John Surratt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

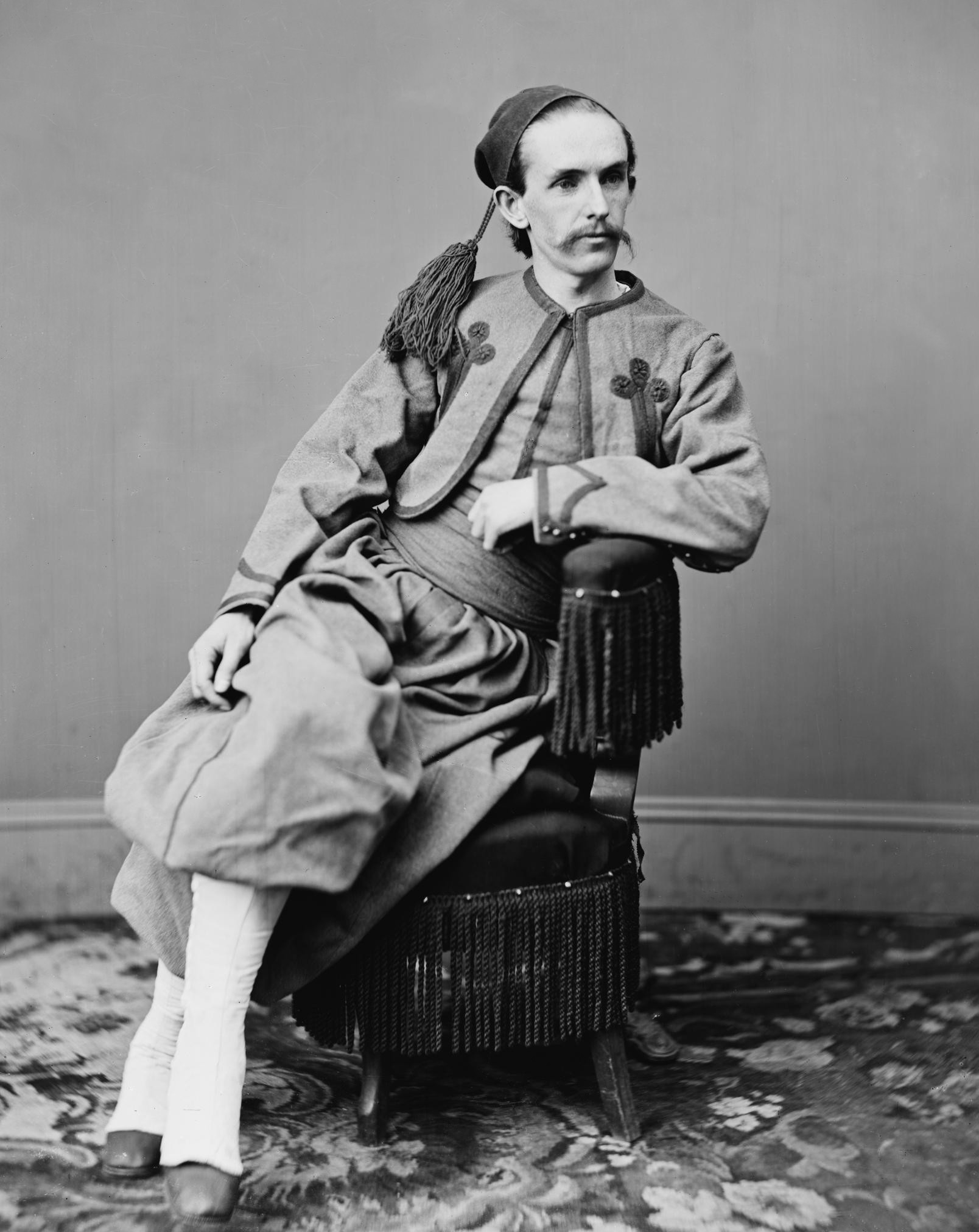

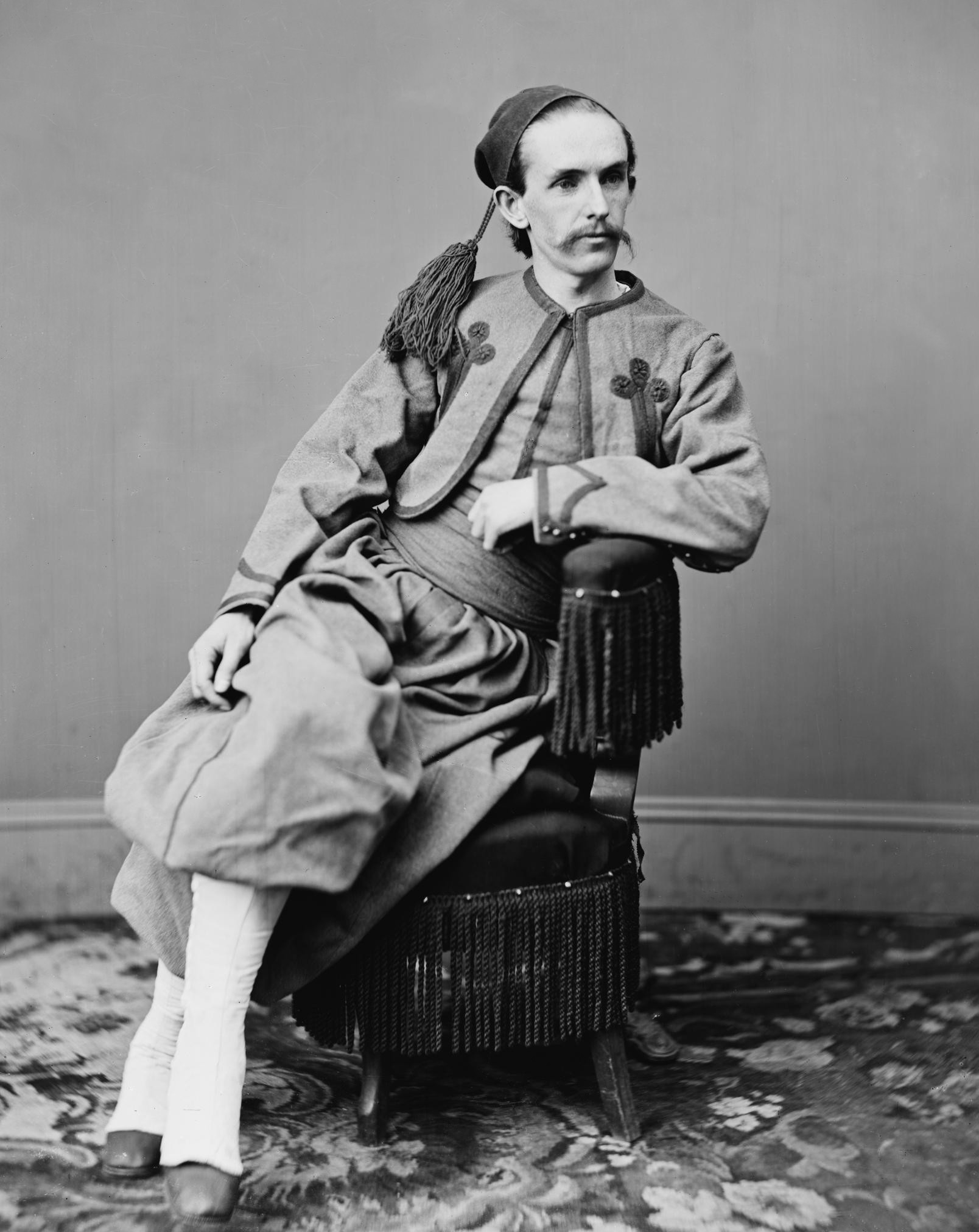

John Harrison Surratt Jr. (April 13, 1844 – April 21, 1916) was an American Confederate spy who was accused of plotting with

St. Joseph’s Catholic Church

not only visiting to collect money for the church, but also a member of the ‘Texas Fancy Table’ at the 1895 Church Fair, and even donating a stained glass window. Maria was also the daughter of Richard Padian for whom Padonia Road, as well as the old

Eighteen months after his mother was hanged, Surratt was tried in a

Eighteen months after his mother was hanged, Surratt was tried in a

John Surratt

*A ttps://web.archive.org/web/20090720233738/http://www.concharto.org/search/eventsearch.htm?_tag=john+surratt&_maptype=0 map and timelineof John Surratt's two-year flight and eventual capture

John H. Surratt's career as a teacher after the assassination aftermath

{{DEFAULTSORT:Surratt, John 1844 births 1916 deaths Confederate States Army soldiers People from Washington, D.C. Maryland postmasters Lincoln assassination conspirators People of Washington, D.C., in the American Civil War Deaths from pneumonia in Maryland St. Charles College alumni American Roman Catholics Papal Zouaves Burials in Maryland

John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838 – April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who assassinated United States President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the prominent 19th-century Booth the ...

to kidnap U.S. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

; he was also suspected of involvement in the Abraham Lincoln assassination. His mother, Mary Surratt

Mary Elizabeth Jenkins SurrattCashin, p. 287.Steers, 2010, p. 516. (1820 or May 1823 – July 7, 1865) was an American boarding house owner in Washington D.C., Washington, D.C., who was convicted of taking part in the conspiracy (crime), ...

, was convicted of conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, is a secret plan or agreement between persons (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder or treason, especially with political motivation, while keeping their agr ...

by a military tribunal and hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging in ...

; she owned the boarding house that the conspirators used as a safe house and to plot the scheme.

He avoided arrest immediately after the assassination by fleeing to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tota ...

and then to Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

. He thus avoided the fate of the other conspirators, who were hanged. He served briefly as a Pontifical Zouave but was recognized and arrested. He escaped to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

but was eventually arrested and extradited. By the time of his trial, the statute of limitations

A statute of limitations, known in civil law systems as a prescriptive period, is a law passed by a legislative body to set the maximum time after an event within which legal proceedings may be initiated. ("Time for commencing proceedings") In m ...

had expired on most of the potential charges which meant that he was never convicted of anything.

Early life

He was born in 1844, to John Harrison Surratt Sr. and Mary Elizabeth Jenkins Surratt, in what is today Congress Heights. His baptism took place in 1844 at St. Peter's Church, Washington, D.C. In 1861, he was enrolled at St. Charles College, where he was studying for the priesthood and also metLouis Weichmann

Louis J. Weichmann (September 29, 1842 – June 5, 1902) was an American clerk who was one of the chief witnesses for the prosecution in the trial following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Previously, he had been also a suspect in the con ...

. When his father suddenly died in 1862, Surratt was appointed the postmaster for Surrattsville, Maryland

Clinton is an unincorporated census-designated place (CDP) in Prince George's County, Maryland, United States. Clinton was formerly known as Surrattsville until after the time of the Civil War. The population of Clinton was 38,760 at the 2020 cen ...

.

Plot to kidnap Lincoln

Surratt served as a Confederate Secret Service courier and spy. After he had been carrying dispatches about Union troop movements across thePotomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands of West Virginia, Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Datas ...

. Dr. Samuel Mudd

Samuel Alexander Mudd Sr. (December 20, 1833 – January 10, 1883) was an American physician who was imprisoned for conspiring with John Wilkes Booth concerning the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

Mudd worked as a doctor and tobacco far ...

introduced Surratt to Booth on December 23, 1864, and Surratt agreed to help Booth kidnap Lincoln. The meeting took place at the National Hotel, in Washington, D.C., where Booth lived.

Booth's plan was to seize Lincoln and take him to Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

, to exchange him for thousands of Confederate prisoners of war. On March 17, 1865, Surratt and Booth, along with their comrades, waited in ambush for Lincoln's carriage to leave the Campbell General Hospital to return to Washington. However, Lincoln had changed his mind and remained in Washington.

William H. Crook

William Henry Crook (October 15, 1839March 13, 1915) was one of President Abraham Lincoln's bodyguards in 1865. After Lincoln's assassination (while Crook was off duty), he continued to work in the White House for a total of more than 50 years, ...

, one of Lincoln's bodyguards, claimed that Surratt had boarded the ''River Queen'' shortly before the Third Battle of Petersburg, using the name of Smith and demanding to see Lincoln (who was aboard at the time). Crook later stated his belief that Surratt "was seeking an opportunity to assassinate the President at this time".

Assassination of Lincoln

After the assassination of Lincoln, on April 14, 1865, Surratt denied any involvement and said that he was then inElmira, New York

Elmira () is a city and the county seat of Chemung County, New York, United States. It is the principal city of the Elmira, New York, metropolitan statistical area, which encompasses Chemung County. The population was 26,523 at the 2020 census ...

. He was one of the first people suspected of the attempt to assassinate Secretary of State William H. Seward, but the culprit was soon discovered to be Lewis Powell.

In hiding

When he learned of the assassination, Surratt fled toMontreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

, Canada East

Canada East (french: links=no, Canada-Est) was the northeastern portion of the United Province of Canada. Lord Durham's Report investigating the causes of the Upper and Lower Canada Rebellions recommended merging those two colonies. The new c ...

, arriving on April 17, 1865. He then went to St. Liboire, where a Catholic priest, Father Charles Boucher, gave him sanctuary. Surratt remained there while his mother was arrested, tried, and hanged in the United States for conspiracy.

Aided by ex-Confederate agents Beverly Tucker and Edwin Lee, Surratt, disguised, booked passage under a false name. He landed at Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

in September, where he lodged in the oratory at the Church of the Holy Cross.

Surratt would later serve for a time in the Ninth Company of the Pontifical Zouaves, in the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct Sovereignty, sovereign rule of ...

, under the name John Watson.

An old friend, Henri Beaumont de Sainte-Marie, recognized Surratt and notified papal officials and the US minister in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, Rufus King

Rufus King (March 24, 1755April 29, 1827) was an American Founding Father, lawyer, politician, and diplomat. He was a delegate for Massachusetts to the Continental Congress and the Philadelphia Convention and was one of the signers of the Un ...

. Henri was introduced to John Surratt and Louis Weichmann

Louis J. Weichmann (September 29, 1842 – June 5, 1902) was an American clerk who was one of the chief witnesses for the prosecution in the trial following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Previously, he had been also a suspect in the con ...

in April 1863 at St. Joseph's Catholic School in the town then known as Ellengowan or Little Texas (now a part of Cockeysville

Cockeysville is a census-designated place (CDP) in Baltimore County, Maryland, United States. The population was 20,776 at the 2010 census.

History

Cockeysville was named after the Cockey family who helped establish the town. Thomas Cockey (1676� ...

, Maryland) by Father Mahoney. Henri taught at the school for five months in 1863 having been hired by Fr. Mahoney at the request of Maria Padian. Although Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

, Henri wanted to join the Confederate Army when the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

broke out. Henri traveled to New York and boarded a ship that was to run the blockade of the Southern States Southern States may refer to:

*The independent states of the Southern hemisphere

United States

* Southern United States, or the American South

* Southern States Cooperative, an American farmer-owned agricultural supply cooperative

* Southern Stat ...

. “The ship, however, was captured by a United States war steamer and Sainte Marie with his fellow voyagers was thrown into Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry is a historical American coastal pentagonal bastion fort on Locust Point, now a neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland. It is best known for its role in the War of 1812, when it successfully defended Baltimore Harbor from an attack ...

as a prisoner of war.” Henri was released through the intervention of the English Consul since he was a British subject. Henri was then stranded in Baltimore with little money and his plan was to move into a cheap boarding house and get a job to earn some money. Fate intervened and “one day an old farmer living in the country outside of Baltimore came to his place.” Henri related his misfortunes to the old farmer, who took mercy on him and gave him a job on his farm. Henri accepted the job offer. It was on this farm that Maria Padian “happened to pay a visit to Sainte Marie’s benefactor to collect money for the church at Little Texas.” Maria was a very active member oSt. Joseph’s Catholic Church

not only visiting to collect money for the church, but also a member of the ‘Texas Fancy Table’ at the 1895 Church Fair, and even donating a stained glass window. Maria was also the daughter of Richard Padian for whom Padonia Road, as well as the old

North Central Railroad

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' i ...

stop Padonia Station, was named. By all accounts, Maria, single and for whom most eligible men her age were off fighting in the Civil War, was bowled over by Henri and strongly “captivated with his polished manners, good looks, handsome brown eyes, refined conversation, and general education, and listened early to the recital of his adventures.” and made a plea to Fr. Mahoney to hire her new friend for the school.

On November 7, 1866, Surratt was arrested and sent to the Velletri

Velletri (; la, Velitrae; xvo, Velester) is an Italian ''comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Rome, approximately 40 km to the southeast of the city centre, located in the Alban Hills, in the region of Lazio, central Italy. Neighbouring co ...

prison. He escaped and lived with the supporters of Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

, who gave him safe passage. Surratt traveled to the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and ...

and posed as a Canadian citizen named Walters. He booked passage to Alexandria, Egypt

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, but was arrested there by US officials on November 23, 1866, still in his Pontifical Zouaves uniform. He returned to the US on the USS ''Swatara'' to the Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy.

The Yard currently serves as a ceremonial and administra ...

in early 1867.

Trial

Eighteen months after his mother was hanged, Surratt was tried in a

Eighteen months after his mother was hanged, Surratt was tried in a Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; ...

civilian court. It was not before a military commission, unlike the trials of his mother and the others, as a US Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

decision, '' Ex parte Milligan'', had declared the trial of civilians before military tribunals to be unconstitutional if civilian courts were still open.

Judge David Carter presided over Surratt's trial, and Edwards Pierrepont conducted the federal government's case against him. Surratt's lead attorney, Joseph Habersham Bradley, admitted Surratt's part in plotting to kidnap Lincoln but denied any involvement in the murder plot. After two months of testimony, Surratt was released after a mistrial; eight jurors had voted not guilty, four voted guilty.

The statute of limitations on charges other than murder had run out, and Surratt was released on bail.

Later life

Surratt tried to farm tobacco and then taught at the Rockville Female Academy. In 1870, as one of the last surviving members of the conspiracy, Surratt began a much-heralded public lecture tour. On December 6, at a small courthouse in Rockville, Maryland, in a 75-minute speech, Surratt admitted his involvement in the scheme to kidnap Lincoln. However, he maintained that he knew nothing of the assassination plot and reiterated that he was then in Elmira. He disavowed any participation by the Confederate government, reviled Weichmann as a "perjurer" who was responsible for his mother's death and said his friends had kept from him the seriousness of her plight in Washington. After that revelation, it was reported in Washington's ''Evening Star'' that the band played "Dixie

Dixie, also known as Dixieland or Dixie's Land, is a nickname for all or part of the Southern United States. While there is no official definition of this region (and the included areas shift over the years), or the extent of the area it cove ...

" and a small concert was improvised, with Surratt the center of female attention.

Three weeks later, Surratt was to give a second lecture in Washington, but it was canceled because of public outrage.

Surratt later took a job as a teacher in St. Joseph Catholic School in Emmitsburg, Maryland

Emmitsburg is a town in Frederick County, Maryland, United States, south of the Mason-Dixon line separating Maryland from Pennsylvania. Founded in 1785, Emmitsburg is the home of Mount St. Mary's University. The town has two Catholic pilgrimag ...

. In 1872, Surratt married Mary Victorine Hunter, a second cousin of Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key (August 1, 1779January 11, 1843) was an American lawyer, author, and amateur poet from Frederick, Maryland, who wrote the lyrics for the American national anthem "The Star-Spangled Banner". Key observed the British bombardment ...

. The couple lived in Baltimore and had seven children.

Some time after 1872, he was hired by the Baltimore Steam Packet Company

The Baltimore Steam Packet Company, nicknamed the , was an American steamship line from 1840 that provided overnight steamboat service on Chesapeake Bay, primarily between Baltimore, Maryland, and Norfolk, Virginia. Called a " packet" for the ma ...

. He rose to freight auditor and, ultimately, treasurer of the company. Surratt retired from the steamship line in 1914 and died of pneumonia in 1916, at the age of 72.

He was buried in the New Cathedral Cemetery

The New Cathedral Cemetery is a Roman Catholic cemetery, with 125 acres, located on the westside of Baltimore, Maryland, at 4300 Old Frederick Road. It is the final resting place of 110,000 people, including numerous individuals who played impo ...

, in Baltimore.

In film

Surratt was portrayed by Johnny Simmons in the 2010Robert Redford

Charles Robert Redford Jr. (born August 18, 1936) is an American actor and filmmaker. He is the recipient of various accolades, including an Academy Award from four nominations, a British Academy Film Award, two Golden Globe Awards, the Ceci ...

film '' The Conspirator''.

See also

* James W. Pumphrey – Surratt introduced Booth to Pumphrey, who supplied Booth's getaway horse.References

Sources

* * * * * *External links

John Surratt

*A ttps://web.archive.org/web/20090720233738/http://www.concharto.org/search/eventsearch.htm?_tag=john+surratt&_maptype=0 map and timelineof John Surratt's two-year flight and eventual capture

John H. Surratt's career as a teacher after the assassination aftermath

{{DEFAULTSORT:Surratt, John 1844 births 1916 deaths Confederate States Army soldiers People from Washington, D.C. Maryland postmasters Lincoln assassination conspirators People of Washington, D.C., in the American Civil War Deaths from pneumonia in Maryland St. Charles College alumni American Roman Catholics Papal Zouaves Burials in Maryland