Julian Byng on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Byng was deployed in November 1899 to

Byng was deployed in November 1899 to  After three months serving as commander of the Cavalry Corps (United Kingdom), Cavalry Corps, beginning in May 1915, at which time he was also made a temporary Lieutenant-General (United Kingdom), lieutenant-general, Byng was off to Gallipoli to head the IX Corps (United Kingdom), IX Corps and supervise the successful British, Australian, and New Zealand forces withdrawal from the ill-fated campaign. For this, he was on 1 January 1916 elevated within the Order of the Bath to the rank of Knight Commander, but was not allowed much rest, as he spent the next month commanding the Suez Canal defences before returning to the Western Front (World War I), Western Front to lead the XVII Corps (United Kingdom), XVII Corps. By June, he was in command of the

After three months serving as commander of the Cavalry Corps (United Kingdom), Cavalry Corps, beginning in May 1915, at which time he was also made a temporary Lieutenant-General (United Kingdom), lieutenant-general, Byng was off to Gallipoli to head the IX Corps (United Kingdom), IX Corps and supervise the successful British, Australian, and New Zealand forces withdrawal from the ill-fated campaign. For this, he was on 1 January 1916 elevated within the Order of the Bath to the rank of Knight Commander, but was not allowed much rest, as he spent the next month commanding the Suez Canal defences before returning to the Western Front (World War I), Western Front to lead the XVII Corps (United Kingdom), XVII Corps. By June, he was in command of the  As a result of the success at Cambrai, Byng was made Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in the 1919 New Year's Honours. In the United States, Byng's exploits during the First World War were commemorated near the town of Ada, Oklahoma, when in 1917 a post office and power plant were named after him, leading to the later emergence of the town of Byng, Oklahoma, Byng. Further, Byng was in his own right elevated on 7 October 1919 to the peerage as Baron Byng of Vimy, of Thorpe-le-Soken in the County of Essex. The next month, though he was offered the Southern Command (United Kingdom), Southern Command, Byng retired from the military and moved to Thorpe Hall. In April 1921, he unveiled the Chipping Barnet War Memorial, near to his family seat of Wrotham Park.

As a result of the success at Cambrai, Byng was made Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in the 1919 New Year's Honours. In the United States, Byng's exploits during the First World War were commemorated near the town of Ada, Oklahoma, when in 1917 a post office and power plant were named after him, leading to the later emergence of the town of Byng, Oklahoma, Byng. Further, Byng was in his own right elevated on 7 October 1919 to the peerage as Baron Byng of Vimy, of Thorpe-le-Soken in the County of Essex. The next month, though he was offered the Southern Command (United Kingdom), Southern Command, Byng retired from the military and moved to Thorpe Hall. In April 1921, he unveiled the Chipping Barnet War Memorial, near to his family seat of Wrotham Park.

The Governor General travelled the length and breadth of the country, meeting with Canadians wherever he went. He also immersed himself in Canada's culture and came to particularly love Ice hockey, hockey, rarely missing a game played by the Ottawa Senators (original), Ottawa Senators. He was also fond of the Royal Agricultural Winter Fair, held each year in Toronto, and established the Governor General's Cup to be presented at the competition. He was the first Governor General of Canada to appoint Canadians as his Aide-de-Camp, aides-de-camp (one of whom was future Governor General Georges Vanier) and approached his viceregal role with enthusiasm, gaining popularity with Canadians on top of that received from the men he had commanded on the European battlefields.

The Governor General travelled the length and breadth of the country, meeting with Canadians wherever he went. He also immersed himself in Canada's culture and came to particularly love Ice hockey, hockey, rarely missing a game played by the Ottawa Senators (original), Ottawa Senators. He was also fond of the Royal Agricultural Winter Fair, held each year in Toronto, and established the Governor General's Cup to be presented at the competition. He was the first Governor General of Canada to appoint Canadians as his Aide-de-Camp, aides-de-camp (one of whom was future Governor General Georges Vanier) and approached his viceregal role with enthusiasm, gaining popularity with Canadians on top of that received from the men he had commanded on the European battlefields.

1884: Khedive's Star

* 12 September 1916: Order of St. Vladimir, Order of St Vladimir, 4th Class (with Swords)

* 8 March 1918: ''Croix de guerre (Belgium), Croix de guerre''

* 29 January 1919 – 6 June 1935: ''Legion of Honour, Grand officier de Légion d'honneur''

* 11 March 1919: ''Croix de guerre 1914–1918 (France), Croix de guerre''

* 12 July 1919: Distinguished Service Medal (U.S. Army), Distinguished Service Medal

* 24 October 1919 – 6 June 1935: Order of the White Eagle (Serbia), Grand Cross With Swords of the Order of the White Eagle

1884: Khedive's Star

* 12 September 1916: Order of St. Vladimir, Order of St Vladimir, 4th Class (with Swords)

* 8 March 1918: ''Croix de guerre (Belgium), Croix de guerre''

* 29 January 1919 – 6 June 1935: ''Legion of Honour, Grand officier de Légion d'honneur''

* 11 March 1919: ''Croix de guerre 1914–1918 (France), Croix de guerre''

* 12 July 1919: Distinguished Service Medal (U.S. Army), Distinguished Service Medal

* 24 October 1919 – 6 June 1935: Order of the White Eagle (Serbia), Grand Cross With Swords of the Order of the White Eagle

Website of the Governor General of Canada entry for Julian Byng

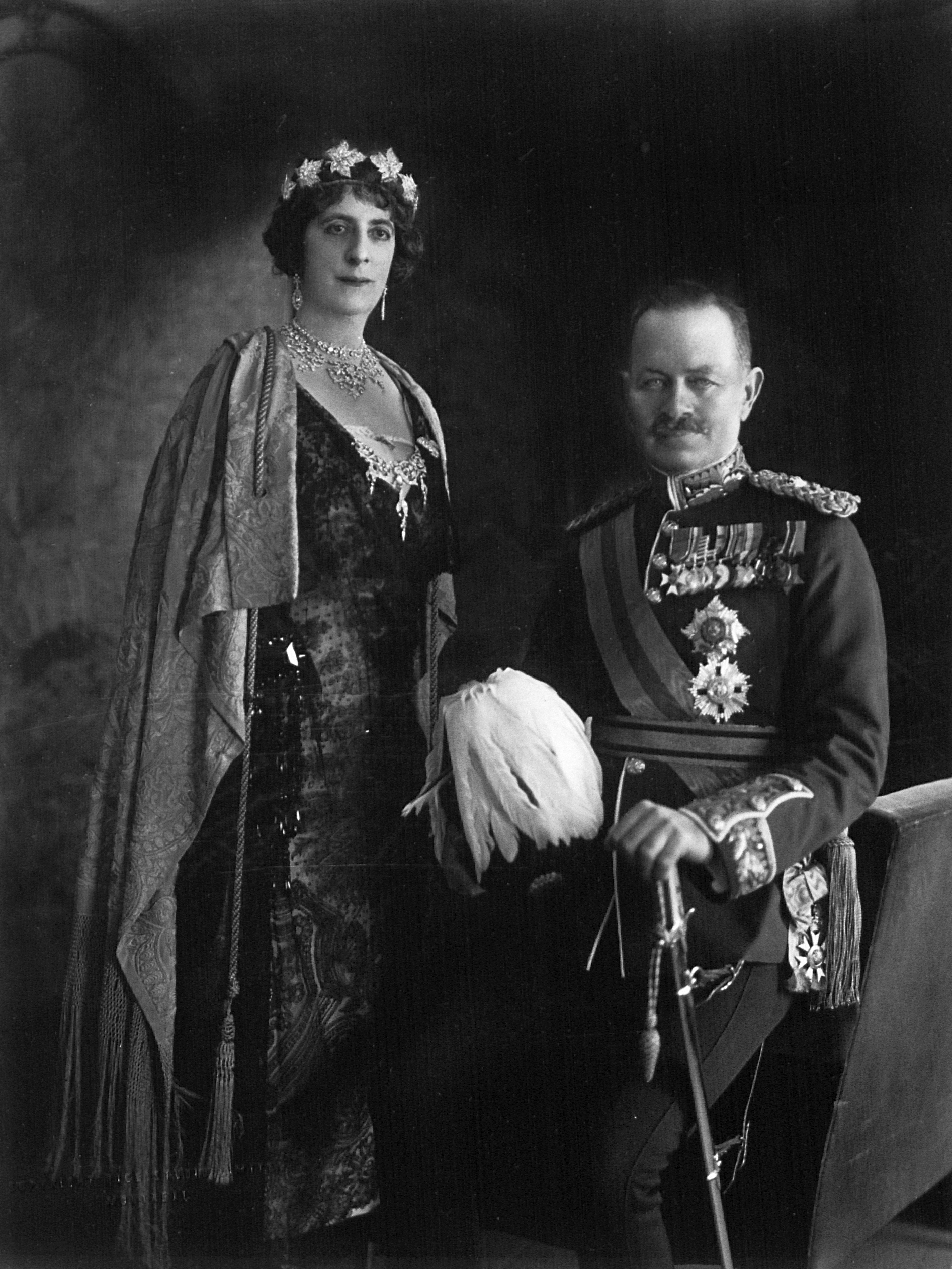

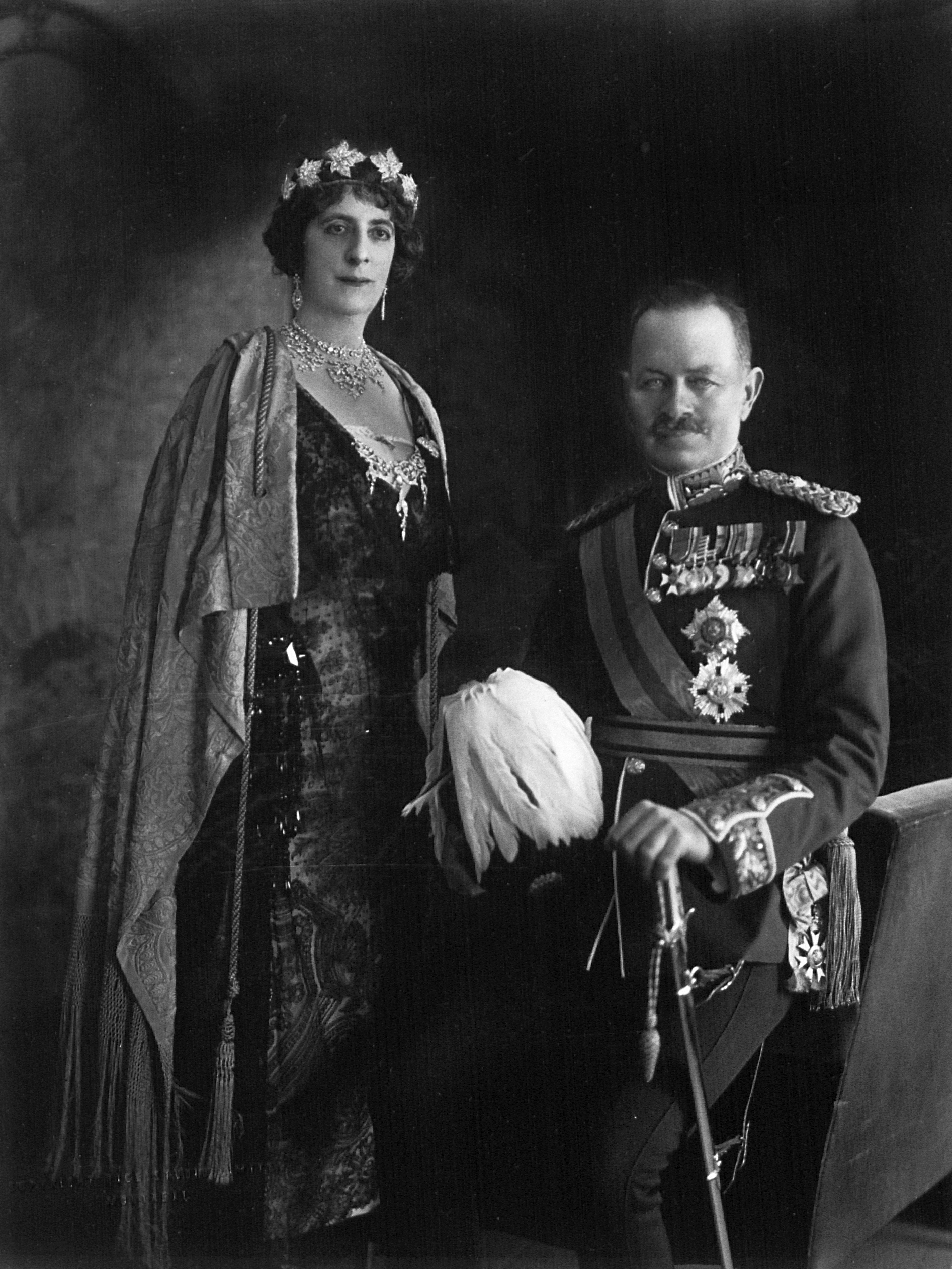

Portraits of Byng in the National Portrait Gallery

, - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Byng of Vimy, Julian H. G. Byng, 1st Viscount Governors General of Canada Commissioners of Police of the Metropolis People educated at Eton College British field marshals British Army personnel of the Mahdist War British Army cavalry generals of World War I Grand Officiers of the Légion d'honneur Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Members of the Royal Victorian Order Foreign recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States) Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) Royal Military College of Canada people Scouting and Guiding in Canada Viscounts in the Peerage of the United Kingdom Younger sons of earls 1862 births 1935 deaths People from Chipping Barnet 10th Royal Hussars officers King's Royal Rifle Corps officers British Militia officers South African Light Horse officers British Army personnel of the Second Boer War Chief Scouts of Canada Byng family, Julian People from Thorpe-le-Soken Graduates of the Staff College, Camberley Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Viscounts created by George V Military personnel from Hertfordshire Burials in Essex

Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

Julian Hedworth George Byng, 1st Viscount Byng of Vimy, (11 September 1862 – 6 June 1935) was a British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

officer who served as Governor General of Canada

The governor general of Canada (french: gouverneure générale du Canada) is the federal viceregal representative of the . The is head of state of Canada and the 14 other Commonwealth realms, but resides in oldest and most populous realm, t ...

, the 12th

12 (twelve) is the natural number following 11 and preceding 13. Twelve is a superior highly composite number, divisible by 2, 3, 4, and 6.

It is the number of years required for an orbital period of Jupiter. It is central to many systems ...

since the Canadian Confederation

Canadian Confederation (french: Confédération canadienne, link=no) was the process by which three British North American provinces, the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, were united into one federation called the Canada, Dom ...

.

Known to friends as "Bungo", Byng was born to a noble

A noble is a member of the nobility.

Noble may also refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Noble Glacier, King George Island

* Noble Nunatak, Marie Byrd Land

* Noble Peak, Wiencke Island

* Noble Rocks, Graham Land

Australia

* Noble Island, Great B ...

family at Wrotham Park

Wrotham Park (pronounced , ) is a neo-Palladian English country house in the parish of South Mimms, Hertfordshire. It lies south of the town of Potters Bar, from Hyde Park Corner in central London. The house was designed by Isaac Ware in 1754 ...

in Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

, England and educated at Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

, along with his brothers. Upon graduation, he received a commission as a militia officer and saw service in Egypt and Sudan before enrolling in the Staff College at Camberley. There, he befriended individuals who would be his contemporaries when he attained senior rank in France. Following distinguished service during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

—specifically, with the British Expeditionary Force in France, in the Battle of Gallipoli, as commander of the Canadian Corps

The Canadian Corps was a World War I corps formed from the Canadian Expeditionary Force in September 1915 after the arrival of the 2nd Canadian Division in France. The corps was expanded by the addition of the 3rd Canadian Division in December ...

at Vimy Ridge

The Battle of Vimy Ridge was part of the Battle of Arras, in the Pas-de-Calais department of France, during the First World War. The main combatants were the four divisions of the Canadian Corps in the First Army, against three divisions of ...

, and as commander of the British Third Army—Byng was elevated to the peerage in 1919. In 1921, King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

, on the recommendation of Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

, appointed him to replace the Duke of Devonshire

Duke of Devonshire is a title in the Peerage of England held by members of the Cavendish family. This (now the senior) branch of the Cavendish family has been one of the wealthiest British aristocratic families since the 16th century and has b ...

as Canada's governor general, a post he occupied until the Viscount Willingdon succeeded him in 1926. Byng proved to be popular with Canadians due to his war leadership, though his stepping directly into political affairs became the catalyst for widespread changes to the role of the Crown in all of the British Dominions.

After his viceregal tenure, Byng returned to the UK to be appointed Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis

The Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis is the head of London's Metropolitan Police Service. Sir Mark Rowley was appointed to the post on 8 July 2022 after Dame Cressida Dick announced her resignation in February.

The rank of Commissione ...

and was promoted within the peerage to become Viscount Byng of Vimy. Three years after attaining the rank of field marshal, he died at his home, Thorpe Hall on 6 June 1935.

Early life

Byng was born at the family seat ofWrotham Park

Wrotham Park (pronounced , ) is a neo-Palladian English country house in the parish of South Mimms, Hertfordshire. It lies south of the town of Potters Bar, from Hyde Park Corner in central London. The house was designed by Isaac Ware in 1754 ...

, in Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

, as the seventh son and 13th and youngest child of George Byng, 2nd Earl of Strafford

George Stevens Byng, 2nd Earl of Strafford, PC (8 June 1806 – 29 October 1886), styled Viscount Enfield between 1847 and 1860, of Wrotham Park in Middlesex (now Hertfordshire) and of 5 St James's Square, London, was a British peer and Whig p ...

(who, due to the size of his family, ran a relatively frugal household) and Harriet Elizabeth Cavendish, daughter of Charles Cavendish, 1st Baron Chesham

Charles Compton Cavendish, 1st Baron Chesham (28 August 1793 – 12 November 1863) was a British Liberal politician.

Early life

Cavendish was the fourth son of George Augustus Henry Cavendish, 1st Earl of Burlington, third son of the former Pri ...

. Until the age of 17, Byng was enrolled at Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

, although he did not enter the sixth form

In the education systems of England, Northern Ireland, Wales, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and some other Commonwealth countries, sixth form represents the final two years of secondary education, ages 16 to 18. Pupils typically prepare for A-l ...

. At Eton Byng first received the nickname "Bungo"—to distinguish him from his elder brothers "Byngo" and "Bango"—but his time at the college was undistinguished, and he received poor reports; indicative of his attitude towards academics, he once traded his Latin grammar book and his brother Lionel's best trousers to a hawker

Hawker or Hawkers may refer to:

Places

* Hawker, Australian Capital Territory, a suburb of Canberra

* Hawker, South Australia, a town

* Division of Hawker, an Electoral Division in South Australia

* Hawker Island, Princess Elizabeth Land, Antarct ...

for a pair of ferret

The ferret (''Mustela furo'') is a small, Domestication, domesticated species belonging to the family Mustelidae. The ferret is most likely a domesticated form of the wild European polecat (''Mustela putorius''), evidenced by their Hybrid (biol ...

s and a pineapple

The pineapple (''Ananas comosus'') is a tropical plant with an edible fruit; it is the most economically significant plant in the family Bromeliaceae. The pineapple is indigenous to South America, where it has been cultivated for many centuri ...

. Byng later claimed that he had been the school's worst "Scug", the colloquial term for an undistinguished boy.

Military career

Byng was from a military family, hisgrandfather

Grandparents, individually known as grandmother and grandfather, are the parents of a person's father or mother – paternal or maternal. Every sexually-reproducing living organism who is not a genetic chimera has a maximum of four genetic ...

having served with Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

at the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

. With three brothers already in the army and another already put up for the 7th Queen's Own Hussars

The 7th Queen's Own Hussars was a cavalry regiment in the British Army, first formed in 1689. It saw service for three centuries, including the First World War and the Second World War. The regiment survived the immediate post-war reduction in ...

, Byng's father did not think he could afford a regular army commission for his youngest son. Thus, at the age of 17, Byng was instead sent into the militia and on 12 December 1879 commissioned as a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

into the 2nd (Edmonton) Royal Middlesex Rifles (later known as 7th Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps

The King's Royal Rifle Corps was an infantry rifle regiment of the British Army that was originally raised in British North America as the Royal American Regiment during the phase of the Seven Years' War in North America known in the United St ...

). He was promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

on 23 April 1881. During this period, Byng also developed a liking for theatre and music hall

Music hall is a type of British theatrical entertainment that was popular from the early Victorian era, beginning around 1850. It faded away after 1918 as the halls rebranded their entertainment as variety. Perceptions of a distinction in Bri ...

s, and by the age of twenty had taken an interest in the banjo

The banjo is a stringed instrument with a thin membrane stretched over a frame or cavity to form a resonator. The membrane is typically circular, and usually made of plastic, or occasionally animal skin. Early forms of the instrument were fashi ...

.

At a meeting of the Jockey Club

The Jockey Club is the largest commercial horse racing organisation in the United Kingdom. It owns 15 of Britain's famous racecourses, including Aintree, Cheltenham, Epsom Downs and both the Rowley Mile and July Course in Newmarket, amo ...

in 1882, Byng's father was asked about his sons by his long-time friend, Albert Edward, Prince of Wales

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria and ...

. Upon hearing that Byng had not yet found a permanent career, the Prince offered a place for him in his own regiment, the 10th Royal Hussars

The 10th Royal Hussars (Prince of Wales's Own) was a cavalry regiment of the British Army raised in 1715. It saw service for three centuries including the First World War and Second World War but then amalgamated with the 11th Hussars (Prince A ...

. This was the most expensive regiment in the army, and the Earl of Strafford could only afford to give Byng two hundred of the six hundred pounds he would need each year, but the Prince's offer could not be refused. Byng himself was delighted at the opportunity, as both his uncle, Lord Chesham

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or a ...

, and his cousin, Charles Cavendish, had served in the regiment. By raising money through buying polo ponies cheaply, using his excellent horsemanship to train them, and then selling them on at a profit, Byng was able to transfer to the 10th Royal Hussars on 27 January 1883, and less than three months later he joined the regiment in Lucknow

Lucknow (, ) is the capital and the largest city of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and it is also the second largest urban agglomeration in Uttar Pradesh. Lucknow is the administrative headquarters of the eponymous district and division ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

.

It was while the regiment was on the way home to Great Britain in 1884 that the Hussars were diverted to the Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

to join the Suakin Expedition

The Suakin Expedition was either of two British military expeditions, led by Major-General Sir Gerald Graham V.C., to Suakin in Sudan, with the intention of destroying the power of the Sudanese military commander Osman Digna and his troops during ...

, and on 29 February Byng, along with the rest of his regiment, rode in the first line of the charge at the first Battle of El Teb

The First and Second Battles of El Teb (4 February 1884 and 29 February 1884) took place during the British Sudan Campaign where a force of Sudanese under Osman Digna won a victory over a 3,500 strong Egyptian force under the command of Gener ...

. The attack, which resulted in the deaths of both of Byng's squadron's other officers, was unsuccessful, and fighting continued, with Byng's horse being killed under him on 13 March at the Battle of Tamai

The Battle of Tamai (or Tamanieh) took place on 13 March 1884 between a British force under Sir Gerald Graham and a Mahdist Sudanese army led by Osman Digna.

Despite his earlier victory at El Teb, Graham realised that Osman Digna's force was fa ...

. Most of the rebels were then dispersed shortly after, and on 29 March the regiment re-embarked for Britain, arriving on 22 April, and proceeding to their new base at Shorncliffe Army Camp

Shorncliffe Army Camp is a large military camp near Cheriton in Kent. Established in 1794, it later served as a staging post for troops destined for the Western Front during the First World War.

History

The camp was established in 1794 when t ...

in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. During the summer of 1884, Byng spent much of his time playing polo

Polo is a ball game played on horseback, a traditional field sport and one of the world's oldest known team sports. The game is played by two opposing teams with the objective of scoring using a long-handled wooden mallet to hit a small hard ...

and training recruits and horses, and in July, for his services in Sudan, he was mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches, MiD) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face ...

.

In June 1885, the regiment was relocated to the South Cavalry Barracks at Aldershot

Aldershot () is a town in Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme northeast corner of the county, southwest of London. The area is administered by Rushmoor Borough Council. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Alders ...

, where the Prince of Wales' eldest son, Prince Albert Victor

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale (Albert Victor Christian Edward; 8 January 1864 – 14 January 1892) was the eldest child of the Prince and Princess of Wales (later King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra) and grandson of the re ...

, joined the regiment and thereafter the Prince of Wales and his other son, Prince George, became frequent visitors. Byng struck up a friendship with both Albert Victor and George, but did not socialise with them much outside of army circles. Byng was appointed as the regimental adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of human resources in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed forces as a non-commission ...

on 20 October 1886, only nine days before the death of his father, who left Byng a watch and £3,500. The regiment then moved again in 1887 to the barracks at Hounslow

Hounslow () is a large suburban district of West London, west-southwest of Charing Cross. It is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Hounslow, and is identified in the London Plan as one of the 12 metropolitan centres in Gr ...

, where, after suspecting that contractors were selling him inferior meat, Byng spent several early mornings at the Smithfield market

Smithfield, properly known as West Smithfield, is a district located in Central London, part of Farringdon Without, the most westerly ward of the City of London, England.

Smithfield is home to a number of City institutions, such as St Bartho ...

to learn the meat trade, eventually proving his case and having the contractors changed. It was also at this time that Byng became acquainted with the Lord Rowton, who, along with the Guinness Trust

The Guinness Partnership is one of the largest providers of affordable housing and care in England. Founded as a charitable trust in 1890, it is now a Community Benefit Society with eight members. Bloomberg classify it as a real estate owner an ...

, was trying to improve housing for skilled workers in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

. Byng accompanied Rowton around the poorest areas of the city and suggested that retired senior soldiers from the rank-and-file be hired to maintain order in the Rowton Houses

Rowton Houses was a chain of hostels built in London, England, by the Victorian philanthropist Lord Rowton to provide decent accommodation for working men in place of the squalid lodging houses of the time.

George Orwell, in his 1933 book ''D ...

that Rowton had set up, thus starting a long-lived tradition.

Staff College

In 1888, the Hussars again moved, this time toYork

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, where Byng kept his men busy by raising successful cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

and football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

teams. Byng was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on 4 January 1890, around the time he began to consider entering the Staff College at Camberley. He thus, in order to dedicate his time to preparatory studies, which continued when the regiment moved in 1891 to Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, resigned his commission as adjutant and turned down an invitation from Prince Albert Victor to join him in India as an equerry

An equerry (; from French ' stable', and related to 'squire') is an officer of honour. Historically, it was a senior attendant with responsibilities for the horses of a person of rank. In contemporary use, it is a personal attendant, usually up ...

. After being detached for a time in order to serve and gain more experience in the infantry and artillery, Byng sat and passed his entrance exams into the Staff College and secured a nomination in September 1892. A year before Byng entered the college, Albert Victor fell victim to the influenza pandemic

An influenza pandemic is an epidemic of an influenza virus that spreads across a large region (either multiple continents or worldwide) and infects a large proportion of the population. There have been six major influenza epidemics in the last ...

that raged around the world, and, at the Prince's funeral on 20 January 1892, Byng commanded the pallbearer

A pallbearer is one of several participants who help carry the casket at a funeral. They may wear white gloves in order to prevent damaging the casket and to show respect to the deceased person.

Some traditions distinguish between the roles of ...

s (all from the 10th Royal Hussars), which was a significant display of trust shown Byng by the Prince of Wales.

Once Byng was enrolled at the Staff College, he found amongst his fellow students men with whom he would be closely associated more than two decades later— Henry Rawlinson, Henry Hughes Wilson

Field Marshal Sir Henry Hughes Wilson, 1st Baronet, (5 May 1864 – 22 June 1922) was one of the most senior British Army staff officers of the First World War and was briefly an Irish unionist politician.

Wilson served as Commandant of the ...

, Thomas D'Oyly Snow, and James Aylmer Lowthorpe Haldane

General Sir James Aylmer Lowthorpe Haldane, (17 November 1862 – 19 April 1950) was a Scottish soldier who rose to high rank in the British Army.

Early life

Born to physician Daniel Rutherford Haldane and his wife Charlotte Elizabeth née Lo ...

—and in 1894, while en route to visit a friend at Aldershot, travelled with a cadet at the nearby Royal Military College, Sandhurst

The Royal Military College (RMC), founded in 1801 and established in 1802 at Great Marlow and High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire, England, but moved in October 1812 to Sandhurst, Berkshire, was a British Army military academy for training infantry a ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

. Byng also journeyed with his class to see the battlefields of the Franco-Prussian War at Alsace-Lorraine and accompanied to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

one of his lecturers who was compiling information on a book on Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

. By December 1894, Byng graduated from the Staff College and was immediately appointed to command the A Squadron

Squadron may refer to:

* Squadron (army), a military unit of cavalry, tanks, or equivalent subdivided into troops or tank companies

* Squadron (aviation), a military unit that consists of three or four flights with a total of 12 to 24 aircraft, de ...

of the hussars. Only three years later, though, the regiment returned to Aldershot and Byng left to become adjutant of the 1st Cavalry Brigade, shortly before becoming the Deputy Assistant Adjutant-General (DAAG) of the Aldershot Command

Aldershot () is a town in Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme northeast corner of the county, southwest of London. The area is administered by Rushmoor Borough Council. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Alders ...

, and was promoted to the rank of major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

on 4 May 1898. Later that same year, Byng met at a local party Marie Evelyn Moreton

Evelyn Byng, Viscountess Byng of Vimy ( Marie Evelyn Moreton; 11 January 1870 – 20 June 1949), also known as Lady Byng, was the wife of Lord Byng, the 12th Governor General of Canada (1921–26).

Biography

Born as Marie Evelyn Moreton ...

, the only daughter of Sir Richard Charles Moreton, who had himself served as comptroller

A comptroller (pronounced either the same as ''controller'' or as ) is a management-level position responsible for supervising the quality of accounting and financial reporting of an organization. A financial comptroller is a senior-level executi ...

at the Canadian royal and viceroyal residence of Rideau Hall

Rideau Hall (officially Government House) is the official residence in Ottawa of both the Canadian monarch and their representative, the governor general of Canada. It stands in Canada's capital on a estate at 1 Sussex Drive, with the main b ...

, under the then Governor General of Canada

The governor general of Canada (french: gouverneure générale du Canada) is the federal viceregal representative of the . The is head of state of Canada and the 14 other Commonwealth realms, but resides in oldest and most populous realm, t ...

the Marquess of Lorne. Evelyn, as she was known, later described her early encounters with Byng:

Commanding officer and First World War

Byng was deployed in November 1899 to

Byng was deployed in November 1899 to South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

, where he was to act as a provost marshal

Provost marshal is a title given to a person in charge of a group of Military Police (MP). The title originated with an older term for MPs, '' provosts'', from the Old French ''prévost'' (Modern French ''prévôt''). While a provost marshal i ...

, but was instead immediately given the local rank of lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

and tasked with raising and commanding the South African Light Horse

The South African Light Horse regiment of the British Army were raised in Cape Colony in 1899 and disbanded in 1907.

The commanding officer tasked with raising the regiment was Major (locally a Lieutenant Colonel) the Honourable Julian Byng. ( ...

during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

. Byng thereafter served on the front lines, during which time he ended up in command of a group of columns, was mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches, MiD) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face ...

five times (including by Lord Kitchener on 23 June 1902), and in November 1900 was promoted to brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

lieutenant colonel and in February 1902 to brevet colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

. The beginning of 1902 brought more significant events for Byng, with his return to England in March, an audience with King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria an ...

the following month, at which he was appointed to the Royal Victorian Order

The Royal Victorian Order (french: Ordre royal de Victoria) is a dynastic order of knighthood established in 1896 by Queen Victoria. It recognises distinguished personal service to the British monarch, Canadian monarch, Australian monarch, o ...

as a member 4th class (MVO), and his marriage to Evelyn Moreton at St Paul's Church, Knightsbridge

St Paul's Church, Knightsbridge, is a Grade II*listed Anglican church of the Anglo-Catholic tradition located at 32a Wilton Place in Knightsbridge, London.

History and architecture

The church was founded in 1843, the first in London to champion ...

, on 30 April 1902. Following a second visit to the King in early October, Byng was sent back to India to command the 10th Royal Hussars at Mhow

Mhow, officially Dr. Ambedkar Nagar, is a town in the Indore district in Madhya Pradesh state of India. It is located south-west of Indore city, towards Mumbai on the old Mumbai-Agra Road. The town was renamed as ''Dr. Ambedkar Nagar'' in 20 ...

and was appointed to the rank of a substantive lieutenant colonel on 11 October 1902.

In his first two years of marriage, Byng's wife suffered several miscarriage

Miscarriage, also known in medical terms as a spontaneous abortion and pregnancy loss, is the death of an embryo or fetus before it is able to survive independently. Miscarriage before 6 weeks of gestation is defined by ESHRE as biochemical lo ...

s, resulting in the declaration that she would be unable to bear children. By January 1904, Byng had also, while playing polo, broken his right elbow so severely that it was feared he would have to quit the Army. After four months' treatment in England, though, he was pronounced to be again fit for duty and in May became the first commandant of the new cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

school at Netheravon

Netheravon is a village and civil parish on the River Avon and A345 road, about north of the town of Amesbury in Wiltshire, South West England. It is within Salisbury Plain.

The village is on the right (west) bank of the Avon, opposite Fit ...

. The posting was to be only a brief one, as, on 11 May 1905, Byng was made commander of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade at Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour.

...

, with the simultaneous temporary rank of brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

and substantive rank of colonel. After appointment as a Companion of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved Bathing#Medieval ...

(CB) in 1906, he was again back in Aldershot, in command of the 1st Cavalry Brigade.

It was April 1909 when Byng was promoted to major-general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

and, though he was placed on half pay, Byng—with added income from editing the ''Cavalry Journal'' and serving as the first north Essex District Commissioner for the Boy Scouts

Boy Scouts may refer to:

* Boy Scout, a participant in the Boy Scout Movement.

* Scouting, also known as the Boy Scout Movement.

* An organisation in the Scouting Movement, although many of these organizations also have female members. There are ...

—purchased his first house, Newton Hall, in Dunmow, Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

. He would, however, only reside there for two years, as, exactly the same amount of time after taking command of the East Anglian Infantry Division of the Territorial Force

The Territorial Force was a part-time volunteer component of the British Army, created in 1908 to augment British land forces without resorting to conscription. The new organisation consolidated the 19th-century Volunteer Force and yeomanry i ...

in October 1910, Byng became General Officer Commanding the British Troops in Egypt, where he remained until the outbreak of the World War I, First World War. He then returned briefly to the United Kingdom to take leadership of the 3rd Cavalry Division (United Kingdom), 3rd Cavalry Division before going with the British Expeditionary Force to France and the First Battle of Ypres. His actions there were rewarded in March 1915 with appointment as a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George, Order of St. Michael and St. George.

After three months serving as commander of the Cavalry Corps (United Kingdom), Cavalry Corps, beginning in May 1915, at which time he was also made a temporary Lieutenant-General (United Kingdom), lieutenant-general, Byng was off to Gallipoli to head the IX Corps (United Kingdom), IX Corps and supervise the successful British, Australian, and New Zealand forces withdrawal from the ill-fated campaign. For this, he was on 1 January 1916 elevated within the Order of the Bath to the rank of Knight Commander, but was not allowed much rest, as he spent the next month commanding the Suez Canal defences before returning to the Western Front (World War I), Western Front to lead the XVII Corps (United Kingdom), XVII Corps. By June, he was in command of the

After three months serving as commander of the Cavalry Corps (United Kingdom), Cavalry Corps, beginning in May 1915, at which time he was also made a temporary Lieutenant-General (United Kingdom), lieutenant-general, Byng was off to Gallipoli to head the IX Corps (United Kingdom), IX Corps and supervise the successful British, Australian, and New Zealand forces withdrawal from the ill-fated campaign. For this, he was on 1 January 1916 elevated within the Order of the Bath to the rank of Knight Commander, but was not allowed much rest, as he spent the next month commanding the Suez Canal defences before returning to the Western Front (World War I), Western Front to lead the XVII Corps (United Kingdom), XVII Corps. By June, he was in command of the Canadian Corps

The Canadian Corps was a World War I corps formed from the Canadian Expeditionary Force in September 1915 after the arrival of the 2nd Canadian Division in France. The corps was expanded by the addition of the 3rd Canadian Division in December ...

and was promoted when, for distinguished service, the King made substantive Byng's rank of lieutenant-general. Byng's greatest glory then came when he led the Canadian victory in April 1917 at the Battle of Vimy Ridge, a historic military milestone for the Dominion that inspired nationalism at home.

In June 1917, and holding the temporary rank of General (United Kingdom), general, Byng took command of Britain's largest army, the Third Army (United Kingdom), Third Army, until the cessation of hostilities and, with those troops, at the First Battle of Cambrai (1917), Battle of Cambrai, conducted the first surprise attack using tanks. The Battle of Cambrai was later considered a turning point in the war and Byng was honoured on 24 November 1917 by having his temporary rank of general made substantive; however according to the World War I memoir of A S Bullock, the First Battle of Cambrai failed to breach the Hindenburg Line, due to lack of reserves, and it was at General Byng's second attempt to take Cambrai in 1918 that the British triumphed, owing to sufficient troops and supplies being in place 'to sustain the attack day and night until the Germans were broken'.

As a result of the success at Cambrai, Byng was made Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in the 1919 New Year's Honours. In the United States, Byng's exploits during the First World War were commemorated near the town of Ada, Oklahoma, when in 1917 a post office and power plant were named after him, leading to the later emergence of the town of Byng, Oklahoma, Byng. Further, Byng was in his own right elevated on 7 October 1919 to the peerage as Baron Byng of Vimy, of Thorpe-le-Soken in the County of Essex. The next month, though he was offered the Southern Command (United Kingdom), Southern Command, Byng retired from the military and moved to Thorpe Hall. In April 1921, he unveiled the Chipping Barnet War Memorial, near to his family seat of Wrotham Park.

As a result of the success at Cambrai, Byng was made Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in the 1919 New Year's Honours. In the United States, Byng's exploits during the First World War were commemorated near the town of Ada, Oklahoma, when in 1917 a post office and power plant were named after him, leading to the later emergence of the town of Byng, Oklahoma, Byng. Further, Byng was in his own right elevated on 7 October 1919 to the peerage as Baron Byng of Vimy, of Thorpe-le-Soken in the County of Essex. The next month, though he was offered the Southern Command (United Kingdom), Southern Command, Byng retired from the military and moved to Thorpe Hall. In April 1921, he unveiled the Chipping Barnet War Memorial, near to his family seat of Wrotham Park.

Governor General of Canada

After Byng was made in July 1921 a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Michael and St. George, it was announced on 2 August that KingGeorge V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

had, by commission under the royal sign-manual and Seal (device)#Signet rings, signet, approved the recommendation of his Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, British prime minister, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

, to appoint Byng as his representative in Canada. The designation proved less controversial than his predecessor, the Duke of Devonshire

Duke of Devonshire is a title in the Peerage of England held by members of the Cavendish family. This (now the senior) branch of the Cavendish family has been one of the wealthiest British aristocratic families since the 16th century and has b ...

, due partly to the General's popularity, but also because the practice of prior consultation with the Prime Minister of Canada, Canadian prime minister, at that time Arthur Meighen, was revived. Byng had not been Meighen's first choice for presentation to the King, since he preferred someone with more civilian credentials. Nevertheless, Byng was eventually chosen because he was both willing and available.

The Governor General travelled the length and breadth of the country, meeting with Canadians wherever he went. He also immersed himself in Canada's culture and came to particularly love Ice hockey, hockey, rarely missing a game played by the Ottawa Senators (original), Ottawa Senators. He was also fond of the Royal Agricultural Winter Fair, held each year in Toronto, and established the Governor General's Cup to be presented at the competition. He was the first Governor General of Canada to appoint Canadians as his Aide-de-Camp, aides-de-camp (one of whom was future Governor General Georges Vanier) and approached his viceregal role with enthusiasm, gaining popularity with Canadians on top of that received from the men he had commanded on the European battlefields.

The Governor General travelled the length and breadth of the country, meeting with Canadians wherever he went. He also immersed himself in Canada's culture and came to particularly love Ice hockey, hockey, rarely missing a game played by the Ottawa Senators (original), Ottawa Senators. He was also fond of the Royal Agricultural Winter Fair, held each year in Toronto, and established the Governor General's Cup to be presented at the competition. He was the first Governor General of Canada to appoint Canadians as his Aide-de-Camp, aides-de-camp (one of whom was future Governor General Georges Vanier) and approached his viceregal role with enthusiasm, gaining popularity with Canadians on top of that received from the men he had commanded on the European battlefields.

King–Byng Affair

While it had been acceptable prior to the turn of the 20th century for Canadian governors general to involve themselves in political affairs, being, as they were, representatives of the Her Majesty's Government, King in his British Council, Byng's tenure as governor general was notable in that he became the first to step directly into political matters since the country had gained a degree of further autonomy following the First World War. In the summer of 1926 he denied the recommendation of his prime minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King, who sought to have parliament dissolved in order to avoid a Motion of no confidence, vote of non-confidence in his government. The Governor General's course of action in what came to be colloquially known as the ''King–Byng Affair'' remains debated, though the consensus amongst constitutional historians is that Byng's moves were appropriate under the circumstances. Mackenzie King, however, made much of the scenario and its outcome in 1926 Canadian federal election, the election that eventually followed on 14 September, in which King's Liberal Party of Canada, Liberal Party won a plurality of seats in the House of Commons, while Meighen lost his seat. As a result, King was once again appointed prime minister. At the 1926 Imperial Conference, King then went on to use Byng and his refusal to follow his prime minister's advice as the impetus for widespread constitutional change throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, British Commonwealth. Byng himself said of the matter: "I have to await the verdict of history to prove my having adopted a wrong course, and this I do with an easy conscience that, right or wrong, I have acted in the interests of Canada and implicated no one else in my decision."Post-viceregal life

Byng returned to England on 30 September 1926, and in January 1928 was created Viscount Byng of Vimy, of Thorpe-le-Soken in the County of Essex. Later that year, he was appointed as the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police and, before his retirement in 1931, introduced a number of changes to the force, including a system of promotion based on merit rather than length of service, improvement in discipline, retirement of inefficient senior officers, an irregularity to policemen's patrol, beats (which had previously allowed criminals to work out the system), police boxes, the extensive use of police cars, and a central radio control room. In July 1932, Byng was once more promoted in the British military to the rank of Field marshal (United Kingdom), field marshal—the highest rank an officer can attain—before he died suddenly of an abdominal blockage at Thorpe Hall on 6 June 1935. Lord Byng of Vimy was buried at the 11th Century Parish Church of St. Leonard in Beaumont-cum-Moze.Honours

Appointments

* 2 May 1902 – 6 June 1935: Royal Victorian Order, Member of the Royal Victorian Order (MVO) * 29 June 1906 – 1 January 1916: Order of the Bath, Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath (CB) ** 1 January 1916 – 1 January 1919: Knight Commander of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath (KCB) ** 1 January 1919 – 6 June 1935: Knight Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath (GCB) * March 1915 – July 1921: Order of St Michael and St George, Knight Commander of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George (KCMG) ** July 1921 – 6 June 1935: Knight Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George (GCMG) * 2 August 1921 – 5 August 1926: Scouts Canada#Organizational structure, Chief Scout for CanadaMedals

* 1884: Egypt Medal with El-Teb-Tamaai Medal bar, bar * 1897: Queen Victoria Diamond Jubilee Medal * 1899: Queen's South Africa Medal with Cape Colony, Tugela Heights, Orange Free State, Relief of Ladysmith, Laing's Nek, and Belfast bars * 1901: King's South Africa Medal with South Africa 1901 and 1902 bars * 1911: King George V Coronation Medal * 1918: 1914 Star with bar * 1919: British War Medal * 1919: Victory Medal (United Kingdom), Victory MedalAwards

* 6 February 1900: Mentioned in Despatches * 23 June 1902: Mentioned in Despatches * 11 December 1915: Mentioned in Despatches * 11 December 1915: Mentioned in Despatches * 22 December 1915: Mentioned in Despatches * 20 February 1918: Mentioned in Despatches * 20 July 1918: Mentioned in Despatches * 21 December 1918: Mentioned in DespatchesForeign honours

*Arms

Honorary military appointments

* 2 August 1921 – 5 August 1926: Colonel of the Governor General's Horse Guards * 2 August 1921 – 5 August 1926: Colonel of the Governor General's Foot Guards * 2 August 1921 – 5 August 1926: Colonel of the Canadian Grenadier GuardsHonorary degrees

* Ontario 1921: University of Toronto, Doctor of Laws (LL.D) * Alberta 1922: University of Alberta, Doctor of Laws (LL.D)Honorific eponyms

Geographic locations

* : Mount Byng * : Camp Byng, Roberts Creek, British Columbia, Roberts Creek * : Byng Place, Winnipeg * : Byng, Oklahoma, Byng * : Byng Avenue, Toronto * : Confederation Park, Saskatoon#History, Byng Avenue, SaskatoonSchools

* : Lord Byng Elementary School, Richmond, British Columbia, Richmond * : Lord Byng Secondary School, Vancouver * : General Byng School, Winnipeg * : Baron Byng High School, MontrealSee also

* List of World War I battlesNotes

References

Sources

* * * * * *External links

Website of the Governor General of Canada entry for Julian Byng

Portraits of Byng in the National Portrait Gallery

, - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Byng of Vimy, Julian H. G. Byng, 1st Viscount Governors General of Canada Commissioners of Police of the Metropolis People educated at Eton College British field marshals British Army personnel of the Mahdist War British Army cavalry generals of World War I Grand Officiers of the Légion d'honneur Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Members of the Royal Victorian Order Foreign recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States) Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) Royal Military College of Canada people Scouting and Guiding in Canada Viscounts in the Peerage of the United Kingdom Younger sons of earls 1862 births 1935 deaths People from Chipping Barnet 10th Royal Hussars officers King's Royal Rifle Corps officers British Militia officers South African Light Horse officers British Army personnel of the Second Boer War Chief Scouts of Canada Byng family, Julian People from Thorpe-le-Soken Graduates of the Staff College, Camberley Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Viscounts created by George V Military personnel from Hertfordshire Burials in Essex