Josef Thorak on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Josef Thorak (7 February 1889 in

Josef Thorak (7 February 1889 in

City of Salzburg, retrieved 29 July 2021 .Josephine Gabler

''Neue Deutsche Biographie'', 2016, retrieved 29 July 2021 . Some

With

With

''

the original

on 31 January 2011. In 1937, he was named professor of sculpture at the

In 1939 Thorak sculpted three oversize horses ( high) for the Nuremberg rally grounds."Putzkraft gesucht, halbtags"

In 1939 Thorak sculpted three oversize horses ( high) for the Nuremberg rally grounds."Putzkraft gesucht, halbtags"

''"Rechtsstreit um Hitlers Bronzepferde"

'' Gabriel Borrud

"Nazi propaganda horse winds up at German school"

''

File:Sterbender Krieger.JPG, ''Dying Warrior'' (1922)

Works by Josef Thorak

''Third Reich in Ruins'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Thorak, Josef 1889 births 1952 deaths Artists from Salzburg Austrian sculptors Austrian male sculptors German sculptors German male sculptors Nazi architecture 20th-century sculptors Olympic competitors in art competitions

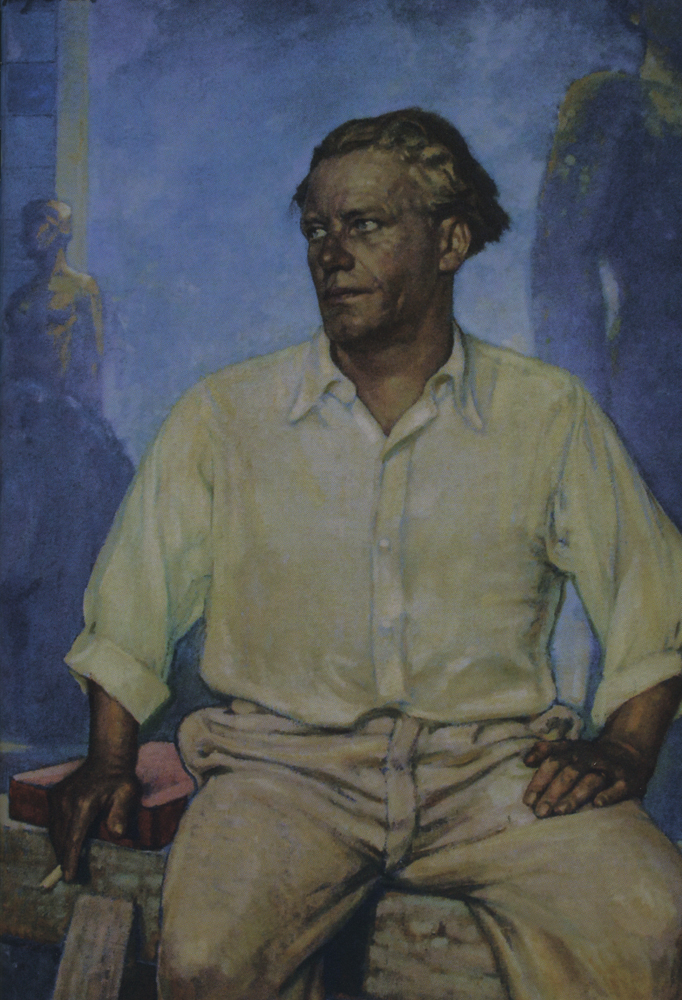

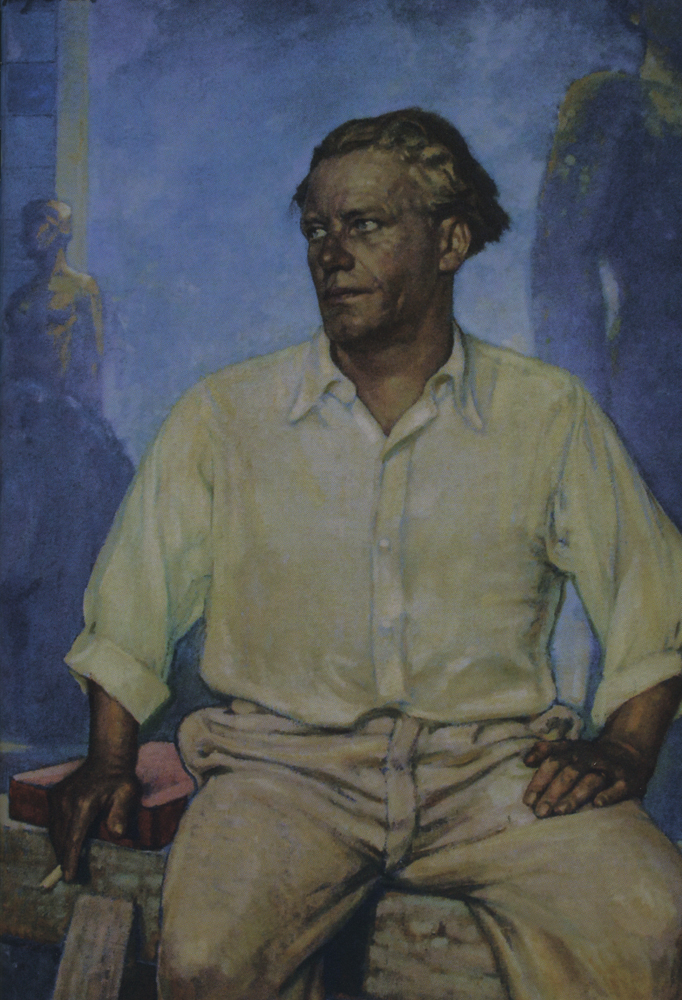

Josef Thorak (7 February 1889 in

Josef Thorak (7 February 1889 in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

– 26 February 1952 in Bad Endorf

Bad Endorf is a municipality in the district of Rosenheim in Bavaria in Germany. The relatively small town is located about 15 km outside of Rosenheim and is in close proximity to the Chiemsee lake and its larger shore towns, Prien, Gstad ...

, Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

) was an Austrian-German sculptor. He became known for oversize monumental sculptures, particularly of male figures, and was one of the most prominent sculptors of the Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

.

Early life and education

Thorak was born out of wedlock in Vienna. His father, also Josef Thorak, was fromEast Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

; his mother was from Salzburg, where she returned soon after his birth and the couple married in 1896. That year he was placed in a religious boarding school for neglected children, but his schooling ended after he set fire to his bed in late 1898 and was injured by a nun disciplining him, which led to a dispute in the press and the courts. In 1903 he began an apprenticeship as a potter

A potter is someone who makes pottery.

Potter may also refer to:

Places United States

*Potter, originally a section on the Alaska Railroad, currently a neighborhood of Anchorage, Alaska, US

* Potter, Arkansas

*Potter, Nebraska

* Potters, New Je ...

in Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

; after completion of this and of journeyman

A journeyman, journeywoman, or journeyperson is a worker, skilled in a given building trade or craft, who has successfully completed an official apprenticeship qualification. Journeymen are considered competent and authorized to work in that fie ...

years in Austria and Germany, he started work at a factory in Vienna and took classes from the sculptor Anton Hanak

Anton Hanak (22 March 1875, Brünn – 7 January 1934, Vienna) was an Austrian sculptor and art Professor. His works tend to have a visionary-symbolic character, related to Expressionism.

Biography

He studied with Edmund von Hellmer at the Ac ...

. From 1911 to 1915 he studied sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts

The following is a list of notable art schools.

Accredited non-profit art and design colleges

* Adelaide Central School of Art

* Alberta College of Art and Design

* Art Academy of Cincinnati

* Art Center College of Design

* The Art Institute o ...

, interrupted by two periods of service in the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and a study trip to the Balkans. Julius von Schlosser

Julius Alwin Franz Georg Andreas Ritter von Schlosser (23 September 1866, Vienna – 1 December 1938, Vienna) was an Austrian art historian and an important member of the Vienna School of Art History. According to Ernst Gombrich, he was "One of t ...

, Director of the Kunsthistorisches Museum

The Kunsthistorisches Museum ( "Museum of Art History", often referred to as the "Museum of Fine Arts") is an art museum in Vienna, Austria. Housed in its festive palatial building on the Vienna Ring Road, it is crowned with an octagonal do ...

, recommended him and he secured a studio under Ludwig Manzel

Karl Ludwig Manzel (3 June 1858, Neu Kosenow – 20 June 1936, Berlin) was a German sculptor, painter and graphic artist.

Life

His father was a tailor and his mother was a midwife. The family moved twice, first to Boldekow then, in 1867, to An ...

at the Prussian Academy of Arts

The Prussian Academy of Arts (German: ''Preußische Akademie der Künste'') was a state arts academy first established in Berlin, Brandenburg, in 1694/1696 by prince-elector Frederick III, in personal union Duke Frederick I of Prussia, and late ...

in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

; he joined the Berlin Secession

The Berlin Secession was an art movement established in Germany on May 2, 1898. Formed in reaction to the Association of Berlin Artists, and the restrictions on contemporary art imposed by Kaiser Wilhelm II, 65 artists "seceded," demonstrating ag ...

in 1917."NS-Strassennamen: Josef Thorak"City of Salzburg, retrieved 29 July 2021 .Josephine Gabler

''Neue Deutsche Biographie'', 2016, retrieved 29 July 2021 . Some

expressionist

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it rad ...

influences can be noticed in his generally neoclassical style.

Career

In Berlin in the 1920s, Thorak lived mainly on commissions to design cemetery monuments for soldiers, also assisting wealthy friends, many of them Jewish, with design work. He was helped by friendships withHjalmar Schacht

Hjalmar Schacht (born Horace Greeley Hjalmar Schacht; 22 January 1877 – 3 June 1970, ) was a German economist, banker, centre-right politician, and co-founder in 1918 of the German Democratic Party. He served as the Currency Commissioner ...

, President of the Reichsbank

The ''Reichsbank'' (; 'Bank of the Reich, Bank of the Realm') was the central bank of the German Reich from 1876 until 1945.

History until 1933

The Reichsbank was founded on 1 January 1876, shortly after the establishment of the German Empi ...

, and above all with the art museum director Wilhelm von Bode

Wilhelm von Bode (10 December 1845 – 1 March 1929) was a German art historian and museum curator. Born Arnold Wilhelm Bode in Calvörde, he was ennobled in 1913. He was the creator and first curator of the Kaiser Friedrich Museum, now calle ...

, who wrote a monograph on Thorak in 1929,Peter Adam, ''Art of the Third Reich'', New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992, , p. 190. said to have been his only book on a living artist.Jonathan Petropoulos,''The Faustian Bargain: The Art World in Nazi Germany'', Oxford University, 2000 (unpaginated online edition). He won a state prize in 1928. To promote himself, he began calling himself "professor". His commissions were reduced by the German economic crisis of the 1920s and the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

; eventually in 1932 he received a commission to design fittings for a church in Tegel, and he entered work in the sculpture event in the art competition at the 1932 Summer Olympics

The 1932 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the X Olympiad and also known as Los Angeles 1932) were an international multi-sport event held from July 30 to August 14, 1932 in Los Angeles, California, United States. The Games were held duri ...

.

After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Thorak took advantage of friendships with many prominent members of the Party. Through the film maker Luis Trenker

Luis Trenker (born Alois Franz Trenker, 4 October 1892 – 13 April 1990) was a South Tyrolean film producer, director, writer, actor, architect, Mountaineering, alpinist, and Bobsleigh, bobsledder.

Biography Early life

Alois Franz Trenker was b ...

, he was engaged after Hanak's death in 1934 to complete the ''Emniyet'' monument (Security Monument; now the Güven (Trust) Monument) in Ankara

Ankara ( , ; ), historically known as Ancyra and Angora, is the capital of Turkey. Located in the central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5.1 million in its urban center and over 5.7 million in Ankara Province, maki ...

, Turkey, and he sculpted busts of Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

and Ernst Hanfstaengl

Ernst Franz Sedgwick Hanfstaengl (; 2 February 1887 – 6 November 1975) was a German-American businessman and close friend of Adolf Hitler. He eventually fell out of favour with Hitler and defected from Nazi Germany to the United States. He lat ...

in addition to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

and Józef Piłsudski

), Vilna Governorate, Russian Empire (now Lithuania)

, death_date =

, death_place = Warsaw, Poland

, constituency =

, party = None (formerly PPS)

, spouse =

, children = Wan ...

. After the death of Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fro ...

in August 1934, Thorak sculpted his death mask

A death mask is a likeness (typically in wax or plaster cast) of a person's face after their death, usually made by taking a cast or impression from the corpse. Death masks may be mementos of the dead, or be used for creation of portraits. It ...

; his bust of Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

was given as an official gift by Hitler in 1940. For a bust of Hitler, he stayed for several days in 1936 at Hitler's Obersalzberg

Obersalzberg is a mountainside retreat situated above the market town of Berchtesgaden in Bavaria, Germany. Located about south-east of Munich, close to the border with Austria, it is best known as the site of Adolf Hitler's former mountain resi ...

compound. Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head of ...

arranged a solo exhibition for him in 1935. He became wealthy and in 1937 or 1938 bought near the Chiemsee

Chiemsee () is a freshwater lake in Bavaria, Germany, near Rosenheim. It is often called "the Bavarian Sea". The rivers Tiroler Achen and Prien flow into the lake from the south, and the river Alz flows out towards the north. The Alz flows in ...

in Bavaria; in 1943 he also acquired , which had been seized from the family of Hugo von Hofmannsthal

Hugo Laurenz August Hofmann von Hofmannsthal (; 1 February 1874 – 15 July 1929) was an Austrian novelist, librettist, poet, dramatist, narrator, and essayist.

Early life

Hofmannsthal was born in Landstraße, Vienna, the son of an upper-class ...

because of their Jewish ancestry. At Schloss Hartmannsberg he had a collection of medieval carvings and antique furnishings, some of which was obtained from the prominent Nazi art dealers Kajetan and Josef Mühlmann.

With

With Arno Breker

Arno Breker (19 July 1900 – 13 February 1991) was a German architect and sculptor who is best known for his public works in Nazi Germany, where they were endorsed by the authorities as the antithesis of degenerate art. He was made official ...

, he became one of the two "official sculptors" of the Third Reich."Art: Bigger Than Life"''

Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'', 31 July 1950, archived frothe original

on 31 January 2011. In 1937, he was named professor of sculpture at the

Munich Academy of Fine Arts

The Academy of Fine Arts, Munich (german: Akademie der Bildenden Künste München, also known as Munich Academy) is one of the oldest and most significant art academies in Germany. It is located in the Maxvorstadt district of Munich, in Bavaria, ...

; in 1939, Hitler decreed that a studio should be built for him in Baldham

Baldham is a district of Vaterstetten in the Upper Bavarian district of Ebersberg, Germany. It is located approximately 18 km east of the state capital Munich and 15 km west of the district capital Ebersberg.

Geography

Vaterstetten i ...

to Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, he ...

's design. Although he did not join the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

until 1941, Hitler ordered his membership backdated to 1933 for appearance's sake. After a visit with Hitler to Thorak's studio in 1937, Goebbels described him in his diary as "our greatest sculptural talent. He needs to be given commissions." In his ''Spandau Diaries'' written in prison after the war, Speer referred to Thorak as "more or less ''my'' sculptor, who frequently designed statues and reliefs for my buildings". Well known for his "grandiose monuments", Thorak was nicknamed "Professor Thorax" because of his preference for muscular neo-classical nude sculpture, typically "gazing fervently into the distance". In the late 1930s, he became less popular with the Nazi leadership than Breker, because of his less voluptuous female nudes; he returned to favour during the war years after producing female statues expressing pathos.

Later life and death

After theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Thorak at first produced decorative ceramics, and then focussed on religious sculpture. He was pronounced legally denazified

Denazification (german: link=yes, Entnazifizierung) was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by remov ...

in 1948 and, after two challenges, finally in 1951, and in July 1950 was permitted to hold a final exhibition at the Mirabell Palace

Mirabell Palace (german: Schloss Mirabell) is a historic building in the city of Salzburg, Austria. The palace with its gardens is a listed cultural heritage monument and part of the Historic Centre of the City of Salzburg UNESCO World Heritage Si ...

in Salzburg, which was well attended but poorly reviewed. His Austrian citizenship was restored in 1951. In February 1952, he died at Schloss Hartmannsberg in Bavaria, and was buried with his mother in St. Peter's cemetery.

Personal life

Thorak married three times. In 1918 he married Hertha Kroll; they had two sons, the older born before their marriage, in January 1917. The couple divorced in 1926 but continued to live together until her death in 1928. The following year he married Hilda Lubowski, with whom he had a third son, but after the Nazis came to power in 1933, the couple agreed to divorce because of her Jewish ancestry. She emigrated in 1939 to France and subsequently to England. In 1946, Thorak married Erna Hoenig, an American who had been living at Schloss Hartmannsberg since 1944; their son was born in 1949.Works

* 1922: ''Der sterbende Krieger'' (The Dying Warrior),World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

memorial in Stolpmünde, now Ustka

Ustka (pronounced ; csb, Ùskô; german: Stolpmünde) is a spa town in the Middle Pomerania region of northern Poland with 17,100 inhabitants (2001). It is part of Słupsk County in Pomeranian Voivodeship. It is located on the Slovincian Coast on ...

, Poland

* 1928: ''Heim'' (Home) and ''Arbeit'' (Work), Charlottenburg

Charlottenburg () is a Boroughs and localities of Berlin, locality of Berlin within the borough of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf. Established as a German town law, town in 1705 and named after Sophia Charlotte of Hanover, Queen consort of Kingdom ...

* 1936: ''Boxer'', modelled on Max Schmeling

Maximilian Adolph Otto Siegfried Schmeling (, ; 28 September 1905 – 2 February 2005) was a German boxing, boxer who was heavyweight champion of the world between 1930 and 1932. His two fights with Joe Louis in 1936 and 1938 were worldwide cul ...

, one of many sculptures commissioned for the grounds of the Olympic Stadium

''Olympic Stadium'' is the name usually given to the main stadium of an Olympic Games. An Olympic stadium is the site of the opening and closing ceremonies. Many, though not all, of these venues actually contain the words ''Olympic Stadium'' as ...

in Berlin.

* 1937: ''Familie'' (The Family) and ''Kameradschaft'' (Comradeship): 23-foot-tall figural groups outside the German pavilion at the Paris World's Fair, the latter consisting of two nude males clasping hands and standing defiantly side by side in a pose of racial camaraderie.Richard Overy

Richard James Overy (born 23 December 1947) is a British historian who has published on the history of World War II and Nazi Germany. In 2007, as ''The Times'' editor of ''Complete History of the World'', he chose the 50 key dates of world his ...

, ''The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia'', , p. 260.

* 1937–43: ''Goddess of Victory'' sculptural group for the Nazi party rally grounds

The Nazi party rally grounds (german: Reichsparteitagsgelände, literally: ''Reich Party Congress Grounds'') covered about 11 square kilometres in the southeast of Nuremberg, Germany. Six Nuremberg Rally, Nazi party rallies were held there betwe ...

at Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

, unfinished

* 1940: ''Der königliche Reiter'' (The Royal Rider), model for an equestrian monument to Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Sil ...

in Linz

Linz ( , ; cs, Linec) is the capital of Upper Austria and third-largest city in Austria. In the north of the country, it is on the Danube south of the Czech border. In 2018, the population was 204,846.

In 2009, it was a European Capital of ...

, exhibited in 1943

* 1941: ''Couple''

* 1942: ''Letzter Flug'' (Last Flight), wartime sculpture of a woman holding a dead soldier

* ''The Judgement of Paris'', for a fountain.

* 1943: ''Paracelsus'', commissioned for Salzburg

* 1943: ''Copernicus'', also in Salzburg

* ''Denkmal der Arbeit'' (Monument to Work), for the Reichsautobahn

The ''Reichsautobahn'' system was the beginning of the German autobahns under Nazi Germany. There had been previous plans for controlled-access highways in Germany under the Weimar Republic, and two had been constructed, but work had yet to st ...

: model exhibited in 1938–39, work unfinished. A group of workers (variously described as three, four, or five), high, straining to move a boulder.Adam, p. 194.

* 1949: ''Pietà'', St. Peter's Cemetery, Salzburg, now over his grave

Reich Chancellery striding horses

In 1939 Thorak sculpted three oversize horses ( high) for the Nuremberg rally grounds."Putzkraft gesucht, halbtags"

In 1939 Thorak sculpted three oversize horses ( high) for the Nuremberg rally grounds."Putzkraft gesucht, halbtags"''

Süddeutsche Zeitung

The ''Süddeutsche Zeitung'' (; ), published in Munich, Bavaria, is one of the largest daily newspapers in Germany. The tone of SZ is mainly described as centre-left, liberal, social-liberal, progressive-liberal, and social-democrat.

History ...

'', 23 August 2015 . Two of these, which had been placed in 1939 outside the Reich Chancellery

The Reich Chancellery (german: Reichskanzlei) was the traditional name of the office of the Chancellor of Germany (then called ''Reichskanzler'') in the period of the German Reich from 1878 to 1945. The Chancellery's seat, selected and prepared s ...

built by Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, he ...

, were discovered along with other Nazi art in a police raid

A police raid is an unexpected visit by police or other law-enforcement officers with the aim of using the element of surprise in order to seize evidence or arrest suspects believed to be likely to hide evidence, resist arrest, be politicall ...

on a storehouse in Bad Dürkheim

Bad Dürkheim () is a spa town in the Rhine-Neckar urban agglomeration, and is the seat of the Bad Dürkheim district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Geography

Location

Bad Dürkheim lies at the edge of Palatinate Forest on the German Win ...

, Rhineland-Palatinate

Rhineland-Palatinate ( , ; german: link=no, Rheinland-Pfalz ; lb, Rheinland-Pfalz ; pfl, Rhoilond-Palz) is a western state of Germany. It covers and has about 4.05 million residents. It is the ninth largest and sixth most populous of the ...

, in May 2015. The two horses had been removed in 1989 from a barracks ground in Eberswalde

Eberswalde () is a major town and the administrative seat of the district Barnim in the German State ( Bundesland / ''federated state'') of Brandenburg, about 50 km northeast of Berlin. Population 42,144 (census in June 2005), geographic ...

, northeast of Berlin, at the time in East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

, where they had sat since sometime after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.''

Der Tagesspiegel

''Der Tagesspiegel'' (meaning ''The Daily Mirror'') is a German daily newspaper. It has regional correspondent offices in Washington D.C. and Potsdam. It is the only major newspaper in the capital to have increased its circulation, now 148,000, s ...

'', 14 December 2015 ."Nazi propaganda horse winds up at German school"

''

Deutsche Welle

Deutsche Welle (; "German Wave" in English), abbreviated to DW, is a German public, state-owned international broadcaster funded by the German federal tax budget. The service is available in 32 languages. DW's satellite television service con ...

'', 12 August 2015. The third Thorak horse was displayed in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst

The ''Haus der Kunst'' (, ''House of Art'') is a non-collecting modern and contemporary art museum in Munich, Germany. It is located at Prinzregentenstraße 1 at the southern edge of the Englischer Garten, Munich's largest park.

History

Na ...

in Munich as part of the ''Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung

The Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German Art Exhibition) was held a total of eight times from 1937 to 1944 in the purpose-built Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Munich. It was representative of art under National Socialism.

History

The ...

'' (Great German Art Exhibition) in 1939, then stood outside Thorak's studio. In August 2015, it was rediscovered on the grounds of a boarding school in Ising Ising is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Ernst Ising (1900–1998), German physicist

* Gustav Ising (1883–1960), Swedish accelerator physicist

* Rudolf Ising, animator for ''MGM'', together with Hugh Harman often credited ...

, Bavaria, , having been donated to the school by Thorak's widow in 1961 in lieu of tuition fees for her son.

Honours

Thorak received the grand prize of thePrussian Academy of Arts

The Prussian Academy of Arts (German: ''Preußische Akademie der Künste'') was a state arts academy first established in Berlin, Brandenburg, in 1694/1696 by prince-elector Frederick III, in personal union Duke Frederick I of Prussia, and late ...

in 1928 and a golden Papal medal in 1934 for his contribution to the Exhibition for International Christian Art. He was nominated in 1937 for the first German National Prize for Art and Science

Through statutes of 30 January 1937, the German National Order for Art and Science (german: Der Deutscher Nationalorden für Kunst und Wissenschaft) was an award created by Adolf Hitler as a replacement for the Nobel Prize (he had forbidden German ...

. A street was named for him in Salzburg in 1963.

Ustka

Ustka (pronounced ; csb, Ùskô; german: Stolpmünde) is a spa town in the Middle Pomerania region of northern Poland with 17,100 inhabitants (2001). It is part of Słupsk County in Pomeranian Voivodeship. It is located on the Slovincian Coast on ...

File:Josef Thorak-Heim 1928 -Mutter Erde fec.jpg, ''Home'' (1928) Charlottenburg

Charlottenburg () is a Boroughs and localities of Berlin, locality of Berlin within the borough of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf. Established as a German town law, town in 1705 and named after Sophia Charlotte of Hanover, Queen consort of Kingdom ...

File:Thorak letzte flug postcard 1.jpg, ''Last Flight'' (1942), exhibition postcard

File:Paracelsus-Denkmal.JPG, ''Paracelsus'' (1943) Salzburg

Salzburg (, ; literally "Salt-Castle"; bar, Soizbuag, label=Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian) is the List of cities and towns in Austria, fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020, it had a population of 156,872.

The town is on the site of the ...

File:Crypt 25 (Petersfriedhof Salzburg) Thorak - main monument.jpg, ''Pietà'' (1949) and grave, Salzburg

See also

*Nazi art

The Nazi Germany, Nazi regime in Germany actively promoted and censored forms of art between 1933 and 1945. Upon becoming dictator in 1933, Adolf Hitler gave his personal artistic preference the force of law to a degree rarely known before. In th ...

* Nazi architecture

Nazi architecture is the architecture promoted by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime from 1933 until its fall in 1945, connected with urban planning in Nazi Germany. It is characterized by three forms: a stripped neoclassicism, typified by the ...

References

External links

*Works by Josef Thorak

''Third Reich in Ruins'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Thorak, Josef 1889 births 1952 deaths Artists from Salzburg Austrian sculptors Austrian male sculptors German sculptors German male sculptors Nazi architecture 20th-century sculptors Olympic competitors in art competitions