John Kourkouas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Kourkouas ( gr, Ἰωάννης Κουρκούας, Ioannes Kourkouas, ), also transliterated as Kurkuas or Curcuas, was one of the most important generals of the

Little is known about John's early life. His father was a wealthy official in the imperial palace, but no details are known about his life, nor is his name recorded (although it was likely Romanos). John himself was born at Dokeia (now

Little is known about John's early life. His father was a wealthy official in the imperial palace, but no details are known about his life, nor is his name recorded (although it was likely Romanos). John himself was born at Dokeia (now

In 927–928, Kourkouas launched a large raid into Arab-controlled

In 927–928, Kourkouas launched a large raid into Arab-controlled

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. His success in battles against the Muslim states in the East reversed the course of the centuries-long Arab–Byzantine wars

The Arab–Byzantine wars were a series of wars between a number of Muslim Arab dynasties and the Byzantine Empire between the 7th and 11th centuries AD. Conflict started during the initial Muslim conquests, under the expansionist Rashidun an ...

and set the stage for Byzantium's eastern conquests later in the century.

Kourkouas belonged to a family of Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian Diaspora, Armenian communities across the ...

descent that produced several notable Byzantine generals. As commander of an imperial bodyguard regiment, Kourkouas was among the chief supporters of Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

Romanos I Lekapenos

Romanos I Lekapenos ( el, Ρωμανός Λεκαπηνός; 870 – 15 June 948), Latinized as Romanus I Lecapenus, was Byzantine emperor from 920 until his deposition in 944, serving as regent for the infant Constantine VII.

Origin

Romanos ...

() and facilitated the latter's rise to the throne. In 923, Kourkouas was appointed commander-in-chief of the Byzantine armies along the eastern frontier, facing the Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

and the semi-autonomous Muslim border emirates. He kept this post for more than twenty years, overseeing decisive Byzantine military successes that altered the strategic balance in the region.

During the 9th century, Byzantium had gradually recovered its strength and internal stability while the Caliphate had become increasingly impotent and fractured. Under Kourkouas's leadership, the Byzantine armies advanced deep into Muslim territory for the first time in almost three centuries, expanding the imperial border. The emirates of Melitene and Qaliqala

Erzurum (; ) is a city in eastern Anatolia, Turkey. It is the largest city and capital of Erzurum Province and is 1,900 meters (6,233 feet) above sea level. Erzurum had a population of 367,250 in 2010.

The city uses the double-headed eagle as ...

were conquered, extending Byzantine control to the upper Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

and over western Armenia

Western Armenia (Western Armenian: Արեւմտեան Հայաստան, ''Arevmdian Hayasdan'') is a term to refer to the eastern parts of Turkey (formerly the Ottoman Empire) that are part of the historical homeland of the Armenians. Weste ...

. The remaining Iberian and Armenian princes became Byzantine vassals. Kourkouas also played a role in the defeat of a major Rus' raid in 941 and recovered the Mandylion

According to Christian tradition, the Image of Edessa was a holy relic consisting of a square or rectangle of cloth upon which a miraculous image of the face of Jesus had been imprinted—the first icon ("image"). The image is also known as the M ...

of Edessa

Edessa (; grc, Ἔδεσσα, Édessa) was an ancient city (''polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, founded during the Hellenistic period by King Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Seleucid Empire. It later became capital of the Kingdom of Osroene ...

, an important and holy relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains of a saint or the personal effects of the saint or venerated person preserved for purposes of veneration as a tangi ...

believed to depict the face of Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

. He was dismissed in 944 as a result of the machinations of Romanos Lekapenos's sons but restored to favour by Emperor Constantine VII (), serving as imperial ambassador in 946. His subsequent fate is unknown.

Biography

Early life and career

John was ascion

Scion may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

*Scion, a playable class in the game '' Path of Exile'' (2013)

*Atlantean Scion, a device in the ''Tomb Raider'' video game series

*Scions, an alien race in the video game ''B ...

of the Armenian Kourkouas The Kourkouas or Curcuas ( grc-x-medieval, Κουρκούας, from , ''Gurgen'') family was one of the many nakharar families from Armenia that migrated to the Byzantine Empire during the period of Arab rule over Armenia (7th–9th centuries). The ...

family—a Hellenized

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in th ...

form of their original surname, Gurgen ( hy, Գուրգեն, link=no)—which had risen to prominence in Byzantine service in the 9th century and established itself as one of the great families of the Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

n land-holding military aristocracy (the so-called "").. John's namesake grandfather had been a commander of the elite regiment () under Emperor Basil I

Basil I, called the Macedonian ( el, Βασίλειος ὁ Μακεδών, ''Basíleios ō Makedṓn'', 811 – 29 August 886), was a Byzantine Emperor who reigned from 867 to 886. Born a lowly peasant in the theme of Macedonia, he rose in the ...

(); John's brother Theophilos became a senior general, as did John's own son, Romanos, and his great-nephew (Theophilos' grandson), John Tzimiskes

John I Tzimiskes (; 925 – 10 January 976) was the senior Byzantine emperor from 969 to 976. An intuitive and successful general, he strengthened the Empire and expanded its borders during his short reign.

Background

John I Tzimiskes ...

. His wife, Maria, is known only from a collection of miracles of the Pege Monastery.

Little is known about John's early life. His father was a wealthy official in the imperial palace, but no details are known about his life, nor is his name recorded (although it was likely Romanos). John himself was born at Dokeia (now

Little is known about John's early life. His father was a wealthy official in the imperial palace, but no details are known about his life, nor is his name recorded (although it was likely Romanos). John himself was born at Dokeia (now Tokat

Tokat is the capital city of Tokat Province of Turkey in the mid-Black Sea region of Anatolia. It is located at the confluence of the Tokat River (Tokat Suyu) with the Yeşilırmak. In the 2018 census, the city of Tokat had a population of 155,00 ...

), in the region of Darbidos in the Armeniac Theme

The Armeniac Theme ( el, , ''Armeniakoi hema'), more properly the Theme of the Armeniacs (Greek: , ''thema Armeniakōi'') was a Byzantine theme (a military-civilian province) located in northeastern Asia Minor (modern Turkey).

History

The Armen ...

, and was educated by one of his relatives, the metropolitan bishop

In Christian churches with episcopal polity, the rank of metropolitan bishop, or simply metropolitan (alternative obsolete form: metropolite), pertains to the diocesan bishop or archbishop of a metropolis.

Originally, the term referred to the b ...

of Gangra, Christopher. In the late regency of Empress Zoe Karbonopsina

Zoe Karbonopsina, also Karvounopsina or Carbonopsina, ( el, Ζωὴ Καρβωνοψίνα, translit=Zōē Karbōnopsina), was an empress and regent of the Byzantine empire. She was the fourth spouse of the Byzantine Emperor Leo VI the Wise and th ...

(914–919) for her infant son Constantine VII (), Kourkouas was appointed as the commander of the palace guard regiment, probably through the machinations of the fellow Armenian, admiral Romanos Lekapenos

Romanos I Lekapenos ( el, Ρωμανός Λεκαπηνός; 870 – 15 June 948), Latinized as Romanus I Lecapenus, was Byzantine emperor from 920 until his deposition in 944, serving as regent for the infant Constantine VII.

Origin

Romanos ...

, as part of the latter's drive for the throne. In this capacity, Kourkouas arrested several high officials who opposed Lekapenos's rise to power, opening the road to the appointment of Lekapenos as regent in place of Zoe in 919. Lekapenos gradually assumed more powers until he was crowned senior emperor in December 920. As a reward for his support, in , Romanos Lekapenos promoted Kourkouas to the post of Domestic of the Schools

The office of the Domestic of the Schools ( gr, δομέστικος τῶν σχολῶν, domestikos tōn scholōn) was a senior military post of the Byzantine Empire, extant from the 8th century until at least the early 14th century. Originally ...

, in effect commander-in-chief of all the imperial armies in Anatolia. According to the chronicle of Theophanes Continuatus

''Theophanes Continuatus'' ( el, συνεχισταί Θεοφάνους) or ''Scriptores post Theophanem'' (, "those after Theophanes") is the Latin name commonly applied to a collection of historical writings preserved in the 11th-century Vat. g ...

, Kourkouas held this post for an unparalleled continuous term of 22 years and seven months.

At this time, and following the disastrous Battle of Acheloos

The Battle of Achelous or Acheloos ( bg, Битката при Ахелой, el, Μάχη του Αχελώου), also known as the Battle of Anchialus,Stephenson (2004), p. 23 took place on 20 August 917, on the Achelous river near the Bulga ...

in 917, the Byzantines were mostly occupied in the Balkans in a protracted conflict against Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

. Hence, Kourkouas's first task as Domestic of the East was the suppression of the revolt of Bardas Boilas, the governor () of Chaldia, a strategically important area on the Empire's northeastern Anatolian frontier. This was quickly achieved and his brother, Theophilos Kourkouas, replaced Boilas as governor of Chaldia. As commander of this northernmost sector of the eastern frontier, Theophilos proved a competent soldier and gave valuable assistance to his brother's campaigns.

First submission of Melitene, campaigns into Armenia

Following theMuslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

of the 7th century, the Arab–Byzantine conflict had featured constant raids and counter-raids along a relatively static border roughly defined by the line of the Taurus

Taurus is Latin for 'bull' and may refer to:

* Taurus (astrology), the astrological sign

* Taurus (constellation), one of the constellations of the zodiac

* Taurus (mythology), one of two Greek mythological characters named Taurus

* '' Bos tauru ...

and Anti-Taurus Mountains. Until the 860s, superior Muslim armies had placed the Byzantines on the defensive. Only after 863, with the victory in the Battle of Lalakaon

The Battle of Lalakaon ( gr, Μάχη τοῦ Λαλακάοντος), or Battle of Poson or Porson (), was fought in 863 between the Byzantine Empire and an invading Arab army in Paphlagonia (modern northern Turkey). The Byzantine army was led ...

, did the Byzantines gradually regain some lost ground against the Muslims, launching ever-deeper raids into Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

and Upper Mesopotamia

Upper Mesopotamia is the name used for the Upland and lowland, uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, ...

and annexing the Paulician

Paulicianism ( Classical Armenian: Պաւղիկեաններ, ; grc, Παυλικιανοί, "The followers of Paul"; Arab sources: ''Baylakānī'', ''al Bayāliqa'' )Nersessian, Vrej (1998). The Tondrakian Movement: Religious Movements in the ...

state around Tephrike (now Divriği

Divriği (formerly Tephrike, Greek: Τεφρική) is a small town and district of Sivas Province of Turkey. The town lies on gentle slope on the south bank of the Çaltısuyu river, a tributary of the Karasu river. The Great Mosque and Hospit ...

). Furthermore, according to historian Mark Whittow, "by 912 the Arabs had been pinned back behind the Taurus and Anti-Taurus", encouraging the Armenians to switch their allegiance from the Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

to the Empire, in whose service they entered in increasing numbers. The revival of Byzantine power was further facilitated by the progressive decline of the Abbasid Caliphate itself, particularly under al-Muqtadir (), when the central government faced several revolts. In the periphery of the Caliphate, the weakening of central control allowed the emergence of semi-autonomous local dynasties. In addition, after the death of the Bulgarian Tsar Simeon

Simeon () is a given name, from the Hebrew (Biblical ''Šimʿon'', Tiberian ''Šimʿôn''), usually transliterated as Shimon. In Greek it is written Συμεών, hence the Latinized spelling Symeon.

Meaning

The name is derived from Simeon, so ...

in 927, a peace treaty with the Bulgarians allowed the Empire to shift attention and resources to the East.

By 925, Romanos Lekapenos felt himself strong enough to demand the payment of tribute from the Muslim cities on the western side of the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

. When they refused, in 926, Kourkouas led the army across the border. Aided by his brother Theophilos and an Armenian contingent under the of Lykandos

Lykandos or Lycandus ( el, Λυκανδός), known as Djahan in Armenian, was the name of a Byzantine fortress and military-civilian province (or " theme"), known as the Theme of Lykandos (θέμα Λυκανδοῦ), in the 10th–11th centuries. ...

, Melias

Melias ( el, Μελίας) or Mleh ( hy, Մլեհ, often ''Mleh-mec'', "Mleh the Great" in Armenian sources) was an Armenian prince who entered Byzantine service and became a distinguished general, founding the theme of Lykandos and participating ...

, Kourkouas targeted Melitene (modern Malatya

Malatya ( hy, Մալաթիա, translit=Malat'ya; Syro-Aramaic ܡܠܝܛܝܢܐ Malīṭīná; ku, Meletî; Ancient Greek: Μελιτηνή) is a large city in the Eastern Anatolia region of Turkey and the capital of Malatya Province. The city h ...

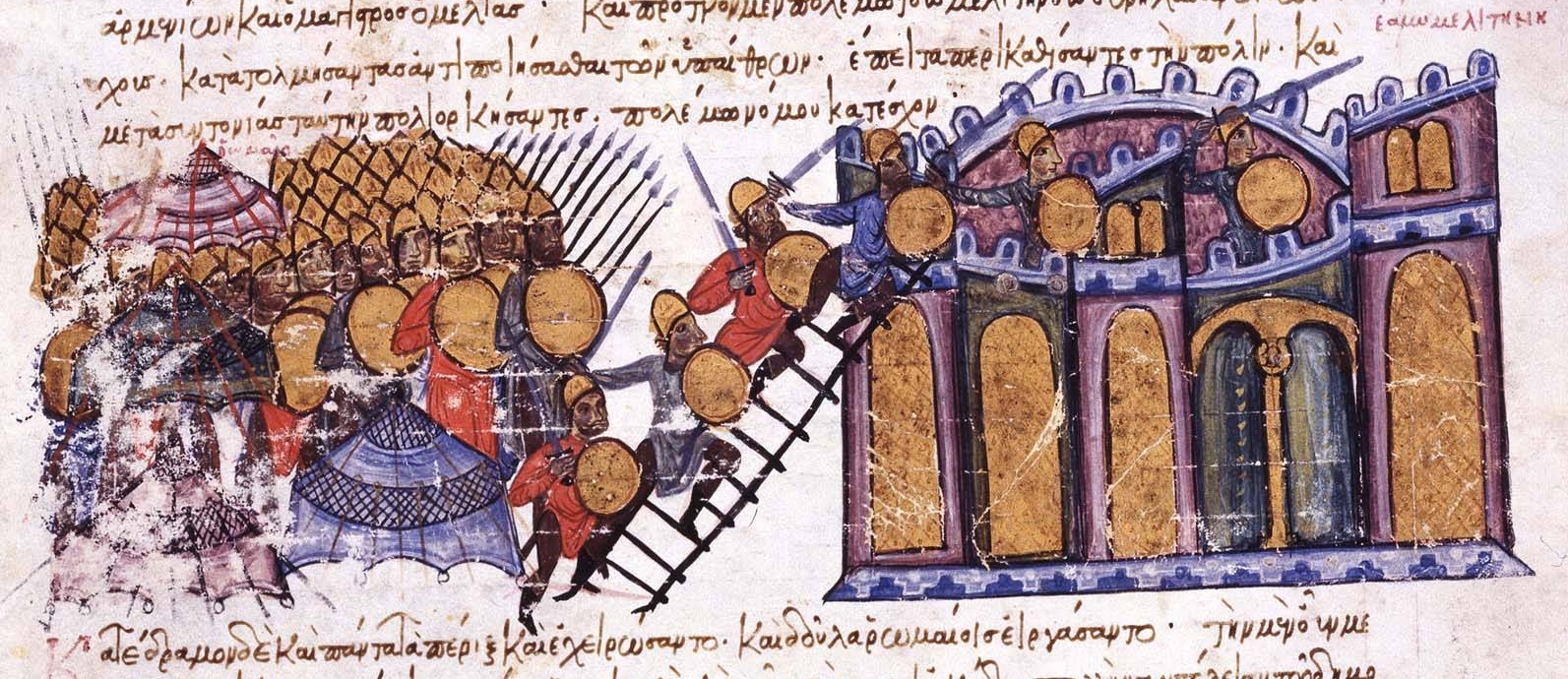

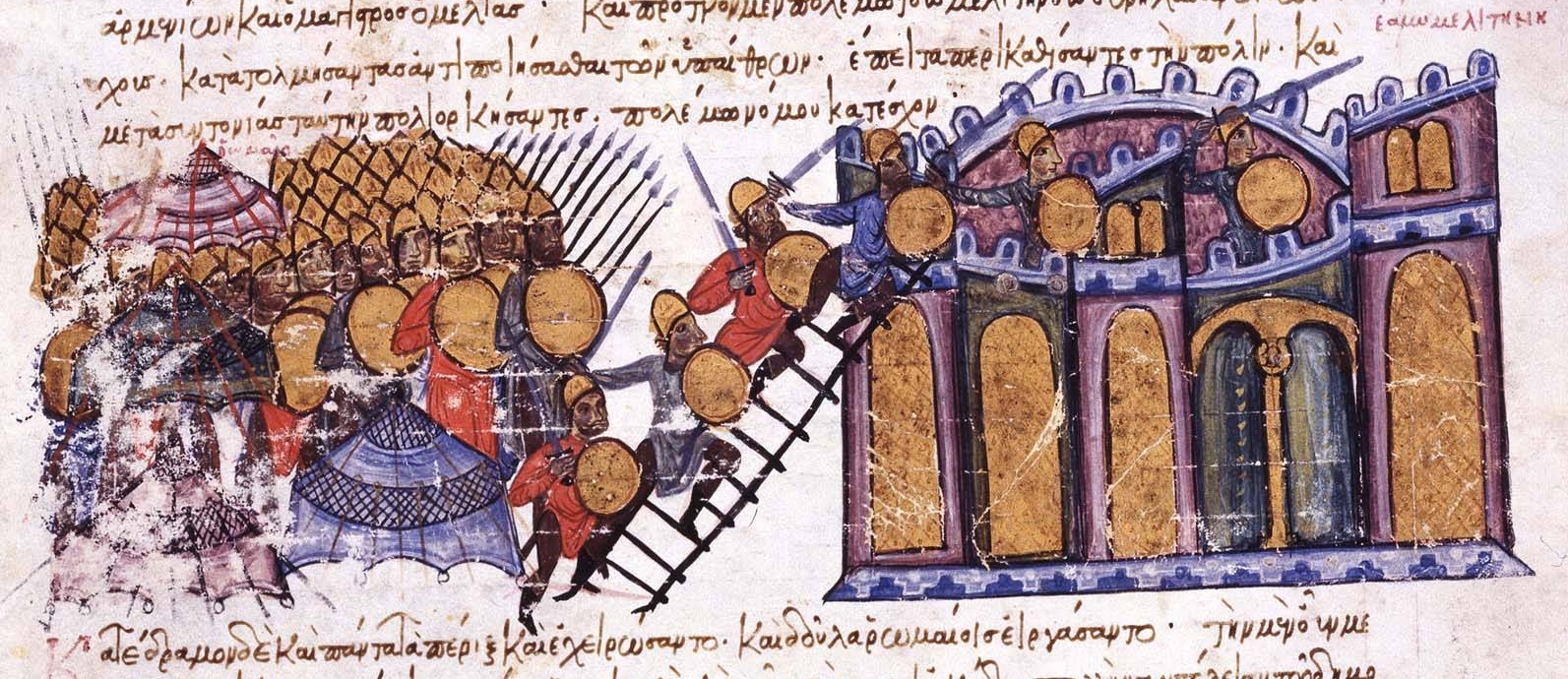

), the center of an emirate which had long been a thorn in Byzantium's side. The Byzantine army successfully stormed the lower city, and although the citadel held out, Kourkouas concluded a treaty by which the emir accepted tributary status.

In 927–928, Kourkouas launched a large raid into Arab-controlled

In 927–928, Kourkouas launched a large raid into Arab-controlled Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

. After taking Samosata (modern Samsat

Samsat ( ku, Samîsad), formerly Samosata ( grc, Σαμόσατα) is a small town in the Adıyaman Province of Turkey, situated on the upper Euphrates river. It is the seat of Samsat District.Dvin. An Arab counter-offensive forced them out of Samosata after only a few days, and Dvin, which was defended by the Sajid general Nasr al-Subuki, successfully withstood the Byzantine siege, until the mounting losses forced the Byzantines to abandon it. At the same time, Thamal, the emir of Tarsus, conducted successful raids into southern Anatolia and neutralized Ibn al-Dahhak, a local

The sources record no major Byzantine external campaigns for 932, as the Empire was preoccupied with two revolts in the

The sources record no major Byzantine external campaigns for 932, as the Empire was preoccupied with two revolts in the

Following this distraction, in January 942 Kourkouas launched a new campaign in the East, which lasted for three years. The first assault fell on the territory of

Following this distraction, in January 942 Kourkouas launched a new campaign in the East, which lasted for three years. The first assault fell on the territory of

Kurdish

Kurdish may refer to:

*Kurds or Kurdish people

*Kurdish languages

*Kurdish alphabets

*Kurdistan, the land of the Kurdish people which includes:

**Southern Kurdistan

**Eastern Kurdistan

**Northern Kurdistan

**Western Kurdistan

See also

* Kurd (dis ...

leader who supported the Byzantines. The Byzantines then turned toward the Kaysite

The Kaysite dynasty () was a Muslim Arab dynasty that ruled an emirate centered in Manzikert from c. 860 until 964. Their state was the most powerful Arab amirate in Armenia after the collapse of the ''ostikan''ate of Arminiya in the late 9t ...

emirate in the region of Lake Van

Lake Van ( tr, Van Gölü; hy, Վանա լիճ, translit=Vana lič̣; ku, Gola Wanê) is the largest lake in Turkey. It lies in the far east of Turkey, in the provinces of Van and Bitlis in the Armenian highlands. It is a saline soda lake ...

in southern Armenia. Kourkouas's troops plundered the region and took the towns of Khliat and Bitlis

Bitlis ( hy, Բաղեշ '; ku, Bidlîs; ota, بتليس) is a city in southeastern Turkey and the capital of Bitlis Province. The city is located at an elevation of 1,545 metres, 15 km from Lake Van, in the steep-sided valley of the Bitlis R ...

, where they are said to have replaced the mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...

's (pulpit) with a cross. The local Arabs appealed to the Caliph for aid in vain, prompting an exodus of Muslims from the region. This incursion, more than from the nearest imperial territory, was a far cry from the defensive-minded strategy Byzantium had followed during the previous centuries and highlighted the new capabilities of the imperial army. Nevertheless, famine in Anatolia and the exigencies of parallel campaigns in southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

weakened Kourkouas's forces. His army was defeated and driven back by Muflih, a former Sajid (slave-soldier) and governor of Adharbayjan.

In 930, Melias's attack on Samosata was heavily defeated; among other prominent officers, one of his sons was captured and sent to Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

. Later in the same year, John and his brother Theophilos besieged Theodosiopolis (modern Erzurum

Erzurum (; ) is a city in eastern Anatolia, Turkey. It is the largest city and capital of Erzurum Province and is 1,900 meters (6,233 feet) above sea level. Erzurum had a population of 367,250 in 2010.

The city uses the double-headed eagle as ...

), the capital of the emirate of Qaliqala. The campaign was complicated by the machinations of their ostensible allies, the Iberian rulers of Tao-Klarjeti Tao-Klarjeti may refer to:

* Tao-Klarjeti, part of Georgian historical region of Upper Kartli

* Kingdom of Tao-Klarjeti, AD 888 to 1008

{{set index article

Kingdom of Iberia

Historical regions of Georgia (country) ...

. Resenting the extension of direct Byzantine control adjacent to their own borders, the Iberians had already provided supplies to the besieged city. Once the city was invested, they vociferously demanded that the Byzantines hand over several captured towns, but when one of them, the fort of Mastaton, was surrendered, the Iberians promptly returned it to the Arabs. As Kourkouas needed to keep the Iberians placated and was aware that his conduct was being carefully observed by the Armenian princes, he did not react to this affront. After seven months of siege, Theodosiopolis fell in spring 931 and was transformed into a tributary vassal, while, according to Constantine VII's '' De Administrando Imperio'', all territory north of the river Araxes was given to the Iberian king David II. As in Melitene, the maintenance of Byzantine control over Theodosiopolis proved difficult and the population remained restive. In 939, it revolted and drove out the Byzantines, and Theophilos Kourkouas could not finally subdue the city until 949. It was then fully incorporated into the Empire and its Muslim population was expelled and replaced by Greek and Armenian settlers.

Final capture of Melitene

Following the death of EmirAbu Hafs Abu Hafs may refer to:

* Abu Hafs Umar al-Nasafi, a Muslim scholar of 11th/12th century

* Mohammed Atef (Abu Hafs al-Masri), past military chief of al-Qaeda

* Abu Hafs Umar al-Iqritishi, early ninth-century Andalusian pirate and founder of the Emir ...

, Melitene renounced its Byzantine allegiance. After attempts to take the city by storm or subterfuge failed, the Byzantines established a ring of fortresses on the hills around the plain of Melitene, and methodically ravaged the area. By early 931, the inhabitants of Melitene were forced to come to terms: they agreed to tributary status and even undertook to provide a military contingent to campaign alongside the Byzantines.

The other Muslim states were not idle, however: in March, the Byzantines were hit by three successive raids in Anatolia, organized by the Abbasid commander Mu'nis al-Muzaffar

Abū'l-Ḥasan Mu'nis al-Qushuri ( ar, ابوالحسن مؤنس ابوالحسن; 845/6–933), also commonly known by the surnames al-Muẓaffar (; ) and al-Khadim (; 'the Eunuch'), was the commander-in-chief of the Abbasid army from 908 to his ...

, while in August, a large raid led by Thamal of Tarsus penetrated as far as Ancyra

Ankara ( , ; ), historically known as Ancyra and Angora, is the list of national capitals, capital of Turkey. Located in the Central Anatolia Region, central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5.1 million in its urban center ...

and Amorium

Amorium was a city in Phrygia, Asia Minor which was founded in the Hellenistic period, flourished under the Byzantine Empire, and declined after the Arab sack of 838. It was situated on the Byzantine military road from Constantinople to Cil ...

and returned with prisoners worth 136,000 gold dinar

The gold dinar ( ar, ﺩﻳﻨﺎﺭ ذهبي) is an Islamic medieval gold coin first issued in AH 77 (696–697 CE) by Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan. The weight of the dinar is 1 mithqal ().

The word ''dinar'' comes from the La ...

s. During this time, the Byzantines were engaged in southern Armenia, aiding the ruler of Vaspurakan

Vaspurakan (, Western Armenian pronunciation: ''Vasbouragan'') was the eighth province of the ancient kingdom of Armenia, which later became an independent kingdom during the Middle Ages, centered on Lake Van. Located in what is now southeaster ...

, Gagik I, who had rallied the local Armenian princes and allied himself with the Byzantines against the emir of Adharbayjan. There they raided the Kaysite emirate and razed Khliat and Berkri

Muradiye ( ku, Bêgirî, hy, Բերկրի, translit=Berkri) is a town and district in the Van Province of Turkey.

History

The tenth-century Byzantine text '' De Administrando Imperio'' mentions "Perkri" belonging to King Ashot I Bagratuni at t ...

to the ground, before marching into Mesopotamia and capturing Samosata again. Gagik was unable to take advantage of this and capture Kaysite territory, however, as Muflih immediately raided his domains in retaliation. At this point, the Melitenians called upon the Hamdanid

The Hamdanid dynasty ( ar, الحمدانيون, al-Ḥamdāniyyūn) was a Twelver Shia Arab dynasty of Northern Mesopotamia and Syria (890–1004). They descended from the ancient Banu Taghlib Christian tribe of Mesopotamia and Eastern Ara ...

rulers of Mosul

Mosul ( ar, الموصل, al-Mawṣil, ku, مووسڵ, translit=Mûsil, Turkish: ''Musul'', syr, ܡܘܨܠ, Māwṣil) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. The city is considered the second large ...

for help. In response, the Hamdanid prince Sa'id ibn Hamdan

Sa'id ibn Hamdan () was an early member of the Hamdanid dynasty who served as provincial governor and military leader under the Abbasid Caliphate. He was the father of the celebrated poet Abu Firas al-Hamdani.

Biography

Sa'id was a son of the Hamd ...

attacked the Byzantines and drove them back: Samosata was abandoned, and in November 931, the Byzantine garrison withdrew from Melitene as well. Sa'id was, however, unable to remain in the area or to leave a sufficient garrison; once he left for Mosul, the Byzantines returned and resumed both the blockade of Melitene and their scorched-earth tactics.

The sources record no major Byzantine external campaigns for 932, as the Empire was preoccupied with two revolts in the

The sources record no major Byzantine external campaigns for 932, as the Empire was preoccupied with two revolts in the Opsician Theme

The Opsician Theme ( gr, θέμα Ὀψικίου, ''thema Opsikiou'') or simply Opsikion (Greek: , from la, Obsequium) was a Byzantine theme (a military-civilian province) located in northwestern Asia Minor (modern Turkey). Created from the imp ...

. In 933, Kourkouas renewed the attack against Melitene. Mu'nis al-Muzaffar sent forces to assist the beleaguered city, but in the resulting skirmishes, the Byzantines prevailed and took many prisoners and the Arab army returned home without relieving the city. In early 934, at the head of 50,000 men, Kourkouas again crossed the frontier and marched toward Melitene. The other Muslim states offered no help, preoccupied as they were with the turmoil following Caliph al-Qahir

Abu Mansur Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Mu'tadid ( ar, أبو المنصور محمد بن أحمد المعتضد, Abū al-Manṣūr Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Muʿtaḍid), usually known simply by his regnal title Al-Qahir bi'llah ( ar, القاهر � ...

's deposition. Kourkouas again took Samosata and besieged Melitene. Many of the city's inhabitants had abandoned it at the news of Kourkouas's approach and hunger eventually compelled the rest to surrender on 19 May 934. Wary of the city's previous rebellions, Kourkouas only allowed those inhabitants to remain who were Christians or agreed to convert to Christianity. Most did so, and he ordered the remainder expelled. Melitene was fully incorporated into the empire, and most of its fertile land was transformed into an imperial estate (). This was an unusual move, implemented by Romanos I to prevent the powerful Anatolian landed aristocracy from taking control of the province. It also served to increase direct imperial presence and control on the crucial new borderlands.

Rise of the Hamdanids

The fall of Melitene profoundly shocked the Muslim world: for the first time, a major Muslim city had fallen and been incorporated into the Byzantine Empire. Kourkouas followed this success by subduing parts of the district of Samosata in 936 and razing the city to the ground. Until 938, the East remained relatively calm. Historians suggest that the Byzantines were likely preoccupied with the full pacification of Melitene, and the Arab emirates, deprived of any potential support from the Caliphate, were reluctant to provoke them. With the decline of the Caliphate and its obvious inability to defend its border provinces, a new local dynasty, theHamdanids

The Hamdanid dynasty ( ar, الحمدانيون, al-Ḥamdāniyyūn) was a Twelver Shia Arab dynasty of Northern Mesopotamia and Syria (890–1004). They descended from the ancient Banu Taghlib Christian tribe of Mesopotamia and Eastern A ...

, emerged as the principal antagonists of Byzantium in northern Mesopotamia

Upper Mesopotamia is the name used for the uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, the region has been ...

and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

. They were led by al-Hasan, called ('Defender of the State'), and by his younger brother Ali, best known by his epithet

An epithet (, ), also byname, is a descriptive term (word or phrase) known for accompanying or occurring in place of a name and having entered common usage. It has various shades of meaning when applied to seemingly real or fictitious people, di ...

, ('Sword of the State'). In , the Arab tribe of Banu Habib, defeated by the rising Hamdanids, defected in its entirety to the Byzantines, converted to Christianity, and placed its 12,000 horsemen at the disposal of the Empire. They were settled along the western bank of the Euphrates and assigned to guard five new themes created there: Melitene, Charpezikion Charpezikion ( gr, Χαρπεζίκιον) was a Byzantine fortress and small province (theme) in the 10th century.

The fortress of Charpezikion is identified with Çarpezik Kalesi, east of the Euphrates River, while some earlier scholars identify ...

, Asmosaton (Arsamosata

Arsamosata (Middle Persian ''*Aršāmšād''; Old Persian ''*Ṛšāma-šiyāti-'', grc, Ἀρσαμόσατα, ) was an ancient and medieval city situated on the bank of the Murat River, near the present-day city of Elâzığ. It was founded in ...

), Derzene, and Chozanon.

The first Byzantine encounter with Sayf al-Dawla took place in 936, when he tried to relieve Samosata, but a revolt at home forced him to turn back. In another invasion in 938, however, he captured the fort of Charpete and defeated Kourkouas's advance guard, seizing a great amount of booty and forcing Kourkouas to withdraw. In the same year, a peace agreement was signed between Constantinople and the Caliphate. The negotiations were facilitated by the rising power of the Hamdanids, which caused anxiety to both sides. Despite the official peace with the Caliphate, ''ad hoc'' warfare continued between the Byzantines and the local Muslim rulers, now aided by the Hamdanids. The Byzantines attempted to besiege Theodosiopolis in 939, but the siege was abandoned at the news of the approach of Sayf al-Dawla's relief army.

By that time, the Byzantines had captured Arsamosata and additional strategically important locations in the mountains of southwest Armenia, posing a direct threat to the Muslim emirates around Lake Van. To reverse the situation, in 940 Sayf al-Dawla initiated a remarkable campaign: starting from Mayyafiriqin (Byzantine Martyropolis), he crossed the Bitlis

Bitlis ( hy, Բաղեշ '; ku, Bidlîs; ota, بتليس) is a city in southeastern Turkey and the capital of Bitlis Province. The city is located at an elevation of 1,545 metres, 15 km from Lake Van, in the steep-sided valley of the Bitlis R ...

pass into Armenia, where he seized several fortresses and accepted the submission of the local lords, both Muslim and Christian. He ravaged the Byzantine holdings around Theodosiopolis and raided as far as Koloneia, which he besieged until Kourkouas arrived with a relief army and forced him to withdraw. Sayf al-Dawla was not able to follow up on this effort: until 945, the Hamdanids were preoccupied with internal developments in the Caliphate and with fighting against their rivals in southern Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

and the Ikhshidids

The Ikhshidid dynasty (, ) was a Turkic mamluk dynasty who ruled Egypt and the Levant from 935 to 969. Muhammad ibn Tughj al-Ikhshid, a Turkic mamluk soldier, was appointed governor by the Abbasid Caliph al-Radi. The dynasty carried the Arabic t ...

in Syria.

Rus' raid of 941

The distraction by the Hamdanids proved fortunate for Byzantium. In early summer 941, as Kourkouas prepared to resume campaigning in the East, his attention was diverted by an unexpected event: the appearance of a Rus' fleet that raided the area around Constantinople itself. The Byzantine army and navy were absent from the capital, and the appearance of the Rus' fleet caused panic among the populace of Constantinople. While the navy and Kourkouas's army were recalled, a hastily assembled squadron of old ships armed withGreek Fire

Greek fire was an incendiary weapon used by the Eastern Roman Empire beginning . Used to set fire to enemy ships, it consisted of a combustible compound emitted by a flame-throwing weapon. Some historians believe it could be ignited on contact w ...

and placed under the Theophanes defeated the Rus' fleet on June 11, forcing it to abandon its course toward the city. The surviving Rus' landed on the shores of Bithynia

Bithynia (; Koine Greek: , ''Bithynía'') was an ancient region, kingdom and Roman province in the northwest of Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), adjoining the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus, and the Black Sea. It bordered Mysia to the southwest, Pa ...

and ravaged the defenseless countryside. The Bardas Phokas hastened to the area with whatever troops he could gather, contained the raiders, and awaited the arrival of Kourkouas's army. Finally, Kourkouas and his army appeared and fell upon the Rus', who had dispersed to plunder the countryside, killing many of them. The survivors retreated to their ships and tried to cross to Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

under the cover of night. During the crossing, the entire Byzantine navy

The Byzantine navy was the naval force of the East Roman or Byzantine Empire. Like the empire it served, it was a direct continuation from its Imperial Roman predecessor, but played a far greater role in the defence and survival of the state than ...

attacked and annihilated the Rus'.

Campaigns in Mesopotamia and recovery of the Mandylion

Following this distraction, in January 942 Kourkouas launched a new campaign in the East, which lasted for three years. The first assault fell on the territory of

Following this distraction, in January 942 Kourkouas launched a new campaign in the East, which lasted for three years. The first assault fell on the territory of Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

, which was thoroughly plundered: at the fall of the town of Hamus, near Aleppo, even Arab sources record the capture of 10–15,000 prisoners by the Byzantines. Despite a minor counter-raid by Thamal or one of his retainers from Tarsus in the summer, in autumn Kourkouas launched another major invasion. At the head of an exceptionally large army, some 80,000 men according to Arab sources, he crossed from allied Taron into northern Mesopotamia. Mayyafiriqin, Amida, Nisibis

Nusaybin (; '; ar, نُصَيْبِيْن, translit=Nuṣaybīn; syr, ܢܨܝܒܝܢ, translit=Nṣībīn), historically known as Nisibis () or Nesbin, is a city in Mardin Province, Turkey. The population of the city is 83,832 as of 2009 and is ...

, Dara

Dara is a given name used for both males and females, with more than one origin. Dara is found in the Bible's Old Testament Books of Chronicles. Dara �רעwas a descendant of Judah (son of Jacob). (The Bible. 1 Chronicles 2:6). Dara (also known ...

—places where no Byzantine army had trod since the days of Heraclius

Heraclius ( grc-gre, Ἡράκλειος, Hērákleios; c. 575 – 11 February 641), was List of Byzantine emperors, Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the Exa ...

300 years earlier—were stormed and ravaged. The real aim of these campaigns, however, was Edessa

Edessa (; grc, Ἔδεσσα, Édessa) was an ancient city (''polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, founded during the Hellenistic period by King Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Seleucid Empire. It later became capital of the Kingdom of Osroene ...

, the repository of the "Holy Mandylion

According to Christian tradition, the Image of Edessa was a holy relic consisting of a square or rectangle of cloth upon which a miraculous image of the face of Jesus had been imprinted—the first icon ("image"). The image is also known as the M ...

". This was a cloth believed to have been used by Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

to wipe his face, leaving an imprint of his features, and subsequently given to King Abgar V of Edessa

Abgar V (c. 1st century BC - c. AD 50), called Ukkāmā (meaning "the Black" in Syriac and other dialects of Aramaic),, syr, ܐܒܓܪ ܚܡܝܫܝܐ ܐܘܟܡܐ, ʾAḇgar Ḥmīšāyā ʾUkkāmā, hy, Աբգար Ե Եդեսացի, Abgar Hingeror ...

. To the Byzantines, especially after the end of the Iconoclasm period and the restoration of the veneration of images, it was a relic of profound religious significance. As a result, its capture would provide the Lekapenos regime with an enormous boost in popularity and legitimacy.

Kourkouas assailed Edessa every year from 942 onward and devastated its countryside, as he had done at Melitene. Finally, its emir agreed to a peace, swearing not to raise arms against Byzantium and to hand over the Mandylion in exchange for the return of 200 prisoners. The Mandylion was conveyed to Constantinople, where it arrived on August 15, 944, on the feast of the Dormition of the Theotokos

The Dormition of the Mother of God is a Great Feast of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Catholic Churches (except the East Syriac churches). It celebrates the "falling asleep" (death) of Mary the ''Theotokos'' ("Mother of ...

. A triumphal entry was staged for the venerated relic, which was then deposited in the Theotokos of the Pharos

The Church of the Virgin of the Pharos ( el, Θεοτόκος τοῦ Φάρου, ''Theotokos tou Pharou'') was a Byzantine chapel built in the southern part of the Great Palace of Constantinople, and named after the tower of the lighthouse (''pha ...

church, the palatine chapel of the Great Palace. As for Kourkouas, he concluded his campaign by sacking Bithra (modern Birecik

Birecik; ku, Bêrecûk is a town and district of Şanlıurfa Province of Turkey, on the Euphrates.

Built on a limestone cliff 400 ft. high on the left/east bank of the Euphrates, "at the upper part of a reach of that river, which runs near ...

) and Germanikeia (modern Kahramanmaraş).

Dismissal and rehabilitation

Despite this triumph, the downfall of Kourkouas, as well as of his friend and protector, Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos, was imminent. The two eldest surviving sons of Romanos I, co-emperorsStephen

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

and Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

, were jealous of Kourkouas and had in the past tried to undermine him, albeit without success. Following the success of Kourkouas in the East, Romanos I considered marrying his trusted general into the imperial family. Kourkouas's daughter Euphrosyne was to be wedded with the emperor's grandson, the future Romanos II

Romanos II Porphyrogenitus ( gr, Ρωμανός, 938 – 15 March 963) was Byzantine Emperor from 959 to 963. He succeeded his father Constantine VII at the age of twenty-one and died suddenly and mysteriously four years later. His son Bas ...

(), the son of his son-in-law and junior emperor Constantine VII. Although such a union would effectively cement the loyalty of the army, it would also strengthen the position of the legitimate Macedonian line, represented by Constantine VII, over the imperial claims of Romanos's own sons. Predictably, Stephen and Constantine opposed this decision and prevailed upon their father, who was by this time old and ill, to dismiss Kourkouas in the autumn of 944.

Kourkouas was replaced by a certain Pantherios, who was almost immediately defeated by Sayf al-Dawla in December while raiding near Aleppo. On 16 December, Romanos I himself was deposed by Stephen and Constantine and banished to a monastery on the island of Prote. A few weeks later, on 26 January, another coup removed the two young Lekapenoi from power and restored the sole imperial authority to Constantine VII. Kourkouas himself appears to have soon returned to imperial favour: Constantine provided the money for the repair of Kourkouas's palace after it was damaged by an earthquake, and in early 946, he is recorded as having been sent with the Kosmas to negotiate a prisoner exchange

A prisoner exchange or prisoner swap is a deal between opposing sides in a conflict to release prisoners: prisoners of war, spies, hostages, etc. Sometimes, dead bodies are involved in an exchange.

Geneva Conventions

Under the Geneva Convent ...

with the Arabs of Tarsus. Nothing further is known about him.

The fall of the Lekapenoi signalled the end of an era in terms of personalities, but Kourkouas's expansionist policy continued: he was succeeded as Domestic of the Schools by Bardas Phokas the Elder

Bardas Phokas ( el, ) (c. 878 – c. 968) was a notable Byzantine general in the first half of the 10th century, and father of Byzantine emperor Nikephoros II Phokas and the ''kouropalates'' Leo Phokas the Younger.

Bardas was the scion of the Ph ...

, followed by Nikephoros Phokas

Nikephoros II Phokas (; – 11 December 969), Latinized Nicephorus II Phocas, was Byzantine emperor from 963 to 969. His career, not uniformly successful in matters of statecraft or of war, nonetheless included brilliant military exploits whi ...

, who reigned as emperor in 963–969, and finally, by Kourkouas's own great-nephew, John Tzimiskes

John I Tzimiskes (; 925 – 10 January 976) was the senior Byzantine emperor from 969 to 976. An intuitive and successful general, he strengthened the Empire and expanded its borders during his short reign.

Background

John I Tzimiskes ...

, who reigned as emperor in 969–976. All of them expanded the Byzantine frontier in the East, recovering Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern coa ...

and northern Syria with Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

, and converting the Hamdanid emirate of Aleppo into a Byzantine protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

.

Assessment

Kourkouas ranks among the greatest military leaders Byzantium produced, a fact recognized by the Byzantines themselves. Later Byzantine chroniclers hailed him as the general who restored the imperial frontier to theEuphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

, In a contemporary eight-book history, written by a Manuel and now lost save for a short summary in Theophanes Continuatus

''Theophanes Continuatus'' ( el, συνεχισταί Θεοφάνους) or ''Scriptores post Theophanem'' (, "those after Theophanes") is the Latin name commonly applied to a collection of historical writings preserved in the 11th-century Vat. g ...

, he is acclaimed for having conquered a thousand cities, and described as "a second Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

or Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terri ...

".

The ground work for his successes had certainly been laid by others: Michael III

Michael III ( grc-gre, Μιχαήλ; 9 January 840 – 24 September 867), also known as Michael the Drunkard, was Byzantine Emperor from 842 to 867. Michael III was the third and traditionally last member of the Amorian (or Phrygian) dynasty. ...

, who broke the power of Melitene at Lalakaon; Basil I

Basil I, called the Macedonian ( el, Βασίλειος ὁ Μακεδών, ''Basíleios ō Makedṓn'', 811 – 29 August 886), was a Byzantine Emperor who reigned from 867 to 886. Born a lowly peasant in the theme of Macedonia, he rose in the ...

, who destroyed the Paulicians

Paulicianism (Classical Armenian: Պաւղիկեաններ, ; grc, Παυλικιανοί, "The followers of Paul"; Arab sources: ''Baylakānī'', ''al Bayāliqa'' )Nersessian, Vrej (1998). The Tondrakian Movement: Religious Movements in the ...

; Leo VI the Wise

Leo VI, called the Wise ( gr, Λέων ὁ Σοφός, Léōn ho Sophós, 19 September 866 – 11 May 912), was Byzantine Emperor from 886 to 912. The second ruler of the Macedonian dynasty (although his parentage is unclear), he was very well r ...

, who founded the vital theme of Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

; and Empress Zoe, who extended Byzantine influence again into Armenia and founded the theme of Lykandos. It was Kourkouas and his campaigns, however, that incontrovertibly changed the balance of power in the northern Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, securing the frontier provinces against Arab raids and turning Byzantium into an expansionist power. In the words of historian Steven Runciman

Sir James Cochran Stevenson Runciman ( – ), known as Steven Runciman, was an English historian best known for his three-volume ''A History of the Crusades'' (1951–54).

He was a strong admirer of the Byzantine Empire. His history's negative ...

, "a lesser general might ..have cleared the Empire of the Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

s and successfully defended its borders; but ourkouasdid more. He infused a new spirit into the imperial armies, and led them victoriously deep into the country of the infidels. The actual area of his conquests was not so very large; but they sufficed to reverse the age-old roles of Byzantium and the Arabs. Byzantium now was the aggressor... ohn Kourkouaswas the first of a line of great conquerors and as the first is worthy of high praise."

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Kourkouas, John 9th-century births 10th-century deaths 10th-century Byzantine people Byzantine generalsJohn

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

History of Malatya

Byzantine people of the Arab–Byzantine wars

Domestics of the Schools

Magistroi