Joseph Moloney on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

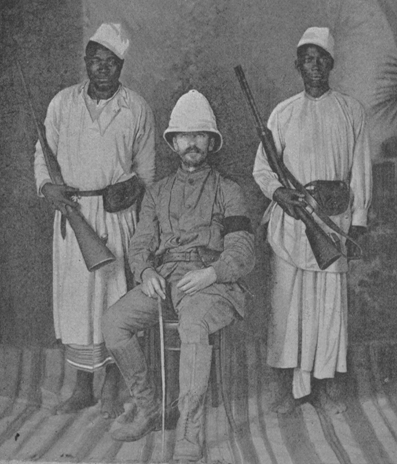

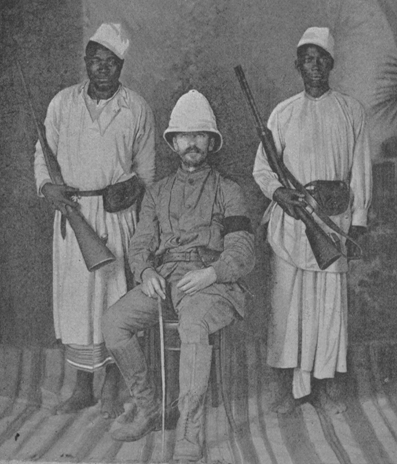

Joseph Moloney (1857 – 5 October 1896) was the

The expedition took a year for the round trip from their base in

The expedition took a year for the round trip from their base in

www.collin.francois.free.fr/Le_tour_du_monde/

Kingston and the Congo

''Ancestors'' September 2008 pp. 44–46 {{DEFAULTSORT:Moloney, Joseph Explorers of Africa British military personnel of the First Boer War Military personnel from Newry Royal Army Medical Corps officers 1857 births 1896 deaths Alumni of Trinity College Dublin Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society

Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

-born medical officer on the 1891–92 Stairs Expedition which seized Katanga in Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo ...

for the Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

King Leopold II, killing its ruler, Msiri, in the process. Dr Moloney took charge of the expedition for a few weeks when its military officers were dead or incapacitated by illness, and wrote a popular account of it, ''With Captain Stairs to Katanga: Slavery and Subjugation in the Congo 1891–92'', published in 1893.Joseph A. Moloney: ''With Captain Stairs to Katanga: Slavery and Subjugation in the Congo 1891–92''. Sampson Low, Marston & Company, London, 1893 (reprinted by Jeppestown Press, )

Early career

Born Joseph Augustus Moloney inNewry

Newry (; ) is a City status in Ireland, city in Northern Ireland, divided by the Newry River, Clanrye river in counties County Armagh, Armagh and County Down, Down, from Belfast and from Dublin. It had a population of 26,967 in 2011.

Newry ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, in 1857, he studied at Trinity College Dublin

, name_Latin = Collegium Sanctae et Individuae Trinitatis Reginae Elizabethae juxta Dublin

, motto = ''Perpetuis futuris temporibus duraturam'' (Latin)

, motto_lang = la

, motto_English = It will last i ...

and St Thomas's Hospital

St Thomas' Hospital is a large National Health Service, NHS teaching hospital in Central London, England. It is one of the institutions that compose the King's Health Partners, an academic health science centre. Administratively part of the Guy' ...

, London. He practised medicine in South London, and was a sportsman and yachtsman, with a taste for adventure, and was said to be 'hard as nails'. He served as a military doctor in the First Boer War

The First Boer War ( af, Eerste Vryheidsoorlog, literally "First Freedom War"), 1880–1881, also known as the First Anglo–Boer War, the Transvaal War or the Transvaal Rebellion, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 betwee ...

in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

, and as medical officer on an expedition to Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria t ...

, returning in 1890. website accessed 29 April 2007. On the strength of this, he was appointed by the Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

mercenary

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any ...

Captain William Stairs as one of five Europeans on his well-armed mission with 336 African askari

An askari (from Somali, Swahili and Arabic , , meaning "soldier" or "military", which also means "police" in the Somali language) was a local soldier serving in the armies of the European colonial powers in Africa, particularly in the African G ...

s and porters to take possession of Katanga for Leopold's Congo Free State, with or without Msiri's consent.

With Captain Stairs to Katanga

The expedition took a year for the round trip from their base in

The expedition took a year for the round trip from their base in Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

to Msiri's capital at Bunkeya

Bunkeya is a community in the Lualaba Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

It is located on a huge plain near the Lufira River.

Before the Belgian colonial conquest, Bunkeya was the center of a major trading state under the ruler Msir ...

, where they stayed nearly two months. They suffered disease, starvation for a while, and numerous hardships. A quarter of the Africans and two out of the five Europeans died, including Captain Stairs, but Moloney was spared any severe illness. In Bunkeya, Msiri refused to sign a treaty accepting Leopold's sovereignty and the CFS flag, and was killed by second officer Omer Bodson who had recklessly confronted Msiri in a situation which he, Bodson, could not control. Msiri's people and his successor as chief, seeing the expedition's greater firepower, bowed to the inevitable and signed the treaty. Katanga became part of Leopold's Congo Free State, which achieved later notoriety thanks to the treatment of the Congolese citizens.

Moloney's book has a significant omission. As evidence of Msiri's 'barbarity', it notes that he placed the heads and skulls of executed enemies and miscreants on poles and the palisades of his boma. An article in French was published in Paris around the same time as Moloney's book in which Moloney's colleague on the expedition, the Marquis Christian de Bonchamps

The Marquis Christian de Bonchamps (15 June 1860 – 9 December 1919) was a French explorer in Africa and a Colonialism, colonial officer in the French colonial empire, French Empire during the late 19th- early 20th-century epoch known as the ...

, revealed that after killing him, they cut off Msiri's head and hoisted it on a pole in plain view as a 'barbaric lesson' to his people.René de Pont-Jest: ''L'Expédition du Katanga, d'après les notes de voyage du marquis Christian de BONCHAMPS'', in: Edouard Charton (editor): ''Le Tour du Monde'' magazine, also published bound in two volumes by Hachette, Paris (1893). Available online awww.collin.francois.free.fr/Le_tour_du_monde/

Moloney's character

Moloney was in the main conventional in his approach to his job as expedition medical officer, and loyal to his commander and employer. At times he wrote appreciatively of many of the Africans on the expedition, particularly 'chief' (meaning supervisor) Hamadi-bin-Malum and some of theZanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

i askaris and porters. He also went against the conventional wisdom in the colonial service by noting the decency and humanity of many of the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

in East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fac ...

and Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo ...

, opining that they had a much better relationship with the Bantu people

The Bantu peoples, or Bantu, are an ethnolinguistic grouping of approximately 400 distinct ethnic groups who speak Bantu languages. They are native to 24 countries spread over a vast area from Central Africa to Southeast Africa and into Southern ...

than his colleagues would admit. As a doctor, Moloney treated African villagers who were brought to him as much as his medical stores would allow.

On the other hand, in his writing Moloney was untroubled by any notion that the killing of Msiri might have been unjustified or that the seizing of Katanga for Leopold was theft of territory. He wrote that Msiri was a bloodthirsty tyrant and despot from whose rule the local people had been liberated by the expedition, and that Bodson had killed Msiri in self-defence.

He did address the point that as British subjects in the King of Belgium's service, he and Stairs might come into armed conflict with competing British interests (the British South Africa Company of Cecil Rhodes). He wrote that in this eventuality they would discharge their duties to their employer, but he did not consider what other British people might think of this. Moloney did not think of Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

as a serious rival to the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, unlike France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

or Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

.Moloney, 1893: p.12.

Moloney's obituary in ''The Times'' of London described him as 'very valiant' and credited his leadership of the expedition, while Captain Stairs was ill and after the death of Bodson, with consolidation of control of Katanga and construction of a strong fort, enabling the following Belgian relief expeditions to establish firm control.''The Times'': "Obituary of Dr. Joseph Moloney, L.R.C.P.I., Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society, An Explorer". London, 7 October 1896.

After Katanga

On return to London, Moloney lectured and wrote papers on the geography of the expedition's route, and was appointed a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. He resided inNew Malden

New Malden is an area in South West London, England. It is located mainly within the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames and the London Borough of Merton, and is from Charing Cross. Neighbouring localities include Kingston, Norbiton, Raynes ...

, south-west London.

In 1895, Dr Moloney returned to central Africa with an expedition, this time with the British South Africa Company (which had been his competitor in the Stairs Expedition) to negotiate treaties with African chiefs in North-Eastern Rhodesia

North-Eastern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in south central Africa formed in 1900.North-Eastern Rhodesia Order in Council, 1900 The protectorate was administered under charter by the British South Africa Company. It was one of what were ...

. This was a more peaceful expedition than the Stairs Expedition, and was fairly successful, except in the case of Mpeseni, the Ngoni chief based near what is now Chipata. The Ngoni were of Zulu origin with a similar warrior tradition. Moloney spent two days there with Mpeseni, but left empty-handed. Two years later Mpeseni and his warriors went to war against the British but were defeated.

Perhaps because of his later service for the BSAC, or perhaps because his role was considered subordinate, Dr Moloney's reputation does not seem to have been subject to the same hostility that the British in Northern Rhodesia later directed towards the reputation of Captain Stairs for claiming Katanga for the Belgians.

Joseph Moloney returned to south-west London but did not have time to enjoy his status as a celebrated explorer: he died at the age of 38, and is buried in Kingston Cemetery in Kingston upon Thames

Kingston upon Thames (hyphenated until 1965, colloquially known as Kingston) is a town in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, southwest London, England. It is situated on the River Thames and southwest of Charing Cross. It is notable ...

.

References

Further reading

* Dr. Steven WoodbridgKingston and the Congo

''Ancestors'' September 2008 pp. 44–46 {{DEFAULTSORT:Moloney, Joseph Explorers of Africa British military personnel of the First Boer War Military personnel from Newry Royal Army Medical Corps officers 1857 births 1896 deaths Alumni of Trinity College Dublin Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society