Joseph Hooker on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

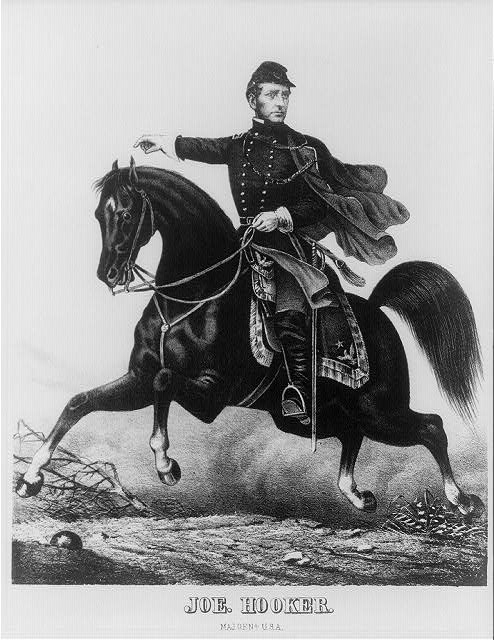

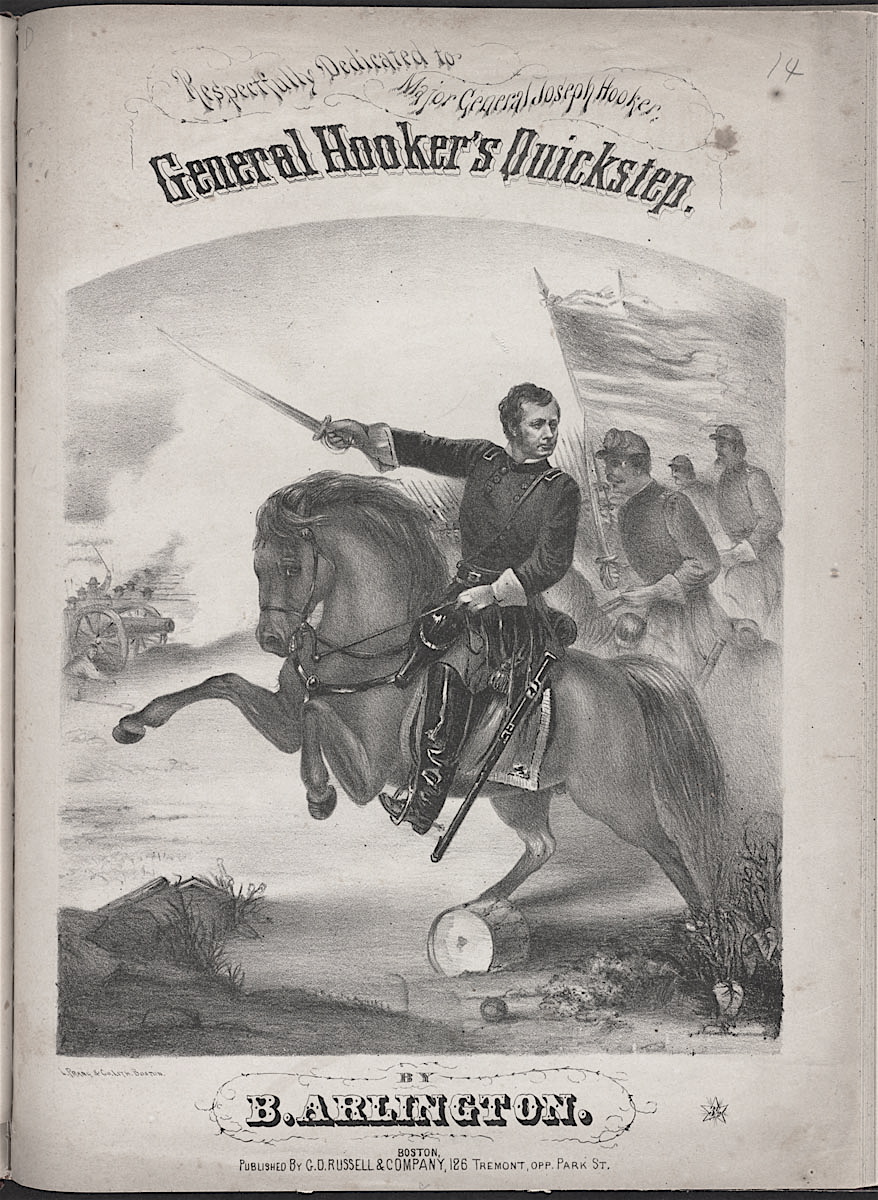

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by

Lincoln appointed Hooker to command of the

Lincoln appointed Hooker to command of the

Hooker's plan for the spring and summer campaign was both elegant and promising. He first planned to send his cavalry corps deep into the enemy's rear, disrupting supply lines and distracting him from the main attack. He would pin down Robert E. Lee's much smaller army at Fredericksburg while taking the large bulk of the Army of the Potomac on a flanking march to strike Lee in his rear. Defeating Lee, he could move on to seize Richmond. Unfortunately for Hooker and the Union, the execution of his plan did not match the elegance of the plan itself. The cavalry raid was conducted cautiously by its commander,

Hooker's plan for the spring and summer campaign was both elegant and promising. He first planned to send his cavalry corps deep into the enemy's rear, disrupting supply lines and distracting him from the main attack. He would pin down Robert E. Lee's much smaller army at Fredericksburg while taking the large bulk of the Army of the Potomac on a flanking march to strike Lee in his rear. Defeating Lee, he could move on to seize Richmond. Unfortunately for Hooker and the Union, the execution of his plan did not match the elegance of the plan itself. The cavalry raid was conducted cautiously by its commander,

Hooker's military career was not ended by his poor performance in the summer of 1863. He went on to regain a reputation as a solid corps commander when he was transferred with the XI and

Hooker's military career was not ended by his poor performance in the summer of 1863. He went on to regain a reputation as a solid corps commander when he was transferred with the XI and

After the war, Hooker led Lincoln's funeral procession in

After the war, Hooker led Lincoln's funeral procession in

''Ghosts of D.C.'' website

accessed September 10, 2013.

There is an

''Forty For the Union: Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery''

(Cincinnati Civil War Roundtable biography of Hooker). * Catton, Bruce. ''Glory Road''. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1952. . * Eicher, John H., and

''Battles and Leaders of the Civil War''

4 vols. New York: Century Co., 1884–1888. . * Lincoln, Abraham

January 26, 1863. * Sears, Stephen W. ''Chancellorsville''. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996. . * Sears, Stephen W. ''To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign''. Ticknor and Fields, 1992. . * Smith, Gene

"The Destruction of Fighting Joe Hooker."

''American Heritage'', October 1993. * Tsouras, Peter G. ''Major General George H. Sharpe and the Creation of American Military Intelligence in the Civil War''. Casemate, 2018. . * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. .

"Fighting Joe" Hooker Biography and timeline

Joseph Hooker in ''Encyclopedia Virginia''

in

Timeline of Hooker's life, Sonoma League

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Hooker, Joseph 1814 births 1879 deaths People from Hadley, Massachusetts American Unitarians American people of English descent Union Army generals People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War People from Long Island American military personnel of the Mexican–American War Members of the Aztec Club of 1847 United States Military Academy alumni Burials at Spring Grove Cemetery History of Sonoma County, California By: nsert name

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

in 1863.

Hooker had served in the Seminole Wars

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Geography of Florida, Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native Americans in the United States, Native American nation whi ...

and the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

, receiving three brevet promotions, before resigning from the Army. At the start of the Civil War, he joined the Union side as a brigadier general, distinguishing himself at Williamsburg, Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union ...

and Fredericksburg, after which he was given command of the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

.

His ambitious plan for Chancellorsville was thwarted by Lee's bold move in dividing his army and routing a Union corps, as well as by mistakes on the part of Hooker's subordinate generals and his own loss of nerve. The defeat handed Lee the initiative, which allowed him to travel north to Gettysburg.

Hooker was kept in command, but when General Halleck and Lincoln declined his request for reinforcements, he resigned. George G. Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. H ...

was appointed to command the Army of the Potomac three days before Gettysburg.

Hooker returned to combat in November 1863, helping to relieve the besieged Union Army at Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

, and continuing in the Western Theater under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

, but departed in protest before the end of the Atlanta Campaign when he was passed over for promotion.

Hooker became known as "Fighting Joe" following a journalist's clerical error, and the nickname stuck. His personal reputation was as a hard-drinking ladies' man, and his headquarters were known for parties and gambling.

Early years

Hooker was born inHadley, Massachusetts

Hadley (, ) is a town in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 5,325 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area. The area around the Hampshire and Mountain Farms Ma ...

, the grandson of a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. He was of entirely English ancestry, all of whom had been in New England since the early 1600s. His initial schooling was at the local Hopkins Academy

Hopkins Academy is the public middle (7th and 8th grade) and senior (9th–12th grade) high school for the town of Hadley, Massachusetts, United States.

Founding

The school was founded in 1664 with an endowment from Edward Hopkins, an English co ...

. He graduated from the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

in 1837, ranked 29th out of a class of 50, and was commissioned a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

in the 1st U.S. Artillery. His initial assignment was in Florida fighting in the second of the Seminole Wars

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Geography of Florida, Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native Americans in the United States, Native American nation whi ...

. He served in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

in staff positions in the campaigns of both Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

and Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

. He received brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

promotions for his staff leadership and gallantry in three battles: Monterrey

Monterrey ( , ) is the capital and largest city of the northeastern state of Nuevo León, Mexico, and the third largest city in Mexico behind Guadalajara and Mexico City. Located at the foothills of the Sierra Madre Oriental, the city is anchor ...

(to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

), National Bridge (major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

), and Chapultepec

Chapultepec, more commonly called the "Bosque de Chapultepec" (Chapultepec Forest) in Mexico City, is one of the largest city parks in Mexico, measuring in total just over 686 hectares (1,695 acres). Centered on a rock formation called Chapultep ...

(lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

). His future Army reputation as a ladies' man began in Mexico, where local women referred to him as the "Handsome Captain".Smith, np.

After the Mexican–American War (which ended in 1848), he served as an assistant adjutant general

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

of the Pacific Division, but resigned his commission in 1853; his military reputation had been damaged when he testified against his former commander, General Scott, in the court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

for insubordination of Gideon Johnson Pillow

Gideon Johnson Pillow (June 8, 1806 – October 8, 1878) was an American lawyer, politician, speculator, slaveowner, United States Army major general of volunteers during the Mexican–American War and Confederate brigadier general in the Ameri ...

. Hooker struggled with the tedium of peacetime life and reportedly passed the time with liquor, ladies, and gambling. He settled in Sonoma County, California

Sonoma County () is a county (United States), county located in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 United States Census, its population was 488,863. Its county seat and largest city is Santa Rosa, California, Santa Rosa. It is to the n ...

, as a farmer and land developer, and ran unsuccessfully for election to represent the region in the California legislature. He was obviously unhappy and unsuccessful in his civilian pursuits because, in 1858, he wrote to Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd (June 1, 1806 – August 26, 1863) was the 31st Governor of Virginia, U.S. Secretary of War, and the Confederate general in the American Civil War who lost the crucial Battle of Fort Donelson.

Early family life

John Buchan ...

to request that his name "be presented to the president Buchanan as a candidate for a lieutenant colonelcy", but nothing came of his request. From 1859 to 1861, he held a commission as a colonel in the California militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

.Eicher, p. 304.

Civil War

At the start of the Civil War in 1861, Hooker requested a commission, but his first application was rejected, possibly because of the lingering resentment harbored by Winfield Scott, general-in-chief of the Army. He had to borrow money to make the trip east from California. After he witnessed theUnion Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

, he wrote a letter to President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

that complained of military mismanagement, promoted his own qualifications, and again requested a commission. He was appointed, in August 1861, as brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

of volunteers to rank from May 17. He commanded a brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

Br ...

and then division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

around Washington, D.C., as part of the effort to organize and train the new Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

, under Maj. Gen.

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

.

1862

In the Peninsula Campaign of 1862, Hooker commanded the 2nd Division of the III Corps and made a good name for himself as a combat leader who handled himself well and aggressively sought out the key points on battlefields. He led his division with distinction at Williamsburg and at Seven Pines. Hooker's division did not play a major role in theSeven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, command ...

, although he and fellow division commander Phil Kearny tried unsuccessfully to urge McClellan to counterattack the Confederates. He chafed at the cautious generalship of McClellan and openly criticized his failure to capture Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

. Of his commander, Hooker said, "He is not only not a soldier, but he does not know what soldiership is." The Peninsula cemented two further reputations of Hooker's: his devotion to the welfare and morale of his men, and his hard-drinking social life, even on the battlefield.

On July 26, Hooker was promoted to major general, ranked from May 5. During the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

, the III Corps was sent to reinforce John Pope's Army of Virginia

The Army of Virginia was organized as a major unit of the Union Army and operated briefly and unsuccessfully in 1862 in the American Civil War. It should not be confused with its principal opponent, the Confederate Army of ''Northern'' Virginia ...

. Following Second Bull Run, Hooker replaced Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command o ...

as commander of the Army of Virginia's III Corps, which soon redesignated the I Corps of the Army of the Potomac. During the Maryland Campaign, Hooker led the I Corps at South Mountain and at Antietam, his corps launched the first assault of the bloodiest day in American history, driving south into the corps of Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

, where they fought each other to a standstill. Hooker, aggressive and inspiring to his men, left the battle early in the morning with a foot wound. He asserted that the battle would have been a decisive Union victory if he had managed to stay on the field, but General McClellan's caution once again failed the Northern troops and Lee's much smaller army eluded destruction. With his patience at an end, President Lincoln replaced McClellan with Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

. Although Hooker had criticized McClellan persistently, the latter was apparently unaware of it and in early October, shortly before his termination, had recommended that Hooker receive a promotion to brigadier general in the regular army. The War Department promptly acted on this recommendation, and Hooker received his brigadier's commission to rank from September 20. This promotion ensured that he would remain a general after the war was over and not revert to the rank of captain or lieutenant colonel.

December 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat, between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnsi ...

was another Union debacle. Upon recovering from his foot wound, Hooker was briefly made commander of V Corps 5th Corps, Fifth Corps, or V Corps may refer to:

France

* 5th Army Corps (France)

* V Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* V Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Ar ...

but was then promoted to "Grand Division" command, with a command that consisted of both III and V Corps. Hooker derided Burnside's plan to assault the fortified heights behind the city, deeming them "preposterous". His Grand Division (particularly V Corps) suffered serious losses in fourteen futile assaults ordered by Burnside over Hooker's protests. Burnside followed up this battle with the humiliating Mud March in January and Hooker's criticism of his commander bordered on formal insubordination. He described Burnside as a "wretch ... of blundering sacrifice." Burnside planned a wholesale purge of his subordinates, including Hooker, and drafted an order for the president's approval. He stated that Hooker was "unfit to hold an important commission during a crisis like the present." But Lincoln's patience had again run out and he removed Burnside instead.

Army of the Potomac

Lincoln appointed Hooker to command of the

Lincoln appointed Hooker to command of the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

on January 26, 1863. Some members of the army saw this move as inevitable, given Hooker's reputation for aggressive fighting, something sorely lacking in his predecessors. During the "Mud March" Hooker was quoted by a ''New York Times'' army correspondent as saying that "Nothing would go right until we had a dictator, and the sooner the better." Lincoln wrote a letter to the newly appointed general, part of which stated,

During the spring of 1863, Hooker established a reputation as an outstanding administrator and restored the morale of his soldiers, which had plummeted to a new low under Burnside. Among his changes were fixes to the daily diet of the troops, camp sanitary changes, improvements and accountability of the quartermaster system, addition of and monitoring of company cooks, several hospital reforms, and an improved furlough system (one man per company by turn, 10 days each). He created the Bureau of Military Information

The Bureau of Military Information (BMI) was the first formal and organized American intelligence agency, active during the American Civil War.

Predecessors

Allan Pinkerton was contracted by Federal and a number of state and local governments to s ...

, which was the first all-source intelligence organization employed by the U.S. military. He also implemented corps badges as a means of identifying units during battle or when marching and to instill unit pride in the men. Other orders addressed the need to stem rising desertion (one from Lincoln combined with incoming mail review, the ability to shoot deserters, and better camp picket lines), more and better drills, stronger officer training, and for the first time, combining the federal cavalry into a single corps. The corps badge idea was suggested by Hooker's chief of staff, Daniel Butterfield

Daniel Adams Butterfield (October 31, 1831 – July 17, 1901) was a New York businessman, a Union general in the American Civil War, and Assistant Treasurer of the United States.

After working for American Express, co-founded by his father, ...

(Sears, ''Chancellorsville'', p. 72). Hooker said of his revived army:

Also during this winter, Hooker made several high-level command changes, including with his corps commanders. Both "Left Grand Division" commander Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin, who vowed that he would not serve under Hooker, and II Corps commander Maj. Gen. Edwin Vose Sumner

Edwin Vose Sumner (January 30, 1797March 21, 1863) was a career United States Army officer who became a Union Army general and the oldest field commander of any Army Corps on either side during the American Civil War. His nicknames "Bull" or "Bul ...

was relieved of command, on Burnside's recommendation, in the same order appointing Hooker to command. The IX Corps 9 Corps, 9th Corps, Ninth Corps, or IX Corps may refer to:

France

* 9th Army Corps (France)

* IX Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* IX Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial Germ ...

was a potential source of embarrassment or friction within the army because it was Burnside's old corps, so it was detached as a separate organization and sent to the Virginia Peninsula

The Virginia Peninsula is a peninsula in southeast Virginia, USA, bounded by the York River, James River, Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay. It is sometimes known as the ''Lower Peninsula'' to distinguish it from two other peninsulas to the ...

under the command of Brig. Gen. William F. "Baldy" Smith, former commander of VI Corps 6 Corps, 6th Corps, Sixth Corps, or VI Corps may refer to:

France

* VI Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry formation of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VI Corps (Grande Armée), a formation of the Imperial French army du ...

. (Both Franklin and Smith were considered suspect by Hooker because of their previous political maneuvering against Burnside and on behalf of McClellan.)

For the important position of chief of staff, Hooker asked the War Department to send him Brig. Gen. Charles Stone, however, this was denied. Stone had been relieved, arrested, and imprisoned for his role in the Battle of Ball's Bluff

The Battle of Ball's Bluff was an early battle of the American Civil War fought in Loudoun County, Virginia, on October 21, 1861, in which Union Army forces under Major General George B. McClellan suffered a humiliating defeat.

The operation was ...

in the fall of 1861, despite the lack of any trial. Stone did not receive a command upon his release, mostly due to political pressures, which left him militarily exiled and disgraced. Army of the Potomac historian and author Bruce Catton

Charles Bruce Catton (October 9, 1899 – August 28, 1978) was an American historian and journalist, known best for his books concerning the American Civil War. Known as a narrative historian, Catton specialized in popular history, featuring int ...

termed this request by Hooker "a strange and seemingly uncharacteristic thing" and "one of the most interesting things he ever did." Hooker never explained why he asked for Stone, but Catton believed:

Despite this, Fighting Joe would set a very bad example for the conduct of generals and their staff and subordinates. His headquarters in Falmouth, Virginia

Falmouth is a census-designated place (CDP) in Stafford County, Virginia, United States. Situated on the north bank of the Rappahannock River at the falls, the community is north of and opposite the city of Fredericksburg. Recognized by the U. ...

, was described by cavalry officer Charles F. Adams, Jr., as being a combination of a "bar-room and a brothel

A brothel, bordello, ranch, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in sexual activity with prostitutes. However, for legal or cultural reasons, establishments often describe themselves as massage parlors, bars, strip clubs, body rub par ...

". He built a network of loyal political cronies that included Maj. Gen. Dan Butterfield for chief of staff, and the notorious political general

A political general is a general officer or other military leader without significant military experience who is given a high position in command for political reasons, through political connections, or to appease certain political blocs and fact ...

, Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, for command of the III Corps.

Chancellorsville

Hooker's plan for the spring and summer campaign was both elegant and promising. He first planned to send his cavalry corps deep into the enemy's rear, disrupting supply lines and distracting him from the main attack. He would pin down Robert E. Lee's much smaller army at Fredericksburg while taking the large bulk of the Army of the Potomac on a flanking march to strike Lee in his rear. Defeating Lee, he could move on to seize Richmond. Unfortunately for Hooker and the Union, the execution of his plan did not match the elegance of the plan itself. The cavalry raid was conducted cautiously by its commander,

Hooker's plan for the spring and summer campaign was both elegant and promising. He first planned to send his cavalry corps deep into the enemy's rear, disrupting supply lines and distracting him from the main attack. He would pin down Robert E. Lee's much smaller army at Fredericksburg while taking the large bulk of the Army of the Potomac on a flanking march to strike Lee in his rear. Defeating Lee, he could move on to seize Richmond. Unfortunately for Hooker and the Union, the execution of his plan did not match the elegance of the plan itself. The cavalry raid was conducted cautiously by its commander, Brig. Gen.

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

George Stoneman

George Stoneman Jr. (August 8, 1822 – September 5, 1894) was a United States Army cavalry officer and politician who served as the fifteenth Governor of California from 1883 to 1887. He was trained at West Point, where his roommate was Stonewall ...

, and met none of its objectives. The flanking march went well enough, achieving strategic surprise, but when he attempted to advance with three columns, Stonewall Jackson's surprise attack on May 1 pushed Hooker back and caused him to withdraw his troops. From there, Hooker pulled his army back to Chancellorsville and waited for Lee to attack. Lee audaciously split his smaller army in two to deal with both parts of Hooker's army. Then, he split again, sending Stonewall Jackson's corps on its own flanking march, striking Hooker's exposed right flank and routing the Union XI Corps 11 Corps, 11th Corps, Eleventh Corps, or XI Corps may refer to:

* 11th Army Corps (France)

* XI Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* XI Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army

* ...

. The Army of the Potomac dropped into a purely defensive mode and eventually was forced to retreat.

The Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

has been called "Lee's perfect battle" because of his ability to vanquish a much larger foe through audacious tactics. Part of Hooker's failure can be attributed to an encounter with a cannonball; while he was standing on the porch of his headquarters, the missile struck a wooden column against which he was leaning, initially knocking him senseless, and then putting him out of action for the rest of the day with a concussion

A concussion, also known as a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), is a head injury that temporarily affects brain functioning. Symptoms may include loss of consciousness (LOC); memory loss; headaches; difficulty with thinking, concentration, ...

. Despite his incapacitation, he refused entreaties to turn over temporary command of the army to his second-in-command, Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch. Several of his subordinate generals, including Couch and Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum, openly questioned Hooker's command decisions. Couch was so disgusted that he refused to ever serve under Hooker again. Political winds blew strongly in the following weeks as generals maneuvered to overthrow Hooker or to position themselves if Lincoln decided on his own to do so.

Robert E. Lee once again began an invasion of the North, in June 1863, and Lincoln urged Hooker to pursue and defeat him. Hooker's initial plan was to seize Richmond instead, but Lincoln immediately vetoed that idea, so the Army of the Potomac began to march north, attempting to locate Lee's Army of Northern Virginia as it slipped down the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge- ...

into Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. Hooker's mission was first to protect Washington, D.C., and Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

and second to intercept and defeat Lee. Unfortunately, Lincoln was losing any remaining confidence he had in Hooker. Hooker's senior officers expressed to Lincoln their lack of confidence in Hooker, as did Henry Halleck, Lincoln's General-in-chief. When Hooker got into a dispute with Army headquarters over the status of defensive forces in Harpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where the U.S. stat ...

, he impulsively offered his resignation in protest, which was quickly accepted by Lincoln and General-in-chief Henry W. Halleck

Henry Wager Halleck (January 16, 1815 – January 9, 1872) was a senior United States Army officer, scholar, and lawyer. A noted expert in military studies, he was known by a nickname that became derogatory: "Old Brains". He was an important par ...

. On June 28, 1863, three days before the climactic Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

, Hooker was replaced by Maj. Gen. George Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate States Army, Confederate Full General (CSA), General Robert E. Lee at the Battle ...

. Hooker received the Thanks of Congress The Thanks of Congress is a series of formal resolutions passed by the United States Congress originally to extend the government's formal thanks for significant victories or impressive actions by American military commanders and their troops. Altho ...

for his role at the start of the Gettysburg Campaign, but the glory would go to Meade. Hooker's tenure as head of the Army of the Potomac had lasted 5 months.

Western Theater

Hooker's military career was not ended by his poor performance in the summer of 1863. He went on to regain a reputation as a solid corps commander when he was transferred with the XI and

Hooker's military career was not ended by his poor performance in the summer of 1863. He went on to regain a reputation as a solid corps commander when he was transferred with the XI and XII Corps 12th Corps, Twelfth Corps, or XII Corps may refer to:

* 12th Army Corps (France)

* XII Corps (Grande Armée), a corps of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* XII (1st Royal Saxon) Corps, a unit of the Imperial German Army

* XII ...

of the Army of the Potomac westward to reinforce the Army of the Cumberland

The Army of the Cumberland was one of the principal Union armies in the Western Theater during the American Civil War. It was originally known as the Army of the Ohio.

History

The origin of the Army of the Cumberland dates back to the creation ...

around Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

. Hooker was in command at the Battle of Lookout Mountain

The Battle of Lookout Mountain also known as the Battle Above The Clouds was fought November 24, 1863, as part of the Chattanooga Campaign of the American Civil War. Union forces under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker assaulted Lookout Mountain, Chattan ...

, playing an important role in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

's decisive victory at the Battle of Chattanooga. He was brevetted to major general in the regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregulars, irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenary, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the ...

for his success at Chattanooga, but he was disappointed to find that Grant's official report of the battle credited his friend William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

's contribution over Hooker's.

Hooker led his corps (now designated the XX Corps) competently in 1864 Atlanta Campaign under Sherman but asked to be relieved before the capture of the city because of his dissatisfaction with the promotion of Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard to the command of the Army of the Tennessee

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, upon the death of Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson

James Birdseye McPherson (November 14, 1828 – July 22, 1864) was a career United States Army officer who served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. McPherson was on the General's staff of Henry Halleck and late ...

. Not only did Hooker have seniority over Howard, but he also blamed Howard in large part for his defeat at Chancellorsville (Howard had commanded the XI Corps 11 Corps, 11th Corps, Eleventh Corps, or XI Corps may refer to:

* 11th Army Corps (France)

* XI Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* XI Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army

* ...

, which had borne the brunt of Jackson's flank attack). Hooker's biographer reports that there were numerous stories indicating that Abraham Lincoln attempted to intercede with Sherman, urging that Hooker be appointed to command the Army of Tennessee, but Sherman threatened to resign if the president insisted. However, due to "obvious gaps" in the Official Records

The ''Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion'', commonly known as the ''Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies'' or Official Records (OR or ORs), is the most extensive collection of Americ ...

, the story cannot be verified.

After leaving Georgia, Hooker commanded the Northern Department (comprising the states of Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, and Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

), headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, from October 1, 1864, until the end of the war. While in Cincinnati he married Olivia Groesbeck, sister of Congressman

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivalen ...

William S. Groesbeck.

Final years

After the war, Hooker led Lincoln's funeral procession in

After the war, Hooker led Lincoln's funeral procession in Springfield

Springfield may refer to:

* Springfield (toponym), the place name in general

Places and locations Australia

* Springfield, New South Wales (Central Coast)

* Springfield, New South Wales (Snowy Monaro Regional Council)

* Springfield, Queenslan ...

on May 4, 1865. He served in command of the Department of the East

The Department of the East was a military administrative district established by the U.S. Army several times in its history. The first was from 1853 to 1861, the second Department of the East, from 1863 to 1873, and the last from 1877 to 1913.

H ...

and Department of the Lakes The Department of the Lakes was a military department of the United States Army that existed from 1866 to 1873 and again from 1898 to 1913. It was subordinate to the Military Division of the Atlantic and comprised posts in the Midwestern United Sta ...

following the war. His postbellum life was marred by poor health and he was partially paralyzed by a stroke. He was mustered out of the volunteer service on September 1, 1866, and retired from the U.S. Army on October 15, 1868, with the regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregulars, irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenary, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the ...

rank of major general. He died on October 31, 1879, while on a visit to Garden City, New York

Garden City is a village located on Long Island in Nassau County New York. It is the Greater Garden City area's anchor community. The population was 23,272 at the 2020 census.

The Incorporated Village of Garden City is primarily located within ...

, and is buried in Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, his wife's hometown.

Legacy

Hooker was popularly known as "Fighting Joe" Hooker, a nickname he regretted deeply; he said, "People will think I am a highwayman or a bandit." When a newspaper dispatch arrived in New York during the Peninsula Campaign, a typographical error changed the entry "Fighting – Joe Hooker Attacks Rebels" to remove the dash and the name stuck. Robert E. Lee occasionally referred to him as "Mr. F. J. Hooker" in a mildly sarcastic jab at his opponent. Hooker's reputation as a hard-drinking ladies' man was established through rumors in the pre-Civil War Army and has been cited by a number of popular histories. Biographer Walter H. Hebert describes the general's personal habits as the "subject of much debate"Hebert, p. 65. although there was little debate in the popular opinion of the time. His men parodied Hooker in the popular war song ''Marching Along''. The lines were replaced by Historian Stephen W. Sears, however, states that there is no basis for the claims that Hooker was a heavy drinker or that he was ever intoxicated on the battlefield. There is a popular legend that "hooker" as a slang term for a prostitute is derived from his last name because of parties and a lack of military discipline at his headquarters near theMurder Bay

Murder Bay was a disreputable slum in Washington D.C. roughly bounded by Constitution Avenue NW, Pennsylvania Avenue NW, and 15th Street NW. The area was a center of crime through the early 20th century, with an extensive criminal underclass a ...

district of Washington, DC. Some versions of the legend claim that the band of prostitutes that followed his division was derisively referred to as "General Hooker's Army" or "Hooker's Brigade." However, the term "hooker" was used in print as early as 1845, years before Hooker was a public figure, and is likely derived from the concentration of prostitutes around the shipyards and ferry terminal of the Corlear's Hook

The Lower East Side, sometimes abbreviated as LES, is a historic neighborhood in the southeastern part of Manhattan in New York City. It is located roughly between the Bowery and the East River from Canal to Houston streets.

Traditionally an im ...

area of Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

in the early to middle 19th century, who came to be referred to as "hookers". The prevalence of the Hooker legend may have been at least partly responsible for the popularity of the term. There is some evidence that an area in Washington, DC, known for prostitution during the Civil War, was referred to as "Hooker's Division". The name was shortened to "The Division" when he spent time there after First Bull Run guarding D.C. against incursion.accessed September 10, 2013.

equestrian statue

An equestrian statue is a statue of a rider mounted on a horse, from the Latin ''eques'', meaning 'knight', deriving from ''equus'', meaning 'horse'. A statue of a riderless horse is strictly an equine statue. A full-sized equestrian statue is a d ...

of General Hooker outside the Massachusetts State House

The Massachusetts State House, also known as the Massachusetts Statehouse or the New State House, is the List of state capitols in the United States, state capitol and seat of government for the Massachusetts, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, lo ...

in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, and Hooker County in Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

is named for him.

See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-ranke ...

* List of Massachusetts generals in the American Civil War

There were approximately 120 general officers from Massachusetts who served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. This list consists of generals who were either born in Massachusetts or lived in Massachusetts when they joined the army (i ...

* Massachusetts in the American Civil War

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts played a significant role in national events prior to and during the American Civil War (1861-1865). Massachusetts dominated the early antislavery movement during the 1830s, motivating activists across the nation. ...

References

;Specific ; Bibliography * Barnett, James''Forty For the Union: Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery''

(Cincinnati Civil War Roundtable biography of Hooker). * Catton, Bruce. ''Glory Road''. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1952. . * Eicher, John H., and

David J. Eicher

David John Eicher (born August 7, 1961) is an American editor, writer, and popularizer of astronomy and space. He has been editor-in-chief of ''Astronomy'' magazine since 2002. He is author, coauthor, or editor of 23 books on science and American ...

. ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. .

* Foote, Shelby. '' The Civil War: A Narrative''. Vol. 2, ''Fredericksburg to Meridian''. New York: Random House

Random House is an American book publisher and the largest general-interest paperback publisher in the world. The company has several independently managed subsidiaries around the world. It is part of Penguin Random House, which is owned by Germ ...

, 1958. .

* Hebert, Walter H. ''Fighting Joe Hooker''. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999. .

* Johnson, Robert Underwood, and Clarence C. Buel, eds''Battles and Leaders of the Civil War''

4 vols. New York: Century Co., 1884–1888. . * Lincoln, Abraham

January 26, 1863. * Sears, Stephen W. ''Chancellorsville''. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996. . * Sears, Stephen W. ''To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign''. Ticknor and Fields, 1992. . * Smith, Gene

"The Destruction of Fighting Joe Hooker."

''American Heritage'', October 1993. * Tsouras, Peter G. ''Major General George H. Sharpe and the Creation of American Military Intelligence in the Civil War''. Casemate, 2018. . * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. .

External links

"Fighting Joe" Hooker Biography and timeline

Joseph Hooker in ''Encyclopedia Virginia''

in

Sonoma, California

Sonoma is a city in Sonoma County, California, United States, located in the North Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area. Sonoma is one of the principal cities of California's Wine Country and the center of the Sonoma Valley AVA. Sonoma's p ...

Timeline of Hooker's life, Sonoma League

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Hooker, Joseph 1814 births 1879 deaths People from Hadley, Massachusetts American Unitarians American people of English descent Union Army generals People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War People from Long Island American military personnel of the Mexican–American War Members of the Aztec Club of 1847 United States Military Academy alumni Burials at Spring Grove Cemetery History of Sonoma County, California By: nsert name