Judah Ben Solomon Hai Alkalai on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

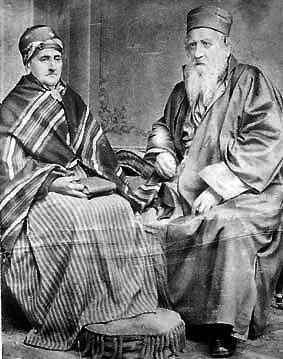

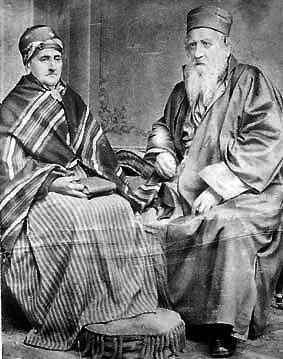

Judah ben Solomon Chai Alkalai (1798 – October 1878) was a

Judah ben Solomon Chai Alkalai (1798 – October 1878) was a

Judah ben Solomon Chai Alkalai (1798 – October 1878) was a

Judah ben Solomon Chai Alkalai (1798 – October 1878) was a Sephardic

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), ...

Jewish rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

, and one of the influential precursors of modern Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a Nationalism, nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is ...

along with the Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

n Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer

Zvi (Zwi) Hirsch Kalischer (24 March 1795 – 16 October 1874) was an Orthodox German rabbi who expressed views, from a religious perspective, in favour of the Jewish re-settlement of the Land of Israel, which predate Theodor Herzl and the Zionist ...

. Although he was a Sephardic Jew, he played an important role in a process widely attributed to the Ashkenazi

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

Jews. Alkalai became noted through his advocacy in favor of the restoration of the Jews to the Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Isra ...

. By reason of some of his projects, he may justly be regarded as one of the precursors of the modern Zionists such as Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern p ...

.

Biography

Yehuda Alkalai was born inSarajevo

Sarajevo ( ; cyrl, Сарајево, ; ''see Names of European cities in different languages (Q–T)#S, names in other languages'') is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 275,524 in its a ...

in 1798. At that time Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and He ...

was ruled by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

.

He studied in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, which also belonged to the Ottoman Turkish Empire, under different rabbis and came under the influence of the Kabbalah

Kabbalah ( he, קַבָּלָה ''Qabbālā'', literally "reception, tradition") is an esoteric method, discipline and Jewish theology, school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ( ''Məqūbbāl'' "rece ...

.

In 1825 he became reader

A reader is a person who reads. It may also refer to:

Computing and technology

* Adobe Reader (now Adobe Acrobat), a PDF reader

* Bible Reader for Palm, a discontinued PDA application

* A card reader, for extracting data from various forms of ...

and teacher at the Sephardic community of Semlin, and then its rabbi a few years later. Semlin, today's Zemun

Zemun ( sr-cyrl, Земун, ; hu, Zimony) is a municipality in the city of Belgrade. Zemun was a separate town that was absorbed into Belgrade in 1934. It lies on the right bank of the Danube river, upstream from downtown Belgrade. The developme ...

district

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or counties, several municipalities, subdivisions o ...

of the Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

n capital Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

, was at that time part of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

's Military Frontier

The Military Frontier (german: Militärgrenze, sh-Latn, Vojna krajina/Vojna granica, Војна крајина/Војна граница; hu, Katonai határőrvidék; ro, Graniță militară) was a borderland of the Habsburg monarchy and l ...

. At the time of Alkalai's arrival, the region was experiencing strong nationalist movements, and the Serbian War of Independence, which led to the creation of a new Serbian state after centuries of Ottoman occupation, gave impetus to new nationalistic ideas among Balkan Jews such as Alkalai.

In 1852, Alkalai established the Society of the Settlement of Eretz Yisrael in London.

In 1871 Alkalai visited Jerusalem and established another short-lived colonization society. In 1874, at the age of 76, he moved there with his wife. He died in 1878, days after his native Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and He ...

was occupied by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and was buried in the ancient Mount of Olives Jewish Cemetery

The Jewish Cemetery on the Mount of Olives is the oldest and most important Jewish cemetery in Jerusalem. It is approximately five centuries old, having been first leased from the Jerusalem Islamic Waqf in the sixteenth century. ...

.

Influence on Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern p ...

's paternal grandfather, Simon Loeb Herzl, reportedly attended Alkalai's synagogue in Semlin and the two frequently visited. Grandfather Simon Loeb Herzl "had his hands on" one of the first copies of Alkalai's 1857 work prescribing the "return of the Jews to the Holy Land and renewed glory of Jerusalem." Contemporary scholars conclude that Herzl's own implementation of modern Zionism was undoubtedly influenced by that relationship.

Religious base for activism

Alkalai's view of Jewish return to the Land of Israel was areligious

Religion is usually defined as a social system, social-cultural system of designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morality, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sacred site, sanctified places, prophecy, prophecie ...

one. He maintained, based on an ample body of religious literature, that the coming of the Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

and divine redemption of the Jews require their return to the Promised Land

The Promised Land ( he, הארץ המובטחת, translit.: ''ha'aretz hamuvtakhat''; ar, أرض الميعاد, translit.: ''ard al-mi'ad; also known as "The Land of Milk and Honey"'') is the land which, according to the Tanakh (the Hebrew ...

. His Kabbalistic view made him specifically assert that the year 1840 was the Year of Redemption, which was not a single year, but "a century, from this day until 1939", representing the "days of the Messiah". Unless powerful practical steps were taken, this opportunity would be lost, and the next extended "year" starting in 1940 would be one of great hardship when "with an outpouring of wrath will gather our dispersed". The outcome - the return to the Promised Land - would be the same, but under much harsher circumstances.

Political proto-Zionism

Alkalai's began by writing inLadino

Ladino, derived from Latin, may refer to:

* The register of Judaeo-Spanish used in the translation of religious texts, such as the Ferrara Bible

*Ladino people, a socio-ethnic category of Mestizo or Hispanicized people in Central America especi ...

, which limited his outreach to the rather small European Sephardic community. Only later did he adopt the much wider understood Hebrew language

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, and he only intensified his political work after the age of 60, at a time when a wider audience seemed to be ready to accept his ideas.

In his ''Shalom Yerushalayim'' (The Peace of Jerusalem), 1840, he replies to those who attacked his book, ''Darkhei No'am'' (The Pleasant Paths), which treated of the duty of tithes

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more r ...

. Another work, ''Minchat Yehudah'' (The Offering of Judah), Vienna, 1843, is a panegyric

A panegyric ( or ) is a formal public speech or written verse, delivered in high praise of a person or thing. The original panegyrics were speeches delivered at public events in ancient Athens.

Etymology

The word originated as a compound of grc, ...

on Montefiore Montefiore, Montifiore, and Montefiori is a surname associated with the Montefiore family, Sephardi Jews who were diplomats and bankers all over Europe and who originated from the Iberian Peninsula, namely Spain and Portugal, and also France, Morocc ...

and Crémieux, who had rescued the Jews of Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

from a blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mur ...

accusation. The 1840 Damascus Affair reassured Alkalai that the Jews needed a land of their own to act as a safe haven, but at the same time the positive effects of the intervention by the European powers and by a united front of European Jewish notables also convinced him about the usefulness of foreign support to the success of such an enterprise. In ''Raglei mevasser'' he specifically wrote that "The salvation of Israel lies in addressing to the kings of the earth a general request for the welfare of our nation and our holy cities, and for our return in repentance to the house of our mother... our salvation will come rapidly from the kings of the earth."

His plan called for the creation of a representative "Assembly of Jewish Notables" who would advocate the case of a Jewish return to the Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Isra ...

, and for the settlement of the land using funds collected from Jewish communities in form of a tithe, a tenth of one's income, a practice called ''halukka

The ''halukka'', also spelled ''haluka'', ''halukkah'' or ''chalukah'' ( he, חלוקה) was an organized collection and distribution of charity funds for Jewish residents of the Land of Israel (the Holy Land).

General method of operation

Symp ...

'' and already used for supporting the religious groups inhabiting the Jewish Four Holy Cities

The Four Holy Cities of Judaism are the cities of Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed and Tiberias which were the four main centers of Jewish life after the Ottoman conquest of Palestine.

According to the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia: "Since the sixteenth cen ...

. In ''Minchat Yehudah'' Alkalai proposes a return to the roots: the restoration of Hebrew as the Jewish national language, the recovery of land of Israel by purchasing it much like Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jew ...

did with the cave and field of Machpelah in Hebron

Hebron ( ar, الخليل or ; he, חֶבְרוֹן ) is a Palestinian. city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Nestled in the Judaean Mountains, it lies above sea level. The second-largest city in the West Bank (after East J ...

, and agriculture as the basis for renewed Jewish settlement. For practical reasons and in spite of being a traditionalist who opposed Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous searc ...

, Alkalai attempted to achieve national unity. Eventually Zionism would apply several of Alkalai's principles, such as the revival of Hebrew, the purchase of land, the pursuit of agricultural labour (though motivated by a "return to the land" of the Jews, seen as alienated from manual work, nature, and their ancestral land, rather than just as a means of immigrant integration and sustenance), and a political effort towards receiving support from the world powers, and for uniting all Jews behind Zionist ideals.

Apart from creating an impressive literary output, Alkalai also toured Western Europe in 1851–1852, including Great Britain, and spread his message among local communities. The success was small among fellow Jews, not least due to other rabbis who considered his idea of human acts constituting a catalyst for the coming of the Messiah as heretical, but British Christian Zionists helped him found a short-lived colonisation society.

His work, ''Goral la-Adonai'' (A Lot for the Lord), published in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

in 1857, is a treatise on the restoration of the Jews to their ancestral homeland, and suggests methods for the betterment of conditions in the Land of Israel. After a somewhat able homiletic

In religious studies, homiletics ( grc, ὁμιλητικός ''homilētikós'', from ''homilos'', "assembled crowd, throng") is the application of the general principles of rhetoric to the specific art of public preaching. One who practices or ...

al discussion of the Messianic problem, in which he shows considerable knowledge of the traditional writers, Alkalai suggests the formation of a joint-stock company

A joint-stock company is a business entity in which shares of the company's capital stock, stock can be bought and sold by shareholders. Each shareholder owns company stock in proportion, evidenced by their share (finance), shares (certificates ...

, such as a steamship or railroad trust, whose endeavor it should be to induce the Ottoman sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

to cede Land of Israel to the Jews as a tributary country, on a plan similar to that on which the Danubian Principalities

The Danubian Principalities ( ro, Principatele Dunărene, sr, Дунавске кнежевине, translit=Dunavske kneževine) was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th ce ...

were governed. To this suggestion are appended the commendations of numerous Jewish scholars of various schools of thought. The problem of the restoration of Palestine to the Jews was also discussed by Alkalai in ''Shema' Yisrael'' (Hear, O Israel), 1861 or 1862, and in ''Harbinger of Good Tidings'' (compare ''Jewish Chronicle

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

'', 1857, p. 1198, where his name is spelled Alkali).

Alkalai joined the first Jewish organisation for the agricultural settlement of the Land of Israel, the Kolonisations-Verein für Palästina (Association for the Colonisation of Palestine), established in Frankfurt (Oder)

Frankfurt (Oder), also known as Frankfurt an der Oder (), is a city in the German state of Brandenburg. It has around 57,000 inhabitants, is one of the easternmost cities in Germany, the fourth-largest city in Brandenburg, and the largest German ...

in 1860 by Chaim Lorje. Although Alkalai and others, such as Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer, put much energy into promoting its goals, the association couldn't reach any tangible results and soon dispersed.

See also

*Yehuda Bibas Yehuda Aryeh Leon Bibas (or Judah Bibas) ( he, יהודה אריה ליאון ביבאס) (1789 – April 6, 1852) was a Sephardic rabbi, the rabbi of Corfu and was the first of the precursors of modern Zionism.

Biography

Early life

Bibas was ...

*Arthur Hertzberg

Arthur Hertzberg (June 9, 1921 – April 17, 2006) was a Conservative rabbi and prominent Jewish-American scholar and activist.

Biography

Avraham Hertzberg was born in Lubaczów, Poland, the eldest of five children, and left Europe in 1926 with ...

*Proto-Zionism

Proto-Zionism (or Forerunner of Zionism; he, מְבַשְרֵי הציונות, pronounced: ''Mevasrei ha-Tzionut'') is a term attributed to the ideas of a group of men deeply affected by the idea of modern nationalism spread in Europe in the 1 ...

References

Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Alkalai, Judah 1798 births 1878 deaths Sephardi Jews from the Ottoman Empire Sephardi rabbis in Ottoman Palestine 19th-century rabbis from the Ottoman Empire Burials at the Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives Jewish Austrian writers Sephardi rabbis Forerunners of Zionism Austro-Hungarian Sephardi Jews Jews in Ottoman Palestine Rabbis in Ottoman Syria Rabbis from Sarajevo Judaeo-Spanish-language writers Hebrew-language writers Jewish Bosnian history Jewish Serbian history Bosnia and Herzegovina Sephardi Jews