Joseph Rayner Stephens on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

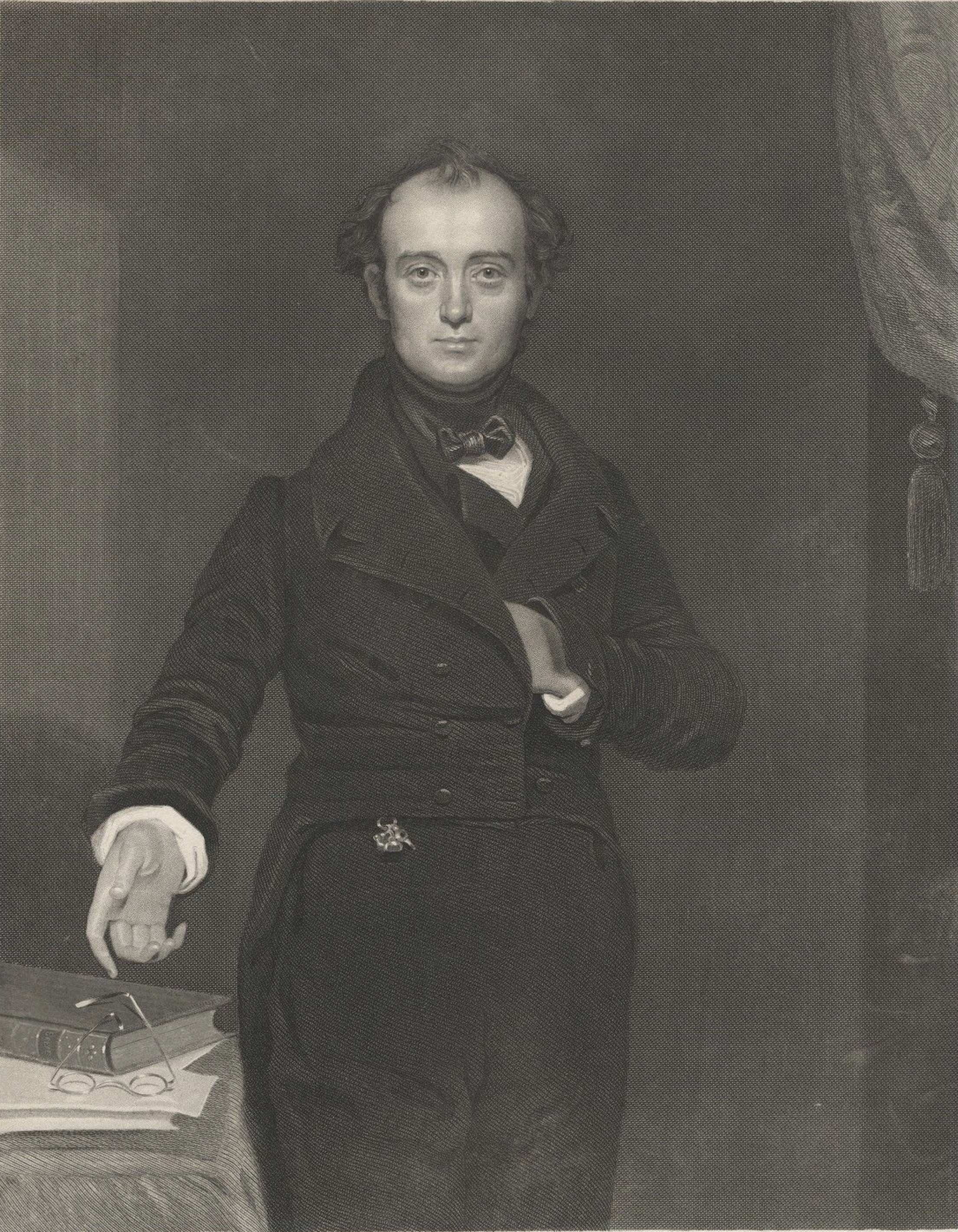

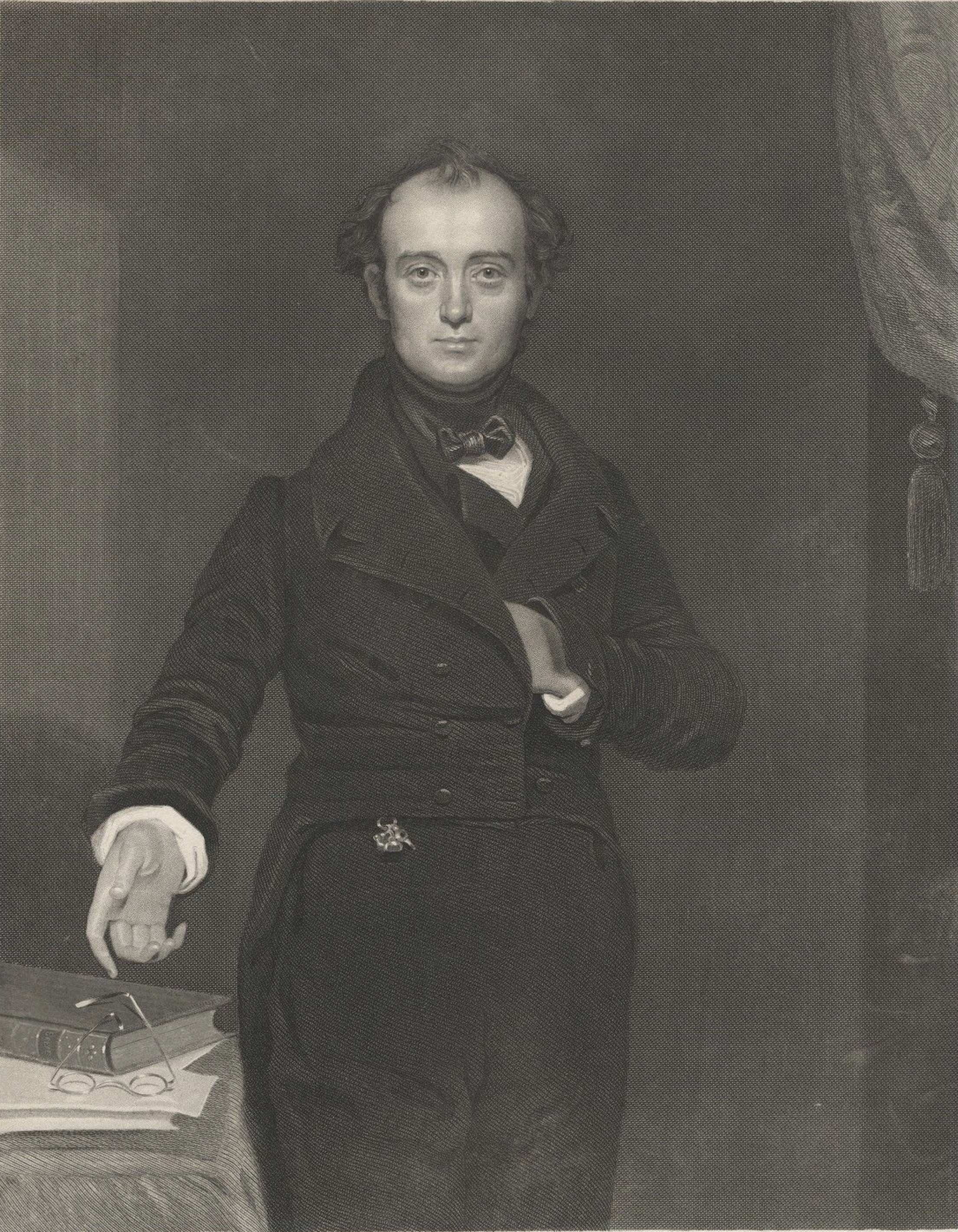

Joseph Rayner Stephens (8 March 1805 – 18 February 1879) was a

Joseph Rayner Stephens (8 March 1805 – 18 February 1879) was a

He became active in the movement for

He became active in the movement for

Heavy sureties had to be given for his good behaviour for the next five years, and he did not resume public speaking until participating in a campaign for better enforcement of the Ten Hours' Act (i.e. against the relay system) in 1849., explicitly holding non-compliance and non-enforcement to be responsible for social unrest and the more extreme forms that manifested itself in: "It is the practice of injustice towards the poor which estranges them from the institutions of their country, and leads them into many wild and unreasoning projects to obtain deliverance from the intolerable yoke that has been fastened upon them" He supported opposition to the 'Compromise Act' of 1850 and took part in abortive campaigns for legislation for a true ten-hour day enforced by stoppage of machinery. In 1857, he looked back on his agitational heyday

Heavy sureties had to be given for his good behaviour for the next five years, and he did not resume public speaking until participating in a campaign for better enforcement of the Ten Hours' Act (i.e. against the relay system) in 1849., explicitly holding non-compliance and non-enforcement to be responsible for social unrest and the more extreme forms that manifested itself in: "It is the practice of injustice towards the poor which estranges them from the institutions of their country, and leads them into many wild and unreasoning projects to obtain deliverance from the intolerable yoke that has been fastened upon them" He supported opposition to the 'Compromise Act' of 1850 and took part in abortive campaigns for legislation for a true ten-hour day enforced by stoppage of machinery. In 1857, he looked back on his agitational heyday

Holyoake, George Jacob. (1881) ''Life of Joseph Rayner Stephens, preacher and political orator''. London: Williams and Norgate

:Issued to support the memorial appeal. Not so much a 'Life' as a collection of extensive quotations from a few letters and sermons - furthermore Holyoake (a Radical and free-thinker) is clearly not in sympathy with Stephens' political position (and perhaps does not understand it) Edwards, M.S. (1994). ''Purge This Realm – A Life of Joseph Rayner Stephens''. London: Epworth Press.

Spartacus article on Joseph Rayner Stephens

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stephens, Joseph Rayner 1805 births 1879 deaths British Methodists Clergy from Edinburgh Burials in Greater Manchester

Joseph Rayner Stephens (8 March 1805 – 18 February 1879) was a

Joseph Rayner Stephens (8 March 1805 – 18 February 1879) was a Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

minister who offended the Wesleyan Conference by his support for separating the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

from the State. Resigning from the Wesleyan Connection, he became free to campaign for factory reform, and against the New Poor Law. He became associated with 'physical force' Chartism (although he later denied he had ever been a Chartist) and spent eighteen months in jail for his presence at an unlawful assembly and his use there of seditious language.

Born in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

in 1805, he moved to Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

when his minister father was posted there in 1819. During his religious career, he worked in a variety of places (including Stockholm

Stockholm () is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, largest city of Sweden as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people liv ...

and Newcastle-upon-Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is als ...

) before arriving in Ashton-under-Lyne

Ashton-under-Lyne is a market town in Tameside, Greater Manchester, England. The population was 45,198 at the 2011 census. Historically in Lancashire, it is on the north bank of the River Tame, in the foothills of the Pennines, east of Manche ...

in 1832. He was the brother of the philologist George Stephens George Stephens may refer to:

*George Stephens (playwright) (1800–1851), English author and dramatist

*George Stephens (philologist) (1813–1895), British archaeologist and philologist, who worked in Scandinavia

* George Washington Stephens, Sr. ...

.; three of his other brothers (John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

and Samuel

Samuel ''Šəmūʾēl'', Tiberian: ''Šămūʾēl''; ar, شموئيل or صموئيل '; el, Σαμουήλ ''Samouḗl''; la, Samūēl is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the bibl ...

) emigrated to Southern Australia

The term Southern Australia is generally considered to refer to the states and territories of Australia of New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and South Australia. The part of Western Australia south of lati ...

and played their parts in the early years of that colony.

Leaves Wesleyan Methodism

Stephens gave a number of talks in favour of disestablishment and became secretary of the Ashton branch of a society arguing for disestablishment. His district conference attempted to discipline him for engaging in controversial political activity, and for taking a view on Church Establishment contrary to that of Wesleyans and ofJohn Wesley

John Wesley (; 2 March 1791) was an English people, English cleric, Christian theology, theologian, and Evangelism, evangelist who was a leader of a Christian revival, revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The soci ...

. Stephens was willing to accept a temporary suspension on most points, but not on deviation from the views of Wesley, in whose writings he found views matching his own. The national conference nonetheless asserted that true Wesleyans were in favour of the existence of an Established Church and lengthened his suspension: Stephens resigned and set up his own "Stephenite" churches in Ashton-under-Lyne

Ashton-under-Lyne is a market town in Tameside, Greater Manchester, England. The population was 45,198 at the 2011 census. Historically in Lancashire, it is on the north bank of the River Tame, in the foothills of the Pennines, east of Manche ...

and Stalybridge

Stalybridge () is a town in Tameside, Greater Manchester, England, with a population of 23,731 at the 2011 Census.

Historic counties of England, Historically divided between Cheshire and Lancashire, it is east of Manchester city centre and no ...

.

Political agitation

factory reform

The Factory Acts were a series of acts passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom to regulate the conditions of industrial employment.

The early Acts concentrated on regulating the hours of work and moral welfare of young children employed ...

and in the anti-Poor Law movement. In both sermons and speeches he denounced the practices of millowners and the intentions of the new Poor Law as un-Christian and hence doomed to end in social upheaval and bloodshed. Like Richard Oastler

Richard Oastler (20 December 1789 – 22 August 1861) was a "Tory radical", an active opponent of Catholic Emancipation and Parliamentary Reform and a lifelong admirer of the Duke of Wellington; but also an abolitionist and prominent in the ...

he held Tory views on most issues; like Oastler he advised his followers that it was legal to arm themselves and that governmenment would pay more attention to their views if they did. He and Oastler (who saw the younger man as his natural successor) became associated with the Chartists

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, w ...

, who also saw the new Poor Law, the rapacity and inhumanity of employers and the poverty of workers as issues requiring urgent attention, but sought to remedy them by fundamental political change. Whereas Oastler openly opposed the constitutional aspirations of the Chartists, and did not become involved in Chartism, Stephens addressed Chartist meetings and was elected a delegate to the National Conference. However, as he later told his congregation, he was never a Radical, let alone a 'five-point man' : "I would rather walk to London on my bare knees, on sharp flint stones to attend an Anti-poor Law meeting, than be carried to London in a coach and six, pillowed with down to present that petition - the "national petition" to the House of Commons" Nor did his advice to followers to arm themselves indicate any support for 'physical force' Chartism or the overthrow of the existing order by violence or by general strike: "My friends, never put your trust in, and never follow after, men who pretend to be able to manufacture a revolution. A revolution, a rolling away of the whole from evil to good, from wrong to right, from injustice and oppression to righteousness and equal rule, never yet was manufactured, and never will be manufactured. God, who teaches you what your rights are, what the blessings He has endowed you withal, will, in his own good time, if that time should come - God will teach your hands to war, and your fingers to fight"

Imprisonment

In December 1838, Stephens was arrested, charged with having participated in a tumultuous assembly at Leigh on 13 November 1838 and having incited the meeting to violence against inhabitants of the neighbourhood. A Lancashire grand jury returned a true bill both for the Leigh meeting and for sermons preached in Ashton-under-Lyne: however Stephens was eventually tried at Chester in connection with a meeting at Hyde (then in Cheshire) on 14 November 1838. Stephens was charged with attending "an unlawful meeting , seditiously and tumultuously met together by torch-light, and with fire-arms disturbing the public peace" and two counts of speaking at the meeting. Witnesses said attendance at the meeting had been about 5,000 mostly from outside Hyde, firearms had been discharged, banners with slogans such as "Tyrants, believe, and tremble" and "BLOOD" had been displayed and the meeting had not broken up until midnight. It had been successfully argued (to secure the conviction of Orator Hunt in the aftermath of thePeterloo massacre

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter's Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England, on Monday 16 August 1819. Fifteen people died when cavalry charged into a crowd of around 60,000 people who had gathered to demand the reform of parliament ...

) that to be unlawful a meeting need only be ''one such that taking all the circumstances into consideration cannot but endanger the public peace, and raise fears and jealousies among the king's subjects''. Stephens was convicted and sentenced to eighteen months' imprisonment. He served his sentence in Chester Castle, under far from onerous conditions, and was released eight days early, to allow him to attend his father's funeral.

Later life

Heavy sureties had to be given for his good behaviour for the next five years, and he did not resume public speaking until participating in a campaign for better enforcement of the Ten Hours' Act (i.e. against the relay system) in 1849., explicitly holding non-compliance and non-enforcement to be responsible for social unrest and the more extreme forms that manifested itself in: "It is the practice of injustice towards the poor which estranges them from the institutions of their country, and leads them into many wild and unreasoning projects to obtain deliverance from the intolerable yoke that has been fastened upon them" He supported opposition to the 'Compromise Act' of 1850 and took part in abortive campaigns for legislation for a true ten-hour day enforced by stoppage of machinery. In 1857, he looked back on his agitational heyday

Heavy sureties had to be given for his good behaviour for the next five years, and he did not resume public speaking until participating in a campaign for better enforcement of the Ten Hours' Act (i.e. against the relay system) in 1849., explicitly holding non-compliance and non-enforcement to be responsible for social unrest and the more extreme forms that manifested itself in: "It is the practice of injustice towards the poor which estranges them from the institutions of their country, and leads them into many wild and unreasoning projects to obtain deliverance from the intolerable yoke that has been fastened upon them" He supported opposition to the 'Compromise Act' of 1850 and took part in abortive campaigns for legislation for a true ten-hour day enforced by stoppage of machinery. In 1857, he looked back on his agitational heyday

History would do justice to the memory of the benevolent and heroic men who had first devoted themselves to this great work (''factory reform''). Nothing gave him so much satisfaction in the retrospect, as the humble part he had been permitted to take in this good cause. That he, with them, had been misunderstood, misrepresented, and maligned, was only what was to be expected in the nature of things. It was a hard battle, and he had fought it; hard things had to be said and he had said them. It was no kid glove work they had to do, but work that required roughish handling. He had been impelled by a stern sense of duty in all he had done, and whilst doing it had never stayed to sigh over the sorrow, or quail before the opposition he had encountered. He was too busy and too proud to turn aside to enter into explanations and defence, knowing well that if he died in harness his motives would receive posthumous vindication; that if he lived the battle out, he should live misrepresentation and prejudice down. And so it had provedHe campaigned on the inadequacy and mal-distribution of relief during the Cotton Famine; attention was drawn to this and to Stephens' past history when there were riots on the relief issue in Stalybridge. In 1868 he lectured against disestablishment of the Irish Church. Stephens is buried in

St. John's Church St. John's Church, Church of St. John, or variants, thereof, (Saint John or St. John usually refers to John the Baptist, but also, sometimes, to John the Apostle or John the Evangelist) may refer to the following churches, former churches or other ...

in Dukinfield

Dukinfield is a town in Tameside, Greater Manchester, England, on the south bank of the River Tame opposite Ashton-under-Lyne, east of Manchester. At the 2011 Census, it had a population of 19,306.

Within the boundaries of the historic co ...

and commemorated by a blue plaque placed on the remains of the former Stalybridge Town Hall

Stalybridge Town Hall was a municipal building in Stamford Street, Stalybridge, Greater Manchester, England. The building, which was the meeting place of Stalybridge Borough Council, was a Grade II listed building.

History

Following a signific ...

and an obelisk monument in Stamford Park. Rayner Stephens High School

Rayner Stephens High School (formally Astley Sports College and Community High School) is a Mixed-sex education, coeducational secondary school located in Dukinfield in the English county of Greater Manchester.

It was a Community school (Englan ...

in Dukinfield is named after him.

Bibliography

Holyoake, George Jacob. (1881) ''Life of Joseph Rayner Stephens, preacher and political orator''. London: Williams and Norgate

:Issued to support the memorial appeal. Not so much a 'Life' as a collection of extensive quotations from a few letters and sermons - furthermore Holyoake (a Radical and free-thinker) is clearly not in sympathy with Stephens' political position (and perhaps does not understand it) Edwards, M.S. (1994). ''Purge This Realm – A Life of Joseph Rayner Stephens''. London: Epworth Press.

Notes

References

External links

* www.thepeoplescharter.co.ukSpartacus article on Joseph Rayner Stephens

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stephens, Joseph Rayner 1805 births 1879 deaths British Methodists Clergy from Edinburgh Burials in Greater Manchester