Judiciary on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of

After the

After the

How the Legal System Works: The Structure of the Court System, State and Federal Courts

. In ''ABA Family Legal Guide''. may have different names and organization; trial courts may be called "courts of common plea", appellate courts "superior courts" or "commonwealth courts". The judicial system, whether state or federal, begins with a court of first instance, is appealed to an appellate court, and then ends at the court of last resort. In

court

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in acco ...

s that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

in legal cases.

Definition

The judiciary is the system ofcourts

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accorda ...

that interprets, defends, and applies the law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

in the name of the state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

. The judiciary can also be thought of as the mechanism for the resolution of disputes. Under the doctrine of the separation of powers

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typic ...

, the judiciary generally does not make statutory law

Statutory law or statute law is written law passed by a body of legislature. This is opposed to oral or customary law; or regulatory law promulgated by the executive or common law of the judiciary. Statutes may originate with national, stat ...

(which is the responsibility of the legislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its p ...

) or enforce law (which is the responsibility of the executive

Executive ( exe., exec., execu.) may refer to:

Role or title

* Executive, a senior management role in an organization

** Chief executive officer (CEO), one of the highest-ranking corporate officers (executives) or administrators

** Executive dir ...

), but rather interprets, defends, and applies the law to the facts of each case. However, in some countries the judiciary does make common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipres ...

.

In many jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' + 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, areas of jurisdiction apply to local, state, and federal levels.

J ...

s the judicial branch has the power to change laws through the process of judicial review

Judicial review is a process under which executive, legislative and administrative actions are subject to review by the judiciary. A court with authority for judicial review may invalidate laws, acts and governmental actions that are incomp ...

. Courts with judicial review power may annul the laws and rules of the state when it finds them incompatible with a higher norm, such as primary legislation, the provisions of the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

, treaties

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

or international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

. Judges constitute a critical force for interpretation and implementation of a constitution, thus in common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipres ...

countries creating the body of constitutional law.

History

This is a more general overview of the development of the judiciary and judicial systems over the course of history.Roman judiciary

Archaic Roman Law (650–264 BC)

The most important part was ''Ius Civile'' (Latin for "civil law"). This consisted of '' Mos Maiorum'' (Latin for "way of the ancestors") and ''Leges'' (Latin for "laws"). ''Mos Maiorum'' was the rules of conduct based on social norms created over the years by predecessors. In 451–449 BC, the ''Mos Maiorum'' was written down in theTwelve Tables

The Laws of the Twelve Tables was the legislation that stood at the foundation of Roman law. Formally promulgated in 449 BC, the Tables consolidated earlier traditions into an enduring set of laws.Crawford, M.H. 'Twelve Tables' in Simon Hornblowe ...

. ''Leges'' were rules set by the leaders, first the kings, later the popular assembly during the Republic. In these early years, the legal process consisted of two phases. The first phase, ''In Iure'', was the judicial process. One would go to the head of the judicial system (at first the priests as law was part of religion) who would look at the applicable rules to the case. Parties in the case could be assisted by jurists. Then the second phase would start, the ''Apud Iudicem''. The case would be put before the judges, which were normal Roman citizens in an uneven number. No experience was required as the applicable rules were already selected. They would merely have to judge the case.

Pre-classical Roman Law (264–27 BC)

The most important change in this period was the shift from priest topraetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected '' magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vari ...

as the head of the judicial system. The praetor would also make an edict

An edict is a decree or announcement of a law, often associated with monarchism, but it can be under any official authority. Synonyms include "dictum" and "pronouncement".

''Edict'' derives from the Latin edictum.

Notable edicts

* Telepinu Pro ...

in which he would declare new laws or principles for the year he was elected. This edict is also known as praetorian law.

Principate (27 BC–284 AD)

ThePrincipate

The Principate is the name sometimes given to the first period of the Roman Empire from the beginning of the reign of Augustus in 27 BC to the end of the Crisis of the Third Century in AD 284, after which it evolved into the so-called Dominate.

...

is the first part of the Roman Empire, which started with the reign of Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

. This time period is also known as the "classical era of Roman Law" In this era, the praetor's edict was now known as ''edictum perpetuum'', which were all the edicts collected in one edict by Hadrian. Also, a new judicial process came up: ''cognitio extraordinaria'' (Latin for "extraordinary process"). This came into being due to the largess of the empire. This process only had one phase, where the case was presented to a professional judge who was a representative of the emperor. Appeal was possible to the immediate superior.

During this time period, legal experts started to come up. They studied the law and were advisors to the emperor. They also were allowed to give legal advise on behalf of the emperor.

Dominate (284–565 AD)

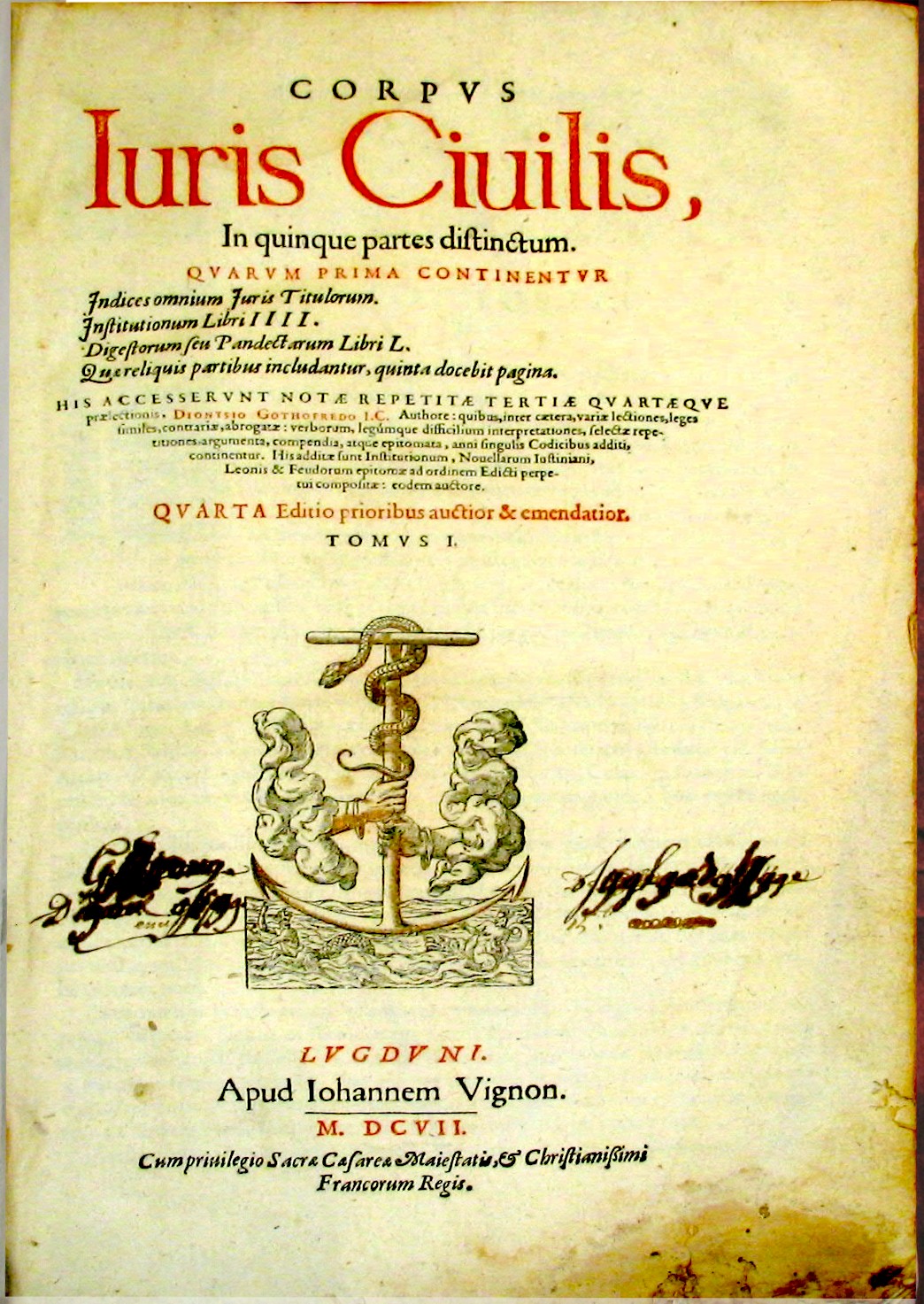

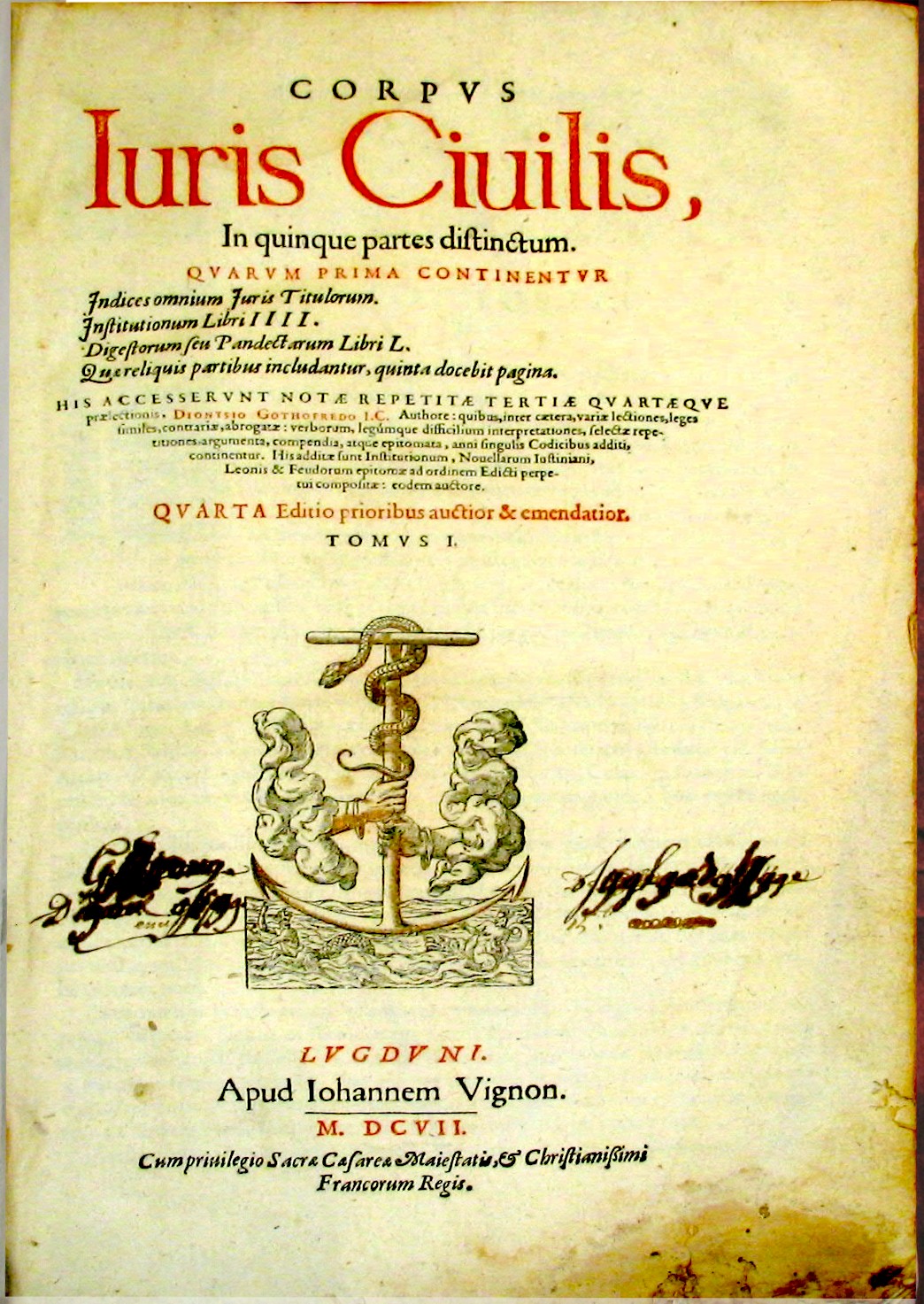

This era is also known as the "post-classical era of Roman law". The most important legal event during this era was the Codification by Justinianus: theCorpus Iuris Civilis

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. It is also sometimes referred ...

. This contained all Roman Law. It was both a collection of the work of the legal experts and commentary on it, and a collection of new laws. The ''Corpus Iuris Civilis'' consisted of four parts:

# ''Institutiones'': This was an introduction and a summary of Roman law.

# ''Digesta/Pandectae'': This was the collection of the edicts.

# ''Codex'': This contained all the laws of the emperors.

# ''Novellae'': This contained all new laws created.

Middle Ages

During the late Middle Ages, education started to grow. First education was limited to the monasteries and abbies, but expanded to cathedrals and schools in the city in the 11th century, eventually creating universities. The universities had five faculties: arts, medicine, theology, canon law and ''Ius Civile'', or civil law. Canon law, or ecclesiastical law are laws created by the Pope, head of the Roman Catholic Church. The last form was also called secular law, or Roman law. It was mainly based on the ''Corpus Iuris Civilis

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. It is also sometimes referred ...

,'' which had been rediscovered in 1070. Roman law was mainly used for "worldly" affairs, while canon law was used for questions related to the church.

The period starting in the 11th century with the discovery of the ''Corpus Iuris Civilis'' is also called the Scholastics

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translate ...

, which can be divided in the early and late scholastics. It is characterised with the renewed interest in the old texts.

''Ius Civile''

= Early scholastics (1070–1263)

= The rediscovery of the Digesta from the ''Corpus Iuris Civilis'' led the university of Bologna to start teaching Roman law. Professors at the university were asked to research the Roman laws and advise the Emperor and the Pope with regards to the old laws. This led to theGlossator

The scholars of the 11th- and 12th-century legal schools in Italy, France and Germany are identified as glossators in a specific sense. They studied Roman law based on the '' Digesta'', the ''Codex'' of Justinian, the ''Authenticum'' (an abridged ...

s to start translating and recreating the ''Corpus Iuris Civilis'' and create literature around it:

* ''Glossae'': translations of the old Roman laws

* ''Summae'': summaries

* ''Brocardica'': short sentences that made the old laws easier to remember, a sort of mnemonic

* ''Quaestio Disputata'' (''sic et non''): a dialectic method of seeking the argument and refute it.

Accursius wrote the ''Glossa Ordinaria

The ''Glossa Ordinaria'', which is Latin for "Ordinary .e. in a standard formGloss", is a collection of biblical commentaries in the form of glosses. The glosses are drawn mostly from the Church Fathers, but the text was arranged by scholars dur ...

'' in 1263, ending the early scholastics.

= Late scholastics (1263–1453)

= The successors of the Glossators were the Post-Glossators or Commentators. They looked at a subject in a logical and systematic way by writing comments with the texts, treatises and ''consilia'', which are advises given according to the old Roman law.Canon Law

= Early Scholastics (1070–1234)

= Canon law knows a few forms of laws: the ''canones'', decisions made by Councils, and the ''decreta'', decisions made by the Popes. The monk Gratian, one of the well-knowndecretist

In the history of canon law, a decretist was a student and interpreter of the ''Decretum Gratiani''. Like Gratian, the decretists sought to provide "a harmony of discordant canons" (''concordia discordantium canonum''), and they worked towards this ...

s, started to organise all of the church law, which is now known as the ''Decretum Gratiani

The ''Decretum Gratiani'', also known as the ''Concordia discordantium canonum'' or ''Concordantia discordantium canonum'' or simply as the ''Decretum'', is a collection of canon law compiled and written in the 12th century as a legal textbook b ...

'', or simply as ''Decretum''. It forms the first part of the collection of six legal texts, which together became known as the ''Corpus Juris Canonici

The ''Corpus Juris Canonici'' ( lit. 'Body of Canon Law') is a collection of significant sources of the canon law of the Catholic Church that was applicable to the Latin Church. It was replaced by the 1917 Code of Canon Law which went into effe ...

''. It was used by canonist

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

s of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

until Pentecost (19 May) 1918, when a revised '' Code of Canon Law'' (''Codex Iuris Canonici'') promulgated by Pope Benedict XV

Pope Benedict XV (Latin: ''Benedictus XV''; it, Benedetto XV), born Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa, name=, group= (; 21 November 185422 January 1922), was head of the Catholic Church from 1914 until his death in January 1922. His ...

on 27 May 1917 obtained legal force.

= Late Scholastics (1234–1453)

= TheDecretalist

In the history of canon law, the decretalists of the thirteenth century formed a school of interpretation that emphasised the decretals, those letters issued by the Popes ruling on matters of church discipline (''epistolae decretales''), in prefere ...

s, like the post-glossators for ''Ius Civile'', started to write treatises, comments and advises with the texts.

Ius Commune

Around the 15th century, a process of reception and acculturation started with both laws. The final product was known as ''Ius Commune

''Jus commune'' or ''ius commune'' is Latin for "common law" in certain jurisdictions. It is often used by civil law jurists to refer to those aspects of the civil law system's invariant legal principles, sometimes called "the law of the land" ...

''. It was a combination of canon law, which represented the common norms and principles, and Roman law, which were the actual rules and terms. It meant the creation of more legal texts and books and a more systematic way of going through the legal process. In the new legal process, appeal was possible. The process would be partially inquisitorial

An inquisitorial system is a legal system in which the court, or a part of the court, is actively involved in investigating the facts of the case. This is distinct from an adversarial system, in which the role of the court is primarily that of an ...

, where the judge would actively investigate all the evidence before him, but also partially adversarial, where both parties are responsible for finding the evidence to convince the judge.

After the

After the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

, lawmakers stopped interpretation of law by judges, and the legislature was the only body permitted to interpret the law; this prohibition was later overturned by the Napoleonic Code.

Functions of the judiciary in different law systems

In common law jurisdictions, courts interpret law; this includes constitutions, statutes, and regulations. They also make law (but in a limited sense, limited to the facts of particular cases) based upon prior case law in areas where the legislature has not made law. For instance, thetort

A tort is a civil wrong that causes a claimant to suffer loss or harm, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act. Tort law can be contrasted with criminal law, which deals with criminal wrongs that are punishable ...

of negligence

Negligence (Lat. ''negligentia'') is a failure to exercise appropriate and/or ethical ruled care expected to be exercised amongst specified circumstances. The area of tort law known as ''negligence'' involves harm caused by failing to act as a ...

is not derived from statute law in most common law jurisdictions. The term ''common law'' refers to this kind of law. Common law decisions set precedent for all courts to follow. This is sometimes called ''stare decisis''.

Country-specific functions

In the United States court system, the Supreme Court is the final authority on the interpretation of the federal Constitution and all statutes and regulations created pursuant to it, as well as the constitutionality of the various state laws; in the US federal court system, federal cases are tried intrial court

A trial court or court of first instance is a court having original jurisdiction, in which trials take place. Appeals from the decisions of trial courts are usually made by higher courts with the power of appellate review (appellate courts). Mos ...

s, known as the US district courts, followed by appellate court

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of ...

s and then the Supreme Court. State courts, which try 98% of litigation,American Bar Association (2004)How the Legal System Works: The Structure of the Court System, State and Federal Courts

. In ''ABA Family Legal Guide''. may have different names and organization; trial courts may be called "courts of common plea", appellate courts "superior courts" or "commonwealth courts". The judicial system, whether state or federal, begins with a court of first instance, is appealed to an appellate court, and then ends at the court of last resort. In

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, the final authority on the interpretation of the law is the Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

for administrative cases, and the Court of Cassation

A court of cassation is a high-instance court that exists in some judicial systems. Courts of cassation do not re-examine the facts of a case, they only interpret the relevant law. In this they are appellate courts of the highest instance. In th ...

for civil and criminal cases.

In the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, the final authority on the interpretation of the law is the National People's Congress

The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China (NPC; ), or simply the National People's Congress, is constitutionally the supreme state authority and the national legislature of the People's Republic of China.

With 2,9 ...

.

Other countries such as Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

have mixed systems that include lower courts, appeals courts, a cassation court (for criminal law) and a Supreme Court. In this system the Supreme Court is always the final authority, but criminal cases have four stages, one more than civil law does. On the court sits a total of nine justices. This number has been changed several times.

Judicial systems by country

Japan

Japan's process for selecting judges is longer and more stringent than in various countries, like theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

and in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

. Assistant judges are appointed from those who have completed their training at the Legal Training and Research Institute located in Wako. Once appointed, assistant judges still may not qualify to sit alone until they have served for five years, and have been appointed by the Supreme Court of Japan

The , located in Hayabusachō, Chiyoda, Tokyo, is the highest court in Japan. It has ultimate judicial authority to interpret the Japanese constitution and decide questions of national law. It has the power of judicial review, which allows it t ...

. Judges require ten years of experience in practical affairs, as a public prosecutor or practicing attorney. In the Japanese judicial branch there is the Supreme Court, eight high courts, fifty district courts, fifty family courts, and 438 summary courts.

Mexico

Justices of theMexican Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation ( es, Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación (SCJN) is the Mexican institution serving as the country's federal high court and the spearhead organisation for the judiciary of the Mexican Federal Gov ...

are appointed by the President of Mexico

The president of Mexico ( es, link=no, Presidente de México), officially the president of the United Mexican States ( es, link=no, Presidente de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos), is the head of state and head of government of Mexico. Under the Co ...

, and then are approved by the Mexican Senate

The Senate of the Republic, ( es, Senado de la República) constitutionally Chamber of Senators of the Honorable Congress of the Union ( es, Cámara de Senadores del H. Congreso de la Unión), is the upper house of Mexico's bicameral Congre ...

to serve for a life term. Other justices are appointed by the Supreme Court and serve for six years. Federal courts consist of the 11 ministers of the Supreme Court, 32 circuit tribunals and 98 district courts. The Supreme Court of Mexico is located in Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital city, capital and primate city, largest city of Mexico, and the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North Amer ...

. Supreme Court Judges must be of ages 35 to 65 and hold a law degree during the five years preceding their nomination.

United States

United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

justices are appointed by the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

and approved by the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

. The Supreme Court justices serve for life term or until retirement. The Supreme Court is located in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

The United States federal court system

The federal judiciary of the United States is one of the three branches of the federal government of the United States organized under the Constitution of the United States, United States Constitution and Law of the United States, laws of the fed ...

consists of 94 federal judicial districts. The 94 districts are then divided up into twelve regional circuits. The United States has five different types of courts that are considered subordinate to the Supreme Court: United States bankruptcy court

United States bankruptcy courts are courts created under Article I of the United States Constitution. The current system of bankruptcy courts was created by the United States Congress in 1978, effective April 1, 1984. United States bankruptcy c ...

s, United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (in case citations, Fed. Cir. or C.A.F.C.) is a United States court of appeals that has special appellate jurisdiction over certain types of specialized cases in the U.S. federal court ...

, United States Court of International Trade

The United States Court of International Trade (case citations: Int'l Trade or Intl. Trade) is a U.S. federal court that adjudicates civil actions arising out of U.S. customs and international trade laws. Seated in New York City, it exercises ...

, United States courts of appeals

The United States courts of appeals are the intermediate appellate courts of the United States federal judiciary. The courts of appeals are divided into 11 numbered circuits that cover geographic areas of the United States and hear appeals f ...

, and United States district court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district, which each cover one U.S. state or, in some cases, a portion of a state. Each district co ...

s.

Immigration courts are not part of the judicial branch; immigration judges are employees of the Executive Office for Immigration Review

The Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) is a sub-agency of the United States Department of Justice whose chief function is to conduct removal proceedings in immigration courts and adjudicate appeals arising from the proceedings. These ...

, part of the United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United Stat ...

in the executive branch.

Each state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

, district

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or county, counties, several municipality, municipa ...

and inhabited territory also has its own court system

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordanc ...

operating within the legal framework of the respective jurisdiction, responsible for hearing cases regarding state and territorial law. All these jurisdictions also have their own supreme courts (or equivalent) which serve as the highest courts of law within their respective jurisdictions.

See also

*Bench (law)

Bench used in a legal context can have several meanings. First, it can simply indicate the location in a courtroom where a judge sits. Second, the term bench is a metonym used to describe members of the judiciary collectively, or the judges ...

* Supreme court

* Political corruption

* Judicial independence

* Judicial review

Judicial review is a process under which executive, legislative and administrative actions are subject to review by the judiciary. A court with authority for judicial review may invalidate laws, acts and governmental actions that are incomp ...

* Rule according to higher law

* Rule of law

References

Further reading

* Cardozo, Benjamin N. (1998). ''The Nature of the Judicial Process

''The Nature of the Judicial Process'' is a legal classic written by Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, and New York Court of Appeals Chief Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo in 1921. It was compiled from The Storrs Lectures deliver ...

''. New Haven: Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day, and became an official department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and operationally autonomous.

, Yale Universi ...

.

* Feinberg, Kenneth, Jack Kress, Gary McDowell, and Warren E. Burger (1986). ''The High Cost and Effect of Litigation'', 3 vols.

* Frank, Jerome (1985). ''Law and the Modern Mind''. Birmingham, AL: Legal Classics Library.

* Levi, Edward H. (1949) ''An Introduction to Legal Reasoning''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press is the largest and one of the oldest university presses in the United States. It is operated by the University of Chicago and publishes a wide variety of academic titles, including ''The Chicago Manual of Style'', ...

.

* Marshall, Thurgood (2001). ''Thurgood Marshall: His Speeches, Writings, Arguments, Opinions and Reminiscences''. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books.

* McCloskey, Robert G., and Sanford Levinson (2005). ''The American Supreme Court'', 4th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

* Miller, Arthur S. (1985). ''Politics, Democracy and the Supreme Court: Essays on the Future of Constitutional Theory''. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

*

* Tribe, Laurence (1985). ''God Save This Honorable Court: How the Choice of Supreme Court Justices Shapes Our History''. New York: Random House.

* Zelermyer, William (1977). ''The Legal System in Operation''. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing.

External links

* * * {{Authority control Separation of powers