John Pizer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A series of murders that took place in the

A series of murders that took place in the

Montague John Druitt (15 August 1857 – early December 1888) was a

Montague John Druitt (15 August 1857 – early December 1888) was a

Seweryn Antonowicz Kłosowski (alias George Chapman; no relation to victim

Seweryn Antonowicz Kłosowski (alias George Chapman; no relation to victim

John Pizer or Piser (c. 1850–1897) was a Polish Jew who worked as a bootmaker in Whitechapel. In the early days of the Whitechapel murders, many locals suspected that "Leather Apron" was the killer, which was picked up by the press, and Pizer was known as "Leather Apron". He had a prior conviction for a stabbing offence, and Police Sergeant William Thicke apparently believed that he had committed a string of minor assaults on prostitutes.Marriott, p. 251 After the murders of

John Pizer or Piser (c. 1850–1897) was a Polish Jew who worked as a bootmaker in Whitechapel. In the early days of the Whitechapel murders, many locals suspected that "Leather Apron" was the killer, which was picked up by the press, and Pizer was known as "Leather Apron". He had a prior conviction for a stabbing offence, and Police Sergeant William Thicke apparently believed that he had committed a string of minor assaults on prostitutes.Marriott, p. 251 After the murders of

Francis Tumblety (c. 1833–1903) earned a small fortune posing as an "Indian Herb" doctor throughout the United States and Canada, and was commonly perceived as a

Francis Tumblety (c. 1833–1903) earned a small fortune posing as an "Indian Herb" doctor throughout the United States and Canada, and was commonly perceived as a

William Henry Bury (25 May 1859 – 24 April 1889) had recently moved to

William Henry Bury (25 May 1859 – 24 April 1889) had recently moved to

Dr. Thomas Neill Cream (27 May 1850 – 15 November 1892) was a doctor secretly specialising in abortions. He was born in

Dr. Thomas Neill Cream (27 May 1850 – 15 November 1892) was a doctor secretly specialising in abortions. He was born in

Frederick Bailey Deeming (30 July 1853 – 23 May 1892) murdered his first wife and four children in

Frederick Bailey Deeming (30 July 1853 – 23 May 1892) murdered his first wife and four children in

Robert Donston Stephenson (also known as Roslyn D'Onston; 20 April 1841 – 9 October 1916) was a journalist and writer interested in the

Robert Donston Stephenson (also known as Roslyn D'Onston; 20 April 1841 – 9 October 1916) was a journalist and writer interested in the

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale (8 January 1864 – 14 January 1892) was first mentioned in print as a potential suspect when

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale (8 January 1864 – 14 January 1892) was first mentioned in print as a potential suspect when

Joseph Barnett (c. 1858–1927) was a former fish porter, and victim Mary Kelly's lover from 8 April 1887 to 30 October 1888, when they quarrelled and separated after he lost his job and she returned to prostitution to make a living. Inspector Abberline questioned him for four hours after Kelly's murder, and his clothes were examined for bloodstains, but he was then released without charge. A century after the murders, author Bruce Paley proposed him as a suspect as Kelly's scorned or jealous lover, and suggested that he'd committed the other murders to scare Kelly off the streets and out of prostitution.Rumbelow, p. 262; Whitehead and Rivett, pp. 122–123 Other authors suggest he killed Kelly only, and mutilated the body to make it look like a Ripper murder, but Abberline's investigation appears to have exonerated him. Other acquaintances of Kelly put forward as her murderer include her landlord John McCarthy and her former boyfriend Joseph Fleming.

Joseph Barnett (c. 1858–1927) was a former fish porter, and victim Mary Kelly's lover from 8 April 1887 to 30 October 1888, when they quarrelled and separated after he lost his job and she returned to prostitution to make a living. Inspector Abberline questioned him for four hours after Kelly's murder, and his clothes were examined for bloodstains, but he was then released without charge. A century after the murders, author Bruce Paley proposed him as a suspect as Kelly's scorned or jealous lover, and suggested that he'd committed the other murders to scare Kelly off the streets and out of prostitution.Rumbelow, p. 262; Whitehead and Rivett, pp. 122–123 Other authors suggest he killed Kelly only, and mutilated the body to make it look like a Ripper murder, but Abberline's investigation appears to have exonerated him. Other acquaintances of Kelly put forward as her murderer include her landlord John McCarthy and her former boyfriend Joseph Fleming.

Lewis Carroll (

Lewis Carroll (

William Berry "Willy" Clarkson (1861 – 12 October 1934) was the royal wigmaker and costume-maker to Queen Victoria and lived approximately two miles from each of the canonical five crime scenes. He was first named as a suspect in 2019, with many of the assertions based on Clarkson's 1937 biography written by Harry J. Greenwall. Clarkson is known to have stalked his ex-fiancée and was reputedly a blackmailer and arsonist. He is suspected of committing the murders to cover up his blackmail schemes. Evidence presented to support the theory of Clarkson as a suspect included the revelation that he admitted one of his custom-made wigs was found near the scene of one of the Ripper killings, a fact not previously widely known in the Ripperology community. Additionally, Clarkson's biography quotes him as stating that the police obtained disguises from him for their search for the Ripper, and as such, he would have been aware of the trails they followed, allowing him to elude capture. Hair-cutting shears and barber-surgeon tools (his father or grandfather allegedly being a barber-surgeon) of the kind used by a wig-maker at the time closely match the shape and style of the weapons suspected to have been used in the murders.

William Berry "Willy" Clarkson (1861 – 12 October 1934) was the royal wigmaker and costume-maker to Queen Victoria and lived approximately two miles from each of the canonical five crime scenes. He was first named as a suspect in 2019, with many of the assertions based on Clarkson's 1937 biography written by Harry J. Greenwall. Clarkson is known to have stalked his ex-fiancée and was reputedly a blackmailer and arsonist. He is suspected of committing the murders to cover up his blackmail schemes. Evidence presented to support the theory of Clarkson as a suspect included the revelation that he admitted one of his custom-made wigs was found near the scene of one of the Ripper killings, a fact not previously widely known in the Ripperology community. Additionally, Clarkson's biography quotes him as stating that the police obtained disguises from him for their search for the Ripper, and as such, he would have been aware of the trails they followed, allowing him to elude capture. Hair-cutting shears and barber-surgeon tools (his father or grandfather allegedly being a barber-surgeon) of the kind used by a wig-maker at the time closely match the shape and style of the weapons suspected to have been used in the murders.

Sir William Withey Gull, Bt (31 December 1816 – 29 January 1890) was physician-in-ordinary to

Sir William Withey Gull, Bt (31 December 1816 – 29 January 1890) was physician-in-ordinary to

James Kelly (20 April 1860 – 17 September 1929; no relation to victim Mary Kelly) was first identified as a suspect in Terence Sharkey's ''Jack the Ripper. 100 Years of Investigation'' (Ward Lock 1987) and documented in ''Prisoner 1167: The madman who was Jack the Ripper'', by Jim Tully, in 1997.

James Kelly murdered his wife in 1883 by stabbing her in the neck. Deemed insane, he was committed to the

James Kelly (20 April 1860 – 17 September 1929; no relation to victim Mary Kelly) was first identified as a suspect in Terence Sharkey's ''Jack the Ripper. 100 Years of Investigation'' (Ward Lock 1987) and documented in ''Prisoner 1167: The madman who was Jack the Ripper'', by Jim Tully, in 1997.

James Kelly murdered his wife in 1883 by stabbing her in the neck. Deemed insane, he was committed to the

Charles Allen Lechmere (5 October 1849 – 23 December 1920), also known as Charles Cross, was a meat cart driver for the Pickfords company, and is conventionally regarded as an innocent witness who discovered the body of the first canonical Ripper victim,

Charles Allen Lechmere (5 October 1849 – 23 December 1920), also known as Charles Cross, was a meat cart driver for the Pickfords company, and is conventionally regarded as an innocent witness who discovered the body of the first canonical Ripper victim,

James Maybrick (24 October 1838 – 11 May 1889) was a

James Maybrick (24 October 1838 – 11 May 1889) was a

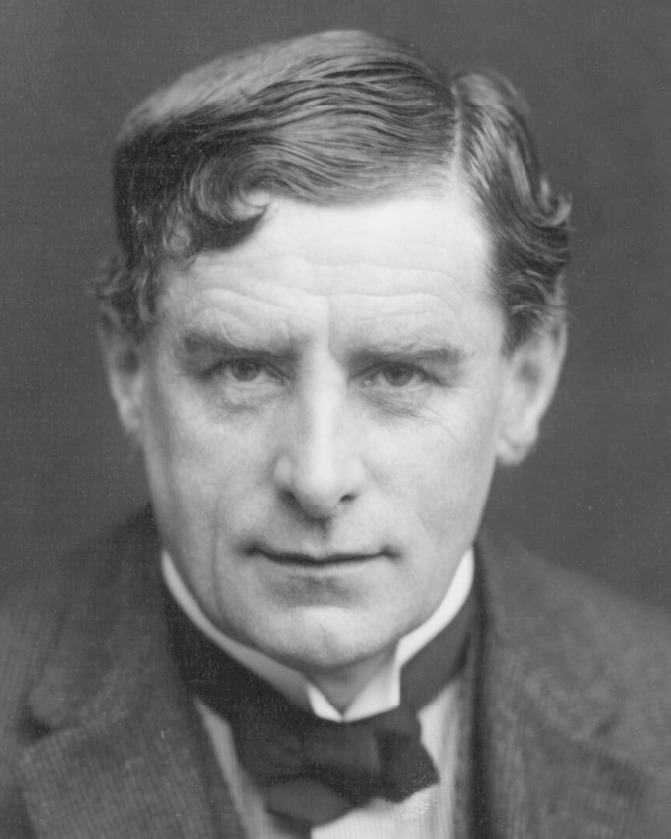

Walter Richard Sickert (31 May 1860 – 22 January 1942) was a German-born artist of British and Danish ancestry, who was first mentioned as a possible Ripper suspect in

Walter Richard Sickert (31 May 1860 – 22 January 1942) was a German-born artist of British and Danish ancestry, who was first mentioned as a possible Ripper suspect in

"Sickert, Walter Richard (1860–1942)"

''

James Kenneth Stephen (25 February 1859 – 3 February 1892) was first suggested as a suspect in a biography of another Ripper suspect,

James Kenneth Stephen (25 February 1859 – 3 February 1892) was first suggested as a suspect in a biography of another Ripper suspect,

Sir John Williams, Bt (6 November 1840 – 24 May 1926) was obstetrician to Queen Victoria's daughter

Sir John Williams, Bt (6 November 1840 – 24 May 1926) was obstetrician to Queen Victoria's daughter

Casebook: Jack the Ripper

*

Jack the Ripper suspects

{{Jack the Ripper Suspects

A series of murders that took place in the

A series of murders that took place in the East End of London

The East End of London, often referred to within the London area simply as the East End, is the historic core of wider East London, east of the Roman and medieval walls of the City of London and north of the River Thames. It does not have uni ...

from August to November 1888 was blamed on an unidentified assailant who was nicknamed Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in the autumn of 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer wa ...

. Since that time, the identity of the killer or killers has been widely debated, and over 100 suspects have been named. Though many theories have been advanced, experts find none widely persuasive, and some are hardly taken seriously at all. Due to the extensive time interval since the murders, the killer will likely never be identified despite ongoing speculation as to his identity.

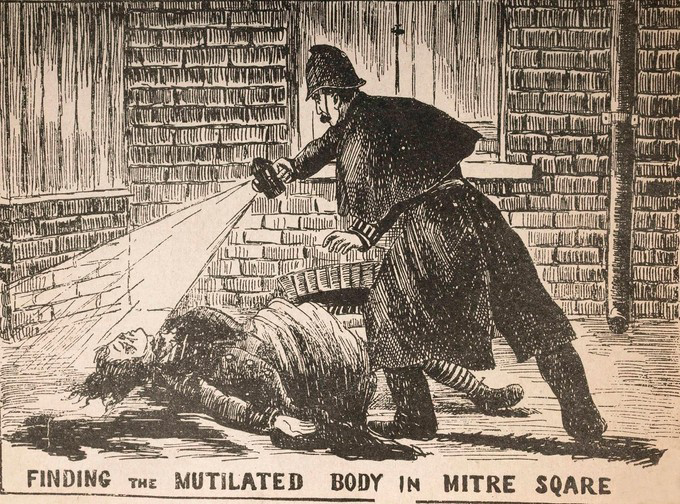

Contemporaneous police opinion

Metropolitan Police

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

files show that their investigation into the serial killings encompassed 11 separate murders between 1888 and 1891, known in the police docket as the "Whitechapel murders

The Whitechapel murders were committed in or near the largely impoverished Whitechapel district in the East End of London between 3 April 1888 and 13 February 1891. At various points some or all of these eleven unsolved murders of women have ...

". Five of these—the murders of Mary Ann Nichols

Mary Ann Nichols, known as Polly Nichols (née Walker; 26 August 184531 August 1888), was the first canonical victim of the unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, who is believed to have murdered and mutilated at least five women i ...

, Annie Chapman

Annie Chapman (born Eliza Ann Smith; 25 September 1840 – 8 September 1888) was the second Jack the Ripper#Canonical five, canonical victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilation, mutilated a min ...

, Elizabeth Stride

Elizabeth "Long Liz" Stride ( Gustafsdotter; 27 November 1843 – 30 September 1888) is believed to have been the third victim of the unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated at least five women in the Whitecha ...

, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly

Mary Jane Kelly ( – 9 November 1888), also known as Marie Jeanette Kelly, Fair Emma, Ginger, Dark Mary and Black Mary, is widely believed to have been the final victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who murdered ...

—are generally agreed to be the work of a single killer, known as "Jack the Ripper". These murders occurred between August and November 1888 within a short distance of each other, and are collectively known as the " canonical five". The six other murders—those of Emma Elizabeth Smith

Emma Elizabeth Smith ( 1843 – 4 April 1888) was a prostitute and murder victim of mysterious origins in late-19th century London. Her killing was the first of the Whitechapel murders, and it is possible she was a victim of the serial killer kno ...

, Martha Tabram

Martha Tabram (née White; 10 May 1849 – 7 August 1888) was an English woman killed in a spate of violent murders in and around the Whitechapel district of East London between 1888 and 1891. She may have been the first victim of the still-uni ...

, Rose Mylett, Alice McKenzie, Frances Coles, and the Pinchin Street torso—have been linked with Jack the Ripper to varying degrees.

The swiftness of the attacks, and the manner of the mutilations performed on some of the bodies, which included disembowelment and removal of organs, led to speculation that the murderer had the skills of a physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

or butcher. However, others disagreed strongly, and thought the wounds too crude to be professional. The alibis of local butchers and slaughterers were investigated, with the result that they were eliminated from the inquiry. Over 2,000 people were interviewed, "upwards of 300" people were investigated, and 80 people were detained.

During the course of their investigations of the murders, police regarded several men as strong suspects, though none were ever formally charged.

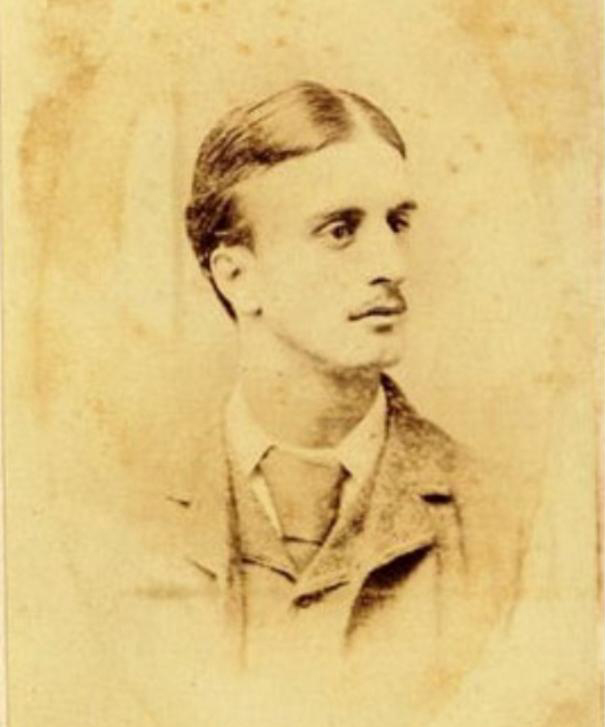

Montague John Druitt

Montague John Druitt (15 August 1857 – early December 1888) was a

Montague John Druitt (15 August 1857 – early December 1888) was a Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset (unitary authority), Dors ...

-born barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

who worked to supplement his income as an assistant schoolmaster in Blackheath, London

Blackheath is an area in Southeast London, straddling the border of the Royal Borough of Greenwich and the London Borough of Lewisham. It is located northeast of Lewisham, south of Greenwich and southeast of Charing Cross, the traditional ce ...

, until his dismissal shortly before his suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

by drowning in 1888.Rumbelow, p. 155 His decomposed body was found floating in the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

near Chiswick

Chiswick ( ) is a district of west London, England. It contains Hogarth's House, the former residence of the 18th-century English artist William Hogarth; Chiswick House, a neo-Palladian villa regarded as one of the finest in England; and Full ...

on 31 December 1888. Some modern authors suggest that Druitt may have been dismissed because he was homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

and that this could have driven him to commit suicide. However, both his mother and his grandmother suffered mental health

Mental health encompasses emotional, psychological, and social well-being, influencing cognition, perception, and behavior. It likewise determines how an individual handles stress, interpersonal relationships, and decision-making. Mental health ...

problems, and it is possible that he was dismissed because of an underlying hereditary psychiatric illness. His death shortly after the last canonical murder (which took place on 9 November 1888) led Assistant Chief Constable Sir Melville Macnaghten

Sir Melville Leslie Macnaghten (16 June 1853, Woodford, London −12 May 1921) was Assistant Commissioner (Crime) of the London Metropolitan Police from 1903 to 1913. A highly regarded and famously affable figure of the late Victorian and Edw ...

to name him as a suspect in a memorandum of 23 February 1894. However, Macnaghten incorrectly described the 31-year-old barrister as a 41-year-old doctor. On 1 September, the day after the first canonical murder, Druitt was in Dorset playing cricket, and most experts now believe that the killer was local to Whitechapel, whereas Druitt lived miles away on the other side of the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. Inspector Frederick Abberline

Frederick George Abberline (8 January 1843 – 10 December 1929) was a British chief inspector for the London Metropolitan Police. He is best known for being a prominent police figure in the investigation into the Jack the Ripper serial killer ...

appeared to dismiss Druitt as a serious suspect on the basis that the only evidence against him was the coincidental timing of his suicide shortly after the last canonical murder.

Seweryn Kłosowski

Seweryn Antonowicz Kłosowski (alias George Chapman; no relation to victim

Seweryn Antonowicz Kłosowski (alias George Chapman; no relation to victim Annie Chapman

Annie Chapman (born Eliza Ann Smith; 25 September 1840 – 8 September 1888) was the second Jack the Ripper#Canonical five, canonical victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilation, mutilated a min ...

; 14 December 1865 – 7 April 1903) was born in Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

, but emigrated to the United Kingdom sometime between 1887 and 1888, shortly before the start of the Whitechapel murders. Between 1893 and 1894 he assumed the name of Chapman. He successively poisoned three of his wives and became known as "the borough poisoner". He was hanged for his crimes in 1903. At the time of the Ripper murders, he lived in Whitechapel, London, where he had been working as a barber under the name Ludwig Schloski. According to H. L. Adam, who wrote a book on the poisonings in 1930, Chapman was Inspector Frederick Abberline

Frederick George Abberline (8 January 1843 – 10 December 1929) was a British chief inspector for the London Metropolitan Police. He is best known for being a prominent police figure in the investigation into the Jack the Ripper serial killer ...

's favoured suspect, and the ''Pall Mall Gazette

''The Pall Mall Gazette'' was an evening newspaper founded in London on 7 February 1865 by George Murray Smith; its first editor was Frederick Greenwood. In 1921, '' The Globe'' merged into ''The Pall Mall Gazette'', which itself was absorbed int ...

'' reported that Abberline suspected Chapman after his conviction. However, others disagree that Chapman is a likely culprit, as he murdered his three wives with poison, and it is uncommon (though not unheard of) for a serial killer to make such a drastic change in ''modus operandi

A ''modus operandi'' (often shortened to M.O.) is someone's habits of working, particularly in the context of business or criminal investigations, but also more generally. It is a Latin phrase, approximately translated as "mode (or manner) of op ...

''.

Aaron Kosminski

Aaron Kosminski (born Aron Mordke Kozminski; 11 September 1865 – 24 March 1919) was aPolish Jew

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the lon ...

who was admitted to Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum in 1891. "Kosminski" (without a forename) was named as a suspect by Sir Melville Macnaghten

Sir Melville Leslie Macnaghten (16 June 1853, Woodford, London −12 May 1921) was Assistant Commissioner (Crime) of the London Metropolitan Police from 1903 to 1913. A highly regarded and famously affable figure of the late Victorian and Edw ...

in his 1894 memorandum and by former Chief Inspector Donald Swanson

Chief Inspector Donald Sutherland Swanson (12 August 1848 - 24 November 1924) was born at Geise, where his father operated a distillery, before the family moved in 1851 to Thurso, and was a senior police officer in the Metropolitan Police in Lond ...

in handwritten comments in the margin of his copy of Assistant Commissioner Sir Robert Anderson's memoirs.

Anderson wrote that “the only person who had ever had a good view of the murderer unhesitatingly identified the suspect the instant he was confronted with him”. This suspect also apparently fit their profile: “a sexual maniac of a virulent type; that he was living in the immediate vicinity of the scenes of the murders; and that, if he was not living immediately alone, his people knew of his guilt, and refused to give him up to justice”. Furthermore a “house-to-house search was conducted” for “the case of every man in the district whose circumstances were such that he could go and come and get rid of his bloodstains in secret.” Sir Robert Anderson goes on to state the conclusion the police came to following this investigation “was that he ack the Ripperand his people were certain low-class Polish Jews”. But since the person who identified him was also a Polish Jew and “people of that class in the East End will not give up one of their number to Gentile Justice” the suspect was never prosecuted. Anderson was firmly convinced of the suspect’s guilt, also writing within “The Whitechapel Murders” section of his memoirs is that “‘undiscovered murders’ are rare in London and the ‘Jack-the-Ripper’ crimes are not within that category”. Some authors are sceptical of this, while others use it in their theories.

In his memorandum, Macnaghten stated that no one was ever identified as the Ripper, which directly contradicts Anderson's recollection. In 1987, author Martin Fido

Martin Austin Fido (18 October 1939 – 2 April 2019) was a university professor, true crime writer and broadcaster. His many books include ''The Crimes, Detection and Death of Jack the Ripper'', ''The Official Encyclopedia of Scotland Yard'', ' ...

searched asylum records for any inmates called Kosminski, and found only one: Aaron Kosminski. Kosminski lived in Whitechapel; however, he was largely harmless in the asylum. His insanity took the form of auditory hallucinations, a paranoid fear of being fed by other people, a refusal to wash or bathe, and "self-abuse". In his book '' The Cases That Haunt Us'', former FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and its principal Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement age ...

profiler John Douglas states that a paranoid

Paranoia is an instinct or thought process that is believed to be heavily influenced by anxiety or fear, often to the point of delusion and irrationality. Paranoid thinking typically includes persecutory beliefs, or beliefs of conspiracy c ...

individual such as Kosminski would likely have openly boasted of the murders while incarcerated had he been the killer, but there is no record that he ever did so.

In 2014, DNA analysis tenuously linked Kosminski with a shawl said to have belonged to victim Catherine Eddowes, but experts – including Professor Sir Alec Jeffreys

Sir Alec John Jeffreys, (born 9 January 1950) is a British geneticist known for developing techniques for genetic fingerprinting and DNA profiling which are now used worldwide in forensic science to assist police detective work and to resolv ...

, the inventor of genetic fingerprinting

DNA profiling (also called DNA fingerprinting) is the process of determining an individual's DNA characteristics. DNA analysis intended to identify a species, rather than an individual, is called DNA barcoding.

DNA profiling is a forensic tec ...

– dismissed the claims as unreliable. This was because the genetic match, determined from maternal descendants of Eddowes and Kosminski, was based on mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

; strands of mitochondrial DNA can be shared by thousands of people, and therefore can only be reliably used in crime analysis to exclude a suspect, not to implicate them. Furthermore, many consider it conjecture without substantial evidence that the shawl, purportedly removed from the crime scene by police constable Amos Simpson, even belonged to Eddowes – who herself was impoverished, and arguably could not have afforded to purchase it herself. In March 2019, the ''Journal of Forensic Sciences

The ''Journal of Forensic Sciences'' (''JFS'') is a bimonthly peer-reviewed scientific journal is the official publication of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, published by Wiley-Blackwell. It covers all aspects of forensic science. The mi ...

'' published a study that claimed DNA from Kosminski and Catherine Eddowes was found on the shawl, though other scientists have cast doubt on the study. A BBC documentary ''Jack the Ripper: The Case Reopened'', broadcast the same year and presented by Emilia Fox

Emilia Rose Elizabeth Fox (born 31 July 1974) is an English actress and presenter whose film debut was in Roman Polanski's film '' The Pianist''. Her other films include the Italian–French–British romance-drama film '' The Soul Keeper'' (2 ...

, concluded that Kosminski was the most likely suspect.

Michael Ostrog

Michael Ostrog (c. 1833–in or after 1904) was aRussia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

n-born professional con man

A confidence trick is an attempt to defraud a person or group after first gaining their trust. Confidence tricks exploit victims using their credulity, naïveté, compassion, vanity, confidence, irresponsibility, and greed. Researchers have def ...

and thief.

He used numerous aliases and assumed titles. Among his many dubious claims was that he had once been a surgeon in the Russian Navy. He was mentioned as a suspect by Macnaghten, who joined the case in 1889, the year after the "canonical five" victims were killed. Researchers have failed to find evidence that he had committed crimes any more serious than fraud and theft. Author Philip Sugden discovered prison records showing that Ostrog was jailed for petty offences in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

during the Ripper murders. Ostrog was last mentioned alive in 1904; the date of his death is unknown.

John Pizer

John Pizer or Piser (c. 1850–1897) was a Polish Jew who worked as a bootmaker in Whitechapel. In the early days of the Whitechapel murders, many locals suspected that "Leather Apron" was the killer, which was picked up by the press, and Pizer was known as "Leather Apron". He had a prior conviction for a stabbing offence, and Police Sergeant William Thicke apparently believed that he had committed a string of minor assaults on prostitutes.Marriott, p. 251 After the murders of

John Pizer or Piser (c. 1850–1897) was a Polish Jew who worked as a bootmaker in Whitechapel. In the early days of the Whitechapel murders, many locals suspected that "Leather Apron" was the killer, which was picked up by the press, and Pizer was known as "Leather Apron". He had a prior conviction for a stabbing offence, and Police Sergeant William Thicke apparently believed that he had committed a string of minor assaults on prostitutes.Marriott, p. 251 After the murders of Mary Ann Nichols

Mary Ann Nichols, known as Polly Nichols (née Walker; 26 August 184531 August 1888), was the first canonical victim of the unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, who is believed to have murdered and mutilated at least five women i ...

and Annie Chapman

Annie Chapman (born Eliza Ann Smith; 25 September 1840 – 8 September 1888) was the second Jack the Ripper#Canonical five, canonical victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilation, mutilated a min ...

in late August and early September 1888 respectively, Thicke arrested Pizer on 10 September, even though the investigating inspector reported that "there is no evidence whatsoever against him". He was cleared of suspicion when it turned out that he had alibis for two of the murders. He was staying with relatives at the time of one of the murders, and he was talking with a police officer while watching a spectacular fire on the London Docks

London Docklands is the riverfront and former docks in London. It is located in inner east and southeast London, in the boroughs of Southwark, Tower Hamlets, Lewisham, Newham, and Greenwich. The docks were formerly part of the Port of L ...

at the time of another. Pizer and Thicke had known each other for years, and Pizer implied that his arrest was based on animosity rather than evidence. Pizer successfully obtained monetary compensation from at least one newspaper that had named him as the murderer. Thicke himself was accused of being the Ripper by H. T. Haslewood of Tottenham

Tottenham () is a town in North London, England, within the London Borough of Haringey. It is located in the ceremonial county of Greater London. Tottenham is centred north-northeast of Charing Cross, bordering Edmonton to the north, Waltham ...

in a letter to the Home Office dated 10 September 1889; the presumably malicious accusation was dismissed as without foundation.

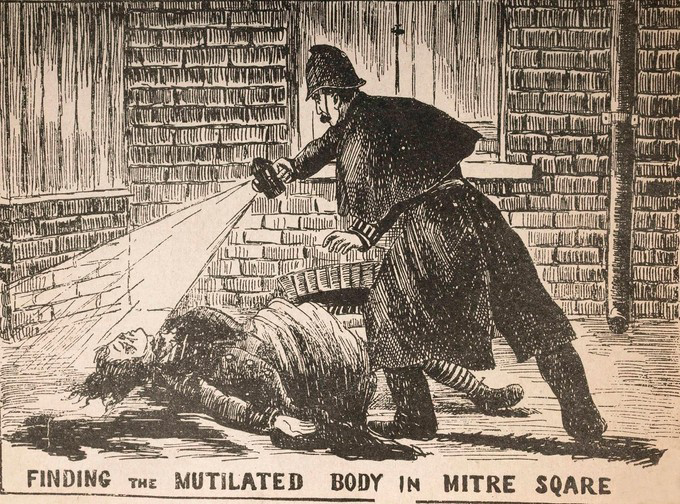

James Thomas Sadler

James Thomas Sadler or Saddler (c. 1837 – 1906 or 1910) was a friend of Frances Coles, the last victim added to theWhitechapel murders

The Whitechapel murders were committed in or near the largely impoverished Whitechapel district in the East End of London between 3 April 1888 and 13 February 1891. At various points some or all of these eleven unsolved murders of women have ...

police file. Coles was murdered on 13 February 1891. Her body was discovered beneath a railway arch in Swallow Gardens, Whitechapel. Two deep slash wounds had been inflicted to her neck. She was still alive but died before medical help could arrive. Sadler was arrested, but little evidence existed against him. Though briefly considered by the police as a Ripper suspect, he was at sea at the time of the first four "canonical" murders, and was released without charge. Sadler was named in Macnaghten's 1894 memorandum in connection with Coles's murder. Macnaghten thought Sadler "was a man of ungovernable temper and entirely addicted to drink, and the company of the lowest prostitutes".

Francis Tumblety

Francis Tumblety (c. 1833–1903) earned a small fortune posing as an "Indian Herb" doctor throughout the United States and Canada, and was commonly perceived as a

Francis Tumblety (c. 1833–1903) earned a small fortune posing as an "Indian Herb" doctor throughout the United States and Canada, and was commonly perceived as a misogynist

Misogyny () is hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women. It is a form of sexism that is used to keep women at a lower social status than men, thus maintaining the societal roles of patriarchy. Misogyny has been widely practiced f ...

and a quack

Quack, The Quack or Quacks may refer to:

People

* Quack Davis, American baseball player

* Hendrick Peter Godfried Quack (1834–1917), Dutch economist and historian

* Joachim Friedrich Quack (born 1966), German Egyptologist

* Johannes Quack (b ...

. He was connected to the death of one of his patients, but escaped prosecution. In 1865, he was arrested for alleged complicity in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was assassinated by well-known stage actor John Wilkes Booth, while attending the play ''Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Shot in the hea ...

, but no connection was found and he was released without being charged. Tumblety was in England in 1888, and was arrested on 7 November, apparently for engaging in homosexual acts, which were illegal at the time. It was reported by some of his friends that he showed off a collection of "matrices" (wombs) from "every class of woman" at around this time. Awaiting trial, he fled to France and then to the United States. Already notorious in the States for his self-promotion and previous criminal charges, his arrest was reported as connected to the Ripper murders. American reports that Scotland Yard tried to extradite him were not confirmed by the British press or the London police, and the New York City Police

The New York City Police Department (NYPD), officially the City of New York Police Department, established on May 23, 1845, is the primary municipal law enforcement agency within the New York City, City of New York, the largest and one of ...

said, "there is no proof of his complicity in the Whitechapel murders, and the crime for which he is under bond in London is not extraditable". In 1913, Tumblety was mentioned as a Ripper suspect by Chief Inspector John Littlechild

Detective Chief Inspector John George Littlechild (21 December 1848 – 2 January 1923) was the first commander of the London Metropolitan Police Special Irish Branch, renamed Special Branch in 1888.

Littlechild was born in Royston, Her ...

of the Metropolitan Police Service

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

in a letter to journalist and author George R. Sims

George Robert Sims (2 September 1847 – 4 September 1922) was an English journalist, poet, dramatist, novelist and ''bon vivant''.

Sims began writing lively humour and satiric pieces for ''Fun'' magazine and ''The Referee'', but he was soon co ...

.

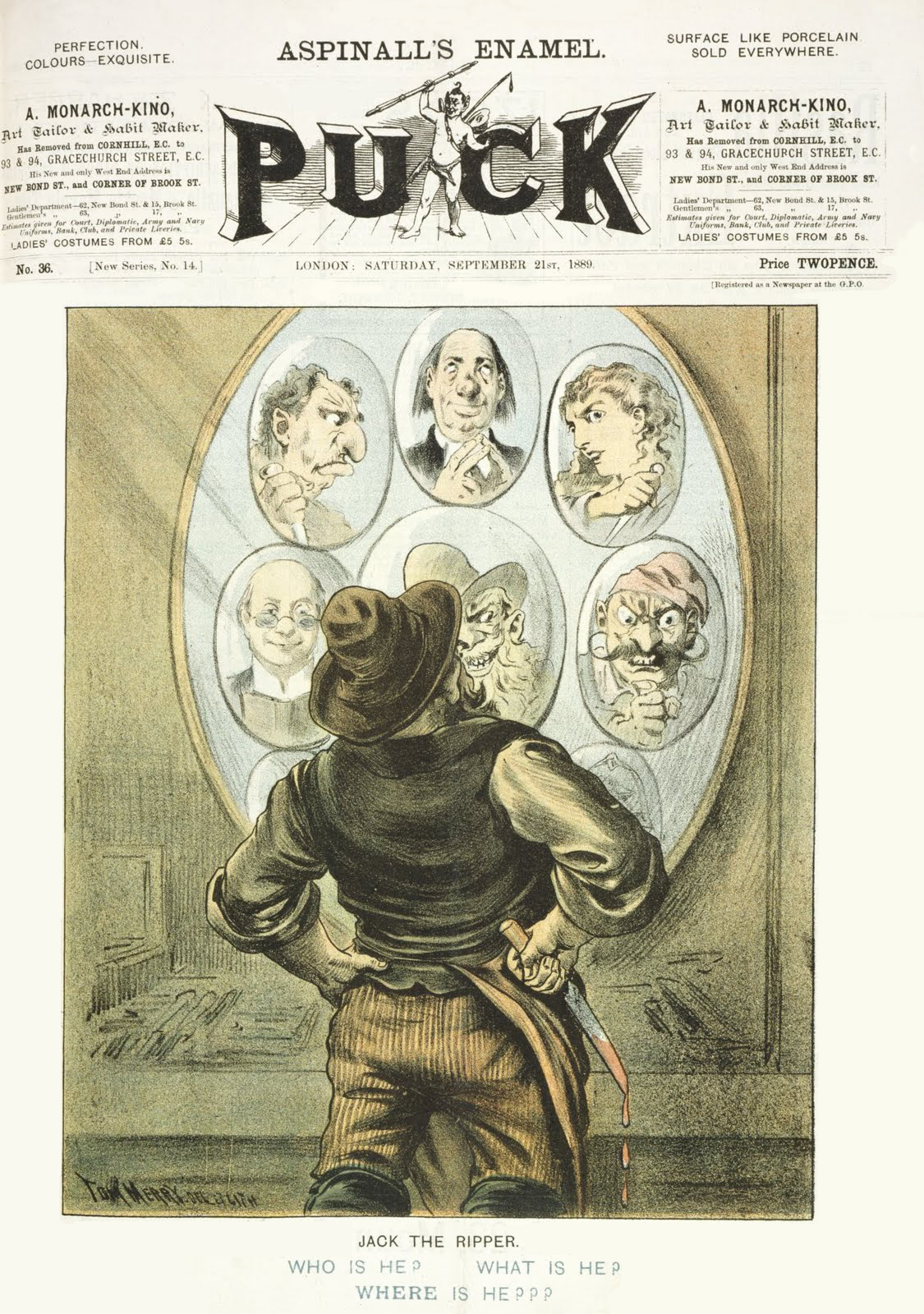

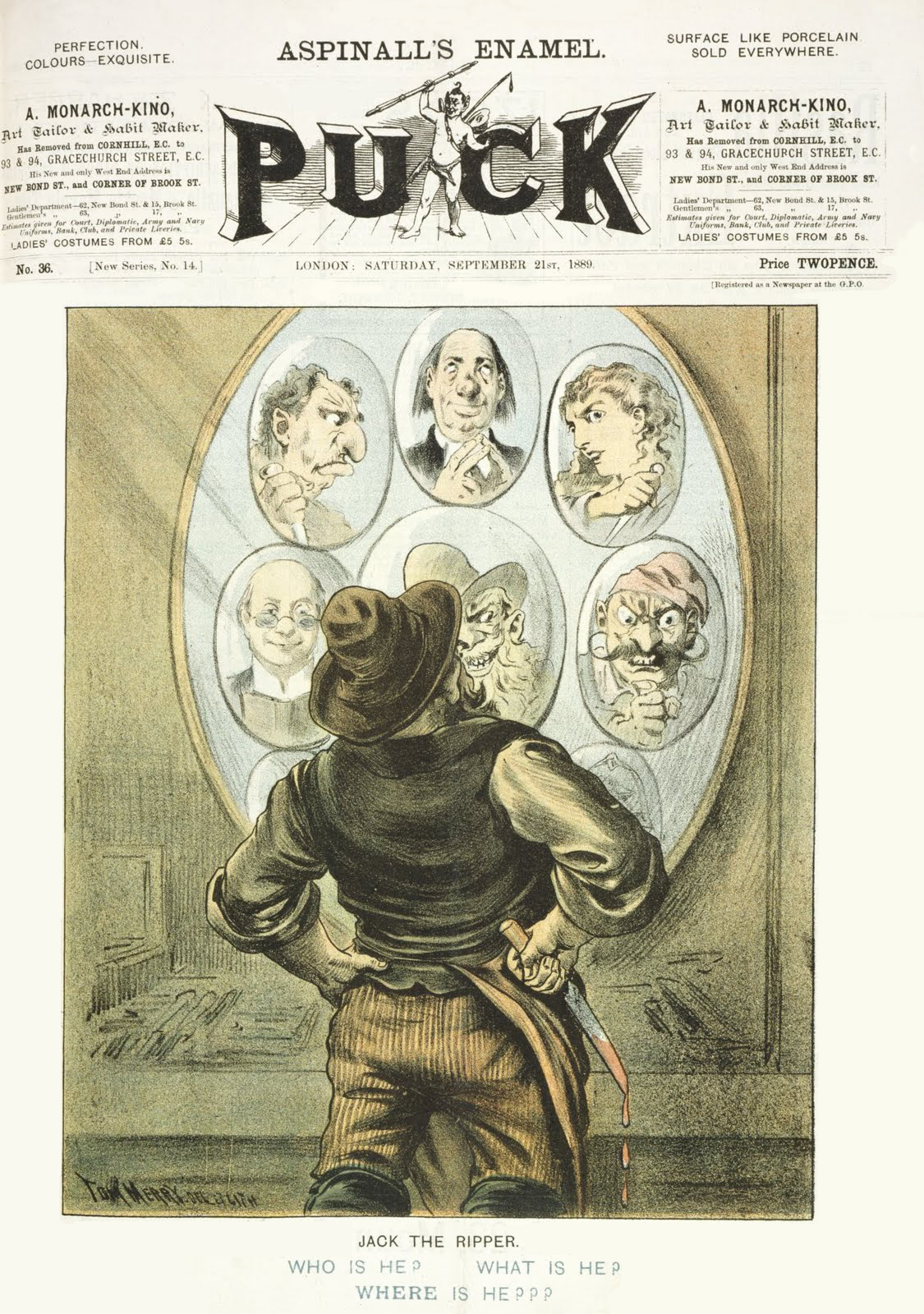

Contemporaneous press and public opinion

The Whitechapel murders were featured heavily in the media and attracted the attention of Victorian society at large. Journalists, letter writers, and amateur detectives all suggested names either in the press or to the police. Most were not and could not be taken seriously. For example, at the time of the murders,Richard Mansfield

Richard Mansfield (24 May 1857 – 30 August 1907) was an English actor-manager best known for his performances in Shakespeare plays, Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and the play '' Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde''.

Life and career

Mansfield was born ...

, a famous actor, starred in a theatrical version of Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll a ...

's book ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'' is a 1886 Gothic novella by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson. It follows Gabriel John Utterson, a London-based legal practitioner who investigates a series of strange occurrences between his old ...

''. The subject matter of horrific murder in the London streets and Mansfield's convincing portrayal led letter writers to accuse him of being the Ripper.

William Henry Bury

William Henry Bury (25 May 1859 – 24 April 1889) had recently moved to

William Henry Bury (25 May 1859 – 24 April 1889) had recently moved to Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

from the East End of London, when he strangled his wife Ellen Elliott, a former prostitute, on 4 February 1889. He inflicted extensive wounds to her abdomen after she was dead and packed the body into a trunk. On 10 February, Bury went to the local police and told them his wife had committed suicide. He was arrested, tried, found guilty of her murder, and hanged in Dundee. A link with the Ripper crimes was investigated by police, but Bury denied any connection, despite making a full confession to his wife's homicide. Nevertheless, the executioner, James Berry, promoted the idea that Bury was the Ripper. This hypothesis was built upon by historians Euan Macpherson and William Beadle, who argued that comments by Ellen had indicated she had inside knowledge of the Ripper's whereabouts. There was also graffiti at Bury's flat accusing the occupant of being "Jack Ripper", which Macpherson argues Bury had written as a form of confession, and the final of the Ripper's five "canonical" murders occurred shortly before Bury moved away from Whitechapel. Upon arrest, Bury had remarked to Lieutenant James Parr that he was afraid of being accused of being the Ripper and an acquaintance of his claimed that Bury had thrown down a newspaper with a loud cry after being asked to look up news of the Ripper. However, Ellen Elliott had been strangled to death and had only light cuts to her abdomen, whereas the victims of the Ripper had their throats cut and had much more extensive abdominal wounds.

Thomas Neill Cream

Dr. Thomas Neill Cream (27 May 1850 – 15 November 1892) was a doctor secretly specialising in abortions. He was born in

Dr. Thomas Neill Cream (27 May 1850 – 15 November 1892) was a doctor secretly specialising in abortions. He was born in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, educated in London and Canada, and entered practice in Canada and later in Chicago, Illinois

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

. In 1881 he was found guilty of the fatal poisoning of his mistress's husband. He was imprisoned in the Illinois State Penitentiary in Joliet, Illinois

Joliet ( ) is a city in Will County, Illinois, Will and Kendall County, Illinois, Kendall counties in the U.S. state of Illinois, southwest of Chicago. It is the county seat of Will County. At the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the cit ...

, from November 1881 until his release on good behaviour on 31 July 1891. He moved to London, where he resumed killing and was soon arrested. He was hanged on 15 November 1892 at Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

. According to some sources, his last words were reported as being "I am Jack the...", interpreted to mean Jack the Ripper.Evans and Skinner, ''Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell'', p. 212; Rumbelow, p. 206 However, police officials who attended the execution made no mention of this alleged interrupted confession. As he was still imprisoned at the time of the Ripper murders, most authorities consider it impossible for him to have been the culprit. However, Donald Bell suggested that he could have bribed officials and left the prison before his official release, and Sir Edward Marshall-Hall

Sir Edward Marshall Hall, (16 September 1858 – 24 February 1927) was an English barrister who had a formidable reputation as an orator. He successfully defended many people accused of notorious murders and became known as "The Great Defende ...

suspected that his prison term may have been served by a look-alike in his place. Such notions are unlikely and contradict evidence given by the Illinois authorities, newspapers of the time, Cream's solicitors, Cream's family and Cream himself.

Thomas Hayne Cutbush

Thomas Hayne Cutbush (1865–1903) was a medical student sent toLambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, in the London Borough of Lambeth, historically in the County of Surrey. It is situated south of Charing Cross. The population of the London Borough of Lambeth was 303,086 in 2011. The area expe ...

Infirmary in 1891 suffering delusions thought to have been caused by syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

. After stabbing a woman in the backside and attempting to stab a second he was pronounced insane and committed to Broadmoor Hospital

Broadmoor Hospital is a high-security psychiatric hospital in Crowthorne, Berkshire, England. It is the oldest of the three high-security psychiatric hospitals in England, the other two being Ashworth Hospital near Liverpool and Rampton Secure ...

in 1891, where he remained until his death in 1903. In a series of articles in 1894, '' The Sun'' newspaper suggested that Cutbush was the Ripper. There is no evidence that police took the idea seriously, and Melville Macnaghten's memorandum naming the three police suspects Druitt, Kosminski and Ostrog was written to refute the idea that Cutbush was the Ripper. Cutbush was the suspect advanced in the 1993 book ''Jack the Myth'' by A. P. Wolf, who suggested that Macnaghten wrote his memo to protect Cutbush's uncle, a fellow police officer. Another recent writer, Peter Hodgson, considers Cutbush the most likely candidate. David Bullock also firmly believes Cutbush to be the real Ripper in his book.

Frederick Bailey Deeming

Frederick Bailey Deeming (30 July 1853 – 23 May 1892) murdered his first wife and four children in

Frederick Bailey Deeming (30 July 1853 – 23 May 1892) murdered his first wife and four children in Rainhill

Rainhill is a village and civil parish within the Metropolitan Borough of St Helens, in Merseyside, England. The population of the civil parish taken at the 2011 census was 10,853.

Historically part of Lancashire, Rainhill was formerly a townsh ...

near St. Helens, Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

, in 1891. His crimes went undiscovered and later that year he emigrated to Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

with his second wife, whom he then also murdered. Her body was found buried under their house, and the subsequent investigation led to the discovery of the other bodies in England. He was arrested, sent to trial, and found guilty. He wrote in a book, and later boasted in jail that he was Jack the Ripper, but he was either imprisoned or in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

at the time of the Ripper murders. The police denied any connection between Deeming and the Ripper. He was hanged in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

. According to Robert Napper, a former Scotland Yard detective, the British police did not consider him a suspect because of his two possible alibis but Napper believed Deeming was not in jail at the time, and there is some evidence that he was back in England.

Carl Feigenbaum

Carl Ferdinand Feigenbaum (alias Anton Zahn; 1840 – 27 April 1896) was a German merchant seaman arrested in 1894 inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

for cutting the throat of Mrs Juliana Hoffmann. After his execution, his lawyer, William Sanford Lawton, claimed that Feigenbaum had admitted to having a hatred of women and a desire to kill and mutilate them. Lawton further stated that he believed Feigenbaum was Jack the Ripper. Though covered by the press at the time, the idea was not pursued for more than a century. Using Lawton's accusation as a base, author Trevor Marriott, a former British murder squad detective, argued that Feigenbaum was responsible for the Ripper murders as well as other murders in the United States and Germany between 1891 and 1894. According to Wolf Vanderlinden, some of the murders listed by Marriott did not actually occur; the newspapers often embellished or created Ripper-like stories to boost sales. Lawton's accusations were disputed by a partner in his legal firm, Hugh O. Pentecost, and there is no proof that Feigenbaum was in Whitechapel at the time of the murders. Xanthé Mallett

Xanthé Danielle Mallett (; born 17 December 1976) is a Scottish forensic anthropologist, criminologist and television presenter. She specialises in human craniofacial biometrics and hand identification, and behaviour patterns of paedophiles, p ...

, a Scottish forensic anthropologist and criminologist who investigated the case in 2011, wrote there is considerable doubt that all of the Jack the Ripper murders were committed by the same person. She concludes that "Feigenbaum could have been responsible for one, some or perhaps all" of the Whitechapel murders.

Robert Donston Stephenson

Robert Donston Stephenson (also known as Roslyn D'Onston; 20 April 1841 – 9 October 1916) was a journalist and writer interested in the

Robert Donston Stephenson (also known as Roslyn D'Onston; 20 April 1841 – 9 October 1916) was a journalist and writer interested in the occult

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism a ...

and black magic

Black magic, also known as dark magic, has traditionally referred to the use of supernatural powers or magic for evil and selfish purposes, specifically the seven magical arts prohibited by canon law, as expounded by Johannes Hartlieb in 145 ...

. He admitted himself as a patient at the London Hospital

The Royal London Hospital is a large teaching hospital in Whitechapel in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is part of Barts Health NHS Trust. It provides district general hospital services for the City of London and Tower Hamlets and sp ...

in Whitechapel shortly before the murders started, and left shortly after they ceased. He wrote a newspaper article in which he claimed that black magic was the motive for the killings and alleged that the Ripper was a Frenchman. Stephenson's strange manner and interest in the crimes resulted in an amateur detective reporting him to Scotland Yard on Christmas Eve, 1888. Two days later Stephenson reported his own suspect, a Dr Morgan Davies of the London Hospital. Subsequently, he fell under the suspicion of newspaper editor William Thomas Stead

William Thomas Stead (5 July 184915 April 1912) was a British newspaper editor who, as a pioneer of investigative journalism, became a controversial figure of the Victorian era. Stead published a series of hugely influential campaigns whilst e ...

. In his books on the case, author and historian Melvin Harris

Melvin is a masculine given name and surname, likely a variant of Melville and a descendant of the French surname de Maleuin and the later Melwin. It may alternatively be spelled as Melvyn or, in Welsh, Melfyn and the name Melivinia or Melva may b ...

argued that Stephenson was a leading suspect,Rumbelow, pp. 254–258; Woods and Baddeley, pp. 181–182 but the police do not appear to have treated either him or Dr Davies as serious suspects. London Hospital night-shift rosters and practices indicate that Stephenson was not able to leave on the nights of the murders and hence could not have been Jack the Ripper.

Proposed by later authors

Suspects proposed years after the murders include virtually anyone remotely connected to the case by contemporary documents, as well as many famous names, who were not considered in the police investigation at all. As everyone alive at the time is now dead, modern authors are free to accuse anyone they can, "without any need for any supporting historical evidence".Evans and Rumbelow, p. 261 Most of their suggestions cannot be taken seriously, and include English novelistGeorge Gissing

George Robert Gissing (; 22 November 1857 – 28 December 1903) was an English novelist, who published 23 novels between 1880 and 1903. His best-known works have reappeared in modern editions. They include '' The Nether World'' (1889), '' New Gr ...

, British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

, and syphilitic artist Frank Miles

George Francis Miles (22 April 1852 – 15 July 1891) was a London-based British artist who specialised in pastel portraits of society ladies, also an architect and a keen plantsman. He was artist in chief to the magazine ''Life'', and between 1 ...

.

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale (8 January 1864 – 14 January 1892) was first mentioned in print as a potential suspect when

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale (8 January 1864 – 14 January 1892) was first mentioned in print as a potential suspect when Philippe Jullian

Philippe Jullian (real name: ''Philippe Simounet''; 11 July 1919 – 25 September 1977) was a French illustrator, art historian, biographer, aesthete, novelist and dandy.

Early life

Jullian was born in Bordeaux in 1919. His maternal grandfather ...

's biography of Clarence's father, King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria a ...

, was published in 1962. Jullian made a passing reference to rumours that Clarence might have been responsible for the murders. Though Jullian did not detail the dates or sources of the rumour, it is possible that the rumour derived indirectly from Dr Thomas E. A. Stowell. In 1960, Stowell told the rumour to writer Colin Wilson

Colin Henry Wilson (26 June 1931 – 5 December 2013) was an English writer, philosopher and novelist. He also wrote widely on true crime, mysticism and the paranormal, eventually writing more than a hundred books. Wilson called his phil ...

, who in turn told Harold Nicolson

Sir Harold George Nicolson (21 November 1886 – 1 May 1968) was a British politician, diplomat, historian, biographer, diarist, novelist, lecturer, journalist, broadcaster, and gardener. His wife was the writer Vita Sackville-West.

Early lif ...

, a biographer loosely credited as a source of "hitherto unpublished anecdotes" in Jullian's book. Nicolson could have communicated Stowell's theory to Jullian. The theory was brought to major public attention in 1970 when an article by Stowell was published in ''The Criminologist'' that revealed his suspicion that Clarence had committed the murders after being driven mad by syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

. The suggestion was widely dismissed, as Albert Victor had strong alibis for the murders, and it is unlikely that he suffered from syphilis. Stowell later denied implying that Clarence was the Ripper but efforts to investigate his claims further were hampered, as Stowell was elderly, and he died from natural causes just days after the publication of his article. The same week, Stowell's son reported that he had burned his father's papers, saying "I read just sufficient to make certain that there was nothing of importance."

Subsequently, conspiracy theorists

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

, such as Stephen Knight in '' Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution'', have elaborated on the supposed involvement of Clarence in the murders. Rather than implicate Albert Victor directly, they claim that he secretly married and had a daughter with a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

shop assistant, and that Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

, British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern p ...

Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

, his Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

friends, and the Metropolitan Police

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

conspired to murder anyone aware of Albert Victor's supposed child. Many facts contradict this theory and its originator, Joseph Gorman (also known as Joseph Sickert), later retracted the story and admitted to the press that it was a hoax. Variations of the theory involve the physician William Gull

Sir William Withey Gull, 1st Baronet (31 December 181629 January 1890) was an English physician. Of modest family origins, he established a lucrative private practice and served as Governor of Guy's Hospital, Fullerian Professor of Physiology ...

, the artist Walter Sickert

Walter Richard Sickert (31 May 1860 – 22 January 1942) was a German-born British painter and printmaker who was a member of the Camden Town Group of Post-Impressionist artists in early 20th-century London. He was an important influence on d ...

, and the poet James Kenneth Stephen

James Kenneth Stephen (25 February 1859 – 3 February 1892) was an English poet, and tutor to Prince Albert Victor, eldest son of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales.

Early life

James Kenneth Stephen was the second son of Sir James Fitzjame ...

to greater or lesser degrees, and have been fictionalised in novels and films, such as ''Murder by Decree

''Murder by Decree'' is a 1979 mystery thriller film directed by Bob Clark. It features the Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson characters created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who are embroiled in the investigation surrounding the real-life 1 ...

'' and ''From Hell

''From Hell'' is a graphic novel by writer Alan Moore and artist Eddie Campbell, originally published in serial form from 1989 to 1998. The full collection was published in 1999 by Top Shelf Productions.

Set during the Whitechapel murders of ...

''.

Joseph Barnett

Joseph Barnett (c. 1858–1927) was a former fish porter, and victim Mary Kelly's lover from 8 April 1887 to 30 October 1888, when they quarrelled and separated after he lost his job and she returned to prostitution to make a living. Inspector Abberline questioned him for four hours after Kelly's murder, and his clothes were examined for bloodstains, but he was then released without charge. A century after the murders, author Bruce Paley proposed him as a suspect as Kelly's scorned or jealous lover, and suggested that he'd committed the other murders to scare Kelly off the streets and out of prostitution.Rumbelow, p. 262; Whitehead and Rivett, pp. 122–123 Other authors suggest he killed Kelly only, and mutilated the body to make it look like a Ripper murder, but Abberline's investigation appears to have exonerated him. Other acquaintances of Kelly put forward as her murderer include her landlord John McCarthy and her former boyfriend Joseph Fleming.

Joseph Barnett (c. 1858–1927) was a former fish porter, and victim Mary Kelly's lover from 8 April 1887 to 30 October 1888, when they quarrelled and separated after he lost his job and she returned to prostitution to make a living. Inspector Abberline questioned him for four hours after Kelly's murder, and his clothes were examined for bloodstains, but he was then released without charge. A century after the murders, author Bruce Paley proposed him as a suspect as Kelly's scorned or jealous lover, and suggested that he'd committed the other murders to scare Kelly off the streets and out of prostitution.Rumbelow, p. 262; Whitehead and Rivett, pp. 122–123 Other authors suggest he killed Kelly only, and mutilated the body to make it look like a Ripper murder, but Abberline's investigation appears to have exonerated him. Other acquaintances of Kelly put forward as her murderer include her landlord John McCarthy and her former boyfriend Joseph Fleming.

Lewis Carroll

Lewis Carroll (

Lewis Carroll (pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898) was the author of ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (commonly ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English novel by Lewis Carroll. It details the story of a young girl named Alice (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland), Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a ...

'' and ''Through the Looking-Glass

''Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There'' (also known as ''Alice Through the Looking-Glass'' or simply ''Through the Looking-Glass'') is a novel published on 27 December 1871 (though indicated as 1872) by Lewis Carroll and the ...

''. He was named as a suspect based upon anagram

An anagram is a word or phrase formed by rearranging the letters of a different word or phrase, typically using all the original letters exactly once. For example, the word ''anagram'' itself can be rearranged into ''nag a ram'', also the word ...

s which author Richard Wallace devised for his book ''Jack the Ripper, Light-Hearted Friend

''Jack the Ripper, Light-Hearted Friend'' is a 1996 book by Richard Wallace (author), Richard Wallace in which Wallace proposed a theory that British author Lewis Carroll, whose real name was Charles L. Dodgson (1832–1898), and his colleague Th ...

.''Was Lewis Carroll Jack the Ripper?Oxford Mail

''Oxford Mail'' is a daily tabloid newspaper in Oxford, England, owned by Newsquest. It is published six days a week. It is a sister paper to the weekly tabloid ''The Oxford Times''.

History

The ''Oxford Mail'' was founded in 1928 as a success ...

; 24 February 1999 Wallace argues that Carroll had a psychotic breakdown after being assaulted by a man when he was 12. Moreover, according to Wallace, Carroll wrote a diary every day in purple ink, but on the days of the Whitechapel killings, he switched to black. This claim is not taken seriously by scholars. When an excerpt of Wallace's book appeared in ''Harper's'', a letter to the editor cleverly debunked the idea that the anagrams which Wallace had produced from Carroll's work were meaningful: the authors of the letter, Guy Jacobson and Francis Heaney, took the first paragraph of Wallace's excerpt and produced an impressive anagram that had Wallace confessing to the murder of Nicole Brown and the framing of O. J. Simpson, thus demonstrating how incriminating anagrams could be produced from any reasonably lengthy passage.

Willy Clarkson

William Berry "Willy" Clarkson (1861 – 12 October 1934) was the royal wigmaker and costume-maker to Queen Victoria and lived approximately two miles from each of the canonical five crime scenes. He was first named as a suspect in 2019, with many of the assertions based on Clarkson's 1937 biography written by Harry J. Greenwall. Clarkson is known to have stalked his ex-fiancée and was reputedly a blackmailer and arsonist. He is suspected of committing the murders to cover up his blackmail schemes. Evidence presented to support the theory of Clarkson as a suspect included the revelation that he admitted one of his custom-made wigs was found near the scene of one of the Ripper killings, a fact not previously widely known in the Ripperology community. Additionally, Clarkson's biography quotes him as stating that the police obtained disguises from him for their search for the Ripper, and as such, he would have been aware of the trails they followed, allowing him to elude capture. Hair-cutting shears and barber-surgeon tools (his father or grandfather allegedly being a barber-surgeon) of the kind used by a wig-maker at the time closely match the shape and style of the weapons suspected to have been used in the murders.

William Berry "Willy" Clarkson (1861 – 12 October 1934) was the royal wigmaker and costume-maker to Queen Victoria and lived approximately two miles from each of the canonical five crime scenes. He was first named as a suspect in 2019, with many of the assertions based on Clarkson's 1937 biography written by Harry J. Greenwall. Clarkson is known to have stalked his ex-fiancée and was reputedly a blackmailer and arsonist. He is suspected of committing the murders to cover up his blackmail schemes. Evidence presented to support the theory of Clarkson as a suspect included the revelation that he admitted one of his custom-made wigs was found near the scene of one of the Ripper killings, a fact not previously widely known in the Ripperology community. Additionally, Clarkson's biography quotes him as stating that the police obtained disguises from him for their search for the Ripper, and as such, he would have been aware of the trails they followed, allowing him to elude capture. Hair-cutting shears and barber-surgeon tools (his father or grandfather allegedly being a barber-surgeon) of the kind used by a wig-maker at the time closely match the shape and style of the weapons suspected to have been used in the murders.

David Cohen

David Cohen (1865 – 20 October 1889) was a 23 year-old Polish Jew whose incarceration at Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum on 7 December 1888 roughly coincided with the end of the murders. An unmarried tailor, Cohen was described as a violently antisocial, poor East End local. He was suggested as a suspect by author and RipperologistMartin Fido

Martin Austin Fido (18 October 1939 – 2 April 2019) was a university professor, true crime writer and broadcaster. His many books include ''The Crimes, Detection and Death of Jack the Ripper'', ''The Official Encyclopedia of Scotland Yard'', ' ...

in his book ''The Crimes, Detection and Death of Jack the Ripper'' (1987).

Fido claimed that the name "David Cohen" was a generic substitute, used at that time to refer to any Jewish immigrant who either could not be positively identified, or whose name was too difficult for police to spell, much in the same fashion that "John Doe

John Doe (male) and Jane Doe (female) are multiple-use placeholder names that are used when the true name of a person is unknown or is being intentionally concealed. In the context of law enforcement in the United States, such names are often ...

" is used in the United States today.Fido quoted in Rumbelow, pp. 180–181 Fido identified Cohen with "Leather Apron" (see John Pizer above), and speculated that Cohen's true identity was Nathan Kaminsky, a bootmaker living in Whitechapel who had been treated at one time for syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

, and who could not be traced after mid-1888: The same time that Cohen appeared. Fido believed that police officials confused the name Kaminsky with Kosminski, resulting in the wrong man coming under suspicion (see Aaron Kosminski

Aaron Kosminski (born Aron Mordke Kozmiński; 11 September 1865 – 24 March 1919) was a Polish barber and hairdresser, and suspect in the Jack the Ripper case.

Kosminski was a Polish Jew who emigrated from Congress Poland to England in the 18 ...

above).

Cohen exhibited violent, destructive tendencies while at the asylum, and had to be restrained. He died at the asylum in October 1889. In his book ''The Cases That Haunt Us'', former FBI criminal profiler John Douglas asserted that behavioural clues gathered from the murders all point to a person "known to the police as David Cohen ... or someone very much like him".

William Withey Gull

Sir William Withey Gull, Bt (31 December 1816 – 29 January 1890) was physician-in-ordinary to

Sir William Withey Gull, Bt (31 December 1816 – 29 January 1890) was physician-in-ordinary to Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

. He was named as the Ripper as part of the evolution of the widely discredited Masonic

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to Fraternity, fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of Stonemasonry, stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their inte ...

/royal conspiracy theory outlined in such books as '' Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution''. Coachman John Netley has been named as his accomplice. Thanks to the popularity of this theory among fiction writers and for its dramatic nature, Gull shows up as the Ripper in a number of books and films including the TV film ''Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in the autumn of 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer wa ...

'' (1988), Alan Moore

Alan Moore (born 18 November 1953) is an English author known primarily for his work in comic books including ''Watchmen'', ''V for Vendetta'', ''The Ballad of Halo Jones'', ''Swamp Thing'', ''Batman:'' ''The Killing Joke'', and ''From Hell' ...

and Eddie Campbell

Eddie Campbell (born 10 August 1955) is a British comics artist and cartoonist who now lives in Chicago. Probably best known as the illustrator and publisher of ''From Hell'' (written by Alan Moore), Campbell is also the creator of the semi-au ...

's graphic novel ''From Hell

''From Hell'' is a graphic novel by writer Alan Moore and artist Eddie Campbell, originally published in serial form from 1989 to 1998. The full collection was published in 1999 by Top Shelf Productions.

Set during the Whitechapel murders of ...

'' (1999), and its 2001 film adaptation, in which Ian Holm

Sir Ian Holm Cuthbert (12 September 1931 – 19 June 2020) was an English actor who was knighted in 1998 for his contributions to theatre and film. Beginning his career on the British stage as a standout member of the Royal Shakespeare Company ...

plays Gull. Conventional historians have never taken Gull seriously as a suspect due to sheer lack of evidence; in addition, he was in his seventies at the time of the murders and had recently suffered a stroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

.

George Hutchinson

George Hutchinson was an unemployed labourer. On 12 November 1888, he made a formal statement to the London police that in the early hours of 9 November 1888, Mary Jane Kelly approached him in the street and asked him for money. He stated that he had then followed her and another man of conspicuous appearance to her room, and had watched the room for about three-quarters of an hour without seeing either leave. He gave a very detailed description of the man, claiming he was "of Jewish appearance", despite the darkness of that night. The accuracy of Hutchinson's statement was disputed among the senior police. Inspector Frederick Abberline, after interviewing Hutchinson, believed that Hutchinson's account was truthful. However, Robert Anderson, head of the CID, later claimed that the only witness who got a good look at the killer was Jewish. Hutchinson was not a Jew, and thus not that witness. Hutchinson's statement was made on the day that Mary Kelly's inquest was held, and he was not called to testify. Some modern scholars have suggested that Hutchinson was the Ripper himself, trying to confuse the police with a false description, but others suggest he may have just been an attention seeker who made up a story he hoped to sell to the press.James Kelly

James Kelly (20 April 1860 – 17 September 1929; no relation to victim Mary Kelly) was first identified as a suspect in Terence Sharkey's ''Jack the Ripper. 100 Years of Investigation'' (Ward Lock 1987) and documented in ''Prisoner 1167: The madman who was Jack the Ripper'', by Jim Tully, in 1997.

James Kelly murdered his wife in 1883 by stabbing her in the neck. Deemed insane, he was committed to the

James Kelly (20 April 1860 – 17 September 1929; no relation to victim Mary Kelly) was first identified as a suspect in Terence Sharkey's ''Jack the Ripper. 100 Years of Investigation'' (Ward Lock 1987) and documented in ''Prisoner 1167: The madman who was Jack the Ripper'', by Jim Tully, in 1997.

James Kelly murdered his wife in 1883 by stabbing her in the neck. Deemed insane, he was committed to the Broadmoor Asylum

Broadmoor Hospital is a high-security psychiatric hospital in Crowthorne, Berkshire, England. It is the oldest of the three high-security psychiatric hospitals in England, the other two being Ashworth Hospital near Liverpool and Rampton Secure ...

, from which he later escaped in early 1888, using a key he fashioned himself. After the last of the five canonical Ripper murders in London in November 1888, the police searched for Kelly at what had been his residence prior to his wife's murder, but they were not able to locate him. In 1927, almost forty years after his escape, he unexpectedly turned himself in to officials at the Broadmoor Asylum. He died two years later, presumably of natural causes.

Retired New York Police Department cold-case detective Ed Norris

Edward T. Norris (born April 10, 1960) is an American radio host and former law enforcement officer in Maryland. He is the cohost of a talk show on WJZ-FM (105.7 The Fan) in Baltimore, Maryland. Norris, a 20-year veteran of the New York Police ...

examined the Jack the Ripper case for a Discovery Channel programme called ''Jack the Ripper in America''. In it, Norris claims that James Kelly was Jack the Ripper and that he was also responsible for multiple murders in cities around the United States. Norris highlights a few features of the Kelly story to support his contention. Norris reported Kelly's Broadmoor Asylum file from before his escape and his eventual return had never been opened since 1927 until Norris was given special permission for access to it, and that the file is the perfect profile match for Jack the Ripper.

Charles Allen Lechmere

Charles Allen Lechmere (5 October 1849 – 23 December 1920), also known as Charles Cross, was a meat cart driver for the Pickfords company, and is conventionally regarded as an innocent witness who discovered the body of the first canonical Ripper victim,

Charles Allen Lechmere (5 October 1849 – 23 December 1920), also known as Charles Cross, was a meat cart driver for the Pickfords company, and is conventionally regarded as an innocent witness who discovered the body of the first canonical Ripper victim, Mary Ann Nichols

Mary Ann Nichols, known as Polly Nichols (née Walker; 26 August 184531 August 1888), was the first canonical victim of the unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, who is believed to have murdered and mutilated at least five women i ...

. In a documentary titled ''Jack the Ripper: The New Evidence'', Swedish journalist Christer Holmgren and criminologist Gareth Norris of Aberystwyth University

, mottoeng = A world without knowledge is no world at all

, established = 1872 (as ''The University College of Wales'')

, former_names = University of Wales, Aberystwyth

, type = Public

, endowment = ...

, with assistance from former detective Andy Griffiths, proposed that Lechmere was the Ripper. According to Holmgren, Lechmere lied to police, claiming that he had been with Nichols's body for a few minutes, whereas research on his route to work from his home demonstrated that he must have been with her for about nine minutes.