John Seward Johnson II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Seward Johnson II (April 16, 1930 – March 10, 2020), also known as J. Seward Johnson Jr. and Seward Johnson, was an American artist known for ''

Johnson worked for

Johnson worked for  * ''Copyright Infringement'' (1994), at Grounds for Sculpture (a facility founded by Johnson) is a sculpture that he named to flaunt his disdain for criticism of his copies of the iconic works of fine art artists with international recognition. It represents the fine artist

* ''Copyright Infringement'' (1994), at Grounds for Sculpture (a facility founded by Johnson) is a sculpture that he named to flaunt his disdain for criticism of his copies of the iconic works of fine art artists with international recognition. It represents the fine artist

Port surrenders in the battle against kitsch

", ''San Diego Union-Tribune,'' March 11, 2007. however, the Jorgensen photographic image does not extend low enough to include the lower legs and shoes of the subjects, revealed in * ''Big Sister'', just outside the Pig 'N' Whistle pub and Michael's Restaurant at 123 Eagle Street, part of the ''Celebrating the Familiar'' series

*''Morris Frank and Buddy'' (2005) - a statue of the co-founder of

* ''Big Sister'', just outside the Pig 'N' Whistle pub and Michael's Restaurant at 123 Eagle Street, part of the ''Celebrating the Familiar'' series

*''Morris Frank and Buddy'' (2005) - a statue of the co-founder of  * ''Newspaper Reader'', at the entrance to Steinman Park, Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

* ''

* ''Newspaper Reader'', at the entrance to Steinman Park, Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

* '' ''Magic Fountain'' stands outside

''Magic Fountain'' stands outside

trompe-l'œil

''Trompe-l'œil'' ( , ; ) is an artistic term for the highly realistic optical illusion of three-dimensional space and objects on a two-dimensional surface. ''Trompe l'oeil'', which is most often associated with painting, tricks the viewer into ...

'' painted bronze statues

Bronze is the most popular metal for cast metal sculptures; a cast bronze sculpture is often called simply "a bronze". It can be used for statues, singly or in groups, reliefs, and small statuettes and figurines, as well as bronze elements ...

. He was a grandson of Robert Wood Johnson I

Robert Wood Johnson I (February 20, 1845 – February 7, 1910) was an American industrialist. He was also one of the three brothers who founded Johnson & Johnson.

Early life

Johnson was born in Carbondale, Pennsylvania. His father was Sylvest ...

, the co-founder of Johnson & Johnson

Johnson & Johnson (J&J) is an American multinational corporation founded in 1886 that develops medical devices, pharmaceuticals, and consumer packaged goods. Its common stock is a component of the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the company i ...

, and of Colonel Thomas Melville Dill

Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Melville Dill OBE (23 December 1876 – 7 March 1945) was a prominent Bermudian lawyer, politician, and soldier.

Early life

Dill was born in Devonshire Parish, in the British Imperial fortress colony of Bermuda, the ...

of Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

.

He designed life-size bronze statues that were casting

Casting is a manufacturing process in which a liquid material is usually poured into a mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. The solidified part is also known as a ''casting'', which is ejected ...

s of living people, depicting them engaged in day-to-day activities. A large staff of technicians did the fabrication of the works he designed. Computers and digital technology often were used in the manufacturing process. Sometimes the manufacture was contracted in China. He was the founder of Grounds For Sculpture

Grounds For Sculpture (GFS) is a sculpture park and museum located in Hamilton, New Jersey. It is located on the former site of Trenton Speedway. Founded in 1992 by John Seward Johnson II, the venue is dedicated to promoting an understanding of ...

, a sculpture park and museum located in Hamilton Township, Mercer County, New Jersey

Hamilton Township is a township in Mercer County, New Jersey, United States. It is the largest suburb of Trenton, the state's capital, which is located to the township's west. The township is within the New York metropolitan area as defined ...

.

Early life

Johnson was born in New Brunswick,New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

on April 16, 1930. His father was John Seward Johnson I

John Seward Johnson I (July 14, 1895 – May 23, 1983) was one of the sons of Robert Wood Johnson I (co-founder of Johnson & Johnson). He was also known as J. Seward Johnson Sr. and Seward Johnson. He was a longtime executive and director of Jo ...

, and his mother was Ruth Dill, the sister of actress Diana Dill, making him a first cousin of actor Michael Douglas

Michael Kirk Douglas (born September 25, 1944) is an American actor and film producer. He has received numerous accolades, including two Academy Awards, five Golden Globe Awards, a Primetime Emmy Award, the Cecil B. DeMille Award, and the AF ...

. Johnson grew up with five siblings: Mary Lea Johnson Richards

Mary Lea Johnson Richards (August 20, 1926 – May 3, 1990) was an American heiress, entrepreneur, and Broadway producer. She was a granddaughter of Robert Wood Johnson I (co-founder of Johnson & Johnson), and of Bermudan politician, soldier, an ...

, Elaine Johnson, Diana Melville Johnson, Jennifer Underwood Johnson, and James Loring "Jimmy" Johnson. His parents divorced around 1937. His father remarried two years later, producing his only brother, Jimmy Johnson, making him an uncle to film

A film also called a movie, motion picture, moving picture, picture, photoplay or (slang) flick is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, feelings, beauty, or atmosphere ...

director Jamie Johnson.

Johnson attended Forman School

The Forman School is a co-educational Boarding school, boarding and day school in Litchfield, Connecticut, United States offering a college preparatory program in grades 9 to 12 and a postgraduate year, postgraduate program (PG) exclusively for st ...

for dyslexics. Later, he attended the University of Maine

The University of Maine (UMaine or UMO) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Orono, Maine. It was established in 1865 as the land-grant college of Maine and is the Flagship universities, flagshi ...

, where he majored in poultry husbandry, but did not graduate. Johnson also served four years in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

during the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

.

Career

Johnson worked for

Johnson worked for Johnson & Johnson

Johnson & Johnson (J&J) is an American multinational corporation founded in 1886 that develops medical devices, pharmaceuticals, and consumer packaged goods. Its common stock is a component of the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the company i ...

until 1962, when he was fired by his uncle Robert Wood Johnson II

Robert Wood "General" Johnson II (April 4, 1893 – January 30, 1968) was an American businessman. He was one of the sons of Robert Wood Johnson I, the co-founder of Johnson & Johnson. He turned the family business into one of the world's l ...

, who had turned the family business into one of the world's largest healthcare corporations.

Johnson maintained a studio in Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton is a municipality with a borough form of government in Mercer County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton and Princeton Township, both of whi ...

and later, another at a site in Mercerville, New Jersey that formerly had been used for the New Jersey State Fair

The New Jersey State Fair is a non-profit agricultural fair held every June 18 - July 11 at the Sussex County Fairgrounds in Augusta, New Jersey. The fair has been held in conjunction with the Sussex County Farm and Horse Show since 1999 and dra ...

.

His early artistic efforts focused on painting, after which he turned to sculpture in 1968. Examples of his statues include:

* ''Spring'' (1979), a bronze dedicated in 1979, set in the Crim Dell Woods section of the College of William and Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William III a ...

, Williamsburg, Virginia. Other examples of ''Spring'' castings include the East Brunswick, New Jersey public library and the Fitton Center for Creative Arts in Hamilton, Ohio.

* '' The Awakening'' (1980), his largest and most dramatic work, a five-part statue that depicts a giant trying to free himself from underground. The sculpture was located at Hains Point

Hains Point is located at the southern tip of East Potomac Park between the main branch of the Potomac River and the Washington Channel in southwest Washington, D.C.Map, National Mall Plan Study Area,

Area of Potential Effect, United States Depart ...

in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

for nearly twenty-eight years while still owned by Johnson. It was moved to Prince George's County, Maryland

)

, demonym = Prince Georgian

, ZIP codes = 20607–20774

, area codes = 240, 301

, founded date = April 23

, founded year = 1696

, named for = Prince George of Denmark

, leader_title = Executive

, leader_name = Angela D. Alsobroo ...

in February 2008 and an attempt was made by the new curator to correct some of the scale distortions of the original installation by altering some implied underground connections and placing the parts in different relationships to each other.

* ''Double Check

In chess and other related games, a double check is a check delivered by two pieces simultaneously. In chess notation, it is almost always represented the same way as a single check ("+"), but it is sometimes symbolized by "++" (however, "++" is ...

'' (1982), a statue of a businessman checking his attaché case, formerly located in Liberty Plaza Park across an intersection from the World Trade Center

World Trade Centers are sites recognized by the World Trade Centers Association.

World Trade Center may refer to:

Buildings

* List of World Trade Centers

* World Trade Center (2001–present), a building complex that includes five skyscrapers, a ...

, as part of the public space required by a zoning variance granted to the developer of the adjoining skyscraper. Widely published photographs of the debris-battered and dust-covered statue, were taken following the September 11 terrorist attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercial ...

in 2001. The statue, scars and all, was returned to a prominent corner of the restored and renamed Zuccotti Park

Zuccotti Park (formerly Liberty Plaza Park) is a publicly accessible park in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan, New York City. It is located in a privately owned public space (POPS) controlled by Brookfield Properties and Goldman Sachs. ...

in 2006, again open to the public. Periodically, the statue has been adorned by tourists, pranksters, and even Occupy Wall Street

Occupy Wall Street (OWS) was a protest Social movement, movement against economic inequality and the Campaign finance, influence of money in politics that began in Zuccotti Park, located in New York City's Financial District, Manhattan, Wall S ...

protesters.

* ''Hitchhiker'' (1983), a statue at Hofstra University

Hofstra University is a private university in Hempstead, New York. It is Long Island's largest private university. Hofstra originated in 1935 as an extension of New York University (NYU) under the name Nassau College – Hofstra Memorial of Ne ...

, at the California Avenue gate, near a road leading away from campus.

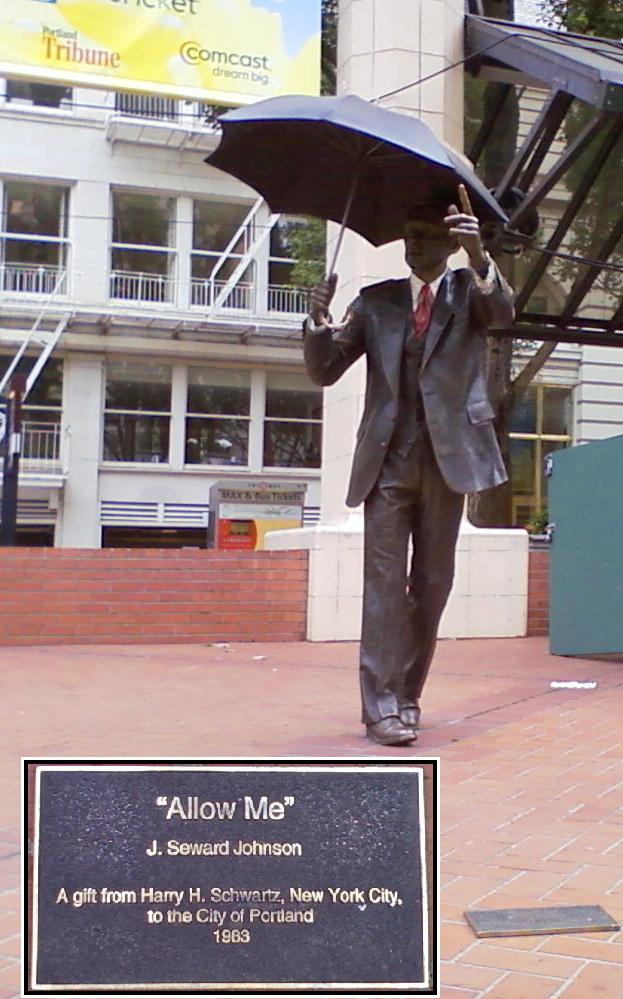

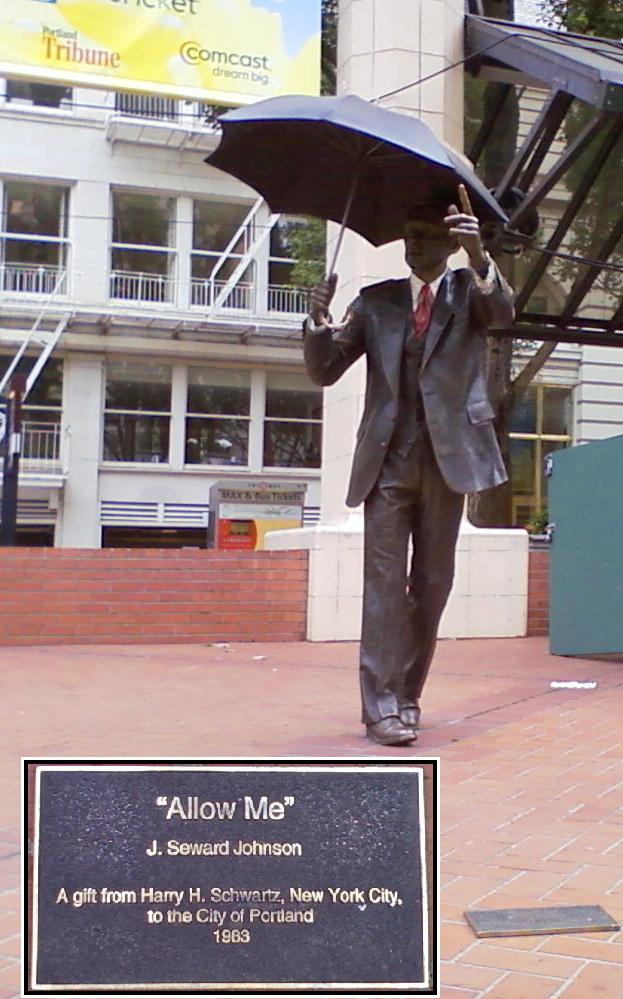

* ''Allow Me'' (Portland, Oregon) (1984), a statue of man holding an umbrella, in Pioneer Courthouse Square

Pioneer Courthouse Square, also known as Portland's living room, is a public space occupying a full city block in the center of downtown Portland, Oregon, United States. Opened in 1984, the square is bounded by Southwest Morrison Street on t ...

in Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous co ...

(part of the '' Allow Me'' series).

* ''Competition'' (1984), a statue of Julie Wier, Fairview Heights, Illinois

Fairview Heights is a city in St. Clair County, Illinois, United States. The population was 17,078 at the 2010 census. Fairview Heights is a dominant shopping center for Southern Illinois and includes numerous shopping plazas and the St. Clair S ...

, chosen to represent the spirit of the people of St. Louis as winner of the "picture yourself as a work of art" contest. Dedicated on June 16, 1984 unsigned St. Louis County Library in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

.

* ''Waiting'' (1988), at Australia Square

Australia Square Tower is an office and retail complex in the central business district of Sydney. Its main address is 264 George Street, and the Square is bounded on the northern side by Bond Street, eastern side by Pitt Street and southern s ...

, Sydney, Australia

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and List of cities in Oceania by population, Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metro ...

* ''Déjeuner Déjà Vu'' (1994), at Grounds for Sculpture

Grounds For Sculpture (GFS) is a sculpture park and museum located in Hamilton, New Jersey. It is located on the former site of Trenton Speedway. Founded in 1992 by John Seward Johnson II, the venue is dedicated to promoting an understanding of ...

in Hamilton Township, Mercer County, New Jersey

Hamilton Township is a township in Mercer County, New Jersey, United States. It is the largest suburb of Trenton, the state's capital, which is located to the township's west. The township is within the New York metropolitan area as defined ...

, a facility founded by Johnson, is a three-dimensional restaging of Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet (, ; ; 23 January 1832 – 30 April 1883) was a French modernist painter. He was one of the first 19th-century artists to paint modern life, as well as a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism.

Born ...

's painting, '' Le déjeuner sur l'herbe''

* ''Copyright Infringement'' (1994), at Grounds for Sculpture (a facility founded by Johnson) is a sculpture that he named to flaunt his disdain for criticism of his copies of the iconic works of fine art artists with international recognition. It represents the fine artist

* ''Copyright Infringement'' (1994), at Grounds for Sculpture (a facility founded by Johnson) is a sculpture that he named to flaunt his disdain for criticism of his copies of the iconic works of fine art artists with international recognition. It represents the fine artist Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet (, ; ; 23 January 1832 – 30 April 1883) was a French modernist painter. He was one of the first 19th-century artists to paint modern life, as well as a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism.

Born ...

, whose work he has copied.

* ''Unconditional Surrender

An unconditional surrender is a surrender in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. It is often demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination or annihilation.

In modern times, unconditional surrenders most ofte ...

'' (a series with several material versions begun in 2005), a spokesperson for Johnson has stated that this series is based on a photograph that is in the public domain

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work

A creative work is a manifestation of creative effort including fine artwork (sculpture, paintings, drawing, sketching, performance art), dance, writing (literature), filmmaking, ...

, ''Kissing the War Goodbye'', by Victor Jorgensen

Victor Jorgensen (July 8, 1913 – June 14, 1994) was a former Navy photo journalist who probably is most notable for taking an instantly iconic photograph of an impromptu scene in Manhattan on August 14, 1945, but from a different angle and in ...

,Robert L. Pincus,Port surrenders in the battle against kitsch

", ''San Diego Union-Tribune,'' March 11, 2007. however, the Jorgensen photographic image does not extend low enough to include the lower legs and shoes of the subjects, revealed in

Alfred Eisenstaedt

Alfred Eisenstaedt (December 6, 1898 – August 23, 1995) was a German-born American photographer and photojournalist. He began his career in Germany prior to World War II but achieved prominence as a staff photographer for ''Life'' magazine af ...

's famous photograph, '' V–J day in Times Square'', that are represented identically in the statue. A spokesperson for ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energ ...

'' has called it a copyright infringement

Copyright infringement (at times referred to as piracy) is the use of works protected by copyright without permission for a usage where such permission is required, thereby infringing certain exclusive rights granted to the copyright holder, s ...

of the latter image. Nonetheless, the first version, a bronze statue in life-size, was placed on temporary exhibition during the 2005 anniversary of V-J Day

Victory over Japan Day (also known as V-J Day, Victory in the Pacific Day, or V-P Day) is the day on which Imperial Japan surrendered in World War II, in effect bringing the war to an end. The term has been applied to both of the days on ...

at the Times Square

Times Square is a major commercial intersection, tourist destination, entertainment hub, and neighborhood in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. It is formed by the junction of Broadway, Seventh Avenue, and 42nd Street. Together with adjacent ...

Information Center near where the original photographs were taken in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

.

:Several slightly differing twenty-five-feet-tall-versions have been constructed in styrofoam

Styrofoam is a trademarked brand of closed-cell extruded polystyrene foam (XPS), commonly called "Blue Board", manufactured as foam continuous building insulation board used in walls, roofs, and foundations as thermal insulation and water barrie ...

and aluminum

Aluminium (aluminum in American and Canadian English) is a chemical element with the symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately one third that of steel. It has ...

with little detail, painted, and put on display by Johnson in San Diego, California

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

, Key West, Florida

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Sigsbee Park, Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Isla ...

, Snug Harbor in New York, and Sarasota, Florida

Sarasota () is a city in Sarasota County on the Gulf Coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The area is renowned for its cultural and environmental amenities, beaches, resorts, and the Sarasota School of Architecture. The city is located in the sout ...

. Their immensity has drawn crowds of viewers at each site although the view of them from nearby is severely limited, essentially allowing a vista of the legs and up the skirt. The statues have been described as kitsch

Kitsch ( ; loanword from German) is a term applied to art and design that is perceived as naïve imitation, overly-eccentric, gratuitous, or of banal taste.

The avant-garde opposed kitsch as melodramatic and superficial affiliation with ...

by one critic. Johnson later would dub the statue "Embracing Peace", which he treated as a double entendre

A double entendre (plural double entendres) is a figure of speech or a particular way of wording that is devised to have a double meaning, of which one is typically obvious, whereas the other often conveys a message that would be too socially ...

when spoken.

:A proposal to establish a permanent location for a copy on the Sarasota bay front generated a heated controversy about the suitability of the statue to the location, suitability as a military service memorial, the permanent placement of any statue on that public property, as well as the particular issues of lack of originality, mechanical construction, copyright infringement, and the kitsch allegations about the statue. In final agreement documents with the purchaser (a private person), Johnson committed the purchase price to cover copyright liability damages in order to have the statue placed. The city was wary of accepting a gift from the purchaser that might result in a financial loss from a possible legal battle that evidenced merit, according to the city attorney.

:In October 2014, French feminist group Osez La Feminisme ! petitioned to have a copy of the statue, erected at a World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

memorial

A memorial is an object or place which serves as a focus for the memory or the commemoration of something, usually an influential, deceased person or a historical, tragic event. Popular forms of memorials include landmark objects or works of a ...

in Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

in September 2014, removed and sent back to the United States, criticizing it as "immortaliing

Ing, ING or ing may refer to:

Art and media

* '' ...ing'', a 2003 Korean film

* i.n.g, a Taiwanese girl group

* The Ing, a race of dark creatures in the 2004 video game '' Metroid Prime 2: Echoes''

* "Ing", the first song on The Roches' 1992 ...

a sexual assault"

:Controversies surrounding the statue still existed in Sarasota at the close of 2021, when the question of whether to place a sign addressing them was presented to the city commission at a public meeting in Sarasota on December 6.

The Seeing Eye

The Seeing Eye, Inc. is a guide dog school located in Morristown, New Jersey, in the United States. Founded in 1929, the Seeing Eye is the oldest guide dog school in the U.S., and one of the largest. The Seeing Eye campus includes administra ...

and the first guide dog

Guide dogs (colloquially known in the US as seeing-eye dogs) are assistance dogs trained to lead blind or visually impaired people around obstacles. Although dogs can be trained to navigate various obstacles, they are red–green colour blin ...

for the blind trained in the US stands in the Morristown Green

Morristown Green, most commonly referred to as the Green, is a historical park located in the center of Morristown, New Jersey. It has an area of two and a half acres and has in the past served as a military base, a militia training ground, ...

in New Jersey. Frank

Frank or Franks may refer to:

People

* Frank (given name)

* Frank (surname)

* Franks (surname)

* Franks, a medieval Germanic people

* Frank, a term in the Muslim world for all western Europeans, particularly during the Crusades - see Farang

Curr ...

is shown giving the "forward" command to his dog.

* ''First Ride'' (2006), a statue of a father helping his young daughter learn to ride a bike, in Carmel, Indiana

Carmel is a suburban city in Indiana immediately north of Indianapolis. With a population of 100,777, the city spans across Clay Township in Hamilton County, Indiana, and is bordered by the White River to the east; the Hamilton-Boone county ...

.

* ''Newspaper Reader'', at the entrance to Steinman Park, Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

* ''

* ''Newspaper Reader'', at the entrance to Steinman Park, Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

* ''Forever Marilyn

''Forever Marilyn'' is a giant statue of Marilyn Monroe designed by Seward Johnson. The statue is a representation of one of the most famous images of Monroe, taken from Billy Wilder's 1955 film ''The Seven Year Itch''. Created in 2011, the sta ...

'' (2011), a , 17-ton representation of Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe (; born Norma Jeane Mortenson; 1 June 1926 4 August 1962) was an American actress. Famous for playing comedic " blonde bombshell" characters, she became one of the most popular sex symbols of the 1950s and early 1960s, as wel ...

standing over a gusty subway grate in her appearance in ''The Seven Year Itch

''The Seven Year Itch'' is a 1955 American romantic comedy film directed by Billy Wilder, from a screenplay he co-wrote with George Axelrod from the 1952 three-act play. The film stars Marilyn Monroe and Tom Ewell, who reprised his stage role. ...

''. Until 2012, the statue was located at Pioneer Court in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, where it attracted many visitors and some controversy for its risque features. It was moved to downtown Palm Springs, California

Palm Springs (Cahuilla: ''Séc-he'') is a desert resort city in Riverside County, California, United States, within the Colorado Desert's Coachella Valley. The city covers approximately , making it the largest city in Riverside County by land a ...

in 2012. In July 2013 plans were announced that it would be moved to New Jersey for a 2014 exhibit honoring Johnson at the Grounds For Sculpture

Grounds For Sculpture (GFS) is a sculpture park and museum located in Hamilton, New Jersey. It is located on the former site of Trenton Speedway. Founded in 1992 by John Seward Johnson II, the venue is dedicated to promoting an understanding of ...

.

*  ''Magic Fountain'' stands outside

''Magic Fountain'' stands outside The Bristol-Myers Squibb Children's Hospital

The Bristol-Myers Squibb Children's Hospital at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital (BMSCH) is a freestanding, 105-bed pediatric acute care children's hospital adjacent to RWJUH. It is affiliated with both Robert Wood Johnson Medical School ...

in New Brunswick, New Jersey

New Brunswick is a city (New Jersey), city in and the county seat, seat of government of Middlesex County, New Jersey, Middlesex County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. many of which are very large, a computer program is employed that translates two-dimensional images into statues that are constructed by a machine driven by the program. Often, these subjects are images that already are well known as the works of others, generating heated ethical controversies regarding

Johnson Atelier Technical Institute of Sculpture

* ttp://siris-artinventories.si.edu/ipac20/ipac.jsp?uri=full=3100001~!316427!0 Art Inventories Catalog {{DEFAULTSORT:Johnson, John Seward 2 Modern artists John Seward II 1930 births 2020 deaths Sculptors from New Jersey United States Navy personnel of the Korean War 20th-century American sculptors 20th-century male artists American male sculptors 21st-century sculptors Trompe-l'œil artists Johnson & Johnson people Schuyler family Military personnel from New Jersey Artists from New Brunswick, New Jersey People from Princeton, New Jersey University of Maine alumni

copyright infringement

Copyright infringement (at times referred to as piracy) is the use of works protected by copyright without permission for a usage where such permission is required, thereby infringing certain exclusive rights granted to the copyright holder, s ...

and derivative works

In copyright law

A copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work, usually for a limited time. The creative work may be in a litera ...

due to substantial similarity issues.

Johnson's works were selected by the United States Information Agency

The United States Information Agency (USIA), which operated from 1953 to 1999, was a United States agency devoted to "public diplomacy". In 1999, prior to the reorganization of intelligence agencies by President George W. Bush, President Bill C ...

to represent the freedoms of the United States in a public and private partnership enterprise representation sponsored by General Motors

The General Motors Company (GM) is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. It is the largest automaker in the United States and ...

and many other US corporations at the World EXPO

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition or an expo, is a large international exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specif ...

celebration in Seville, Spain

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

during 1992.

Criticism

Johnson's work was labeled as "kitsch

Kitsch ( ; loanword from German) is a term applied to art and design that is perceived as naïve imitation, overly-eccentric, gratuitous, or of banal taste.

The avant-garde opposed kitsch as melodramatic and superficial affiliation with ...

" in a 1984 article by an art professor and critic at Princeton University, who explained its rejection as he was commenting on a controversy raging about the work in New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,02 ...

.

His 2003 show at the Corcoran Gallery of Art

The Corcoran Gallery of Art was an art museum in Washington, D.C., United States, that is now the location of the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design, a part of the George Washington University.

Overview

The Corcoran School of the Arts & Design ...

, ''Beyond the Frame: Impressionism Revisited'', which presented his statues imitating famous Impressionist

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage ...

paintings, was a success with audiences, but was panned nationally by acknowledged art critics such as Blake Gopnik

Blake Gopnik (born 1963 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) is an American art critic who has lived in New York City since 2011. He previously spent a decade as chief art critic of ''The Washington Post'', prior to which he was an arts editor and criti ...

writing for ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' and drew strong criticism from curators at other museums about a prominent museum of fine art

In European academic traditions, fine art is developed primarily for aesthetics or creative expression, distinguishing it from decorative art or applied art, which also has to serve some practical function, such as pottery or most metalwork ...

presenting an exhibit of his work.

Philanthropy

Johnson was the chairman and CEO of The Atlantic Foundation, the foundation created by his father, John Seward Johnson I, in 1963. Johnson created the Johnson Atelier Technical Institute of Sculpture, an educational, nonprofit casting and fabrication facility in 1974 as a means of fostering young sculptors' talents, while creating a foundry designed to construct his statues that is so well-equipped and staffed that it is chosen by many renowned sculptors. Educational programs at the Atelier ceased in 2004. The Johnson Atelier now operates as a division of The Sculpture Foundation. Johnson continued to make his sculpture at the facility but casting often was performed off premises, with some of his larger works being cast in thePeople's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

.

He also founded an organization named "The Sculpture Foundation", to promote his works. In 1987, he published ''Celebrating the Familiar: The Sculpture of J. Seward Johnson, Jr''.

Under Johnson's direction, The Atlantic Foundation purchased the old New Jersey Fairgrounds in Hamilton, New Jersey and in 1992 founded the Grounds For Sculpture

Grounds For Sculpture (GFS) is a sculpture park and museum located in Hamilton, New Jersey. It is located on the former site of Trenton Speedway. Founded in 1992 by John Seward Johnson II, the venue is dedicated to promoting an understanding of ...

to display work completed at the Johnson Atelier and other outdoor exhibitions. In 2000 park operations were transferred to a new public charity with the same intent that continues to operate the park.

He was president of the International Sculpture Center

The International Sculpture Center is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization founded in 1960 by Elden Tefft and James A. Sterritt at the University of Kansas. It is currently located on the old New Jersey Fairground in Hamilton, New Jersey

Its goal is ...

of Hamilton, New Jersey, which publishes a magazine out of offices in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

Johnson also was the president of a large oceanographic research institution in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

that had been founded by his father. The institution published a science magazine.

Johnson and his wife funded the construction of The Joyce and Seward Johnson Theater for the Theater for the New City

Theater for the New City, founded in 1971 and known familiarly as "TNC", is one of New York City's leading off-off-Broadway theaters, known for radical political plays and community commitment. Productions at TNC have won 43 Obie Awards and the P ...

, an Off-Broadway

An off-Broadway theatre is any professional theatre venue in New York City with a seating capacity between 100 and 499, inclusive. These theatres are smaller than Broadway theatres, but larger than off-off-Broadway theatres, which seat fewer tha ...

theater in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.

Personal life

Johnson was excluded from his father's will, which left the bulk of his fortune toBarbara Piasecka Johnson

Barbara "Basia" Piasecka Johnson (born Barbara Piasecka; February 25, 1937 – April 1, 2013) was a Polish humanitarian, philanthropist, art connoisseur and collector.

Early life

Piasecka Johnson was born in Staniewicze near Grodno, Poland (n ...

, his father's wife and former chambermaid. He and his siblings sued on grounds that their father was not mentally competent at the time he signed the will. It was settled out of court, and the children were granted about 12% of the fortune.

Johnson was formerly married to Barbara Kline. She often engaged in extramarital affairs in their home, driving Johnson to attempt suicide. In 1965, he acknowledged paternity to Jenia Anne "Cookie" Johnson to speed up the divorce process. Years later, Johnson's family had a legal battle regarding Cookie Johnson's eligibility for a share in the Johnson & Johnson fortune. The court ruled in favor of Cookie.

Johnson later married Joyce Horton, a novelist. They had two children, John Seward Johnson III

John Seward Johnson III (born September 2, 1966) is an American filmmaker, philanthropist and entrepreneur. He is a great-grandson of Robert Wood Johnson I (co-founder of Johnson & Johnson) and the son of artist John Seward Johnson II.

He is the ...

and actress Clelia Constance Johnson, who is credited as "India Blake."

Johnson died from cancer at his home in Key West, Florida

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Sigsbee Park, Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Isla ...

on March 10, 2020, at the age of 89.

See also

* '' The Newspaper Reader'' (1978), Forest Grove, Oregon, U.S. * ''Rogers v. Koons

''Rogers v. Koons'', 960 F.2d 301 (2d Cir. 1992), is a leading U.S. court case on copyright, dealing with the fair use defense for parody. The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit found that an artist copying a photograph could ...

''

References

Further reading

* * * *External links

*Johnson Atelier Technical Institute of Sculpture

* ttp://siris-artinventories.si.edu/ipac20/ipac.jsp?uri=full=3100001~!316427!0 Art Inventories Catalog {{DEFAULTSORT:Johnson, John Seward 2 Modern artists John Seward II 1930 births 2020 deaths Sculptors from New Jersey United States Navy personnel of the Korean War 20th-century American sculptors 20th-century male artists American male sculptors 21st-century sculptors Trompe-l'œil artists Johnson & Johnson people Schuyler family Military personnel from New Jersey Artists from New Brunswick, New Jersey People from Princeton, New Jersey University of Maine alumni