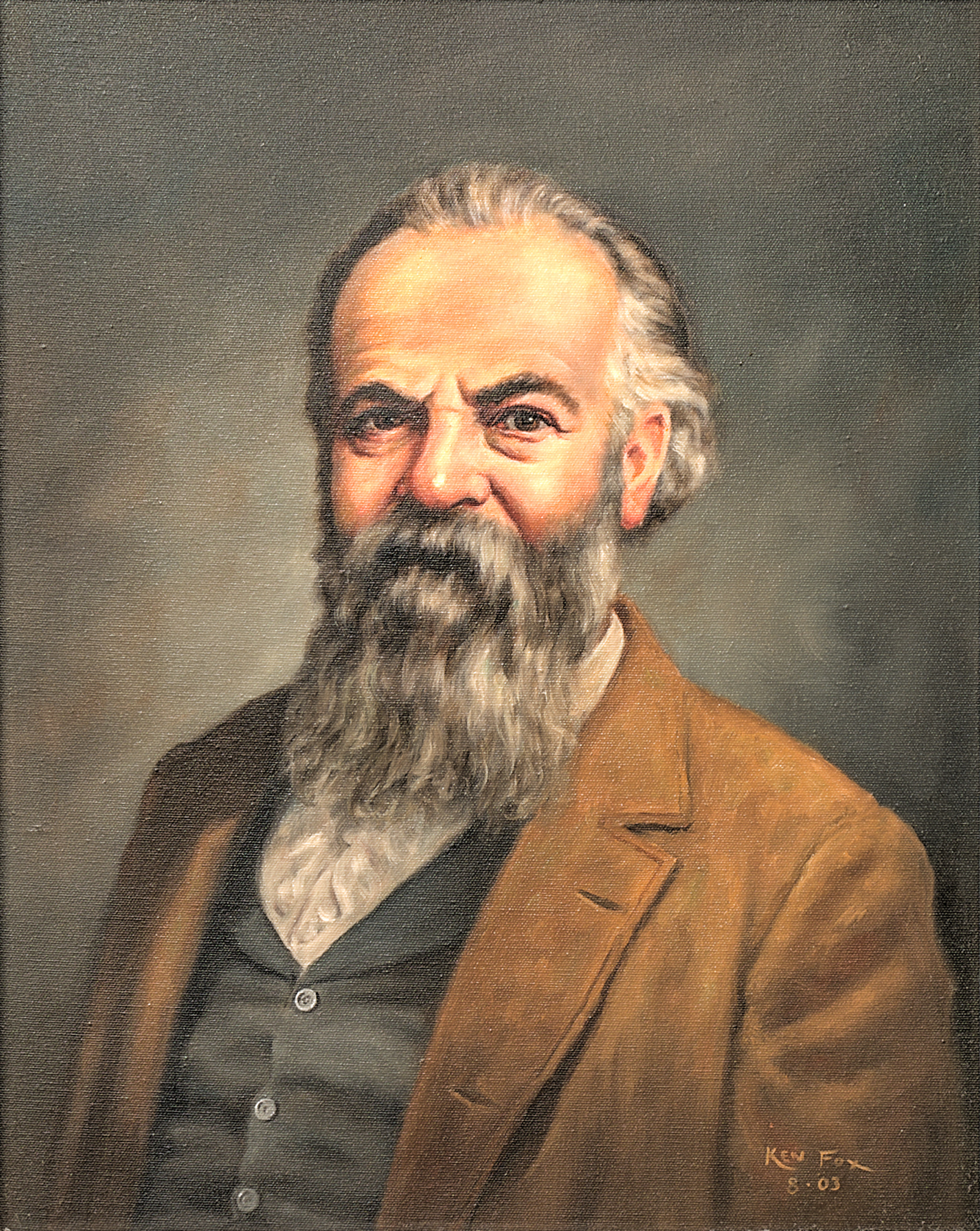

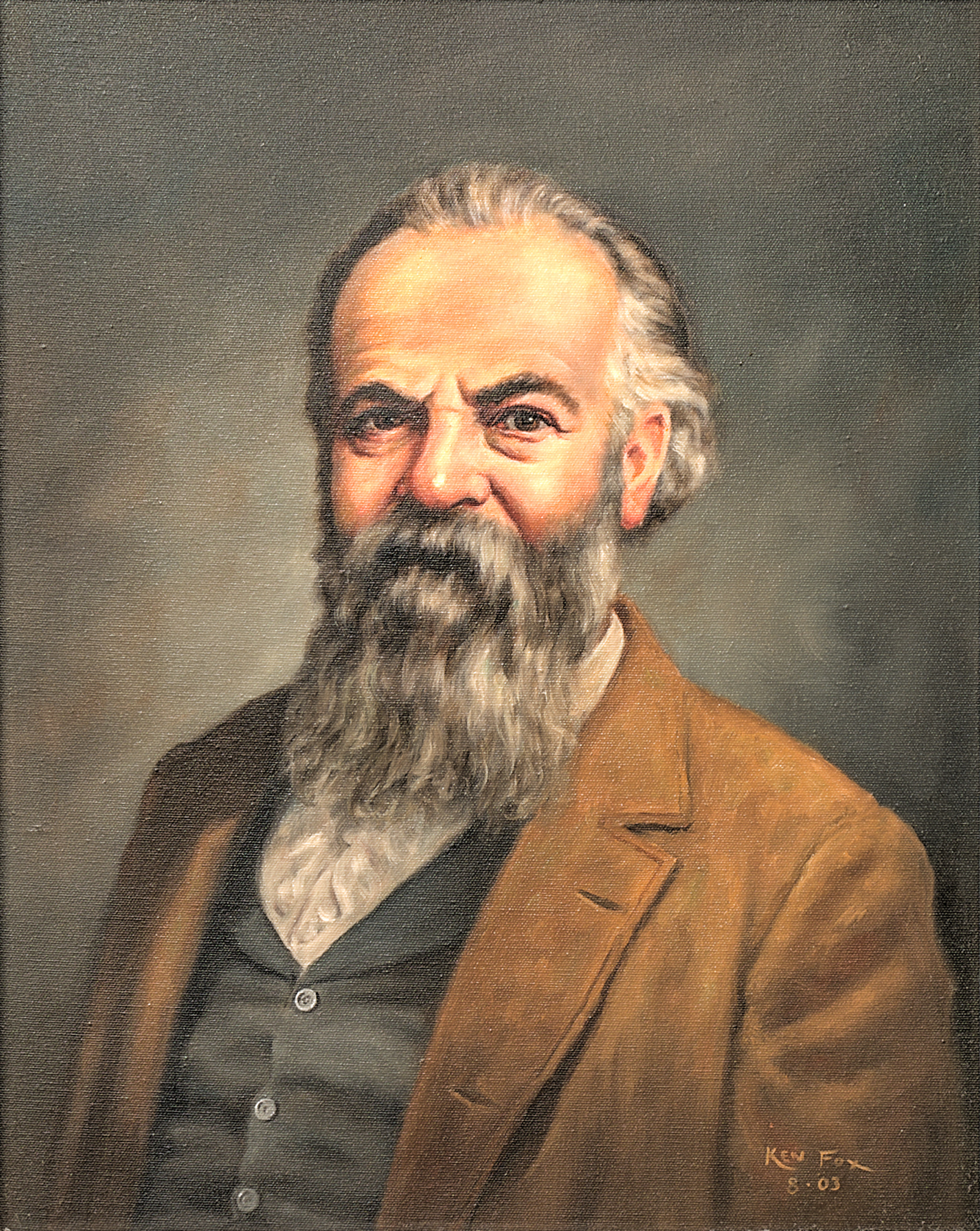

John Wesley Powell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Wesley Powell (March 24, 1834 – September 23, 1902) was an American geologist, U.S. Army soldier, explorer of the

John Wesley Powell (March 24, 1834 – September 23, 1902) was an American geologist, U.S. Army soldier, explorer of the

After 1867, Powell led a series of expeditions into the Rocky Mountains and around the

After 1867, Powell led a series of expeditions into the Rocky Mountains and around the  The expedition's route traveled through the Utah canyons of the Colorado River, which Powell described in his published diary as having

The expedition's route traveled through the Utah canyons of the Colorado River, which Powell described in his published diary as having

Powell became the director of the

Powell became the director of the

The railroad companies owned – vast tracts of lands granted in return for building the railways – and did not agree with Powell’s views on land conservation. They aggressively lobbied Congress to reject Powell’s policy proposals and to encourage farming instead, as they wanted to cash in on their lands. The U.S. Congress went along and developed legislation that encouraged pioneer settlement of the American West based on agricultural use of land. Politicians based their decisions on a theory of Professor Cyrus Thomas who was a protege of Horace Greeley. Thomas suggested that agricultural development of land would change climate and cause higher amounts of precipitations, claiming that ‘ rain follows the plow’, a theory which has since been largely discredited.

At an 1883 irrigation conference, Powell would prophetically remark: “Gentlemen, you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not sufficient water to supply the land.” Powell's recommendations for development of the West were largely ignored until after the Dust Bowl of the 1920s and 1930s, resulting in untold suffering associated with pioneer subsistence farms that failed because of insufficient rain and irrigation water.

The railroad companies owned – vast tracts of lands granted in return for building the railways – and did not agree with Powell’s views on land conservation. They aggressively lobbied Congress to reject Powell’s policy proposals and to encourage farming instead, as they wanted to cash in on their lands. The U.S. Congress went along and developed legislation that encouraged pioneer settlement of the American West based on agricultural use of land. Politicians based their decisions on a theory of Professor Cyrus Thomas who was a protege of Horace Greeley. Thomas suggested that agricultural development of land would change climate and cause higher amounts of precipitations, claiming that ‘ rain follows the plow’, a theory which has since been largely discredited.

At an 1883 irrigation conference, Powell would prophetically remark: “Gentlemen, you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not sufficient water to supply the land.” Powell's recommendations for development of the West were largely ignored until after the Dust Bowl of the 1920s and 1930s, resulting in untold suffering associated with pioneer subsistence farms that failed because of insufficient rain and irrigation water.

In recognition of his national service, Powell was buried in

In recognition of his national service, Powell was buried in

Biographical sketch (1903)

by Frederick S. Dellenbaugh

NPS John Wesley Powell Photograph Index * * *

John Wesley Powell Student Research Conference

at Illinois Wesleyan University

John Wesley Powell Collection of Pueblo Pottery

at Illinois Wesleyan University Ames Library

Powell Museum

Page, Arizona

John Wesley Powell River History Museum

"John Wesley Powell"

by James M. Aton in th

Western Writers Series Digital Editions

at Boise State University

"A Canyon Voyage, The Narrative of the Second Powell Expedition down the Green-Colorado River from Wyoming, and the Explorations on Land, in the Years 1871 and 1872"

(1908) by Frederick Samuel Dellenbaugh at Project Gutenberg. *

Powell, J. W., In Fowler, D. D., & In Fowler, C. S. (1971). Anthropology of the Numa: John Wesley Powell's manuscripts on the Numic peoples of Western North America, 1868–1880. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press; for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off..

Fowler, D. D., Matley, J. F., & National Museum of Natural History (U.S.). (1979). Material culture of the Numa: The John Wesley Powell Collection, 1867–1880. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

in the ttp://anthropology.si.edu/cm/ Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution

{{DEFAULTSORT:Powell, John Wesley 1834 births 1902 deaths American explorers Explorers of North America Explorers of the United States American geologists American conservationists Smithsonian Institution people Illinois College alumni Oberlin College alumni People of Illinois in the American Civil War Union Army officers Early Grand Canyon river runners People from Boone County, Illinois Wheaton College (Illinois) alumni Illinois Wesleyan University faculty Illinois State University faculty People from Mount Morris, New York American people of English descent Linguists from the United States United States Geological Survey personnel American civil servants American amputees National Geographic Society founders Burials at Arlington National Cemetery History of the Rocky Mountains Activists from New York (state) Linguists of Hokan languages Members of the American Antiquarian Society Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Linguists of indigenous languages of North America

John Wesley Powell (March 24, 1834 – September 23, 1902) was an American geologist, U.S. Army soldier, explorer of the

John Wesley Powell (March 24, 1834 – September 23, 1902) was an American geologist, U.S. Army soldier, explorer of the American West

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

, professor at Illinois Wesleyan University, and director of major scientific and cultural institutions. He is famous for his 1869 geographic expedition, a three-month river trip down the Green

Green is the color between cyan and yellow on the visible spectrum. It is evoked by light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 495570 Nanometre, nm. In subtractive color systems, used in painting and color printing, it is created by ...

and Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

rivers, including the first official U.S. government-sponsored passage through the Grand Canyon.

Powell was appointed by US President James A. Garfield to serve as the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey (1881–1894) and proposed, for development of the arid West, policies that were prescient for his accurate evaluation of conditions. Two years prior to his service as director of the U.S. Geological Survey, Major Powell had become the first director of the Bureau of Ethnology

The Bureau of American Ethnology (or BAE, originally, Bureau of Ethnology) was established in 1879 by an act of Congress for the purpose of transferring archives, records and materials relating to the Indians of North America from the Interior D ...

at the Smithsonian Institution where he supported linguistic and sociological research and publications.

Biography

Early life

Powell was born in Mount Morris, New York, in 1834, the son of Joseph and Mary Powell. His father, a poor itinerant preacher, had emigrated to the U.S. from Shrewsbury,England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, in 1831. His family moved westward to Jackson, Ohio, then to Walworth County, Wisconsin, before settling in rural Boone County, Illinois.

As a young man he undertook a series of adventures through the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it ...

valley. In 1855, he spent four months walking across Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

. During 1856, he rowed the Mississippi from St. Anthony Saint Anthony, Antony, or Antonius most often refers to Anthony of Padua, also known as Saint Anthony of Lisbon, the patron saint of lost things. This name may also refer to:

People

* Anthony of Antioch (266–302), Martyr under Diocletian. Feast ...

, Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the List of U.S. states and territories by population, 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minne ...

, to the sea. In 1857, he rowed down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

to the Mississippi River, traveling north to reach St. Louis. In 1858, he rowed down the Illinois River

The Illinois River ( mia, Inoka Siipiiwi) is a principal tributary of the Mississippi River and is approximately long. Located in the U.S. state of Illinois, it has a drainage basin of . The Illinois River begins at the confluence of the ...

, then up the Mississippi and the Des Moines River to central Iowa

Iowa () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wiscon ...

. In 1859, at age 25, he was elected to the Illinois Natural History Society.

Education

Powell studied at Illinois College, Illinois Institute (which would later becomeWheaton College Wheaton College may refer to:

* Wheaton College (Illinois), a private Christian, coeducational, liberal arts college in Wheaton, Illinois

* Wheaton College (Massachusetts)

Wheaton College is a private liberal arts college in Norton, Massachus ...

), and Oberlin College, over a period of seven years while teaching, but was unable to attain his degree. During his studies Powell acquired a knowledge of Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

. Powell had a restless nature and a deep interest in the natural sciences. This desire to learn about natural sciences was against the wishes of his father, yet Powell was still determined to do so. In 1861 when Powell was on a lecture tour he decided that a civil war was inevitable; he decided to study military science and engineering to prepare himself for the imminent conflict.

Civil War and aftermath

Powell's loyalties remained with the Union and the cause of abolishingslavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. On May 8, 1861, he enlisted at Hennepin, Illinois, as a private in the 20th Illinois Infantry. He was elected sergeant-major of the regiment, and when the 20th Illinois was mustered into the Federal service a month later, Powell was commissioned a second lieutenant. He enlisted in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

as a cartographer, topographer and military engineer.

While stationed at Cape Girardeau, Missouri, he recruited an artillery company that became Battery ‘F’ of the 2nd Illinois Light Artillery, with Powell as captain. On November 28, 1861, Powell took a brief leave to marry Emma Dean. At the Battle of Shiloh, he lost most of his right arm when struck by a Minié ball while in the process of giving the order to fire. The raw nerve endings in his arm caused him pain for the rest of his life.

Despite the loss of an arm, he returned to the Army and was present at the battles of Champion Hill, Big Black River Bridge, and in the siege of Vicksburg. Always the geologist, he took to studying rocks while in the trenches at Vicksburg. He was made a major and commanded an artillery brigade with the 17th Army Corps during the Atlanta campaign. After the fall of Atlanta he was transferred to George H. Thomas’ army and participated in the battle of Nashville

The Battle of Nashville was a two-day battle in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign that represented the end of large-scale fighting west of the coastal states in the American Civil War. It was fought at Nashville, Tennessee, on December 15–16, 18 ...

. At the end of the war he was made a brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

lieutenant colonel but preferred to use the title of “major”.

After leaving the Army, Powell took the post of professor of geology at Illinois Wesleyan University. He also lectured at Illinois State Normal University for most of his career. Powell helped expand the collections of the Museum of the Illinois State Natural History Society, where he served as curator. He declined a permanent appointment in favor of exploration of the American West.

Geologic research

Expeditions

After 1867, Powell led a series of expeditions into the Rocky Mountains and around the

After 1867, Powell led a series of expeditions into the Rocky Mountains and around the Green

Green is the color between cyan and yellow on the visible spectrum. It is evoked by light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 495570 Nanometre, nm. In subtractive color systems, used in painting and color printing, it is created by ...

and Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

rivers. One of these expeditions was with his students and his wife, to collect specimens all over Colorado. Powell, William Byers, and five other men were the first white men to climb Longs Peak in 1868.

In 1869, he set out to explore the Colorado River and the Grand Canyon. Gathering ten men, four boats and food for 10 months, he set out from Green River, Wyoming, on May 24. Passing through dangerous rapids, the group passed down the Green River to its confluence with the Colorado River (then also known as the Grand River upriver from the junction), near present-day Moab, Utah, and completed the journey on August 30, 1869.

The members of the first Powell expedition were:

* John Wesley Powell, trip organizer and leader, major in the Civil War

* John Colton “Jack” Sumner, hunter, trapper, soldier in the Civil War

* William H. Dunn, hunter, trapper from Colorado

* Walter H. Powell, captain in the Civil War, John's brother

* George Y. Bradley, lieutenant in the Civil War, expedition chronicler

* Oramel G. Howland, printer, editor, hunter

* Seneca Howland, soldier who was wounded in the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of th ...

* Frank Goodman, Englishman, adventurer

* W.R. Hawkins, cook, soldier in Civil War

* Andrew Hall, Scotsman, the youngest of the expedition

The expedition's route traveled through the Utah canyons of the Colorado River, which Powell described in his published diary as having

The expedition's route traveled through the Utah canyons of the Colorado River, which Powell described in his published diary as having

... wonderful features—carved walls, royal arches, glens, alcove gulches, mounds and monuments. From which of these features shall we select a name? We decide to call it Glen Canyon.Frank Goodman quit after the first month, and Dunn and the Howland brothers left at Separation Canyon in the third month. This was just two days before the group reached the mouth of the Virgin River on August 30, after traversing almost . The three disappeared; some historians have speculated they were killed by the Shivwits Band of Paiutes or by Mormons in the town of Toquerville. (and other reprint editions) Powell retraced part of the 1869 route in 1871–72 with another expedition that traveled the Colorado River from Green River, Wyoming to Kanab Creek in the Grand Canyon. Powell used three photographers on this expedition; Elias Olcott Beaman, James Fennemore, and John K. Hillers. This trip resulted in photographs (by John K. Hillers), an accurate map and various papers. At least one Powell scholar,

Otis R. Marston

Otis Reed "Dock" Marston (February 11, 1894 – August 30, 1979) was an American writer, historian and Grand Canyon river runner who participated in a large number of river-running firsts. Marston was the eighty-third person to successfully comp ...

, noted the maps produced from the survey were impressionistic rather than precise. In planning this expedition, he employed the services of Jacob Hamblin, a Mormon missionary in southern Utah who had cultivated relationships with Native Americans. Before setting out, Powell used Hamblin as a negotiator to ensure the safety of his expedition from local Indian groups.

After the Colorado

In 1881, Powell was appointed the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey, a post he held until his resignation in 1894, being replaced by Charles Walcott. In 1875, Powell published a book based on his explorations of the Colorado, originally titled ''Report of the Exploration of the Columbia River of the West and Its Tributaries''. It was revised and reissued in 1895 as ''The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons

''The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons'' by John Wesley Powell is a classic of American exploration literature. It is about the Powell Geographic Expedition of 1869 which was the first trip down the Colorado River by boat, includi ...

''. In 1889, the intellectual gatherings Powell hosted in his home were formalized as the Cosmos Club. The club has continued, with members elected to the club for their contributions to scholarship and civic activism.

In the early 1900s the journals of the expedition crew began to be published starting with Dellenbaugh's ''A Canyon Voyage'' in 1908, followed in 1939 by the diary of Almon Harris Thompson

Almon Harris Thompson (September 24, 1839 – July 31, 1906), also known as A. H. Thompson, was an American topographer, geologist, explorer, educator and Civil War veteran. Often called "The Professor" or simply "Prof", Thompson is perhaps best ...

, who was married to Powell's sister, Ellen Powell Thompson

Ellen Louella (Nellie) Powell Thompson (1840–1911) was an American naturalist and botanist, and an active advocate for women's suffrage.

Life

Ellen Louella (Nellie) Powell Thompson was born in Ohio to parents of English origin. Her siblings i ...

. Bishop, Steward, W.C. Powell, and Jones’ diaries were all published in 1947. These diaries made it clear Powell's writings contained some exaggerations and recounted activities that occurred on the second river trip as if they occurred on the first. They also revealed that Powell, who had only one arm, wore a life jacket, though the other men did not have them.

Anthropological research

Powell became the director of the

Powell became the director of the Bureau of Ethnology

The Bureau of American Ethnology (or BAE, originally, Bureau of Ethnology) was established in 1879 by an act of Congress for the purpose of transferring archives, records and materials relating to the Indians of North America from the Interior D ...

at the Smithsonian Institution in 1879 and remained so until his death. Under his leadership, the Smithsonian published an influential classification of North American Indian languages. In 1898, Powell was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society.

As an ethnologist and early anthropologist, Powell was a follower of Lewis Henry Morgan. He classified human societies into ‘savagery’, ‘barbarism’, and ‘civilization’. Powell's criteria were based on consideration of adoption of technology, family and social organization, property relations, and intellectual development. In his view, all societies were to progress toward civilization. Powell is credited with coining the word “ acculturation”, first using it in an 1880 report by the U.S. Bureau of American Ethnography. In 1883, Powell defined “acculturation” as psychological changes induced by cross-cultural imitation.

Powell published extensive anthropological studies on the Ute people inhabiting the canyon lands around the Colorado River. His views towards these populations, along with his scientific approach, was built on social Darwinist thought; he focused on defining what features distinguished Native Americans as ‘barbaric’, placing them above ‘savagery’ but below ‘civilized’ white Europeans. Indeed, the study of ethnology was a way for scientists to demarcate social categories in order to justify government-sponsored programs that exploited newly appropriated land and its inhabitants. Powell advocated for government funding to be used to ‘civilize’ Native American populations, pushing for the teaching of English, Christianity, and Western methods of farming and manufacture.

In his book ''The Exploration of the Canyons of the Colorado'', Powell is motivated to conduct ethnologic studies because "these Indians are more nearly in their primate condition than any others on the continent with whom I am acquainted." As Wallace Stegner posits in ''Beyond the 100th Meridian'', by 1869, many Native American tribes had been pushed to extinction, and those that were known were considered corrupted by intercultural exchange. Even in 1939, Julian Steward, an anthropologist compiling photographs from Powell's 1873 expedition suggested that: “Fascinated at finding ative Americansnearly untouched by civilization, he developed a deep interest in ethnology ... Few explorers in the United States have had a comparable opportunity to study and photograph Indians so nearly in their aboriginal state.”

Powell created Illinois State University’s first Museum of Anthropology which at the time was called the finest in all of North America. Powell held a post as lecturer on the History of Culture in the Political Science department at the Columbian University in Washington, D.C. from 1894 to 1899. Powell's contribution to anthropology and scientific racism is not well known in the geosciences, however a recent article revisited Powell's legacy in terms of his social and political impact on Native Americans.

Environmentalism

In ''Cadillac Desert'', Powell is portrayed as a champion of land preservation and conservation. Powell’s expeditions led to his belief that the arid West was not suitable for agricultural development, except for about 2% of the lands that were near water sources. His '' Report on the Lands of the Arid Regions of the United States'' proposedirrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow crops, landscape plants, and lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,000 years and has been dev ...

systems and state boundaries based on watershed

Watershed is a hydrological term, which has been adopted in other fields in a more or less figurative sense. It may refer to:

Hydrology

* Drainage divide, the line that separates neighbouring drainage basins

* Drainage basin, called a "watershe ...

areas to avoid disagreements between states. For the remaining lands, he proposed conservation and low-density, open grazing.

Legacy, honours, and namesakes

In recognition of his national service, Powell was buried in

In recognition of his national service, Powell was buried in Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography an ...

. The John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act, signed 12 March 2019, authorizes the establishment of the "John Wesley Powell National Conservation Area", consisting of approximately 29,868 acres of land in Utah. Green River, Wyoming, the embarkation site of both Powell expeditions, commissioned a statue depicting Powell holding an oar, in front of the Sweetwater County History Museum. In Powell's honor, the USGS National Center in Reston, Virginia, was dedicated as the "John Wesley Powell Federal Building" in 1974. In addition, the highest award presented by the USGS to persons outside the federal government is named the John Wesley Powell Award The John Wesley Powell Award is a United States Geological Survey (USGS) honor award that recognizes an individual or group, not employed by the U.S. federal government, for noteworthy contributions to the objectives and mission of the USGS.

The aw ...

. In 1984, he was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

The following were named after Powell:

* The rare mineral powellite.

* Lake Powell, a man-made reservoir on the Colorado River.

* Mount Powell, a summit in the Sierra Nevada of California.

* Powell Peak

Powell Peak is a summit in Grand County, Colorado, in the United States. With an elevation of , Powell Peak is the 493rd-highest summit in the state of Colorado.

The peak was named for John Wesley Powell. The mountain's toponym was officially ad ...

.

* Powell Plateau, near Steamboat Mountain on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon.

* Powell, Wyoming, and the Powell Flats area.

* The residential building of the Criminal Justice Services Department of Mesa County in Grand Junction, Colorado.

* John Wesley Powell Middle School in Littleton, Colorado.

* Powell Junior High School in Mesa, Arizona.

Awards

An article inScientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it i ...

notes the following awards:

* 1886 – Honorary Ph.D. from University of Heidelberg on 500th anniversary

* 1886 – Honorary LL.D. from Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

on 230th anniversary

* elected to National Academy of Sciences

* president of Anthropological Society of Washington

Anthropology is the Science, scientific study of Human, humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including Homo, past human species. Social anthropolog ...

1879–1888

* 1884 – president of Philosophical Society of Washington

* 1874 – elected member and fellow of American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)

* 1875 – vice president of AAAS

Personal life

On November 28, 1861, while serving as captain of Battery ‘F’ of the 2nd Illinois Light Artillery at Cape Girardeau, Missouri, he took a brief leave to marry Emma Dean. On September 10, 1871, Emma Dean gave birth to the Powells' only child, Mary Dean Powell inSalt Lake City, Utah

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

. She was active in the Wimodaughsis, a national women's club in Washington, D.C., started by Anna Howard Shaw and Susan B. Anthony. Emma Dean Powell died on March 13, 1924, in Washington, D.C. She is buried along with her husband in Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

.

Notes

References

* Powell, J.W. (1875). ''The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons

''The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons'' by John Wesley Powell is a classic of American exploration literature. It is about the Powell Geographic Expedition of 1869 which was the first trip down the Colorado River by boat, includi ...

''. New York: Dover Press (reprint) .

* Ross, John F. (2018). ''The Promise of the Grand Canyon: John Wesley Powell's perilous journey and his vision for the American West''. Viking. .

* Aton, James M. (2010). ''John Wesley Powell: His life and legacy''.

* Boas, F.; Powell, J.W. (1991) ''Introduction to Handbook of American Indian Languages'' plus ''Indian Linguistic Families of America North of Mexico''. University of Nebraska Press, (double book volume).

* Darrah, William Culp, Ralph V. Chamberlin

Ralph Vary Chamberlin (January 3, 1879October 31, 1967) was an American biologist, ethnographer, and historian from Salt Lake City, Utah. He was a faculty member of the University of Utah for over 25 years, where he helped establish the School of ...

, and Charles Kelly. (2009). ''The Exploration of the Colorado River in 1869 and 1871–1872: Biographical Sketches and Original Documents of the First Powell Expedition of 1869 and the Second Powell Expedition of 1871–1872''. University of Utah Press. .

* Dolnick, Edward (2002). ''Down the Great Unknown: John Wesley Powell's 1869 journey of discovery and tragedy through the Grand Canyon''. Harper Perennial (paperback) .

* Dolnick, Edward (2001). ''Down the Great Unknown: John Wesley Powell's 1869 journey of discovery and tragedy through the Grand Canyon''. (hardcover) Harper Collins Publishers .

* Ghiglieri, Michael P.; Bradley, George Y. (2003). ''First Through Grand Canyon: The secret journals & letters of the 1869 crew who explored the Green and Colorado Rivers''. Puma Press (paperback) .

* Judd, Neil Merton (1967). ''The Bureau of American Ethnology: A partial history''. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

* Marston, Otis R. (2014). ''From Powell to Power: A recounting of the first one hundred river runners through the Grand Canyon'', pp. 111–114. Flagstaff, Arizona: Vishnu Temple Press .

* Heacox, Kim; Kostyal, K.M.; Walker, Paul Robert (1 September 1999). ''Exploring the Great Rivers of North America''. National Geographic Society (first ed.) , .

* Reisner, Marc (1993). ''Cadillac Desert: The American West and its disappearing water''. Penguin Books (paperback) .

* Stegner, Wallace (1954). ''Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the second opening of the West''. University of Nebraska Press (and other reprint editions) .

*

*

* Reisner, Marc (1986). "Cadillac Desert: the American West and its Disappearing Water".

* Powell, J.W. (1876). ''A Report on the Arid Regions of the United States, with a More Detailed Account of the Lands of Utah''

External links

Biographical sketch (1903)

by Frederick S. Dellenbaugh

NPS John Wesley Powell Photograph Index * * *

John Wesley Powell Student Research Conference

at Illinois Wesleyan University

John Wesley Powell Collection of Pueblo Pottery

at Illinois Wesleyan University Ames Library

Powell Museum

Page, Arizona

John Wesley Powell River History Museum

Green River, Utah

Green River is a city in Emery County, Utah. The population was 847 at the 2020 census.

History

The city of Green River is located in ancestral Ute lands, in the home locale of the Seuvarits/Sheberetch band of Ute people. The Old Spanish Trail ...

"John Wesley Powell"

by James M. Aton in th

Western Writers Series Digital Editions

at Boise State University

"A Canyon Voyage, The Narrative of the Second Powell Expedition down the Green-Colorado River from Wyoming, and the Explorations on Land, in the Years 1871 and 1872"

(1908) by Frederick Samuel Dellenbaugh at Project Gutenberg. *

Powell, J. W., In Fowler, D. D., & In Fowler, C. S. (1971). Anthropology of the Numa: John Wesley Powell's manuscripts on the Numic peoples of Western North America, 1868–1880. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press; for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off..

Fowler, D. D., Matley, J. F., & National Museum of Natural History (U.S.). (1979). Material culture of the Numa: The John Wesley Powell Collection, 1867–1880. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

in the ttp://anthropology.si.edu/cm/ Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution

{{DEFAULTSORT:Powell, John Wesley 1834 births 1902 deaths American explorers Explorers of North America Explorers of the United States American geologists American conservationists Smithsonian Institution people Illinois College alumni Oberlin College alumni People of Illinois in the American Civil War Union Army officers Early Grand Canyon river runners People from Boone County, Illinois Wheaton College (Illinois) alumni Illinois Wesleyan University faculty Illinois State University faculty People from Mount Morris, New York American people of English descent Linguists from the United States United States Geological Survey personnel American civil servants American amputees National Geographic Society founders Burials at Arlington National Cemetery History of the Rocky Mountains Activists from New York (state) Linguists of Hokan languages Members of the American Antiquarian Society Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Linguists of indigenous languages of North America