John Warren Davis (college President) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

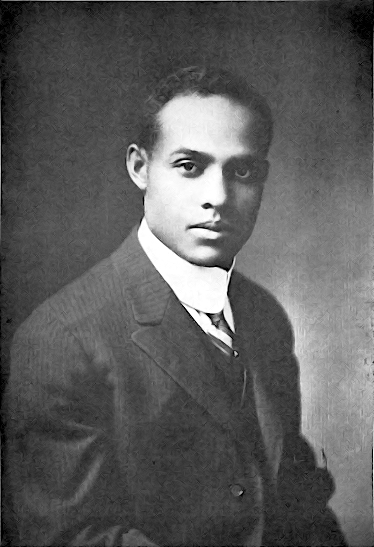

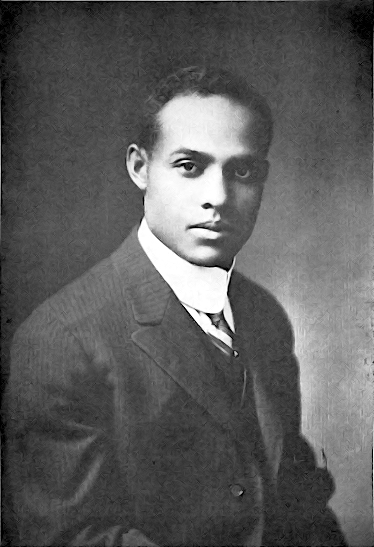

John Warren Davis (February 11, 1888July 12, 1980) was an American educator, college administrator, and civil rights leader. He was the fifth and longest-serving president of

Davis commenced his career in education as a member of the Morehouse faculty, where he served as the registrar from 1914 to 1917, and as a professor of chemistry and physics. Davis also served on the college's standing committee on athletics, and taught physics for the college's academy. In 1915, Davis assisted African American educator and historian

Davis commenced his career in education as a member of the Morehouse faculty, where he served as the registrar from 1914 to 1917, and as a professor of chemistry and physics. Davis also served on the college's standing committee on athletics, and taught physics for the college's academy. In 1915, Davis assisted African American educator and historian

Through Davis' efforts, West Virginia Collegiate Institute became the first African American college to be accredited by the

Through Davis' efforts, West Virginia Collegiate Institute became the first African American college to be accredited by the

Under Davis' leadership in the 1930s, West Virginia State College and its Extension Service were part of a movement to provide educational outdoor and recreational activities for West Virginia's African American youth. This movement received West Virginia Board of Control funding from the

Under Davis' leadership in the 1930s, West Virginia State College and its Extension Service were part of a movement to provide educational outdoor and recreational activities for West Virginia's African American youth. This movement received West Virginia Board of Control funding from the

Also under Davis' leadership, West Virginia State received an Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) unit. He was persistent in conveying the college's desire to have ASTP trainees on its campus. Davis had read about the ASTP in newspapers and in ''School and Safety'', the American Council on Education's weekly newsletter, and he sent a letter on June 16, 1943 to the ASTP Director,

Also under Davis' leadership, West Virginia State received an Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) unit. He was persistent in conveying the college's desire to have ASTP trainees on its campus. Davis had read about the ASTP in newspapers and in ''School and Safety'', the American Council on Education's weekly newsletter, and he sent a letter on June 16, 1943 to the ASTP Director,

Throughout his entire 34-year tenure as president of West Virginia State, Davis resided at East Hall on the college's campus. In 1937, Davis had the house moved from the east side of campus to its current location to make room for a new physical education building. According to Davis' second wife Ethel, the couple held parties on East Hall's large porch, and Ethel held receptions for visiting dignitaries and for freshman and senior students. Guests of the Davises at East Hall included

Throughout his entire 34-year tenure as president of West Virginia State, Davis resided at East Hall on the college's campus. In 1937, Davis had the house moved from the east side of campus to its current location to make room for a new physical education building. According to Davis' second wife Ethel, the couple held parties on East Hall's large porch, and Ethel held receptions for visiting dignitaries and for freshman and senior students. Guests of the Davises at East Hall included

West Virginia State University

West Virginia State University (WVSU) is a public historically black, land-grant university in Institute, West Virginia. Founded in 1891 as the West Virginia Colored Institute, it is one of the original 19 land-grant colleges and universities ...

in Institute, West Virginia

Institute is an unincorporated community on the Kanawha River in Kanawha County, West Virginia, United States. Interstate 64 and West Virginia Route 25 pass by the community, which has grown to intermingle with nearby Dunbar. As of 2018, the commu ...

, a position he held from 1919 to 1953. Born in Milledgeville, Georgia

Milledgeville is a city in and the county seat of Baldwin County in the U.S. state of Georgia. It is northeast of Macon and bordered on the east by the Oconee River. The rapid current of the river here made this an attractive location to buil ...

, Davis relocated to Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

in 1903 to attend high school at Atlanta Baptist College (later known as Morehouse College

, mottoeng = And there was light (literal translation of Latin itself translated from Hebrew: "And light was made")

, type = Private historically black men's liberal arts college

, academic_affiliations ...

). He worked his way through high school and college at Morehouse and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

degree in 1911. At Morehouse, Davis formed associations with John Hope, Mordecai Wyatt Johnson

Mordecai Wyatt Johnson (January 4, 1890 – September 10, 1976) was an American educator and pastor. He served as the first African-American president of Howard University, from 1926 until 1960. Johnson has been considered one of the three lead ...

, Samuel Archer, Benjamin Griffith Brawley

Benjamin Griffith Brawley (April 22, 1882February 1, 1939) was an American author and educator. Several of his books were considered standard college texts, including ''The Negro in Literature and Art in the United States'' (1918) and ''New Survey ...

, Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

, and W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in ...

. He completed graduate studies

Postgraduate or graduate education refers to academic or professional degrees, certificates, diplomas, or other qualifications pursued by post-secondary students who have earned an undergraduate (bachelor's) degree.

The organization and struc ...

in chemistry and physics at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

from 1911 to 1913 and served on the faculty of Morehouse as the registrar and as a professor in chemistry and physics. While in Atlanta, Davis helped to found one of the city's first chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. ...

(NAACP).

Davis served as the executive secretary of the Twelfth Street YMCA in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, from 1917 to 1919 when he was elected as the president of West Virginia Collegiate Institute

West Virginia State University (WVSU) is a public historically black, land-grant university in Institute, West Virginia. Founded in 1891 as the West Virginia Colored Institute, it is one of the original 19 land-grant colleges and universities e ...

. Under his leadership the school, (later renamed West Virginia State College), became one of the leading historically black colleges and universities

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. ...

and land-grant universities in the United States, in both academics and athletics. Through Davis' efforts, West Virginia Collegiate Institute became the first African American college to be accredited by the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools

The North Central Association of Colleges and Schools (NCA), also known as the North Central Association, was a membership organization, consisting of colleges, universities, and schools in 19 U.S. states engaged in educational accreditation. It w ...

(NCA) in 1927. Under his leadership, the college became home to the West Virginia Schools for the Colored Deaf and Blind and to West Virginia's Extension Service library Extension service may refer to:

* Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service (CSREES), a USDA office

* Agricultural extension services, educational services offered to farmers and other growers

* Church extension service ...

for African Americans. Davis also secured a Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) and Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) unit for the college during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Through his efforts and educational statesmanship, Davis laid the groundwork for West Virginia State's transition into an integrated institution, and white students began enrolling in large numbers toward the end of his presidency.

U.S. President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

appointed Davis as a charter member to the first National Science Board for the National Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent agency of the United States government that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. Its medical counterpart is the National I ...

, on which he served from 1950 to 1956. In addition, President Truman appointed Davis as the director of the Technical Cooperation Administration

The Point Four Program was a technical assistance program for "developing countries" announced by United States President Harry S. Truman in his inaugural address on January 20, 1949. It took its name from the fact that it was the fourth foreig ...

program in Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

from 1952 to 1954. Davis helped to establish the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (NAACP LDF), and he served as special director of the NAACP LDF Teacher Information and Security Program from 1955 to 1972. In this role, he administered the NAACP LDF's scholarship programs for African American undergraduate, graduate, and professional students. In his later life, Davis was appointed to the U.S. National Commission for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and served as a member of the Bergen County College board of trustees. Davis continued to work as an active consultant for the NAACP LDF and serve as the head of its Herbert Lehmann Fund until his death in 1980. Davis was a recipient of 14 honorary degrees throughout his lifetime, and he was awarded Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

's National Order of Honour and Merit (1948) and Liberia's Order of the Star of Africa

The Order of the Star of Africa is an order presented by the government of Liberia.

Criteria

The Order of the Star of Africa is presented in five grades, Knight, Officer, Grand Commander, Grand Officer, and Grand Cross. Liberian and foreign ci ...

(1955) for his service to those countries.

Early life and education

John Warren Davis was born on February 11, 1888, inMilledgeville, Georgia

Milledgeville is a city in and the county seat of Baldwin County in the U.S. state of Georgia. It is northeast of Macon and bordered on the east by the Oconee River. The rapid current of the river here made this an attractive location to buil ...

. He was the son of Robert Marion Davis, a merchant, and his wife, Katie Mann Davis. Davis' mother was the biracial daughter of a white pastor. He was raised at his maternal grandfather's home from the age of five, after his parents relocated to Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

, with their other children.

Davis attended elementary school in Milledgeville; however, since there were no public high schools for African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

in the U.S. state of Georgia, Davis relocated to Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

, Georgia, in 1903 to attend Atlanta Baptist College

, mottoeng = And there was light (literal translation of Latin itself translated from Hebrew: "And light was made")

, type = Private historically black men's liberal arts college

, academic_affiliations ...

(later known as Morehouse College). He worked his way through high school and college at Morehouse, and gained the attention of the college's first African American president, John Hope, while polishing the floor of his house. Hope, known as "the maker of college presidents," elevated Davis to a position in the college's business office. Davis completed the school's academic course in 1907 and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

(with honors) in 1911.

While attending Morehouse, Davis was a roommate of Mordecai Wyatt Johnson

Mordecai Wyatt Johnson (January 4, 1890 – September 10, 1976) was an American educator and pastor. He served as the first African-American president of Howard University, from 1926 until 1960. Johnson has been considered one of the three lead ...

, who later served as president of Howard University; they remained longstanding friends. Davis and Johnson both played for Morehouse's football team; Davis was a defensive end

Defensive end (DE) is a defensive position in the sport of gridiron football.

This position has designated the players at each end of the defensive line, but changes in formation (American football), formations over the years have substantially ...

. They befriended Charles H. Wesley

Charles Harris Wesley (December 2, 1891 – August 16, 1987) was an American historian, educator, minister, and author. He published more than 15 books on African-American history, taught for decades at Howard University, and served as president ...

in 1910 while playing for the team. In addition to Hope, Davis was influenced by Morehouse professors Samuel Archer and Benjamin Griffith Brawley

Benjamin Griffith Brawley (April 22, 1882February 1, 1939) was an American author and educator. Several of his books were considered standard college texts, including ''The Negro in Literature and Art in the United States'' (1918) and ''New Survey ...

. Davis attended Morehouse during the ongoing Atlanta Compromise debate between Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

and W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in ...

over the future of African American education. Davis sided with Du Bois in this ideological debate, and he "began to formulate his lifetime philosophies and commitment to the educational development of the black community." Davis received counsel from both Washington and Du Bois, and he remained a lifelong friend of Du Bois.

With Hope's encouragement, Davis completed graduate studies

Postgraduate or graduate education refers to academic or professional degrees, certificates, diplomas, or other qualifications pursued by post-secondary students who have earned an undergraduate (bachelor's) degree.

The organization and struc ...

in chemistry and physics at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

from 1911 to 1913. Davis and other African American students were able to attend the university by working after-hour and summer jobs, which were secured for them by an influential African American benefactor at Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

's Union Stock Yards

The Union Stock Yard & Transit Co., or The Yards, was the meatpacking district in Chicago for more than a century, starting in 1865. The district was operated by a group of railroad companies that acquired marshland and turned it into a central ...

.

Carter G. Woodson

Carter Godwin Woodson (December 19, 1875April 3, 1950) was an American historian, author, journalist, and the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). He was one of the first scholars to study the h ...

in establishing the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History

The Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) is an organization dedicated to the study and appreciation of African-American History. It is a non-profit organization founded in Chicago, Illinois, on September 9, 1915 ...

. He also helped Walter Francis White to found one of the city's first chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. ...

(NAACP).

Throughout his early years in the segregated American South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, Davis overcame racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

, which included being forced out of a Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

town at gunpoint for entering a store that refused service to African Americans, and being prevented from attending an educational conference at Georgia State College by the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

.

In 1917, Davis was hired as the executive secretary of the Twelfth Street Branch of the Young Men's Christian Association

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

(YMCA) in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, by Jesse E. Moorland

Jesse Edward Moorland (September 10, 1863 – April 30, 1940) was an American minister, community executive, civic leader and book collector.

Born in Coldwater, Ohio, he was the only child of a farming family. Moorland attended Northwestern Norma ...

of the YMCA's Colored Men's Department. Davis served in this position until 1919.

President of West Virginia State College

On August 20, 1919, Davis was selected to succeed Byrd Prillerman as the fifth president ofWest Virginia Collegiate Institute

West Virginia State University (WVSU) is a public historically black, land-grant university in Institute, West Virginia. Founded in 1891 as the West Virginia Colored Institute, it is one of the original 19 land-grant colleges and universities e ...

in Institute, West Virginia

Institute is an unincorporated community on the Kanawha River in Kanawha County, West Virginia, United States. Interstate 64 and West Virginia Route 25 pass by the community, which has grown to intermingle with nearby Dunbar. As of 2018, the commu ...

; he commenced his presidency on September 1, 1919. The institute had been founded in 1891 as the West Virginia Colored Institute, under the Morrill Act of 1890

The Morrill Land-Grant Acts are United States statutes that allowed for the creation of land-grant colleges in U.S. states using the proceeds from sales of federally-owned land, often obtained from indigenous tribes through treaty, cession, or se ...

, to provide West Virginia's African Americans with education in agricultural and mechanical studies. Davis was elected as the school's president through his association with Morehouse president John Hope, and a personal recommendation from his friend Carter G. Woodson. While he had no previous experience as an educational administrator, Woodson promised to give him advice and assistance, so Davis accepted the position. Davis then invited Woodson to assist him by serving as the Academic Dean

Dean is a title employed in academic administrations such as colleges or universities for a person with significant authority over a specific academic unit, over a specific area of concern, or both. In the United States and Canada, deans are usua ...

of the institute's college department. Woodson accepted this position because he was grateful to have employment, and the $2,700-per-year salary enabled him to operate his ''Journal of Negro History

''The Journal of African American History'', formerly ''The Journal of Negro History'' (1916–2001), is a quarterly academic journal covering African-American life and history. It was founded in 1916 by Carter G. Woodson. The journal is owned and ...

''. Woodson had been offered the presidency of the West Virginia Collegiate Institute in 1919 but declined due to the administrative duties required to operate a college, as it would have left him with little time to research and write.

Expansion and improvement of the campus and curriculum

Under Davis' leadership, West Virginia Collegiate Institute became one of the leadinghistorically black colleges and universities

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. ...

and land-grant universities in the United States, in both academics and athletics. At the time of Davis' arrival, the institute suffered from depressed academic and physical conditions. He transformed the school's campus during his first ten years of leadership through the construction of new buildings. He also expanded and improved the school's academic programs and curriculum. Davis recruited some of the nation's preeminent African American educators to join the school's faculty. In 1922, Carter G. Woodson described the institute under Davis' leadership as "a reorganized college furnishing facilities for education not offered elsewhere for the youth of West Virginia."

The 1922 ''Biennial Report of the State Supervisor of Negro Schools of West Virginia'' noted "steady and commendable" progress had been made at West Virginia Collegiate Institute under Davis' management. The report stated that a new dormitory for female students had been erected, and many new volumes had been added to the school's library, and it also noted, "this institution is possibly the best equipped State-supported college for Negroes in America." Despite the school's progress under Davis, the report noted the institute's work was hampered by inadequate classroom facilities, and acknowledged the need for "an administration building, a gymnasium, library, and cottages for teachers."

Through Davis' efforts, West Virginia Collegiate Institute became the first African American college to be accredited by the

Through Davis' efforts, West Virginia Collegiate Institute became the first African American college to be accredited by the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools

The North Central Association of Colleges and Schools (NCA), also known as the North Central Association, was a membership organization, consisting of colleges, universities, and schools in 19 U.S. states engaged in educational accreditation. It w ...

(NCA) in 1927. In Davis' annual report for the school in 1927, he stated that the institute was the first ever U.S. college with an African American president and full African American faculty to become fully accredited. Davis later become the first African American member of NCA's Committee on Institutions of Higher Education. West Virginia Collegiate Institute changed its name to West Virginia State College in 1929, and it began conferring college degrees. Soon after this transition, West Virginia State became home to the West Virginia Schools for the Colored Deaf and Blind and to West Virginia's Extension Service library Extension service may refer to:

* Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service (CSREES), a USDA office

* Agricultural extension services, educational services offered to farmers and other growers

* Church extension service ...

for African Americans. Following the integration of West Virginia's graduate schools in 1939, Davis selected the first three African American students to be offered entrance into West Virginia University

West Virginia University (WVU) is a public land-grant research university with its main campus in Morgantown, West Virginia. Its other campuses are those of the West Virginia University Institute of Technology in Beckley, Potomac State College ...

, one of whom was Katherine Johnson

Katherine Johnson (née Coleman; August 26, 1918 – February 24, 2020) was an American mathematician whose calculations of orbital mechanics as a NASA employee were critical to the success of the first and subsequent U.S. crewed spaceflights. ...

.

During his tenure as West Virginia State's president, the college's enrollment increased from around 20 students in 1919 to a peak enrollment of between 1,850 and 1,900 students at the time of his departure in 1953. Through his efforts and educational statesmanship, Davis laid the groundwork for West Virginia State's transition into an integrated institution. Davis supported the desegregation of schools over further equalization of African American institutions, and in 1946, he stated, "Negro education postulates doctrines of minimization of personality, social and economic mediocrity, and second class citizenship. The remaining task for it is to die. The aim of all segregated institutions should be to work themselves out of a job." Under Davis, West Virginia State began enrolling white students before 1950, in violation of state law, and it became the first historically black college to enroll large numbers of white students. White students began entering West Virginia State in increasing numbers during the final years of Davis' presidency, and the college ceased having a majority of African American students. By 1965, white students accounted for 71 percent of the college's enrollment. Davis resigned his position as president of the college in 1953, and was elected president emeritus of West Virginia State following his departure.

Early African American educational history of West Virginia

Davis initiated a study of early African American educational history in West Virginia and appointed a committee to undertake the study's research and data collection. Carter G. Woodson served as the committee's chairperson and developed a questionnaire that was disseminated among West Virginia's African American communities and institutions to gather facts. At the conclusion of this study, Davis held a presentation of its findings as part of the West Virginia Collegiate Institute Founder's Day celebration on May 3, 1921. Many of the living pioneers of early African American education in West Virginia were invited to address this meeting to share their experiences. In 1922, Woodson published the study's findings in the article, "Early Negro Education in West Virginia," in his ''Journal of Negro History''. In 1922, Woodson began receiving a grant from theCarnegie Corporation of New York

The Carnegie Corporation of New York is a philanthropic fund established by Andrew Carnegie in 1911 to support education programs across the United States, and later the world. Carnegie Corporation has endowed or otherwise helped to establis ...

for the operation of his ''Journal of Negro History'' and shortly thereafter, he resigned his position as dean of the West Virginia Collegiate Institute in June of that year. Davis accepted Woodson's resignation, and while he was disappointed in his decision, he understood Woodson's devotion to promoting African American history.

Extension Service and State 4-H Camp for African Americans

Under Davis' leadership in the 1930s, West Virginia State College and its Extension Service were part of a movement to provide educational outdoor and recreational activities for West Virginia's African American youth. This movement received West Virginia Board of Control funding from the

Under Davis' leadership in the 1930s, West Virginia State College and its Extension Service were part of a movement to provide educational outdoor and recreational activities for West Virginia's African American youth. This movement received West Virginia Board of Control funding from the Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, i ...

(WPA) when the West Virginia Legislature established Camp Washington-Carver in 1937 near Clifftop in Fayette County. The African American 4-H

4-H is a U.S.-based network of youth organizations whose mission is "engaging youth to reach their fullest potential while advancing the field of youth development". Its name is a reference to the occurrence of the initial letter H four times i ...

camp was constructed by the WPA between 1939 and 1942 and under Davis' leadership. The camp was transferred from the West Virginia Board of Control to West Virginia State's Extension Service in 1942. Camp Washington-Carver was formally dedicated on July 26, 1942 in a ceremony attended by Davis. At the 4-H camp, West Virginia State's Extension Service offered instruction to African American children and adolescents in the subjects of agricultural education, soil conservation, home economics, and 4-H values. Later in 1949, the West Virginia Conservation Commission consulted Davis on the name for a state recreational area for African Americans near Institute, and following his recommendation, the Conservation Commission selected the name, Booker T. Washington State Park.

Civilian Pilot Training Program

Davis began pursuing a pilot training program for West Virginia State in 1934 through a cooperative relationship between the college's vocational program and officials at nearby Wertz Field, adjacent to the campus. Following the outbreak ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in 1939, the United States government recognized a shortage of trained pilots. To mitigate this shortage, its Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) established the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) with the intention of creating pilot training programs at U.S. colleges and universities. According to West Virginia State's Dr. Charles Ledbetter, only 20 African Americans in the U.S. were licensed as pilots at the time of the CPTP's establishment. On September 11, 1939, Davis received approval from the CAA to establish a CPTP at West Virginia State—the first African American college in the U.S. to do so. Its CPTP was announced on September 18, along with that of the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina. West Virginia State's CPTP conducted flight instruction at nearby Wertz Field. In October 1939, Davis coordinated with the National Youth Administration to secure a mechanic work experience project as part of West Virginia State's CPTP.

One of the college's CPTP instructors, Dr. Charles Byrd, noted that West Virginia State's CPTP "played a part in the struggle to get African Americans accepted" into the United States Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. After World War I, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical r ...

(USAAC). When the USAAC admitted the first African Americans and organized the 99th Flying Training Squadron

The 99th Flying Training Squadron (99 FTS) flies Raytheon T-1 Jayhawks and they have painted the tails of their aircraft red in honor of the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II fame, known as the "Red Tails," whose lineage the 99 FTS inherited.

The ...

, two of the first five commissioned African American pilots were graduates from West Virginia State's CPTP: George Spencer Roberts, the first African American appointed to the USAAC and Mac Ross. Another of the college's CPTP graduates was Rose Agnes Rolls of Fairmont, West Virginia

Fairmont is a city in and county seat of Marion County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 18,313 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Fairmont Micropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Marion County, a ...

, the first African American woman to receive flight training through the CAA and the first female solo pilot in the CPTP nationwide. Rolls and Joseph Greider, a West Virginia State music professor, later joined the West Virginia Civil Air Patrol, becoming the first African Americans in the state's air patrol. In the summer of 1940, West Virginia State became the first African American college to enroll white trainees into its CPTP. This served as a precedent for the racial integration

Racial integration, or simply integration, includes desegregation (the process of ending systematic racial segregation). In addition to desegregation, integration includes goals such as leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportunity ...

of the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

. West Virginia State's CPTP was discontinued in 1942.

Army Specialized Training Program

Also under Davis' leadership, West Virginia State received an Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) unit. He was persistent in conveying the college's desire to have ASTP trainees on its campus. Davis had read about the ASTP in newspapers and in ''School and Safety'', the American Council on Education's weekly newsletter, and he sent a letter on June 16, 1943 to the ASTP Director,

Also under Davis' leadership, West Virginia State received an Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) unit. He was persistent in conveying the college's desire to have ASTP trainees on its campus. Davis had read about the ASTP in newspapers and in ''School and Safety'', the American Council on Education's weekly newsletter, and he sent a letter on June 16, 1943 to the ASTP Director, United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

Colonel Herman Beukema. Beukema responded by stating that the ASTP was using Howard University, Prairie View State College

Prairie View A&M University (PVAMU or PV) is a public historically black land-grant university in Prairie View, Texas. Founded in 1876, it is one of Texas's two land-grant universities and the second oldest public institution of higher learning ...

, and Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina, which met current demands. He added that the army planned to give the college "an Army Specialized Training Unit at the earliest possible date."

Davis was only made aware that West Virginia State was receiving an ASTP unit two weeks before ASTP personnel arrived on its campus. On July 16, 1943, Colonel W. G. Johnston of the Army Service Forces

The Army Service Forces was one of the three autonomous components of the United States Army during World War II, the others being the Army Air Forces and Army Ground Forces, created on 9 March 1942. By dividing the Army into three large comman ...

' Fifth Service Command called Davis to inform him, and two days later, Johnston confirmed the tentative number of ASTP trainees, arrival date, and basic engineering courses to be offered, and that a contract "negotiating party" would soon visit the campus. Within a week's time, West Virginia State reached agreements with the Fifth Service Command, and Davis commenced modifications to the college's Gore Hall, where most of the ASTP personnel were housed. On July 22, 1943, Davis wrote to Johnston, requesting him to expand the anticipated total of 150 trainees to 300, an amount that included 17-year-old West Virginia reservists who were to attend ASTP training at other colleges and universities. In this letter, Davis assured Johnston, "the entire force of this college ... is now busy preparing for the arrival of AST trainees."

Nonpartisan leadership style

Throughout his tenure as president of West Virginia State, Davis was able to govern the college with a surprising degree of independence and political nonpartisanship, despite its proximity to thestate capitol

This is a list of state and territorial capitols in the United States, the building or complex of buildings from which the government of each U.S. state, the District of Columbia and the organized territories of the United States, exercise its ...

in nearby Charleston. In a 1944 meeting of the West Virginia State faculty, Davis explained his disinterest in partisan politics to the college's faculty: "I have never felt it my duty to go and dabble in partisan politics. I hold the position that I have a unique place in the life of the state. You and I are to cooperate in guiding this school, that whatever party is in power, the success of the institution can be a credit to that party." However, Davis advocated the college's advancement in all matters in his correspondences with West Virginia state legislators and officials. He also leveraged his faculty as a resource for providing expertise and assistance to state politicians, regardless of their party. When a West Virginia state senator expressed an interest in having German papers translated, Davis recommended a West Virginia State faculty member to perform this task, and he assured the senator that the professor would remain "quiet" about their assistance. Davis believed that assistance provided by West Virginia State would be returned in the form of appropriations. Author Gerald L. Smith cited Davis' nonpartisan leadership style as being an influence on Rufus B. Atwood, president of Kentucky State College. Davis was also able to secure appropriations for the West Virginia State's buildings and equipment because the state's Democratic and Republican parties both vied for African American votes.

Associated Publishers, Inc.

In June 1921, Davis and African American leaders including Carter G. Woodson, Don S.S. Goodloe, Mordecai Wyatt Johnson, and Byrd Prillerman, established Associated Publishers, Inc., in Washington, D.C., with a capital stock of $25,000. Davis and his fellow incorporators founded the firm after recognizing the need of "supplanting exploiting publishers" and to focus primarily on works by African American authors and on issues concerning the African American community. Davis served as the publishing firm's treasurer and Woodson served as its president.United States Government service

Throughout his lifetime, Davis was an adviser to five United States presidents, and he served in multiple roles in support of theUnited States federal government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the Federation#Federal governments, national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 ...

. He served as a member of the National Advisory Committee on Education of Negroes in 1929 and again from 1948 to 1951. In 1931, Davis was appointed a member of the President's Organization for Unemployment Relief The President's Organization for Unemployment Relief (originally known as the President's Emergency Committee for Employment) was a government organization created on August 19, 1931, by United States President Herbert Hoover. Its commission was to ...

under President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

. At the invitation of United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ...

, Davis participated in a conference on Inter-American relations in November 1939. In August 1941, Davis accepted an invitation from U.S. Treasury Secretary

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

Henry Morgenthau Jr.

Henry Morgenthau Jr. (; May 11, 1891February 6, 1967) was the United States Secretary of the Treasury during most of the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt. He played a major role in designing and financing the New Deal. After 1937, while ...

to serve on West Virginia's Defense Savings Committee, which was responsible for promoting the purchase of savings bonds A savings bond is a government bond designed to provide funds for the issuer while also providing a relatively safe investment for the purchaser to save money, typically a retail investor. The earliest savings bonds were the war bond programs of Wor ...

to finance national defense efforts. Following the passage of the National Science Foundation Act of 1950, President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

appointed Davis as a charter member to the first National Science Board for the National Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent agency of the United States government that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. Its medical counterpart is the National I ...

, on which he served from 1950 to 1956. Davis was also chairperson of the National Commission for the Defense of Democracy through Education.

In his final year as president of West Virginia State, Davis took a permanent leave of absence to embark on a career in foreign service. President Truman appointed him to serve, under the first African American United States Ambassador Edward R. Dudley, as the director of the Technical Cooperation Administration

The Point Four Program was a technical assistance program for "developing countries" announced by United States President Harry S. Truman in his inaugural address on January 20, 1949. It took its name from the fact that it was the fourth foreig ...

program in Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

from 1952 to 1954. Davis served as a consultant to the Peace Corps

The Peace Corps is an independent agency and program of the United States government that trains and deploys volunteers to provide international development assistance. It was established in March 1961 by an executive order of President John F. ...

in 1961, and as a consultant on minority hiring to the United States Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other n ...

's United States Information Agency

The United States Information Agency (USIA), which operated from 1953 to 1999, was a United States agency devoted to "public diplomacy". In 1999, prior to the reorganization of intelligence agencies by President George W. Bush, President Bill C ...

.

Civil Rights Movement

Davis was among thevanguard

The vanguard (also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

History

The vanguard derives fr ...

of the American Civil Rights Movement. He was active in the National Urban League and served on its executive board. Davis also advised George Edmund Haynes and Eugene Kinckle Jones

Eugene Kinckle Jones (July 30, 1885 – January 11, 1954) was a leader of the National Urban League and one of the seven founders (''commonly referred to as Seven Jewels'') of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity at Cornell University in 1906. Jones ...

on the league's development. In 1928, he served as the president of the National Association of Teachers in Colored Schools

The American Teachers Association (1937-1966), formerly National Colored Teachers Association (1906–1907) and National Association of Teachers in Colored Schools (1907–1937), was a professional association and teachers' union representing tea ...

(later known as the American Teachers Association). While Davis had not sought this leadership position, his peers believed he had the necessary leadership qualities to head the association during a pivotal time in African American education. In 1934, Davis wrote a pamphlet entitled, "Land-Grant Colleges for Negroes," for the ''West Virginia State College Bulletin'' and continued to expand this article into a book. He died in 1980 before it could be published.

Davis helped to establish the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (NAACP LDF), and he was elected to serve on its Board of Directors, two days after its inception in 1939. After accepting an invitation by Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme Court's first African-A ...

in 1955, Davis served as the special director of the NAACP LDF Teacher Information and Security Program, which he established to preserve the positions of African American educators. While at the NAACP LDF, Davis worked closely with Marshall, the fund's Chief Counsel, to prepare for the '' Brown v. Board of Education'' case. This case resulted in the landmark

A landmark is a recognizable natural or artificial feature used for navigation, a feature that stands out from its near environment and is often visible from long distances.

In modern use, the term can also be applied to smaller structures or f ...

decision of the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

in public schools

Public school may refer to:

*State school (known as a public school in many countries), a no-fee school, publicly funded and operated by the government

*Public school (United Kingdom), certain elite fee-charging independent schools in England and ...

are unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools are otherwise equal in quality.

In his role as the special director of the NAACP LDF Teacher Information and Security Program, Davis fought for the protection of African American teachers, and for communities making the transition into integrated schools. Davis administered the NAACP LDF's scholarship programs for African American undergraduate, graduate, and professional students. During his 24 years in this role, the NAACP LDF provided more than 1,300 scholarships and grants to African American students. In 1964, Davis became the special director for the Herbert Lehman Educational Fund. He later became a consultant to the NAACP LDF in 1972 and served in this position until his death in 1980.

Davis was a close friend of Mary McLeod Bethune

Mary Jane McLeod Bethune ( McLeod; July 10, 1875 – May 18, 1955) was an American educator, philanthropist, humanitarian, Womanism, womanist, and civil rights activist. Bethune founded the National Council of Negro Women in 1935, established th ...

, founder of the National Council of Negro Women. He accompanied her on her first visit to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

for her presentation on the problems facing African Americans to President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

.

Later life and death

Davis and his wife relocated toEnglewood, New Jersey

Englewood is a city in Bergen County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey, which at the 2020 United States census had a population of 29,308. Englewood was incorporated as a city by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on March 17, 1899, from por ...

, in 1954 following his departure from West Virginia State. In 1960, Davis was appointed to the United States National Commission for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

He became a member of the Bergen County College board of trustees, and at the college's first annual commencement exercise in 1970, Davis delivered a speech against the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

in which he stated, "More than 42,000 young men of this nation have died in an undeclared war. No nation will win the Vietnam War and our continued participation in this war will weaken the vitality of America and destroy its substance." In his speech, Davis also challenged the graduates to, "Bring our peoples together, black and white, and repair the cracked Liberty Bell

The Liberty Bell, previously called the State House Bell or Old State House Bell, is an iconic symbol of American independence, located in Philadelphia. Originally placed in the steeple of the Pennsylvania State House (now renamed Independence ...

so that it can clearly and loudly proclaim liberty throughout the land."

In May 1973, Davis delivered the graduation commencement address at West Virginia State College, in which he told graduates that it was up to them to see that no more Watergates occur. Davis attended the first Seminar on Black Colleges and Universities in Nashville

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and the ...

in November 1979 and participated in its study group to discuss the future missions of black colleges and universities.

Davis continued to work as an active consultant for the NAACP LDF and serve as the head of its Herbert Lehmann Fund until his death. He died of a heart attack at the age of 92 at his home in Englewood on July 12, 1980. A memorial service for Davis was held on July 18, 1980 at the First Baptist Church in Englewood. At the time of his death, Davis was engaged in a survey of all the United States African American land-grant colleges and universities.

Personal life

Marriages and children

In 1916, Davis married Bessie Rucker (born July 13, 1890), the daughter of Georgia politician Henry Allan Rucker (1852–1924) and his wife, Annie Long Rucker (1865–1933). Rucker's father served as head of revenue collection in Georgia during theReconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

, and her maternal grandfather, Jefferson F. Long

Jefferson Franklin Long (March 3, 1836 – February 4, 1901) was a U.S. congressman from Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. He was the second African American sworn into the U.S. House of Representatives and the first African-American congressman ...

(1836–1901), was Georgia's first African American congressperson in the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

. Davis and his first wife Bessie had two daughters: Constance Rucker Davis Welch and Dorothy Long Davis McDaniel.

Following several months of illness, Bessie Rucker Davis died of hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer in adults and is currently the most common cause of death in people with cirrhosis. HCC is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide.

It occurs in t ...

on February 24, 1931 at Mountain State Hospital in Charleston at the age of 40, with her husband and sister Lucy Rucker Aiken at her bedside. Davis, his daughters Constance and Dorothy, and numerous friends and faculty from West Virginia State College, traveled together to Atlanta for the memorial service. Her funeral was held at the Rucker family home in Atlanta and featured a violin solo by Kemper Harreld. Bessie Rucker Davis was interred

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and objec ...

at Atlanta's Oakland Cemetery.

On September 2, 1932, Davis married Ethel Elizabeth McGhee, an educator and activist for African American social advancement, and dean of women The dean of women at a college or university in the United States is the dean with responsibility for student affairs for female students. In early years, the position was also known by other names, including preceptress, lady principal, and adviser ...

at Spelman College. Davis and McGhee were married in Englewood, New Jersey, after which, she resigned her position at Spelman and relocated to West Virginia State with Davis. Davis and McGhee had one daughter together: Caroline "Dash" Florence Davis Gleiter (November 19, 1933 – January 26, 2004).

Residences

Throughout his entire 34-year tenure as president of West Virginia State, Davis resided at East Hall on the college's campus. In 1937, Davis had the house moved from the east side of campus to its current location to make room for a new physical education building. According to Davis' second wife Ethel, the couple held parties on East Hall's large porch, and Ethel held receptions for visiting dignitaries and for freshman and senior students. Guests of the Davises at East Hall included

Throughout his entire 34-year tenure as president of West Virginia State, Davis resided at East Hall on the college's campus. In 1937, Davis had the house moved from the east side of campus to its current location to make room for a new physical education building. According to Davis' second wife Ethel, the couple held parties on East Hall's large porch, and Ethel held receptions for visiting dignitaries and for freshman and senior students. Guests of the Davises at East Hall included Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

, Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1901 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary art form called jazz poetry, Hug ...

, W.E.B. Du Bois, George Washington Carver

George Washington Carver ( 1864 – January 5, 1943) was an American agricultural scientist and inventor who promoted alternative crops to cotton and methods to prevent soil depletion. He was one of the most prominent black scientists of the ea ...

, and Ralph Bunche

Ralph Johnson Bunche (; August 7, 1904 – December 9, 1971) was an American political scientist, diplomat, and leading actor in the mid-20th-century decolonization process and US civil rights movement, who received the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize f ...

. The Davises continued to reside at East Hall while it was being moved across campus. After relocating to Englewood, New Jersey, with his wife in 1954, Davis resided there for 26 years until his death in 1980.

Honors and awards

Honorary degrees

Davis was a recipient of 14 honorary degrees, including the degrees listed below. Davis also received honorary doctorates from West Virginia State College andHarvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

.

Orders and fraternities

In 1948, Davis was awarded the National Order of Honour and Merit,Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

's highest order of merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by K ...

awarded by its president, for "increasing the understanding and good will existing between Haiti and the United States of America." He was awarded the Order of the Star of Africa

The Order of the Star of Africa is an order presented by the government of Liberia.

Criteria

The Order of the Star of Africa is presented in five grades, Knight, Officer, Grand Commander, Grand Officer, and Grand Cross. Liberian and foreign ci ...

by Liberia in 1955 for strengthening the "bonds of friendship" between Liberia and the U.S.

Davis was a member of the Sigma Pi Phi and Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal a ...

honor society fraternities, and he was a 33rd Degree

The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry (the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction in the United States often omits the ''and'', while the English Constitution in the United Kingdom omits the ''Scottish''), commonly known as simply the Sco ...

Mason and a Prince Hall Mason.

Awards

Davis was awarded theWilliam E. Harmon Foundation Award for Distinguished Achievement Among Negroes #REDIRECT William E. Harmon Foundation Award for Distinguished Achievement Among Negroes

{{R from move ...

for education in 1926. Just prior to his death in 1980, he was honored by the National Education Association (of which he was a member) with its Harper Council Trenholm Award.

Legacy

Davis' lifelong personal and professional pursuits were focused on the economic and educational development of the African American community, the improvement of relations between African Americans and other groups, and the improvement of relations between the United States and developing black nations. With a tenure spanning 34 years, Davis is the longest-serving president of West Virginia State College, which became West Virginia State University in 2004. The university's Davis Fine Arts Building is named in his honor; he delivered the principal address at its public dedication in 1965. Hugh M. Gloster, president of Morehouse College, hailed Davis as "one of the outstanding American leaders of the twentieth century." In ''Black Colleges and Universities: Challenges for the Future'' (1984), editor Antoine Garibaldi remarked of Davis' involvement with the book's preparation:Even at 92,avis Avis is Latin for bird and may refer to: Aviation *Auster Avis, a 1940s four-seat light aircraft developed from the Auster Autocrat (abandoned project) *Avro Avis, a two-seat biplane *Scottish Aeroplane Syndicate Avis, an early aircraft built by ...was still progressive in his thinking and believed as strongly as any member of the group that black colleges would have to alter their missions to adapt to a changing clientele of students, changing demographics and political trends, and economic conditions that have adversely affected the financial health of most institutions of higher learning. Dr. Davis leaves a legacy for all educators to emulate. He will be missed by all those who had the good fortune to know him, but his contributions to education, to civil rights, and to the United States will live on.

Selected works

* * * *References

Explanatory notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Davis, John Warren 1888 births 1980 deaths 19th-century African-American people 20th-century African-American educators Academics from Georgia (U.S. state) Academics from West Virginia African-American publishers (people) American academic administrators American expatriates in Liberia Educators from Georgia (U.S. state) Educators from West Virginia Morehouse College alumni Morehouse College faculty NAACP activists National Education Association people People from Atlanta People from Englewood, New Jersey People from Institute, West Virginia People from Milledgeville, Georgia Educators from Washington, D.C. Presidents of West Virginia State University UNESCO officials United States Department of State officials United States National Science Foundation officials University of Chicago alumni YMCA leaders 20th-century American academics 20th-century African-American academics African-American academic administrators