Justice Thurgood Marshall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an

Marshall next turned to the issue of segregation in primary and secondary schools. The NAACP brought suit to challenge segregated schools in Delaware, the District of Columbia, Kansas, South Carolina, and Virginia, arguing both that there were disparities between the physical facilities provided for blacks and whites and that segregation was inherently harmful to African-American children. Marshall helped to try the South Carolina case. He called numerous social scientists and other expert witnesses to testify regarding the harms of segregation; these included the psychology professor Ken Clark, who testified that segregation in schools caused

Marshall next turned to the issue of segregation in primary and secondary schools. The NAACP brought suit to challenge segregated schools in Delaware, the District of Columbia, Kansas, South Carolina, and Virginia, arguing both that there were disparities between the physical facilities provided for blacks and whites and that segregation was inherently harmful to African-American children. Marshall helped to try the South Carolina case. He called numerous social scientists and other expert witnesses to testify regarding the harms of segregation; these included the psychology professor Ken Clark, who testified that segregation in schools caused

Marshall remained on the Supreme Court for nearly twenty-four years, serving until his retirement in 1991. The Court to which he was appointed—the

Marshall remained on the Supreme Court for nearly twenty-four years, serving until his retirement in 1991. The Court to which he was appointed—the

As the Court became increasingly conservative, Marshall found himself dissenting in numerous cases regarding racial discrimination. When the majority held in ''

As the Court became increasingly conservative, Marshall found himself dissenting in numerous cases regarding racial discrimination. When the majority held in ''

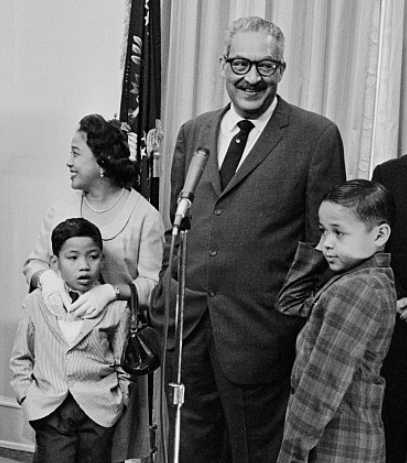

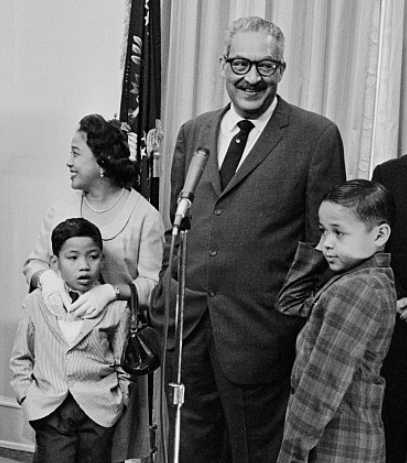

Marshall wed Vivian "Buster" Burey on September 4, 1929, while he was a student at Lincoln University. They remained married until her death from cancer in 1955. Marshall married Cecilia "Cissy" Suyat, an NAACP secretary, eleven months later; they had two children: Thurgood Jr. and

Marshall wed Vivian "Buster" Burey on September 4, 1929, while he was a student at Lincoln University. They remained married until her death from cancer in 1955. Marshall married Cecilia "Cissy" Suyat, an NAACP secretary, eleven months later; they had two children: Thurgood Jr. and

Marshall did not wish to retire—he frequently said "I was appointed to a life term, and I intend to serve it"—but he had been in ill health for many years, and Brennan's retirement in 1990 left him unhappy and isolated on the Court. The 82-year-old justice announced on June 27, 1991, that he would retire. When asked at a

Marshall did not wish to retire—he frequently said "I was appointed to a life term, and I intend to serve it"—but he had been in ill health for many years, and Brennan's retirement in 1990 left him unhappy and isolated on the Court. The 82-year-old justice announced on June 27, 1991, that he would retire. When asked at a

According to the scholar Daniel Moak, Marshall "profoundly shaped the political direction of the United States", "transformed constitutional law", and "opened up new facets of citizenship to black Americans". For Tushnet, he was "probably the most important American lawyer of the twentieth century"; in the view of the political scientist

According to the scholar Daniel Moak, Marshall "profoundly shaped the political direction of the United States", "transformed constitutional law", and "opened up new facets of citizenship to black Americans". For Tushnet, he was "probably the most important American lawyer of the twentieth century"; in the view of the political scientist

Justice Thurgood Marshall: A Selected Bibliography

', ( Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Washington, DC, February 1993). * * * Mack, Kenneth W., (2012).

Representing the Race: The Creation of the Civil Rights Lawyer

'. Harvard University Press. . * Marshall, Thurgood (1950). "Mr. Justice

Oral History Interview with Thurgood Marshall

from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library

FBI file on Thurgood Marshall

{{DEFAULTSORT:Marshall, Thurgood 1908 births 1993 deaths 20th-century African-American people 20th-century American judges Activists for African-American civil rights African-American Episcopalians African-American judges African-American lawyers American civil rights lawyers Articles containing video clips Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Howard University School of Law alumni Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States Lawyers from Baltimore Lincoln University (Pennsylvania) alumni Maryland Democrats NAACP activists People from Southwest (Washington, D.C.) Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Spingarn Medal winners United States court of appeals judges appointed by John F. Kennedy United States federal judges appointed by Lyndon B. Johnson United States Solicitors General

associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is any member of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the Judiciary Act of 18 ...

from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme Court's first African-American justice. Prior to his judicial service, he was an attorney who fought for civil rights, leading the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (NAACP LDF, the Legal Defense Fund, or LDF) is a leading United States civil rights organization and law firm based in New York City.

LDF is wholly independent and separate from the NAACP. Altho ...

. Marshall coordinated the assault on racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

in schools. He won 29 of the 32 civil rights cases he argued before the Supreme Court, culminating in the Court's landmark 1954 decision in '' Brown v. Board of Education'', which rejected the separate but equal doctrine and held segregation in public education to be unconstitutional. President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

appointed Marshall to the Supreme Court in 1967. A staunch liberal, he frequently dissented as the Court became increasingly conservative.

Born in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Maryland, Marshall attended Lincoln University and the Howard University School of Law

Howard University School of Law (Howard Law or HUSL) is the law school of Howard University, a private, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is one of the oldest law schools in the country and the oldes ...

. At Howard, he was mentored by Charles Hamilton Houston, who taught his students to be "social engineers" willing to use the law to fight for civil rights. Marshall opened a law practice in Baltimore but soon joined Houston at the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

in New York. They worked together on the segregation case of ''Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada

''Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada'', 305 U.S. 337 (1938), was a United States Supreme Court decision holding that states which provided a school to white students had to provide in-state education to blacks as well. States could satisfy this ...

''; after Houston returned to Washington, Marshall took his place as special counsel of the NAACP, and he became director-counsel of the newly formed NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. He participated in numerous landmark Supreme Court cases involving civil rights, including ''Smith v. Allwright

''Smith v. Allwright'', 321 U.S. 649 (1944), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court with regard to voting rights and, by extension, racial desegregation. It overturned the Texas state law that authorized parties to set their in ...

'', ''Morgan v. Virginia

''Morgan v. Virginia'', 328 U.S. 373 (1946), is a major United States Supreme Court case. In this landmark 1946 ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 7–1 that Virginia's state law enforcing segregation on interstate buses was unconstitutional.

...

'', ''Shelley v. Kraemer

''Shelley v. Kraemer'', 334 U.S. 1 (1948), is a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark United States Supreme Court case that held that racially restrictive housing Covenant (law), covenants cannot legally be enforced.

The ...

'', ''McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents __NOTOC__

''McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents'', 339 U.S. 637 (1950), was a Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court case that prohibited racial segregation in state supported graduate or professional education.. The unani ...

'', ''Sweatt v. Painter

''Sweatt v. Painter'', 339 U.S. 629 (1950), was a U.S. Supreme Court case that successfully challenged the "separate but equal" doctrine of racial segregation established by the 1896 case ''Plessy v. Ferguson''. The case was influential in the lan ...

'', ''Brown'', and ''Cooper v. Aaron

''Cooper v. Aaron'', 358 U.S. 1 (1958), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, which denied the school board of Little Rock, Arkansas, the right to delay racial desegregation for 30 months. On September 12, 1958, th ...

''. His approach to desegregation cases emphasized the use of sociological data to show that segregation was inherently unequal.

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

appointed Marshall to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (in case citations, 2d Cir.) is one of the thirteen United States Courts of Appeals. Its territory comprises the states of Connecticut, New York (state), New York and Vermont. The court h ...

, where he favored a broad interpretation of constitutional protections. Four years later, Johnson appointed him as the U.S. Solicitor General

The solicitor general of the United States is the fourth-highest-ranking official in the United States Department of Justice. Elizabeth Prelogar has been serving in the role since October 28, 2021.

The United States solicitor general represent ...

. In 1967, Johnson nominated Marshall to replace Justice Tom C. Clark

Thomas Campbell Clark (September 23, 1899June 13, 1977) was an American lawyer who served as the 59th United States Attorney General from 1945 to 1949 and as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1949 to 1967.

Clark ...

on the Supreme Court; despite opposition from Southern senators, he was confirmed by a vote of 69 to 11. He was often in the majority during the consistently liberal Warren Court

The Warren Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of the United States during which Earl Warren served as Chief Justice. Warren replaced the deceased Fred M. Vinson as Chief Justice in 1953, and Warren remained in office until ...

period, but after appointments by President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

made the Court more conservative, Marshall frequently found himself in dissent. His closest ally on the Court was Justice William J. Brennan Jr.

William Joseph "Bill" Brennan Jr. (April 25, 1906 – July 24, 1997) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1956 to 1990. He was the seventh-longest serving justice ...

, and the two voted the same way in most cases.

Marshall's jurisprudence was pragmatic and drew on his real-world experience. His most influential contribution to constitutional doctrine, the "sliding-scale" approach to the Equal Protection Clause

The Equal Protection Clause is part of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause, which took effect in 1868, provides "''nor shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal ...

, called on courts to apply a flexible balancing test

A balancing test is any judicial test in which the jurists weigh the importance of multiple factors in a legal case. Proponents of such legal tests argue that they allow a deeper consideration of complex issues than a bright-line rule can allow. B ...

instead of a more rigid tier-based analysis. He fervently opposed the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

, which in his view constituted cruel and unusual punishment

Cruel and unusual punishment is a phrase in common law describing punishment that is considered unacceptable due to the suffering, pain, or humiliation it inflicts on the person subjected to the sanction. The precise definition varies by jurisd ...

; he and Brennan dissented in more than 1,400 cases in which the majority refused to review a death sentence. He favored a robust interpretation of the First Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

in decisions such as ''Stanley v. Georgia

''Stanley v. Georgia'', 394 U.S. 557 (1969), was a U.S. Supreme Court decision that helped to establish an implied "right to privacy" in U.S. law in the form of mere possession of obscene materials.

The Georgia home of Robert Eli Stanley, a susp ...

'', and he supported abortion rights in ''Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States conferred the right to have an abortion. The decision struck down many federal and st ...

'' and other cases. Marshall retired from the Supreme Court in 1991 and was replaced by Clarence Thomas

Clarence Thomas (born June 23, 1948) is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President George H. W. Bush to succeed Thurgood Marshall and has served since 199 ...

. He died in 1993.

Early life and education

Thurgood Marshall was born on July 2, 1908, inBaltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Maryland, to Norma and William Canfield Marshall. His father held various jobs as a waiter in hotels, in clubs, and on railroad cars, and his mother was a schoolteacher. The family moved to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

in search of better employment opportunities not long after Thurgood's birth; they returned to Baltimore when he was six years old. He was an energetic and boisterous child who frequently found himself in trouble. Following legal cases was one of William's hobbies, and Thurgood oftentimes went to court with him to observe the proceedings. Marshall later said that his father "never told me to become a lawyer, but he turned me into one... He taught me how to argue, challenged my logic on every point, by making me prove every statement I made, even if we were discussing the weather."

Marshall attended the Colored High and Training School (later Frederick Douglass High School) in Baltimore, graduating in 1925 with honors. He then enrolled at Lincoln University in Chester County, Pennsylvania, the oldest college for African Americans in the United States. The mischievous Marshall was suspended for two weeks in the wake of a hazing

Hazing (American English), initiation, beasting (British English), bastardisation (Australian English), ragging (South Asian English) or deposition refers to any activity expected of someone in joining or participating in a group that humiliates, ...

incident, but he earned good grades in his classes and led the school's debating team to numerous victories. His classmates included the poet Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1901 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary art form called jazz poetry, Hug ...

. Upon his graduation with honors in 1930 with a bachelor's degree in American literature and philosophy, Marshall—being unable to attend the all-white University of Maryland Law School

The University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law (formerly University of Maryland School of Law) is the law school of the University of Maryland, Baltimore and is located in Baltimore City, Maryland, U.S. Its location places Maryland ...

—applied to Howard University School of Law

Howard University School of Law (Howard Law or HUSL) is the law school of Howard University, a private, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is one of the oldest law schools in the country and the oldes ...

in Washington, D.C., and was admitted. At Howard, he was mentored by Charles Hamilton Houston, who taught his students to be "social engineers" willing to use the law to fight for civil rights. Marshall graduated first in his class in June 1933 and passed the Maryland bar examination

A bar examination is an examination administered by the bar association of a jurisdiction that a lawyer must pass in order to be admitted to the bar of that jurisdiction.

Australia

Administering bar exams is the responsibility of the bar associa ...

later that year.

Legal career

Marshall started a law practice in Baltimore, but it was not financially successful, partially because he spent much of his time working for the benefit of the community. He volunteered with the Baltimore branch of theNational Association for the Advancement of Colored Persons

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.& ...

(NAACP). In 1935, Marshall and Houston brought suit against the University of Maryland on behalf of Donald Gaines Murray, an African American whose application to the university's law school had been rejected on account of his race. In that case—''Murray v. Pearson

''Murray v. Pearson'' was a Maryland Court of Appeals decision which found "the state has undertaken the function of education in the law, but has omitted students of one race from the only adequate provision made for it, and omitted them solely be ...

''—Judge Eugene O'Dunne

Eugene O'Dunne or Eugene Antonio Dunne (June 22, 1875 – October 30, 1959) was a judge of the Supreme Bench of Baltimore City.

Personal life

Born in Tucson, O'Dunne was the son of Judge Edmund F. Dunne, who was Chief Justice of the Arizona Terr ...

ordered that Murray be admitted, and the Maryland Court of Appeals

The Supreme Court of Maryland is the state supreme court, highest court of the U.S. state of Maryland. Its name was changed on December 14, 2022, from the Maryland Court of Appeals, after a voter-approved change to the state constitution. The cou ...

affirmed, holding that it violated equal protection to admit white students to the law school while keeping blacks from being educated in-state. The decision was never appeal

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

ed to the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

and therefore did not apply nationwide, but it pleased Marshall, who later said that he had filed the lawsuit "to get even with the bastards" who had kept him from attending the school himself.

In 1936, Marshall joined Houston, who had been appointed as the NAACP's special counsel, in New York City, serving as his assistant. They worked together on the landmark case of ''Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada

''Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada'', 305 U.S. 337 (1938), was a United States Supreme Court decision holding that states which provided a school to white students had to provide in-state education to blacks as well. States could satisfy this ...

'' (1938)''.'' When Lloyd Lionel Gaines's application to the University of Missouri's law school was rejected on account of his race, he filed suit, arguing that his equal-protection rights had been violated because he had not been provided with a legal education substantially equivalent to that which white students received. After Missouri courts rejected Gaines's claims, Houston—joined by Marshall, who helped to prepare the brief—sought review in the U.S. Supreme Court. They did not challenge the Court's decision in ''Plessy v. Ferguson

''Plessy v. Ferguson'', 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality ...

'' (1896), which had accepted the "separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protecti ...

" doctrine; instead, they argued that Gaines had been denied an equal education. In an opinion by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, the justices agreed, holding that if Missouri gave whites the opportunity to attend law school in-state, it was required to do the same for blacks.

Houston returned to Washington in 1938, and Marshall assumed his position as special counsel the following year. He also became the director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Inc. (the Inc Fund), which had been established as a separate organization for tax purposes. In addition to litigating cases and arguing matters before the Supreme Court, he was responsible for raising money, managing the Inc Fund, and conducting public-relations work. Marshall litigated a number of cases involving unequal salaries for African Americans, winning nearly all of them; by 1945, he had ended salary disparities in major Southern cities and earned a reputation as a prominent figure in the civil rights movement. He also defended individuals who had been charged with crimes before both trial courts and the Supreme Court. Of the thirty-two civil rights cases that Marshall argued before the Supreme Court, he won twenty-nine. He and W. J. Durham wrote the brief in ''Smith v. Allwright

''Smith v. Allwright'', 321 U.S. 649 (1944), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court with regard to voting rights and, by extension, racial desegregation. It overturned the Texas state law that authorized parties to set their in ...

'' (1944), in which the Court ruled the white primary

White primaries were primary elections held in the Southern United States in which only white voters were permitted to participate. Statewide white primaries were established by the state Democratic Party units or by state legislatures in South C ...

unconstitutional, and he successfully argued both ''Morgan v. Virginia

''Morgan v. Virginia'', 328 U.S. 373 (1946), is a major United States Supreme Court case. In this landmark 1946 ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 7–1 that Virginia's state law enforcing segregation on interstate buses was unconstitutional.

...

'' (1946), involving segregation on interstate buses, and a companion case

The term companion cases refers to a group of two or more cases which are consolidated by an appellate court while on appeal and are decided together because they concern one or more common legal issues. Depending on the facts of each case, the ...

to ''Shelley v. Kraemer

''Shelley v. Kraemer'', 334 U.S. 1 (1948), is a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark United States Supreme Court case that held that racially restrictive housing Covenant (law), covenants cannot legally be enforced.

The ...

'' (1948), involving racially restrictive covenants.

In the years after 1945, Marshall resumed his offensive against racial segregation in schools. Together with his Inc Fund colleagues, he devised a strategy that emphasized the inherent educational disparities caused by segregation rather than the physical differences between the schools provided for blacks and whites. The Court ruled in Marshall's favor in ''Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma

''Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma'', 332 U.S. 631 (1948), is a ''per curiam'' United States Supreme Court decision involving racial segregation toward African Americans by the University of Oklahoma and the application of ...

'' (1948), ordering that Oklahoma provide Ada Lois Sipuel with a legal education, although the justices declined to order that she be admitted to the state's law school for whites. In 1950, Marshall brought two cases involving education to the Court: ''McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents __NOTOC__

''McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents'', 339 U.S. 637 (1950), was a Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court case that prohibited racial segregation in state supported graduate or professional education.. The unani ...

'', which was George W. McLaurin's challenge to unequal treatment at the University of Oklahoma

The University of Oklahoma (OU) is a Public university, public research university in Norman, Oklahoma. Founded in 1890, it had existed in Oklahoma Territory near Indian Territory for 17 years before the two Territories became the state of Oklahom ...

's graduate school, and ''Sweatt v. Painter

''Sweatt v. Painter'', 339 U.S. 629 (1950), was a U.S. Supreme Court case that successfully challenged the "separate but equal" doctrine of racial segregation established by the 1896 case ''Plessy v. Ferguson''. The case was influential in the lan ...

'', which was Heman Sweatt

Heman Marion Sweatt (December 11, 1912 – October 3, 1982) was an African-American civil rights activist who confronted Jim Crow laws. He is best known for the '' Sweatt v. Painter'' lawsuit, which challenged the "separate but equal" doctrine and ...

's challenge to his being required to attend a blacks-only law school in Texas. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of both McLaurin and Sweatt on the same day; although the justices did not overrule ''Plessy'' and the separate but equal doctrine, they rejected discrimination against African-American students and the provisions of schools for blacks that were inferior to those provided for whites.

Marshall next turned to the issue of segregation in primary and secondary schools. The NAACP brought suit to challenge segregated schools in Delaware, the District of Columbia, Kansas, South Carolina, and Virginia, arguing both that there were disparities between the physical facilities provided for blacks and whites and that segregation was inherently harmful to African-American children. Marshall helped to try the South Carolina case. He called numerous social scientists and other expert witnesses to testify regarding the harms of segregation; these included the psychology professor Ken Clark, who testified that segregation in schools caused

Marshall next turned to the issue of segregation in primary and secondary schools. The NAACP brought suit to challenge segregated schools in Delaware, the District of Columbia, Kansas, South Carolina, and Virginia, arguing both that there were disparities between the physical facilities provided for blacks and whites and that segregation was inherently harmful to African-American children. Marshall helped to try the South Carolina case. He called numerous social scientists and other expert witnesses to testify regarding the harms of segregation; these included the psychology professor Ken Clark, who testified that segregation in schools caused self-hatred

Self-hatred is personal self-loathing or hatred of oneself, or low self-esteem which may lead to self-harm.

In psychology and psychiatry

The term "self-hatred" is used infrequently by psychologists and psychiatrists, who would usually describe ...

among African-American students and inflicted damage that was "likely to endure as long as the conditions of segregation exist". The five cases eventually reached the Supreme Court and were argued in December 1952. In contrast to the oratorical rhetoric of his adversary—John W. Davis

John William Davis (April 13, 1873 – March 24, 1955) was an American politician, diplomat and lawyer. He served under President Woodrow Wilson as the Solicitor General of the United States and the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom ...

, a former solicitor general and presidential candidate—Marshall spoke plainly and conversationally. He stated that the only possible justification for segregation "is an inherent determination that the people who were formerly in slavery, regardless of anything else, shall be kept as near that stage as possible. And now is the time, we submit, that this Court should make clear that that is not what our Constitution stands for." On May 17, 1954, after internal disagreements and a 1953 reargument, the Supreme Court handed down its unanimous decision in '' Brown v. Board of Education'', holding in an opinion by Chief Justice Earl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney, politician, and jurist who served as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presided over a major shift in American constitution ...

that: "in the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." When Marshall heard Warren read those words, he later said, "I was so happy I was numb".

The Court in ''Brown'' ordered additional arguments on the proper remedy for the constitutional violation that it had identified; in ''Brown'' II, decided in 1955, the justices ordered that desegregation proceed "with all deliberate speed". Their refusal to set a concrete deadline came as a disappointment to Marshall, who had argued for total integration to be completed by September 1956. In the years following the Court's decision, Marshall coordinated challenges to Virginia's "massive resistance

Massive resistance was a strategy declared by U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr. of Virginia and his brother-in-law James M. Thomson, who represented Alexandria in the Virginia General Assembly, to get the state's white politicians to pass laws and p ...

" to ''Brown'', and he returned to the Court to successfully argue ''Cooper v. Aaron

''Cooper v. Aaron'', 358 U.S. 1 (1958), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, which denied the school board of Little Rock, Arkansas, the right to delay racial desegregation for 30 months. On September 12, 1958, th ...

'' (1958), involving Little Rock

( The "Little Rock")

, government_type = Council-manager

, leader_title = Mayor

, leader_name = Frank Scott Jr.

, leader_party = D

, leader_title2 = Council

, leader_name2 ...

's attempt to delay integration. Marshall, who according to the legal scholar Mark Tushnet

Mark Victor Tushnet (born 18 November 1945) is an American legal scholar. He specializes in constitutional law and theory, including comparative constitutional law, and is currently the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Law at Harvard Law Sch ...

"gradually became a civil rights leader more than a civil rights lawyer", spent substantial amounts of time giving speeches and fundraising; in 1960, he accepted an invitation from Tom Mboya

Thomas Joseph Odhiambo Mboya (15August 19305July 1969) was a Kenyan trade unionist, educator, Pan-Africanist, author, independence activist, and statesman. He was one of the founding fathers of the Republic of Kenya.Kenya Human Rights Commissio ...

to help draft Kenya's constitution. By that year, Tushnet writes, he had become "the country's most prominent Supreme Court advocate".

Court of Appeals

PresidentJohn F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

, who according to Tushnet "wanted to demonstrate his commitment to the interests of African Americans without incurring enormous political costs", nominated Marshall to be a judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (in case citations, 2d Cir.) is one of the thirteen United States Courts of Appeals. Its territory comprises the states of Connecticut, New York and Vermont. The court has appellate juri ...

on September 23, 1961. The Second Circuit, which spanned New York, Vermont, and Connecticut, was at the time the nation's prominent appellate court. When Congress adjourned, Kennedy gave Marshall a recess appointment

In the United States, a recess appointment is an appointment by the president of a federal official when the U.S. Senate is in recess. Under the U.S. Constitution's Appointments Clause, the President is empowered to nominate, and with the advi ...

, and he took the oath of office on October 23.

Even after his recess appointment, Southern senators continued to delay Marshall's full confirmation for more than eight months. A subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations, a ...

postponed his hearing several times, leading Senator Kenneth Keating

Kenneth Barnard Keating (May 18, 1900 – May 5, 1975) was an American politician, diplomat, and judge who served as a United States Senator representing New York from 1959 until 1965. A member of the Republican Party, he also served in the ...

, a New York Republican, to charge that the three-member subcommittee, which included two pro-segregation Southern Democrats, was biased against Marshall and engaged in unjustifiable delay. The subcommittee held several hearings between May and August 1962; Marshall faced harsh questioning from the Southerners over what the scholar Howard Ball described as "marginal issues at best". After further delays from the subcommittee, the full Judiciary Committee bypassed it and, by an 11–4 vote on September 7, endorsed Marshall's nomination. Following five hours of floor debate, the full Senate confirmed him by a 56–14 vote on September 11, 1962.

On the Second Circuit, Marshall authored 98 majority opinions, none of which was reversed by the Supreme Court, as well as 8 concurrences and 12 dissents. He dissented when a majority held in the Fourth Amendment case of ''United States ex rel. Angelet v. Fay'' (1964) that the Supreme Court's 1961 decision in ''Mapp v. Ohio

''Mapp v. Ohio'', 367 U.S. 643 (1961), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the exclusionary rule, which prevents prosecutors from using Evidence (law), evidence in co ...

'' (which held that the exclusionary rule applied to the states) did not apply retroactively, writing that the judiciary was "not free to circumscribe the application of a declared constitutional right". In ''United States v. Wilkins'' (1964), he concluded that the Fifth Amendment's protection against double jeopardy applied to the states; in ''People of the State of New York v. Galamison'' (1965), he dissented from a ruling upholding the convictions of civil rights protesters at the New York World's Fair. Marshall's dissents indicated that he favored broader interpretations of constitutional protections than did his colleagues.

Solicitor General

When Archibald Cox resigned, PresidentLyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

nominated Marshall to take his place as Solicitor General—the individual responsible for arguing before the Supreme Court on behalf of the federal government. The nomination was widely viewed as a stepping stone to a Supreme Court appointment. Johnson pressured Southern senators not to obstruct Marshall's confirmation, and a hearing before a Senate subcommittee lasted only fifteen minutes; the full Senate confirmed him on August 11, 1965. As Solicitor General, Marshall won fourteen of the nineteen Supreme Court cases he argued. He later characterized the position as "the most effective job" and "maybe the best" job he ever had. Marshall argued in ''Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections

''Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections'', 383 U.S. 663 (1966), was a case in which the U.S. Supreme Court found that Virginia's poll tax was unconstitutional under the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. In the late 19th and ea ...

'' (1966) that conditioning the ability to vote on the payment of a poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments fr ...

was unlawful; in a companion case to ''Miranda v. Arizona

''Miranda v. Arizona'', 384 U.S. 436 (1966), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution restricts prosecutors from using a person's statements made in response to ...

'' (1966), he unsuccessfully maintained on behalf of the government that federal agents were not always required to inform arrested individuals of their rights. He defended the constitutionality of the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement ...

in ''South Carolina v. Katzenbach

''South Carolina v. Katzenbach'', 383 U.S. 301 (1966), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court that rejected a challenge from the state of South Carolina to the preclearance provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which required that ...

'' (1966) and ''Katzenbach v. Morgan

''Katzenbach v. Morgan'', 384 U.S. 641 (1966), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States regarding the power of Congress, pursuant to Section 5 of the 14th Amendment, to enact laws that enforce and interpret provisions ...

'' (1966), winning both cases.

Supreme Court nomination

In February 1967, Johnson nominatedRamsey Clark

William Ramsey Clark (December 18, 1927 – April 9, 2021) was an American lawyer, activist, and federal government official. A progressive, New Frontier liberal, he occupied senior positions in the United States Department of Justice under Presi ...

to be Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

. The nominee's father was Tom C. Clark

Thomas Campbell Clark (September 23, 1899June 13, 1977) was an American lawyer who served as the 59th United States Attorney General from 1945 to 1949 and as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1949 to 1967.

Clark ...

, an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Fearing that his son's appointment would create substantial conflicts of interest for him, the elder Clark announced his resignation from the Court. For Johnson, who had long desired to nominate a non-white justice, the choice of a nominee to fill the ensuing vacancy "was as easy as it was obvious", according to the scholar Henry J. Abraham

Henry Julian Abraham (August 25, 1921 – February 26, 2020) was a German-born American scholar on the judiciary and constitutional law. He was James Hart Professor of Government Emeritus at the University of Virginia. He was the author of 13 ...

. Although the President briefly considered selecting William H. Hastie

William Henry Hastie Jr. (November 17, 1904 – April 14, 1976) was an American lawyer, judge, educator, public official, and civil rights advocate. He was the first African American to serve as Governor of the United States Virgin Islands, as a ...

(an African-American appellate judge from Philadelphia) or a female candidate, he decided to choose Marshall. Johnson announced the nomination in the White House Rose Garden

The White House Rose Garden is a garden bordering the Oval Office and the West Wing of the White House in Washington, D.C., United States. The garden is approximately 125 feet long and 60 feet wide ( by , or about 684m²). It balances the Jacquel ...

on June 13, declaring that Marshall "deserves the appointment... I believe that it is the right thing to do, the right time to do it, the right man and the right place."

The public received the nomination favorably, and Marshall was praised by prominent senators from both parties. The Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations, a ...

held hearings for five days in July. Marshall faced harsh criticism from such senators as Mississippi's James O. Eastland

James Oliver Eastland (November 28, 1904 February 19, 1986) was an American attorney, plantation owner, and politician from Mississippi. A Democratic Party (United States), Democrat, he served in the United States Senate in 1941 and again from 1 ...

, North Carolina's Sam Ervin Jr., Arkansas's John McClellan, and South Carolina's Strom Thurmond

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902June 26, 2003) was an American politician who represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to 2003. Prior to his 48 years as a senator, he served as the 103rd governor of South Caro ...

, all of whom opposed the nominee's liberal jurisprudence. In what ''Time'' magazine characterized as a "Yahoo-type hazing", Thurmond asked Marshall over sixty questions about various minor aspects of the history of certain constitutional provisions. By an 11–5 vote on August 3, the committee recommended that Marshall be confirmed. On August 30, after six hours of debate, senators voted 69–11 to confirm Marshall to the Supreme Court. He took the constitutional oath of office on October 2, 1967, becoming the first African American to serve as a justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Supreme Court

Marshall remained on the Supreme Court for nearly twenty-four years, serving until his retirement in 1991. The Court to which he was appointed—the

Marshall remained on the Supreme Court for nearly twenty-four years, serving until his retirement in 1991. The Court to which he was appointed—the Warren Court

The Warren Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of the United States during which Earl Warren served as Chief Justice. Warren replaced the deceased Fred M. Vinson as Chief Justice in 1953, and Warren remained in office until ...

—had a consistent liberal majority, and Marshall's jurisprudence was similar to that of its leaders, Chief Justice Warren and Justice William J. Brennan Jr.

William Joseph "Bill" Brennan Jr. (April 25, 1906 – July 24, 1997) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1956 to 1990. He was the seventh-longest serving justice ...

Although he wrote few major opinions during this period due to his lack of seniority, he was typically in the majority. As a result of four Supreme Court appointments by President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

, however, the liberal coalition vanished. The Court under Chief Justice Warren Burger

Warren Earl Burger (September 17, 1907 – June 25, 1995) was an American attorney and jurist who served as the 15th chief justice of the United States from 1969 to 1986. Born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Burger graduated from the St. Paul Colleg ...

(the Burger Court) was not as conservative as some observers had anticipated, but the task of constructing liberal majorities case-by-case was left primarily to Brennan; Marshall's most consequential contributions to constitutional law came in dissent. The justice left much of his work to his law clerk

A law clerk or a judicial clerk is a person, generally someone who provides direct counsel and assistance to a lawyer or judge by researching issues and drafting legal opinions for cases before the court. Judicial clerks often play significant ...

s, preferring to determine the outcome of the case and then allow the clerks to draft the opinion themselves. He took umbrage at frequent claims that he did no work and spent his time watching daytime soap opera

A soap opera, or ''soap'' for short, is a typically long-running radio or television serial, frequently characterized by melodrama, ensemble casts, and sentimentality. The term "soap opera" originated from radio dramas originally being sponsored ...

s; according to Tushnet, who clerked for Marshall, the idea that he "was a lazy Justice uninterested in the Court's work... is wrong and perhaps racist". Marshall's closest colleague and friend on the Court was Brennan, and the two justices agreed so often that their clerks privately referred to them as "Justice Brennanmarshall". He also had a high regard for Warren, whom he described as "probably the greatest Chief Justice who ever lived".

Marshall consistently sided with the Supreme Court's liberal bloc. According to the scholar William J. Daniels: "His approach to justice was Warren Court–style legal realism

Legal realism is a naturalistic approach to law. It is the view that jurisprudence should emulate the methods of natural science, i.e., rely on empirical evidence. Hypotheses must be tested against observations of the world.

Legal realists be ...

... In his dissenting opinions he emphasized individual rights, fundamental fairness, equal opportunity and protection under the law, the supremacy of the Constitution as the embodiment of rights and privileges, and the Supreme Court's responsibility to play a significant role in giving meaning to the notion of constitutional rights." Marshall's jurisprudence was pragmatic and relied on his real-world experience as a lawyer and as an African American. He disagreed with the notion (favored by some of his conservative colleagues) that the Constitution should be interpreted according to the Founders' original understandings; in a 1987 speech commemorating the Constitution's bicentennial, he said:

Equal protection and civil rights

As the Court became increasingly conservative, Marshall found himself dissenting in numerous cases regarding racial discrimination. When the majority held in ''

As the Court became increasingly conservative, Marshall found himself dissenting in numerous cases regarding racial discrimination. When the majority held in ''Milliken v. Bradley

''Milliken v. Bradley'', 418 U.S. 717 (1974), was a significant Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court case dealing with the planned desegregation busing in the United States, desegregation busing of public school students ...

'' that a lower court had gone too far in ordering busing

Race-integration busing in the United States (also known simply as busing, Integrated busing or by its critics as forced busing) was the practice of assigning and transporting students to schools within or outside their local school districts in ...

to reduce racial imbalances between schools in Detroit, he dissented, criticizing his colleagues for what he viewed as a lack of resolve to implement desegregation even when faced with difficulties and public resistance. In a dissent in '' City of Memphis v. Greene'' that according to Tushnet "demonstrated his sense of the practical reality that formed the context for abstract legal issues", he argued that a street closure that made it more difficult for residents of an African-American neighborhood to reach a city park was unconstitutional because it sent "a plain and powerful symbolic message" to blacks that "that because of their race, they are to stay out of the all-white enclave... and should instead take the long way around". Marshall felt that affirmative action was both necessary and constitutional; in an opinion in ''Regents of the University of California v. Bakke

''Regents of the University of California v. Bakke'', 438 U.S. 265 (1978) involved a dispute of whether preferential treatment for minorities can reduce educational opportunities for whites without violating the Constitution. The case was a la ...

'', he commented that it was "more than a little ironic that, after several hundred years of class-based discrimination against Negroes, the Court is unwilling to hold that a class-based remedy for that discrimination is permissible". Dissenting in ''City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co.

''City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co.'', 488 U.S. 469 (1989), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court held that the minority set-aside program of Richmond, Virginia, which gave preference to minority business enterprises (MBE) in the ...

'', he rejected the majority's decision to strike down an affirmative-action program for government contractors, stating that he did "not believe that this Nation is anywhere close to eradicating racial discrimination or its vestiges".

Marshall's most influential contribution to constitutional doctrine was his "sliding-scale" approach to the Equal Protection Clause, which posited that the judiciary should assess a law's constitutionality by balancing its goals against its impact on groups and rights. Dissenting in '' Dandridge v. Williams'', a case in which the majority upheld Maryland's $250-a-month cap on welfare payments against claims that it was insufficient for large families, he argued that rational basis review

In U.S. constitutional law, rational basis review is the normal standard of review that courts apply when considering constitutional questions, including due process or equal protection questions under the Fifth Amendment or Fourteenth Amendment ...

was not appropriate in cases involving "the literally vital interests of a powerless minority". In what Cass Sunstein

Cass Robert Sunstein (born September 21, 1954) is an American legal scholar known for his studies of constitutional law, administrative law, environmental law, law and behavioral economics. He is also ''The New York Times'' best-selling author of ...

described as the justice's greatest opinion, Marshall dissented when the Court in ''San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez

''San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez'', 411 U.S. 1 (1973), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that San Antonio Independent School District's financing system, which was based on local property taxes, w ...

'' upheld a system in which local schools were funded mainly through property taxes, arguing that the policy (which meant that poorer school districts obtained less money than richer ones) resulted in unconstitutional discrimination. His dissent in ''Harris v. McRae

''Harris v. McRae'', 448 U.S. 297 (1980), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that states participating in Medicaid are not required to fund medically necessary abortions for which federal reimbursement was unavailable a ...

'', in which the Court upheld the Hyde Amendment's ban on the use of Medicaid

Medicaid in the United States is a federal and state program that helps with healthcare costs for some people with limited income and resources. Medicaid also offers benefits not normally covered by Medicare, including nursing home care and pers ...

funds to pay for abortions

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pregnan ...

, rebuked the majority for applying a "relentlessly formalistic catechism" that failed to take account of the amendment's "crushing burden on indigent women". Although Marshall's sliding-scale approach was never adopted by the Court as a whole, the legal scholar Susan Low Bloch comments that "his consistent criticism seems to have prodded the Court to somewhat greater flexibility".

Criminal procedure and capital punishment

Marshall supported the Warren Court's constitutional decisions on criminal law, and he wrote the opinion of the Court in ''Benton v. Maryland

''Benton v. Maryland'', 395 U.S. 784 (1969), is a Supreme Court of the United States decision concerning double jeopardy. ''Benton'' ruled that the Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Fifth Amendment In ...

'', which held that the Constitution's prohibition of double jeopardy applied to the states. After the retirements of Warren and Justice Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black (February 27, 1886 – September 25, 1971) was an American lawyer, politician, and jurist who served as a U.S. Senator from Alabama from 1927 to 1937 and as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1937 to 1971. A ...

, however, "Marshall was continually shocked at the refusal" of the Burger and Rehnquist Court

The Rehnquist Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of the United States during which William Rehnquist served as Chief Justice. Rehnquist succeeded Warren Burger as Chief Justice after the latter's retirement, and Rehnquist ...

s "to hold police and those involved in the criminal justice system responsible for acting according to the language and the spirit of fundamental procedural guarantees", according to Ball. He favored a strict interpretation of the Fourth Amendment's warrant requirement and opposed rulings that made exceptions to that provision; in ''United States v. Ross

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two fi ...

'', for instance, he indignantly dissented when the Court upheld a conviction that was based on evidence discovered during a warrantless search of containers that had been found in an automobile. Marshall felt strongly that the ''Miranda'' doctrine should be expanded and fully enforced. In cases involving the Sixth Amendment, he argued that defendants must have competent attorneys; dissenting in ''Strickland v. Washington

''Strickland v. Washington'', 466 U.S. 668 (1984), was a landmark Supreme Court case that established the standard for determining when a criminal defendant's Sixth Amendment right to counsel is violated by that counsel's inadequate performance ...

'', Marshall (parting ways with Brennan) rejected the majority's conclusion that defendants must prove prejudice in ineffective assistance of counsel cases.

Marshall fervently opposed capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

throughout his time on the Court, arguing that it was cruel and unusual and therefore unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment. He was the only justice with considerable experience defending those charged with capital crimes, and he expressed concern about the fact that injustices in death-penalty cases could not be remedied, often commenting: "Death is so lasting." In ''Furman v. Georgia

''Furman v. Georgia'', 408 U.S. 238 (1972), was a landmark criminal case in which the United States Supreme Court invalidated all then existing legal constructions for the death penalty in the United States. It was 5–4 decision, with each mem ...

'', a case in which the Court struck down the capital-punishment statutes that were in force at the time, Marshall wrote that the death penalty was "morally unacceptable to the people of the United States at this time in their history" and that it "falls upon the poor, the ignorant, and the underprivileged members of society". When the Court in ''Gregg v. Georgia

''Gregg v. Georgia'', ''Proffitt v. Florida'', ''Jurek v. Texas'', ''Woodson v. North Carolina'', and ''Roberts v. Louisiana'', 428 U.S. 153 (1976), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court. It reaffirmed the Court's acceptance of the use ...

'' upheld new death-penalty laws that required juries to consider aggravating

Aggravation, in law, is "any circumstance attending the commission of a crime or tort which increases its guilt or enormity or adds to its injurious consequences, but which is above and beyond the essential constituents of the crime or tort itself. ...

and mitigating circumstances

In criminal law, a mitigating factor, also known as an extenuating circumstance, is any information or evidence presented to the court regarding the defendant or the circumstances of the crime that might result in reduced charges or a lesser sente ...

, he dissented, describing capital punishment as a "vestigial savagery" that was immoral and violative of the Eighth Amendment. Afterwards, Marshall and Brennan dissented in every instance in which the Court declined to review a death sentence, filing more than 1,400 dissents that read: "Adhering to our views that the death penalty is in all circumstances cruel and unusual punishment prohibited by the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments, we would grant certiorari

In law, ''certiorari'' is a court process to seek judicial review of a decision of a lower court or government agency. ''Certiorari'' comes from the name of an English prerogative writ, issued by a superior court to direct that the record of ...

and vacate the death sentence in this case."

First Amendment

According to Ball, Marshall felt that the rights protected by theFirst Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

were the Constitution's most important principles and that they could be restricted only for extremely compelling reasons. In a 1969 opinion in ''Stanley v. Georgia

''Stanley v. Georgia'', 394 U.S. 557 (1969), was a U.S. Supreme Court decision that helped to establish an implied "right to privacy" in U.S. law in the form of mere possession of obscene materials.

The Georgia home of Robert Eli Stanley, a susp ...

'', he held that it was unconstitutional to criminalize the possession of obscene material. For the Court, he reversed the conviction of a Georgia man charged with possessing pornography, writing: "If the First Amendment means anything, it means that a State has no business telling a man, sitting alone in his own house, what books he may read or what films he may watch." In '' Amalgamated Food Employees Union Local 400 v. Logan Valley Plaza'', he wrote for the Court that protesters had the right to picket on private property that was open to the public—a decision that was effectively overruled (over Marshall's dissent) four years later in ''Lloyd Corporation v. Tanner''. He emphasized equality in his free speech opinions, writing in '' Chicago Police Dept. v. Mosley'' that "above all else, the First Amendment means that government has no power to restrict expression because of its messages, its ideas, its subject matter, or its content". Making comparisons to earlier civil rights protests, Marshall vigorously dissented in '' Clark v. Community for Creative Non-Violence'', a case in which the Court ruled that the government could forbid homeless individuals from protesting poverty by sleeping overnight in Lafayette Park; although Burger decried their claims as "frivolous" attempts to "trivialize" the Constitution, Marshall argued that the protesters were engaged in constitutionally protected symbolic speech Symbolic speech is a legal term in United States law used to describe actions that purposefully and discernibly convey a particular message or statement to those viewing it. Symbolic speech is recognized as being protected under the First Amendment ...

.

Marshall joined the majority in ''Texas v. Johnson

''Texas v. Johnson'', 491 U.S. 397 (1989), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in which the Court held, 5–4, that burning the American flag was protected speech under the First Amendment to the Constitution, as do ...

'' and ''United States v. Eichman

''United States v. Eichman'', 496 U.S. 310 (1990), was a United States Supreme Court case that invalidated a federal law against flag desecration as a violation of free speech under the First Amendment. It was argued together with the case ''Unite ...

'', two cases in which the Court held that the First Amendment protected the right to burn the American flag. He favored the total separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

, dissenting when the Court upheld in ''Lynch v. Donnelly

''Lynch v. Donnelly'', 465 U.S. 668 (1984), was a United States Supreme Court case challenging the legality of Christmas decorations on town property.

Background

Pawtucket, Rhode Island's annual Christmas display in the city's shopping district, c ...

'' a city's display of a nativity scene

In the Christianity, Christian tradition, a nativity scene (also known as a manger scene, crib, crèche ( or ), or in Italian language, Italian ''presepio'' or ''presepe'', or Bethlehem) is the special exhibition, particularly during the Christ ...

and joining the majority in ''Wallace v. Jaffree

''Wallace v. Jaffree'', 472 U.S. 38 (1985), was a United States Supreme Court case deciding on the issue of silent school prayer.

Background

An Alabama law authorized teachers to set aside one minute at the start of each day for a moment for ...

'' to strike down an Alabama law regarding prayer in schools. On the issue of the free exercise of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedom ...

, Marshall voted with the majority in ''Wisconsin v. Yoder

''Wisconsin v. Jonas Yoder'', 406 U.S. 205 (1972), is the case in which the United States Supreme Court found that Amish children could not be placed under compulsory education past 8th grade. The parents' fundamental right to freedom of religion ...

'' to hold that a school attendance law could not be constitutionally applied to the Amish

The Amish (; pdc, Amisch; german: link=no, Amische), formally the Old Order Amish, are a group of traditionalist Anabaptist Christian church fellowships with Swiss German and Alsatian origins. They are closely related to Mennonite churches ...

, and he joined Justice Harry Blackmun

Harry Andrew Blackmun (November 12, 1908 – March 4, 1999) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1970 to 1994. Appointed by Republican President Richard Nixon, Blac ...

's dissent when the Court in '' Employment Division v. Smith'' upheld a restriction on religious uses of peyote

The peyote (; ''Lophophora williamsii'' ) is a small, spineless cactus which contains psychoactive alkaloids, particularly mescaline. ''Peyote'' is a Spanish word derived from the Nahuatl (), meaning "caterpillar cocoon", from a root , "to gl ...

and curtailed ''Sherbert v. Verner

''Sherbert v. Verner'', 374 U.S. 398 (1963), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment required the government to demonstrate both a compelling interest and that the law in ...

''strict scrutiny

In U.S. constitutional law, when a law infringes upon a fundamental constitutional right, the court may apply the strict scrutiny standard. Strict scrutiny holds the challenged law as presumptively invalid unless the government can demonstrate th ...

standard. In the view of J. Clay Smith Jr.

John Clay Smith Jr. (April 15, 1942 – February 15, 2018) was a lawyer, author, and American educator.

Smith was born in Omaha, Nebraska. He graduated from Creighton University in 1964. He received his master's and doctorate's degree from Geo ...

and Scott Burrell, the justice was "an unyielding supporter of civil liberties", whose "commitment to the values of the First Amendment was enhanced from actually realizing the historical consequences of being on the weaker and poorer side of power".

Privacy

In Marshall's view, the Constitution guaranteed to all citizens theright to privacy

The right to privacy is an element of various legal traditions that intends to restrain governmental and private actions that threaten the privacy of individuals. Over 150 national constitutions mention the right to privacy. On 10 December 1948 ...

; he felt that although the Constitution nowhere mentioned such a right expressly, it could be inferred from various provisions of the Bill of Rights. He joined the majority in ''Eisenstadt v. Baird

''Eisenstadt v. Baird'', 405 U.S. 438 (1972), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that established the right of unmarried people to possess contraception on the same basis as married couples.

The Court struck down a Massachusetts la ...

'' to strike down a statute that prohibited the distribution or sale of contraceptives

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

to unmarried persons, dissented when the Court in ''Bowers v. Hardwick

''Bowers v. Hardwick'', 478 U.S. 186 (1986), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that upheld, in a 5–4 ruling, the constitutionality of a Georgia sodomy law criminalizing oral and anal sex in private between consenting adults ...

'' upheld an anti-sodomy law, and dissented from the majority's decision in '' Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health'' that the Constitution did not protect an unconditional right to die

The right to die is a concept based on the opinion that human beings are entitled to end their life or undergo voluntary euthanasia. Possession of this right is often understood that a person with a terminal illness, incurable pain, or without t ...

. On the issue of abortion rights, the author Carl T. Rowan

Carl Thomas Rowan (August 11, 1925 – September 23, 2000) was a prominent American journalist, author and government official who published columns syndicated across the U.S. and was at one point the highest ranking African American in the United ...

comments that "no justice ever supported a woman's right to choice as uncompromisingly as Marshall did". He joined Blackmun's opinion for the Court in ''Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States conferred the right to have an abortion. The decision struck down many federal and st ...

'', which held that the Constitution protected a woman's right to have an abortion, and he consistently voted against state laws that sought to limit that right in cases such as '' Maher v. Roe'', '' H. L. v. Matheson'', '' Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health'', '' Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists'', and ''Webster v. Reproductive Health Services

''Webster v. Reproductive Health Services'', 492 U.S. 490 (1989), was a Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court decision on upholding a Missouri law that imposed restrictions on the use of state funds, facilities, and employ ...

''.

Other topics

During his service on the Supreme Court, Marshall participated in over 3,400 cases and authored 322 majority opinions. He was a member of the unanimous majority in ''United States v. Nixon

''United States v. Nixon'', 418 U.S. 683 (1974), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case that resulted in a unanimous decision against President Richard Nixon, ordering him to deliver tape recordings and other subpoenaed materials to a ...

'' that rejected President Nixon's claims of absolute executive privilege. Marshall wrote several influential decisions in the fields of corporate law and securities law

Securities regulation in the United States is the field of U.S. law that covers transactions and other dealings with securities. The term is usually understood to include both federal and state-level regulation by governmental regulatory agencies, ...

, including a frequently-cited opinion regarding materiality in '' TSC Industries, Inc. v. Northway, Inc.'' His opinions involving personal jurisdiction

Personal jurisdiction is a court's jurisdiction over the ''parties'', as determined by the facts in evidence, which bind the parties to a lawsuit, as opposed to subject-matter jurisdiction, which is jurisdiction over the ''law'' involved in the ...

, such as ''Shaffer v. Heitner

''Shaffer v. Heitner'', 433 U.S. 186 (1977), is a United States corporate law case in which the Supreme Court of the United States established that a defendant's ownership of stock in a corporation incorporated within a state, without more, is ins ...

'', were pragmatic and de-emphasized the importance of state boundaries. According to Tushnet, Marshall was "the Court's liberal specialist in Native American law

Native may refer to:

People

* Jus soli, citizenship by right of birth

* Indigenous peoples, peoples with a set of specific rights based on their historical ties to a particular territory

** Native Americans (disambiguation)

In arts and enterta ...

"; he endeavored to protect Native Americans from regulatory action on the part of the states. He favored a rigid interpretation of procedural requirements, saying in one case that "rules mean what they say"—a position that in Tushnet's view was motivated by the justice's "traditionalist streak".

Personal life

Marshall wed Vivian "Buster" Burey on September 4, 1929, while he was a student at Lincoln University. They remained married until her death from cancer in 1955. Marshall married Cecilia "Cissy" Suyat, an NAACP secretary, eleven months later; they had two children: Thurgood Jr. and

Marshall wed Vivian "Buster" Burey on September 4, 1929, while he was a student at Lincoln University. They remained married until her death from cancer in 1955. Marshall married Cecilia "Cissy" Suyat, an NAACP secretary, eleven months later; they had two children: Thurgood Jr. and John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

. (Thurgood Jr. became an attorney and worked in the Clinton administration

Bill Clinton's tenure as the 42nd president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1993, and ended on January 20, 2001. Clinton, a Democrat from Arkansas, took office following a decisive election victory over Re ...

, and John directed the U.S. Marshals Service

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforcem ...

and served as Virginia's secretary of public safety.) Marshall was an active member of the Episcopal Church and served as a delegate to its 1964 convention, walking out after a resolution to recognize a right to disobey immoral segregation laws was voted down. He was a Prince Hall Mason, attending meetings and participating in rituals. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor

Sandra Day O'Connor (born March 26, 1930) is an American retired attorney and politician who served as the first female associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1981 to 2006. She was both the first woman nominated and th ...

, who served with Marshall on the Supreme Court for a decade, wrote that "it was rare during our conference deliberations that he would not share an anecdote, a joke or a story"; although O'Connor initially treated the stories as "welcome diversions", she later "realized that behind most of the anecdotes was a relevant legal point".

Retirement, later life, and death

Marshall did not wish to retire—he frequently said "I was appointed to a life term, and I intend to serve it"—but he had been in ill health for many years, and Brennan's retirement in 1990 left him unhappy and isolated on the Court. The 82-year-old justice announced on June 27, 1991, that he would retire. When asked at a

Marshall did not wish to retire—he frequently said "I was appointed to a life term, and I intend to serve it"—but he had been in ill health for many years, and Brennan's retirement in 1990 left him unhappy and isolated on the Court. The 82-year-old justice announced on June 27, 1991, that he would retire. When asked at a press conference

A press conference or news conference is a media event in which notable individuals or organizations invite journalists to hear them speak and ask questions. Press conferences are often held by politicians, corporations, non-governmental organ ...

what was wrong with him that would cause him to leave the Court, he replied: "What's ''wrong'' with me? I'm old. I'm getting old and coming apart!" President George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushSince around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; pr ...

(whom Marshall loathed) nominated Clarence Thomas