Juan Santamaría on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Juan Santamaría Rodríguez (August 29, 1831 – April 11, 1856) was a

The nationally recognized independence day in Costa Rica is September 15th, the anniversary of the day Central America declared independence from Spain in 1821. However Costa Rican independence has become synonymous with the Juan Santamaría, the Second Battle of Rivas and the Filibuster War, because this was the only time the country fought to remain a sovereign nation. In 1891, on September 15th, a statue of Juan Santamaría was erected in Alajuela to commemorate him, and on many later Independence Day celebrations the government further honored and celebrated Juan Santamaría for his heroism in the struggle against William Walker. Additionally, the anniversary of his death, April 11th, is a national holiday: Juan Santamaría Day.

The nationally recognized independence day in Costa Rica is September 15th, the anniversary of the day Central America declared independence from Spain in 1821. However Costa Rican independence has become synonymous with the Juan Santamaría, the Second Battle of Rivas and the Filibuster War, because this was the only time the country fought to remain a sovereign nation. In 1891, on September 15th, a statue of Juan Santamaría was erected in Alajuela to commemorate him, and on many later Independence Day celebrations the government further honored and celebrated Juan Santamaría for his heroism in the struggle against William Walker. Additionally, the anniversary of his death, April 11th, is a national holiday: Juan Santamaría Day.

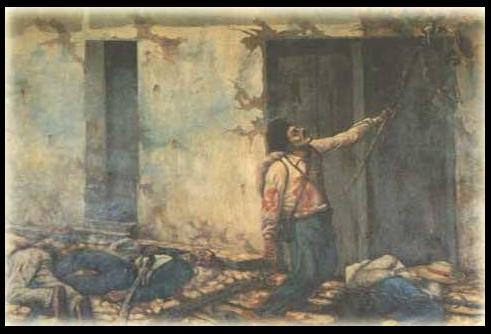

The two most widely known physical depictions of Juan Santamaría are the bronze statue in Alajuela that shows him in his soldier's uniform, carrying the torch he used to burn the enemy stronghold, and a painting by Enrique Echandi in which he is shown dying as he lights the building on fire. In the statue, Santamaría is bravely advancing while holding the torch he would use to light the building on fire. Around the base of the statue are depictions of him volunteering for this dangerous task, and his dying in the battle. In addition to the artists renderings of the battle, the statue also has huge bronze lion's heads around the base. The lion is a common symbol of courage and strength, and the choice to include this symbolism solidifies the statues depiction of Juan Santamaría as a courageous and brave hero. The statue portrays him as a strong and heroic man willing to die for Costa Rica, while the painting, on the other hand, portrays him more as a martyr for Costa Rican independence. In Echandi's painting titled "La Quema del Méson por Juan Santamaría", or in English "The Burning of the Hostel by Juan Santamaría", Santamaría is shown covered in blood as he sinks to his knees, dying while lighting the building on fire with a torch. In the painting, he is also notably of African descent as it shows his darker skin and dark hair. This painting, additionally, shows the greater carnage of the battle, not just the death of Santamaría, with other dead soldiers and weapons on the ground around Santamaría. The painting depicting his last moments portrays Santamaría as a tragic hero, and a sacrifice made for independence, instead of the powerful and inspiring image of Santamaría in the bronze statue.

The two most widely known physical depictions of Juan Santamaría are the bronze statue in Alajuela that shows him in his soldier's uniform, carrying the torch he used to burn the enemy stronghold, and a painting by Enrique Echandi in which he is shown dying as he lights the building on fire. In the statue, Santamaría is bravely advancing while holding the torch he would use to light the building on fire. Around the base of the statue are depictions of him volunteering for this dangerous task, and his dying in the battle. In addition to the artists renderings of the battle, the statue also has huge bronze lion's heads around the base. The lion is a common symbol of courage and strength, and the choice to include this symbolism solidifies the statues depiction of Juan Santamaría as a courageous and brave hero. The statue portrays him as a strong and heroic man willing to die for Costa Rica, while the painting, on the other hand, portrays him more as a martyr for Costa Rican independence. In Echandi's painting titled "La Quema del Méson por Juan Santamaría", or in English "The Burning of the Hostel by Juan Santamaría", Santamaría is shown covered in blood as he sinks to his knees, dying while lighting the building on fire with a torch. In the painting, he is also notably of African descent as it shows his darker skin and dark hair. This painting, additionally, shows the greater carnage of the battle, not just the death of Santamaría, with other dead soldiers and weapons on the ground around Santamaría. The painting depicting his last moments portrays Santamaría as a tragic hero, and a sacrifice made for independence, instead of the powerful and inspiring image of Santamaría in the bronze statue.

Costa Rican national archives

These documents are two separate lists of soldiers from Alajuela; the name Juan Santamaría can be seen on both. A document listing the names and causes of death for soldiers in the Costa Rican army, however, is one of the reasons some doubt the story of Juan Santamaría's actions in the Second Battle of Rivas. This document written in 1858 by the chaplain of the Costa Rican army, Priest Rafael Francisco Calvo, listed a man named Juan Santamaría from Alajuela who died from cholera, a common deadly illness at the time. A doctor who lived with Calvo later in his life named Rafael Calderón Muñoz claims when he asked the priest about the man who died of cholera, Calvo claimed it was a different Juan Santamaría than the hero. Other documents brought forward that support Calvo's claim that it was a different Juan Santamaría include a military census listing five different people named Juan Santamaría from Alajuela, and a different report of people who died between April and May of 1856 that listed the death of a Juan Santamaría who died in Rivas. Despite lacking proof of details, there is a strong and consistent oral tradition that Juan Santamaría existed, he was present at the Second Battle of Rivas, he was one of the people who participated in burning down the building, and he died in the act.

Museo Histórico Juan Santamaría

(Selection of languages, including English) {{DEFAULTSORT:Santamaria, Juan 1831 births 1856 deaths History of Costa Rica People from Alajuela National Heroines and Heroes of Nicaragua National symbols of Costa Rica

drummer

A drummer is a percussionist who creates music using drum

The drum is a member of the percussion group of musical instruments. In the Hornbostel-Sachs classification system, it is a membranophone. Drums consist of at least one mem ...

in the Costa Rica

Costa Rica (, ; ; literally "Rich Coast"), officially the Republic of Costa Rica ( es, República de Costa Rica), is a country in the Central American region of North America, bordered by Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the no ...

n army, officially recognized as the national hero

The title of Hero is presented by various governments in recognition of acts of self-sacrifice to the state, and great achievements in combat or labor. It is originally a Soviet-type honor, and is continued by several nations including Belarus, Ru ...

of his country for his actions in the 1856 Second Battle of Rivas

The Second Battle of Rivas occurred on 11 April 1856 between Costa Rican militia under General Mora and the Nicaraguan forces of American mercenary William Walker. The lesser known First Battle of Rivas took place on the 29 June 1855 between ...

, in the Filibuster War

The Filibuster War or Walker affair was a military conflict between filibustering multinational troops stationed in Nicaragua and a coalition of Central American armies. An American mercenary William Walker invaded Nicaragua in 1855 with a sma ...

. He died in the battle carrying a torch he used to light the enemy stronghold on fire, securing a victory for Costa Rica against American mercenary William Walker and his imperialist forces. Thirty five years after his death, he began to be idealized and was used as a propaganda tool to inspire Costa Rican nationalism

Costa Rican nationalism is the nationalist vision of the cultural and national identity of Costa Rica. According to scholars such as Tatiana Lobo, Carmen Murillo and Giovanna Giglioli, Costa Rican nationalism is based on two main myths; rural d ...

. A national holiday in Costa Rica, Juan Santamaría Day, is held annually on April 11th to commemorate his death.

On September 15, 1891, a huge bronze statue of the hero was erected in Juan Santamaría de Alajuela Park in his home town, Alajuela

Alajuela () is a district in the Alajuela canton of the Alajuela Province of Costa Rica. As the seat of the Municipality of Alajuela canton, it is awarded the status of city. By virtue of being the city of the first canton of the province, it i ...

. Later, the main airport of Costa Rica, and the historical museum of Alajuela were named after him, and many literary, musical, and art works have been created in his honor. Along with commemorating his heroic acts, many historical studies have been done to investigate the true identity and actions of Juan Santamaría.

Life

Santamaría was born in the city ofAlajuela

Alajuela () is a district in the Alajuela canton of the Alajuela Province of Costa Rica. As the seat of the Municipality of Alajuela canton, it is awarded the status of city. By virtue of being the city of the first canton of the province, it i ...

on August 29, 1831. His mother was María Manuela Santamaría, and his father was unknown. He went to elementary school in Alajuela before working from a young age. Santamaría had many jobs in Alajuela such as a sweets vendor, laborer, coffee picker, and, finally, a drummer in the military band of Alajuela, which lead him to become a drummer for the Costa Rican Army. He was a drummer boy in the Costa Rican army until his death in the Second Battle of Rivas

The Second Battle of Rivas occurred on 11 April 1856 between Costa Rican militia under General Mora and the Nicaraguan forces of American mercenary William Walker. The lesser known First Battle of Rivas took place on the 29 June 1855 between ...

while completing the heroic deed for which he is remembered.

Participation in the Filibuster War

The war began when William Walker, an American filibuster, or person engaged in unauthorized warfare against a foreign country, overthrew the government ofNicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

in 1856 and attempted to conquer the other nations in Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

, including Costa Rica, in order to form a private slaveholding empire. Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora Porras

Juan Rafael Mora Porras (8 February 1814, San José, Costa Rica – 30 September 1860) was President of Costa Rica from 1849 to 1859.

Life and career

He first assumed the presidency following the resignation of his younger brother, Miguel M ...

called upon the general population to take up arms and march north to Nicaragua to fight against the foreign invader. This started the Filibuster War

The Filibuster War or Walker affair was a military conflict between filibustering multinational troops stationed in Nicaragua and a coalition of Central American armies. An American mercenary William Walker invaded Nicaragua in 1855 with a sma ...

. Santamaría, a poor laborer and the illegitimate son of a single mother joined the army as a drummer boy. The troops nicknamed him "el erizo" ("the hedgehog") on account of his spiked hair.

After routing a small contingent of Walker's soldiers at Santa Rosa

Santa Rosa is the Italian, Portuguese and Spanish name for Saint Rose.

Santa Rosa may also refer to:

Places Argentina

*Santa Rosa, Mendoza, a city

* Santa Rosa, Tinogasta, Catamarca

* Santa Rosa, Valle Viejo, Catamarca

* Santa Rosa, La Pampa

* S ...

, Guanacaste, the Costa Rican troops continued marching north and reached the city of Rivas, Nicaragua

Rivas () is a city and municipality in southwestern Nicaragua on the Isthmus of the same name. The city proper is the capital of the Department of Rivas and administrative centre for the surrounding municipality of the same name.

Climate

Rivas ...

, on April 8, 1856. The battle that ensued is known as the Second Battle of Rivas

The Second Battle of Rivas occurred on 11 April 1856 between Costa Rican militia under General Mora and the Nicaraguan forces of American mercenary William Walker. The lesser known First Battle of Rivas took place on the 29 June 1855 between ...

. Combat was fierce and the Costa Ricans were not able to drive Walker's men out of a building near the town center from which they commanded an advantageous firing position.

According to the traditional account, on April 11, Salvadoran General José María Cañas suggested that one of the soldiers advance towards the hostel with a torch and set it on fire. Some soldiers tried and failed, but Santamaría finally volunteered on the condition that in the event of his death, someone would look after his mother. He then advanced and was mortally wounded by enemy fire. Before expiring he succeeded, however, in setting fire to the building, thus contributing decisively to the Costa Rican victory at Rivas.

This account is apparently supported by a petition for a state pension filed in November 1857 by Santamaría's mother, as well as by government documents showing that the pension was granted. Various historians, however, have questioned whether the account is accurate and whether Santamaria died under different circumstances. At any rate, towards the end of the 19th century, Costa Rican intellectuals and politicians seized on the war against Walker and on the figure of Santamaría for nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

purposes.

National symbolism

Juan Santamaría's Initial Fame

Following his death, the Filibuster War raged on, eventually ending in the defeat of William Walker and his forces. Juan Santamaría's actions, however, were not mentioned in Costa Rican national discourse until 1885, 29 years after his death. His name was first mentioned in an article in ''El Diario de Costa Rica,'' a national newspaper, titled "Un Heróe Anómino". This article was written in response to the threats to Costa Rican independence from Guatemala's dictator at the time,Justo Rufino Barrios

Justo Rufino Barrios Auyón (19 July 1835 – 2 April 1885) was a Guatemalan politician and military general who served as President of Guatemala from 1873 to his death in 1885. He was known for his liberal reforms and his attempts to reuni ...

; Barrios declared he would use force to unite the countries of Central America in the Union of Central America if they did not consent on their own to unity. "Un Heróe Anónimo" was written about Santamaría's sacrifice and two other generals from the Filibuster War to inspire and mobilize the population of Costa Rica against the threat to their sovereignty. This call to arms was repeated as the article was published in other official newspapers, and the President of Costa Rica at the time declared a new national steamship would bear the name The Juan Santamaría in the hero's honor. Juan Santamaría was used as a figurehead around which Costa Rican leaders developed a national identity to rally support in defending Costa Rican sovereignty. While Costa Rican troops never even fought against Guatemalan forces due to the defeat of Barrios by troops from El Salvador, the story of Juan Santamaría remained a central feature of Costa Rican national identity, and he was soon declared a national hero. Through written press, festivals in his honor, and the promotion of his story by the education system, Juan Santamaría became a symbol of Costa Rica.

Becoming a symbol for Costa Rican Independence

The nationally recognized independence day in Costa Rica is September 15th, the anniversary of the day Central America declared independence from Spain in 1821. However Costa Rican independence has become synonymous with the Juan Santamaría, the Second Battle of Rivas and the Filibuster War, because this was the only time the country fought to remain a sovereign nation. In 1891, on September 15th, a statue of Juan Santamaría was erected in Alajuela to commemorate him, and on many later Independence Day celebrations the government further honored and celebrated Juan Santamaría for his heroism in the struggle against William Walker. Additionally, the anniversary of his death, April 11th, is a national holiday: Juan Santamaría Day.

The nationally recognized independence day in Costa Rica is September 15th, the anniversary of the day Central America declared independence from Spain in 1821. However Costa Rican independence has become synonymous with the Juan Santamaría, the Second Battle of Rivas and the Filibuster War, because this was the only time the country fought to remain a sovereign nation. In 1891, on September 15th, a statue of Juan Santamaría was erected in Alajuela to commemorate him, and on many later Independence Day celebrations the government further honored and celebrated Juan Santamaría for his heroism in the struggle against William Walker. Additionally, the anniversary of his death, April 11th, is a national holiday: Juan Santamaría Day.

A popular hero

Coming from humble beginnings and remaining a low level soldier in the national campaign, Juan Santamaría became a hero who represents the everyday people of Costa Rica. Much of the population identifies Santamaría as "one of them", and this distinction is what makes his story resonate with so many people, causing them to support him even more as a national hero.Memorials

On the 15th of September, 1891, the government unveiled the large bronze statue of Juan Santamaría in the park in Alajuela named after the hero. The statue was commissioned by the Costa Rican government and made by the French sculptor Aristide Croisy. Around the base of the statue are images depicting Santamaría volunteering himself to his leader to attempt to burn down the building, and him dying while setting the building alight. Beneath these images sit lion heads, symbolic of strength and courage. At the unveiling of the statue there was a parade in his honor with the President, prominent leadership from the Catholic Church, governors, foreign dignitaries, and the family of other prominent Costa Rican heroes. There were musical performances and speeches emphasizing his heroism and sacrifice, some even comparing him to Christ. Other statues of Juan Santamaría can be found outside the Costa Rican Embassy in Spain, and in front of the Costa Rican National Congress in San José. The coat of arms of Alajuela was changed in 1908 to feature a hand holding a torch, symbolic of Juan Santamaría's heroic act in carrying the torch to burn down the enemy stronghold in theSecond Battle of Rivas

The Second Battle of Rivas occurred on 11 April 1856 between Costa Rican militia under General Mora and the Nicaraguan forces of American mercenary William Walker. The lesser known First Battle of Rivas took place on the 29 June 1855 between ...

.

The international airport for the capital city of Costa Rica, San Jóse, also was named after him.

Anthem

In 1891, Pedro Calderón Navarro and Emilio Pacheco Cooper composed an anthem, ''Himno Patriótico A Juan Santamaría, 11 De Abril'', to Juan Santamaría. It was sung for the first time during the Juan Santamaria Statue inauguration on the 15 of September of 1891. The lyrics are as follows:Cantemos ufanos la egregia memoria de aquel de la patria soldado inmortal, a quien hoy unidas la fama y la historia entonan gozosas un himno triunfal. Cantemos al héroe que en Rivas, pujante, de Marte desprecia el fiero crujir e, intrépido, alzando su tea fulgurante vuela por la patria, sonriendo, a morir. Miradle, en su diestra la tea vengadora agita, y avanza de su hazaña en pos; la muerte, ¿qué importa truene asoladora, si siente en el pecho las iras de un dios? Y avanza y avanza; el plomo homicida lo hiere sin tregua e infúndele ardor, y en tanto que heroico exhala la vida se escucha el incendio rugir vengador. ¡Salud, noble atleta! (3) tu nombre glorioso un pueblo que es libre lo aclama hoy doquier un pueblo que siempre luchó valeroso, pues sabe que es grande, “cual tú”, perecer.

Depictions of Juan Santamaría

Currently, the most widespread depiction of the story of Juan Santamaría is in the play written in 2004 by Jorge Arroyo called ''La tea fulgurante: Juan Santamaría o las iras de un dios'' or in English, ''The Shining Torch: Juan Santamaría and the Wrath of Gods''. This play is approved and promoted by the Costa Rican Ministry of Education, and used in schools throughout the country to teach kids Santamaría's story. The play starts by describing the already widely known story of Juan Santamaría's brave sacrifice of his life for his country. The play then goes back in time to his youth when his dream was to direct the marching band in Alajuela. However, when the Honduran army marched against Costa Rica, Santamaría was intrigued by the soldiers who played instruments, and was inspired to join. The play also includes a description of his single mother, and stories his unknown father that elude to how Santamaría was half black. It explains how Santamaría could read and write, and was also well versed in music which left him disappointed when assigned to play the drums rather than a more complicated instrument. The play describes Juan Santamaría's childhood in the period following theOchomogo War

The Ochomogo War was a civil war fought in Costa Rica, the first in its history, and was fought shortly after the country became independent from Spain.

The most important event was the Battle of Ochomogo (5 April 1823) which was fought on Oc ...

and the brief civil war in Costa Rica, and how Santamaría thought the soldiers who fought were valiant, brave, and honorable. The play, which is an integral part of the national educational curriculum, promotes Santamaría as a brave hero of Costa Rica, and continues to inspire nationalism.Casa de América. “La tea fulgurante. Juan Santamaría o las iras de un dios.” ''YouTube'' video, 20:21. April 12, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qbm8QA4gdm0

Historical Debate

No single or conclusive identity for Juan Santamaría has been agreed upon by scholars and historians, thus the debate over his existence continues to this day. They cite his baptismal certificate, documentation of his name on a list of soldiers from Alajuela, and his mother's pension filing. The first writings about Juan Santamaría were by José de Obaldía and Álvaro Contreras Membreño; in their essays they referred to Santamaría as "glorious" and a "sublime martyr" who gave his life for Costa Rica. Their articles were not written just to tell Santamaría's story, but to unify the population against a threat to their sovereignty. This motivation is important to remember because it influenced how Santamaría was portrayed. Despite being amulatto

(, ) is a racial classification to refer to people of mixed African and European ancestry. Its use is considered outdated and offensive in several languages, including English and Dutch, whereas in languages such as Spanish and Portuguese is ...

, or of mixed race, as his story was popularized, he was significantly white-washed. Even in the famous bronze statue of Santamaría, he looks white and is wearing a French soldier's uniform, further reinforcing the description that he was white. When Santamaría was first glorified, Costa Rican leaders wanted to unify the country as a homogenous and white nation, which caused them to depict Juan Santamaría as white. This misrepresentation caused many historians to question the authenticity of Santamaría as a real person. The municipality of Alajuela, in order to prove Santamaría was real, compiled witnesses and fellow soldiers to attest that he was real, and that he died burning down the enemy stronghold in Rivas. The municipality of Alajuela also provided materials such as his birth certificate, and his mother's request for pension from the government. These documents and statements were all assembled in the book called ''El Libro del Héroe'', or The Book of Hero. Furthermore, Santamaría's baptismal certificate from a church in Alajuela was found, and along with his own name, it also has his mother's name, María Manuela Santamaría. The certificate listed his father's name as unknown, supporting the story that Santamaría was raised by a single mother. Two more documents that historians use to prove his existence can be found in thCosta Rican national archives

These documents are two separate lists of soldiers from Alajuela; the name Juan Santamaría can be seen on both. A document listing the names and causes of death for soldiers in the Costa Rican army, however, is one of the reasons some doubt the story of Juan Santamaría's actions in the Second Battle of Rivas. This document written in 1858 by the chaplain of the Costa Rican army, Priest Rafael Francisco Calvo, listed a man named Juan Santamaría from Alajuela who died from cholera, a common deadly illness at the time. A doctor who lived with Calvo later in his life named Rafael Calderón Muñoz claims when he asked the priest about the man who died of cholera, Calvo claimed it was a different Juan Santamaría than the hero. Other documents brought forward that support Calvo's claim that it was a different Juan Santamaría include a military census listing five different people named Juan Santamaría from Alajuela, and a different report of people who died between April and May of 1856 that listed the death of a Juan Santamaría who died in Rivas. Despite lacking proof of details, there is a strong and consistent oral tradition that Juan Santamaría existed, he was present at the Second Battle of Rivas, he was one of the people who participated in burning down the building, and he died in the act.

Notes

External links

Museo Histórico Juan Santamaría

(Selection of languages, including English) {{DEFAULTSORT:Santamaria, Juan 1831 births 1856 deaths History of Costa Rica People from Alajuela National Heroines and Heroes of Nicaragua National symbols of Costa Rica