John Of Brienne on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John of Brienne ( 1170 – 19–23 March 1237), also known as John I, was King of Jerusalem from 1210 to 1225 and Latin Emperor of Constantinople from 1229 to 1237. He was the youngest son of

John landed at Acre on 13 September 1210; the following day, Patriarch of Jerusalem

John landed at Acre on 13 September 1210; the following day, Patriarch of Jerusalem

Andrew II decided to return home, leaving the crusaders' camp with Hugh I and Bohemond IV in early 1218. Although military action was suspended after their departure, the crusaders restored fortifications at Caesarea and

Andrew II decided to return home, leaving the crusaders' camp with Hugh I and Bohemond IV in early 1218. Although military action was suspended after their departure, the crusaders restored fortifications at Caesarea and

He left for Italy in October 1222 to attend a conference about a new crusade. At John's request, Pope Honorius declared that all lands conquered during the crusade should be united with the Kingdom of Jerusalem. To plan the military campaign, the pope and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II met at

He left for Italy in October 1222 to attend a conference about a new crusade. At John's request, Pope Honorius declared that all lands conquered during the crusade should be united with the Kingdom of Jerusalem. To plan the military campaign, the pope and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II met at

The Latin Emperor of Constantinople, Robert I, died in January 1228. His brother Baldwin II succeeded him, but a regent was needed to rule the Latin Empire since Baldwin was ten years old.

The Latin Emperor of Constantinople, Robert I, died in January 1228. His brother Baldwin II succeeded him, but a regent was needed to rule the Latin Empire since Baldwin was ten years old.

Erard II of Brienne Erard II of Brienne (died 1191) was count of Brienne from 1161 to 1191, and a French general during the Third Crusade, most notably at the Siege of Acre. He was the son of Gautier II, count of Brienne, and Adèle of Baudemont, daughter of Andrew, l ...

, a wealthy nobleman in Champagne

Champagne (, ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, that demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, ...

. John, originally destined for an ecclesiastical career, became a knight and owned small estates in Champagne around 1200. After the death of his brother, Walter III, he ruled the County of Brienne

The County of Brienne was a medieval county in France centered on Brienne-le-Château.

Counts of Brienne

* Engelbert I

* Engelbert II

* Engelbert III

* Engelbert IV

* Walter I (? – c. 1090)

* Erard I (c. 1090 – c. 1120?)

* Walter I ...

on behalf of his minor nephew Walter IV (who lived in southern Italy).

The barons of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem ( la, Regnum Hierosolymitanum; fro, Roiaume de Jherusalem), officially known as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem or the Frankish Kingdom of Palestine,Example (title of works): was a Crusader state that was establish ...

proposed that John marry their queen, Maria

Maria may refer to:

People

* Mary, mother of Jesus

* Maria (given name), a popular given name in many languages

Place names Extraterrestrial

* 170 Maria, a Main belt S-type asteroid discovered in 1877

* Lunar maria (plural of ''mare''), large, ...

. With the consent of Philip II of France

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), byname Philip Augustus (french: Philippe Auguste), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks, but from 1190 onward, Philip became the first French m ...

and Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 ...

, he left France for the Holy Land and married the queen; the couple were crowned in 1210. After Maria's death in 1212 John administered the kingdom as regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

for their infant daughter, Isabella II; an influential lord, John of Ibelin, attempted to depose him. John was a leader of the Fifth Crusade

The Fifth Crusade (1217–1221) was a campaign in a series of Crusades by Western Europeans to reacquire Jerusalem and the rest of the Holy Land by first conquering Egypt, ruled by the powerful Ayyubid sultanate, led by Al-Adil I, al-Adil, brothe ...

. Although his claim of supreme command of the crusader army was never unanimously acknowledged, his right to rule Damietta (in Egypt) was confirmed shortly after the town fell to the crusaders in 1219. He claimed the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia on behalf of his second wife, Stephanie

Stephanie is a female name that comes from the Greek name Στέφανος (Stephanos) meaning "crown". The male form is Stephen. Forms of Stephanie in other languages include the German "Stefanie", the Italian, Czech, Polish, and Russian "St ...

, in 1220. After Stephanie and their infant son died that year, John returned to Egypt. The Fifth Crusade ended in failure (including the recovery of Damietta by the Egyptians) in 1221.

John was the first king of Jerusalem to visit Europe (Italy, France, England, León, Castile and Germany) to seek assistance for the Holy Land. He gave his daughter in marriage to Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in 1225, and Frederick ended John's rule of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Although the popes tried to persuade Frederick to restore the kingdom to John, the Jerusalemite barons regarded Frederick as their lawful ruler. John administered papal domains in Tuscany, became the '' podestà'' of Perugia

Perugia (, , ; lat, Perusia) is the capital city of Umbria in central Italy, crossed by the River Tiber, and of the province of Perugia.

The city is located about north of Rome and southeast of Florence. It covers a high hilltop and pa ...

and was a commander of Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX ( la, Gregorius IX; born Ugolino di Conti; c. 1145 or before 1170 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decre ...

's army during Gregory's war against Frederick in 1228 and 1229.

He was elected emperor in 1229 as the senior co-ruler (with Baldwin II) of the Latin Empire

The Latin Empire, also referred to as the Latin Empire of Constantinople, was a feudal Crusader state founded by the leaders of the Fourth Crusade on lands captured from the Byzantine Empire. The Latin Empire was intended to replace the Byzant ...

, and was crowned in Constantinople in 1231. John III Vatatzes, Emperor of Nicaea

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as le ...

, and Ivan Asen II of Bulgaria

Ivan Asen II, also known as John Asen II ( bg, Иван Асен II, ; 1190s – May/June 1241), was Emperor (Tsar) of Bulgaria from 1218 to 1241. He was still a child when his father Ivan Asen I one of the founders of the Second Bulgarian Empi ...

occupied the last Latin territories in Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

and Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, besieging Constantinople in early 1235. John directed the defence of his capital during the months-long siege, with the besiegers withdrawing only after Geoffrey II of Achaea and united fleets from Italian towns defeated their fleet in 1236. The following year, John died as a Franciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

friar.

Early life

John was the youngest of the four sons of CountErard II of Brienne Erard II of Brienne (died 1191) was count of Brienne from 1161 to 1191, and a French general during the Third Crusade, most notably at the Siege of Acre. He was the son of Gautier II, count of Brienne, and Adèle of Baudemont, daughter of Andrew, l ...

and Agnes of Montfaucon. He seemed "exceedingly about 80"George Akropolites: ''The History'' (ch. 27.), p. 184. to the 14-year-old George Akropolites George Akropolites ( Latinized as Acropolites or Acropolita; el, , ''Georgios Akropolites''; 1217 or 1220 – 1282) was a Byzantine Greek historian and statesman born at Constantinople.

Life

In his sixteenth year he was sent by his father, t ...

in 1231; if Akropolites' estimate was correct, John was born around 1150. However, no other 13th-century authors described John as an old man. His father referred to John's brothers as "children" in 1177 and mentioned the tutor of John's oldest brother, Walter III, in 1184; this suggests that John's brothers were born in the late 1160s. Modern historians agree that John was born after 1168, probably during the 1170s.

Although his father destined John for a clerical career, according to the late-13th-century ''Tales of the Minstrel of Reims'' he "was unwilling". Instead, the minstrel continued, John fled to his maternal uncle at the Clairvaux Abbey

Clairvaux Abbey (, ; la, Clara Vallis) was a Cistercian monastery in Ville-sous-la-Ferté, from Bar-sur-Aube. The original building, founded in 1115 by St. Bernard, is now in ruins; the present structure dates from 1708. Clairvaux Abbey was ...

. Encouraged by his fellows, he became a knight and earned a reputation in tournaments

A tournament is a competition involving at least three competitors, all participating in a sport or game. More specifically, the term may be used in either of two overlapping senses:

# One or more competitions held at a single venue and concentr ...

and fights. Although elements of the ''Tales of the Minstrel of Reims'' are apparently invented (for instance, John did not have a maternal uncle in Clairvaux), historian Guy Perry wrote that it may have preserved details of John's life. A church career was not unusual for youngest sons of 12th-century noblemen in France; however, if his father sent John to a monastery he left before reaching the age of taking monastic vows. John "clearly developed the physique that was necessary to fight well" in his youth, because the 13th-century sources Akropolites and Salimbene di Adam

Salimbene di Adam, O.F.M., (or Salimbene of Parma) (9 October 1221 – 1290) was an Italian Franciscan friar, theologian, and chronicler who is a source for Italian history of the 13th century.

Life

He was born in Parma, the son of Guido di A ...

emphasize his physical strength.

Erard II joined the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by three European monarchs of Western Christianity (Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor) to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by ...

and died in the Holy Land in 1191. His oldest son, Walter III, succeeded him in Brienne. John was first mentioned in an 1192 (or 1194) charter issued by his brother, indicating that he was a prominent figure in Walter's court. According to a version of Ernoul Ernoul was a squire of Balian of Ibelin who wrote an eyewitness account of the fall of Jerusalem in 1187. This was later incorporated into an Old French history of Crusader Palestine now known as the ''Chronicle of Ernoul and Bernard the Treasurer ...

's chronicle, John participated in a war against Peter II of Courtenay

Peter, also Peter II of Courtenay (french: Pierre de Courtenay; died 1219), was emperor of the Latin Empire of Constantinople from 1216 to 1217.

Biography

Peter II was a son of Peter I of Courtenay (died 1183), a younger son of Louis VI of Fra ...

. Although the ''Tales of the Minstrel of Reims'' claimed that he was called "John Lackland", according to contemporary charters John held Jessains, Onjon, Trannes

Trannes () is a commune in the Aube department in north-central France.

Population

See also

* Communes of the Aube department

*Parc naturel régional de la Forêt d'Orient

Orient Forest Regional Natural Park ( French: ''Parc naturel r� ...

and two other villages in the County of Champagne

The County of Champagne ( la, Comitatus Campaniensis; fro, Conté de Champaigne), or County of Champagne and Brie (region), Brie, was a historic territory and Feudalism, feudal principality in France descended from the early medieval kingdom of ...

around 1200. In 1201, Theobald III granted him additional estates in Mâcon

Mâcon (), historically anglicised as Mascon, is a city in east-central France. It is the prefecture of the department of Saône-et-Loire in Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. Mâcon is home to near 34,000 residents, who are referred to in French as ...

, Longsols and elsewhere. Theobald's widow, Blanche of Navarre, persuaded John to sell his estate at Mâcon, saying that it was her dower

Dower is a provision accorded traditionally by a husband or his family, to a wife for her support should she become widowed. It was settled on the bride (being gifted into trust) by agreement at the time of the wedding, or as provided by law. ...

.

Walter III of Brienne died in June 1205 while fighting in southern Italy. His widow, Elvira of Sicily, gave birth to a posthumous son

A posthumous birth is the birth of a child after the death of a biological parent. A person born in these circumstances is called a posthumous child or a posthumously born person. Most instances of posthumous birth involve the birth of a child af ...

, Walter IV, who grew up in Italy. John assumed the title of count of Brienne

The County of Brienne was a medieval county in France centered on Brienne-le-Château.

Counts of Brienne

* Engelbert I

* Engelbert II

* Engelbert III

* Engelbert IV

* Walter I (? – c. 1090)

* Erard I (c. 1090 – c. 1120?)

* Walter II ...

, and began administering the county on his nephew's behalf in 1205 or 1206. As a leading vassal of the count of Champagne, John frequented the court of Blanche of Navarre, who ruled Champagne during the minority of her son, Theobald IV. According to a version of Ernoul's chronicle, she loved John "more than any man in the world"; this annoyed King Philip II of France

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), byname Philip Augustus (french: Philippe Auguste), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks, but from 1190 onward, Philip became the first French m ...

.

The two versions of Ernoul's chronicle tell different stories about John's ascent to the throne of Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

. According to one version, the leading lords of Jerusalem sent envoys to France in 1208 asking Philip II to select a French nobleman as a husband for their queen, Maria

Maria may refer to:

People

* Mary, mother of Jesus

* Maria (given name), a popular given name in many languages

Place names Extraterrestrial

* 170 Maria, a Main belt S-type asteroid discovered in 1877

* Lunar maria (plural of ''mare''), large, ...

. Taking advantage of the opportunity to rid himself of John, Philip II suggested him. In the other version an unnamed knight encouraged the Jerusalemite lords to select John, who accepted their offer with Philip's consent. John visited Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 ...

in Rome. The pope donated 40,000 marks for the defence of the Holy Land, stipulating that John could spend the money only with the consent of the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem and the grand masters

Grand may refer to:

People with the name

* Grand (surname)

* Grand L. Bush (born 1955), American actor

* Grand Mixer DXT, American turntablist

* Grand Puba (born 1966), American rapper

Places

* Grand, Oklahoma

* Grand, Vosges, village and c ...

of the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

.

King of Jerusalem

Co-ruler

Albert of Vercelli

Albert of Jerusalem (''Albertus Hierosolymitanus; Albertus Vercelensis,'' also ''Saint Albert'', ''Albert of Vercelli'' or ''Alberto Avogadro''; died 14 September 1214) was a canon lawyer and saint. He was Bishop of Bobbio and Bishop of Vercelli, ...

married him to Queen Maria. John and Maria were crowned in the Cathedral of Tyre on 3 October. The truce concluded by Maria's predecessor Aimery and the Ayyubid sultan Al-Adil I

Al-Adil I ( ar, العادل, in full al-Malik al-Adil Sayf ad-Din Abu-Bakr Ahmed ibn Najm ad-Din Ayyub, ar, الملك العادل سيف الدين أبو بكر بن أيوب, "Ahmed, son of Najm ad-Din Ayyub, father of Bakr, the Just ...

had ended by John's arrival. Although Al-Adil was willing to renew it, Jerusalemite lords did not want to sign a new treaty without John's consent. During John and Maria's coronation, Al-Adil's son Al-Mu'azzam Isa pillaged the area around Acre but did not attack the city. After returning to Acre, John raided nearby Muslim settlements in retaliation.

Although about 300 French knights accompanied him to the Holy Land, no influential noblemen joined him; they preferred participating in the French Albigensian Crusade or did not see him as sufficiently eminent. John's cousin, Walter of Montbéliard, joined him only after he was expelled from Cyprus. Montbéliard led a naval expedition to Egypt to plunder the Nile Delta. After most of the French crusaders left the Holy Land, John forged a new truce with Al-Adil by the middle of 1211 and sent envoys to Pope Innocent urging him to preach a new crusade.

Conflicts

Maria died shortly after giving birth to their daughter,Isabella

Isabella may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Isabella (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Isabella (surname), including a list of people

Places

United States

* Isabella, Alabama, an unincorpor ...

, in late 1212. Her death triggered a legal dispute, with John of Ibelin (who administered Jerusalem before John's coronation) questioning the widowed king's right to rule. The king sent Raoul of Merencourt, Bishop of Sidon The Roman Catholic Diocese of Sidon was a bishopric in the Kingdom of Jerusalem in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Establishment

Before the arrival of the crusaders to Syria in the late 11th century, the Orthodox bishops of Sidon had been suffragans ...

, to Rome for assistance from the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

. Pope Innocent confirmed John as lawful ruler of the Holy Land in early 1213, urging the prelates to support him with ecclesiastical sanctions if needed. Most of the Jerusalemite lords remained loyal to the king, acknowledging his right to administer the kingdom on behalf of his infant daughter; John of Ibelin left the Holy Land and settled in Cyprus.

The relationship between John of Brienne and Hugh I of Cyprus

Hugh I (french: Hugues; gr, Ούγος; 1194/1195 – 10 January 1218) succeeded to the throne of Cyprus on 1 April 1205 underage upon the death of his elderly father Aimery, King of Cyprus and Jerusalem. His mother was Eschiva of Ibelin, heir ...

was tense. Hugh ordered the imprisonment of John's supporters in Cyprus, releasing them only at Pope Innocent's command. During the War of the Antiochene Succession John sided with Bohemond IV of Antioch

Bohemond IV of Antioch, also known as Bohemond the One-Eyed (french: Bohémond le Borgne; 1175–1233), was Count of Tripoli from 1187 to 1233, and Prince of Antioch from 1201 to 1216 and from 1219 to 1233. He was the younger son of Bohemond III ...

and the Templars against Raymond-Roupen of Antioch

Raymond-Roupen (also Raymond-Rupen and Ruben-Raymond; 1198 – 1219 or 1221/1222) was a member of the House of Poitiers who claimed the thrones of the Principality of Antioch and Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. His succession in Antioch was preven ...

and Leo I

The LEO I (Lyons Electronic Office I) was the first computer used for commercial business applications.

The prototype LEO I was modelled closely on the Cambridge EDSAC. Its construction was overseen by Oliver Standingford, Raymond Thompson and ...

, King of Cilician Armenia, who were supported by Hugh and the Hospitallers. However, John sent only 50 knights to fight the Armenians in Antiochia in 1213. Leo I concluded a peace treaty with the Knights Templar late that year, and he and John reconciled. John married Leo's oldest daughter, Stephanie

Stephanie is a female name that comes from the Greek name Στέφανος (Stephanos) meaning "crown". The male form is Stephen. Forms of Stephanie in other languages include the German "Stefanie", the Italian, Czech, Polish, and Russian "St ...

(also known as Rita), in 1214 and Stephanie received a dowry of 30,000 bezant

In the Middle Ages, the term bezant (Old French ''besant'', from Latin ''bizantius aureus'') was used in Western Europe to describe several gold coins of the east, all derived ultimately from the Roman ''solidus''. The word itself comes from th ...

s. Quarrels among John, Leo I, Hugh I and Bohemond IV are documented by Pope Innocent's letters urging them to reconcile their differences before the Fifth Crusade

The Fifth Crusade (1217–1221) was a campaign in a series of Crusades by Western Europeans to reacquire Jerusalem and the rest of the Holy Land by first conquering Egypt, ruled by the powerful Ayyubid sultanate, led by Al-Adil I, al-Adil, brothe ...

reached the Holy Land.

Fifth Crusade

Pope Innocent proclaimed the Fifth Crusade in 1213, with the "liberation of the Holy Land" (the reconquest ofJerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

) its principal object. The first crusader troops, commanded by Leopold VI of Austria

Leopold VI (15 October 1176 – 28 July 1230), known as Leopold the Glorious, was Duke of Styria from 1194 and Duke of Austria from 1198 to his death in 1230. He was a member of the House of Babenberg.

Biography

Leopold VI was the younger son ...

, landed at Acre in early September 1217. Andrew II of Hungary

Andrew II ( hu, II. András, hr, Andrija II., sk, Ondrej II., uk, Андрій II; 117721 September 1235), also known as Andrew of Jerusalem, was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1205 and 1235. He ruled the Principality of Halych from 11 ...

and his army followed that month, and Hugh I of Cyprus and Bohemond IV of Antioch soon joined the crusaders. However, hundreds of crusaders soon returned to Europe because of a famine following the previous year's poor harvest. A war council was held in the tent of Andrew II, who considered himself the supreme commander of the crusader army. Other leaders, particularly John, did not acknowledge Andrew's leadership. The crusaders raided nearby territory ruled by Al-Adil I for food and fodder, forcing the sultan to retreat in November 1217. In December John besieged the Ayyubid fortress on Mount Tabor

Mount Tabor ( he, הר תבור) (Har Tavor) is located in Lower Galilee, Israel, at the eastern end of the Jezreel Valley, west of the Sea of Galilee.

In the Hebrew Bible (Joshua, Judges), Mount Tabor is the site of the Battle of Mount Tabo ...

, joined only by Bohemond IV of Antioch. He was unable to capture it, which "encouraged the infidel", according to the contemporary Jacques de Vitry.

Andrew II decided to return home, leaving the crusaders' camp with Hugh I and Bohemond IV in early 1218. Although military action was suspended after their departure, the crusaders restored fortifications at Caesarea and

Andrew II decided to return home, leaving the crusaders' camp with Hugh I and Bohemond IV in early 1218. Although military action was suspended after their departure, the crusaders restored fortifications at Caesarea and Atlit

Atlit ( he, עַתְלִית, ar, عتليت) is a coastal town located south of Haifa, Israel. The community is in the Hof HaCarmel Regional Council in the Haifa District of Israel.

Off the coast of Atlit is a submerged Neolithic village. At ...

. After new troops arrived from the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

in April, they decided to invade Egypt. They elected John supreme commander, giving him the right to rule the land they would conquer. His leadership was primarily nominal, since he could rarely impose his authority on an army of troops from many countries.

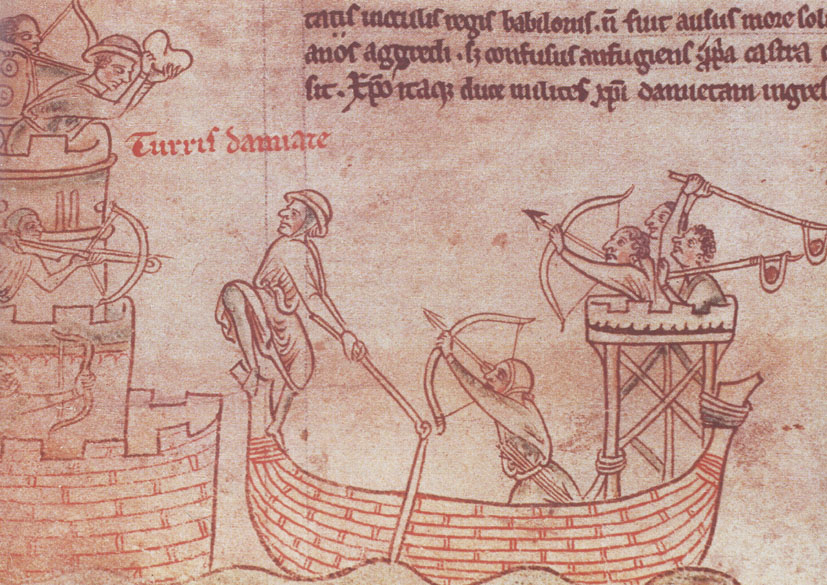

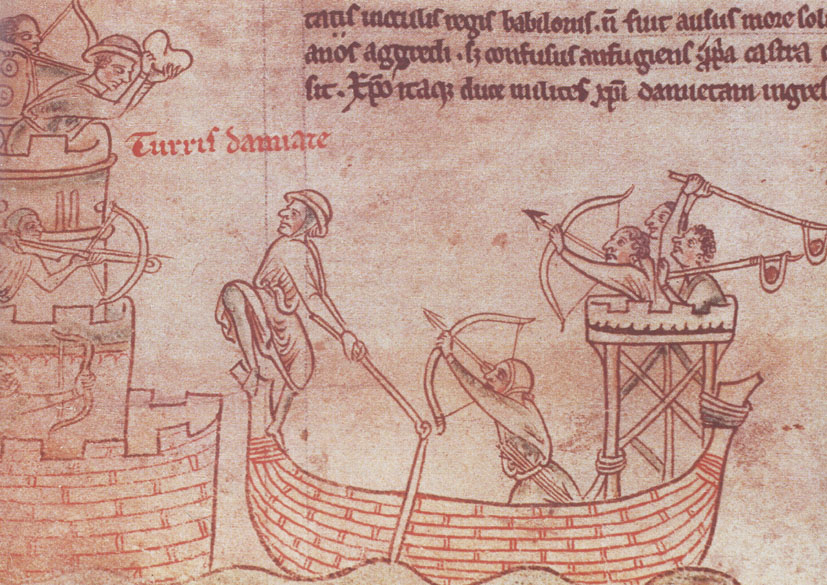

The crusaders laid siege to Damietta, on the Nile, in May 1218. Although they seized a strategically important tower on a nearby island on 24 August, Al-Kamil

Al-Kamil ( ar, الكامل) (full name: al-Malik al-Kamil Naser ad-Din Abu al-Ma'ali Muhammad) (c. 1177 – 6 March 1238) was a Muslim ruler and the fourth Ayyubid sultan of Egypt. During his tenure as sultan, the Ayyubids defeated the Fifth Cr ...

(who had succeeded Al-Adil I in Egypt) controlled traffic on the Nile. In September, reinforcements commanded by Pope Honorius III

Pope Honorius III (c. 1150 – 18 March 1227), born Cencio Savelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 July 1216 to his death. A canon at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, he came to hold a number of impor ...

's legate Cardinal Pelagius (who considered himself the crusade's supreme commander) arrived from Italy.

Egyptian forces attempted a surprise attack on the crusaders' camp on 9 October, but John discovered their movements. He and his retinue attacked and annihilated the Egyptian advance guard, hindering the main force. The crusaders built a floating fortress on the Nile near Damietta, but a storm blew it near the Egyptian camp. The Egyptians seized the fortress, killing nearly all of its defenders. Only two soldiers survived the attack; they were accused of cowardice, and John ordered their execution. Taking advantage of the new Italian troops, Cardinal Pelagius began to intervene in strategic decisions. His debates with John angered their troops. The soldiers broke into the Egyptian camp on 29 August 1219 without an order, but they were soon defeated and nearly annihilated. During the ensuing panic, only the cooperation of John, the Templars, the Hospitallers and the noble crusaders prevented the Egyptians from destroying their camp.

In late October, Al-Kamil sent messengers to the crusaders offering to restore Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Nazareth to them if they withdrew from Egypt. Although John and the secular lords were willing to accept the sultan's offer, Pelagius and the heads of the military orders resisted; they said that the Moslems could easily recapture the three towns. The crusaders ultimately refused the offer. Al-Kamil tried to send provisions to Damietta across their camp, but his men were captured on 3 November. Two days later, the crusaders stormed into Damietta and seized the town. Pelagius claimed it for the church, but he was forced to acknowledge John's right to administer it (at least temporarily) when John threatened to leave the crusaders' camp. According to John of Joinville

Jean de Joinville (, c. 1 May 1224 – 24 December 1317) was one of the great chroniclers of medieval France. He is most famous for writing the ''Life of Saint Louis'', a biography of Louis IX of France that chronicled the Seventh Crusade.' ...

, John seized one-third of Damietta's spoils; coins minted there during the following months bore his name. Al-Mu'azzam, emir of Damascus

This is a list of rulers of Damascus from ancient times to the present.

:''General context: History of Damascus''.

Aram Damascus

* Rezon I (c. 950 BC)

* Tabrimmon

*Ben-Hadad I (c. 885 BCE–c. 865 BC)

*Hadadezer (c. 865 BC–c. 842 BC)

*Hazael ( ...

and brother of al-Kamil, invaded the Kingdom of Jerusalem and pillaged Caesarea before the end of 1219.

John's father-in-law, Leo I of Armenia, died several months before the crusaders seized Damietta. He bequeathed his kingdom to his infant daughter, Isabella

Isabella may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Isabella (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Isabella (surname), including a list of people

Places

United States

* Isabella, Alabama, an unincorpor ...

. John and Raymond-Roupen of Antioch (Leo's nephew) questioned the will's legality, each demanding the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia for themselves. In a February 1220 letter, Pope Honorius declared John to be Leo's rightful heir. Saying that he wanted to assert his claim to Cilicia, John left Damietta for the Kingdom of Jerusalem around Easter 1220. Although Al-Mu'azzam's successful campaign the previous year also pressed John to leave Egypt, Jacques de Vitry and other Fifth Crusade chroniclers wrote that he deserted the crusader army.

Stephanie died shortly after John's arrival. Contemporary sources accused John of causing her sudden death, claiming that he severely beat her when he heard that she tried to poison his daughter Isabella

Isabella may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Isabella (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Isabella (surname), including a list of people

Places

United States

* Isabella, Alabama, an unincorpor ...

. Their only son died a few weeks later, ending John's claim to Cilicia. Soon after Pope Honorius learned about the deaths of Stephanie and her son, he declared Raymond-Roupen the lawful ruler of Cilicia and threatened John with excommunication if he fought for his late wife's inheritance.

John did not return to the crusaders in Egypt for several months. According to a letter from the prelates in the Holy Land to Philip II of France, lack of funds kept John from leaving his kingdom. Since his nephew Walter IV was approaching the age of majority, John surrendered the County of Brienne in 1221. During John's absence from Egypt, Al-Kamil again offered to restore the Holy Land to the Kingdom of Jerusalem in June 1221; Pelagius refused him. John returned to Egypt and rejoined the crusade on 6 July 1221 at the command of Pope Honorius.

The commanders of the crusader army decided to continue the invasion of Egypt, despite (according to Philip d'Aubigny) John's strong opposition. The crusaders approached Mansurah, but the Egyptians imposed a blockade on their camp. Outnumbered, Pelagius agreed to an eight-year truce with Al-Kamil in exchange for Damietta on 28 August. John was among the crusade leaders held hostage by Al-Kamil until the crusader army withdrew from Damietta on 8 September.

Negotiations

After the Fifth Crusade ended "in colossal and irremediable failure", John returned to his kingdom. Merchants fromGenoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

and Pisa soon attacked each other in Acre, destroying a significant portion of the town. According to a Genoese chronicle, John supported the Pisans and the Genoese left Acre for Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

.

John was the first king of Jerusalem to visit Europe, and had decided to seek aid from the Christian powers before he returned from Egypt. He also wanted to find a suitable husband for his daughter, to ensure the survival of Christian rule in the Holy Land. John appointed Odo of Montbéliard

Odo of Montbéliard (also known as Eudes) was a leading baron of the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem in the early 13th century. He often held the highest offices in the kingdom including ''bailli'' (viceroy) and constable (commander of the army).

...

as a ''bailli

A bailiff (french: bailli, ) was the king's administrative representative during the ''ancien régime'' in northern France, where the bailiff was responsible for the application of justice and control of the administration and local finances in h ...

'' to administer the Kingdom of Jerusalem in his absence.

He left for Italy in October 1222 to attend a conference about a new crusade. At John's request, Pope Honorius declared that all lands conquered during the crusade should be united with the Kingdom of Jerusalem. To plan the military campaign, the pope and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II met at

He left for Italy in October 1222 to attend a conference about a new crusade. At John's request, Pope Honorius declared that all lands conquered during the crusade should be united with the Kingdom of Jerusalem. To plan the military campaign, the pope and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II met at Ferentino

Ferentino is a town and ''comune'' in Italy, in the province of Frosinone, Lazio, southeast of Rome.

It is situated on a hill above sea level, in the Monti Ernici area.

History

''Ferentinum'' was a town of the Hernici; it was captured from the ...

in March 1223; John attended the meeting. He agreed to give his daughter in marriage to Frederick II after the emperor promised that he would allow John to rule the Kingdom of Jerusalem for the rest of his life.

John then went to France, although Philip II was annoyed at being excluded from the decision of Isabella's marriage. Matilda I, Countess of Nevers Matilda I, Countess of Nevers or Mathilde de Courtenay, or Mahaut de Courtenay, (1188–1257), was a ruling countess of Nevers, Auxerre and Tonnerre. She was the only daughter of Peter II of Courtenay and of Agnes of Nevers, born from the Capetia ...

, Erard II of Chacenay Erard II (died 16 June 1236) was the Sire de Chacenay (Chassenay) from 1190/1. He was the eldest son of Erard I of Chacenay and Mathilde de Donzy.

Life

In 1209 Erard, with the consent of his unnamed wife, confirmed a donation to Basse-Fontaine ...

, Albert, Abbot of Vauluisant and other local potentates asked John to intervene in their conflicts, indicating that he was esteemed in his homeland. John attended the funeral of Philip II at the Basilica of St Denis in July; Philip bequeathed more than 150,000 marks for the defence of the Holy Land. John then visited England, attempting to mediate a peace treaty between England and France after his return to France.

He made a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela

Santiago de Compostela is the capital of the autonomous community of Galicia, in northwestern Spain. The city has its origin in the shrine of Saint James the Great, now the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, as the destination of the Way of S ...

in March 1224. According to the '' Latin Chronicle of the Kings of Castile'', John went to the Kingdom of León to marry one of the elder daughters of Alfonso IX of León

Alfonso IX (15 August 117123 or 24 September 1230) was King of León and Galicia from the death of his father Ferdinand II in 1188 until his own death.

He took steps towards modernizing and democratizing his dominion and founded the Universit ...

( Sancha or Dulce) because Alfonso had promised him the kingdom "along with her". The marriage could jeopardize the claim of Sancha's and Dulce's half-brother, Ferdinand III of Castile

Ferdinand III ( es, Fernando, link=no; 1199/120130 May 1252), called the Saint (''el Santo''), was King of Castile from 1217 and King of León from 1230 as well as King of Galicia from 1231. He was the son of Alfonso IX of León and Berenguel ...

, to León. To protect her son's interests, Ferdinand's mother Berengaria of Castile

Berengaria ( Castilian: ''Berenguela''; nicknamed the Great (Castilian: la Grande); 1179 or 1180 – 8 November 1246) was reigning Queen of CastileThe full title was ''Regina Castelle et Toleti'' (Queen of Castille and Toledo). for a brief tim ...

decided to give her daughter (Berengaria of León

Berengaria of León (1204 – 12 April 1237) was the third wife but only empress consort of John of Brienne, Latin Emperor of Constantinople. She was a daughter of Alfonso IX of León and Berengaria of Castile. She was a younger sister of Ferdinan ...

) to John in marriage. Although modern historians do not unanimously accept the chronicle's account of John's plan to marry Sancha or Dulce, they agree that the queen of France (Blanche of Castile

Blanche of Castile ( es, Blanca de Castilla; 4 March 1188 – 27 November 1252) was Queen of France by marriage to Louis VIII. She acted as regent twice during the reign of her son, Louis IX: during his minority from 1226 until 1234, and during ...

, Berengaria of Castile's sister) played an important role in convincing John to marry her niece. The marriage of John and Berengaria of León was celebrated in Burgos

Burgos () is a city in Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the province of Burgos.

Burgos is situated in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, on the confluence of ...

in May 1224.

About three months later, he met Emperor Frederick's son Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

in Metz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand ...

and visited Henry's guardian, Engelbert, Archbishop of Cologne. From Germany John went to southern Italy, where he persuaded Pope Honorius to allow Emperor Frederick to postpone his crusade for two years. Frederick married John's daughter, Isabella (who had been crowned queen of Jerusalem), on 9 November 1225. John and Frederick's relationship became tense. According to a version of Ernoul's chronicle, John got into a disagreement with his new son-in-law because Frederick seduced a niece of Isabella who was her lady-in-waiting. In the other version of the chronicle John often "chastised and reproved" his son-in-law, who concluded that John wanted to seize the Kingdom of Sicily for his nephew Walter IV of Brienne and tried to murder John (who fled to Rome). Frederick declared that John had lost his claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem when Isabella married him; he styled himself king of Jerusalem for the first time in December 1225. Balian of Sidon

Balian I Grenier was the Count of Sidon and one of the most important lords of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from 1202 to 1241. He succeeded his father Renaud. His mother was Helvis, a daughter of Balian of Ibelin. He was a powerful and important re ...

, Simon of Maugastel, Archbishop of Tyre, and the other Jerusalemite lords who had escorted Isabella to Italy acknowledged Frederick as their lawful king.

Papal service

Pope Honorius did not accept Frederick's unilateral act, and continued to regard John as the rightful king of Jerusalem. In an attempt to take advantage of the revived Lombard League (an alliance of northern Italian towns) against Frederick II, John went toBologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

. According to a version of Ernoul's chronicle, he declined an offer by the Lombard League representatives to elect him their king. Even though this account was fabricated, John remained in Bologna for over six months. The dying Pope Honorius appointed John rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of a Patrimony of Saint Peter

The Patrimony of Saint Peter ( la, Patrimonium Sancti Petri) originally designated the landed possessions and revenues of various kinds that belonged to the apostolic Holy See (the Pope) i.e. the "Church of Saint Peter" in Rome, by virtue of the ap ...

in Tuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

(part of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

) on 27 January 1227, and urged Frederick II to restore him to the throne of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Honorius' successor, Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX ( la, Gregorius IX; born Ugolino di Conti; c. 1145 or before 1170 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decre ...

, confirmed John's position in the Papal States on 5 April and ordered the citizens of Perugia

Perugia (, , ; lat, Perusia) is the capital city of Umbria in central Italy, crossed by the River Tiber, and of the province of Perugia.

The city is located about north of Rome and southeast of Florence. It covers a high hilltop and pa ...

to elect him their '' podestà''.

Gregory excommunicated Frederick II on 29 September 1227, accusing him of breaking his oath to lead a crusade to the Holy Land; the emperor had dispatched two fleets to Syria, but a plague forced them to return. His wife Isabella died after giving birth to a son, Conrad, in May 1228. Frederick continued to consider himself king of Jerusalem, in accordance with the precedent set by John during Isabella's minority.

The imperial army under the command of Rainald of Urslingen invaded the Papal States in October 1228, beginning the so-called War of the Keys

The War of the Keys (1228–1230) was the first military conflict between Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, and the Papacy. Fighting took place in central and southern Italy. The Papacy made strong gains at first, securing the Papal States and in ...

. Although John defeated the invaders in a series of battles, it took a counter-invasion by another papal army in southern Italy to drive Rainald back to Sulmona

Sulmona ( nap, label= Abruzzese, Sulmóne; la, Sulmo; grc, Σουλμῶν, Soulmôn) is a city and ''comune'' of the province of L'Aquila in Abruzzo, Italy. It is located in the Valle Peligna, a plain once occupied by a lake that disappeared in ...

. John laid a siege before returning to Perugia in early 1229 to conclude negotiations with envoys of the Latin Empire of Constantinople

The Latin Empire, also referred to as the Latin Empire of Constantinople, was a feudal Crusader state founded by the leaders of the Fourth Crusade on lands captured from the Byzantine Empire. The Latin Empire was intended to replace the Byzant ...

, who were offering him the imperial crown.

Emperor of Constantinople

Election

The Latin Emperor of Constantinople, Robert I, died in January 1228. His brother Baldwin II succeeded him, but a regent was needed to rule the Latin Empire since Baldwin was ten years old.

The Latin Emperor of Constantinople, Robert I, died in January 1228. His brother Baldwin II succeeded him, but a regent was needed to rule the Latin Empire since Baldwin was ten years old. Ivan Asen II of Bulgaria

Ivan Asen II, also known as John Asen II ( bg, Иван Асен II, ; 1190s – May/June 1241), was Emperor (Tsar) of Bulgaria from 1218 to 1241. He was still a child when his father Ivan Asen I one of the founders of the Second Bulgarian Empi ...

was willing to accept the regency, but the barons of the Latin Empire suspected that he wanted to unite the Latin Empire with Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

. They offered the imperial crown instead to John, an ally of the Holy See.

After months of negotiation, John and the envoys from the Latin Empire signed a treaty in Perugia which was confirmed by Pope Gregory on 9 April 1229. John was elected emperor of the Latin Empire for life as senior co-ruler with Baldwin II, who married John's daughter Marie

Marie may refer to:

People Name

* Marie (given name)

* Marie (Japanese given name)

* Marie (murder victim), girl who was killed in Florida after being pushed in front of a moving vehicle in 1973

* Marie (died 1759), an enslaved Cree person in Tr ...

. The treaty also prescribed that although Baldwin would rule the Latin lands in Asia Minor when he was 20 years old, he would become sole emperor only after John's death. John also stipulated that his sons would inherit Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

and Macedonia, but the two regions still belonged to Emperor of Thessalonica

The Empire of Thessalonica is a historiographic term used by some modern scholarse.g. ,, , . to refer to the short-lived Byzantine Greek state centred on the city of Thessalonica between 1224 and 1246 (''sensu stricto'' until 1242) and ruled by ...

Theodore Doukas.

After signing the treaty, John returned to Sulmona. According to the contemporary Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris, also known as Matthew of Paris ( la, Matthæus Parisiensis, lit=Matthew the Parisian; c. 1200 – 1259), was an English Benedictine monk, chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts and cartographer, based at St Albans Abbey ...

, he allowed his soldiers to plunder nearby monasteries to obtain money. John lifted the siege of Sulmona in early 1229 to join Cardinal Pelagius, who launched a campaign against Capua

Capua ( , ) is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Caserta, in the region of Campania, southern Italy, situated north of Naples, on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain.

History

Ancient era

The name of Capua comes from the Etrus ...

. Frederick II (who had crowned himself king of Jerusalem in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre) returned to Italy, forcing the papal troops to withdraw.

John went to France to recruit warriors to accompany him to Constantinople. Pope Gregory did not proclaim John's expedition to the Latin Empire a crusade, but promised papal privileges granted to crusaders to those who joined him. During his stay in France, John was again an intermediary between local potentates and signed a peace treaty between Louis IX of France and Hugh X of Lusignan

Hugh X de Lusignan, Hugh V of La Marche or Hugh I of Angoulême (c. 1183 – c. 5 June 1249, Angoulême) was Seigneur de Lusignan and Count of La Marche in November 1219 and was Count of Angoulême by marriage. He was the son of Hugh IX ...

. He returned to Italy in late 1230. John's envoys signed a treaty with Jacopo Tiepolo

Jacopo Tiepolo (died 19 July 1249), also known as Giacomo Tiepolo, was Doge of Venice from 1229 to 1249. He had previously served as the first Venetian Duke of Crete, and two terms as Podestà of Constantinople (1218-1220 and 1224-1227). During ...

, Doge of Venice

The Doge of Venice ( ; vec, Doxe de Venexia ; it, Doge di Venezia ; all derived from Latin ', "military leader"), sometimes translated as Duke (compare the Italian '), was the chief magistrate and leader of the Republic of Venice between 726 ...

, who agreed to transport him and his retinue of 500 knights and 5,000 commoners to Constantinople in return for John's confirmation of Venetian possessions and privileges in the Latin Empire. Shortly after John left for Constantinople in August, Pope Gregory acknowledged Frederick II's claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Rule

John was crowned emperor inHagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia ( 'Holy Wisdom'; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque ( tr, Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi), is a mosque and major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The cathedral was originally built as a Greek Ortho ...

in autumn 1231; by then, his territory was limited to Constantinople and its vicinity. The Venetians urged him to wage war against John III Vatatzes, Emperor of Nicaea

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as le ...

, who supported a rebellion against their rule in Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

. According to Philippe Mouskes

Philippe Mouskes (before 1220 – 24 February 1282) was the author of a rhymed chronicle that draws on the history of the Franks and France, from the origins until 1242.

Biography

According to Barthelemy-Charles Dumortier, Philippe Mouskes bel ...

' ''Rhymed Chronicle'', John could make "neither war nor peace"; because he did not invade the Empire of Nicaea, most French knights who accompanied him to Constantinople returned home after his coronation. To strengthen the Latin Empire's financial position, Geoffrey II of Achaea (John's most powerful vassal) gave him an annual subsidy of 30,000 '' hyperpyra'' after his coronation.

Taking advantage of John III Vatatzes' invasion of Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

, John launched a military expedition across the Bosphorus against the Empire of Nicaea in 1233. His three-to-four-month campaign "achieved little, or nothing"; the Latins only seized Pegai, now Biga

Biga may refer to:

Places

* Biga, Çanakkale, a town and district of Çanakkale Province in Turkey

* Sanjak of Biga, an Ottoman province

* Biga Çayı, a river in Çanakkale Province

* Biga Peninsula, a peninsula in Turkey, in the northwest par ...

in Turkey. With John's approval, two Franciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

and two Dominican friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the ...

s wanted to mediate a truce between the Latin Empire and Nicaea in 1234 but it was never signed. In a letter describing their negotiations, the friars described John as a "pauper" abandoned by his mercenaries.

John III Vatatzes and Ivan Asen II concluded a treaty dividing the Latin Empire in early 1235. Vatatzes soon seized the last outposts of the empire in Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

and Gallipoli, and Asen occupied the Latin territories in Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

. Constantinople was besieged in an effort to persuade the defenders to gather in one place, enabling an invasion elsewhere. Although the besiegers outnumbered the defenders, John repelled all attacks on the town's walls. Mouskes compared him to Hector

In Greek mythology, Hector (; grc, Ἕκτωρ, Hektōr, label=none, ) is a character in Homer's Iliad. He was a Trojan prince and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. Hector led the Trojans and their allies in the defense o ...

, Roland, Ogier the Dane

Ogier the Dane (french: ; da, ) is a legendary paladin of Charlemagne who appears in many Old French '' chansons de geste''. In particular, he features as the protagonist in ''La Chevalerie Ogier'' (ca. 1220), which belongs to the ''Geste de D ...

and Judas Maccabeus in his ''Rhymed Chronicle'', emphasizing his bravery.

A Venetian fleet forced Vatatzes' naval forces to withdraw, but after the Venetians departed for home the Greeks and Bulgarians besieged Constantinople again in November 1235. John sent letters to European monarchs and the pope, pleading for assistance. Since the survival of the Latin Empire was in jeopardy, Pope Gregory urged the crusaders to defend Constantinople instead of the Holy Land. A combined naval force from Venice, Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, Pisa and Geoffrey II of Achaea broke through the blockade. Asen soon abandoned his alliance with Vatatzes, who was forced to lift the siege in 1236.

Death

According to three 13th-century authors (Matthew Paris, Salimbene di Adam andBernard of Besse Bernard of Besse was a French Friar Minor and chronicler.

He was a native of Aquitaine, with date of birth uncertain; he belonged to the custody of Cahors and was secretary to St. Bonaventure. He took up the pen after the Seraphic Doctor, he tell ...

), John became a Franciscan friar before his death. They agree that John's declining health contributed to his conversion, but Bernard also described a recurring vision of an old man urging the emperor to join the Franciscans. Most 13th-century sources suggest that John died between 19 and 23 March 1237, the only Latin emperor to die in Constantinople.

According to the ''Tales of the Minstrel of Reims'', he was buried in Hagia Sophia. Perry wrote that John, who died as a Franciscan friar, may have been buried in the Franciscan church dedicated to Saint Francis of Assisi which was built in Galata during his reign. In a third theory, proposed by Giuseppe Gerola

Giuseppe Gerola (2 April 1877 - 21 September 1938) was an Italian historian known for his involvement in monument restoration projects, his studies on Kingdom of Candia, Venetian Crete and his investigation of political, cultural and artistic topi ...

, a tomb decorated with the Latin Empire coat of arms in Assisi's Lower Basilica may have been built for John by Walter VI, Count of Brienne

Walter VI of Brienne (c. 1304 – 19 September 1356) was a French nobleman and crusader. He was the count of Brienne in France, the count of Conversano and Lecce in southern Italy and claimant to the Duchy of Athens in Frankish Greece.

Lif ...

.

Family

John's first wife ( Maria the Marquise, born 1191) was the only child ofIsabella I of Jerusalem

Isabella I (1172 – 5 April 1205) was reigning Queen of Jerusalem from 1190 to her death. She was the daughter of Amalric I of Jerusalem and his second wife Maria Comnena, a Byzantine princess. Her half-brother, Baldwin IV of Jerusalem, eng ...

and her second husband, Conrad of Montferrat

Conrad of Montferrat ( Italian: ''Corrado del Monferrato''; Piedmontese: ''Conrà ëd Monfrà'') (died 28 April 1192) was a nobleman, one of the major participants in the Third Crusade. He was the ''de facto'' King of Jerusalem (as Conrad I) by ...

. Maria inherited Jerusalem from her mother in 1205. John and Maria's only child, Isabella

Isabella may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Isabella (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Isabella (surname), including a list of people

Places

United States

* Isabella, Alabama, an unincorpor ...

(also known as Yolanda), was born in late 1212.

Stephanie of Armenia became John's second wife in 1214. She was the only daughter of Leo II of Armenia and his first wife, Isabelle (niece of Sibylle, the third wife of Bohemond III of Antioch

Bohemond III of Antioch, also known as Bohemond the Child or the Stammerer (french: Bohémond le Bambe/le Baube; 1148–1201), was Prince of Antioch from 1163 to 1201. He was the elder son of Constance of Antioch and her first husband, Raymond o ...

). Stephanie gave birth to a son in 1220, but she and her son died that year.

John married his third wife, Berengaria of León

Berengaria of León (1204 – 12 April 1237) was the third wife but only empress consort of John of Brienne, Latin Emperor of Constantinople. She was a daughter of Alfonso IX of León and Berengaria of Castile. She was a younger sister of Ferdinan ...

, in 1224; she was born around 1204 to Alfonso IX of León

Alfonso IX (15 August 117123 or 24 September 1230) was King of León and Galicia from the death of his father Ferdinand II in 1188 until his own death.

He took steps towards modernizing and democratizing his dominion and founded the Universit ...

and Berengaria of Castile

Berengaria ( Castilian: ''Berenguela''; nicknamed the Great (Castilian: la Grande); 1179 or 1180 – 8 November 1246) was reigning Queen of CastileThe full title was ''Regina Castelle et Toleti'' (Queen of Castille and Toledo). for a brief tim ...

. John and Berengaria's first child, Marie

Marie may refer to:

People Name

* Marie (given name)

* Marie (Japanese given name)

* Marie (murder victim), girl who was killed in Florida after being pushed in front of a moving vehicle in 1973

* Marie (died 1759), an enslaved Cree person in Tr ...

, was born in 1224. Their first son, Alphonse, was born during the late 1220s. Berengaria's cousin, Louis IX of France, made him Grand Chamberlain of France

The Grand Chamberlain of France (french: Grand Chambellan de France) was one of the Great Officers of the Crown of France, a member of the '' Maison du Roi'' ("King's Household"), and one of the Great Offices of the Maison du Roi during the Anc ...

and he acquired the County of Eu in France with his marriage. John's second son, Louis Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis ( ...

, was born around 1230. His youngest son, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, who was born in the early 1230s, was Grand Butler of France The Grand Butler of France (french: Grand bouteiller de France) was one of the great offices of state in France, existing between the Middle Ages and the Revolution of 1789. Originally responsible for the maintenance of the Royal vineyards, and prov ...

.

References

Sources

Primary sources

* ''George Akropolites: The History'' (Translated with an Introduction and Commentary by Ruth Mackrides) (2007). Oxford University Press. .Secondary sources

* * * * * * *External links

* (shows John's alleged tomb in the Lower Basilica in Assisi) * , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:John of Brienne 1170s births 1237 deaths 13th-century Latin Emperors of Constantinople 13th-century kings of Jerusalem Remarried royal consorts Kings of Jerusalem Jure uxoris kings French Franciscans Christians of the Fourth Crusade Christians of the Fifth Crusade House of Brienne 13th-century viceregal rulers Sicilian School poets