhailovich Sverdlov (russian: Яков Михайлович Свердлов; 3 June O. S. 22 May">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 22 May 1885 – 16 March 1919) was a Bolshev ...

. His alias within the party became János Barna. During his early membership, the party was illegal, following the crushing of the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szocialista Szövetséges Tanácsköztársaság) (due to an early mistranslation, it became widely known as the Hungarian Soviet Republic in English-language sources ( ...

. In December 1931, the authorities had been able to track him down, and Kádár was arrested on charges of spreading communism, and being a communist. He denied the charges, and because of lack of evidence, was released. He was however under constant police surveillance, and after some days, he was back in contact with KIMSZ. He was given new responsibilities, and by May 1933 he became a member of the KIMSZ Budapest committee. Because of his promotion in the communist hierarchy, he was given a new alias, Róna. The party suggested, but Kádár rejected, the offer of studying at the Lenin Institute

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of t ...

in Moscow, claiming that he could not leave his family alone. His advance up the hierarchy came to an end when he was arrested on 21 June 1931 with other communist activists. Kádár cracked because of police brutality

Police brutality is the excessive and unwarranted use of force by law enforcement against an individual or a group. It is an extreme form of police misconduct and is a civil rights violation. Police brutality includes, but is not limited to, ...

, when he later confronted his fellow arrested communists, he realized he had made a mistake and denied and retracted all his confessions. He was sentenced to two years in prison. Because of his confessions to the police, he was suspended from KIMSZ.

After being released for

After being released for parole

Parole (also known as provisional release or supervised release) is a form of early release of a prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by certain behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated parole officers, or ...

, he was politically in limbo

In Catholic theology, Limbo (Latin ''limbus'', edge or boundary, referring to the edge of Hell) is the afterlife condition of those who die in original sin without being assigned to the Hell of the Damned. Medieval theologians of Western Europ ...

. The hope of rejoining the Communist Party was shattered by the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

's decision to dissolve the national communist party in Hungary. The few remaining members of the party were told to infiltrate and work cooperatively with the Social Democratic Party of Hungary

The Social Democratic Party of Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szociáldemokrata Párt, MSZDP) is a social democratic political party in Hungary. Historically, the party was dissolved during the occupation of Hungary by Nazi Germany (1944–1945) ...

and trade unions. Kádár had in the meantime been able to persuade himself that it was because of changes within the party, and not his confessions, which had led to none of his associates making contact with him. He did, at the same time, have four more months of his prison sentence to serve before being released. In prison Kádár met with Mátyás Rákosi

Mátyás Rákosi (; born Mátyás Rosenfeld; 9 March 1892

– 5 February 1971) was a Hungarian , a commissar of the Hungarian Soviet Republic and a renowned political prisoner. While Kádár later claimed that there grew a father-son like bond between them, the more plausible truth is that there grew a "somewhat adolescent cheekiness" between the two. In prison, Rákosi interrogated Kádár, and came to the conclusion that his confessions were due to his "shortcomings". After being released from prison for good, some former party activists made contact with him and instructed Kádár to infiltrate the Social Democratic Party with them. Within the party, Kádár and his associates made no secret of their Marxist views, frequently talking about the struggles of the working class and their gaze, which was directed towards the

– 5 February 1971) was a Hungarian , a commissar of the Hungarian Soviet Republic and a renowned political prisoner. While Kádár later claimed that there grew a father-son like bond between them, the more plausible truth is that there grew a "somewhat adolescent cheekiness" between the two. In prison, Rákosi interrogated Kádár, and came to the conclusion that his confessions were due to his "shortcomings". After being released from prison for good, some former party activists made contact with him and instructed Kádár to infiltrate the Social Democratic Party with them. Within the party, Kádár and his associates made no secret of their Marxist views, frequently talking about the struggles of the working class and their gaze, which was directed towards the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

.

Kádár still lived in poverty, and found it hard to blend in with the upper working class and the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

. Paradoxically, his main Communist contact in the Social Democratic Party was a sculptor named György Goldmann. Kádár evolved into an effective speaker on "bread and butter issues", but failed at having any success on more serious and complex topics. In 1940 he was recalled to the party's ranks. At the beginning of its re-founding, the party liked to use members without any police records

A criminal record, police record, or colloquially RAP sheet (Record of Arrests and Prosecutions) is a record of a person's criminal history. The information included in a criminal record and the existence of a criminal record varies between coun ...

, therefore Kádár was given more responsibilities within the infiltration of the Social Democratic Party. During May and June the police arrested and rounded up several party activists, including Goldman, but Kádár had managed to go into hiding. As early as May 1942, Kádár became a member of the newly formed Central Committee of the Communist Party, mostly due to the lack of personnel, seeing that the majority of them had been sent to prison. István Kovács, the acting party leader from December 1942, said; "he ádárwas extremely modest, a clever man but not then theoretically trained". Kovács brought Kádár into the party leadership and gave him a seat in the Secretariat of the Central Committee. By January 1943, had been able to get in touch with some seventy to eighty members, but this effort was torn apart by a new round of mass arrests, with Kovács being among them.

First Secretaryship

The new leadership after the last mass arrest consisted of Kádár as First Secretary, Gábor Péter,István Szirmai

István () is a Hungarian language equivalent of the name Stephen or Stefan. It may refer to:

People with the given name Nobles, palatines and judges royal

* Stephen I of Hungary (c. 975–1038), last grand prince of the Hungarians and first ki ...

and Pál Tonhauser

Pál is a Hungarian masculine given name, the Hungarian version of Paul (given name), Paul. It may refer to:

* Pál Almásy (1818-1882), Hungarian lawyer and politician

* Pál Bedák (born 1985), Hungarian boxer

* Pal Benko, Pál Benkő (1928–20 ...

. During Kádár's first tenure as leader of the party, he faced many problems, the most important being that the communists were becoming increasingly irrelevant in a fast-changing situation, mostly because of the Hungarian government's continuing interference. In a meeting with Árpád Szakasits

Árpád Szakasits (; 6 December 1888 – 3 May 1965) was a Hungarian Social Democrat, then Communist politician. He served as the country's head of state from 1948 to 1950, the first Communist to hold the post.

A longtime leader of the Hungar ...

, a left-leaning Social Democrat

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote soc ...

, Kádár was asked to stop the party's illegal infiltration of his party. This meeting led to criticism being mounted against him during a Central Committee plenum meeting. In February 1936, Peter came up with an idea; his idea was to dissolve the party so that party members independently could spread communism, while a small secret leadership structure could keep itself together for some years. This, he said, would stop the continuing mass arrest of the communist party personnel and in turn strengthen the party for the future. While at the beginning Kádár was against such an idea, the idea grew on him and came to the conclusion that instead of dissolving the party, he would pretend to dissolve it and rename the party which would effectively throw the Hungarian authorities off their trail. The so-called "new party" was formed in August under the name, Peace Party. This decision was not supported by all, and the Moscow-based Hungarian Communists led by Mátyás Rákosi

Mátyás Rákosi (; born Mátyás Rosenfeld; 9 March 1892

– 5 February 1971) was a Hungarian condemned the decision and domestic militants. Kádár disagreed with the criticism laid against him, claiming it was a "tactical retreat" which led to the renaming of the party, but with no changes to either the party's principles or structures. His attempted plan to fool the police failed, and the police continued arresting Hungarian Communists. Later in his life, this would be one of the few topics of his life Kádár would refuse to discuss. After the German invasion of Hungary, the Peace Party, with other parties, established the

Rákosi was forced to resign in 1956, replaced by Gerő. On 23 October 1956, students marched through Budapest intending to present a petition to the government. The procession swelled as several people poured onto the streets. Gerő replied with a harsh speech that angered the people, and police opened fire. It proved to be the start of the

Rákosi was forced to resign in 1956, replaced by Gerő. On 23 October 1956, students marched through Budapest intending to present a petition to the government. The procession swelled as several people poured onto the streets. Gerő replied with a harsh speech that angered the people, and police opened fire. It proved to be the start of the

Kádár assumed power in a critical situation. The country was under Soviet military administration for several months. The fallen leaders of the Communist Party took refuge in the Soviet Union and were planning to regain power in Hungary. The Chinese, East German, and Czechoslovak leaders demanded severe reprisals against the perpetrators of the "counter-revolution". Despite the distrust surrounding the new leadership and the economic difficulties, Kádár was able to normalize the situation in a remarkably short time. This was due to the realization that, under the circumstances, it was impossible to break away from the Communist bloc. The Hungarian people realized that the promises of the West to help the Hungarian revolution were unfounded and that the logic of the Cold War determined the outcome. Hungary remained part of the Soviet sphere of influence with the tacit agreement of the West. Though influenced strongly by the Soviet Union, Kádár enacted a policy slightly contrary to that of Moscow, for example, allowing considerably large private plots for farmers of

Kádár assumed power in a critical situation. The country was under Soviet military administration for several months. The fallen leaders of the Communist Party took refuge in the Soviet Union and were planning to regain power in Hungary. The Chinese, East German, and Czechoslovak leaders demanded severe reprisals against the perpetrators of the "counter-revolution". Despite the distrust surrounding the new leadership and the economic difficulties, Kádár was able to normalize the situation in a remarkably short time. This was due to the realization that, under the circumstances, it was impossible to break away from the Communist bloc. The Hungarian people realized that the promises of the West to help the Hungarian revolution were unfounded and that the logic of the Cold War determined the outcome. Hungary remained part of the Soviet sphere of influence with the tacit agreement of the West. Though influenced strongly by the Soviet Union, Kádár enacted a policy slightly contrary to that of Moscow, for example, allowing considerably large private plots for farmers of  Starting in the early 1960s, he gradually lifted Rákosi's more draconian measures against free speech and movement, and also eased some restrictions on cultural activities. He even tolerated

Starting in the early 1960s, he gradually lifted Rákosi's more draconian measures against free speech and movement, and also eased some restrictions on cultural activities. He even tolerated  Kádár was awarded the

Kádár was awarded the

On 12 April 1989 Kádár unexpectedly appeared and made a rambling, incoherent speech at the closed meeting of the Central Committee. By the " right of the last word", he wanted to confess about his negotiations in 1956 in Moscow (about which he never spoke publicly) and about the conviction and execution of Imre Nagy. But all the changes that occurred in Eastern Europe and Hungary between 1956 and 1989 were at the same time in his head. An interpretation of Kádár's thoughts was offered by Mihály Kornis, who gave a lecture about János Kádár.

According to

On 12 April 1989 Kádár unexpectedly appeared and made a rambling, incoherent speech at the closed meeting of the Central Committee. By the " right of the last word", he wanted to confess about his negotiations in 1956 in Moscow (about which he never spoke publicly) and about the conviction and execution of Imre Nagy. But all the changes that occurred in Eastern Europe and Hungary between 1956 and 1989 were at the same time in his head. An interpretation of Kádár's thoughts was offered by Mihály Kornis, who gave a lecture about János Kádár.

According to

online

* Niklasson, Tomas. "Regime stability and foreign policy change: interaction between domestic and foreign policy in Hungary 1956-1994" (PhD dissertation Lund University, 2006

online

* Tőkés, Rudolf L. ''Hungary’s Negotiated Revolution: Economic Reform, Social Change and Political Succession, 1957-1990'' (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

János Kádár: Selected Speeches and Interviews

'

Kádár János 1988.05.Kádár János temetése

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kadar, Janos 1912 births 1989 deaths Politicians from Rijeka People from the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia Converts to Roman Catholicism from atheism or agnosticism Hungarian Roman Catholics Hungarian Communist Party politicians Members of the Hungarian Working People's Party Members of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party Prime Ministers of Hungary Hungarian Interior Ministers Members of the National Assembly of Hungary (1945–1947) Members of the National Assembly of Hungary (1947–1949) Members of the National Assembly of Hungary (1949–1953) Members of the National Assembly of Hungary (1953–1958) Collaborators with the Soviet Union People of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 People of the Cold War Hungarian People's Republic Foreign Heroes of the Soviet Union Lenin Peace Prize recipients Grand Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Hungary (civil) Heroes of Socialist Labour Recipients of the Order of Lenin Hungarian prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by Hungary Hungarian people of Slovak descent Hungarian people of German descent Burials at Kerepesi Cemetery Hungarian politicians convicted of crimes Deaths from cancer in Hungary

– 5 February 1971) was a Hungarian condemned the decision and domestic militants. Kádár disagreed with the criticism laid against him, claiming it was a "tactical retreat" which led to the renaming of the party, but with no changes to either the party's principles or structures. His attempted plan to fool the police failed, and the police continued arresting Hungarian Communists. Later in his life, this would be one of the few topics of his life Kádár would refuse to discuss. After the German invasion of Hungary, the Peace Party, with other parties, established the

Hungarian Front Hungarian may refer to:

* Hungary, a country in Central Europe

* Kingdom of Hungary, state of Hungary, existing between 1000 and 1946

* Hungarians, ethnic groups in Hungary

* Hungarian algorithm, a polynomial time algorithm for solving the assignm ...

, the party's potential allies were still very wary of them. Therefore, the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalitio ...

was never able to win much support amongst the populace. In the aftermath of the invasion, the party under Kádár's leadership started partisan operations and created their own Military Committee. Kádár tried to cross the border into Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

in hope of making contact with the Yugoslav partisan

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian language, Macedonian, Slovene language, Slovene: , or the National Liberation Army, sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska (NOV), Народноослободилачка војска (НО� ...

s and their leader, Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his deat ...

. At the same time, Kádár probably hoped to establish better, and stronger, relations with the USSR; something they had been trying to do since 1942. Kádár was given a new identity as an army corporal trying to cross the Hungarian-Yugoslav border. This attempt failed, and he was sentenced to two and a half years in prison. The authorities never figured out his real identity therefore members such as Rákosi thought he was a secret agent for the police. There is however no hard proof for these accusations, and incompetence remains the sole plausible reason. It was later proven, when SS officer Otto Winckelmann reported to Berlin that Kádár had been arrested, they had mistakenly confused Kádár for another communist.Gough 2006, p. 23.

Kádár, while in prison, was able to send out messages to Péter, and other high-ranking party members, they were able to orchestrate a scheme to free him. In the meantime, the leader of Hungary Miklós Horthy

Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya ( hu, Vitéz nagybányai Horthy Miklós; ; English: Nicholas Horthy; german: Nikolaus Horthy Ritter von Nagybánya; 18 June 1868 – 9 February 1957), was a Hungarian admiral and dictator who served as the regen ...

was conspiring against the German occupiers. There were rumours that claim that Horthy tried to get in contact with Kádár, but did not know that he was in prison. Horthy was deposed by the German government and replaced by Arrow Cross Party

The Arrow Cross Party ( hu, Nyilaskeresztes Párt – Hungarista Mozgalom, , abbreviated NYKP) was a far-right Hungarian ultranationalist party led by Ferenc Szálasi, which formed a government in Hungary they named the Government of Nationa ...

leader Ferenc Szálasi

Ferenc Szálasi (; 6 January 1897 – 12 March 1946), the leader of the Arrow Cross Party – Hungarist Movement, became the "Leader of the Nation" (''Nemzetvezető'') as head of state and simultaneously prime minister of the Kingdom of Hungary' ...

. Szálasi's policies had an immediate effect on Kádár; he had emptied the prison Kádár lived in and sent them to Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as concen ...

. Kádár was able to escape and made his way back to Budapest. Immediately after his return to Budapest, Kádár headed the communist party's military committee. The committee tried to persuade workers to help the Soviet forces, but was not able to muster much support from the populace, therefore its effect was marginal at best. After the Soviet victory in Budapest, he changed his name from Csermanek to Kádár, literally meaning "cooper

Cooper, Cooper's, Coopers and similar may refer to:

* Cooper (profession), a maker of wooden casks and other staved vessels

Arts and entertainment

* Cooper (producers), alias of Dutch producers Klubbheads

* Cooper (video game character), in ' ...

" or "barrel-maker".

From leadership to show trials

Post–World War II career

After the Soviet liberation of Hungary, the Soviet–Hungarian Communist leadership sent Zoltán Vas and the new Kremlin-approved Central Committee of the Communist Party of Hungary; Kádár became a member. Kádár rose, not because of ideology, or technical knowledge, but rather for his organisational skills. He helped organize the Party's headquarters and designed its membership card. The Soviet troops stationed in Hungary committedmass rape

Mass sexual assault is the collective sexual assault of individuals in public by a group. Typically acting under the protective cover of large gatherings, victims have reported being groped, stripped, beaten, bitten, penetrated and raped.

Egyp ...

s and pillaged Budapest and the countryside. Kádár told the Interior Minister, "The Soviet command caused really big difficulties in our work, especially in the beginning, and they still do". Kádár was appointed deputy chief of police. He had sharp critics, such as Rákosi's party deputy Ernő Gerő

Ernő Gerő (; born Ernő Singer; 8 July 1898 – 12 March 1980) was a Hungarian Communist leader in the period after World War II and briefly in 1956 the most powerful man in Hungary as the second secretary of its ruling communist party.

Ear ...

who felt his decision to dissolve the party during the war was a rash decision. Other peers felt he had been over-promoted. Nevertheless, he moved up to the Politburo of the Communist Party of Hungary. In February 1945, Rákosi was elected General Secretary of the Communist Party of Hungary.

Rákosi's leadership consisted of Mihály Farkas

Mihály Farkas (born Hermann Lőwy; 18 July 1904 – 6 December 1965) was a Hungarian Communist politician who served as Minister of National Defense of the Hungarian People's Republic.

Biography

He was born in 1904 in Abaújszántó to ...

the Minister of Defence

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

. Kádár and Béla Kovács noted with puzzlement the leadership's total lack of interest in the domestic Communist's experience and outlook. As head of cadres, Kádár supervised membership appointments to the party. This position gave him contacts, some of whom would become very important to him in his later life. After failing to secure a majority in Parliament after the 1945 election, the Communist leadership started the divide and conquer strategy known as salami tactics

Salami slicing tactics, also known as salami slicing, salami tactics, the salami-slice strategy, or salami attacks, is the practice of using a series of many small actions to produce a much larger action or result that would be difficult or unlawf ...

. Kádár became a prominent figure during the period between the 1945 and the 1947 Hungarian parliamentary elections Hungarian may refer to:

* Hungary, a country in Central Europe

* Kingdom of Hungary, state of Hungary, existing between 1000 and 1946

* Hungarians, ethnic groups in Hungary

* Hungarian algorithm, a polynomial time algorithm for solving the assignme ...

. Kádár had evolved a sense of rivalry with the Social Democratic Party of Hungary, claiming the party was "thrashing" them in government, and that they made it impossible for the Communists to negotiate policy with the Hungarian trade unions.Gough 2006, p. 31.

In 1946, Kádár campaigned for the communist party in workers districts and factories. These areas were heavily contested between the Communists and the Social Democrats. The Communists were able to persuade the Social Democrats to hold elections in factories where the communists held the majority. The clear majority results gained by the Communists during this election prompted the Social Democrats to postpone the rest of the election. At the 3rd Congress of the Communist Party of Hungary

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* High ...

, Kádár was appointed one of Rákosi's two deputies. He was appointed deputy because of social and ethnic background, the majority of the leadership were of Jewish origins and were intellectuals, Kádár was however a "Hungarian" worker. In the aftermath of his appointment, he enrolled himself in Russian lessons and grew fond of reading, his favorite being ''The Good Soldier Švejk

''The Good Soldier Švejk'' () is an unfinished satirical dark comedy novel by Czech writer Jaroslav Hašek, published in 1921–1923, about a good-humored, simple-minded, middle-aged man who pretends to be enthusiastic to serve Austria-Hungary ...

''.

Kádár, as in 1946, was a Communist Party campaigner, and was described by historian Robert Gough as "a great success". The Communist Party won a majority in parliament in 1947, and because of the escalation of the Cold War, the Soviet leadership ordered them to create a one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

. Kádár played an active role in the creation of the Hungarian Working People's Party

The Hungarian Working People's Party (, abbr. MDP) was the ruling communist party of Hungary from 1948 to 1956.

It was formed by a merger of the Hungarian Communist Party (MKP) and the Social Democratic Party of Hungary (MSZDP).Neubauer, Joh ...

; created by a merger of the Social Democratic Party and the Communist Party. At the unification congress Kádár made a speech which made little impact on the Communist movement in Hungary. In May 1948 Kádár visited the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, and for the first and last time in his life he saw Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

with his own eyes. During his visit to the USSR, Kádár's brother, Jenő died. On 5 August 1948 László Rajk

László Rajk (8 March 1909 – 15 October 1949) was a Hungarian Communist politician, who served as Minister of Interior and Minister of Foreign Affairs. He was an important organizer of the Hungarian Communists' power (for example, organizi ...

was appointed to the office of the Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between coun ...

, and Kádár took his place as Minister of the Interior. As Interior Minister, he did not have real power as the most important organizations of internal state security operated under the direct control of Rákosi and his closest associates. In 1949, Borbála died, and Kádár married Mária Tamáska.

Just as Stalin had launched a Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

against those with knowledge of the pre-Stalin party, Rákosi launched a purge against those who had worked in Hungary, and not in the Soviet Union, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and before. In retrospect, it is clear that Kádár was appointed Minister of the Interior with the deliberate aim to involve him in the "show trial" of Laszlo Rajk, although the investigations and proceedings were handled by the State Security Agency with the active participation of the Soviet Secret Police. Rákosi later boasted of "spending many a sleepless night" in unraveling the threads of the "anti-party conspiracy" led by Rajk and his "gang." During the public trial, Rákosi personally gave instructions to the judge over the phone. Rákosi would later attempt to blame Kádár for Rajk's death. Later in his life Rákosi said that Rajk died screaming "Long live Stalin! Long live Rákosi!" while Tibor Szönyi Tibor is a masculine given name found throughout Europe.

There are several explanations for the origin of the name:

* from Latin name Tiberius, which means "from Tiber", Tiber being a river in Rome.

* in old Slavic languages, Tibor means "sacred pl ...

died without saying a word and András Szalai crying. Farkas and Gábor Péter, upon the death of Rajk and the others, said "provocateurs to their last breaths". This event didn't assure Kádár; making him doubt if any of the accusation leveled against his coworkers were true. It is believed that after Rajk's death Kádár was seen vomiting; these rumours have not been confirmed by any sources from that time. Rákosi contacted him the following the day, asking him why he was in such a bad mood, and continued, saying; "Did the executions affect you that much?". According to certain rumours, which are probably not reliable, Kádár visited Rákosi to tell him about his reaction to the execution. Later, during a party presentation to a college, Kádár emphasized party austerity. This presentation might reflect on Kádár's reaction to Rajk's execution and his revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on th ...

that he might become the next victim of government repression. When holding his presentation, he was described by his audience as a "haggard", "distressed" and as a man under a lot of "strain".

Show trial and rehabilitation

Rákosi told Kádár, in late August 1950, that formerSocial Democratic

Social democracy is a Political philosophy, political, Social philosophy, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocati ...

party leader Árpád Szakasits

Árpád Szakasits (; 6 December 1888 – 3 May 1965) was a Hungarian Social Democrat, then Communist politician. He served as the country's head of state from 1948 to 1950, the first Communist to hold the post.

A longtime leader of the Hungar ...

had confessed to being a spy for the capitalistic

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

countries. Szakasits' imprisonment would be the start of a long purge against former social democrats, trade union officials, and high-standing communist party members. The purge would last until 1953, the extent of the purge went so far that the ÁVH held files on around one million, literally one-tenth of Hungary's population at that time. The purges were enacted when Rákosi and his associates were in the middle of the country's collectivising agriculture and the rapid industrialisation efforts. Ernő Gerő

Ernő Gerő (; born Ernő Singer; 8 July 1898 – 12 March 1980) was a Hungarian Communist leader in the period after World War II and briefly in 1956 the most powerful man in Hungary as the second secretary of its ruling communist party.

Ear ...

's ambition to make Hungary a land made out of "steel and iron" led to a decline in the national standards of living

Standard of living is the level of income, comforts and services available, generally applied to a society or location, rather than to an individual. Standard of living is relevant because it is considered to contribute to an individual's qualit ...

. At this point Rákosi had started distrusting Kádár, leading Kádár to resign as Ministry of the Interior

An interior ministry (sometimes called a ministry of internal affairs or ministry of home affairs) is a government department that is responsible for internal affairs.

Lists of current ministries of internal affairs

Named "ministry"

* Ministr ...

citing health and stress reasons for his choice. Kádár believed the longer down the ladder he climbed there was a bigger chance of not being purged. In this he was wrong, and he along with new Minister of the Interior Sándor Zöld

Sándor Zöld (19 May 1913 – 20 April 1951) was a Hungarian communist politician, who served as interior minister between 1950 and 1951. He followed János Kádár in this position.

Born in Nagyvárad (today Oradea, Romania), his famil ...

, were criticised for not doing a proper enough job to remove the anti-socialist movement within the country. Kádár would later refute most of the allegations the Rákosi leadership put against, but to no avail, and for every letter he wrote to refute an allegation another allegation was put against him. He eventually gave up and in one letter Kádár even admitted to his faults; claiming that he was still "politically backward" and "ideologically untrained" when he headed the prewar Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

as First Secretary. Kádár concluded that he had been fooled by the capitalists and therefore offered his resignation

Resignation is the formal act of leaving or quitting one's office or position. A resignation can occur when a person holding a position gained by election or appointment steps down, but leaving a position upon the expiration of a term, or choos ...

from active politics. Instead of resigning, and losing his seats in the Central Committee and the Politburo, his memberships in these organisations were renewed at the party congress. Believing that his position was secure and that Rákosi had given him another chance, Kádár thought nothing more of it. This proved to be wrong, and by the end of March 1951, Rákosi informed the Soviets that Kádár along with Zöld and Gyula Kállai

Gyula Kállai (; 1 June 1910 – 12 March 1996) was a Hungarian Communist politician who served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the People's Republic of Hungary from 1965 to 1967 and as Speaker of the National Assembly of Hungary 19 ...

were to be imprisoned.

On 18 April 1951, Zöld had killed his whole family and committed suicide after finding out that Rákosi and his associates had decided to purge him from the party. When the authorities found their bodies, they decided to quickly gather the remaining two before they did something rash too. Kádár, who did not know what had just taken place, was at home taking care of his wife Maria, who had been in and out of the hospital. The Hungarian leadership decided to call him, asking Kádár to meet them at the party headquarters, when leaving his home he was stopped by ÁVH officers and the ÁVH head Gábor Péter.

Only a year later, Kádár found himself the defendant in a show trial of his own—on false charges of having been a spy of Horthy's police. This time it was Kádár who was beaten by the security police and urged to "confess". During Kádár's interrogation, the ÁVH reportedly beat him, smeared him with mercury to prevent his skin pores from breathing, and had his questioner urinate into his pried-open mouth. However, at the 1954 rehearing of his trial, when asked if he had been maltreated, he answered "Physically no", a denial he repeated in later interviews towards the end of his life. It is thought by some that the stories of brutality were intended to portray him as a victim of Stalinist torture in order to counter his image at home and abroad as a Soviet stooge.

Kádár was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. His incarceration included three years of solitary confinement, conditions far worse than he suffered while imprisoned under the Horthy regime. He was released from prison in July 1954, after the death of Stalin and the appointment of Imre Nagy

Imre Nagy (; 7 June 1896 – 16 June 1958) was a Hungarian communist politician who served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers (''de facto'' Prime Minister) of the Hungarian People's Republic from 1953 to 1955. In 1956 Nagy became leader ...

as Prime Minister in 1953.

Kádár accepted the offer to act as party secretary in the heavily industrialized 13th district of Budapest. He rose to prominence quickly, building up a large following among workers who demanded increased freedom for trade unions.

Role in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956

Rákosi was forced to resign in 1956, replaced by Gerő. On 23 October 1956, students marched through Budapest intending to present a petition to the government. The procession swelled as several people poured onto the streets. Gerő replied with a harsh speech that angered the people, and police opened fire. It proved to be the start of the

Rákosi was forced to resign in 1956, replaced by Gerő. On 23 October 1956, students marched through Budapest intending to present a petition to the government. The procession swelled as several people poured onto the streets. Gerő replied with a harsh speech that angered the people, and police opened fire. It proved to be the start of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 10 November 1956; hu, 1956-os forradalom), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was a countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the Hung ...

. As the revolution spread throughout the country, Nagy was called back as Prime Minister.

The Hungarian Working People's Party decided to dissolve itself and to reorganize itself as the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party

The Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party ( hu, Magyar Szocialista Munkáspárt, MSZMP) was the ruling Marxist–Leninist party of the Hungarian People's Republic between 1956 and 1989. It was organised from elements of the Hungarian Working P ...

. On 25 October 1956, Kádár was elected General Secretary. He was also a member of the Nagy Government as Minister of State.

Nagy began a process of liberalization, removing state controls over the press, releasing many political prisoners, and expressing wishes to withdraw Hungary from the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

. He formed a coalition government. Although the Soviet leaders issued a statement that they strove to establish a new relationship with Hungary on the basis of mutual respect and equality, in the first days of November, the Presidium of the Soviet Communist Party took a decision to crush the revolution by force.

On 1 November 1956, Kádár, together with Ferenc Münnich

Ferenc Münnich (; 18 November 1886 – 29 November 1967) was a Hungarian Communist politician who served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the People's Republic of Hungary from 1958 to 1961.

He served in the Austro-Hungarian Army ...

, left Hungary for Moscow with the support of the Soviet Embassy in Budapest. There the Soviet leaders tried to convince him that a "counter-revolution" was unfolding in Hungary that must be put to an end at any cost. He only agreed to change sides when the Soviet leaders informed him that the decision had already been taken to crush the revolution with the help of the Soviet troops stationed in Hungary. He was also told that unless he agreed to become prime minister in the new government, the Rákosi–Gerő leadership would be reinstalled. Although he was under duress, he did not, by his own admission, resist as much as he could have. In a speech given on 12 April 1989, he confessed to having played a role in Nagy's execution, calling it his "own personal tragedy." Writing in 1961, American journalist John Gunther

John Gunther (August 30, 1901 – May 29, 1970) was an American journalist and writer.

His success came primarily by a series of popular sociopolitical works, known as the "Inside" books (1936–1972), including the best-selling '' Ins ...

said that "Kádár today looks like a man pursued by shadows, a walking corpse."

The Soviet tank divisions moved into Budapest with the purpose of crushing the revolution at dawn on 4 November 1956. The proclamation of the so-called Revolutionary Workers'-Peasants' Government of Hungary {{more citations needed, date=February 2015

The Revolutionary Workers'-Peasants' Government of Hungary (Hungarian: magyar Forradalmi Munkás-Paraszt Kormány or első Kádár-kormány) was formed during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 with Soviet s ...

, headed by Kádár, was broadcast from Szolnok

Szolnok (; also known by other alternative names) is the county seat of Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok county in central Hungary. A city with county rights, it is located on the banks of the Tisza river, in the heart of the Great Hungarian Plain, wh ...

the same day.

He announced a "Fifteen Point Programme" for this new government:

# To secure Hungary's national independence and sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

# To protect the people's democratic

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

and socialist system from all attacks

# To end fratricidal fighting and to restore order

# To establish close fraternal relations with other socialist countries on the basis of complete equality and non-interference

# To cooperate peacefully with all nations irrespective of form of government

# To quickly and substantially raise the standard of living

Standard of living is the level of income, comforts and services available, generally applied to a society or location, rather than to an individual. Standard of living is relevant because it is considered to contribute to an individual's quality ...

for all in Hungary

# Modification of the Five Year Plan, to allow for this increase in the standard of living

# Elimination of bureaucracy and the broadening of democracy, in the workers' interest

# On the basis of the broadened democracy, management by the workers must be implemented in factories

A factory, manufacturing plant or a production plant is an industrial facility, often a complex consisting of several buildings filled with machinery

A machine is a physical system using power to apply forces and control movement to p ...

and enterprise

Enterprise (or the archaic spelling Enterprize) may refer to:

Business and economics

Brands and enterprises

* Enterprise GP Holdings, an energy holding company

* Enterprise plc, a UK civil engineering and maintenance company

* Enterprise ...

s

# To develop agricultural production, abolish compulsory deliveries and grant assistance to individual farmers

# To guarantee democratic elections in the already existing administrative bodies and Revolutionary Councils

# Support for artisan

An artisan (from french: artisan, it, artigiano) is a skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects partly or entirely by hand. These objects may be functional or strictly decorative, for example furniture, decorative art, ...

s and retail trade

# Development of Hungarian culture

Hungarian culture is characterised by its distinctive cuisine, folk traditions, poetry, theatre, religious customs, music and traditional embroidered garments. Hungarian folk traditions range from embroidery, decorated pottery and carvings ...

in the spirit of Hungary's progressive traditions

# The Hungarian Revolutionary Worker-Peasant Government, acting in the interest of our people, requested the Red Army to help our nation smash the sinister forces of reaction

Reaction may refer to a process or to a response to an action, event, or exposure:

Physics and chemistry

*Chemical reaction

*Nuclear reaction

*Reaction (physics), as defined by Newton's third law

* Chain reaction (disambiguation).

Biology and me ...

and restore order and calm in Hungary

# To negotiate with the forces of the Warsaw Pact on the withdrawal of troops from Hungary following the end of the crisis

The 15th point was withdrawn after pressure from the USSR that a 200,000 strong Soviet detachment be garrisoned in Hungary. This development allowed Kádár to divert huge defense funds to welfare.

Nagy, along with Georg Lukács

Georg may refer to:

* ''Georg'' (film), 1997

*Georg (musical), Estonian musical

* Georg (given name)

* Georg (surname)

* , a Kriegsmarine coastal tanker

See also

* George (disambiguation)

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* ...

, Géza Losonczy

Géza Losonczy (5 May 1917, Érsekcsanád – 21 December 1957) was a Hungarian journalist and politician. He was associated with the reformist faction of the Hungarian communist party.

During the 1956 Hungarian revolution, he joined the Imr ...

and László Rajk's widow, Júlia, fled to the Yugoslav Embassy. Kádár promised them safe return home at their request but failed to keep this promise as the Soviet party leaders decided that Imre Nagy

Imre Nagy (; 7 June 1896 – 16 June 1958) was a Hungarian communist politician who served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers (''de facto'' Prime Minister) of the Hungarian People's Republic from 1953 to 1955. In 1956 Nagy became leader ...

and the other members of the government who had sought asylum at the Yugoslav Embassy should be deported to Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

. Later on, a trial was instituted to establish the responsibility of the Imre Nagy Government in the 1956 events. Although it was adjourned several times, the defendants were eventually convicted of treason and conspiracy to overthrow the "democratic state order". Imre Nagy

Imre Nagy (; 7 June 1896 – 16 June 1958) was a Hungarian communist politician who served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers (''de facto'' Prime Minister) of the Hungarian People's Republic from 1953 to 1955. In 1956 Nagy became leader ...

, Pál Maléter

Pál Maléter (4 September 1917 – 16 June 1958) was the military leader of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution.

Maléter was born to Hungarian parents in Eperjes, a city in Sáros County, in the northern part of Historical Hungary, today Prešo ...

and Miklós Gimes

Miklós Gimes (23 December 1917 in Budapest – 16 June 1958) was a Hungarian journalist and politician, notable for his role in the 1956 Hungarian revolution. He was executed along with Imre Nagy and Pál Maléter in 1958 for treason.

His p ...

were sentenced to death and executed on 16 June 1958. Géza Losonczy and both died in prison under suspicious circumstances during the court proceedings.

Kádár era

Kádár assumed power in a critical situation. The country was under Soviet military administration for several months. The fallen leaders of the Communist Party took refuge in the Soviet Union and were planning to regain power in Hungary. The Chinese, East German, and Czechoslovak leaders demanded severe reprisals against the perpetrators of the "counter-revolution". Despite the distrust surrounding the new leadership and the economic difficulties, Kádár was able to normalize the situation in a remarkably short time. This was due to the realization that, under the circumstances, it was impossible to break away from the Communist bloc. The Hungarian people realized that the promises of the West to help the Hungarian revolution were unfounded and that the logic of the Cold War determined the outcome. Hungary remained part of the Soviet sphere of influence with the tacit agreement of the West. Though influenced strongly by the Soviet Union, Kádár enacted a policy slightly contrary to that of Moscow, for example, allowing considerably large private plots for farmers of

Kádár assumed power in a critical situation. The country was under Soviet military administration for several months. The fallen leaders of the Communist Party took refuge in the Soviet Union and were planning to regain power in Hungary. The Chinese, East German, and Czechoslovak leaders demanded severe reprisals against the perpetrators of the "counter-revolution". Despite the distrust surrounding the new leadership and the economic difficulties, Kádár was able to normalize the situation in a remarkably short time. This was due to the realization that, under the circumstances, it was impossible to break away from the Communist bloc. The Hungarian people realized that the promises of the West to help the Hungarian revolution were unfounded and that the logic of the Cold War determined the outcome. Hungary remained part of the Soviet sphere of influence with the tacit agreement of the West. Though influenced strongly by the Soviet Union, Kádár enacted a policy slightly contrary to that of Moscow, for example, allowing considerably large private plots for farmers of collective farm

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

s.

Starting in the early 1960s, he gradually lifted Rákosi's more draconian measures against free speech and movement, and also eased some restrictions on cultural activities. He even tolerated

Starting in the early 1960s, he gradually lifted Rákosi's more draconian measures against free speech and movement, and also eased some restrictions on cultural activities. He even tolerated samizdat

Samizdat (russian: самиздат, lit=self-publishing, links=no) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the document ...

publications to a far greater extent than his counterparts. As Kádár once said, "what kind of regime is it that doesn't have even a tiny little opposition, just for show? But there's also the fact that they can't go beyond a certain limit, and if they try, they'll pay for it." Hungarians had much more freedom than their Eastern Bloc counterparts to go about their daily lives.

The result was a regime that was far more humane than other Communist regimes, especially so when compared to the first seven years of undisguised Communist rule in Hungary. However, it was not a liberal regime in any sense. The Communists maintained absolute control over the government and also encouraged citizens to join party organizations. The National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the rep ...

, like its counterparts in other Communist countries, did little more than approve decisions already made by the MSZMP and its Politburo. Voters were presented with a single list from the Patriotic People's Front

The Patriotic People's Front ( hu, Hazafias Népfront, HNF) was originally a Hungarian political resistance movement during World War II which become later an alliance of political parties in the Hungarian People's Republic. In the latter role, ...

, which was dominated by the MSZMP. All prospective candidates had to accept the Front's program in order to stand; indeed, Kádár and his advisers used the Front to weed out candidates they deemed unacceptable. The secret police, the Ministry of Internal Affairs III

Department III of the Ministry of Internal Affairs ( hu, Belügyminisztérium III. Főcsoportfőnökség), also known as the State Security Department of the Ministry of Interior ( hu, Belügyminisztérium Állambiztonsági Szervek), was the se ...

, while operating with somewhat more restraint than their counterparts in other Eastern Bloc countries (such as the AVH), was nonetheless a feared tool of government control. The Hungarian media remained under censorship that was considered fairly onerous by Western standards, but far less stringent than was the case in other Communist countries.

As a result of the relatively high standard of living, and more relaxed restrictions on speech, movement, and culture than that of other Eastern Bloc countries, Hungary was generally considered one of the better countries in which to live in Eastern Europe during the Cold War. The dramatic fall in living standards after the fall of Communism led to some nostalgia about the Kádár era. However, the relatively high living standards had their price in the form of 58% of GDP or US$22 bn state debt left behind by the Kádár régime. As mentioned above, the regime's cultural and social policies were still somewhat authoritarian; their impact on contemporary Hungarian culture is still a matter of considerable debate.

While Kádár's regime remained strictly loyal to the Soviet Union in foreign policy, its intent was to establish a national consensus around its domestic policies. In notable contrast to Rákosi, who repeatedly declared "he who is not with us is against us" in his rally speeches, Kádár declared that "who is not against us is with us." Kádár was the first Eastern European leader to develop closer ties with the Social Democratic parties of Western Europe. He also attempted to establish good relations with the United States, though could only go so far due to the limitations imposed by Kádár's ultimate commitment to communist internationalism. He tried to mediate between the leaders of the Czechoslovak reform movement of 1968 and the Soviet leadership to avert the danger of military intervention. When, however, the decision was taken by the Soviet leaders to intervene in order to suppress the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Se ...

, Kádár decided to participate in the Warsaw Pact operation.

During Kádár's rule, international tourism

International tourism is tourism that crosses national borders. Globalisation has made tourism a popular global leisure activity. The World Tourism Organization defines tourists as people "traveling to and staying in places outside their usual e ...

increased dramatically, with many tourists (including Hungarians who emigrated 1956 or before) from Canada, the US, and Western Europe bringing much-needed money into Hungary. Hungary built strong relations with developing countries and many foreign students arrived. The "Holy Crown

The Holy Crown of Hungary ( hu, Szent Korona; sh, Kruna svetoga Stjepana; la, Sacra Corona; sk, Svätoštefanská koruna , la, Sacra Corona), also known as the Crown of Saint Stephen, named in honour of Saint Stephen I of Hungary, was the ...

" (referred to in the media as the "Hungarian Crown", so as to prevent it carrying a political symbolism of the Horthy régime or an allusion to Christianity) and regalia of Hungarian kings was returned to Budapest by the United States in 1978.

Kádár was known for his simple and modest lifestyle and avoided the self-indulgence persona of other Communist leaders. Although he was never personally corrupt, he sometimes overlooked corrupt dealings of other members of the elite to an extent. To strengthen his popularity, whispering propaganda depicted him as totally intolerant to corruption by his underlings. Playing chess was one of his favorite pastimes. However, he was an avid hunter (hunting for sport used to be an aristocratic hobby before 1945 in Hungary and this pattern continued during the Communist era when it became a cherished pastime and occasion for the new elite to informally socialize and to get drunk), and was a member of an exclusive hunting association made up by Party leaders and other dignitaries. He wasn't a heavy drinker though and demanded modesty when he was present. Also, foreign guests often visited the Hungarian forests too, from the Shah of Iran

This is a list of monarchs of Persia (or monarchs of the Iranic peoples, in present-day Iran), which are known by the royal title Shah or Shahanshah. This list starts from the establishment of the Medes around 671 BCE until the deposition of the ...

through Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 2 ...

to the King of Nepal, and Leonid Brezhnev hunted with Kádár several times. The popularity of this "gentleman's sport" among Communist leaders was marked by political decisions made on hunting excursions.

Kádár was awarded the

Kádár was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize

The International Lenin Peace Prize (russian: международная Ленинская премия мира, ''mezhdunarodnaya Leninskaya premiya mira)'' was a Soviet Union award named in honor of Vladimir Lenin. It was awarded by a pane ...

(1975–76). He was also awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union

The title Hero of the Soviet Union (russian: Герой Советского Союза, translit=Geroy Sovietskogo Soyuza) was the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, awarded together with the Order of Lenin personally or collectively for ...

on 3 April 1964.

Resignation, final months and death

János Kádár held power in Hungary until the "apparat coup" in the spring of 1988, when he resigned under pressure as General Secretary in the face of mounting economic difficulties and his own ill health. At a party conference in Budapest on 22 May 1988, at which half a dozen of his Politburo associates were also removed, Kádár announced his resignation and was officially replaced as General Secretary by Prime MinisterKároly Grósz

Károly Grósz (1 August 1930 – 7 January 1996) was a Hungarian communist politician, who served as the General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party from 1988 to 1989.

Early career

Grósz was born in Miskolc, Hungary. He joi ...