Juan Olazábal Ramery on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Juan Olazábal Ramery (1863–1937) was a Spanish Traditionalist politician, first as a

Juan José Tomás Ramón María Melitón Santiago Olazábal Ramery was born to a very distinguished

Juan José Tomás Ramón María Melitón Santiago Olazábal Ramery was born to a very distinguished

In the early 20th century Olazábal emerged as one of key Integrist politicians. His position was ensured as since the death of Ramón Zavala Salazar in 1899 he was heading the party in its national stronghold. Following the death of Ramón Nocedal early 1907, leadership of the Integrist organization, Partido Católico Nacional, was assumed by a triumvirate, though few months later Olazábal became Presidente del Consejo. In 1909 he was elected the official party leader, also nominated honorary president of a number of local Integrist juntas.

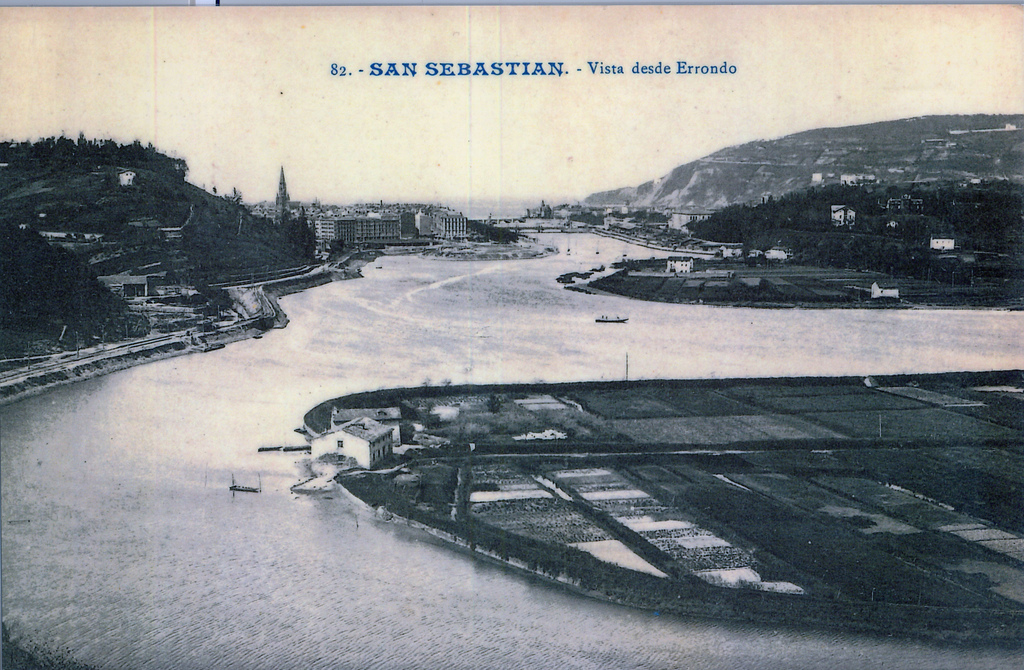

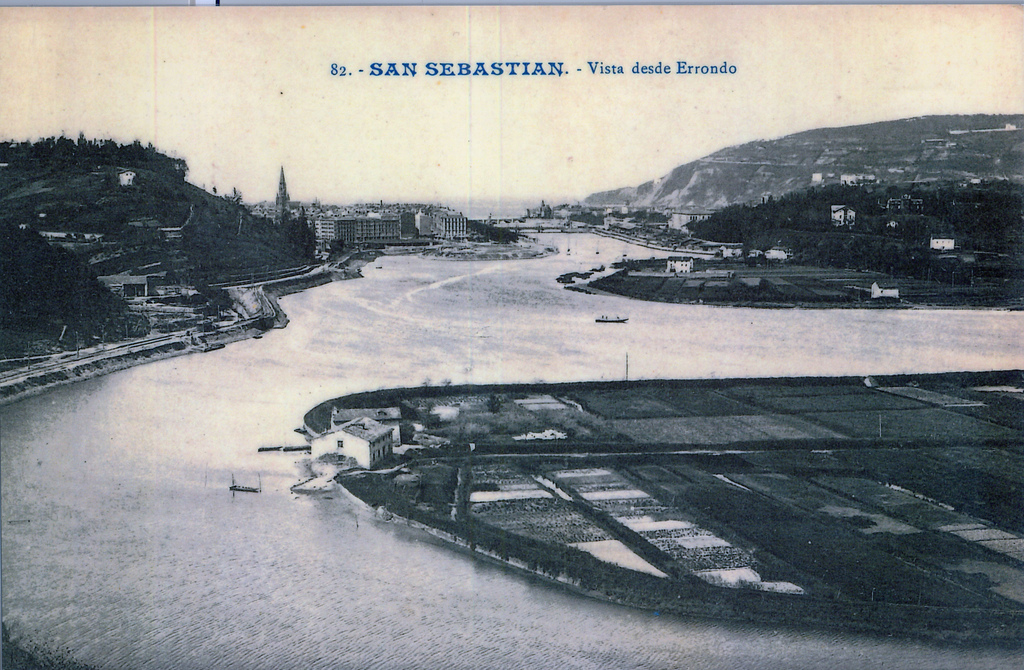

Olazábal's leadership style was rather unobtrusive. Residing in San Sebastian he was away from great national politics; he did not compete for the Cortes and it was minority parliamentarian speaker,

In the early 20th century Olazábal emerged as one of key Integrist politicians. His position was ensured as since the death of Ramón Zavala Salazar in 1899 he was heading the party in its national stronghold. Following the death of Ramón Nocedal early 1907, leadership of the Integrist organization, Partido Católico Nacional, was assumed by a triumvirate, though few months later Olazábal became Presidente del Consejo. In 1909 he was elected the official party leader, also nominated honorary president of a number of local Integrist juntas.

Olazábal's leadership style was rather unobtrusive. Residing in San Sebastian he was away from great national politics; he did not compete for the Cortes and it was minority parliamentarian speaker,  Integrism, conceived by Nocedal as political arm of Spanish Catholicism, has never gained more than lukewarm support of the bishops, alienated by its belligerent intransigence. During the Olazábal leadership things went from bad to worse, as the party was increasingly out of tune with the new Church policy. In the early 20th century the Spanish hierarchy abandoned its traditional strategy of influencing key individuals within the liberal monarchy, and switched to mass mobilisation carried by means of broad popular structures and party politics. The Integrists were reluctant to be one of many Catholic parties, despised the democratic format of policy-making and refused to accept " malmenorismo". Since Olazábal cultivated traditionalist vision of Catholic political engagement, in 1910s and 1920s Partido Católico Nacional was dramatically outpaced by new breed of modern christian-democratic organizations.

Refusing to take part in primoderiverista structures Olazábal focused on ''La Constancia''; his 10-hectare Mundaiz estate became an Integrist shrine. Though Partido Católico Nacional was suspended, its offshoot organizations continued to function. Controlling them was getting increasingly difficult. In 1927 Olazábal expulsed the entire San Sebastian branch of Juventud Integrista, a severe loss given its leader, Ignacio Maria Echaide, launched the Juventud in 1910–1914. In 1930 Integrism re-emerged as Comunión Tradicionalista-Integrista. Still headed by Olazábal it maintained local branches in almost all Spanish provinces and re-affirmed its traditional principles, though with little electoral success.

Integrism, conceived by Nocedal as political arm of Spanish Catholicism, has never gained more than lukewarm support of the bishops, alienated by its belligerent intransigence. During the Olazábal leadership things went from bad to worse, as the party was increasingly out of tune with the new Church policy. In the early 20th century the Spanish hierarchy abandoned its traditional strategy of influencing key individuals within the liberal monarchy, and switched to mass mobilisation carried by means of broad popular structures and party politics. The Integrists were reluctant to be one of many Catholic parties, despised the democratic format of policy-making and refused to accept " malmenorismo". Since Olazábal cultivated traditionalist vision of Catholic political engagement, in 1910s and 1920s Partido Católico Nacional was dramatically outpaced by new breed of modern christian-democratic organizations.

Refusing to take part in primoderiverista structures Olazábal focused on ''La Constancia''; his 10-hectare Mundaiz estate became an Integrist shrine. Though Partido Católico Nacional was suspended, its offshoot organizations continued to function. Controlling them was getting increasingly difficult. In 1927 Olazábal expulsed the entire San Sebastian branch of Juventud Integrista, a severe loss given its leader, Ignacio Maria Echaide, launched the Juventud in 1910–1914. In 1930 Integrism re-emerged as Comunión Tradicionalista-Integrista. Still headed by Olazábal it maintained local branches in almost all Spanish provinces and re-affirmed its traditional principles, though with little electoral success.

Militant republican secularism was acknowledged by the Integrists as a barbarian onslaught against the very foundations of civilisation. Overwhelmed be the Leftist sway, Olazábal realized that his party stood little chance of surviving on its own. The row between traditionalist Integrism and modern

Militant republican secularism was acknowledged by the Integrists as a barbarian onslaught against the very foundations of civilisation. Overwhelmed be the Leftist sway, Olazábal realized that his party stood little chance of surviving on its own. The row between traditionalist Integrism and modern  It is not clear whether Olazábal was engaged in Carlist preparations to rebellion and whether he was even aware of the forthcoming insurgency. Following the outbreak of hostilities he remained in San Sebastian, where the coup failed, and went on editing ''La Constancia''. He was detained on one of the ships anchored in San Sebastian and later moved to the Bilbao Angeles Custodios prison. Since the Basque government did not deploy autonomous police to protect the building during the unrest, caused by the nationalist bombing raid over the city, the prison was entrusted to the UGT militia unit. On January 4 the socialist militiamen executed around 100 prisoners; some were killed by hand grenades thrown into the cells, some were shot and some were reportedly slashed with machetes. It is not clear how exactly Juan Olazábal died.detailed accounts differ; Pedro Barruso Barés, ''La represión en las zonas republicana y franquista del País Vasco durante la Guerra Civil'', n:''Historia Contemporánea'' 35 (2007), pp. 653-681 identifies the perpetrators as "incontrolados" militants of CNT and UGT, while the anarchists denied any responsibility, see their account ''La manipulación de la Memoria Histórica'', n:''CNT Gipuzkoa'', availabl

It is not clear whether Olazábal was engaged in Carlist preparations to rebellion and whether he was even aware of the forthcoming insurgency. Following the outbreak of hostilities he remained in San Sebastian, where the coup failed, and went on editing ''La Constancia''. He was detained on one of the ships anchored in San Sebastian and later moved to the Bilbao Angeles Custodios prison. Since the Basque government did not deploy autonomous police to protect the building during the unrest, caused by the nationalist bombing raid over the city, the prison was entrusted to the UGT militia unit. On January 4 the socialist militiamen executed around 100 prisoners; some were killed by hand grenades thrown into the cells, some were shot and some were reportedly slashed with machetes. It is not clear how exactly Juan Olazábal died.detailed accounts differ; Pedro Barruso Barés, ''La represión en las zonas republicana y franquista del País Vasco durante la Guerra Civil'', n:''Historia Contemporánea'' 35 (2007), pp. 653-681 identifies the perpetrators as "incontrolados" militants of CNT and UGT, while the anarchists denied any responsibility, see their account ''La manipulación de la Memoria Histórica'', n:''CNT Gipuzkoa'', availabl

here

Juan Olazábal on euskomedia

Estella Statute text

Liga Foral declaration

Historical Index of Deputies 1899

virtual visit at a former Olazábal Mundaiz estate

Catholic college at former Olazábal Mundaiz estate

*

Errekete (Euskara)

''Vizcainos! Por Dios y por España''; contemporary Carlist propaganda

{{DEFAULTSORT:Olazabal Ramery, Juan 1863 births 1937 deaths Corporatism 19th century in the Basque Country Basque prisoners and detainees Carlists Integralism Leaders of political parties in Spain Members of the Congress of Deputies (Spain) People from Irun Popular Action (Spain) politicians Regionalism (politics) Spanish casualties of the Spanish Civil War Spanish anti-communists 19th-century Spanish lawyers Spanish monarchists Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War (National faction) Spanish prisoners and detainees Spanish Roman Catholics Spanish victims of crime Basque journalists Complutense University of Madrid alumni

Carlist

Carlism (; ; ; ) is a Traditionalism (Spain), Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty, one descended from Infante Carlos María Isidro of Spain, Don Carlos, ...

, then as an Integrist, and eventually back in the Carlist ranks. In 1899-1901 he served in the Cortes

Cortes, Cortés, Cortês, Corts, or Cortès may refer to:

People

* Cortes (surname), including a list of people with the name

** Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), a Spanish conquistador

Places

* Cortes, Navarre, a village in the South border of ...

, and in 1911-1914 he was a member of the Gipuzkoa

Gipuzkoa ( , ; ; ) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the autonomous community of the Basque Country. Its capital city is Donostia-San Sebastián. Gipuzkoa shares borders with the French department of Pyrénées-Atlantiqu ...

n diputación provincial. Between 1897 and 1936 he managed and edited the San Sebastián

San Sebastián, officially known by the bilingual name Donostia / San Sebastián (, ), is a city and municipality located in the Basque Autonomous Community, Spain. It lies on the coast of the Bay of Biscay, from the France–Spain border ...

daily ''La Constancia

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second most populous city in the United States of America.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

*La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

*"L.A.", a song by Elliott Smit ...

''. He is best known as the nationwide leader of Integrism, the grouping he led between 1907 and 1931.

Family and youth

Juan José Tomás Ramón María Melitón Santiago Olazábal Ramery was born to a very distinguished

Juan José Tomás Ramón María Melitón Santiago Olazábal Ramery was born to a very distinguished Gipuzkoa

Gipuzkoa ( , ; ; ) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the autonomous community of the Basque Country. Its capital city is Donostia-San Sebastián. Gipuzkoa shares borders with the French department of Pyrénées-Atlantiqu ...

n dynasty, much branched and intermarried with a number of other well known local families. His father, Juan Antonio Olazábal Arteaga, held a number of estates in Eastern part of the province. Following his early death in 1867, Juan and his siblings were raised by their mother, Prudencia Ramery Zuzuarregui. At the outbreak of the Third Carlist War

The Third Carlist War (), which occurred from 1872 to 1876, was the last Carlist War in Spain. It is sometimes referred to as the "Second Carlist War", as the earlier Second Carlist War, "Second" War (1847–1849) was smaller in scale and relative ...

the family sought refuge in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. Following their return to Spain Juan was educated in the Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

college in Orduña, where he met and befriended Sabino Arana

Sabino Policarpo Arana Goiri (in Spanish language, Spanish), Sabin Polikarpo Arana Goiri (in Basque language, Basque), or Arana ta Goiri'taŕ Sabin (self-styled) (26 January 1865 – 25 November 1903), was a spaniards, Spanish writer and the ...

, to proceed with law studies in another Jesuit institute, Colegio del Pasaxe in the Galician A Guarda

A Guarda is a municipality in the province of Pontevedra in the autonomous community of Galicia, in Spain. It is situated in the ''comarca'' of O Baixo Miño.

Demography

Colors=

id:lightgrey value:gray(0.9)

id:darkgrey value:gray(0.7) ...

. He then moved to Universidad Central in Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

, to graduate in 1885.

Though the family in some sources is described as Carlist, in fact its different branches adhered to different political options. Juan's paternal uncle, Ramón Olazábal Arteaga Ramón or Ramon may refer to:

People Given name

*Ramón (footballer, born 1950), Brazilian footballer

* Ramón (footballer, born 1983), Brazilian footballer

* Ramón (footballer, born 1988), Brazilian footballer

*Ramón (footballer, born 1990), Br ...

, as coronel

Coronel may refer to:

* Archaic and Spanish variant of colonel

* Coronel, Chile, a port city in Chile

* Battle of Coronel off the Chilean coast during World War I

* The World War II German auxiliary cruiser HSK ''Coronel'', see German night fight ...

of miqueletes sided with the Isabelinos during the Third Carlist War, growing to the commander of the entire formation and also the civil governor of Irun. On the other hand, Juan's maternal uncle, Liborio Ramery Zuzuarregui, made his name as a Carlist politician, Gipzukoan deputy to the Cortes

Cortes, Cortés, Cortês, Corts, or Cortès may refer to:

People

* Cortes (surname), including a list of people with the name

** Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), a Spanish conquistador

Places

* Cortes, Navarre, a village in the South border of ...

and a Traditionalist writer. A distant relative from a paternal branch, Tirso de Olazábal y Lardizábal Tirso is Spanish and Portuguese for Thyrsus, and usually refers to the saint of that name ( Saint Thyrsus) (San Tirso, Santo Tirso). It can also refer to:

People

* Tirso Cruz III (born 1952), Filipino actor

* Tirso de Molina (1579-1648), Spani ...

, became head of Gipuzkoan Carlism and one of the national party leaders. It was rather the influence of Juan's maternal family, especially Liborio, which combined with the Jesuit education formed him as a Carlist. Juan Olazábal has never married and had no children. Some members of the Olazábal family were active as Carlist politicians in the early Francoist era, though they were very distant Juan's relatives.

Early career

Already as a student Olazábal engaged in public activity taking part in Carlist-sponsored Catholic initiatives, e.g. protests againstkrausism

Krausism is a doctrine named after the German philosopher Karl Christian Friedrich Krause (1781–1832) that advocates doctrinal tolerance and academic freedom from dogma.

One of the philosophers of identity, Krause endeavoured to reconcile ...

-flavored heterodoxy in education or against promotion of figures like Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno ( , ; ; born Filippo Bruno; January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, poet, alchemist, astrologer, cosmological theorist, and esotericist. He is known for his cosmological theories, which concep ...

; instead, he advocated Catholic orthodoxy as fundament of public education in Spain. In 1888 both Olazábal Ramery brothers, Juan and Javier, defected from mainstream Carlism and joined its breakaway branch led by Ramón Nocedal, known as Integrism

In politics, integralism, integrationism or integrism () is an interpretation of Catholic social teaching that argues the principle that the Catholic faith should be the basis of public law and public policy within civil society, wherever the ...

; they followed the example of their uncle Liborio, who entered the Integrist executive as secretario of junta central. In 1889 they were already active in various minor Integrist public initiatives. Juan returned to Gipuzkoa, building the party structures and mobilising its popular support in the province, which soon turned out to be a national Integrist stronghold. In the 1891 elections the party gained 2 mandates in the province, one conquered by Juan's uncle Liborio and one by the party leader Nocedal. Since at that time Integrism and mainstream Carlism competed with vehement hostility, the latter success looked triumphant: Nocedal defeated the Gipuzkoan mainstream Carlist leader, Tirso Olazábal. Nocedal was also re-elected in the subsequent elections of 1893.

Following the death of Liborio Ramery in 1894, Juan Olazábal took his place in provincial party leadership. The same year he was already representing the province at national party gatherings, hosting party meetings at his Mundaiz estate in 1895 and formally growing to segundo adjunto of the Gipuzkoan branch in 1896. He was engaged in negotiations with other parties during local electoral campaigns. An alliance with the conservatives, known as Union Vasconavarra, produced 3 Integrist mandates into the San Sebastian ayuntamiento

''Ayuntamiento'' ()In other languages of Spain:

* ().

* ().

* (). is the general term for the town council, or ''cabildo'', of a municipality or, sometimes, as is often the case in Spain and Latin America, for the municipality itself. is mai ...

in 1893; the same coalition produced the same outcome in 1895, this time Olazábal elected as concejal. He made himself renowned for defending traditional local establishments against the centralising and modernising designs of the Madrid government. In 1896 he was forced to resign after a failed attempt to block ministerial legislation he considered detrimental to the interests of the city, but was reinstated following a successful appeal and served until 1899.

''La Constancia''

In the late 1890s the Gipuzkoan Integrism underwent a major crisis, though its nature remains disputed. One theory highlights the alliance strategy; Nocedal changed his recommendations, suggesting coalitions with parties offering the best deal instead of the most approximate ones. Another theory attributes the conflict to nationalist penchant of the dissenters. As they refused to step in line, the rebels, headed byPedro Grijalba

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for ''Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, meaning ...

, Ignacio Lardizábal and Aniceto de Rezola, were expulsed by the provincial Junta. Since the outcasts controlled a provincial Gipuzkoan Integrist daily ''El Fuerista'', Olazábal was asked to compensate for the loss; in 1897 he set up a new party newspaper, the San Sebastian-based ''La Constancia

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second most populous city in the United States of America.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

*La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

*"L.A.", a song by Elliott Smit ...

''; initially it appeared with a sub-title ''Diario Integro Fuerista'', later changed to ''Diario Integrista'', ''Diario Integro-Tradicionalista'' and finally, ''Diario Tradicionalista''. His personal property, it was published until 1936 and, apart from being an official paper of Gipuzkoan Integrism for 34 years, until the end it remained sort of Olazábal's personal political and ideological tribune.

Named after a Nocedalist daily of 1867–68, ''La Constancia'' was one of 4 dailies published in Gipuzkoa and one of 14 periodicals controlled by the Integrists in Spain.

It remained a modest enterprise, with 2 journalists and 3 permanent collaborators. Its circulation remained unimpressive; in 1920 it was 1,650 copies, compared to 12,000 of the leading Gipuzkoan dailies, ''La Voz de Gipuzkoa'' and ''El Pueblo Vasco'', though still above this of an Integrist daily from neighboring Navarre, which went out of print in some 850-1000 copies. Given a semi-private nature of the paper, there is little doubt its longevity was sustained financially by industrial tycoons of Integrist sympathies. Over the years it gradually became an icon of Traditionalist Spanish press. ''La Constancia'' combined traditionalist Catholic ultraconservatism launched as Integrism by Nocedal with the defence of local Gipuzkoan identity and loyalty. During the Republican years it was subject to suspensions and other administrative measures. In the early 1930s it was integrated into the modern Carlist propaganda machinery and Olazabal ceded its directorship to Francisco Juaristi:; since 1934 it included one page in Basque. After the outbreak of the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

its premises were seized by the Republican militias. Once the Carlists conquered San Sebastian its linotype machine

The Linotype machine ( ) is a "line casting" machine used in printing which is manufactured and sold by the former Mergenthaler Linotype Company and related It was a hot metal typesetting system that cast lines of metal type for one-time use. Li ...

s were used to launch ''La Voz de Espańa'', which employed also some of the ''La Constancia's'' editorial staff.

Deputy

In the last years of the 19th century venomous hostility between Integrists and mainstream Carlists gave way to rapprochement, commenced in Gipuzkoa. Its result was a provincial electoral alliance. InAzpeitia

Azpeitia (meaning 'down the rock' in Basque language, Basque) is a town and Municipalities of Spain, municipality within the Provinces of Spain, province of Gipuzkoa, in the Basque Country (autonomous community), Basque Country, Spain, located on ...

, where two branches of Traditionalism used to compete, the Carlist candidate Teodoro Arana Belaustegui was withdrawn in favour of the Integrists. Their candidate turned out to be Olazábal, elected also by Carlist votes to the Cortes. The years of 1899-1901 were his only term in the parliament; during the successive elections the Azpeitia mandate – virtually ensured for the party – was claimed by other Integrist politicians.

For reasons which remain rather unclear in the early 20th century Olazábal abandoned national politics and dedicated himself to the local Gipuzkoan issues. In 1904-1906 he engaged in a broad coalition named Liga Foral Autonomista de Guipúzcoa and became its second vicepresident. The alliance declared itself dedicated to traditional provincial fueros

(), (), (), () or () is a Spanish legal term and concept. The word comes from Latin , an open space used as a market, tribunal and meeting place. The same Latin root is the origin of the French terms and , and the Portuguese terms and ...

and identified fiscal and administrative autonomy as its goals. Its immediate objective was negotiating a new Concierto económico with Madrid and indeed, a contemporary scholar considers the grouping simply a vehicle for pursuing economic goals of local industry tycoons.

Broad and loose political rapprochement of Gipuzkoan parties pursuing regionalist goals produced Olazábal's success in elections to Diputación Provincial in 1907 and 1911, in 1914 serving as member of its Comisión Provincial. He is noted not only for work promoting traditional local legal establishments, but also for efforts to sustain typical Gipuzkoan agriculture, like protecting Pyrenaic cattle breeds by means of introducing herdbook

A breed registry, also known as a herdbook, studbook or register, in animal husbandry, the hobby of animal fancy, is an official list of animals within a specific breed whose parents are known. Animals are usually registered by their breeders wh ...

s, supporting the Fraisoro agronomy school and supervising provincial veterinary services. Though lacking technical knowledge and somewhat incapacitated by a framework of political alliances, he nevertheless tried to promote the experts against incompetence of the politicians.

''Jefe''

In the early 20th century Olazábal emerged as one of key Integrist politicians. His position was ensured as since the death of Ramón Zavala Salazar in 1899 he was heading the party in its national stronghold. Following the death of Ramón Nocedal early 1907, leadership of the Integrist organization, Partido Católico Nacional, was assumed by a triumvirate, though few months later Olazábal became Presidente del Consejo. In 1909 he was elected the official party leader, also nominated honorary president of a number of local Integrist juntas.

Olazábal's leadership style was rather unobtrusive. Residing in San Sebastian he was away from great national politics; he did not compete for the Cortes and it was minority parliamentarian speaker,

In the early 20th century Olazábal emerged as one of key Integrist politicians. His position was ensured as since the death of Ramón Zavala Salazar in 1899 he was heading the party in its national stronghold. Following the death of Ramón Nocedal early 1907, leadership of the Integrist organization, Partido Católico Nacional, was assumed by a triumvirate, though few months later Olazábal became Presidente del Consejo. In 1909 he was elected the official party leader, also nominated honorary president of a number of local Integrist juntas.

Olazábal's leadership style was rather unobtrusive. Residing in San Sebastian he was away from great national politics; he did not compete for the Cortes and it was minority parliamentarian speaker, Manuel Senante

Manuel Senante Martínez (1873–1959) was a Spanish Traditionalism (Spain), Traditionalist politician and publisher, until 1931 adhering to the Integrism (Spain), Integrist current and afterwards active in the Carlist ranks. He is known mostly ...

, acting as party representative in Madrid. Though formally the owner of national Integrist daily, '' El Siglo Futuro'', he left Senante to manage the newspaper and seldom contributed as an author, concentrating rather on ''La Constancia''. Finally, during political negotiations with other parties, he authorised the others to represent Partido Católico Nacional.

In terms of political course Olazábal followed Nocedal closely. The fundamental assumption was that all public activity should be guided by Catholic principles and executed in line with the Roman Catholic teaching. In day-to-day activities it boiled down to opposing secularisation

In sociology, secularization () is a multilayered concept that generally denotes "a transition from a religious to a more worldly level." There are many types of secularization and most do not lead to atheism or irreligion, nor are they automatica ...

and defending the Church, as demonstrated during Ley de Candado crisis. Secondary threads were promoting traditional regional establishments and fighting democracy, especially parties combining nationalism and socialism. Towards the monarchy Integrism remained ambiguous, with some sections of the party favoring different dynastical visions and some leaning towards accidentalism, prepared to accept a republican project.

Integrism, conceived by Nocedal as political arm of Spanish Catholicism, has never gained more than lukewarm support of the bishops, alienated by its belligerent intransigence. During the Olazábal leadership things went from bad to worse, as the party was increasingly out of tune with the new Church policy. In the early 20th century the Spanish hierarchy abandoned its traditional strategy of influencing key individuals within the liberal monarchy, and switched to mass mobilisation carried by means of broad popular structures and party politics. The Integrists were reluctant to be one of many Catholic parties, despised the democratic format of policy-making and refused to accept " malmenorismo". Since Olazábal cultivated traditionalist vision of Catholic political engagement, in 1910s and 1920s Partido Católico Nacional was dramatically outpaced by new breed of modern christian-democratic organizations.

Refusing to take part in primoderiverista structures Olazábal focused on ''La Constancia''; his 10-hectare Mundaiz estate became an Integrist shrine. Though Partido Católico Nacional was suspended, its offshoot organizations continued to function. Controlling them was getting increasingly difficult. In 1927 Olazábal expulsed the entire San Sebastian branch of Juventud Integrista, a severe loss given its leader, Ignacio Maria Echaide, launched the Juventud in 1910–1914. In 1930 Integrism re-emerged as Comunión Tradicionalista-Integrista. Still headed by Olazábal it maintained local branches in almost all Spanish provinces and re-affirmed its traditional principles, though with little electoral success.

Integrism, conceived by Nocedal as political arm of Spanish Catholicism, has never gained more than lukewarm support of the bishops, alienated by its belligerent intransigence. During the Olazábal leadership things went from bad to worse, as the party was increasingly out of tune with the new Church policy. In the early 20th century the Spanish hierarchy abandoned its traditional strategy of influencing key individuals within the liberal monarchy, and switched to mass mobilisation carried by means of broad popular structures and party politics. The Integrists were reluctant to be one of many Catholic parties, despised the democratic format of policy-making and refused to accept " malmenorismo". Since Olazábal cultivated traditionalist vision of Catholic political engagement, in 1910s and 1920s Partido Católico Nacional was dramatically outpaced by new breed of modern christian-democratic organizations.

Refusing to take part in primoderiverista structures Olazábal focused on ''La Constancia''; his 10-hectare Mundaiz estate became an Integrist shrine. Though Partido Católico Nacional was suspended, its offshoot organizations continued to function. Controlling them was getting increasingly difficult. In 1927 Olazábal expulsed the entire San Sebastian branch of Juventud Integrista, a severe loss given its leader, Ignacio Maria Echaide, launched the Juventud in 1910–1914. In 1930 Integrism re-emerged as Comunión Tradicionalista-Integrista. Still headed by Olazábal it maintained local branches in almost all Spanish provinces and re-affirmed its traditional principles, though with little electoral success.

Republic and war

Militant republican secularism was acknowledged by the Integrists as a barbarian onslaught against the very foundations of civilisation. Overwhelmed be the Leftist sway, Olazábal realized that his party stood little chance of surviving on its own. The row between traditionalist Integrism and modern

Militant republican secularism was acknowledged by the Integrists as a barbarian onslaught against the very foundations of civilisation. Overwhelmed be the Leftist sway, Olazábal realized that his party stood little chance of surviving on its own. The row between traditionalist Integrism and modern christian-democratic

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo-scholasticism, as well a ...

groupings was already too wide and very few in the party considered rapprochement. On the other hand, ultraconservative vision of religion was shared by mainstream Carlists; as a result, Integristas rather unanimously decided to swallow their accidentalism. Following 44 years of separate political existence Olazábal led them to 1932 reunification within Carlism, into the party named Comunión Tradicionalista

The Traditionalist Communion (, CT; , ) was one of the names adopted by the Carlist movement as a political force since 1869.

History

In October 1931, Carlist claimant to the Spanish throne Duke Jaime died. He was succeeded by the 82-year-old ...

. Though formally the provincial party leader was Bernardo Elío y Elío

Bernardo Elío y Elío, 7th Marquess of Las Hormazas (1867–1937), was a Spanish people, Spanish aristocrat and politician. He supported the Carlism, Carlist cause. During the late Restoration (Spain), Restoration period he formed part of the re ...

, in fact Olazábal formed a local ruling duumvirate

Diarchy (from Greek , ''di-'', "double", and , ''-arkhía'', "ruled"),Occasionally spelled ''dyarchy'', as in the ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' article on the colonial British institution duarchy, or duumvirate. is a form of government charact ...

.

Within consolidated Carlism the former Integrists remained a very influential group. By means of a new publishing house, Editorial Tradicionalista, they continued to control ''El Siglo Futuro'', which became a semi-official Carlist daily. Many former Integros, like a Cantabrian Jose Luis Zamanillo, Castillano José Lamamie, Alicantino Manuel Senante or Andalusian Manuel Fal assumed top positions within the party. Olazábal, due to his age hardly involved in day-to-day business, became sort of a mentor and moral authority. The visible Integrist impact on Comunión Tradicionalista triggered some grumblings among Carlists, especially among the Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

se.

Olazábal kept lambasting secular republicanism, which cost ''El Siglo Futuro'' and ''La Constancia'' periodical administrative suspensions (the first one in August 1931) and Olazábal himself a police detention; he spent three days in jail. Always championing local traditional establishments, he was profoundly disappointed by turn of the Basque cause. He denounced the initial autonomy draft as godless, considering also the Estella Statute version anti-religious and anti-fuerist. Within the united Carlist community he and Victor Pradera led the anti-statute group, as opposed to the pro-statute Carlists represented by José Luis Oriol, Marcelino Oreja and Joaquín Beunza. The divided Carlists refrained from taking a clear political stance, which eventually contributed to failure of the autonomy project.

here

See also

*Ramón Nocedal Romea

Ramón Nocedal Romea (1842–1907) was a Spanish Catholic ultraconservative politician, first member of the Neocatólicos, then of the Carlists, and finally of the Integrists. He is known as leader of a political current known as Integrismo (18 ...

* Manuel Senante Martinez

Footnotes

Further reading

* Cristina Barreiro Gordillo, ''El carlismo y su red de prensa en la Segunda República'', Madrid 2003, * Pedro Berriochoa Azcárate, ''1911: Incompatibilidades burocráticas sobre fondo caciquil en la Diputación de Gipuzkoa, n:''Historia Contemporánea'' 40 (2010), pp. 29-65 * Martin Blinkhorn, ''Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939'', Cambridge 1975, * Luis Castells, ''Fueros y conciertos económicos. La Liga Foral Autonomista de Gipúzcoa (1904-1906)''. San Sebastián, 1980, * Antonio Cillán Apalategui, ''Elecciones a diputados provinciales en Guipuzcoa el año 1911'', n:''Historia'' 22 (1977), pp. 121-127 * Idioia Estornés Zubizarreta, ''La construction de una nacionalidad Vasca. El Autonomismo de Eusko-Ikaskuntza (1918-1931)'', Donostia 1990 * María Obieta Vilallonga, ''Los integristas guipuzcoanos. Desarrollo y organización del Partido Católico Nacional en Guipúzcoa (1888-1898)'', Bilbao 1996, , 9788470863264External links

Juan Olazábal on euskomedia

Estella Statute text

Liga Foral declaration

Historical Index of Deputies 1899

virtual visit at a former Olazábal Mundaiz estate

Catholic college at former Olazábal Mundaiz estate

*

Errekete (Euskara)

''Vizcainos! Por Dios y por España''; contemporary Carlist propaganda

{{DEFAULTSORT:Olazabal Ramery, Juan 1863 births 1937 deaths Corporatism 19th century in the Basque Country Basque prisoners and detainees Carlists Integralism Leaders of political parties in Spain Members of the Congress of Deputies (Spain) People from Irun Popular Action (Spain) politicians Regionalism (politics) Spanish casualties of the Spanish Civil War Spanish anti-communists 19th-century Spanish lawyers Spanish monarchists Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War (National faction) Spanish prisoners and detainees Spanish Roman Catholics Spanish victims of crime Basque journalists Complutense University of Madrid alumni