Johnson, Samuel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and

Samuel Johnson was born on 18 September 1709, to Sarah (née Ford) and Michael Johnson, a bookseller. His mother was 40 when she gave birth to Johnson in the family home above his father's bookshop in

Samuel Johnson was born on 18 September 1709, to Sarah (née Ford) and Michael Johnson, a bookseller. His mother was 40 when she gave birth to Johnson in the family home above his father's bookshop in  During this time, Johnson's future remained uncertain because his father was deeply in debt. To earn money, Johnson began to stitch books for his father, and it is likely that Johnson spent much time in his father's bookshop reading and building his literary knowledge. The family remained in poverty until his mother's cousin Elizabeth Harriotts died in February 1728 and left enough money to send Johnson to university. On 31 October 1728, a few weeks after he turned 19, Johnson entered Pembroke College, Oxford. The inheritance did not cover all of his expenses at Pembroke, and Andrew Corbet, a friend and fellow student at the college, offered to make up the deficit.

Johnson made friends at Pembroke and read much. His tutor asked him to produce a Latin translation of

During this time, Johnson's future remained uncertain because his father was deeply in debt. To earn money, Johnson began to stitch books for his father, and it is likely that Johnson spent much time in his father's bookshop reading and building his literary knowledge. The family remained in poverty until his mother's cousin Elizabeth Harriotts died in February 1728 and left enough money to send Johnson to university. On 31 October 1728, a few weeks after he turned 19, Johnson entered Pembroke College, Oxford. The inheritance did not cover all of his expenses at Pembroke, and Andrew Corbet, a friend and fellow student at the college, offered to make up the deficit.

Johnson made friends at Pembroke and read much. His tutor asked him to produce a Latin translation of

Johnson continued to look for a position at a Lichfield school. After being turned down for a job at Ashbourne School, he spent time with his friend Edmund Hector, who was living in the home of the publisher

Johnson continued to look for a position at a Lichfield school. After being turned down for a job at Ashbourne School, he spent time with his friend Edmund Hector, who was living in the home of the publisher  In June 1735, while working as a tutor for the children of Thomas Whitby, a local Staffordshire gentleman, Johnson had applied for the position of headmaster at

In June 1735, while working as a tutor for the children of Thomas Whitby, a local Staffordshire gentleman, Johnson had applied for the position of headmaster at  In May 1738 his first major work, the poem ''

In May 1738 his first major work, the poem ''

In preparation, Johnson had written a ''Plan'' for the ''Dictionary''.

In preparation, Johnson had written a ''Plan'' for the ''Dictionary''.

On 16 March 1756, Johnson was arrested for an outstanding debt of £5 18 s. Unable to contact anyone else, he wrote to the writer and publisher Samuel Richardson. Richardson, who had previously lent Johnson money, sent him six

On 16 March 1756, Johnson was arrested for an outstanding debt of £5 18 s. Unable to contact anyone else, he wrote to the writer and publisher Samuel Richardson. Richardson, who had previously lent Johnson money, sent him six

On 6 August 1773, eleven years after first meeting Boswell, Johnson set out to visit his friend in Scotland, and to begin "a journey to the western islands of Scotland", as Johnson's 1775 account of their travels would put it. That account was intended to discuss the social problems and struggles that affected the Scottish people, but it also praised many of the unique facets of Scottish society, such as a school in Edinburgh for the deaf and mute. Also, Johnson used the work to enter into the dispute over the authenticity of James Macpherson's Ossian poems, claiming they could not have been translations of ancient Scottish literature on the grounds that "in those times nothing had been written in the Earse .e. Scots Gaeliclanguage". There were heated exchanges between the two, and according to one of Johnson's letters, MacPherson threatened physical violence. Boswell's account of their journey, '' The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides'' (1786), was a preliminary step toward his later biography, '' The Life of Samuel Johnson''. Included were various quotations and descriptions of events, including anecdotes such as Johnson swinging a

On 6 August 1773, eleven years after first meeting Boswell, Johnson set out to visit his friend in Scotland, and to begin "a journey to the western islands of Scotland", as Johnson's 1775 account of their travels would put it. That account was intended to discuss the social problems and struggles that affected the Scottish people, but it also praised many of the unique facets of Scottish society, such as a school in Edinburgh for the deaf and mute. Also, Johnson used the work to enter into the dispute over the authenticity of James Macpherson's Ossian poems, claiming they could not have been translations of ancient Scottish literature on the grounds that "in those times nothing had been written in the Earse .e. Scots Gaeliclanguage". There were heated exchanges between the two, and according to one of Johnson's letters, MacPherson threatened physical violence. Boswell's account of their journey, '' The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides'' (1786), was a preliminary step toward his later biography, '' The Life of Samuel Johnson''. Included were various quotations and descriptions of events, including anecdotes such as Johnson swinging a

Although he had recovered his health by August, Johnson experienced emotional trauma when he was given word that Hester Thrale would sell the residence that Johnson shared with the family. What hurt Johnson most was the possibility that he would be left without her constant company. Months later, on 6 October 1782, Johnson attended church for the final time in his life, to say goodbye to his former residence and life. The walk to the church strained him, but he managed the journey unaccompanied. While there, he wrote a prayer for the Thrale family:

Hester Thrale did not completely abandon Johnson, and asked him to accompany the family on a trip to Brighton. He agreed, and was with them from 7 October to 20 November 1782. On his return, his health began to fail, and he was left alone after Boswell's visit on 29 May 1783.

On 17 June 1783, Johnson's poor circulation resulted in a stroke and he wrote to his neighbour, Edmund Allen, that he had lost the ability to speak. Two doctors were brought in to aid Johnson; he regained his ability to speak two days later. Johnson feared that he was dying, and wrote:

By this time he was sick and gout-ridden. He had surgery for gout, and his remaining friends, including novelist

Although he had recovered his health by August, Johnson experienced emotional trauma when he was given word that Hester Thrale would sell the residence that Johnson shared with the family. What hurt Johnson most was the possibility that he would be left without her constant company. Months later, on 6 October 1782, Johnson attended church for the final time in his life, to say goodbye to his former residence and life. The walk to the church strained him, but he managed the journey unaccompanied. While there, he wrote a prayer for the Thrale family:

Hester Thrale did not completely abandon Johnson, and asked him to accompany the family on a trip to Brighton. He agreed, and was with them from 7 October to 20 November 1782. On his return, his health began to fail, and he was left alone after Boswell's visit on 29 May 1783.

On 17 June 1783, Johnson's poor circulation resulted in a stroke and he wrote to his neighbour, Edmund Allen, that he had lost the ability to speak. Two doctors were brought in to aid Johnson; he regained his ability to speak two days later. Johnson feared that he was dying, and wrote:

By this time he was sick and gout-ridden. He had surgery for gout, and his remaining friends, including novelist

Johnson's tall and robust figure combined with his odd gestures were confusing to some; when

Johnson's tall and robust figure combined with his odd gestures were confusing to some; when

There are many accounts of Johnson suffering from bouts of depression and what Johnson thought might be madness. As Walter Jackson Bate puts it, "one of the ironies of literary history is that its most compelling and authoritative symbol of common sense—of the strong, imaginative grasp of concrete reality—should have begun his adult life, at the age of twenty, in a state of such intense anxiety and bewildered despair that, at least from his own point of view, it seemed the onset of actual insanity". To overcome these feelings, Johnson tried to constantly involve himself with various activities, but this did not seem to help. Taylor said that Johnson "at one time strongly entertained thoughts of suicide". Boswell claimed that Johnson "felt himself overwhelmed with an horrible melancholia, with perpetual irritation, fretfulness, and impatience; and with a dejection, gloom, and despair, which made existence misery".

Early on, when Johnson was unable to pay off his debts, he began to work with professional writers and identified his own situation with theirs. During this time, Johnson witnessed Christopher Smart's decline into "penury and the madhouse", and feared that he might share the same fate. Hester Thrale Piozzi claimed, in a discussion on Smart's mental state, that Johnson was her "friend who feared an apple should intoxicate him". To her, what separated Johnson from others who were placed in asylums for madness—like Christopher Smart—was his ability to keep his concerns and emotions to himself.

Two hundred years after Johnson's death, the posthumous diagnosis of Tourette syndrome became widely accepted. The condition was unknown during Johnson's lifetime, but Boswell describes Johnson displaying signs of Tourette syndrome, including

There are many accounts of Johnson suffering from bouts of depression and what Johnson thought might be madness. As Walter Jackson Bate puts it, "one of the ironies of literary history is that its most compelling and authoritative symbol of common sense—of the strong, imaginative grasp of concrete reality—should have begun his adult life, at the age of twenty, in a state of such intense anxiety and bewildered despair that, at least from his own point of view, it seemed the onset of actual insanity". To overcome these feelings, Johnson tried to constantly involve himself with various activities, but this did not seem to help. Taylor said that Johnson "at one time strongly entertained thoughts of suicide". Boswell claimed that Johnson "felt himself overwhelmed with an horrible melancholia, with perpetual irritation, fretfulness, and impatience; and with a dejection, gloom, and despair, which made existence misery".

Early on, when Johnson was unable to pay off his debts, he began to work with professional writers and identified his own situation with theirs. During this time, Johnson witnessed Christopher Smart's decline into "penury and the madhouse", and feared that he might share the same fate. Hester Thrale Piozzi claimed, in a discussion on Smart's mental state, that Johnson was her "friend who feared an apple should intoxicate him". To her, what separated Johnson from others who were placed in asylums for madness—like Christopher Smart—was his ability to keep his concerns and emotions to himself.

Two hundred years after Johnson's death, the posthumous diagnosis of Tourette syndrome became widely accepted. The condition was unknown during Johnson's lifetime, but Boswell describes Johnson displaying signs of Tourette syndrome, including

Johnson was, in the words of Steven Lynn, "more than a well-known writer and scholar"; he was a celebrity, for the activities and the state of his health in his later years were constantly reported in various journals and newspapers, and when there was nothing to report, something was invented. According to Bate, "Johnson loved biography," and he "changed the whole course of biography for the modern world. One by-product was the most famous single work of biographical art in the whole of literature, Boswell's ''Life of Johnson'', and there were many other memoirs and biographies of a similar kind written on Johnson after his death." These accounts of his life include Thomas Tyers's ''

Johnson was, in the words of Steven Lynn, "more than a well-known writer and scholar"; he was a celebrity, for the activities and the state of his health in his later years were constantly reported in various journals and newspapers, and when there was nothing to report, something was invented. According to Bate, "Johnson loved biography," and he "changed the whole course of biography for the modern world. One by-product was the most famous single work of biographical art in the whole of literature, Boswell's ''Life of Johnson'', and there were many other memoirs and biographies of a similar kind written on Johnson after his death." These accounts of his life include Thomas Tyers's ''

Samuel Johnson's Dictionary Online

Samuel Johnson

at th

Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

Samuel Johnson and Hodge his Cat

Full text of Johnson's essays

arranged chronologically * BBC Radio 4 audio program

''In Our Time''

an

''Great Lives''

A Monument More Durable Than Brass: The Donald and Mary Hyde Collection of Dr. Samuel Johnson

nbsp;– online exhibition from

The Samuel Johnson Sound Bite Page

comprehensive collection of quotations

Samuel Johnson

at the National Portrait Gallery, London * by

lexicographer

Lexicography is the study of lexicons, and is divided into two separate academic disciplines. It is the art of compiling dictionaries.

* Practical lexicography is the art or craft of compiling, writing and editing dictionaries.

* Theoretica ...

. The ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' calls him "arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history".

Born in Lichfield

Lichfield () is a cathedral city and civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated roughly south-east of the county town of Stafford, south-east of Rugeley, north-east of Walsall, north-west of Tamworth and south-west o ...

, Staffordshire, he attended Pembroke College, Oxford until lack of funds forced him to leave. After working as a teacher, he moved to London and began writing for ''The Gentleman's Magazine

''The Gentleman's Magazine'' was a monthly magazine founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term '' magazine'' (from the French ''magazine ...

''. Early works include ''Life of Mr Richard Savage

Samuel Johnson's ''Life of Mr Richard Savage'' (1744), short title ''Life of Savage'' and full title ''An Account of the Life of Mr Richard Savage, Son of the Earl Rivers'', was the first major biography published by Johnson. It was released an ...

'', the poems ''London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

'' and ''The Vanity of Human Wishes

''The Vanity of Human Wishes: The Tenth Satire of Juvenal Imitated'' is a poem by the English author Samuel Johnson. It was written in late 1748 and published in 1749 (see 1749 in poetry). It was begun and completed while Johnson was busy writ ...

'' and the play ''Irene

Irene is a name derived from εἰρήνη (eirēnē), the Greek for "peace".

Irene, and related names, may refer to:

* Irene (given name)

Places

* Irene, Gauteng, South Africa

* Irene, South Dakota, United States

* Irene, Texas, United Stat ...

''. After nine years' effort, Johnson's '' A Dictionary of the English Language'' appeared in 1755, and was acclaimed as "one of the greatest single achievements of scholarship". Later work included essays, an annotated ''The Plays of William Shakespeare

''The Plays of William Shakespeare'' was an 18th-century edition of the dramatic works of William Shakespeare, edited by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens. Johnson announced his intention to edit Shakespeare's plays in his ''Miscellaneous O ...

'', and the apologue ''The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia

''The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia'', originally titled ''The Prince of Abissinia: A Tale'', though often abbreviated to ''Rasselas'', is an apologue about bliss and ignorance by Samuel Johnson. The book's original working title was " ...

''. In 1763 he befriended James Boswell, with whom he travelled to Scotland, as Johnson described in '' A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland''. Near the end of his life came a massive, influential ''Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets

''Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets'' (1779–81), alternatively known by the shorter title ''Lives of the Poets'', is a work by Samuel Johnson comprising short biographies and critical appraisals of 52 poets, most of whom lived during th ...

'' of the 17th and 18th centuries.

He was a devout Anglican, and a committed Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

. Tall and robust, he displayed gestures and tic

A tic is a sudden, repetitive, nonrhythmic motor movement or vocalization involving discrete muscle groups.American Psychiatric Association (2000)DSM-IV-TR: Tourette's Disorder.''Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders'', 4th ed., ...

s that disconcerted some on meeting him. Boswell's ''Life'', along with other biographies, documented Johnson's behaviour and mannerisms in such detail that they have informed the posthumous diagnosis

A retrospective diagnosis (also retrodiagnosis or posthumous diagnosis) is the practice of identifying an illness after the death of the patient (sometimes in a historical figure) using modern knowledge, methods and disease classifications. Altern ...

of Tourette syndrome

Tourette syndrome or Tourette's syndrome (abbreviated as TS or Tourette's) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder that begins in childhood or adolescence. It is characterized by multiple movement (motor) tics and at least one vocal (phonic) ...

, and a condition not defined or diagnosed in the 18th century. After several illnesses, he died on the evening of 13 December 1784 and was buried in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the Unite ...

.

In his later life Johnson became a celebrity, and following his death he was increasingly seen to have had a lasting effect on literary criticism, even being claimed to be the one truly great critic of English literature. A prevailing mode of literary theory in the 20th century drew from his views, and he had a lasting impact on biography

A biography, or simply bio, is a detailed description of a person's life. It involves more than just the basic facts like education, work, relationships, and death; it portrays a person's experience of these life events. Unlike a profile or ...

. Johnson's ''Dictionary'' had far-reaching effects on Modern English, and was pre-eminent until the arrival of the ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a co ...

'' 150 years later. James Boswell

James Boswell, 9th Laird of Auchinleck (; 29 October 1740 ( N.S.) – 19 May 1795), was a Scottish biographer, diarist, and lawyer, born in Edinburgh. He is best known for his biography of his friend and older contemporary the English writer ...

's ''Life of Samuel Johnson

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energy tran ...

'' was selected by Johnson biographer Walter Jackson Bate

Walter Jackson Bate (May 23, 1918 – July 26, 1999) was an American literary critic and biographer. He is known for Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography-winning biographies of Samuel Johnson (1978) and John Keats (1964).

as "the most famous single work of biographical art in the whole of literature".

Life and career

Early life and education

Samuel Johnson was born on 18 September 1709, to Sarah (née Ford) and Michael Johnson, a bookseller. His mother was 40 when she gave birth to Johnson in the family home above his father's bookshop in

Samuel Johnson was born on 18 September 1709, to Sarah (née Ford) and Michael Johnson, a bookseller. His mother was 40 when she gave birth to Johnson in the family home above his father's bookshop in Lichfield

Lichfield () is a cathedral city and civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated roughly south-east of the county town of Stafford, south-east of Rugeley, north-east of Walsall, north-west of Tamworth and south-west o ...

, Staffordshire. This was considered an unusually late pregnancy, so precautions were taken, and a man-midwife and surgeon of "great reputation" named George Hector was brought in to assist. The infant Johnson did not cry, and there were concerns for his health. His aunt exclaimed that "she would not have picked such a poor creature up in the street". The family feared that Johnson would not survive, and summoned the vicar of St Mary's to perform a baptism. Two godfathers were chosen, Samuel Swynfen, a physician and graduate of Pembroke College, Oxford, and Richard Wakefield, a lawyer, coroner and Lichfield town clerk.

Johnson's health improved and he was put to wet-nurse

A wet nurse is a woman who breastfeeds and cares for another's child. Wet nurses are employed if the mother dies, or if she is unable or chooses not to nurse the child herself. Wet-nursed children may be known as "milk-siblings", and in some cu ...

with Joan Marklew. Some time later he contracted scrofula, known at the time as the "King's Evil" because it was thought royalty could cure it. Sir John Floyer, former physician to King Charles II, recommended that the young Johnson should receive the "royal touch

The royal touch (also known as the king's touch) was a form of laying on of hands, whereby French and English monarchs touched their subjects, regardless of social classes, with the intent to cure them of various diseases and conditions. The ...

", and he did so from Queen Anne on 30 March 1712. However, the ritual proved ineffective, and an operation was performed that left him with permanent scars across his face and body. Queen Anne gave Johnson an amulet on a chain he would wear the rest of his life.

When Johnson was three, Nathaniel was born. According to Nathaniel, in a letter he wrote to Sarah, complained Johnson "would scarcely ever use me with common civility." With the birth of Johnson's brother their father was unable to pay the debts he had accrued over the years, and the family was no longer able to maintain its standard of living.

Johnson displayed signs of great intelligence as a child, and his parents, to his later disgust, would show off his "newly acquired accomplishments". His education began at the age of three, and was provided by his mother, who had him memorise and recite passages from the ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

''. When Samuel turned four, he was sent to a nearby school, and, at the age of six he was sent to a retired shoemaker to continue his education. A year later Johnson went to Lichfield Grammar School

Lichfield () is a cathedral city and civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated roughly south-east of the county town of Stafford, south-east of Rugeley, north-east of Walsall, north-west of Tamworth and south-west of ...

, where he excelled in Latin. For his most personal poems, Johnson used Latin. During this time, Johnson started to exhibit the tic

A tic is a sudden, repetitive, nonrhythmic motor movement or vocalization involving discrete muscle groups.American Psychiatric Association (2000)DSM-IV-TR: Tourette's Disorder.''Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders'', 4th ed., ...

s that would influence how people viewed him in his later years, and which formed the basis for a posthumous diagnosis of Tourette syndrome

Tourette syndrome or Tourette's syndrome (abbreviated as TS or Tourette's) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder that begins in childhood or adolescence. It is characterized by multiple movement (motor) tics and at least one vocal (phonic) ...

. He excelled at his studies and was promoted to the upper school at the age of nine. During this time, he befriended Edmund Hector, nephew of his "man-midwife" George Hector, and John Taylor, with whom he remained in contact for the rest of his life.

At the age of 16, Johnson stayed with his cousins, the Fords, at Pedmore

Pedmore is a residential suburb of Stourbridge in the West Midlands of England. It was originally a village in the Worcestershire countryside until extensive housebuilding during the interwar years saw it gradually merged into Stourbridge. The po ...

, Worcestershire. There he became a close friend of Cornelius Ford, who employed his knowledge of the classics to tutor Johnson while he was not attending school. Ford was a successful, well-connected academic, and notorious alcoholic whose excesses contributed to his death six years later. After spending six months with his cousins, Johnson returned to Lichfield, but Hunter, the headmaster, "angered by the impertinence of this long absence", refused to allow Johnson to continue at the school. Unable to return to Lichfield Grammar School, Johnson enrolled at the King Edward VI grammar school at Stourbridge

Stourbridge is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley in the West Midlands, England, situated on the River Stour. Historically in Worcestershire, it was the centre of British glass making during the Industrial Revolution. The ...

. As the school was located near Pedmore, Johnson was able to spend more time with the Fords, and he began to write poems and verse translations. However, he spent only six months at Stourbridge before returning once again to his parents' home in Lichfield.

During this time, Johnson's future remained uncertain because his father was deeply in debt. To earn money, Johnson began to stitch books for his father, and it is likely that Johnson spent much time in his father's bookshop reading and building his literary knowledge. The family remained in poverty until his mother's cousin Elizabeth Harriotts died in February 1728 and left enough money to send Johnson to university. On 31 October 1728, a few weeks after he turned 19, Johnson entered Pembroke College, Oxford. The inheritance did not cover all of his expenses at Pembroke, and Andrew Corbet, a friend and fellow student at the college, offered to make up the deficit.

Johnson made friends at Pembroke and read much. His tutor asked him to produce a Latin translation of

During this time, Johnson's future remained uncertain because his father was deeply in debt. To earn money, Johnson began to stitch books for his father, and it is likely that Johnson spent much time in his father's bookshop reading and building his literary knowledge. The family remained in poverty until his mother's cousin Elizabeth Harriotts died in February 1728 and left enough money to send Johnson to university. On 31 October 1728, a few weeks after he turned 19, Johnson entered Pembroke College, Oxford. The inheritance did not cover all of his expenses at Pembroke, and Andrew Corbet, a friend and fellow student at the college, offered to make up the deficit.

Johnson made friends at Pembroke and read much. His tutor asked him to produce a Latin translation of Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

's ''Messiah'' as a Christmas exercise. Johnson completed half of the translation in one afternoon and the rest the following morning. Although the poem brought him praise, it did not bring the material benefit he had hoped for. The poem later appeared in ''Miscellany of Poems'' (1731), edited by John Husbands, a Pembroke tutor, and is the earliest surviving publication of any of Johnson's writings. Johnson spent the rest of his time studying, even during the Christmas holiday. He drafted a "plan of study" called "Adversaria", which he left unfinished, and used his time to learn French while working on his Greek.

Johnson's tutor, Jorden, left Pembroke some months after Johnson's arrival, and was replaced by William Adams. Johnson enjoyed Adams's tutoring, but by December, was already a quarter behind in his student fees, and was forced to return to Lichfield without a degree, having spent 13 months at Oxford. He left behind many books that he had borrowed from his father because he could not afford to transport them, and also because he hoped to return.

He eventually did receive a degree. Just before the publication of his ''Dictionary'' in 1755, the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

awarded Johnson the degree of Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Th ...

. He was awarded an honorary doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''li ...

in 1765 by Trinity College Dublin

, name_Latin = Collegium Sanctae et Individuae Trinitatis Reginae Elizabethae juxta Dublin

, motto = ''Perpetuis futuris temporibus duraturam'' (Latin)

, motto_lang = la

, motto_English = It will last i ...

and in 1775 by the University of Oxford. In 1776 he returned to Pembroke with Boswell and toured the college with his former tutor Adams, who by then was the Master of the college. During that visit he recalled his time at the college and his early career, and expressed his later fondness for Jorden.

Early career

Little is known about Johnson's life between the end of 1729 and 1731. It is likely that he lived with his parents. He experienced bouts of mental anguish and physical pain during years of illness; his tics and gesticulations associated with Tourette syndrome became more noticeable and were often commented upon. By 1731 Johnson's father was deeply in debt and had lost much of his standing in Lichfield. Johnson hoped to get an usher's position, which became available at Stourbridge Grammar School, but since he did not have a degree, his application was passed over on 6 September 1731. At about this time, Johnson's father became ill and developed an "inflammatory fever" which led to his death in December 1731 when Johnson was twenty-two. Devastated by his father's death, Johnson sought to atone for an occasion he did not go with his father to sell books. Johnson stood for a "considerable time bareheaded in the rain" in the spot his father's stall used to be. After the publication of Boswell's ''Life of Samuel Johnson,'' a statue was erected in that spot. Johnson eventually found employment as undermaster at a school inMarket Bosworth

Market Bosworth is a market town and civil parish in western Leicestershire, England. At the 2001 Census, it had a population of 1,906, increasing to 2,097 at the 2011 census. It is most famously near to the site of the decisive final battle o ...

, run by Sir Wolstan Dixie

Sir Wolstan Dixie (1524/1525 – 1594) was an English merchant and administrator, and Lord Mayor of London in 1585.

Life

He was the son of Thomas Dixie and Anne Jephson, who lived at Catworth in Huntingdonshire. Wolstan was the fourth son ...

, who allowed Johnson to teach without a degree. Johnson was treated as a servant, and considered teaching boring, but nonetheless found pleasure in it. After an argument with Dixie he left the school, and by June 1732 he had returned home.

Johnson continued to look for a position at a Lichfield school. After being turned down for a job at Ashbourne School, he spent time with his friend Edmund Hector, who was living in the home of the publisher

Johnson continued to look for a position at a Lichfield school. After being turned down for a job at Ashbourne School, he spent time with his friend Edmund Hector, who was living in the home of the publisher Thomas Warren

Thomas Warren (fl. 1727–1767) was an English bookseller, printer, publisher and businessman.

Warren was an influential figure in Birmingham at a time when it was a hotbed of creative activity, opening a bookshop in High Street, Birmingham arou ...

. At the time, Warren was starting his '' Birmingham Journal'', and he enlisted Johnson's help. This connection with Warren grew, and Johnson proposed a translation of Jerónimo Lobo

Jerónimo Lobo (1595 – 29 January 1678) was a Portuguese Jesuit missionary. He took part in the unsuccessful efforts to convert Ethiopia from the native Ethiopian church to Roman Catholicism until the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1643. Aft ...

's account of the Abyssinians. Johnson read Abbé Joachim Le Grand's French translations, and thought that a shorter version might be "useful and profitable". Instead of writing the work himself, he dictated to Hector, who then took the copy to the printer and made any corrections. Johnson's ''A Voyage to Abyssinia'' was published a year later. He returned to Lichfield in February 1734, and began an annotated edition of Poliziano

Agnolo (Angelo) Ambrogini (14 July 1454 – 24 September 1494), commonly known by his nickname Poliziano (; anglicized as Politian; Latin: '' Politianus''), was an Italian classical scholar and poet of the Florentine Renaissance. His scho ...

's Latin poems, along with a history of Latin poetry from Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited ...

to Poliziano; a ''Proposal'' was soon printed, but a lack of funds halted the project.

Johnson remained with his close friend Harry Porter during a terminal illness, which ended in Porter's death on 3 September 1734. Porter's wife Elizabeth (née Jervis) (otherwise known as "Tetty") was now a widow at the age of 45, with three children. Some months later, Johnson began to court her. William Shaw, a friend and biographer of Johnson, claims that "the first advances probably proceeded from her, as her attachment to Johnson was in opposition to the advice and desire of all her relations," Johnson was inexperienced in such relationships, but the well-to-do widow encouraged him and promised to provide for him with her substantial savings. They married on 9 July 1735, at St Werburgh's Church in Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby g ...

. The Porter family did not approve of the match, partly because of the difference in their ages: Johnson was 25 and Elizabeth was 46. Elizabeth's marriage to Johnson so disgusted her son Jervis that he severed all relations with her. However, her daughter Lucy accepted Johnson from the start, and her other son, Joseph, later came to accept the marriage.

In June 1735, while working as a tutor for the children of Thomas Whitby, a local Staffordshire gentleman, Johnson had applied for the position of headmaster at

In June 1735, while working as a tutor for the children of Thomas Whitby, a local Staffordshire gentleman, Johnson had applied for the position of headmaster at Solihull School

Solihull School is a coeducational Independent school (UK), independent day school in Solihull, West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England. Founded in 1560, it is the oldest school in the town and is a member of the Headmasters' and Headmi ...

. Although Johnson's friend Gilbert Walmisley

Gilbert Walmisley or Walmsley (1680–1751) was an English barrister, known as a friend of Samuel Johnson.

Life

Walmisley was descended from an ancient family in Lancashire. He was born in 1680, and was the son of William Walmisley of the city of ...

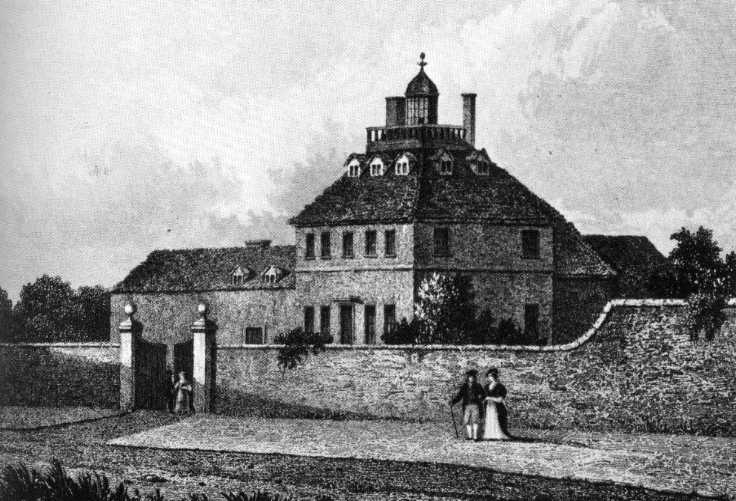

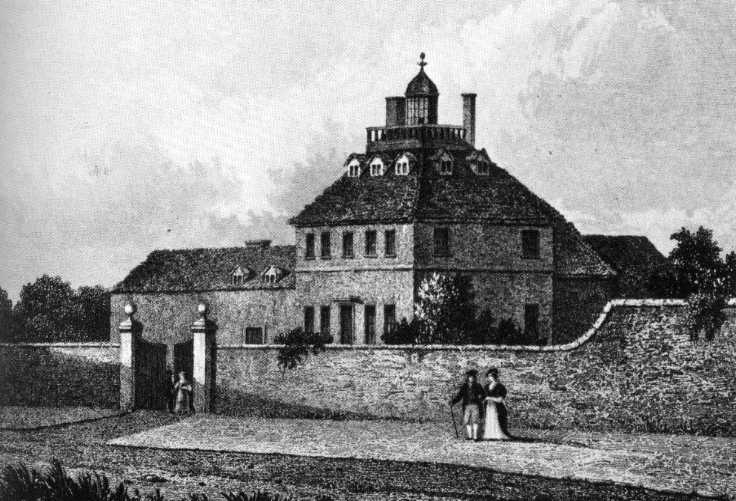

gave his support, Johnson was passed over because the school's directors thought he was "a very haughty, ill-natured gent, and that he has such a way of distorting his face (which though he can't help) the gents think it may affect some lads". With Walmisley's encouragement, Johnson decided that he could be a successful teacher if he ran his own school. In the autumn of 1735, Johnson opened Edial Hall School as a private academy at Edial

Edial is a hamlet to the east of Burntwood in Staffordshire, England. For population details taken at the 2011 census see Burntwood.

Edial Hall School, Edial, is celebrated as the house in which lexicographer, Samuel Johnson, opened an academy ...

, near Lichfield. He had only three pupils: Lawrence Offley, George Garrick, and the 18-year-old David Garrick, who later became one of the most famous actors of his day. The venture was unsuccessful and cost Tetty a substantial portion of her fortune. Instead of trying to keep the failing school going, Johnson began to write his first major work, the historical tragedy ''Irene

Irene is a name derived from εἰρήνη (eirēnē), the Greek for "peace".

Irene, and related names, may refer to:

* Irene (given name)

Places

* Irene, Gauteng, South Africa

* Irene, South Dakota, United States

* Irene, Texas, United Stat ...

''. Biographer Robert DeMaria believed that Tourette syndrome likely made public occupations like schoolmaster or tutor almost impossible for Johnson. This may have led Johnson to "the invisible occupation of authorship".

Johnson left for London with his former pupil David Garrick on 2 March 1737, the day Johnson's brother died. He was penniless and pessimistic about their travel, but fortunately for them, Garrick had connections in London, and the two were able to stay with his distant relative, Richard Norris. Johnson soon moved to Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

near the Golden Hart Tavern to finish ''Irene''. On 12 July 1737 he wrote to Edward Cave

Edward Cave (27 February 1691 – 10 January 1754) was an English printer, editor and publisher. He coined the term "magazine" for a periodical, founding ''The Gentleman's Magazine'' in 1731, and was the first publisher to successfully fashio ...

with a proposal for a translation of Paolo Sarpi's ''The History of the Council of Trent'' (1619), which Cave did not accept until months later. In October 1737 Johnson brought his wife to London, and he found employment with Cave as a writer for ''The Gentleman's Magazine

''The Gentleman's Magazine'' was a monthly magazine founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term '' magazine'' (from the French ''magazine ...

''. His assignments for the magazine and other publishers during this time were "almost unparalleled in range and variety," and "so numerous, so varied and scattered" that "Johnson himself could not make a complete list".

In May 1738 his first major work, the poem ''

In May 1738 his first major work, the poem ''London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

'', was published anonymously. Based on Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ), was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the '' Satires''. The details of Juvenal's life ...

's Satire III

The ''Satires'' () are a collection of satirical poems by the Latin author Juvenal written between the end of the first and the early second centuries A.D.

Juvenal is credited with sixteen known poems divided among five books; all are in th ...

, it describes the character Thales leaving for Wales to escape the problems of London, which is portrayed as a place of crime, corruption, and poverty. Johnson could not bring himself to regard the poem as earning him any merit as a poet. Alexander Pope said that the author "will soon be déterré" (unearthed, dug up), but this would not happen until 15 years later.

In August, Johnson's lack of an MA degree

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

from Oxford or Cambridge led to his being denied a position as master of the Appleby Grammar School. In an effort to end such rejections, Pope asked Lord Gower to use his influence to have a degree awarded to Johnson. Gower petitioned Oxford for an honorary degree to be awarded to Johnson, but was told that it was "too much to be asked". Gower then asked a friend of Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet, and Anglican cleric who became Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dubl ...

to plead with Swift to use his influence at the University of Dublin to have a master's degree awarded to Johnson, in the hope that this could then be used to justify an MA from Oxford, but Swift refused to act on Johnson's behalf.

Between 1737 and 1739, Johnson befriended poet Richard Savage. Feeling guilty of living almost entirely on Tetty's money, Johnson stopped living with her and spent his time with Savage. They were poor and would stay in taverns or sleep in "night-cellars". Some nights they would roam the streets until dawn because they had no money. During this period, Johnson and Savage worked as Grub Street

Until the early 19th century, Grub Street was a street close to London's impoverished Moorfields district that ran from Fore Street east of St Giles-without-Cripplegate north to Chiswell Street. It was pierced along its length with narrow ent ...

writers who anonymously supplied publishers with on-demand material. In his ''Dictionary,'' Johnson defined "grub street" as "the name of a street in Moorfields in London, much inhabited by writers of small histories, dictionaries, and temporary poems, whence any mean production is called ''grubstreet."'' Savage's friends tried to help him by attempting to persuade him to move to Wales, but Savage ended up in Bristol and again fell into debt. He was committed to debtors' prison and died in 1743. A year later, Johnson wrote ''Life of Mr Richard Savage

Samuel Johnson's ''Life of Mr Richard Savage'' (1744), short title ''Life of Savage'' and full title ''An Account of the Life of Mr Richard Savage, Son of the Earl Rivers'', was the first major biography published by Johnson. It was released an ...

'' (1744), a "moving" work which, in the words of the biographer and critic Walter Jackson Bate

Walter Jackson Bate (May 23, 1918 – July 26, 1999) was an American literary critic and biographer. He is known for Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography-winning biographies of Samuel Johnson (1978) and John Keats (1964).

, "remains one of the innovative works in the history of biography".

''A Dictionary of the English Language''

In 1746, a group of publishers approached Johnson with the idea of creating an authoritative dictionary of the English language. A contract with William Strahan and associates, worth 1,500guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from the Guinea region in West Africa, from where m ...

, was signed on the morning of 18 June 1746. Johnson claimed that he could finish the project in three years. In comparison, the Académie Française had 40 scholars spending 40 years to complete their dictionary, which prompted Johnson to claim, "This is the proportion. Let me see; forty times forty is sixteen hundred. As three to sixteen hundred, so is the proportion of an Englishman to a Frenchman." Although he did not succeed in completing the work in three years, he did manage to finish it in eight. Some criticised the dictionary, including the historian Thomas Babington Macaulay

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, (; 25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was a British historian and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster-General between 1846 and 1 ...

, who described Johnson as "a wretched etymologist," but according to Bate, the ''Dictionary'' "easily ranks as one of the greatest single achievements of scholarship, and probably the greatest ever performed by one individual who laboured under anything like the disadvantages in a comparable length of time."

Johnson's constant work on the ''Dictionary'' disrupted his and Tetty's living conditions. He had to employ a number of assistants for the copying and mechanical work, which filled the house with incessant noise and clutter. He was always busy, and kept hundreds of books around him. John Hawkins

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

described the scene: "The books he used for this purpose were what he had in his own collection, a copious but a miserably ragged one, and all such as he could borrow; which latter, if ever they came back to those that lent them, were so defaced as to be scarce worth owning." Johnson's process included underlining words in the numerous books he wanted to include in his ''Dictionary''. The assistants would copy out the underlined sentences on individual paper slips, which would later be alphabetized and accompanied with examples. Johnson was also distracted by Tetty's poor health as she began to show signs of a terminal illness. To accommodate both his wife and his work, he moved to 17 Gough Square near his printer, William Strahan.

In preparation, Johnson had written a ''Plan'' for the ''Dictionary''.

In preparation, Johnson had written a ''Plan'' for the ''Dictionary''. Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield

Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, (22 September 169424 March 1773) was a British statesman, diplomat, and man of letters, and an acclaimed wit of his time.

Early life

He was born in London to Philip Stanhope, 3rd Earl of Ches ...

, was the patron of the ''Plan'', to Johnson's displeasure. Seven years after first meeting Johnson to go over the work, Chesterfield wrote two anonymous essays in ''The World'' recommending the ''Dictionary''. He complained that the English language lacked structure and argued in support of the dictionary. Johnson did not like the tone of the essays, and he felt that Chesterfield had not fulfilled his obligations as the work's patron. In a letter to Chesterfield, Johnson expressed this view and harshly criticised Chesterfield, saying "Is not a patron, my lord, one who looks with unconcern on a man struggling for life in the water, and when he has reached ground, encumbers him with help? The notice which you have been pleased to take of my labours, had it been early, had been kind: but it has been delayed till I am indifferent and cannot enjoy it; till I am solitary and cannot impart it; till I am known and do not want it." Chesterfield, impressed by the language, kept the letter displayed on a table for anyone to read.

The ''Dictionary'' was finally published in April 1755, with the title page noting that the University of Oxford had awarded Johnson a Master of Arts degree in anticipation of the work. The dictionary as published was a large book. Its pages were nearly tall, and the book was wide when opened; it contained 42,773 entries, to which only a few more were added in subsequent editions, and it sold for the extravagant price of £4 10s, perhaps the rough equivalent of £350 today. An important innovation in English lexicography

Lexicography is the study of lexicons, and is divided into two separate academic disciplines. It is the art of compiling dictionaries.

* Practical lexicography is the art or craft of compiling, writing and editing dictionaries.

* Theoreti ...

was to illustrate the meanings of his words by literary quotation, of which there were approximately 114,000. The authors most frequently cited include William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, John Milton and John Dryden

''

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the per ...

. It was years before ''Johnson's Dictionary'', as it came to be known, turned a profit. Authors' royalties were unknown at the time, and Johnson, once his contract to deliver the book was fulfilled, received no further money from its sale. Years later, many of its quotations would be repeated by various editions of the ''Webster's Dictionary

''Webster's Dictionary'' is any of the English language dictionaries edited in the early 19th century by American lexicographer Noah Webster (1758–1843), as well as numerous related or unrelated dictionaries that have adopted the Webster's ...

'' and the ''New English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

''.

Johnson's dictionary was not the first, nor was it unique. Other dictionaries, such as Nathan Bailey

Nathan Bailey (died 27 June 1742), was an English philologist and lexicographer. He was the author of several dictionaries, including his '' Universal Etymological Dictionary'', which appeared in some 30 editions between 1721 and 1802. Bailey's ...

's ''Dictionarium Britannicum'', included more words, and in the 150 years preceding Johnson's dictionary about twenty other general-purpose monolingual "English" dictionaries had been produced. However, there was open dissatisfaction with the dictionaries of the period. In 1741, David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment phil ...

claimed: "The Elegance and Propriety of Stile have been very much neglected among us. We have no Dictionary of our Language, and scarce a tolerable Grammar." Johnson's ''Dictionary'' offers insights into the 18th century and "a faithful record of the language people used". It is more than a reference book; it is a work of literature. It was the most commonly used and imitated for the 150 years between its first publication and the completion of the ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a co ...

'' in 1928.

Johnson also wrote numerous essays, sermons, and poems during his years working on the dictionary. In 1750, he decided to produce a series of essays under the title ''The Rambler

''The Rambler'' was a periodical (strictly, a series of short papers) by Samuel Johnson.

Description

''The Rambler'' was published on Tuesdays and Saturdays from 1750 to 1752 and totals 208 articles. It was Johnson's most consistent and sustain ...

'' that were to be published every Tuesday and Saturday and sell for twopence

The British twopence (2''d'') ( or ) coin was a denomination of sterling coinage worth two pennies or of a pound. It was a short-lived denomination in copper, being minted in only 1797 by Matthew Boulton's Soho Mint.

These coins were made ...

each. During this time, Johnson published no fewer than 208 essays, each around 1,200-1,500 words long. Explaining the title years later, he told his friend, the painter Joshua Reynolds: "I was at a loss how to name it. I sat down at night upon my bedside, and resolved that I would not go to sleep till I had fixed its title. ''The Rambler'' seemed the best that occurred, and I took it." These essays, often on moral and religious topics, tended to be more grave than the title of the series would suggest; his first comments in ''The Rambler'' were to ask "that in this undertaking thy Holy Spirit may not be withheld from me, but that I may promote thy glory, and the salvation of myself and others." The popularity of ''The Rambler'' took off once the issues were collected in a volume; they were reprinted nine times during Johnson's life. Writer and printer Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson (baptised 19 August 1689 – 4 July 1761) was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: ''Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' (1740), '' Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady'' (1748) and ''The History of ...

, enjoying the essays greatly, questioned the publisher as to who wrote the works; only he and a few of Johnson's friends were told of Johnson's authorship. One friend, the novelist Charlotte Lennox, includes a defence of ''The Rambler'' in her novel ''The Female Quixote'' (1752). In particular, the character Mr. Glanville says, "you may sit in Judgment upon the Productions of a ''Young'', a ''Richardson'', or a ''Johnson''. Rail with premeditated Malice at the ''Rambler''; and for the want of Faults, turn even its inimitable Beauties into Ridicule." (Book VI, Chapter XI) Later, the novel describes Johnson as "the greatest Genius in the present Age."

Not all of his work was confined to ''The Rambler''. His most highly regarded poem, ''The Vanity of Human Wishes

''The Vanity of Human Wishes: The Tenth Satire of Juvenal Imitated'' is a poem by the English author Samuel Johnson. It was written in late 1748 and published in 1749 (see 1749 in poetry). It was begun and completed while Johnson was busy writ ...

'', was written with such "extraordinary speed" that Boswell claimed Johnson "might have been perpetually a poet". The poem is an imitation of Juvenal's ''Satire X

The ''Satires'' () are a collection of satirical poems by the Latin author Juvenal written between the end of the first and the early second centuries A.D.

Juvenal is credited with sixteen known poems divided among five books; all are in th ...

'' and claims that "the antidote to vain human wishes is non-vain spiritual wishes". In particular, Johnson emphasises "the helpless vulnerability of the individual before the social context" and the "inevitable self-deception by which human beings are led astray". The poem was critically celebrated but it failed to become popular, and sold fewer copies than ''London''. In 1749, Garrick made good on his promise that he would produce ''Irene'', but its title was altered to '' Mahomet and Irene'' to make it "fit for the stage." ''Irene,'' which was written in blank verse, was received rather poorly with a friend of Boswell's commenting the play to be "as frigid as the regions of Nova Zembla: now and then you felt a little heat like what is produced by touching ice." The show eventually ran for nine nights.

Tetty Johnson was ill during most of her time in London, and in 1752 she decided to return to the countryside while Johnson was busy working on his ''Dictionary''. She died on 17 March 1752, and, at word of her death, Johnson wrote a letter to his old friend Taylor, which according to Taylor "expressed grief in the strongest manner he had ever read". Johnson wrote a sermon in her honour, to be read at her funeral, but Taylor refused to read it, for reasons which are unknown. This only exacerbated Johnson's feelings of loss and despair. Consequently, John Hawkesworth had to organise the funeral. Johnson felt guilty about the poverty in which he believed he had forced Tetty to live, and blamed himself for neglecting her. He became outwardly discontented, and his diary was filled with prayers and laments over her death which continued until his own. She was his primary motivation, and her death hindered his ability to complete his work.

Later career

On 16 March 1756, Johnson was arrested for an outstanding debt of £5 18 s. Unable to contact anyone else, he wrote to the writer and publisher Samuel Richardson. Richardson, who had previously lent Johnson money, sent him six

On 16 March 1756, Johnson was arrested for an outstanding debt of £5 18 s. Unable to contact anyone else, he wrote to the writer and publisher Samuel Richardson. Richardson, who had previously lent Johnson money, sent him six guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from the Guinea region in West Africa, from where m ...

to show his good will, and the two became friends. Soon after, Johnson met and befriended the painter Joshua Reynolds, who so impressed Johnson that he declared him "almost the only man whom I call a friend". Reynolds's younger sister Frances observed during their time together "that men, women and children gathered around him ohnson, laughing at his gestures and gesticulations. In addition to Reynolds, Johnson was close to Bennet Langton and Arthur Murphy. Langton was a scholar and an admirer of Johnson who persuaded his way into a meeting with Johnson which led to a long friendship. Johnson met Murphy during the summer of 1754 after Murphy came to Johnson about the accidental republishing of the ''Rambler'' No. 190, and the two became friends. Around this time, Anna Williams Anna Williams may refer to:

* Anna Williams (poet) (1706–1783), writer and friend of Samuel Johnson

* Anna Maria Williams (1839–1929), New Zealand teacher and school principal

* Anna Wessels Williams (1863–1954), pioneering female doctor an ...

began boarding with Johnson. She was a minor poet who was poor and becoming blind, two conditions that Johnson attempted to change by providing room for her and paying for a failed cataract surgery. Williams, in turn, became Johnson's housekeeper.

To occupy himself, Johnson began to work on ''The Literary Magazine, or Universal Review'', the first issue of which was printed on 19 March 1756. Philosophical disagreements erupted over the purpose of the publication when the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

began and Johnson started to write polemical essays attacking the war. After the war began, the ''Magazine'' included many reviews, at least 34 of which were written by Johnson. When not working on the ''Magazine'', Johnson wrote a series of prefaces for other writers, such as Giuseppe Baretti

Giuseppe Marc'Antonio Baretti (24 April 1719, Turin, Piedmont – 5 May 1789, London) was an Italian Literary criticism, literary critic, poet, writer, translator, linguist and author of two influential language-translation dictionaries. During h ...

, William Payne and Charlotte Lennox. Johnson's relationship with Lennox and her works was particularly close during these years, and she in turn relied so heavily upon Johnson that he was "the most important single fact in Mrs Lennox's literary life". He later attempted to produce a new edition of her works, but even with his support they were unable to find enough interest to follow through with its publication. To help with domestic duties while Johnson was busy with his various projects, Richard Bathurst, a physician and a member of Johnson's Club, pressured him to take on a freed slave, Francis Barber

Francis Barber ( – 13 January 1801), born Quashey, was the Jamaican manservant of Samuel Johnson in London from 1752 until Johnson's death in 1784. Johnson made him his residual heir, with £70 () a year to be given him by Trustees, express ...

, as his servant.

Johnson's work on ''The Plays of William Shakespeare

''The Plays of William Shakespeare'' was an 18th-century edition of the dramatic works of William Shakespeare, edited by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens. Johnson announced his intention to edit Shakespeare's plays in his ''Miscellaneous O ...

'' took up most of his time. On 8 June 1756, Johnson published his '' Proposals for Printing, by Subscription, the Dramatick Works of William Shakespeare'', which argued that previous editions of Shakespeare were edited incorrectly and needed to be corrected. Johnson's progress on the work slowed as the months passed, and he told music historian Charles Burney in December 1757 that it would take him until the following March to complete it. Before that could happen, he was arrested again, for a debt of £40, in February 1758. The debt was soon repaid by Jacob Tonson

Jacob Tonson, sometimes referred to as Jacob Tonson the Elder (1655–1736), was an eighteenth-century English bookseller and publisher.

Tonson published editions of John Dryden and John Milton, and is best known for having obtained a copyright ...

, who had contracted Johnson to publish ''Shakespeare'', and this encouraged Johnson to finish his edition to repay the favour. Although it took him another seven years to finish, Johnson completed a few volumes of his ''Shakespeare'' to prove his commitment to the project.

In 1758, Johnson began to write a weekly series, '' The Idler'', which ran from 15 April 1758 to 5 April 1760, as a way to avoid finishing his ''Shakespeare''. This series was shorter and lacked many features of ''The Rambler''. Unlike his independent publication of ''The Rambler'', ''The Idler'' was published in a weekly news journal ''The Universal Chronicle'', a publication supported by John Payne, John Newbery

John Newbery (9 July 1713 – 22 December 1767), considered "The Father of Children's Literature", was an English publisher of books who first made children's literature a sustainable and profitable part of the literary market. He also supported ...

, Robert Stevens and William Faden.

Since ''The Idler'' did not occupy all Johnson's time, he was able to publish his philosophical novella '' Rasselas'' on 19 April 1759. The "little story book", as Johnson described it, describes the life of Prince Rasselas and Nekayah, his sister, who are kept in a place called the Happy Valley in the land of Abyssinia. The Valley is a place free of problems, where any desire is quickly satisfied. The constant pleasure does not, however, lead to satisfaction; and, with the help of a philosopher named Imlac, Rasselas escapes and explores the world to witness how all aspects of society and life in the outside world are filled with suffering. They return to Abyssinia, but do not wish to return to the state of constantly fulfilled pleasures found in the Happy Valley. ''Rasselas'' was written in one week to pay for his mother's funeral and settle her debts; it became so popular that there was a new English edition of the work almost every year. References to it appear in many later works of fiction, including ''Jane Eyre

''Jane Eyre'' ( ; originally published as ''Jane Eyre: An Autobiography'') is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name "Currer Bell" on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The first ...

'', '' Cranford'' and ''The House of the Seven Gables

''The House of the Seven Gables: A Romance'' is a Gothic novel written beginning in mid-1850 by American author Nathaniel Hawthorne and published in April 1851 by Ticknor and Fields of Boston. The novel follows a New England family and their anc ...

''. Its fame was not limited to English-speaking nations: ''Rasselas'' was immediately translated into five languages (French, Dutch, German, Russian and Italian), and later into nine others.

By 1762, however, Johnson had gained notoriety for his dilatoriness in writing; the contemporary poet Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

teased Johnson for the delay in producing his long-promised edition of Shakespeare: "He for subscribers baits his hook / and takes your cash, but where's the book?" The comments soon motivated Johnson to finish his ''Shakespeare'', and, after receiving the first payment from a government pension on 20 July 1762, he was able to dedicate most of his time towards this goal. Earlier that July, the 24-year-old King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

granted Johnson an annual pension of £300 in appreciation for the ''Dictionary''. While the pension did not make Johnson wealthy, it did allow him a modest yet comfortable independence for the remaining 22 years of his life. The award came largely through the efforts of Sheridan and the Earl of Bute

Marquess of the County of Bute, shortened in general usage to Marquess of Bute, is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1796 for John Stuart, 4th Earl of Bute.

Family history

John Stuart was the member of a family that ...

. When Johnson questioned if the pension would force him to promote a political agenda or support various officials, he was told by Bute that the pension "is not given you for anything you are to do, but for what you have done".

On 16 May 1763, Johnson first met 22-year-old James Boswell

James Boswell, 9th Laird of Auchinleck (; 29 October 1740 ( N.S.) – 19 May 1795), was a Scottish biographer, diarist, and lawyer, born in Edinburgh. He is best known for his biography of his friend and older contemporary the English writer ...

—who would later become Johnson's first major biographer—in the bookshop of Johnson's friend, Tom Davies. They quickly became friends, although Boswell would return to his home in Scotland or travel abroad for months at a time. Around the spring of 1763, Johnson formed " The Club", a social group that included his friends Reynolds, Burke

Burke is an Anglo-Norman Irish surname, deriving from the ancient Anglo-Norman and Hiberno-Norman noble dynasty, the House of Burgh. In Ireland, the descendants of William de Burgh (–1206) had the surname ''de Burgh'' which was gaelicised ...

, Garrick, Goldsmith

A goldsmith is a metalworker who specializes in working with gold and other precious metals. Nowadays they mainly specialize in jewelry-making but historically, goldsmiths have also made silverware, platters, goblets, decorative and servicea ...

and others (the membership later expanded to include Adam Smith and Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and member of parliament. His most important work, '' The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, is ...

, in addition to Boswell himself). They decided to meet every Monday at 7:00 pm at the Turk's Head in Gerrard Street, Soho

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster, part of the West End of London. Originally a fashionable district for the aristocracy, it has been one of the main entertainment districts in the capital since the 19th century.

The area was develo ...

, and these meetings continued until long after the deaths of the original members.

On 9 January 1765, Murphy introduced Johnson to Henry Thrale

Henry Thrale (1724/1730?–4 April 1781) was a British politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1765 to 1780. He was a close friend of Samuel Johnson. Like his father, he was the proprietor of the large London brewery H. Thrale & Co.

B ...

, a wealthy brewer and MP, and his wife Hester. They struck up an instant friendship; Johnson was treated as a member of the family, and was once more motivated to continue working on his ''Shakespeare''. Afterwards, Johnson stayed with the Thrales for 17 years until Henry's death in 1781, sometimes staying in rooms at Thrale's Anchor Brewery in Southwark. Hester Thrale's documentation of Johnson's life during this time, in her correspondence and her diary (''Thraliana

The ''Thraliana'' was a diary kept by Hester Thrale and is part of the genre known as table talk. Although the work began as Thrale's diary focused on her experience with her family, it slowly changed focus to emphasise various anecdotes and sto ...

''), became an important source of biographical information on Johnson after his death.

Johnson's edition of ''Shakespeare'' was finally published on 10 October 1765 as ''The Plays of William Shakespeare, in Eight Volumes ... To which are added Notes by Sam. Johnson'' in a printing of one thousand copies. The first edition quickly sold out, and a second was soon printed. The plays themselves were in a version that Johnson felt was closest to the original, based on his analysis of the manuscript editions. Johnson's revolutionary innovation was to create a set of corresponding notes that allowed readers to clarify the meaning behind many of Shakespeare's more complicated passages, and to examine those which had been transcribed incorrectly in previous editions. Included within the notes are occasional attacks upon rival editors of Shakespeare's works. Years later, Edmond Malone

Edmond Malone (4 October 174125 May 1812) was an Irish Shakespearean scholar and editor of the works of William Shakespeare.

Assured of an income after the death of his father in 1774, Malone was able to give up his law practice for at first p ...

, an important Shakespearean scholar and friend of Johnson's, stated that Johnson's "vigorous and comprehensive understanding threw more light on his authour than all his predecessors had done".

Final works

On 6 August 1773, eleven years after first meeting Boswell, Johnson set out to visit his friend in Scotland, and to begin "a journey to the western islands of Scotland", as Johnson's 1775 account of their travels would put it. That account was intended to discuss the social problems and struggles that affected the Scottish people, but it also praised many of the unique facets of Scottish society, such as a school in Edinburgh for the deaf and mute. Also, Johnson used the work to enter into the dispute over the authenticity of James Macpherson's Ossian poems, claiming they could not have been translations of ancient Scottish literature on the grounds that "in those times nothing had been written in the Earse .e. Scots Gaeliclanguage". There were heated exchanges between the two, and according to one of Johnson's letters, MacPherson threatened physical violence. Boswell's account of their journey, '' The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides'' (1786), was a preliminary step toward his later biography, '' The Life of Samuel Johnson''. Included were various quotations and descriptions of events, including anecdotes such as Johnson swinging a

On 6 August 1773, eleven years after first meeting Boswell, Johnson set out to visit his friend in Scotland, and to begin "a journey to the western islands of Scotland", as Johnson's 1775 account of their travels would put it. That account was intended to discuss the social problems and struggles that affected the Scottish people, but it also praised many of the unique facets of Scottish society, such as a school in Edinburgh for the deaf and mute. Also, Johnson used the work to enter into the dispute over the authenticity of James Macpherson's Ossian poems, claiming they could not have been translations of ancient Scottish literature on the grounds that "in those times nothing had been written in the Earse .e. Scots Gaeliclanguage". There were heated exchanges between the two, and according to one of Johnson's letters, MacPherson threatened physical violence. Boswell's account of their journey, '' The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides'' (1786), was a preliminary step toward his later biography, '' The Life of Samuel Johnson''. Included were various quotations and descriptions of events, including anecdotes such as Johnson swinging a broadsword

The basket-hilted sword is a sword type of the early modern era characterised by a basket-shaped guard that protects the hand. The basket hilt is a development of the quillons added to swords' crossguards since the Late Middle Ages.

In m ...

while wearing Scottish garb, or dancing a Highland jig.

In the 1770s, Johnson, who had tended to be an opponent of the government early in life, published a series of pamphlets in favour of various government policies. In 1770 he produced ''The False Alarm'', a political pamphlet attacking John Wilkes

John Wilkes (17 October 1725 – 26 December 1797) was an English radical journalist and politician, as well as a magistrate, essayist and soldier. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlesex election dispute, he f ...

. In 1771, his ''Thoughts on the Late Transactions Respecting Falkland's Islands'' cautioned against war with Spain. In 1774 he printed ''The Patriot'', a critique of what he viewed as false patriotism. On the evening of 7 April 1775, he made the famous statement, "Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel." This line was not, as widely believed, about patriotism in general, but what Johnson considered to be the false use of the term "patriotism" by Wilkes and his supporters. Johnson opposed "self-professed Patriots" in general, but valued what he considered "true" patriotism.

The last of these pamphlets, ''Taxation No Tyranny'' (1775), was a defence of the Coercive Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measure ...

and a response to the Declaration of Rights of the First Continental Congress, which protested against taxation without representation

"No taxation without representation" is a political slogan that originated in the American Revolution, and which expressed one of the primary grievances of the American colonists for Great Britain. In short, many colonists believed that as they ...

. Johnson argued that in emigrating to America, colonists had "voluntarily resigned the power of voting", but they still retained "virtual representation

Virtual representation was the idea that the members of Parliament, including the Lords and the Crown-in-Parliament, reserved the right to speak for the interests of all British subjects, rather than for the interests of only the district that ele ...