Julines Herring on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Julines Herring (1582–1644/5) was a

/ref> or ''Flambere-Mayre''. He was a son of Richard Herring, a prominent local politician of

/ref> The Herring family had branches in Shropshire and the 1623 heraldic visitation of Shropshire named the parent Warwickshire branch as being "of Owsley iuxta Couentry" in

It seems that the Herring family returned to Coventry while Julines was very young. He was schooled initially at the small border village of

It seems that the Herring family returned to Coventry while Julines was very young. He was schooled initially at the small border village of

Herring was recommended for the post at Calke by

Herring was recommended for the post at Calke by

/ref> In his early years he was both friend and protégé of Hildersham, part of a generation of younger disciples that included Simeon Ashe and Hildersham's own son, Samuel. Herring was not the first member of Hilderham's circle appointed to Calke: Robert Bainbridge, the patron, had earlier installed George More, a close associate of Hildersham and of John Darrell. During the 1590s More took part in the religious exercises of the Hildersham circle, which included fasting, prayer, lectures and fellowship, and supported Darrell in the highly controversial work of exorcism. Clarke considered Calke a relatively secure base for Herring because it was a peculiar jurisdiction exempt from episcopal authority, as well as bringing the support of a sympathetic patron. CCEd, citing a 1772 reference, makes clear that Calke was a donative, rather than a peculiar. '' Magna Britannia'', published in 1817, numbered Calke among nine Derbyshire parishes that were donatives before the Victorian abolition of these institutions. In a donative the patron had the right to make an appointment to the

''Bainbridge, Robert (d.c.1623), of Derby and Calke, Derbys.''

/ref> from Richard Wennesley, a local landowner who had recusant affinities. Bainbridge probably took on the opportunity and obligation to provide a minister in order to secure freedom of worship for himself, as he had several other houses and seems to have had his main residence in Derby. He was a militant Protestant, three times MP for Although Calke was a very small settlement, then as now, it seems to have formed an ideal base for Herring's ministry, which was primarily one of

Although Calke was a very small settlement, then as now, it seems to have formed an ideal base for Herring's ministry, which was primarily one of

/ref> Lloyd was held in no great regard as a preacher and was paid £5 to read

/ref> It was Rowley who made the initial approach to Herring and acted throughout as his "faithful friend." It seems that he initially accommodated the Herring family in his own mansion. Rowley was a member of Shrewsbury's powerful Drapers' Company and Hunt was its warden.Coulton, p. 79. The company's hall was vacant and it was probably they who prevailed on the members to lease it to Herring for £4 annually, the company reserving the right to use it for meetings but agreeing to pay for repairs.Owen and Blakeway, p. 279-80, note 4.

/ref> Herring was obliged to preach twice weekly: on Tuesday morning and at 1 pm on Sunday. This was to avoid offending the other clergy in the town by poaching their congregations. In addition, he repeated the Sunday sermon that evening, alternating between the houses of three powerful Puritan merchants: Edward Jones, George Wright and Rowley. A specimen of his preaching, showing his Herring was subject to attack and controversy on both sides, conservative and radical, during his preaching ministry at Shrewsbury. As early as 1620, just after Thomas Morton became Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, Herring was reported to the authorities for failure to use the prayer book and to receive or administer the sacraments. Morton had clashed with Puritan clergy in his former Diocese of Chester over ceremonial practices and the Declaration of Sports. His response had been

Herring was subject to attack and controversy on both sides, conservative and radical, during his preaching ministry at Shrewsbury. As early as 1620, just after Thomas Morton became Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, Herring was reported to the authorities for failure to use the prayer book and to receive or administer the sacraments. Morton had clashed with Puritan clergy in his former Diocese of Chester over ceremonial practices and the Declaration of Sports. His response had been

/ref> It seems that he continued to conduct private fasts and Bible expositions even during periods when his public ministry was made impossible. These would have been held in Draper's Hall, which was his own home.Coulton, p. 82. Opposition to Herring coalesced around Peter Studley, who was incumbent or Herring continued to make and maintain links with moderate Presbyterian preachers in the region and beyond, gaining recognition for Shrewsbury as the centre of a Puritan network. He brought his brother-in-law, Robert Nicolls of Wrenbury, and Thomas Pierson of

Herring continued to make and maintain links with moderate Presbyterian preachers in the region and beyond, gaining recognition for Shrewsbury as the centre of a Puritan network. He brought his brother-in-law, Robert Nicolls of Wrenbury, and Thomas Pierson of

/ref> widow from 1626 of the noted judge Sir Edward Bromley. During the 1630s the bitterness of religious conflict at Shrewsbury intensified to a pitch that brought national attention and made Herring's position precarious. Bishop Wright's visitation of the town provided Studley with an opportunity for a triumphal reading of ordinances on the decoration of churches, but also for a denunciation of his opponents that revealed the depth of opposition. Herring's supporters, Rowley and Wright, were now joined by

During the 1630s the bitterness of religious conflict at Shrewsbury intensified to a pitch that brought national attention and made Herring's position precarious. Bishop Wright's visitation of the town provided Studley with an opportunity for a triumphal reading of ordinances on the decoration of churches, but also for a denunciation of his opponents that revealed the depth of opposition. Herring's supporters, Rowley and Wright, were now joined by

Herring sought a home first in Wrenbury,

Herring sought a home first in Wrenbury,

This was a time of indecision for Herring. He received invitations to leave for

This was a time of indecision for Herring. He received invitations to leave for

/ref> His reservations may have been connected with a letter Herring and thirteen other Puritan clerics sent in 1637 to ministers in New England, which raised the alarm about separatism among them. However, towards the end of 1636, some friends put forward his name to John Rulice or Rulitius, then a pastorSteven, p. 279.

/ref> of the

/ref> He moved in with a friend, Whittaker, pending the arrival of his family and his remaining property. Herring delivered his first sermon on : "The earth is the Lord's, and the fulness thereof; the world, and they that dwell therein." This met with great approval, securing his acceptance by the congregation. This paved the way for ratification by the Consistory of

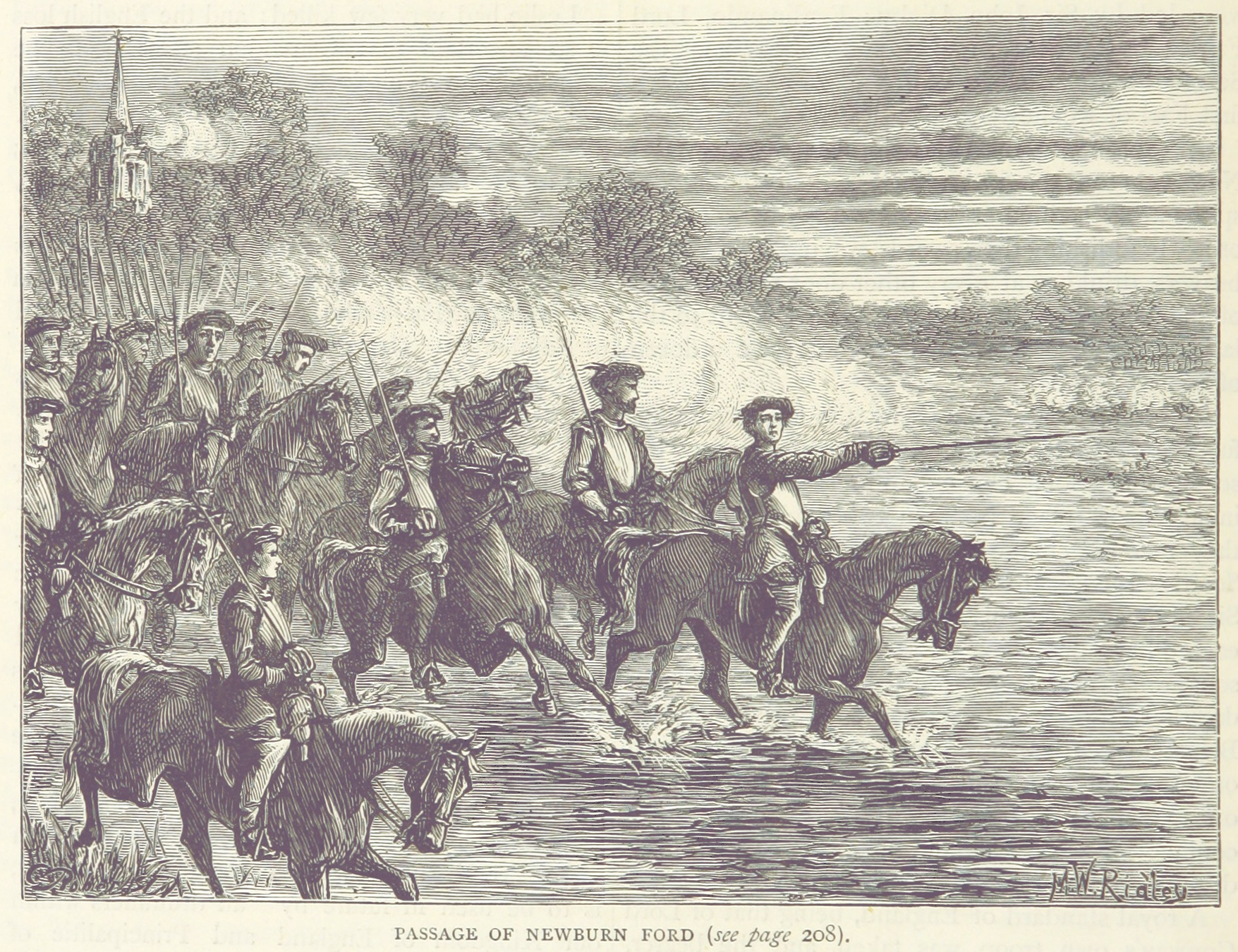

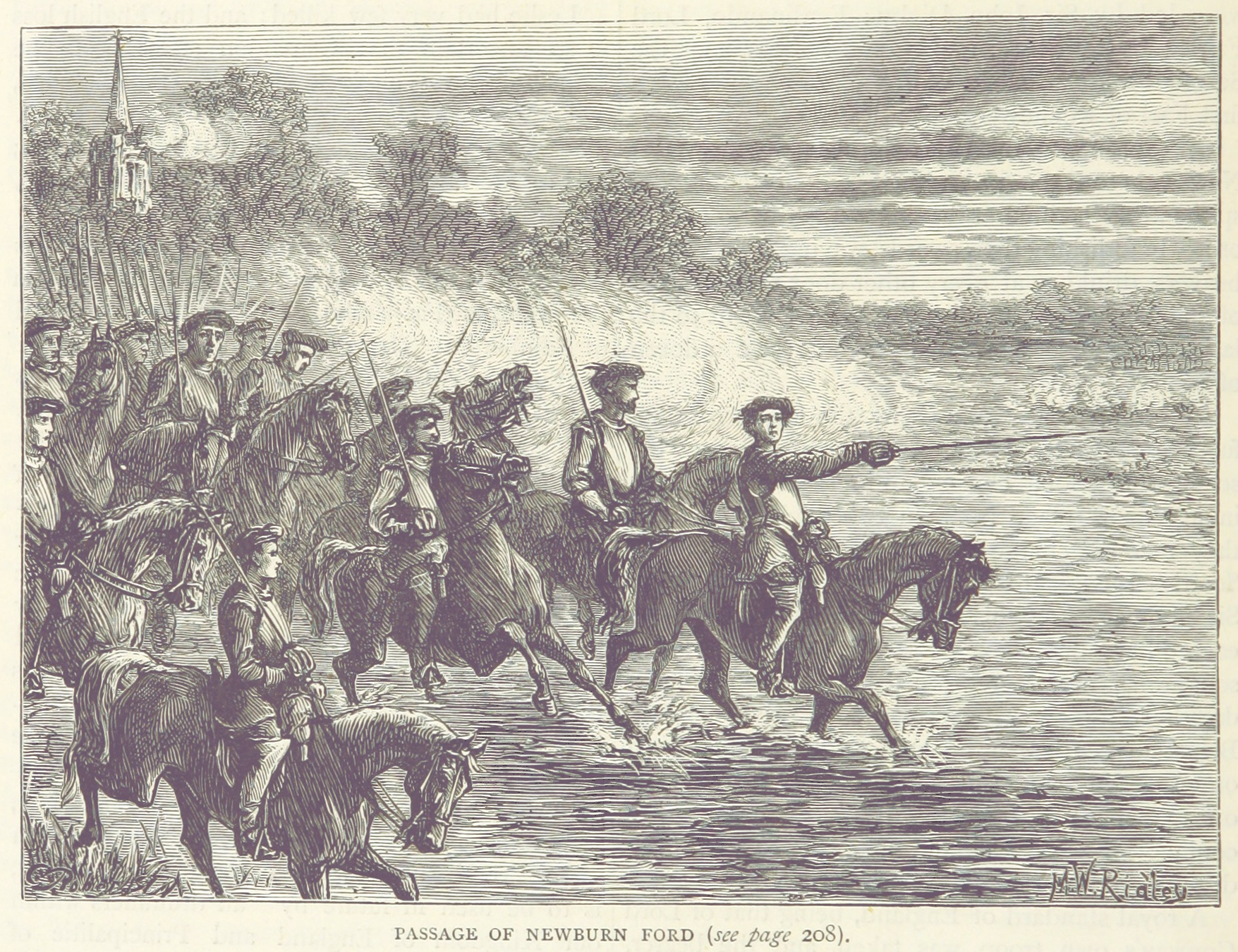

/ref> He continued to stress a middle position, troubled by the many fissile Independent and In 1640 he welcomed the invasion of northern England by a Scottish

In 1640 he welcomed the invasion of northern England by a Scottish

Herring seems to have entered into a long illness and he was clearly troubled by periods of doubt as well as suffering, in the language of the time, assaults by Satan. His last reported words, after such a period of uncertainty, were: "He is overcome, overcome, through the strength of my Lord and only Saviour Iesus, unto whom I am now going to keep a Sabbath in glory." He died the following morning, given by Clarke as Sunday 28 March 1644. The date is widely but not universally accepted. William Steven in 1833 calculated Herring's ministry as lasting eight years from 1637, which implies he died in 1645. Coulton in 2010 noted that the corporation of Shrewsbury wrote to Herring again asking him to return, apparently in 1645, some months after the town fell to Parliamentarian forces. The corporation's invitation seems inconsistent with a death in 1644. Coulton is noncommital about the actual date, but points out that the register of the English Reformed Church shows he was certainly dead by 18 May 1645. The parishioners of Chad's parish in Shrewsbury subsequently switched their attention to Thomas Paget, Herring's co-pastor at Amsterdam, and in 1646 elected him their minister.Coulton, p. 106. Herring's will was proved by Christian, his widow on 26 March 1646.

Samuel Clarke's biography of Herring, part of a set of Puritan studies appended to his ''Generall Martyrologie'', appeared as early as 1651, under the

Herring seems to have entered into a long illness and he was clearly troubled by periods of doubt as well as suffering, in the language of the time, assaults by Satan. His last reported words, after such a period of uncertainty, were: "He is overcome, overcome, through the strength of my Lord and only Saviour Iesus, unto whom I am now going to keep a Sabbath in glory." He died the following morning, given by Clarke as Sunday 28 March 1644. The date is widely but not universally accepted. William Steven in 1833 calculated Herring's ministry as lasting eight years from 1637, which implies he died in 1645. Coulton in 2010 noted that the corporation of Shrewsbury wrote to Herring again asking him to return, apparently in 1645, some months after the town fell to Parliamentarian forces. The corporation's invitation seems inconsistent with a death in 1644. Coulton is noncommital about the actual date, but points out that the register of the English Reformed Church shows he was certainly dead by 18 May 1645. The parishioners of Chad's parish in Shrewsbury subsequently switched their attention to Thomas Paget, Herring's co-pastor at Amsterdam, and in 1646 elected him their minister.Coulton, p. 106. Herring's will was proved by Christian, his widow on 26 March 1646.

Samuel Clarke's biography of Herring, part of a set of Puritan studies appended to his ''Generall Martyrologie'', appeared as early as 1651, under the

Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

clergyman within the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

who served in Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

and at Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

. Ejected from his positions for nonconformity, he became a minister serving the English-speaking community in the Netherlands. He was a staunch proponent of Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

and an opponent of separatism.

Origins

Herring was born inWales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

at Llanbrynmair

Llanbrynmair () is a village, community and electoral ward in Montgomeryshire, Powys, on the A470 road between Caersws and Machynlleth. Llanbrynmair, in area, is the second largest in Powys. In 2011, it had a population of 920.

Description

The co ...

, Montgomeryshire

Montgomeryshire, also known as ''Maldwyn'' ( cy, Sir Drefaldwyn meaning "the Shire of Baldwin's town"), is one of thirteen historic counties of Wales, historic counties and a former administrative county of Wales. It is named after its county tow ...

, often rendered in older sources in Anglicised forms, e.g. ''Flamber-Mayre'',Brook, p. 489./ref> or ''Flambere-Mayre''. He was a son of Richard Herring, a prominent local politician of

Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its ...

, who served at various times as mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well a ...

and sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

.Clarke, p. 462./ref> The Herring family had branches in Shropshire and the 1623 heraldic visitation of Shropshire named the parent Warwickshire branch as being "of Owsley iuxta Couentry" in

Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon an ...

, which seems to be the modern Allesley, a parish that was broken into smaller parts in Victorian times. St Andrew's Church, serving Allesley Green

Allesley Green is a modern suburb of Coventry in the West Midlands, England, within the civil parish of Allesley.

The suburb lies west of the A45 road and is approximately west-northwest of Coventry city centre. Most of the housing dates from ...

and Eastern Green on the eastern edge of Coventry, claims Pond Farm as the former local residence of Julines Herring.

Education and early life

It seems that the Herring family returned to Coventry while Julines was very young. He was schooled initially at the small border village of

It seems that the Herring family returned to Coventry while Julines was very young. He was schooled initially at the small border village of More, Shropshire

More is a small village and civil parish in Shropshire, England.

It lies near the border with Wales and the nearest town is Bishop's Castle.

There is a parish church in the village. The civil parish extends greatly to the north of the village, ...

by a Mr Perkin, a close relative of his mother. Samuel Clarke, whose 1651 account is the basis for all later biographers, thought that it was from Perkin at More that Herring "learned the Principles of Religion." Clarke describes Perkin as a minister at ''More-chappel'' and these details have generally been accepted at face value. However, the Clergy of the Church of England database

The Clergy of the Church of England database (CCEd) is an online database of clergy of the Church of England between 1540 and 1835.

The database project began in 1999 with funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, and is ongoing as a ...

lists More as a parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in community activities, ...

within the Diocese of Hereford, not as a chapelry. Eyton, the pioneering historian of Shropshire, considered that More probably began as a chapelry of Lydbury North but "became independent, at a period which the earliest Records fail to reach." CCEd does list some clergy at More in the 1580s and Perkin is not among them, although the database cannot be exhaustive. It does not note any parish school at More but there was one at nearby Lydbury, although records of staff seem to start only with the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

. The older Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

avers that Perkin was a minister at ''Morechurch'': there is a Churchmoor, further east, in Lydbury North parish, but it is a hamlet with no chapel.

Herring then moved to the family home at Coventry, where he attended the Free Grammar School

Free Grammar Schools were schools which usually operated under the jurisdiction of the church in pre-modern England. Education had long been associated with religious institutions since a Cathedral grammar school was established at Canterbury unde ...

. Clarke credits his academic progress there to the then headmaster, whom he names as Reverend Master Tovey. Even as a schoolboy he was noted for his piety. Clarke credits him with an early interest and delight in the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

passages that deal with faith and repentance – themes typically of great concern to Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

s. On play days, he and a few friends engaged in prayer and religious exercises before going out.

In May 1600 Herring was admitted as a scholar to Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge

Sidney Sussex College (referred to informally as "Sidney") is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England. The College was founded in 1596 under the terms of the will of Frances Sidney, Countess of Sussex (1531–1589), wife ...

, then a new, specifically Protestant institution. University records show he graduated BA in the academic year 1603-4: Clarke thought Herring returned to Coventry as a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

. There he studied Divinity

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.divine

with the encouragement of Humphrey Fenn, a noted advocate of Presbyterianism and formerly a client of Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, (24 June 1532 – 4 September 1588) was an English statesman and the favourite of Elizabeth I from her accession until his death. He was a suitor for the queen's hand for many years.

Dudley's youth was ov ...

. Fenn had been suspended from his ministry since 1590 for his activities within a Warwickshire classis within the Church of England and had not regained his vicarage of Holy Trinity Church, Coventry

Holy Trinity Church, Coventry, is a parish church of the Church of England in Coventry City Centre, West Midlands, England.

Above the chancel arch is an impressive Doom wall-painting.

History

The church dates from the 12th century and is t ...

. Herring, however, seems to have found opportunities to preach, winning considerable approval.

Calke

Herring was approaching the age to take up a parish ministry of his own, but this requiredordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorization, authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominational ...

. Number 36 of the Book of Canons, confirmed by the Convocations of Canterbury and York

The Convocations of Canterbury and York are the synodical assemblies of the bishops and clergy of each of the two provinces which comprise the Church of England. Their origins go back to the ecclesiastical reorganisation carried out under Arc ...

in 1604 and 1606 respectively, demanded that all candidates for ordination take a three-fold oath, accepting the royal supremacy, the Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

and the Thirty-Nine Articles

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (commonly abbreviated as the Thirty-nine Articles or the XXXIX Articles) are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the ...

. The subscription book of the Diocese of Coventry and Lichfield, which covered the area in Herring both lived and sought a living, summarised the oath as:

The king is the only supreme governor under God of all things spiritual as well as temporal: the Book of Common Prayer, with the ordering of bishops priests and deacons, contains nothing contrary to the word of God: the Articles of Religion (1562) are agreeable to the word of God.Herring circumvented the requirement by securing ordination from an Irish bishop then visiting London. He was accompanied in this by other young Puritan men, including John Ball, a friend who was tutor to the children of Catherine and Robert Cholmondley. Only after the ordination were the pair able to take up their first ecclesiastical appointments: Ball as curate of Whitmore in

Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

; Herring as preacher at Calke

Calke is a small village and civil parish in the South Derbyshire district of Derbyshire, England. It includes the historic house Calke Abbey, a National Trust property, although the main entrance to its grounds is from the neighbouring villag ...

in Derbyshire.

Herring was recommended for the post at Calke by

Herring was recommended for the post at Calke by Arthur Hildersham

Arthur Hildersham (1563–1632) was an English clergyman, a Puritan and nonconforming preacher.

Life

Arthur Hildersham was born at Stetchworth, and brought up as a Roman Catholic. He was educated in Saffron Walden and at Christ's College, Cam ...

, the vicar of Ashby-de-la-Zouch

Ashby-de-la-Zouch, sometimes spelt Ashby de la Zouch () and shortened locally to Ashby, is a market town and civil parish in the North West Leicestershire district of Leicestershire, England. The town is near to the Derbyshire and Staffordshire ...

, which was close by, although in Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ; postal abbreviation Leics.) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East Midlands, England. The county borders Nottinghamshire to the north, Lincolnshire to the north-east, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire t ...

.Clarke, p. 463./ref> In his early years he was both friend and protégé of Hildersham, part of a generation of younger disciples that included Simeon Ashe and Hildersham's own son, Samuel. Herring was not the first member of Hilderham's circle appointed to Calke: Robert Bainbridge, the patron, had earlier installed George More, a close associate of Hildersham and of John Darrell. During the 1590s More took part in the religious exercises of the Hildersham circle, which included fasting, prayer, lectures and fellowship, and supported Darrell in the highly controversial work of exorcism. Clarke considered Calke a relatively secure base for Herring because it was a peculiar jurisdiction exempt from episcopal authority, as well as bringing the support of a sympathetic patron. CCEd, citing a 1772 reference, makes clear that Calke was a donative, rather than a peculiar. '' Magna Britannia'', published in 1817, numbered Calke among nine Derbyshire parishes that were donatives before the Victorian abolition of these institutions. In a donative the patron had the right to make an appointment to the

benefice

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

without reference to the ordinary

Ordinary or The Ordinary often refer to:

Music

* ''Ordinary'' (EP) (2015), by South Korean group Beast

* ''Ordinary'' (Every Little Thing album) (2011)

* "Ordinary" (Two Door Cinema Club song) (2016)

* "Ordinary" (Wayne Brady song) (2008)

* ...

– in this case the local diocesan bishop. The church and the incumbent were exempt from ordinary jurisdiction: in a peculiar there is an ordinary jurisdiction but it does not belong to the local bishop. Calke church was part of Calke manor

Manor may refer to:

Land ownership

*Manorialism or "manor system", the method of land ownership (or "tenure") in parts of medieval Europe, notably England

*Lord of the manor, the owner of an agreed area of land (or "manor") under manorialism

*Man ...

– a former monastic estate that passed into lay hands through the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Although later named Calke Abbey, it had actually been a very small Augustinian Augustinian may refer to:

*Augustinians, members of religious orders following the Rule of St Augustine

*Augustinianism, the teachings of Augustine of Hippo and his intellectual heirs

*Someone who follows Augustine of Hippo

* Canons Regular of Sain ...

priory, which was absorbed as a mere cell into its own daughter house, Repton Priory: under the founder's terms, the church had been given to the canons on condition they supply it with a priest. Robert Bainbridge bought the Calke estate in 1582M. R. P., P.W. Hasler (ed)''Bainbridge, Robert (d.c.1623), of Derby and Calke, Derbys.''

/ref> from Richard Wennesley, a local landowner who had recusant affinities. Bainbridge probably took on the opportunity and obligation to provide a minister in order to secure freedom of worship for himself, as he had several other houses and seems to have had his main residence in Derby. He was a militant Protestant, three times MP for

Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby gai ...

, who was imprisoned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

during March 1587 after he had demanded the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

and supported Anthony Cope's proposal for a radical reform of Church government: he and his friends made the mistake of continuing to argue outside the chamber of the House of Commons, where they were not protected by parliamentary privilege

Parliamentary privilege is a legal immunity enjoyed by members of certain legislatures, in which legislators are granted protection against civil or criminal liability for actions done or statements made in the course of their legislative duties. ...

.

Although Calke was a very small settlement, then as now, it seems to have formed an ideal base for Herring's ministry, which was primarily one of

Although Calke was a very small settlement, then as now, it seems to have formed an ideal base for Herring's ministry, which was primarily one of preaching

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. El ...

. Clarke remarks that "God was pleased to set a broad scale to his Ministry." A clear and powerful preacher, he drew an audience from up to twenty towns and villages, with Sunday congregations in good weather so large that many were forced to cluster around the windows to hear him. Some brought picnics and made a day of it, while others bought refreshments from the "threepenny ordinary" provided for strangers. The impact of his preaching on the region was increased by the practice of returning home in groups, singing psalms and discussing the sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. El ...

. Clarke thought that the effectiveness of Herring's preaching as part of the Hildersham circle was proved by the very high retention of Puritan converts in the region, who remained with the cause through the "broken dividing times" that followed: presumably meaning the period of Thorough or absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

, the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

and the Regicide. Herring seems to have had a profound influence over Simeon Ashe, later a moderate Presbyterian preacher and an intimate of important parliamentarian leaders, including Robert Greville, 2nd Baron Brooke

Robert Greville, 2nd Baron Brooke (May 1607 – 4 March 1643) was a radical Puritan activist and leading member of the opposition to Charles I of England prior to the outbreak of the First English Civil War in August 1642. Appointed Roundhead, Pa ...

and Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester. Herring took the opportunity of a relatively stable period in his life to marry and start a family. His wife was Christian Gellibrand. The match was remembered in Puritan hagiography as particularly happy and mutually-supportive.

Herring's ministry at Calke seems to have lasted until 1618. Clarke thought he was "forced from thence for Nonconformity by the Prelatical power, being informed against by ill-affected men." He gives no details of how Herring could be removed from a donative. Barbara Coulton, a recent historian of Shrewsbury during this the period, gives 1617 as the year Herring was recruited by William Rowley of Shrewsbury,Coulton, p. 75. suggesting that he was attracted by a more influential post rather than driven out of Calke. This is supported by the baptism of Christian, a daughter of Herring, at St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury

St Chad's Church occupies a prominent position in Shrewsbury, the county town of Shropshire. The current church building was built in 1792, and with its distinctive round shape and high tower it is a well-known landmark in the town. It faces Th ...

as early as 1 February 1618. Herring's patron Bainbridge must by this time have been elderly, as he first sat in the House of Commons in 1571. He may have been in financial difficulties: although he had a vault prepared for his burial at Calke, he sold the estate only three years after Herring's departure and died before July 1623.

Shrewsbury

In 1618 Herring took up residence in Shrewsbury, at the invitation of the corporation, as lecturer at St Alkmund's Church. This was not an incumbency: the vicar of St Alkmund's throughout Herring's time in Shrewsbury was Thomas Lloyd, who had been appointed in 1607.Owen and Blakeway, p. 279./ref> Lloyd was held in no great regard as a preacher and was paid £5 to read

Morning Prayer Morning Prayer may refer to:

Religion

*Prayers in various traditions said during the morning

* Morning Prayer (Anglican), one of the two main Daily Offices in the churches of the Anglican Communion

* In Roman Catholicism:

** Morning offering of C ...

.Coulton, p. 78. Herring's lectureship did not require an oath before the bishop, as it was privately funded by a £20 annuity. This was provided by Rowland Heylyn, a merchant of Welsh ancestry, educated at Shrewsbury School

Shrewsbury School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13 –18) in Shrewsbury.

Founded in 1552 by Edward VI by Royal Charter, it was originally a boarding school for boys; girls have been admitted into the ...

and a former parishioner of St Alkmund's, who had become immensely wealthy and powerful in the Worshipful Company of Ironmongers in London. Heylyn had two sisters living in Shrewsbury, Ann and Eleanor, who were married respectively to John Nicholls and Richard Hunt, powerful local politicians who were associates of William Rowley, described by Clarke as "a wise religious man."Clarke, p. 464./ref> It was Rowley who made the initial approach to Herring and acted throughout as his "faithful friend." It seems that he initially accommodated the Herring family in his own mansion. Rowley was a member of Shrewsbury's powerful Drapers' Company and Hunt was its warden.Coulton, p. 79. The company's hall was vacant and it was probably they who prevailed on the members to lease it to Herring for £4 annually, the company reserving the right to use it for meetings but agreeing to pay for repairs.Owen and Blakeway, p. 279-80, note 4.

/ref> Herring was obliged to preach twice weekly: on Tuesday morning and at 1 pm on Sunday. This was to avoid offending the other clergy in the town by poaching their congregations. In addition, he repeated the Sunday sermon that evening, alternating between the houses of three powerful Puritan merchants: Edward Jones, George Wright and Rowley. A specimen of his preaching, showing his

hermeneutic

Hermeneutics () is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts. Hermeneutics is more than interpretative principles or methods used when immediate c ...

method at the service of his Puritan audience, runs:

:: ''All are yours.''

Yours! Whose meaneth the apostle by ''yours''? The Christian Corinths, to whome this epistle was directed, and those words. And what meaneth hee by the word ''all''. The verse itself shewes you. "Whether Paul, or Apollos, or Cephas, or the world, – or life, or death, or things present, or things to come, ''All are yours.''" And the expression is of a further latitude, v. 21. for all ''things'' are yours. All things therefore are the true Christian's. This is the truth that I am to teach you. Therefore, without any further coherence of these words with the former, or resolving the text into parts, (which is the ordinarie course of ministers,) I must fall upon this; – all things are the true Christian's.

Herring was subject to attack and controversy on both sides, conservative and radical, during his preaching ministry at Shrewsbury. As early as 1620, just after Thomas Morton became Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, Herring was reported to the authorities for failure to use the prayer book and to receive or administer the sacraments. Morton had clashed with Puritan clergy in his former Diocese of Chester over ceremonial practices and the Declaration of Sports. His response had been

Herring was subject to attack and controversy on both sides, conservative and radical, during his preaching ministry at Shrewsbury. As early as 1620, just after Thomas Morton became Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, Herring was reported to the authorities for failure to use the prayer book and to receive or administer the sacraments. Morton had clashed with Puritan clergy in his former Diocese of Chester over ceremonial practices and the Declaration of Sports. His response had been eirenic Irenicism in Christian theology refers to attempts to unify Christian apologetical systems by using reason as an essential attribute. The word is derived from the Greek word ''ειρήνη (eirene)'' meaning peace. It is a concept related to a commu ...

in spirit, if sometimes exacting and abrasive in person: he had, for example, given Thomas Paget, a leading Lancashire Puritan minister, 10 shillings towards his legal expenses after compelling him to appear with a list of written arguments against signing with the cross in baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

. Morton referred Herring to two neighbouring ministers for satisfaction and he made a written statement of his reservations. The two ministers supported Herring with a certificate to the bishop and he pronounced himself satisfied with Herring's integrity. However, the incident opened up a series of suspensions and reinstatements.Clarke p. 465./ref> It seems that he continued to conduct private fasts and Bible expositions even during periods when his public ministry was made impossible. These would have been held in Draper's Hall, which was his own home.Coulton, p. 82. Opposition to Herring coalesced around Peter Studley, who was incumbent or

curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' (''cura'') ''of souls'' of a parish. In this sense, "curate" means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy w ...

of St Chad's from 1622 and also took responsibility for St Julian's, which was very close. His appointment seems to reflect the emergence on the corporation of a conservative opposition, which was able to appoint a second lecturer to St Alkmund's: Samuel Greaves, the Rector of Berrington, who preached on Wednesday mornings for £10 a year.Coulton, p. 83. An episcopal visitation of 1626, possibly attended by Morton himself, found Studley at loggerheads with the town's Puritans and many of the complaints and counter-claims were directly related to Herring's preaching ministry. The congregation of St Julian's were up in arms because, they alleged, Studley deliberately timed services to prevent them attending preaching elsewhere, but refrained from preaching himself. Studley reported Rowley and Wright for holding preaching and prayer meetings in their homes on Sunday evenings, suggesting that the episcopal court should judge whether or not these constituted conventicles. However, Studley was also meeting fierce opposition from a more radical group of poorer parishioners, of whom the most prominent were Katherine Chidley

Katherine Chidley (fl. 1616–1653) was an English Puritan activist and controversialist. Initially involved in resistance to episcopal authority and in separatist activity in Shrewsbury and London, she emerged during the English Civil War as a ...

and her family. Chidley had led a group of women in refusing to take part in the churching of women, which some Puritans found offensive and for which Studley demanded a fee. She arrived through her experiences at separatist conclusions and was later to write in justification of Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

or Congregationalist tendency within Puritanism. Herring was opposed to this group, and Clarke reports his frequent observation:

It is a sin of an high nature to unchurch a Nation at once, and that this would become the spring of many other fearful errours, for separation will eat like a Gangrene into the heart of Godlinesse. And he did pray, that they who would un-church others, might not be un-christianed themselves.Herring's opposition to separatism was also made manifest by his attendance at his local parish church, even though he had an appointment in a neighbouring parish. He attended the

Lord's Supper

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instituted ...

at St Mary's, a royal peculiar that was effectively controlled by the corporation. The vicar on Herring's arrival was William Bright, a nominee of the Puritan divine Laurence Chaderton

Laurence Chaderton (''c''. September 1536 – 13 November 1640) was an English Puritan divine, the first Master of Emmanuel College, Cambridge and one of the translators of the King James Version of the Bible.

Life

Chaderton was born in Lees, ...

, and congenial to Herring. However, Bright died in October 1618 and was buried on the 29th of that month. He was replaced, on Chaderton's recommendation, with Samuel Browne, a more moderate figure who nevertheless stoutly defended his church against episcopal interference. On 19 January 1620, the St Mary's parish register records the burial of "A sonn, being not baptized, of Mr. Hearing, a Mynester of God's word." Later in the same year, on 17 December, the register records a baptism: "Samuell, s. of Mr. Hearing, preacher of the Word." These descriptions suggest concord between Browne and Herring. Moreover, for the baptism of Dorcas on 30 January 1623 Herring is again described as a preacher of the Word, and for Mary's on 6 February 1625 as "Mynester," while Browne himself is described in the entry for his own daughter's baptism as "publique preacher." This suggests a looseness of terminology and a sense of equality and respect between the two clerics. The baptisms of two more children chart Herring's residence in the parish: for Joanna's on 19 August 1627 he is simply "Mr. Jolynus Hearing." However, after Browne's death in 1632 and the appointment of the Puritan James Betton to St Mary's, the entry for Herring's son Theophilus on 5 September 1633 again uses the title "Minister". As he continued a valued parishioner of St Mary's, Herring's position at St Alkmund's also became more secure. Heylyn operated through a group of Puritan ministers and businessmen who had established a body known as the Feoffees for Impropriations, sometimes known as the Collectors of St Antholin, to channel funds into Puritan preaching. Heylyn became a feoffee in 1626 and two years later oversaw the acquisition of the advowson

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living, ...

of St Alkmund's and a lease on the tithes of St Mary's. His distance from any radicalism strengthened his position, so that it was admitted even by his enemies:

Though he be scrupulous in matter of ceremony, yet he is a loyal subject unto the King, and a true friend unto the state.

Brampton Bryan

Brampton Bryan is a small village and civil parish situated in north Herefordshire, England close to the Shropshire and Welsh borders.

Brampton Bryan lies midway between Leintwardine and Knighton on the A4113 road. The nearest station is Buc ...

to preach in the town. It is possible that Samuel Clarke, Herring's biographer, also visited Shrewsbury. Along with John Ball, Pierson, Nicolls and Herring were part of a group who met for religious exercises in Sheriffhales at the home of Lady Margaret Bromley

Margaret Bromley ''née'' Lowe (died 1657) was a noted English Puritan of Staffordshire origins. She married Sir Edward Bromley, a noted lawyer and judge of the period. After his death she established a base for sheltering and supporting nonconf ...

,Clarke, p. 469./ref> widow from 1626 of the noted judge Sir Edward Bromley.

During the 1630s the bitterness of religious conflict at Shrewsbury intensified to a pitch that brought national attention and made Herring's position precarious. Bishop Wright's visitation of the town provided Studley with an opportunity for a triumphal reading of ordinances on the decoration of churches, but also for a denunciation of his opponents that revealed the depth of opposition. Herring's supporters, Rowley and Wright, were now joined by

During the 1630s the bitterness of religious conflict at Shrewsbury intensified to a pitch that brought national attention and made Herring's position precarious. Bishop Wright's visitation of the town provided Studley with an opportunity for a triumphal reading of ordinances on the decoration of churches, but also for a denunciation of his opponents that revealed the depth of opposition. Herring's supporters, Rowley and Wright, were now joined by Humphrey Mackworth

Sir Humphrey Mackworth (Jan 1657–1727) was a British Business magnate, industrialist and politician. He was involved in a business scandal in the early 18th century and was a founding member of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

...

as leaders of a group that refused to bow at the Name of Jesus and to kneel for communion, and so were counted as refusers of the Eucharist. Studley went on to write a savage denunciation of Puritanism, ''The Looking-Glass of Schisme'', claiming that religious nonconformity had influenced the commission of sensational murders at Clun

Clun ( cy, Colunwy) is a town in south west Shropshire, England, and the Shropshire Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The 2011 census recorded 680 people living in the town.Combined populations for the two output areas covering the tow ...

.Coulton, p. 86. The furore in Shrewsbury attracted the attention of William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

himself. Laud proposed to use negotiations over the renewal of the town's charter to prize the town's main churches free of the corporation's control. He acknowledged Herring's role in the town's opposition with the comment: "I will pickle up that Herring of Shrewsbury." Herring's response is reported as:

If he will abuse his power, let it teach Christians the more to use their prayers. And be then prayed that the Non-conformists enemies might by observation that they have a good God to trust unto, when trampled upon by ill-despised men.Laud instituted a visitation of the entire

Province of Canterbury

The Province of Canterbury, or less formally the Southern Province, is one of two ecclesiastical provinces which constitute the Church of England. The other is the Province of York (which consists of 12 dioceses).

Overview

The Province consist ...

in 1635, with Nathaniel Brent

Sir Nathaniel Brent (c. 1573 – 6 November 1652) was an English college head.

Life

He was the son of Anchor Brent of Little Wolford, Warwickshire, where he was born about 1573. He became 'portionist,' or postmaster, of Merton College, Oxford, i ...

conducting enquiries in the Lichfield diocese. Brent suspended Puritans at St Peter's Collegiate Church

St Peter's Collegiate Church is located in central Wolverhampton, England. For many centuries it was a chapel royal and from 1480 a royal peculiar, independent of the Diocese of Lichfield and even the Province of Canterbury. The collegiate chur ...

in Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton () is a city, metropolitan borough and administrative centre in the West Midlands, England. The population size has increased by 5.7%, from around 249,500 in 2011 to 263,700 in 2021. People from the city are called "Wulfrunian ...

, before moving on to Shrewsbury, where he also came into conflict with local clergy.Coulton, p. 88. At some point in the early part of 1635 Herring and his family left Shrewsbury.

Wrenbury

Herring sought a home first in Wrenbury,

Herring sought a home first in Wrenbury, Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county t ...

, where his wife's sister lived: Robert Nicolls, her husband and Herring's friend, had died at Sheriffhales in 1630. Wrenbury had originally been part of the parish of St Mary's Church, Acton

St Mary's Church is an active Anglican parish church located in Monk's Lane, Acton, a village to the west of Nantwich, Cheshire, England. Since 1967 it has been designated a Grade I listed building. A church has been present on this sit ...

, and its church was still in the gift of the vicar of Acton. The incumbent was William Peartree of Bury St Edmunds

Bury St Edmunds (), commonly referred to locally as Bury, is a historic market town, market, cathedral town and civil parish in Suffolk, England.OS Explorer map 211: Bury St.Edmunds and Stowmarket Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – ...

, who had been suspended by Brent. Herring had no formal appointment but lived privately as a parishioner, offering pastoral support by "comforting afflicted consciences." Clarke claimed that Herring only moved to Wrenbury after despairing of his future in Shrewsbury, but it seems that he had not taken steps formally to terminate his lectureship or even his tenancy. On 14 April 1635 the Drapers' Company resolved to write to Herring about rent arrears of £4 and to enquire whether he proposed to take up residence and preach before Midsummer, after which time they would let his house to "some brother of the company." It was duly leased on 17 September to John Betton, a draper.

Amsterdam

This was a time of indecision for Herring. He received invitations to leave for

This was a time of indecision for Herring. He received invitations to leave for New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

but felt it was not for him.Clake, p. 468./ref> His reservations may have been connected with a letter Herring and thirteen other Puritan clerics sent in 1637 to ministers in New England, which raised the alarm about separatism among them. However, towards the end of 1636, some friends put forward his name to John Rulice or Rulitius, then a pastorSteven, p. 279.

/ref> of the

English Reformed Church, Amsterdam

The English Reformed Church is one of the oldest buildings in Amsterdam, situated in the centre of the city. It is home to an English-speaking congregation which is affiliated to the Church of Scotland and to the Protestant Church in the Nethe ...

. Rulice had been sent to London to find someone who might take over the responsibilities of John Paget, the church's first pastor, now emeritus

''Emeritus'' (; female: ''emerita'') is an adjective used to designate a retired chair, professor, pastor, bishop, pope, director, president, prime minister, rabbi, emperor, or other person who has been "permitted to retain as an honorary title ...

. The opportunity faced Herring with numerous issues and conflicts. Not only was he concerned to be leaving family and friends: he had a vast library of records, that might incriminate them, but were of great personal and religious value to himself and his cause. After much deliberation, he burnt most of this collection, fearing a search of his person ''en route'' or of his home after he had left. This he described as that "Lesser martyrdom, wherein many of the best thoughts of his dearest friends were committed to flames." He was then forced to plan a secret journey, as Laud had forbidden clergy to travel abroad without a licence. After arranging a passage from Yarmouth

Yarmouth may refer to:

Places Canada

*Yarmouth County, Nova Scotia

**Yarmouth, Nova Scotia

**Municipality of the District of Yarmouth

**Yarmouth (provincial electoral district)

**Yarmouth (electoral district)

* Yarmouth Township, Ontario

*New ...

, he made a will on 24 August 1637, leaving bequests for his wife and eight children. He then visited his sisters and set off for the coast with a brother-in-law, Oliver Bowles of Sutton, Bedfordshire. He avoided interception, reaching Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Rotte'') is the second largest city and municipality in the Netherlands. It is in the province of South Holland, part of the North Sea mouth of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, via the ''"N ...

on 20 September and taking a wagon to Amsterdam the following day.Clarke, p. 470./ref> He moved in with a friend, Whittaker, pending the arrival of his family and his remaining property. Herring delivered his first sermon on : "The earth is the Lord's, and the fulness thereof; the world, and they that dwell therein." This met with great approval, securing his acceptance by the congregation. This paved the way for ratification by the Consistory of

Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former province on the western coast of the Netherlands. From the 10th to the 16th c ...

and the Classis of Amsterdam. From the outset, he took a full part in the liturgy and culture of the Dutch Reformed Church

The Dutch Reformed Church (, abbreviated NHK) was the largest Christian denomination in the Netherlands from the onset of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century until 1930. It was the original denomination of the Dutch Royal Family and ...

, keeping the fast decreed by the States General of the Netherlands

The States General of the Netherlands ( nl, Staten-Generaal ) is the supreme bicameral legislature of the Netherlands consisting of the Senate () and the House of Representatives (). Both chambers meet at the Binnenhof in The Hague.

The States ...

for the success of the army at the Siege of Breda. The arrival of his family the following day was a further relief, allowing him to commit himself to the post. He was joined after a couple of years by Thomas Paget, John's brother, who also took preaching and pastoral responsibilities at the English Reformed Church.

Amsterdam, then central to the wealth and culture of the Dutch Golden Age

The Dutch Golden Age ( nl, Gouden Eeuw ) was a period in the history of the Netherlands, roughly spanning the era from 1588 (the birth of the Dutch Republic) to 1672 (the Rampjaar, "Disaster Year"), in which Dutch trade, science, and Dutch art, ...

and a Protestant stronghold forged and tested in the Dutch Revolt

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) (Historiography of the Eighty Years' War#Name and periodisation, c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and t ...

and Thirty Years' war

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

, gave Herring at last an unrivalled platform. He was now part of a functioning presbyterian system, complete with a collegial ministry, much as he and moderate Puritans, like himself and the Pagets, had demanded for England. He was able to pronounce more or less freely on the situation at home, where Charles I's absolute monarchy ran into the crisis of the Bishops' War

The 1639 and 1640 Bishops' Wars () were the first of the conflicts known collectively as the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which took place in Scotland, England and Ireland. Others include the Irish Confederate Wars, the First and ...

, a prelude to the civil war in England. He prayed and spoke out for the establishment of a Presbyterian polity in England. He made a sharp distinction between the persons of the bishops, to whom he had no enmity, and their "Pride and Prelatical rule."Clarke, p. 471./ref> He continued to stress a middle position, troubled by the many fissile Independent and

Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

sects among the English exile community in the Netherlands. When one of his sons returned to England, presumably around 1643, he warned him not to take part in any subversion of Presbyterian polity, saying "I am sure it is the Government of Jesus Christ."

In 1640 he welcomed the invasion of northern England by a Scottish

In 1640 he welcomed the invasion of northern England by a Scottish Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from ''Covenan ...

army expressing the hope that the Scots "might be instruments of much good, but of no blood nor division between the two Nations." Clarke describes him as "one of God's special Remembrancers, in behalf of England, begging fervently that the Lords and Commons in Parliament, might be preserved from the two destructive rocks of pride and self-interest." In May 1642, Lloyd died, leaving a vacancy at St Alkmund's. The Puritan party in Shrewsbury, headed by Rowley and Mackworth, invited Herring back to resume his ministry but he probably declined. In the event, the corporation proved supine at the commencement of hostilities and a royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

''coup'' led by Francis Ottley

Sir Francis Ottley (1600/1601–11 September 1649) was an English Royalist politician and soldier who played an important part in the English Civil War in Shropshire. He was military governor of Shrewsbury during the early years of the war an ...

allowed the king's field army to occupy Shrewsbury on 20 September. The next stage of campaigning led to the major but indecisive Battle of Edgehill, which Herring greeted with the prayer:

Oh Lord wilt thou write Englands Reformation in red letters of her own blood; yet preserve thine own People, and maintaine thine own cause for Iesus Christs sake.

Death

Herring seems to have entered into a long illness and he was clearly troubled by periods of doubt as well as suffering, in the language of the time, assaults by Satan. His last reported words, after such a period of uncertainty, were: "He is overcome, overcome, through the strength of my Lord and only Saviour Iesus, unto whom I am now going to keep a Sabbath in glory." He died the following morning, given by Clarke as Sunday 28 March 1644. The date is widely but not universally accepted. William Steven in 1833 calculated Herring's ministry as lasting eight years from 1637, which implies he died in 1645. Coulton in 2010 noted that the corporation of Shrewsbury wrote to Herring again asking him to return, apparently in 1645, some months after the town fell to Parliamentarian forces. The corporation's invitation seems inconsistent with a death in 1644. Coulton is noncommital about the actual date, but points out that the register of the English Reformed Church shows he was certainly dead by 18 May 1645. The parishioners of Chad's parish in Shrewsbury subsequently switched their attention to Thomas Paget, Herring's co-pastor at Amsterdam, and in 1646 elected him their minister.Coulton, p. 106. Herring's will was proved by Christian, his widow on 26 March 1646.

Samuel Clarke's biography of Herring, part of a set of Puritan studies appended to his ''Generall Martyrologie'', appeared as early as 1651, under the

Herring seems to have entered into a long illness and he was clearly troubled by periods of doubt as well as suffering, in the language of the time, assaults by Satan. His last reported words, after such a period of uncertainty, were: "He is overcome, overcome, through the strength of my Lord and only Saviour Iesus, unto whom I am now going to keep a Sabbath in glory." He died the following morning, given by Clarke as Sunday 28 March 1644. The date is widely but not universally accepted. William Steven in 1833 calculated Herring's ministry as lasting eight years from 1637, which implies he died in 1645. Coulton in 2010 noted that the corporation of Shrewsbury wrote to Herring again asking him to return, apparently in 1645, some months after the town fell to Parliamentarian forces. The corporation's invitation seems inconsistent with a death in 1644. Coulton is noncommital about the actual date, but points out that the register of the English Reformed Church shows he was certainly dead by 18 May 1645. The parishioners of Chad's parish in Shrewsbury subsequently switched their attention to Thomas Paget, Herring's co-pastor at Amsterdam, and in 1646 elected him their minister.Coulton, p. 106. Herring's will was proved by Christian, his widow on 26 March 1646.

Samuel Clarke's biography of Herring, part of a set of Puritan studies appended to his ''Generall Martyrologie'', appeared as early as 1651, under the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execut ...

, and is informed by many who knew Herring.

Marriage and family

Herring married Christian Gellibrand during the time he was preaching at Calke. She was the third daughter of an English preacher who had served atVlissingen

Vlissingen (; zea, label=Zeelandic, Vlissienge), historically known in English as Flushing, is a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality and a city in the southwestern Netherlands on the former island of Walcheren. With its strategic l ...

, and a granddaughter of John Oxenbridge, a celebrated Warwickshire Puritan minister: hence she was a cousin of the John Oxenbridge

John Oxenbridge (30 January 1608 – 28 December 1674) was an English Nonconformist divine, who emigrated to New England.

Life

He was born at Daventry, Northamptonshire, and was educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and Magdalen Hall, Oxford ...

who was a notable minister at Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Massachusetts. Christian outlived her husband by some years and was still alive and evidently in good standing with the Reformed community in 1651, when Clarke published his biography. One of her sisters married Robert Nicolls, minister at Wrenbury, another married Oliver Bowles of Sutton, Bedfordshire, and a third married one Barry of Cottesmore, Rutland. These all formed part of the Puritan network which helped sustain Herring's ministry.

Julines and Christian Herring had 13 children, although some are known to have died and only eight are mentioned in Juline's will. A son, Jonathan, seems to have preceded the children born at Shrewsbury: it may have been he who reached the Netherlands with or earlier than his father, as Herring had a son with him before the rest of the family arrived. Clarke considered it a mark of enlightened and loving upbringing that, before disciplining his children, Herring explained to them the nature of any wrong they had done.

Mapping Julines Herring's life

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Footnotes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Herring, Julines 1582 births Year of death uncertain People from Montgomeryshire People educated at King Henry VIII School, Coventry Alumni of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge 17th-century English Puritan ministers English Jacobean nonconforming clergy 17th-century Calvinist and Reformed theologians Religion in Derbyshire Religion in Shropshire Religion in Cheshire Religion in Amsterdam Roundheads 17th century in Shropshire 17th century in Derbyshire 17th century in Cheshire