John W. Stevenson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

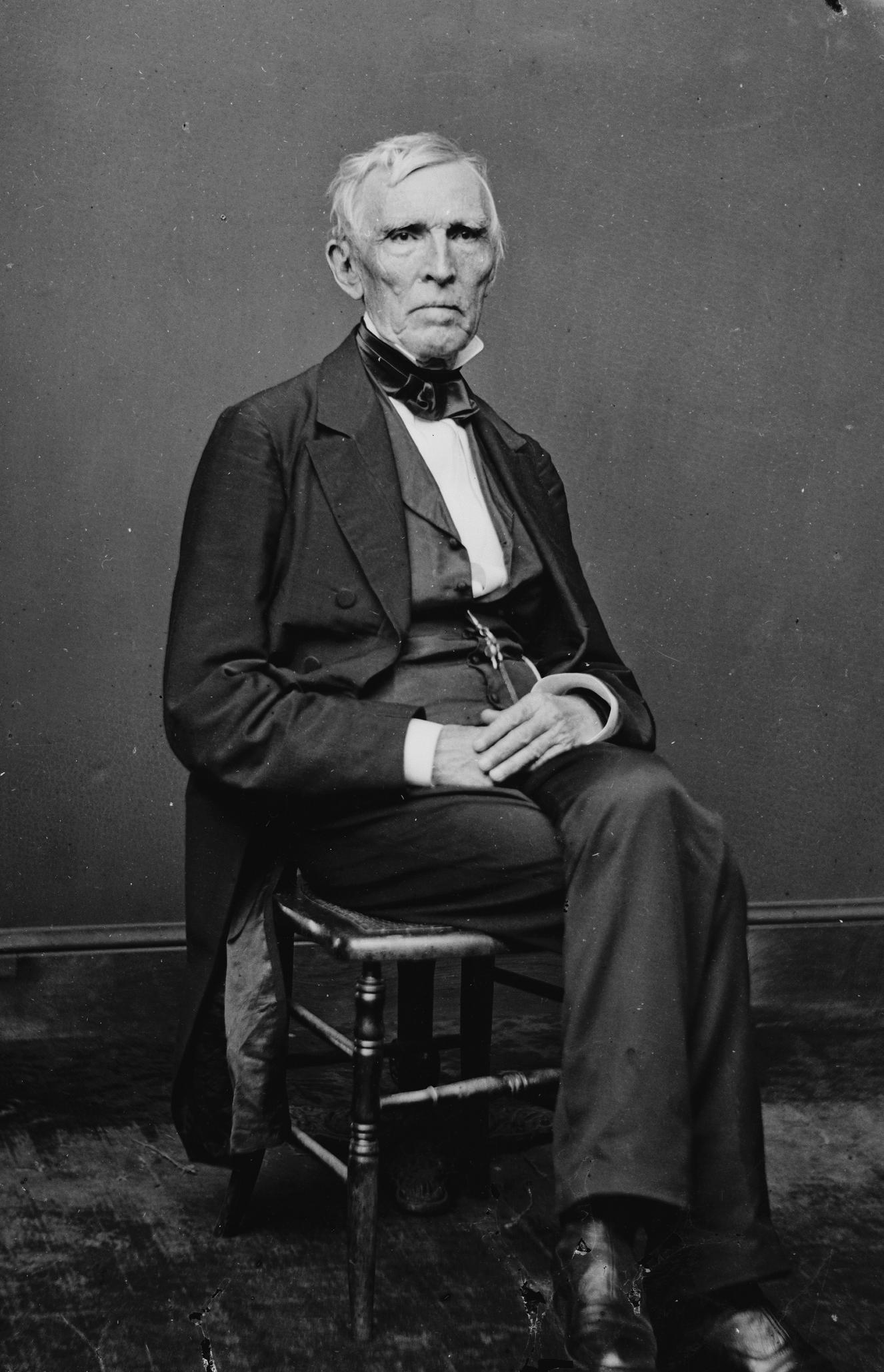

John White Stevenson (May 4, 1812August 10, 1886) was the 25th governor of Kentucky and represented the state in both houses of the

Like many Kentuckians, Stevenson was sympathetic to the southern states' position in the lead-up to the

Like many Kentuckians, Stevenson was sympathetic to the southern states' position in the lead-up to the

Ex-Confederates dominated the Kentucky Democratic convention that met in Frankfort on February 22, 1867. John L. Helm, father of the late Confederate general Benjamin Hardin Helm, was nominated for governor and Stevenson was nominated for

Ex-Confederates dominated the Kentucky Democratic convention that met in Frankfort on February 22, 1867. John L. Helm, father of the late Confederate general Benjamin Hardin Helm, was nominated for governor and Stevenson was nominated for

Text of Stevenson's protest to Congress for failing to seat the entire Kentucky delegation

(pages 2162 to 2171) , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Stevenson, John W. 1812 births 1886 deaths 19th-century American Episcopalians 19th-century American politicians American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law Burials at Spring Grove Cemetery Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Kentucky Democratic Party governors of Kentucky Democratic Party United States senators from Kentucky Kentucky lawyers Lieutenant Governors of Kentucky Democratic Party members of the Kentucky House of Representatives Mississippi lawyers Politicians from Covington, Kentucky Politicians from Richmond, Virginia Presidents of the American Bar Association 1852 United States presidential electors 1856 United States presidential electors University of Virginia alumni 19th-century American lawyers

U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

. The son of former Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hungerf ...

and U.S. diplomat Andrew Stevenson

Andrew Stevenson (January 21, 1784 – January 25, 1857) was an American politician, lawyer and diplomat. He represented Richmond, Virginia in the Virginia House of Delegates and eventually became its speaker before being elected to the United S ...

, John Stevenson graduated from the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

in 1832 and studied law under his cousin, future Congressman

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivalen ...

Willoughby Newton

Willoughby Newton (December 2, 1802 – May 23, 1874) was a nineteenth-century congressman and lawyer from Virginia.

Biography

Born at "Lee Hall" near Hague, Virginia, he was the son of Willoughby Newton and Sarah "Sally" Bland Poythress (176 ...

. After briefly practicing law in Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, he relocated to Covington, Kentucky

Covington is a list of cities in Kentucky, home rule-class city in Kenton County, Kentucky, Kenton County, Kentucky, United States, located at the confluence of the Ohio River, Ohio and Licking River (Kentucky), Licking Rivers. Cincinnati, Ohio, ...

, and was elected county attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or state attorney is the chief prosecutor and/or chief law enforcement officer representing a U.S. state in a loc ...

. After serving in the Kentucky legislature

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The General Assembly meets annually in t ...

, he was chosen as a delegate to the state's third constitutional convention in 1849 and was one of three commissioners charged with revising its code of laws, a task finished in 1854. A Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

, he was elected to two consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives where he supported several proposed compromises to avert the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

and blamed the Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as " Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reco ...

for their failure.

After losing his reelection bid in 1861, Stevenson, a known Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

sympathizer, stayed out of public life during the war and was consequently able to avoid being imprisoned, as many other Confederate sympathizers were. In 1867, just five days after John L. Helm and Stevenson were elected governor and lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

, respectively, Helm died and Stevenson became acting governor. Stevenson subsequently won a special election in 1868 to finish Helm's term. As governor, he opposed federal intervention in what he considered state matters but insisted that blacks' newly granted rights be observed and used the state militia to quell post-war violence in the state. Although a fiscal conservative, he advocated a new tax to benefit education and created the state bureau of education.

In 1871, Stevenson defeated incumbent Thomas C. McCreery

Thomas Clay McCreery (December 12, 1816July 10, 1890) was a Democratic Party (United States), Democratic United States Senate, U.S. Senator from Kentucky.

Born at Yelvington, Kentucky, McCreery graduated from Centre College, in Danville, Kentu ...

for his seat in the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

after criticizing McCreery for allegedly supporting the appointment of Stephen G. Burbridge, who was hated by most Kentuckians, to a federal position. In the Senate, he opposed internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

and defended a constructionist view of the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

, resisting efforts to expand the powers expressly granted in that document. Beginning in late 1873, Stephenson functioned as the first chairman (later called floor leader

In politics, floor leaders, also known as a caucus leader, are leaders of their respective political party in a body of a legislature.

Philippines

In the Philippines each body of the bicameral Congress has a majority floor leader and a minor ...

) of the Senate Democratic caucus

The Democratic Caucus of the United States Senate, sometimes referred to as the Democratic Conference, is the formal organization of all senators who are part of the Democratic Party in the United States Senate. For the makeup of the 117th Cong ...

. He did not seek reelection in 1877, returning to his law practice and accepting future Kentucky Governor William Goebel

William Justus Goebel (January 4, 1856 – February 3, 1900) was an American Democratic politician who served as the 34th governor of Kentucky for four days in 1900, having been sworn in on his deathbed a day after being shot by an assassin. ...

as a law partner. He chaired the 1880 Democratic National Convention

The 1880 Democratic National Convention was held June 22 to 24, 1880, at the Music Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio, and nominated Winfield S. Hancock of Pennsylvania for president and William H. English of Indiana for vice president in the United Stat ...

and was elected president of the American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of acad ...

in 1884. He died in Covington on August 10, 1886, and was buried in Spring Grove Cemetery

Spring Grove Cemetery and Arboretum () is a nonprofit rural cemetery and arboretum located at 4521 Spring Grove Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio. It is the third largest cemetery in the United States, after the Calverton National Cemetery and Abraham L ...

at Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

.

Early life and family

John White Stevenson was born May 4, 1812, inRichmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. He was the only child of Andrew

Andrew is the English form of a given name common in many countries. In the 1990s, it was among the top ten most popular names given to boys in List of countries where English is an official language, English-speaking countries. "Andrew" is freq ...

and Mary Page (White) Stevenson. His mother—the granddaughter of Carter Braxton

Carter Braxton (September 10, 1736October 10, 1797) was a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence, a merchant, planter, a Founding Father of the United States and a Virginia politician. A grandson of Robert "King" Carter, one of ...

, a signer of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

—died during childbirth. Stevenson was sent to live with his maternal grandparents, John and Judith White, until he was eleven; by then, his father had remarried. His father, a prominent Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

lawyer, rose to political prominence during Stevenson's childhood. He was elected to Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

, eventually serving as Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hungerf ...

and was later appointed Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Court of St. James's (now called the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom

The United States ambassador to the United Kingdom (known formally as the ambassador of the United States to the Court of St James's) is the official representative of the president of the United States and the Federal government of the United S ...

) by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (Uni ...

, where he engendered much controversy by his pro-slavery practices. Because of his father's position, young Stevenson had met both Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

and James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

.

Stevenson was educated by private tutors in Virginia and Washington, D.C., where he frequently lived while his father was in Congress. In 1828, at the age of 14, he matriculated from the Hampden–Sydney Academy (now Hampden–Sydney College

gr, Ye Shall Know the Truth

, established =

, type = Private liberal arts men's college

, religious_affiliation = Presbyterian Church (USA)

, endowment = $258 million (2021)

, president = Larry Stimpert

, city = Hampden Sydney, Virginia

, cou ...

). Two years later, he transferred to University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

, where he graduated in 1832. After graduation, he read law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under the ...

with his cousin, Willoughby Newton

Willoughby Newton (December 2, 1802 – May 23, 1874) was a nineteenth-century congressman and lawyer from Virginia.

Biography

Born at "Lee Hall" near Hague, Virginia, he was the son of Willoughby Newton and Sarah "Sally" Bland Poythress (176 ...

, who would later serve in the U.S. Congress. In 1839, Stevenson was admitted to the bar

An admission to practice law is acquired when a lawyer receives a license to practice law. In jurisdictions with two types of lawyer, as with barristers and solicitors, barristers must gain admission to the bar whereas for solicitors there are dist ...

in Virginia.

Following Madison's advice, Stevenson decided to settle in the west. He traveled on horseback through the western frontier until he reached the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, settling at Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg is a historic city in Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is the county seat, and the population at the 2010 census was 23,856.

Located on a high bluff on the east bank of the Mississippi River across from Louisiana, Vic ...

. Vicksburg was a small settlement at the time and did not provide enough work to satisfy him, and, in 1840, he decided to travel to Covington, Kentucky

Covington is a list of cities in Kentucky, home rule-class city in Kenton County, Kentucky, Kenton County, Kentucky, United States, located at the confluence of the Ohio River, Ohio and Licking River (Kentucky), Licking Rivers. Cincinnati, Ohio, ...

, settling there permanently in 1841. In Covington, he formed a law partnership with Jefferson Phelps, a respected lawyer in the area; the partnership lasted until Phelps' death in 1843.

A devout Episcopalian

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the l ...

, Stevenson frequently attended the conventions of that denomination. He was elected as a vestry

A vestry was a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government for a parish in England, Wales and some English colonies which originally met in the vestry or sacristy of the parish church, and consequently became known colloquiall ...

man of the Trinity Episcopal Church in Covington on November 24, 1842. In 1843, he married Sibella Wilson of Newport, Kentucky

Newport is a list of Kentucky cities, home rule-class city at the confluence of the Ohio River, Ohio and Licking River (Kentucky), Licking rivers in Campbell County, Kentucky, Campbell County, Kentucky. The population was 15,273 at the 2010 United ...

. They had five children: Sally C. (Stevenson) Colston, Mary W. (Stevenson) Colston, Judith W. (Stevenson) Winslow, Samuel W. Stevenson, and John W. Stevenson.Morton gives both Mary and John Stevenson's middle initials as "D." instead of "W." She also omits Samuel W. Stevenson from the list of children, including instead Andrew Stevenson of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She later writes that Stevenson was survived by six children, despite having previously listed only five names. Vaux (p. 14) lists sons Andrew and John, although he states that Andrew lives in Montana. Vaux also mentions three unnamed daughters.

Political career

Soon after arriving in Covington, Stevenson was electedcounty attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or state attorney is the chief prosecutor and/or chief law enforcement officer representing a U.S. state in a loc ...

for Kenton County

Kenton County is a county located in the northern part of the Commonwealth of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 169,064, making it the third most populous county in Kentucky (behind Jefferson County and Fayette County). Its ...

. He was chosen as a delegate to the 1844 Democratic National Convention

The 1844 Democratic National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held in Baltimore, Maryland from May 27 through 30. The convention nominated former Governor James K. Polk of Tennessee for president and former Senator George M. Dal ...

and was elected to represent Kenton County in the Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form ...

the following year. He was reelected in 1846 and 1848. In 1849, he was chosen as a delegate to the state constitutional convention that produced Kentucky's third state constitution. In 1850, he, Madison C. Johnson, and James Harlan were appointed as commissioners to revise Kentucky's civic and criminal code. Their work, ''Code of Practise in Civil and Criminal Cases'' was published in 1854. He was again one of Kentucky's delegates to the Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 1852 ...

s in 1848

1848 is historically famous for the wave of revolutions, a series of widespread struggles for more liberal governments, which broke out from Brazil to Hungary; although most failed in their immediate aims, they significantly altered the polit ...

, 1852

Events

January–March

* January 14 – President Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte proclaims a new constitution for the French Second Republic.

* January 15 – Nine men representing various Jewish charitable organizations come tog ...

, and 1856

Events

January–March

* January 8 – Borax deposits are discovered in large quantities by John Veatch in California.

* January 23 – American paddle steamer SS ''Pacific'' leaves Liverpool (England) for a transatlantic voyag ...

, serving as a presidential elector

The United States Electoral College is the group of presidential electors required by the Constitution to form every four years for the sole purpose of appointing the president and vice president. Each state and the District of Columbia appo ...

in 1852 and 1856.

U.S. Representative

In 1857, Stevenson was elected to the first of two consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. For the duration of his tenure in that body, he served on the Committee on Elections. He favored admittingKansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

to the Union under the Lecompton Constitution

The Lecompton Constitution (1859) was the second of four proposed constitutions for the state of Kansas. Named for the city of Lecompton where it was drafted, it was strongly pro-slavery. It never went into effect.

History Purpose

The Lecompton Co ...

.

Like many Kentuckians, Stevenson was sympathetic to the southern states' position in the lead-up to the

Like many Kentuckians, Stevenson was sympathetic to the southern states' position in the lead-up to the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, but he opposed secession as a means of dealing with sectional tensions. In the 1860 presidential election, he supported his close friend, John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier. He represented Kentucky in both houses of Congress and became the 14th and youngest-ever vice president of the United States. Serving ...

. Desiring to avert the Civil War, he advocated acceptance of the several proposed compromises, including the Crittenden Compromise

The Crittenden Compromise was an unsuccessful proposal to permanently enshrine slavery in the United States Constitution, and thereby make it unconstitutional for future congresses to end slavery. It was introduced by United States Senator Joh ...

, authored by fellow Kentuckian John J. Crittenden

John Jordan Crittenden (September 10, 1787 July 26, 1863) was an American statesman and politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He represented the state in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and twice served as United ...

. He blamed the Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as " Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reco ...

' rigid adherence to their demands for the failure of all such proposed compromises, and on January 30, 1861, denounced them in a speech that the ''Dictionary of American Biography

The ''Dictionary of American Biography'' was published in New York City by Charles Scribner's Sons under the auspices of the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS).

History

The dictionary was first proposed to the Council in 1920 by h ...

'' called the most notable of his career in the House.

Stevenson was defeated for reelection in 1861. For the duration of the war, which lasted until April 1865, he stayed out of public life in order to avoid being arrested as many other Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

sympathizers were. After the war, he was a delegate to the National Union Party's convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, in 1865. He was a supporter of the Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

policies of President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

.

Governor of Kentucky

Ex-Confederates dominated the Kentucky Democratic convention that met in Frankfort on February 22, 1867. John L. Helm, father of the late Confederate general Benjamin Hardin Helm, was nominated for governor and Stevenson was nominated for

Ex-Confederates dominated the Kentucky Democratic convention that met in Frankfort on February 22, 1867. John L. Helm, father of the late Confederate general Benjamin Hardin Helm, was nominated for governor and Stevenson was nominated for lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

. The entire Democratic slate of candidates was elected, including Stevenson, who received 88,222 votes to R. Tarvin Baker's 32,505 and H. Taylor's 11,473. The only non-Confederate sympathizer to win election that year was George Madison Adams, congressman for the state's 8th district

8 (eight) is the natural number following 7 and preceding 9.

In mathematics

8 is:

* a composite number, its proper divisors being , , and . It is twice 4 or four times 2.

* a power of two, being 2 (two cubed), and is the first number of the ...

who, although a Democrat, was a former federal soldier. Helm took the oath of office on his sick bed at his home in Elizabethtown, Kentucky

Elizabethtown is a home rule-class city and the county seat of Hardin County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 28,531 at the 2010 census, and was estimated at 30,289 by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2019, making it the 11th-largest city ...

, on September 3, 1867. He died five days later, and Stevenson was sworn in as governor on September 13. Among his first acts as governor were the appointments of Frank Lane Wolford

Frank Lane Wolford (September 2, 1817 – August 2, 1895) was a United States House of Representatives, U.S. Representative from Kentucky.

Wolford was born near Columbia, Kentucky. He attended the common schools, studied law and was Admis ...

, a former Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

soldier, as adjutant general

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

and Fayette Hewitt, a former Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

soldier, as state quartermaster general.

Because Helm died so soon after taking office, a special election for the remainder of his term was set for August 1868. Democrats held a convention in Frankfort on February 22, 1868 and nominated Stevenson to finish out Helm's term. R. Tarvin Baker, formerly Stevenson's opponent in the election for lieutenant governor, was the choice of the Republicans

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

. The Republicans faced many disadvantages, including the national party's persecution of President Johnson and a lack of local organization in many Kentucky counties. Despite Stevenson's shortcomings as a public speaker, he was elected in a landslide—115,560 to 26,605. At the time, it was the largest majority obtained by any candidate in a Kentucky election.

Civil rights

Post-war Kentucky Democrats had split into two factions—the more conservativeBourbon Democrats

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, especially those who suppo ...

and the more progressive New Departure Democrats. Stevenson governed moderately, giving concessions to both sides. He urged the immediate restoration of all rights to ex-Confederates and denounced Congress for failing to seat a portion of the Kentucky delegation because they had sided with the Confederacy. A champion of states' rights, he resisted federal measures he saw as violating the sovereignty of the states and vehemently denounced the proposed Fifteenth Amendment. Following Stevenson's lead, the General Assembly refused to pass either the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendment, but after their passage by a constitutional majority of the states Stevenson generally insisted that blacks' newly granted rights not be infringed upon. He was silent, however, when state legislators and officials from various cities used lengthy residency restrictions and redrawn district and municipal boundaries to exclude black voters from specific elections. His 1867 plea for legislators to call a constitutional convention to revise the state's pro-slavery constitution to better conform to post-war reality was completely ignored.

Stevenson opposed almost every effort to expand blacks' rights beyond the minimums assured by federal amendments and legislation. The Civil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (, enacted April 9, 1866, reenacted 1870) was the first United States federal law to define citizenship and affirm that all citizens are equally protected by the law. It was mainly intended, in the wake of the Amer ...

guaranteed that blacks could testify against whites in federal courts, but he opposed New Departure Democrats when they insisted that Kentucky amend its laws to also allow black testimony against whites in state courts, and the measure failed in the 1867 legislative session. Later that year, the Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky.

The ...

declared the Civil Rights Act unconstitutional, but a federal court soon overturned that decision. Stevenson backed Bourbon Democrats' appeal of that decision to the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

. By 1871, however, he had changed his mind and supported blacks' right to testify. Despite Stevenson's support, the measure failed in the General Assembly again in 1871, but it passed the following year, after Stevenson had left office.

In the 1870 election, the first state in which blacks were allowed to vote, Stevenson warned that violence against them would not be tolerated. Although he relied on local authorities to suppress any incidents, he offered rewards for the apprehension of perpetrators of election-related violence. Stevenson also recommended that the carrying of concealed weapons be outlawed. The General Assembly passed the requested legislation on March 22, 1871. The law imposed small fines for the first offense, but the amount rapidly increased for subsequent infractions in order to deter repeat offenders.

State matters

In Stevenson's first message to the legislature, he called on legislators to finally decide whether the state capital would remain at Frankfort or be moved to Lexington orLouisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

, as some had wanted. His address made it clear that he favored keeping the capital at Frankfort, but he noted that additional space was needed at the present capitol building because the existing building could not continue to house enough room both the state treasurer

In the state governments of the United States, 48 of the 50 states have the executive position of treasurer. New York abolished the position in 1926; duties were transferred to New York State Comptroller. Texas abolished the position of Texas ...

and auditor. He laid out a vision for an addition to the capitol that would make it more spacious and more grandiose. To pay for the expansion, the fiscally conservative Stevenson pressed the federal government to pay claims due Kentucky from Civil War expenses. By the end of his term, the state had collected over $1.5 million in claims. The legislature, however, disregarded his plan for expanding the capitol, instead opting to construct a separate executive office building next to the capitol.

Stevenson also advocated careful study of the state's finances to deal with increasing expenditures. He insisted that the state stop covering its short-term indebtedness using bonds. However, Stevenson was willing to tax to benefit segregation in schools, and helped create the state bureau of education in 1870. Because most blacks possessed little property of significant value, the new tax yielded little revenue to support their educational institutions. State legislators rejected his 1870 proposal to create a state bureau of immigration and statistics to spur interest in and migration to the state. He did persuade the legislators to make some improvements in the state's penal and eleemosynary institutions, including establishing a House of Reform for juvenile offenders.

Mob violence, much of it perpetrated by vigilantes calling themselves "Regulators" who felt that local authorities had failed in their duties to protect the people, was an ongoing problem during Stevenson's administration. In September 1867, Stevenson urged all Kentuckians to defer to local authorities and ordered that all vigilante groups be disbanded. On October 1, however, a group calling themselves "Rowzee's band" began perpetrating anti-Regulator violence in Marion County. He dispatched Adjutant General Wolford to Marion County, authorizing him to use the state militia to quell the violence if necessary. Wolford called out three companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared go ...

of militia who suppressed "Rowzee's band" and sent another to put down a similar movement in Boyle County. Later in October, Stevenson dispatched the state militia to Mercer County, and militiamen were dispatched to Boyle, Garrard, and Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincoln ...

counties in 1869. The governor declared that he would never hesitate to send troops "whenever it becomes necessary for the arrest and bringing to justice of all those who combine together, no matter under what pretense, to trample the law under their feet by acts of personal violence."

U.S. Senator

Beginning in late 1869, Stevenson attacked Kentucky SenatorThomas C. McCreery

Thomas Clay McCreery (December 12, 1816July 10, 1890) was a Democratic Party (United States), Democratic United States Senate, U.S. Senator from Kentucky.

Born at Yelvington, Kentucky, McCreery graduated from Centre College, in Danville, Kentu ...

and Representative Thomas Laurens Jones

Thomas Laurens Jones (January 22, 1819 – June 20, 1887) was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky.

Born in White Oak, North Carolina, Jones attended private schools. He graduated from Princeton College and from the law department of Harvard Univ ...

for allegedly supporting President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

's nomination of former Union General Stephen G. Burbridge to a federal position in the revenue service. Although born in northern Kentucky, Burbridge had commanded colored troops during the Civil War, and had also been specifically ordered to suppress Confederate guerillas in his home state. Kentucky's General Assembly had sought to bring him to trial for war crimes in 1863 and 1864. Historian E. Merton Coulter

Ellis Merton Coulter (1890–1981) was an American historian of the South, author, and a founding member of the Southern Historical Association. For four decades, he was a professor at the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia, where he was ...

wrote of Burbridge: " he people of Kentuckyrelentlessly pursued him, the most bitterly hated of all Kentuckians, and so untiring were their efforts, that it finally came to the point where he had not a friend left in the state who would raise his voice to defend him." Stevenson's attacks on McCreery and Jones were likely designed to discredit them both in advance of the expiration of McCreery's Senate term in 1870. McCreery vigorously denied Stevenson's charges and eventually challenged him to a duel. Stevenson declined the challenge, citing his Christian beliefs. The General Assembly met to choose McCreery's successor in December 1869 and, on the fifth ballot, chose Stevenson over McCreery for the six-year Senate term. Stevenson resigned the governorship on February 13, 1871, in advance of the March congressional session.

In the Senate, Stevenson was a conservative stalwart, steadfastly opposing spending on internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

and maintaining a strict constructionist view of the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

. He urged his fellow senators to oppose the Civil Rights Act of 1871

The Enforcement Act of 1871 (), also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, Third Enforcement Act, Third Ku Klux Klan Act, Civil Rights Act of 1871, or Force Act of 1871, is an Act of the United States Congress which empowered the President to suspend t ...

, claiming that its provision that the president could suspend the right of ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'' in cases where he believed violence was imminent amounted to giving the chief executive the powers of a dictator. He also opposed the appropriation of federal money to fund the Centennial Exposition

The Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, the first official World's Fair to be held in the United States, was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from May 10 to November 10, 1876, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the signing of the ...

in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, because he did not believe Congress was given the authority to make such an allocation under the Constitution.

At the 1872 Democratic National Convention

The 1872 Democratic National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held at Ford's Grand Opera House on East Fayette Street, between North Howard and North Eutaw Streets, in Baltimore, Maryland on July 9 and 10, 1872. It resulted in ...

, Stevenson received the votes of Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

's six delegates for the Democratic vice-presidential nomination, although Benjamin Gratz Brown

Benjamin Gratz Brown (May 28, 1826December 13, 1885) was an American politician. He was a U.S. Senator, the 20th Governor of Missouri, and the Liberal Republican and Democratic Party vice presidential candidate in the presidential election of ...

was ultimately nominated. In February 1873, Vice-President Schuyler Colfax

Schuyler Colfax Jr. (; March 23, 1823 – January 13, 1885) was an American journalist, businessman, and politician who served as the 17th vice president of the United States from 1869 to 1873, and prior to that as the 25th speaker of the House ...

named Stevenson as one of five members of the Morrill Commission to investigate New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

Senator James W. Patterson

James Willis Patterson (July 2, 1823May 4, 1893) was an American politician and a United States representative and Senator from New Hampshire.

Early life, education and family

Born in Henniker, Merrimack County, New Hampshire, he was the son ...

's involvement in the Crédit Mobilier of America scandal.Hinds and Cannon, p. 837 Stevenson and fellow Senator John P. Stockton

John Potter Stockton (August 2, 1826January 22, 1900) was a New Jersey politician who served in the United States Senate as a Democratic Party (United States), Democrat. He was New Jersey Attorney General for twenty years (1877 to 1897), and ser ...

of New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

both asked to be removed from the commission, but the Senate refused to grant their request. On February 27, 1873, the commission recommended Patterson's expulsion from the Senate, but the chamber adjourned on March 4 without acting on the recommendation. Patterson's term ended with the end of the session, and he was not re-elected, rendering moot further consideration of the matter.

From December 1873 until the expiration of his term in 1877, Stevenson was generally recognized as the chairman (later known as the floor leader

In politics, floor leaders, also known as a caucus leader, are leaders of their respective political party in a body of a legislature.

Philippines

In the Philippines each body of the bicameral Congress has a majority floor leader and a minor ...

) of the minority Democratic caucus

A congressional caucus is a group of members of the United States Congress that meet to pursue common legislative objectives. Formally, caucuses are formed as congressional member organizations (CMOs) through the United States House of Represent ...

in the Senate; he was the first person to have acted in the capacity. During the Forty-fourth Congress

The 44th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1875, ...

, he chaired the Committee on Revolutionary Claims

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them more ...

. He did not seek reelection at the end of his term. In the disputed 1876 presidential election

The 1876 United States presidential election was the 23rd quadrennial United States presidential election, presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 7, 1876, in which Republican Party (United States), Republican nominee Rutherford B. Haye ...

, he was one of the visiting statesmen who went to New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, and concluded that the election had been fairly conducted in that state.

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Later life and death

After his service in the Senate, Stevenson returned to his law practice in Covington. In addition, he accepted a position teaching criminal law and contracts at theUniversity of Cincinnati College of Law

The University of Cincinnati College of Law was founded in 1833 as the Cincinnati Law School. It is the fourth oldest continuously running law school in the United States — after Harvard, the University of Virginia, and Yale — and the first in ...

. He remained interested in politics and was chosen chairman of the 1879 Democratic state convention in Louisville and president of the 1880 Democratic National Convention

The 1880 Democratic National Convention was held June 22 to 24, 1880, at the Music Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio, and nominated Winfield S. Hancock of Pennsylvania for president and William H. English of Indiana for vice president in the United Stat ...

in Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

.

In 1883, the American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of acad ...

began exploring the concept of dual federalism

Dual federalism, also known as layer-cake federalism or divided sovereignty, is a political arrangement in which power is divided between the federal and state governments in clearly defined terms, with state governments exercising those powers ...

. Because of his personal acquaintance with James Madison, whom he characterized as a proponent of dual federalism, Stevenson delivered an address on the subject at the Association's annual meeting. Stevenson maintained that Madison believed strongly in the rights of the sovereign states and regarded a Supreme Court appeal as "a remedy for trespass on the reserved rights of the states by unconstitutional acts of Congress." Stevenson was elected its president that year's and his address published. Association member Richard Vaux characterized Stevenson's presidential report reviewing state and federal legislation in 1885 as "most interesting and valuable to the profession".

Among the men who studied law under Stevenson in his later years were future U.S. Treasury Secretary John G. Carlisle and future Kentucky Governor William Goebel

William Justus Goebel (January 4, 1856 – February 3, 1900) was an American Democratic politician who served as the 34th governor of Kentucky for four days in 1900, having been sworn in on his deathbed a day after being shot by an assassin. ...

. Goebel eventually became Stevenson's law partner and the executor of his will.

In early August 1886, Stevenson traveled to Sewanee, Tennessee

Sewanee () is a census-designated place (CDP) in Franklin County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 2,535 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Tullahoma, Tennessee Micropolitan Statistical Area.

Sewanee is best known as the home of ...

, to attend the commencement ceremonies of Sewanee University. While there, he fell ill and was rushed back to his home in Covington, where he died on August 10, 1886. He was buried in Spring Grove Cemetery

Spring Grove Cemetery and Arboretum () is a nonprofit rural cemetery and arboretum located at 4521 Spring Grove Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio. It is the third largest cemetery in the United States, after the Calverton National Cemetery and Abraham L ...

in Cincinnati.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Text of Stevenson's protest to Congress for failing to seat the entire Kentucky delegation

(pages 2162 to 2171) , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Stevenson, John W. 1812 births 1886 deaths 19th-century American Episcopalians 19th-century American politicians American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law Burials at Spring Grove Cemetery Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Kentucky Democratic Party governors of Kentucky Democratic Party United States senators from Kentucky Kentucky lawyers Lieutenant Governors of Kentucky Democratic Party members of the Kentucky House of Representatives Mississippi lawyers Politicians from Covington, Kentucky Politicians from Richmond, Virginia Presidents of the American Bar Association 1852 United States presidential electors 1856 United States presidential electors University of Virginia alumni 19th-century American lawyers