John Tyndall (far-right Activist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Hutchyns Tyndall (14 July 193419 July 2005) was a British

Tyndall completed his

Tyndall completed his

Tyndall had "deeply entrenched" biologically racist views, akin to those of earlier fascists like Hitler and Leese. He believed that there was a biologically distinct white-skinned "British race" which was one branch of a wider

Tyndall had "deeply entrenched" biologically racist views, akin to those of earlier fascists like Hitler and Leese. He believed that there was a biologically distinct white-skinned "British race" which was one branch of a wider

Recent BNP arrests

BBC report 14 December 2004

''

"Obituary of John Tyndall"

19 July 2005 * ''BNP News'' 19 July 2005 {{DEFAULTSORT:Tyndall, John 1934 births 2005 deaths 20th-century English criminals Antisemitism in England British National Party politicians British people convicted of hate crimes English agnostics English conspiracy theorists English far-right politicians English neo-Nazis British Holocaust deniers English politicians convicted of crimes British fascists British white supremacists Leaders of political parties in the United Kingdom Leaders of the National Front (UK) People educated at Beckenham and Penge County Grammar School Politicians from Exeter

fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

political activist. A leading member of various small neo-Nazi

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazism, Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and Supremacism#Racial, racial supremacy (ofte ...

groups during the late 1950s and 1960s, he was chairman of the National Front (NF) from 1972 to 1974 and again from 1975 to 1980, and then chairman of the British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

(BNP) from 1982 to 1999. He unsuccessfully stood for election to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

and European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and informally as the Council of Ministers), it adopts ...

on several occasions.

Born in Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

and educated in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, Tyndall undertook national service

National service is the system of voluntary government service, usually military service. Conscription is mandatory national service. The term ''national service'' comes from the United Kingdom's National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939.

The l ...

prior to embracing the extreme-right. In the mid-1950s, he joined the League of Empire Loyalists

The League of Empire Loyalists (LEL) was a British pressure group (also called a "ginger group" in Britain and the Commonwealth of Nations), established in 1954. Its ostensible purpose was to stop the dissolution of the British Empire. The League ...

(LEL) and came under the influence of its leader, Arthur Chesterton. Finding the LEL too moderate, in 1957 he and John Bean

John Bean may refer to:

* John Bean (cricketer) (1913–2005), English cricketer and British Army officer

* John Bean (politician) (1927–2021), long-standing participant in the British far right

* John Bean (explorer) ( 1751–1757), Canadian e ...

founded the National Labour Party (NLP), an explicitly "National Socialist

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

" (Nazi) group. In 1960, the NLP merged with Colin Jordan

John Colin Campbell Jordan (19 June 1923 – 9 April 2009) was a leading figure in post-war neo-Nazism in Great Britain. In the far-right circles of the 1960s, Jordan represented the most explicitly "Nazi" inclination in his open use of the st ...

's White Defence League

The White Defence League (WDL) was a British neo-Nazi political party. Using the provocative marching techniques popularised by Oswald Mosley, its members included John Tyndall.

Formation

The WDL had its roots in Colin Jordan's decision to spl ...

to found the first British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

(BNP). Within the BNP, Tyndall and Jordan established a paramilitary wing called Spearhead, which angered Bean and other party members. They expelled Tyndall and Jordan, who went on to establish the National Socialist Movement National Socialist Movement may refer to:

* Nazi Party, a political movement in Germany

* National Socialist Movement (UK, 1962), a British neo-Nazi group

* National Socialist Movement (United Kingdom), a British neo-Nazi group active during the lat ...

and then the international World Union of National Socialists

The World Union of National Socialists (WUNS) is an organisation founded in 1962 as an umbrella group for neo-Nazi organisations across the globe.

History Formation

The movement came about when the leader of the American Nazi Party, Geor ...

. In 1962, they were convicted and briefly imprisoned for their paramilitary activities. After a split with Jordan, Tyndall formed his Greater Britain Movement

The Greater Britain Movement was a British far right political group formed by John Tyndall in 1964 after he split from Colin Jordan's National Socialist Movement. The name of the group was derived from ''The Greater Britain'', a 1932 book by Os ...

(GBM) in 1964. Although never changing his basic beliefs, by the mid-1960s, Tyndall was replacing his overt references to Nazism with appeals to British nationalism

British nationalism asserts that the British are a nation and promotes the cultural unity of Britons,Guntram H. Herb, David H. Kaplan. Nations and Nationalism: A Global Historical Overview: A Global Historical Overview. Santa Barbara, Californi ...

.

In 1967, Tyndall joined Chesterton's newly founded National Front (NF) and became its leader in 1972, overseeing growing membership and electoral growth. His leadership was threatened by various factions within the party which eventually led to him losing his position as leader in 1974. He resumed this position in 1975, although the latter part of the 1970s saw the party's prospects decline. Following an argument with long-term comrade Martin Webster

Martin Guy Alan Webster (born 14 May 1943) is a British neo-nazi, a former leading figure on the far-right in the United Kingdom. An early member of the National Labour Party, he was John Tyndall's closest ally, and followed him in joining ...

, Tyndall resigned from the party in 1980 and formed his short-lived New National Front (NNF). In 1982, he merged the NNF into his own newly formed British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

(BNP). Under Tyndall, the BNP established itself as the UK's most prominent extreme-right group during the 1980s, although electoral success eluded it. Tyndall's refusal to moderate the BNP's policies or image caused anger among a growing array of "modernisers" in the party, who ousted him in favour of Nick Griffin

Nicholas John Griffin (born 1 March 1959) is a British politician and white supremacist who represented North West England as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) from 2009 to 2014. He served as chairman and then president of the far-righ ...

in 1999. In 2005, Tyndall was charged with incitement to racial hatred

Incitement to ethnic or racial hatred is a crime under the laws of several countries.

Australia

In Australia, the Racial Hatred Act 1995 amends the Racial Discrimination Act 1975, inserting Part IIA – Offensive Behaviour Because of Race, Colour ...

for comments made at a BNP meeting. He died two days before his trial was due to take place.

Tyndall promoted a racial nationalist belief in a distinct white "British race", arguing that this race was threatened by a Jewish conspiracy to encourage non-white migration into Britain. He called for the establishment of an authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

state which would deport all non-whites from the country, engage in a eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

project, and re-establish the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

through the military conquest of parts of Africa. He never gained any mainstream political respectability in the United Kingdom although he proved popular among sectors of the British far-right.

Early life

1934–1958: Youth

John Tyndall was born in Stork Nest, Topsham Road inExeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

, Devon, on 14 July 1934, the son of Nellie Tyndall, ''née'' Parker and George Francis Tyndall. Through the Tyndall family line, he was related to the early English translator of the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

, William Tyndale

William Tyndale (; sometimes spelled ''Tynsdale'', ''Tindall'', ''Tindill'', ''Tyndall''; – ) was an English biblical scholar and linguist who became a leading figure in the Protestant Reformation in the years leading up to his executi ...

and the physicist John Tyndall

John Tyndall FRS (; 2 August 1820 – 4 December 1893) was a prominent 19th-century Irish physicist. His scientific fame arose in the 1850s from his study of diamagnetism. Later he made discoveries in the realms of infrared radiation and the p ...

. His paternal family were British Unionists living in County Waterford

County Waterford ( ga, Contae Phort Láirge) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and is part of the South-East Region, Ireland, South-East Region. It is named ...

, Ireland, who had a long line of service in the Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

. His grandfather had been a district inspector in the Constabulary and he had also fought against the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

during the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

. His father had moved to England, working as a Metropolitan Police

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

officer, and then he worked as a warden at St George's House, a YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

hostel in Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

. Tyndall later stated that despite the fact that his father had been raised in a British Unionist family, the latter had adopted internationalist

Internationalist may refer to:

* Internationalism (politics), a movement to increase cooperation across national borders

* Liberal internationalism, a doctrine in international relations

* Internationalist/Defencist Schism, socialists opposed to ...

views. He claimed that his mother exhibited "a kind of basic British patriotism" and he also claimed that it was she who shaped his early political views. His upbringing was emotionally stable and materially secure. Tyndall studied at the Beckenham and Penge Grammar School in west Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, where he attained three O-levels

The O-Level (Ordinary Level) is a subject-based qualification conferred as part of the General Certificate of Education. It was introduced in place of the School Certificate in 1951 as part of an educational reform alongside the more in-depth ...

, a "moderate" result. At the school, his achievements had been sporting rather than academic, because he enjoyed playing cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

and association football and he also developed a passion for fitness.

Tyndall completed his

Tyndall completed his national service

National service is the system of voluntary government service, usually military service. Conscription is mandatory national service. The term ''national service'' comes from the United Kingdom's National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939.

The l ...

in West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

from 1952 to 1954. A member of the Royal Horse Artillery

The Royal Horse Artillery (RHA) was formed in 1793 as a distinct arm of the Royal Regiment of Artillery (commonly termed Royal Artillery) to provide horse artillery support to the cavalry units of the British Army. (Although the cavalry link ...

, he achieved the rank of lance-bombardier. On completion, he returned to Britain and turned his attention to political issues. Initially interested in socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

, he attended a world youth festival which was held in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

in 1957. Nevertheless, he began to believe that left-wing politics

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political%20ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically in ...

was being infused with "anti-British attitudes", moving swiftly to the political right

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, auth ...

. He was devoted to the preservation of the British Empire and he was hostile to what he believed was the growing permissiveness of British society, stating that "the smell everywhere was one of decadence". During that decade he read ''Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germ ...

'', the autobiography and political manifesto of the Nazi leader Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, growing sympathetic to Hitler's political beliefs

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies ...

and Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

. In particular, Tyndall approved of "the descriptions of the workings of certain Jewish forces in Germany, which seemed uncannily similar to what I had observed of the same kinds of forces in Britain." He concluded that Britain's decision to go to war against Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

was ultimately the result of a conspiracy which was primarily headed by Jews, a conspiracy which he thought had also masterminded non-white immigration to Britain after the war.

Around 1957–58, Tyndall decided to commit himself to his political cause full-time, which he was able to do because his job as a salesman allowed him to keep flexible working hours. He decided against joining the Union Movement

The Union Movement (UM) was a far-right political party founded in the United Kingdom by Oswald Mosley. Before the Second World War, Mosley's British Union of Fascists (BUF) had wanted to concentrate trade within the British Empire, but the Uni ...

which was led by the prominent British fascist Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to fascism. He was a member ...

, disagreeing with its promotion of the political union of Britain with continental Europe. Instead, he was attracted to the League of Empire Loyalists

The League of Empire Loyalists (LEL) was a British pressure group (also called a "ginger group" in Britain and the Commonwealth of Nations), established in 1954. Its ostensible purpose was to stop the dissolution of the British Empire. The League ...

(LEL)a right-wing group founded by Arthur Chestertonafter seeing coverage of one of their demonstrations on television. He visited their basement office in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

, where he was given some of their literature. He enjoyed Chesterton's writings and concurred with his conspiracy theory

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

that Jewish people had been plotting to bring down the British Empire. Tyndall began associating with other young men who had joined the LEL. At a February 1957 by-election in Lewisham North, Tyndall aided the LEL campaign, during which he met another party member, John Bean

John Bean may refer to:

* John Bean (cricketer) (1913–2005), English cricketer and British Army officer

* John Bean (politician) (1927–2021), long-standing participant in the British far right

* John Bean (explorer) ( 1751–1757), Canadian e ...

, an industrial chemist. Both Tyndall and Bean were frustrated by the LEL's attempts to exert pressure on the mainstream Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

. They wanted to be involved in a more radical party, one that would combine "nationalism" with "popular socialism" and which would reach out to the white working class through appeals against immigration from the Caribbean.

1958–1962: National Labour Party and the first British National Party

In April 1958, Tyndall and Bean founded their own extreme-right group, the National Labour Party (NLP). The group was based atThornton Heath

Thornton Heath is a district of Greater London, England, within the London Borough of Croydon. It is around north of the town of Croydon, and south of Charing Cross. Prior to the creation of Greater London in 1965, Thornton Heath was in the Co ...

, Croydon

Croydon is a large town in south London, England, south of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Croydon, a local government district of Greater London. It is one of the largest commercial districts in Greater London, with an extensi ...

and attracted its early membership from former LEL members living in south and east London. According to the historian Richard Thurlow, the NLP promoted an "English" variant of Nazism and was more pronounced in its "explicit racism" than the LEL had been, focusing less on bemoaning the decline of the British Empire and more on criticising the arrival of non-white immigrants from former British colonies.

The NLP began co-operating with another extreme-right group, the White Defence League

The White Defence League (WDL) was a British neo-Nazi political party. Using the provocative marching techniques popularised by Oswald Mosley, its members included John Tyndall.

Formation

The WDL had its roots in Colin Jordan's decision to spl ...

, which had been established by Colin Jordan

John Colin Campbell Jordan (19 June 1923 – 9 April 2009) was a leading figure in post-war neo-Nazism in Great Britain. In the far-right circles of the 1960s, Jordan represented the most explicitly "Nazi" inclination in his open use of the st ...

, a secondary school teacher. Together the two groups embarked on a project of stirring up racial tensions among white Britons and black Caribbean immigrants in Notting Hill

Notting Hill is a district of West London, England, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Notting Hill is known for being a cosmopolitan and multicultural neighbourhood, hosting the annual Notting Hill Carnival and Portobello Road M ...

. Tyndall briefly left the NLP and in his absence Bean and Jordan merged their respective groups into the British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

(BNP) in 1960. The BNP were racial nationalists, calling for the preservation of a "Nordic race

The Nordic race was a racial concept which originated in 19th century anthropology. It was considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race, claiming th ...

"—of which the "British race" was considered a branch—by removing both immigrants and Jewish influences from Britain. Tyndall soon joined this new BNP, and became a close confidante of Jordan, who helped Tyndall to further embrace neo-Nazism

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazism, Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and Supremacism#Racial, racial supremacy (ofte ...

. Tyndall also developed a friendship with Martin Webster

Martin Guy Alan Webster (born 14 May 1943) is a British neo-nazi, a former leading figure on the far-right in the United Kingdom. An early member of the National Labour Party, he was John Tyndall's closest ally, and followed him in joining ...

, who became a long-term comrade after watching Tyndall speak at a Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson commemo ...

rally in 1962.

In April 1961, Tyndall self-published his pamphlet, ''The Authoritarian State: Its Meaning and Function'', which helped to cement his reputation within the British far-right. In the pamphlet, he attacked democratic systems of government as part of a conspiracy orchestrated by Jews, quoting from ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' () or ''The Protocols of the Meetings of the Learned Elders of Zion'' is a fabricated antisemitic text purporting to describe a Jewish plan for global domination. The hoax was plagiarized from several ...

''. It called for the replacement of the United Kingdom's liberal democratic

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into di ...

system with an authoritarian one in which a "Leader" is given absolute power.

Within the BNP, Tyndall established an elite group known as Spearhead, members of which wore military-style uniforms inspired by those of the Nazis and underwent paramilitary and ideological training. Tyndall had a great liking for wearing jackboot

A jackboot is a military boot such as the cavalry jackboot or the hobnailed jackboot. The hobnailed jackboot has a different design and function from the first type. It is a combat boot that is designed for marching. It rises to mid-calf or highe ...

s - Jordan related that on the way to a far-right meeting in Germany, Tyndall made his entourage look for a shoe shop so that he could purchase a pair of genuine German jackboots. It is likely that there were no more than 60 members of Spearhead. The group campaigned on behalf of imprisoned Nazi war criminals Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer to Adolf Hitler in 1933, Hess held that position unt ...

and Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

''

Although the British authorities had prohibited the American neo-Nazi

Although the British authorities had prohibited the American neo-Nazi

In the mid-1960s, there were five extreme-right groups operating in Britain and Tyndall believed that they could achieve more if they united. To that end, ''Spearhead'' abandoned its open affiliation with neo-Nazism in 1966. That year, Tyndall issued a pamphlet titled ''Six Principles of British Nationalism'' which made no mention of neo-Nazism or Jewish conspiracies. It also dropped the insistence on armed takeovers present in his earlier thought, acknowledging the possibility that extreme-right nationalists could gain power through the British electoral process. Chesterton read the pamphlet and was impressed, entering into talks with Tyndall's GBM about a potential merger of their respective organisations. Independently, Chesterton had also been discussing the issue of a unification with Bean's BNP. This proved successful, as the LEL and BNP merged to form the National Front (NF) in 1967. According to Thurlow, the formation of the NF was "the most significant event on the radical right and fascist fringe of British politics" since the internment of the country's fascists during the

In the mid-1960s, there were five extreme-right groups operating in Britain and Tyndall believed that they could achieve more if they united. To that end, ''Spearhead'' abandoned its open affiliation with neo-Nazism in 1966. That year, Tyndall issued a pamphlet titled ''Six Principles of British Nationalism'' which made no mention of neo-Nazism or Jewish conspiracies. It also dropped the insistence on armed takeovers present in his earlier thought, acknowledging the possibility that extreme-right nationalists could gain power through the British electoral process. Chesterton read the pamphlet and was impressed, entering into talks with Tyndall's GBM about a potential merger of their respective organisations. Independently, Chesterton had also been discussing the issue of a unification with Bean's BNP. This proved successful, as the LEL and BNP merged to form the National Front (NF) in 1967. According to Thurlow, the formation of the NF was "the most significant event on the radical right and fascist fringe of British politics" since the internment of the country's fascists during the

Tyndall stood as the BNP candidate in the 1994 Dagenham by-election, in which he gained 9% of the vote and had his

Tyndall stood as the BNP candidate in the 1994 Dagenham by-election, in which he gained 9% of the vote and had his

documentary, ''The Secret Agent''. On 12 December 2004, these comments resulted in Tyndall being arrested on suspicion of incitement to racial hatred. That month, Tyndall was again expelled from the BNP, this time permanently. The police then charged him, although he was granted unconditional bail in April 2005. Tyndall died of heart failure at his flat—52 Westbourne Villas in Hove—on 19 July 2005. He had been due to stand trial at ''

anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were ...

activist Gerry Gable, Spearhead represented the first "terrorist group" founded by neo-Nazis in Britain. Both Bean and another senior BNP member, Andrew Fountaine, were concerned about the overt neo-Nazism embraced by Tyndall and Jordan, instead thinking that the BNP should articulate a more British-oriented form of racial nationalism. In 1962, Bean held a meeting at which Tyndall and Jordan were expelled from the party.

1962–1967: National Socialist Movement and Greater Britain Movement

Tyndall and Jordan then regrouped around twenty members of Spearhead and formed theNational Socialist Movement National Socialist Movement may refer to:

* Nazi Party, a political movement in Germany

* National Socialist Movement (UK, 1962), a British neo-Nazi group

* National Socialist Movement (United Kingdom), a British neo-Nazi group active during the lat ...

(NSM) on 20 April 1962, a date symbolically chosen as Hitler's birthday. They celebrated the event with a cake decorated with a Nazi swastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍) is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly in various Eurasian, as well as some African and American cultures, now also widely recognized for its appropriation by the Nazi Party and by neo-Nazis. It ...

. According to the historian Richard Thurlow, the NSM was "the most blatant Nazi" group active in Britain during the mid-20th century. The NSM gained few members; an estimate in August 1962 suggested that it had only thirty to fifty. The NSM gained the attention of the media as well as Special Branch

Special Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security and Intelligence (information gathering), intelligence in Policing in the United Kingdom, British, Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, ...

. In July 1962, Tyndall was arrested for breaching the peace at a Trafalgar Square rally in which he had been attacked by Jewish military veterans and other anti-fascists after calling the Jewish community a "poisonous maggot feeding on a body in an advanced state of decay". His comments resulted in him being convicted of inciting racial hatred and he was sentenced to six weeks imprisonment, reduced to a fine on appeal. The police then raided the group's London headquarters, after which its leading members were brought to trial at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

, where they were found guilty of establishing a paramilitary group in contravention of Section Two of the Public Order Act 1936

The Public Order Act 1936 (1 Edw. 8 & 1 Geo. 6 c. 6) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed to control extremist political movements in the 1930s such as the British Union of Fascists (BUF).

Largely the work of Home Office ci ...

. Tyndall received a six-month prison sentence, while Jordan received nine months.

Although the British authorities had prohibited the American neo-Nazi

Although the British authorities had prohibited the American neo-Nazi George Lincoln Rockwell

George Lincoln Rockwell (March 9, 1918 – August 25, 1967) was an American far-right political activist and founder of the American Nazi Party. He later became a major figure in the neo-Nazi movement in the United States, and his beliefs, st ...

from entering the UK, the NSM managed to smuggle him in via Ireland to attend a summer camp in August 1962. There, the NSM took part in the formation of the World Union of National Socialists

The World Union of National Socialists (WUNS) is an organisation founded in 1962 as an umbrella group for neo-Nazi organisations across the globe.

History Formation

The movement came about when the leader of the American Nazi Party, Geor ...

(WUNS), at which Jordan was elected 'world führer' and Rockwell as his heir. Among those in attendance were the neo-Nazi Savitri Devi

Savitri Devi Mukherji (born Maximiani Julia Portas, ; 30 September 1905 – 22 October 1982) was a French-born Greek fascist, Nazi sympathizer, and spy who served the Axis powers by committing acts of espionage against the Allied forces in I ...

and the former SS officer Fred Borth.

Jordan had been courting the French socialite Françoise Dior

Marie Françoise Suzanne Dior (7 April 1932 – 20 January 1993) was a French socialite and neo-Nazi underground financier. She was the niece of French fashion designer Christian Dior and Resistance fighter Catherine Dior, who publicly distance ...

, but while he had been imprisoned, she entered a relationship with Tyndall and they were engaged to be married. On Jordan's release, Dior left Tyndall and instead married Jordan in October 1963. This contributed to a growing personal feud between the two men, with Jordan accusing Tyndall and Webster of making obscene phone calls to Dior. Tyndall was also angry at what he perceived as Jordan's deviation from orthodox Nazi thought and by the fact that Jordan's relationship with Dior had been attracting negative sensationalist press attention for the NSM. In the spring of 1964 Tyndall and Webster tried to oust Jordan as the head of the NSM but failed. In later years Tyndall expressed the view that his involvement in the NSM had been a "profound mistake", arguing that then he "still had a lot to learn" and that "when one sees one's nation and people in danger there is less dishonour in acting and acting wrongly than in not acting at all."

Now based in Battersea

Battersea is a large district in south London, part of the London Borough of Wandsworth, England. It is centred southwest of Charing Cross and extends along the south bank of the River Thames. It includes the Battersea Park.

History

Batter ...

, Tyndall left Jordan and the NSM and formed his own rival, the Greater Britain Movement

The Greater Britain Movement was a British far right political group formed by John Tyndall in 1964 after he split from Colin Jordan's National Socialist Movement. The name of the group was derived from ''The Greater Britain'', a 1932 book by Os ...

(GBM). According to Tyndall, "the Greater Britain Movement will uphold and preach pure National Socialism". According to the political scientist Stan Taylor, the GBM reflected Tyndall's desire for "a specifically British variant of National Socialism". It called for the criminalisation of sexual relations and marriages between white Britons and non-whites and called for the sterilisation of those it deemed unfit to reproduce. The group established its base in a run-down building in Notting Hill, with swastikas being sprayed onto the exterior and an image of Hitler decorating the interior. Tyndall tried to convince the WUNS to accept his GBM as its British representative, but Rockwell—concerned not to encourage schismatic dissenters in his own American Nazi Party

The American Nazi Party (ANP) is an American far-right and neo-Nazi political party founded by George Lincoln Rockwell and headquartered in Arlington, Virginia. The organization was originally named the World Union of Free Enterprise National ...

—sided with Jordan and the NSM. Tyndall then established contact with Rockwell's main rival in the American neo-Nazi scene, the National States' Rights Party

The National States' Rights Party was a white supremacist political party that briefly played a minor role in the politics of the United States.

Foundation

Founded in 1958 in Knoxville, Tennessee, by Edward Reed Fields, a 26-year-old chiropractor ...

.

Tyndall formed a publishing company, Albion Press, and launched a new magazine which he titled '' Spearhead'' after his former paramilitary group. ''Spearhead'' initially labelled itself "an organ of National Socialist opinion in Britain" and described Nazi Germany as "one of the greatest social experiments of our century". According to the historian Alan Sykes

Sir Alan John Sykes, 1st Baronet (11 April 1868 – 21 May 1950) was an English businessman in the bleaching industry and Conservative politician in Cheshire.

Biography

Sykes was born at Cringle House Cheadle, the second son of Thomas Hardc ...

, this magazine became "increasingly influential" in the British far-right. The magazine advertised portraits of Hitler and swastika badges for sale. Much of the material that Tyndall wrote for the journal was less openly neo-Nazi and extreme than his previous writings, something which may have resulted from caution surrounding the Race Relations Act 1965

The Race Relations Act 1965 was the first legislation in the United Kingdom to address racial discrimination.

The Act outlawed discrimination on the "grounds of colour, race, or ethnic or national origins" in public places in Great Britain.

It ...

. The GBM engaged in several stunts to raise publicity; in 1964 for instance Webster assaulted the Kenyan leader Jomo Kenyatta

Jomo Kenyatta (22 August 1978) was a Kenyan anti-colonial activist and politician who governed Kenya as its Prime Minister from 1963 to 1964 and then as its first President from 1964 to his death in 1978. He was the country's first indigenous ...

outside his London hotel while Tyndall hurled insults at him through a loudspeaker. In 1965, the group staged a shooting incident at its Norwood headquarters, claiming that it had been an attack by anti-fascists. In another instance they distributed stickers emblazoned with a portrait of Hitler and the slogan "he was right". In 1966, several GBM members were arrested for carrying out arson attacks against synagogues.

Later career

1967–1980: National Front

In the mid-1960s, there were five extreme-right groups operating in Britain and Tyndall believed that they could achieve more if they united. To that end, ''Spearhead'' abandoned its open affiliation with neo-Nazism in 1966. That year, Tyndall issued a pamphlet titled ''Six Principles of British Nationalism'' which made no mention of neo-Nazism or Jewish conspiracies. It also dropped the insistence on armed takeovers present in his earlier thought, acknowledging the possibility that extreme-right nationalists could gain power through the British electoral process. Chesterton read the pamphlet and was impressed, entering into talks with Tyndall's GBM about a potential merger of their respective organisations. Independently, Chesterton had also been discussing the issue of a unification with Bean's BNP. This proved successful, as the LEL and BNP merged to form the National Front (NF) in 1967. According to Thurlow, the formation of the NF was "the most significant event on the radical right and fascist fringe of British politics" since the internment of the country's fascists during the

In the mid-1960s, there were five extreme-right groups operating in Britain and Tyndall believed that they could achieve more if they united. To that end, ''Spearhead'' abandoned its open affiliation with neo-Nazism in 1966. That year, Tyndall issued a pamphlet titled ''Six Principles of British Nationalism'' which made no mention of neo-Nazism or Jewish conspiracies. It also dropped the insistence on armed takeovers present in his earlier thought, acknowledging the possibility that extreme-right nationalists could gain power through the British electoral process. Chesterton read the pamphlet and was impressed, entering into talks with Tyndall's GBM about a potential merger of their respective organisations. Independently, Chesterton had also been discussing the issue of a unification with Bean's BNP. This proved successful, as the LEL and BNP merged to form the National Front (NF) in 1967. According to Thurlow, the formation of the NF was "the most significant event on the radical right and fascist fringe of British politics" since the internment of the country's fascists during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

The new NF initially excluded Tyndall and his GBM from joining, concerned that he might seek to mould it in a specifically neo-Nazi direction, although they soon agreed to allow both him and other GBM members to join on probation. On entering, the former GBM soon became the most influential faction within the NF, with many of its members rapidly rising to positions of influence. Tyndall became the party's vice chairman and remained loyal to Chesterton, who was the party's first chairman, for instance by supporting him when several members of the party directorate rebelled against his leadership in 1970. Although remaining Tyndall's private property, ''Spearhead'' became the ''de facto'' monthly magazine of the NF. Chesterton resigned as chairman in 1970 and was replaced by the Powellite

Powellite is a calcium molybdate mineral with formula CaMoO4. Powellite crystallizes with tetragonal - dipyramidal crystal structure as transparent adamantine blue, greenish brown, yellow to grey typically anhedral forms. It exhibits distinct cle ...

John O'Brien. In 1972, O'Brien and eight other members of the party's directorate resigned in protest at Tyndall's links to neo-Nazi groups in Germany. This allowed Tyndall to take control as party chairman in 1972.

According to Thurlow, under Tyndall the NF represented "an attempt to portray the essentials of Nazi ideology in more rational language and seemingly reasonable arguments", functioning as an attempt to "convert racial populists" angry about immigration "into fascists". Capitalising on anger surrounding the arrival of Ugandan Asian migrants in the country in 1972, Tyndall oversaw the NF during the period of its largest growth. Membership of the party doubled between October 1972 and June 1973, possibly reaching as high as 17,500.

Relations had apparently warmed between Tyndall and Jordan, for they met up after the latter was released from prison in 1968, and Tyndall again met with Jordan in Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its ...

in 1972 and invited him to join the NF. A poor showing in the February 1974 general election resulted in Tyndall being challenged by two groups within the party, the ' Strasserites' and the 'Populists

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

', the latter of whom were largely Powellite ex-members of the Conservative Party. The Populist challenge was successful and in October 1974 Tyndall was replaced as chairman by John Kingsley Read. Tyndall then used ''Spearhead'' as a vehicle to criticise rival factions with the NF. As a result, he was expelled from the party during a disciplinary tribunal in November 1975. Tyndall took the issue to the high court, who overturned the expulsion. The 'Populists' then left the party, splitting to form the National Party in January 1976, which for a short time proved more electorally successful than the NF. Back in the party and with his main rivals gone, Tyndall regained the position of chairman.

Encouraged by Webster and new confidante Richard Verrall

Richard Verrall (born 1948) is a British Holocaust denier and former deputy chairman of the British National Front (NF) who edited the magazine '' Spearhead'' from 1976 to 1980. Under the ''nom de plume'' (pen name) of Richard E. Harwood, Verr ...

, in the mid-1970s Tyndall returned to his openly hardline approach of promoting biological racist and antisemitic ideas. This did not help the NF's electoral prospects. In the 1979 general election, the NF mounted the largest challenge of any insurgent party since the Labour Party in 1918, with 303 candidates. Among them were Tyndall's wife, mother-in-law and father-in-law. Tyndall stood in Hackney South and Shoreditch

Hackney South and Shoreditch is a constituency represented in the House of Commons of the UK Parliament since 2005 by Meg Hillier of Labour Co-op.

History

The seat was created in February 1974 from the former seat of Shoreditch and Finsbury.

...

, securing 7.6%; this was the Front's best result that election, but was down from the 9.4% they had gained in that constituency in October 1974. In the election, the NF "flopped dismally", securing only 1.3% of the total vote, down from 3.1% in October 1974. This decline may have been due to the increased anti-fascist campaigning of the previous few years, or because the Conservative Party under Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

had adopted an increasingly tough stance on immigration which attracted many of the votes that had previously gone to the NF. NF membership had also declined and by 1979 had fallen to approximately 5,000. Tyndall nevertheless refused to dilute or moderate his party's policies, stating that to do so would be the "naïve chasing of moonbeams". In November 1979, Fountaine unsuccessfully tried to oust Tyndall as leader, subsequently establishing the National Front Constitutional Movement.

Tyndall had grown distant from Webster over their differences and in the late 1970s began blaming him for the party's problems. Webster had for instance disagreed with Tyndall's support for Chesterton's leadership, while Tyndall was upset with Webster's attempts to encourage more skinhead

A skinhead is a member of a subculture which originated among working class youths in London, England, in the 1960s and soon spread to other parts of the United Kingdom, with a second working class skinhead movement emerging worldwide in th ...

s and football hooligans

Football hooliganism, also known as soccer hooliganism, football rioting or soccer rioting, constitutes violence and other destructive behaviours perpetrated by spectators at association football events. Football hooliganism normally involves ...

to join the party. Tyndall in particular began criticizing the fact that Webster was a homosexual, emphasising allegations that Webster had been making sexual advances toward young men in the party. More widely, he complained about a "homosexual network" among leading NF members. In October 1979, he called a meeting of the NF directorate at which he urged them to call for Webster's resignation. At the meeting, Webster apologised for his conduct and the directorate stood by him against Tyndall. Angered, Tyndall then tried convincing the directorate to grant him greater powers in his position as chairman, but they refused. Tyndall resigned in January 1980, subsequently referring to the party as the "gay National Front".

In June 1980, Tyndall founded the New National Front

The British National Party (BNP) is a Far-right politics, far-right, Fascism, fascist list of political parties in the United Kingdom, political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walke ...

(NNF). The NNF claimed that a third of the NF's membership defected to join them. Tyndall stated that "I have one wish in this operation and one wish alone, to cleanse the National Front of the foul stench of perversion which has politically crippled it". As his choice of party name suggested, he remained hopeful that his breakaway group could eventually be re-merged back into the NF. There developed a great rivalry between the two groups, and as the NF's new leadership moved it away from the Tyndallite approach, Tyndall realised that he may never have the opportunity to regain his position within it.

1981–1989: Establishing the British National Party

In January 1981, Tyndall was contacted by far-right activist Ray Hill, who had become an informant for the anti-fascist magazine ''Searchlight

A searchlight (or spotlight) is an apparatus that combines an extremely bright source (traditionally a carbon arc lamp) with a mirrored parabolic reflector to project a powerful beam of light of approximately parallel rays in a particular direc ...

''. Hill suggested that Tyndall establish a new political party through which he could unite many smaller extreme-right groups. While Hill's real intention had been to cause a further schism among the British far-right and thus weaken it, Tyndall deemed his suggestion to be a good idea. Tyndall made suggestions of unity to a number of other small extreme-right groups and together they established a Committee for Nationalist Unity (CNU) in January 1982.

In March 1982 the CNU held a conference at Charing Cross Hotel

Charing Cross railway station (also known as London Charing Cross) is a central London railway terminus between the Strand and Hungerford Bridge in the City of Westminster. It is the terminus of the South Eastern Main Line to Dover via As ...

in central London and while the NF officially refused to send a delegation, several NF members did attend. The fifty extreme-rightists in attendance agreed that they would establish a new political party, to be known as the British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

(BNP). According to Tyndall, "The BNP is a racial nationalist party which believes in Britain for the British, that is to say racial separatism." Under Tyndall's leadership, in 1982 the BNP issued its first policy on immigration as "immigration into Britain by non-Europeans ... should be terminated forthwith and we should organise a massive programme of repatriation and resettlement overseas of those peoples of non-European origin already resident in this country."

Tyndall was to be the leader of this new party, with the majority of its members coming from the NNF, although others were defectors from the NF, British Movement, British Democratic Party

The British Democratic Party (BDP) was a short-lived far-right political party in the United Kingdom. A breakaway group from the National Front, the BDP was severely damaged after it became involved in a gun-running sting and was absorbed by the ...

and Nationalist Party. The party was formally launched at a press conference held in a Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

hotel on 7 April 1982. At the conference, Tyndall described the BNP as the "SDP of the far right", thereby referencing the recent growth of the centrist Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Fo ...

. The historian Nigel Copsey has noted that while the BNP under Tyndall could be described as "Neo-Nazi", it was not "crudely mimetic" of the original German Nazism. Its stated policy objectives were identical to those that the NF had had under Tyndall's leadership in the 1970s. But its constitution was very different. Whereas the NF had a directorate which helped to guide the direction of the party and could replace the leader, Tyndall's new BNP gave full executive powers to the chairman. Tyndall ran the BNP from his home, "Seacroft", in Hove

Hove is a seaside resort and one of the two main parts of the city of Brighton and Hove, along with Brighton in East Sussex, England. Originally a "small but ancient fishing village" surrounded by open farmland, it grew rapidly in the 19th cen ...

, East Sussex, and he rarely left the county.

In 1986 Tyndall was convicted of inciting racial hatred

Incitement to ethnic or racial hatred is a crime under the laws of several countries.

Australia

In Australia, the Racial Hatred Act 1995 amends the Racial Discrimination Act 1975, inserting Part IIA – Offensive Behaviour Because of Race, Colour ...

and sentenced to a year's imprisonment; he served only four months before his release. In 1987, the BNP opened discussions with an NF faction, the National Front Support Group (NFSG), to discuss the possibility of a merger, but the NFSG decided against it, remaining cautious about Tyndall's total domination of the BNP.

By 1988, ''Searchlight'' reported that the party's membership had declined to around 1,000. Tyndall responded by trying to raise finances, calling for greater sales of their newspaper and increasing the price of membership by 50%. He also promised that he would make the BNP the largest extreme-right group in the UK and that he would establish a professional headquarters for the party. This was achieved in 1989, as a party headquarters was opened in Welling

Welling is an area of South East London, England, in the London Borough of Bexley, west of Bexleyheath, southeast of Woolwich and of Charing Cross. Before the creation of Greater London in 1965, it was in the historical county of Kent.

...

, Southeast London, an area chosen because it was a recipient of significant 'white flight

White flight or white exodus is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the terms became popular in the United States. They refer ...

' from inner London. That year also witnessed the BNP become the most prominent force on the British far-right as the NF collapsed amid internal arguments and schisms.

1990–1999: Growth of the British National Party

In the early 1990s, a paramilitary group known asCombat 18

Combat 18 (C18 or 318) is a neo-Nazi terrorist organisation that was founded in 1992. It originated in the United Kingdom, with ties to movements in Canada and the United States. Since then it has spread to other countries, including Germany ...

(C18) was formed to protect BNP events from anti-fascist protesters. Tyndall was displeased that by 1992, C18 was having an increased influence over the BNP's street activities. Relations between the groups deteriorated such that by August 1993, activists from the BNP and C18 were physically fighting each other. In December 1993, Tyndall issued a bulletin to BNP branches declaring C18 to be a proscribed organisation, furthermore suggesting that it may have been established by agents of the state to discredit the party. To counter C18's influence, he secured the American white nationalist militant William Pierce as a guest speaker at the BNP's annual rally in November 1995.

Tyndall had observed the electoral success achieved by Jean-Marie Le Pen

Jean Louis Marie Le Pen (, born 20 June 1928) is a French far-right politician who served as President of the National Front from 1972 to 2011. He also served as Honorary President of the National Front from 2011 to 2015.

Le Pen graduated fro ...

and the French National Front during the 1980s and hoped that by learning from their activities he could improve the BNP's electoral prospects. He saw the issue as being one of credibility among the electorate, declaring that "we should be looking for ways to overcome our present image of weakness and smallness". He ignored the significant impact that had been achieved by the French NF through moderating its policies and thereby gaining greater respectability

RespectAbility is an American nonpartisan nonprofit organization dedicated to empowerment and self-advocacy for individuals with disabilities. Its official mission is to fight stigmas and advance opportunities for people with disabilities. Sta ...

among the electorate. While Tyndall had sought to keep skinheads and football hooligans out of the BNP, he still kept a range of Holocaust deniers

Holocaust denial is an antisemitic conspiracy theory that falsely asserts that the Nazi genocide of Jews, known as the Holocaust, is a myth, fabrication, or exaggeration. Holocaust deniers make one or more of the following false statements:

* ...

and convicted criminals close to him. He expressed the view that "we should not be looking for ways of applying ideological cosmetic surgery to ourselves in order to make our features more appealing to our public". Conversely, in the early 1990s a 'moderniser' faction emerged in the party that favoured a more electorally palatable strategy and an emphasis on building grassroots support to win local elections. They were impressed by Le Pen's move to disassociate his party from biological racism and focus on the perceived cultural incompatibility of different racial groups. Tyndall opposed many of the modernisers' ideas and sought to stem their growing influence in the party,

In the 1992 general election, the party stood 13 candidates. Tyndall stood in Bow and Poplar, gaining 3% of the vote.

In a council by-election in September 1993, the BNP gained one council seat—won by Derek Beackon

Derek William Beackon is a British far-right politician. He is currently a member of the British Democratic Party (BDP), and a former member of the British National Party (BNP) and National Front. In 1993, he became the BNP's first elected counc ...

in the East London neighbourhood of Millwall

Millwall is a district on the western and southern side of the Isle of Dogs, in east London, England, in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It lies to the immediate south of Canary Wharf and Limehouse, north of Greenwich and Deptford, eas ...

—after a campaign that targeted the anger of local whites over the perceived preferential treatment received by Bangladeshi migrants in social housing

Public housing is a form of housing tenure in which the property is usually owned by a government authority, either central or local. Although the common goal of public housing is to provide affordable housing, the details, terminology, def ...

.

At the time Tyndall described this as the BNP's "moment in history", deeming it a sign that the party was entering the political mainstream. Following an anti-BNP campaign launched by anti-fascist and local religious groups it lost its Millwall seat during the 1994 local elections.

Tyndall stood as the BNP candidate in the 1994 Dagenham by-election, in which he gained 9% of the vote and had his

Tyndall stood as the BNP candidate in the 1994 Dagenham by-election, in which he gained 9% of the vote and had his electoral deposit In an electoral system, a deposit is the sum of money that a candidate for an elected office, such as a seat in a legislature, is required to pay to an electoral authority before they are permitted to stand for election.

In the typical case, the de ...

returned. This was the first time that an extreme right candidate had retained their deposit since Webster's 1973 showing for the NF in West Bromwich

West Bromwich ( ) is a market town in the borough of Sandwell, West Midlands, England. Historically part of Staffordshire, it is north-west of Birmingham. West Bromwich is part of the area known as the Black Country, in terms of geography, ...

.

In the 1997 general election, the party stood over fifty candidates. Tyndall stood in the East London constituency of Poplar and Canning Town

Poplar and Canning Town was a borough constituency represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It elected one Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (M ...

, where he received 7.26% of the vote. Tyndall was attacked and badly beaten by anti-fascists at an election meeting in Stratford, East London. He was also photographed with the London nail bomber, David Copeland

The 1999 London nail bombings were a series of bomb explosions in London, England. Over three successive weekends between 17 and 30 April 1999, homemade nail bombs were detonated respectively in Brixton in South London; at Brick Lane, Spitalfiel ...

. Tyndall claimed that following the election, the party received between 2,500 and 3,000 enquiries—roughly the same as they had received after the 1983 general election—although far fewer of these enquirers became members.

The party was stagnating, and Tyndall's "political career was now on borrowed time".

After the BNP's poor performance at the 1997 general election, opposition to Tyndall's leadership grew. His position was damaged by a lack of financial transparency in the party, with concerns being raised that large donations to the party had been used instead by Tyndall for personal expenses. The modernisers challenged his control of the party, resulting in its first ever leadership election, held in October 1999. Tyndall was challenged by Nick Griffin

Nicholas John Griffin (born 1 March 1959) is a British politician and white supremacist who represented North West England as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) from 2009 to 2014. He served as chairman and then president of the far-righ ...

, who offered an improved administration, financial transparency and greater support for local branches. 80% of party members voted, with two-thirds backing Griffin; Tyndall had secured only 411 votes, representing 30% of the total membership. Tyndall accepted his defeat with equanimity and stood down as chairman. He stated that he would become "an ordinary member", telling his supporters that "we have all got to pull together in the greater cause of race and nation".

1999–2005: Final years

Tyndall remained a member of the BNP and continued to support it in the pages of ''Spearhead''. But Griffin sought to restrain Tyndall's ongoing influence in the party, curtailing the distribution of ''Spearhead'' among BNP members and instead emphasising his own magazine, ''Identity'', which was established in January 2000. To combat the influence of declining sales, Tyndall established the group 'Friends of ''Spearhead, whose members were asked to contribute £10 a month. By 2000, Tyndall was beginning to agitate against Griffin's leadership, criticising the establishment of the party's Ethnic Liaison Committeewhich had one half-Turkish member (Lawrence Rustem)as a move towards admitting non-whites into the party. He was also critical of Griffin's abandonment of the party's idea of compulsory removal of migrants and non-whites from the country, believing that if they stayed in a segregated system then Britain would resembleapartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

-era South Africa, which he did not think was preferable. His main criticisms were focused not on the party's changing direction, but on Griffin's character itself, portraying him as unscrupulous and self-centred. Tyndall was determined to retake control of the party, and in this was supported by a group of party hardliners. During a proposed leadership challenge, Tyndall put forward his name, although withdrew it following the 2001 general election when Griffin led the BNP to a clear growth in electoral support. Tyndall nevertheless believed that the BNP's electoral success had less to do with Griffin's reforms and more to do with external factors such as the 2001 Oldham riots. In turn, Griffin criticised Tyndall in the pages of ''Identity'', claiming that the latter was committed to "the sub-Mosleyite wackiness of Arnold Leese's Imperial Fascist League and the Big Government mania of the 1930s". Griffin expelled Tyndall from the party in August 2003, but had to allow his return following an out-of-court settlement shortly after.

Tyndall gave a speech at a BNP event in which he claimed that Asians and Africans had only produced "black magic, witchcraft, voodoo, cannibalism and Aids", also attacking the Jewish leader of the Conservative Party, Michael Howard

Michael Howard, Baron Howard of Lympne (born Michael Hecht; 7 July 1941) is a British politician who served as Leader of the Conservative Party and Leader of the Opposition from November 2003 to December 2005. He previously held cabinet posi ...

, as an "interloper, this immigrant or son of immigrants, who has no roots at all in Britain". The speech was filmed by undercover investigator Jason Gwynne

Jason Gwynne is a journalist, most widely known for his 2004 documentary on the British National Party (BNP). The documentary was based on undercover footage gathered by Gwynne who posed as a football hooligan looking to get involved in far-righ ...

and included in a 2004 BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by populati ...

Magistrates' Court two days later. He was survived by his wife and his daughter, Marina.

Policies and views

Tyndall has been described as a racial nationalist, and a British nationalist, as well as afascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

, neo-fascist

Neo-fascism is a post-World War II far-right ideology that includes significant elements of fascism. Neo-fascism usually includes ultranationalism, racial supremacy, populism, authoritarianism, nativism, xenophobia, and anti-immigration s ...

, and a neo-Nazi. Tyndall adhered to neo-Nazism during the 1960s, although from the 1970s onward he increasingly concealed this behind the rhetoric of "British patriotism". According to Thurlow, this was because by this time Tyndall had realised that "open Nazism was counter-productive" to his cause. This was in accordance with a wider trend among Britain's far-right to avoid the term "British fascism", with its electorally unpalatable connotations and instead refer to "British nationalism" in its public appeals. Sykes stated that Tyndall split with Jordan because—in contrast to the latter's neo-Nazi focus on pan-'Aryan' unity—he "thought more traditionally in terms of British nationalism, the British race and the British Empire". Jordan himself accused Tyndall of being "an extreme Tory imperialist, a John Bull

John Bull is a national personification of the United Kingdom in general and England in particular, especially in political cartoons and similar graphic works. He is usually depicted as a stout, middle-aged, country-dwelling, jolly and matter- ...

, unable to recognise the call of race beyond Britain's frontiers".

Tyndall later described his membership of these openly neo-Nazi groups as a "youthful indiscretion". He expressed the view that while he regretted his involvement in them, he was not ashamed of having done so: "though some of my former beliefs were mistaken, I will never acknowledge that there was anything dishonourable about holding them." As leader of the NF he continued to openly approve of Hitler's social and economic programme and well as his policies of German territorial expansion. In his 1988 autobiography ''The Eleventh Hour'', he stated that while he thought that "many of itler'sintentions were good ones and many of his achievements admirable", he did not think "that it is right for a British movement belonging to an entirely different phase of history to model itself on the movement of Hitler".

Following this shift away from overt allegiance to Nazism, Tyndall's supporters and detractors continued to dispute whether he remained a convinced Nazi. Academic commentators consider that his basic ideological world-view did not change. In 1981, Nigel Fielding stated that while Tyndall's views had "moderated remarkably", in the NF he had still "preserve and defend d "those traits which were the hallmark" of earlier neo-Nazi groups. Walker noted that in October 1975 Tyndall wrote articles for ''Spearhead'' which had clearly "returned to the language and ideology of the Nazi days", and that another article printed the previous month was "pure Nazism in that it reflects exactly the mood and spirit of ''Mein Kampf''." The historian Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke

Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke (15 January 195329 August 2012) was a British historian and professor of Western esotericism at the University of Exeter, best known for his authorship of several scholarly books on the history of Germany between the W ...

stated that Tyndall simply "cloaked his former extremism in British nationalism", while the journalist Daniel Trilling

Daniel Trilling is a British journalist, editor and author. He was the editor of ''New Humanist'' magazine from 2013 to 2019. He writes about migration, nationalism and human rights and is the author of ''Lights in the Distance: exile and refuge ...

commented that "Tyndall's claim to have moderated his views was merely expedient". On his death, ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' stated that Tyndall had remained "a racist, violent neo-Nazi to the end", while Trilling described Tyndall as having had "a long pedigree in the most extreme and violent quarters of Britain's far right".

The political scientist Nigel Copsey believed that Chesterton had been the "seminal influence" on Tyndall's thought. Thurlow disagreed, arguing that Tyndall had been influenced less by Chesterton and Mosley and more by a third figure in Britain's "fascist tradition", Arnold Leese. Thurlow noted that Tyndall adopted Leese's "political intransigence… his refusal to compromise with political reality and his willingness to martyr himself for his beliefs". According to Trilling, the "two guiding stars in… Tyndall's political universe" were Hitler and the British Empire. In contrast to many of his contemporaries in the British far-right, Tyndall was "thoroughly indifferent" to the ideas of the Nouvelle Droite

The Nouvelle Droite (; en, "New Right"), sometimes shortened to the initialism ND, is a far-right political movement which emerged in France during the late 1960s. The Nouvelle Droite is at the origin of the wider European New Right (ENR). Vario ...

, a French extreme-right movement which had emerged in the 1960s. Whereas the Nouvelle Droite sought to move away from the approach adopted by the fascist movements of the 1930s and 1940s, Tyndall remained wedded to white racial nationalism, anti-Semitic conspiracy theories and nostalgia for the British Empire, all approaches generally repudiated by the Nouvelle Droite.

Race and nationalism

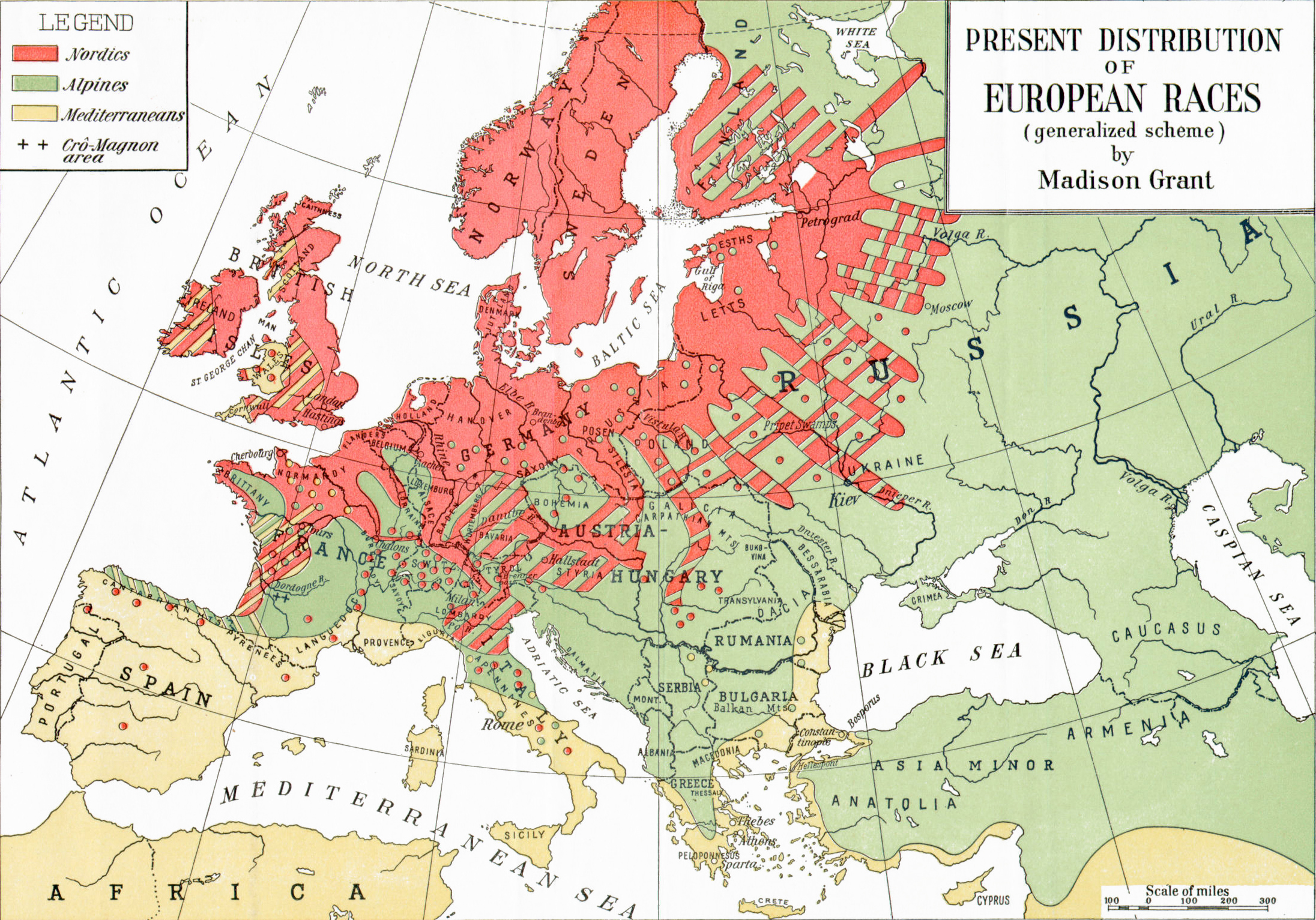

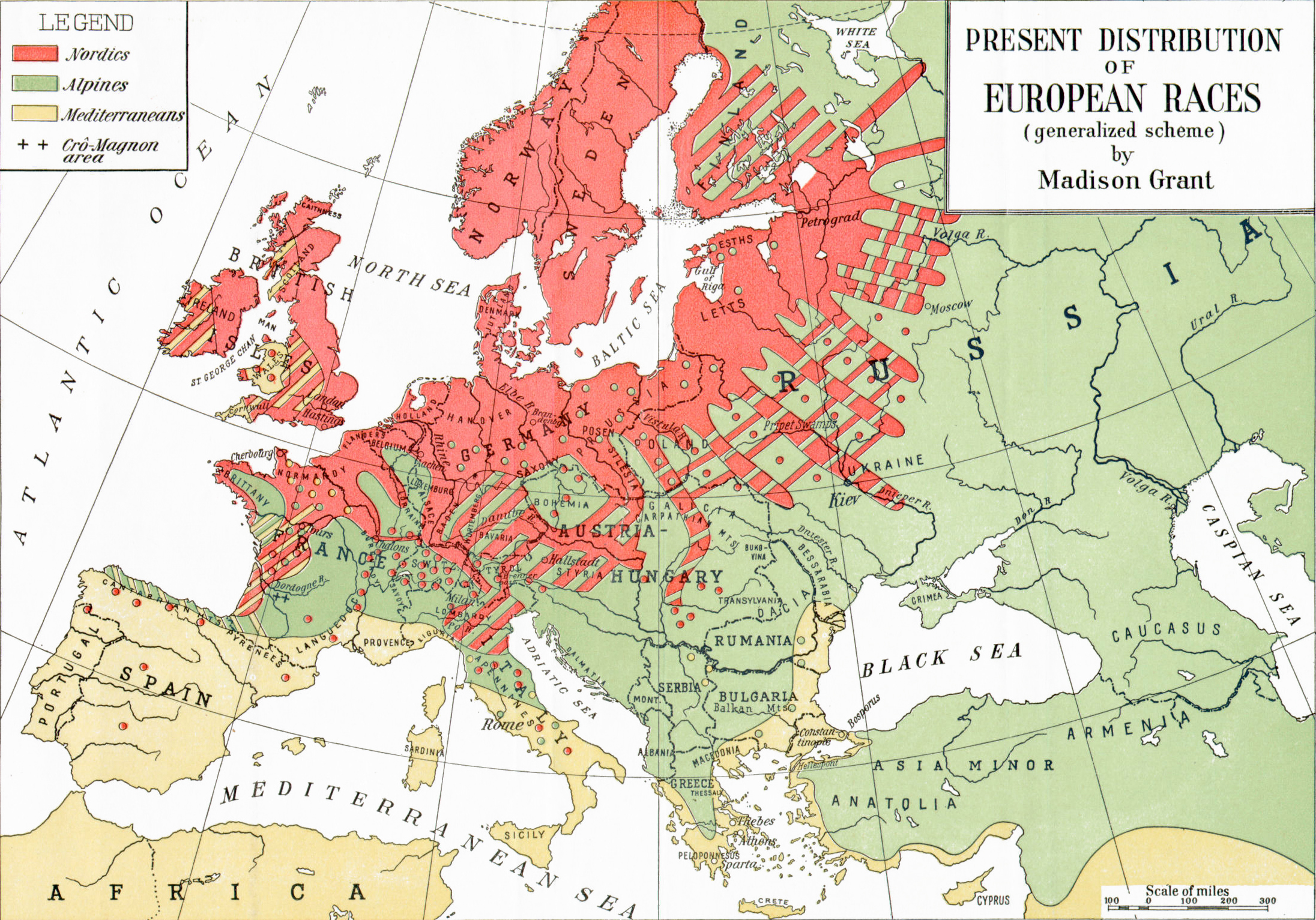

Tyndall had "deeply entrenched" biologically racist views, akin to those of earlier fascists like Hitler and Leese. He believed that there was a biologically distinct white-skinned "British race" which was one branch of a wider

Tyndall had "deeply entrenched" biologically racist views, akin to those of earlier fascists like Hitler and Leese. He believed that there was a biologically distinct white-skinned "British race" which was one branch of a wider Nordic race

The Nordic race was a racial concept which originated in 19th century anthropology. It was considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race, claiming th ...

. Tyndall was of the view that race defined a nation and that "if that is lost we will have no nation in the future." He believed the Nordic race to be superior to others, and under his leadership, the BNP promoted a variety of pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable claim ...

claims in support of white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...