Jong Zuid Afrika on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Afrikaner Broederbond (AB) or simply the Broederbond was an exclusively

The chairmen of the Broederbond were:

The chairmen of the Broederbond were:

On the Afrikaner youth today and the Broederbond crutch

– Afrikaans

Membership numbers 6800 to 12000 with 450 branches

on the formation of new Afrikanerbond. * Dr JS Gericke/Kosie Gericke Vice-Chancellor Stellenbosch University {{Authority control Organizations established in 1918 1918 establishments in South Africa African secret societies Society of South Africa Apartheid in South Africa Defunct civic and political organisations in South Africa Organisations associated with apartheid Afrikaner nationalism Afrikaner organizations Anti-Catholicism in South Africa

Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a South African ethnic group descended from Free Burghers, predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: ...

Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

and male secret society in South Africa dedicated to the advancement of the Afrikaner people

Afrikaners () are a South African ethnic group descended from Free Burghers, predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: ...

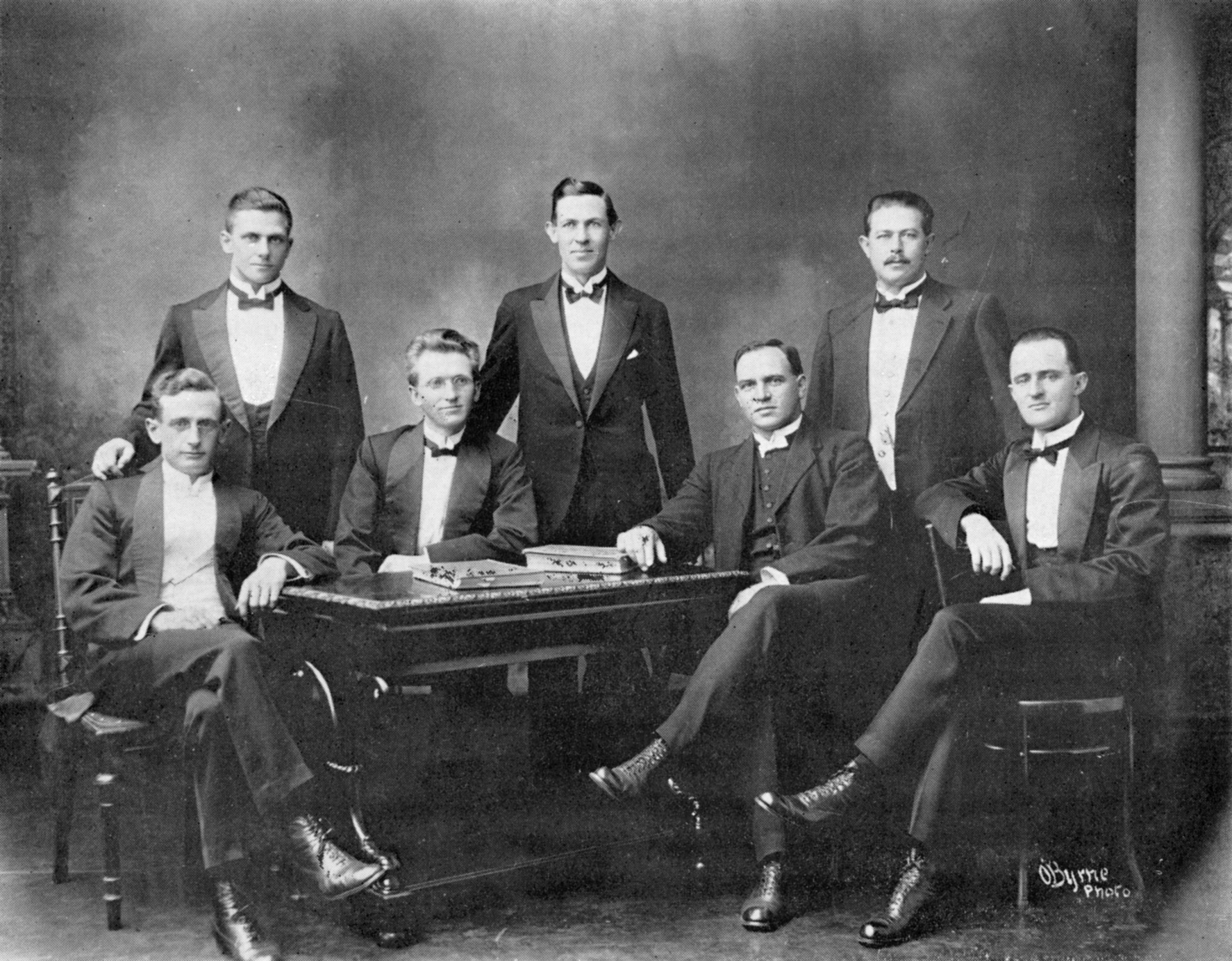

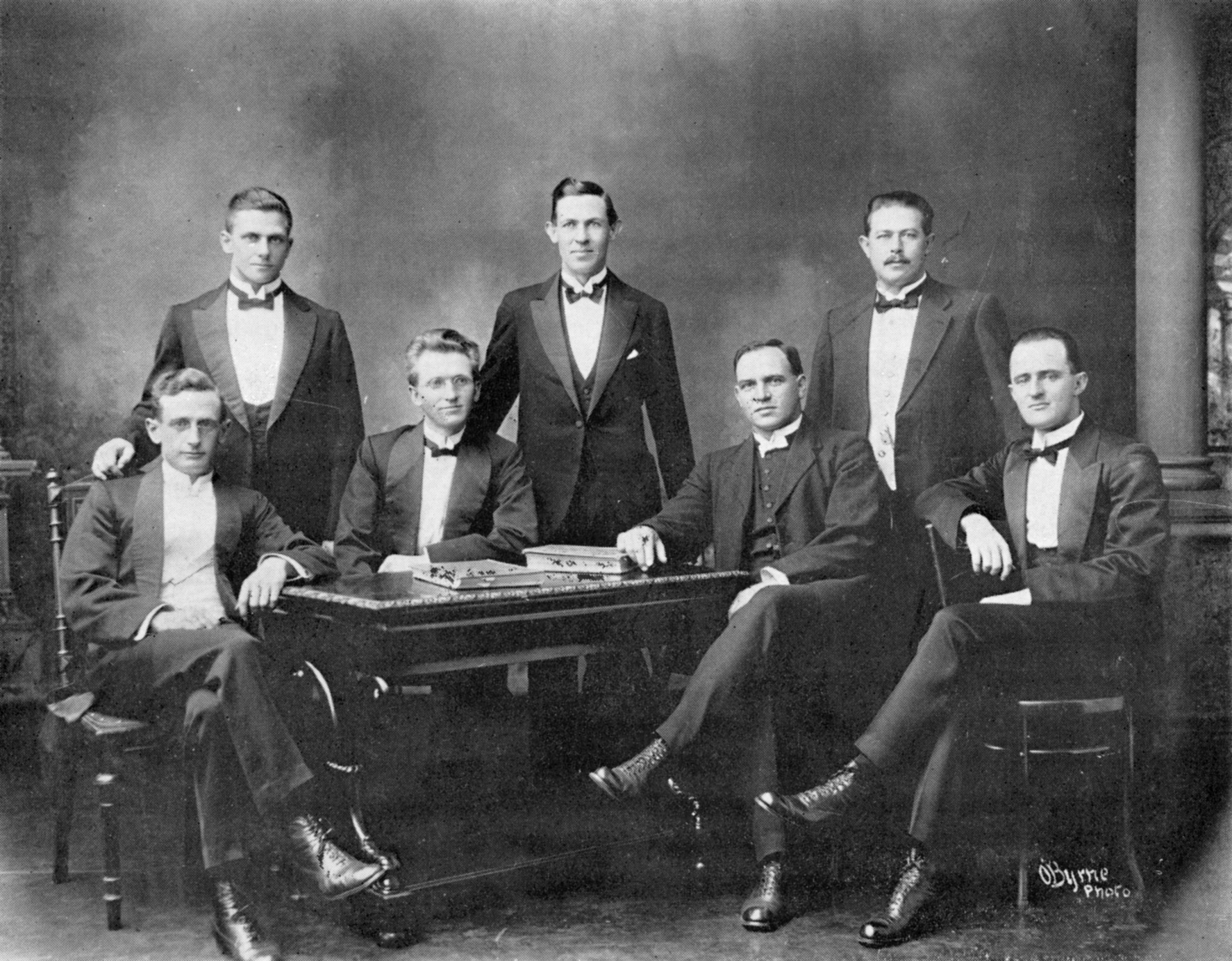

. It was founded by H. J. Klopper, H. W. van der Merwe, D. H. C. du Plessis and the Rev. Jozua Naudé in 1918 as Jong Zuid Afrika ( nl, Young South Africa) until 1920, when it was renamed the Broederbond. Its influence within South African political and social life came to a climax with the 1948-1994 rule of the white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other Race (human classification), races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any Power (social and polit ...

National Party and its policy of apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

, which was largely developed and implemented by Broederbond members. Between 1948 and 1994, many prominent figures of Afrikaner political, cultural, and religious life, including every leader of the South African government, were members of the Afrikaner Broederbond.

Origins

Described later as an "inner sanctum", "an immense informal network of influence", and byJan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

as a "dangerous, cunning, political fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

organization", in 1920 ''Jong Zuid Afrika'', now restyled as the Afrikaner Broederbond, was a group of 37 white men of Afrikaner ethnicity, Afrikaans language, and Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

faith, who shared cultural, semi-religious, and deeply political objectives based on traditions and experiences dating back to the arrival of Dutch white settlers, French Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss politica ...

, and German settlers at the Cape

A cape is a clothing accessory or a sleeveless outer garment which drapes the wearer's back, arms, and chest, and connects at the neck.

History

Capes were common in medieval Europe, especially when combined with a hood in the chaperon. Th ...

in the 17th and 18th centuries, and including the dramatic events of the Great Trek

The Great Trek ( af, Die Groot Trek; nl, De Grote Trek) was a Northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyon ...

in the 1830s and 1840s. Ivor Wilkins and Hans Strydom recount how, on the occasion of its 50th anniversary, a leading ''broeder'' (brother or member) said:

The precise intentions of the founders are not clear. Some considered that the group was intended to counter the dominance of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

and the English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the is ...

, whilst others considered that the purpose was to redeem the Afrikaners after their defeat in the Second Anglo-Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

. Another view is that it sought to protect culture, build an economy and seize control of the government. The remarks of the organisation's chairman in 1944 offer a slightly different, and possibly more accurate interpretation in the context of the post-Boer War and post-World War I era, when Afrikaners were suffering through a maelstrom of social and political changes:

The Afrikaner Broederbond was born out of the deep conviction that the Afrikaners had been planted in the country by the Hand of God, destined to survive as a separate people with its own calling.

The traditional, deeply pious Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

of the Afrikaners, a pastoral

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depicts ...

people with a difficult history in South Africa since the mid-17th century, supplied an element of Christian predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby G ...

that led to a determination to wrest the country from the English-speaking population of British descent and place its future in the hands of the Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gra ...

-speaking Afrikaners, whatever that might mean for the large black and coloured population. To the old thirst for sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

that had prompted the Great Trek

The Great Trek ( af, Die Groot Trek; nl, De Grote Trek) was a Northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyon ...

into the interior from 1838 on, would be added a new thirst for total independence and nationalism. These two threads merged to form a "Christian National" civil religion

Civil religion, also referred to as a civic religion, is the implicit religious values of a nation, as expressed through public rituals, symbols (such as the national flag), and ceremonies on sacred days and at sacred places (such as monuments, bat ...

that would dominate South African life from 1948 to 1994.

The emergence of the Broederbond took place amidst the backdrop of a rise in Afrikaner nationalism

Afrikaner nationalism ( af, Afrikanernasionalisme) is a nationalistic political ideology which created by Afrikaners residing in Southern Africa during the Victorian era. The ideology was developed in response to the significant events in Afrik ...

as a result of the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

(1899-1902), which saw the British annex the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it ...

and the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

. During the conflict, the British deployed scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, communi ...

tactics against the Boers, destroying Boer farms and interning captured Boer non-combatants in concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

, where roughly 27,000 Boers died. The war was brought to end by the Treaty of Vereeniging

The Treaty of Vereeniging was a peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the Second Boer War between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State, on the one side, and the United Kingdom on the other.

This settlement provided f ...

, which though generous in its terms was seen by the Boers as deeply humiliating. The anglicisation

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influen ...

policies of British administrator Lord Milner

Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, (23 March 1854 – 13 May 1925) was a British statesman and colonial administrator who played a role in the formulation of British foreign and domestic policy between the mid-1890s and early 1920s. From ...

was also a major source of resentment amongst the Afrikaners. These developments led to an increase in nationalistic sentiments amongst Afrikaners, leading to the formation of the Broederbond and the National Party.

The National Party had been established in 1914 by Afrikaner nationalists. They first came to power in 1924. Ten years later, its leader J. B. M. Hertzog

General James Barry Munnik Hertzog (3 April 1866 – 21 November 1942), better known as Barry Hertzog or J. B. M. Hertzog, was a South African politician and soldier. He was a Boer general during the Second Boer War who serve ...

and Jan Smuts of the South African Party

nl, Zuidafrikaanse Partij

, leader1_title = Leader (s)

, leader1_name = Louis Botha,Jan Smuts, Barry Hertzog

, foundation =

, dissolution =

, merger = Het VolkSouth African PartyAfrikaner BondOrangia Unie

, merged ...

merged their parties to form the United Party. This angered a contingent of hardline nationalists under D. F. Malan, who broke away to form the Purified National Party

The Purified National Party ( af, Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party) was a break away from Hertzog's National Party which lasted from 1935 to 1948

In 1935 the main portion of the National Party, led by J. B. M. Hertzog, merged with the South African P ...

. By the time World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

broke out, resentment towards the British had not subsided. Malan's party opposed South Africa's entry into the war on the side of the British; some of its members wanted to support Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. Jan Smuts had commanded British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

forces in the East African theater of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and was amenable to backing the Allies a second time. This was the spark Afrikaner nationalism needed. Hertzog, who was in favour of neutrality, resigned from the United Party when a narrow majority in his cabinet backed Smuts. He started the Afrikaner Party

The Afrikaner Party (AP) was a South African political party from 1941 to 1951.

Origins

The Afrikaner Party's roots can be traced back to September 1939, when South Africa declared war on Germany shortly after the start of World War II. The then ...

which would amalgamate later with D.F. Malan's ’'Purified National Party'’ to become the force that would take over South African politics for the next 46 years, until majority rule

Majority rule is a principle that means the decision-making power belongs to the group that has the most members. In politics, majority rule requires the deciding vote to have majority, that is, more than half the votes. It is the binary deci ...

and Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist who served as the President of South Africa, first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1 ...

's election in 1994.

The Broederbond and apartheid

Everyprime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

and state president in South Africa from 1948 to the end of apartheid in 1994 was a member of the Afrikaner Broederbond.

Once theThe Herenigde Nationale Party was the product of the reunion of the Purified National Party and the United Party in 1940. The Afrikaner Broederbond continued to act in secret, infiltrating and gaining control of the few organisations, such as the South African Agricultural Union (SAAU), which had political power and were opposed to a further escalation of apartheid policies. Members of political parties right of the National Party were not welcome and 200 members were expelled by 1972. In 1983 when theHerenigde Nasionale Party The Herenigde Nasionale Party (Reunited National Party) was a political party in South Africa during the 1940s. It was the product of the reunion of Daniel François Malan's Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party (Purified National Party) and J.B.M. Hertzo ...was in power...English-speaking bureaucrats, soldiers, and state employees were sidelined by reliable Afrikaners, with key posts going to Broederbond members (with their ideological commitment to separatism). The electoral system itself was manipulated to reduce the impact of immigrant English speakers and eliminate that of Coloureds.

Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

was founded with Andries Treurnicht

Andries Petrus Treurnicht (19 February 1921 – 22 April 1993) was a South African politician, Minister of Education during the Soweto Riots and for a short time leader of the National Party in Transvaal. In 1982 he founded and led the Conse ...

as a leader, all Broederbond members who belonged to the newly formed party were no longer welcome in the Broederbond. Treurnicht, C.W.H. Boshoff and H.J. Klopper, previous chairmen, left the organization. Other members like H. J. van den Bergh left too.

In 1985 the Afrikaner Broederbond realised that change needed to take place in South African politics. Although the government did not talk openly with the banned African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a Social democracy, social-democratic political party in Republic of South Africa, South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when ...

(ANC), it was decided by the organization they should start negotiating. On 8 June 1986 J.P. de Lange, the then-chairman met Thabo Mbeki

Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki KStJ (; born 18 June 1942) is a South African politician who was the second president of South Africa from 14 June 1999 to 24 September 2008, when he resigned at the request of his party, the African National Congress (ANC ...

in New York for a five-hour meeting held at a conference organised by the Ford Foundation. The meeting was just between de Lange and Mbeki, but at the conference other ANC members Mac Maharaj

Sathyandranath Ragunanan "Mac" Maharaj (born 22 April 1936 in Newcastle, Natal) is a retired South African politician affiliated with the African National Congress, academic and businessman of Indian origin. He was the official spokesperson ...

, Seretse Choabi, Charles Villa-Vicencio

Charles Villa-Vicencio is an Emeritus Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Cape Town. He is also a Visiting research professor at Georgetown University. He was a director of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission which organised t ...

, and Peggy Dulany were present.

P.W. Botha also left the Broederbond after his retirement.

Leaders

The chairmen of the Broederbond were:

The chairmen of the Broederbond were:

Exposed

Although the press had maintained a steady trickle of unsourced exposes of the inner workings and membership of the Broederbond since the 1960s, the first comprehensive expose of the organisation was a book written by Ivor Wilkins and Hans Strydom, ''The Super-Afrikaners. Inside the Afrikaner Broederbond'', first published in 1978. The most notable and discussed section of the book was the last section which consisted of a near-comprehensive list of 7,500 Broederbond members. The Broederbond was portrayed as ''Die Stigting Adriaan Delport'' (The Adriaan Delport Foundation) in the 1968 South African feature film '' Die Kandidaat'' (The Candidate), directed by Jans Rautenbach and produced byEmil Nofal

Emil Nofal (1926 – 18 July 1986) was a South African film director, producer and screenwriter.

Selected filmography

Director

* '' Song of Africa'' (1951)

* '' Kimberley Jim'' (1965)

* '' Wild Season'' (1967)

* ''My Way'' (1973)

* '' The S ...

.

Companies with Broederbond credentials

* ABSA, formed by an amalgamation of United, Allied, Trust and Volkskas banks, the latter of which was established by the Broederbond in 1934 and whose chairman was also the Broederbond chairman at the time. * ADS, formerly Altech Defence Systems. *Remgro

Remgro Limited is an investment holding company based in Stellenbosch, South Africa. It has interests in banking, financial services, packaging, glass products, medical services, mining, petroleum, beverage, food and personal care products. I ...

, formerly Rembrandt Ltd., former holding company of Volkskas.

Notable members

* Theunis Roux Botha, Former and last Rector of the Randse Afrikaanse Universiteit. * D. F. Malan (1874-1959), former Prime Minister (1948-1954). *H. F. Verwoerd

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd (; 8 September 1901 – 6 September 1966) was a South African politician, a scholar of Applied Psychology, applied psychology and sociology, and chief editor of ''Die Transvaler'' newspaper. He is commonly regarde ...

(1901-1966), former Prime Minister.

* J. G. Strijdom (1893-1958), former Prime Minister (1954-1958).

* B. J. Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; also known as John Vorster; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983) was a South African apartheid politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state presid ...

(1915-1983), former Prime Minister (1966-1978) and State President (1978-1979).

* J. S. Gericke, Vice-Chancellor Stellenbosch University.

* Pik Botha

Roelof Frederik "Pik" Botha, (27 April 1932 – 12 October 2018) was a South African politician who served as the country's foreign minister in the last years of the apartheid era, the longest-serving in South African history. Known as a liber ...

, former Minister of Foreign Affairs.

* H. B. Thom

Hendrik Bernardus Thom (13 December 1905 – 4 November 1983) was a British professor and former Rector of the Stellenbosch University.

Life and career

Thom was born in Jamestown, Cape Colony, and grew up in Burgersdorp, South Africa. B ...

, historian and former Rector of Stellenbosch University

Stellenbosch University ( af, Universiteit Stellenbosch) is a public research university situated in Stellenbosch, a town in the Western Cape province of South Africa. Stellenbosch is the oldest university in South Africa and the oldest extant ...

.

* G.L.P. Moerdijk, Afrikaans architect best known for designing the Voortrekker Monument

The Voortrekker Monument is located just south of Pretoria in South Africa. The granite structure is located on a hilltop, and was raised to commemorate the Voortrekkers who left the Cape Colony between 1835 and 1854. It was designed by the a ...

in Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends ...

.

* Tienie Groenewald, retired Defence Force general.

* Barend Johannes van der Walt, former ambassador to Canada.

* Pieter Johannes Potgieter Stofberg, former politician, billionaire businessman and famous doctor.

* P. W. Botha

Pieter Willem Botha, (; 12 January 1916 – 31 October 2006), commonly known as P. W. and af, Die Groot Krokodil (The Big Crocodile), was a South African politician. He served as the last prime minister of South Africa from 1978 to 1984 and ...

, former Minister of Defence and Prime Minister. He left the Broederbond.

* Anton Rupert

Anthony Edward Rupert (4 October 1916 – 18 January 2006) was a South African businessman, philanthropist, and conservationist.

He was born and raised in the small town of Graaff-Reinet in the Eastern Cape. He studied in Pretoria and ultimat ...

, billionaire entrepreneur and businessman; a member in the 1940s, but eventually dismissed it as an "absurdity" and left the organization.

* Marthinus van Schalkwyk, a former member of the youth wing of the Broederbond, the last leader of the National Party and former minister of tourism in the ANC

The African National Congress (ANC) is a social-democratic political party in South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election install ...

government of Jacob Zuma

Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma (; born 12 April 1942) is a South African politician who served as the fourth president of South Africa from 2009 to 2018. He is also referred to by his initials JZ and clan name Msholozi, and was a former anti-aparth ...

.

* Tom de Beer, recruited 30 years ago, now chairman of new Afrikanerbond.

* Nico Smith

Nico Smith (''Nicolaas Johannes Smith''; 1929 – 19 June 2010) was a South African Afrikaner minister and prominent opponent of apartheid. Smith was a professor of theology at the University of Stellenbosch, a member of the Afrikaner Broederb ...

, Dutch Reformed Church missionary who, as a former insider, wrote retrospectively about the Afrikaner Broederbond in a book.Smith, N. (2009) Afrikaner Broederbond: Belewings van die binnekant. Lapa Uitgewers. Pretoria

* F. W. De Klerk, former South African State President and leader of the National Party.

* "Lang" Hendrik van den Bergh, the South African head of state security apparatus during the Apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

regime, and close friend of former South African Prime Minister B. J. Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; also known as John Vorster; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983) was a South African apartheid politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state presid ...

. He left the Bond.

References

Further reading

On the Afrikaner youth today and the Broederbond crutch

– Afrikaans

Membership numbers 6800 to 12000 with 450 branches

on the formation of new Afrikanerbond. * Dr JS Gericke/Kosie Gericke Vice-Chancellor Stellenbosch University {{Authority control Organizations established in 1918 1918 establishments in South Africa African secret societies Society of South Africa Apartheid in South Africa Defunct civic and political organisations in South Africa Organisations associated with apartheid Afrikaner nationalism Afrikaner organizations Anti-Catholicism in South Africa