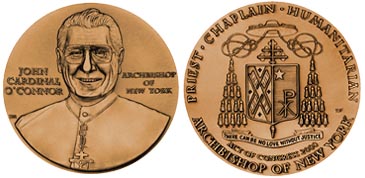

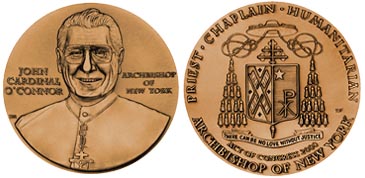

John Joseph Cardinal O'Connor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Joseph O'Connor (January 15, 1920 – May 3, 2000) was an

O'Connor attended public schools until his

O'Connor attended public schools until his

O'Connor was posthumously awarded the

O'Connor was posthumously awarded the

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

prelate

A prelate () is a high-ranking member of the Christian clergy who is an ordinary or who ranks in precedence with ordinaries. The word derives from the Latin , the past participle of , which means 'carry before', 'be set above or over' or 'pref ...

of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. He served as Archbishop of New York

The Archbishop of New York is the head of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, who is responsible for looking after its spiritual and administrative needs. As the archdiocese is the metropolitan bishop, metropolitan see of the ecclesiastic ...

from 1984 until his death in 2000, and was made a cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

in 1985. He previously served as a U.S. Navy chaplain (1952–1979, including four years as Chief

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the boa ...

), auxiliary bishop of the Military Vicariate of the United States (1979–1983), and Bishop of Scranton in Pennsylvania (1983–1984).

Biography

Early life

O'Connor was born inPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, the fourth of five children of Thomas J. O'Connor, and Dorothy Magdalene (née Gomple) O'Connor (1886–1971), daughter of Gustave Gumpel, a kosher

(also or , ) is a set of dietary laws dealing with the foods that Jewish people are permitted to eat and how those foods must be prepared according to Jewish law. Food that may be consumed is deemed kosher ( in English, yi, כּשר), fro ...

butcher and Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

. In 2014, his sister Mary O'Connor Ward discovered through genealogical research that their mother was born Jewish and was baptized as a Roman Catholic at age 19. John's parents were wed the following year.

O'Connor attended public schools until his

O'Connor attended public schools until his junior year

A junior is person in the third year at an educational institution; usually at a secondary school or at the college and university level, but also in other forms of post-secondary educational institutions. In United States high schools, a junio ...

of high school

A secondary school describes an institution that provides secondary education and also usually includes the building where this takes place. Some secondary schools provide both '' lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper seconda ...

, when he enrolled in West Philadelphia Catholic High School for Boys

West Philadelphia Catholic High School for Boys (West Boys, West Catholic, Burrs) was founded in 1916. A school building was later constructed at 49th Street between Chestnut and Market Streets in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The school closed its d ...

. He then enrolled at St. Charles Borromeo Seminary

Saint Charles Borromeo Seminary is a Roman Catholic seminary in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania that is under the jurisdiction of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. The oldest Catholic institution of higher learning in the Philadelphia region, the school ...

in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania.

Priesthood

Upon graduating from St. Charles, O'Connor was ordained apriest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

for the Archdiocese of Philadelphia

The Roman Catholic Metropolitan Archdiocese of Philadelphia is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in southeastern Pennsylvania, in the United States. It covers the City and County of Philadelphia as well a ...

on December 15, 1945, by Auxiliary Bishop Hugh L. Lamb

Hugh Louis Lamb (October 6, 1890 – December 8, 1959) was an American prelate of the Roman Catholic Church. He served as the first bishop of the Diocese of Greensburg in Pennsylvania from 1951 until his death in 1959. He previously served as ...

. After his ordination, O'Connor was a faculty member at St. James High School in Chester, Pennsylvania

Chester is a city in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, United States. Located within the Philadelphia Metropolitan Area, it is the only city in Delaware County and had a population of 32,605 as of the 2020 census.

Incorporated in 1682, Chester is ...

.

O'Connor joined the United States Navy Chaplain Corps

The United States Navy Chaplain Corps is the body of military chaplains of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services ...

in 1952 during the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

.He was eventually named rear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

and chief of chaplains of the Navy in 1975.He obtained approval for the establishment of the RP eligious Program SpecialistEnlisted Rating, and oversaw the process of standing up this rating, initially accepting transfers from other enlisted rates. The RP rating provided chaplains

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intelligence ...

with a dedicated enlisted community, instead of yeomen transferred to assist a chaplain for a period before returning to their nominal yeoman rate. During this period, he was made an honorary prelate of his holiness

A Prelate of Honour of His Holiness is a Catholic prelate to whom the Pope has granted this title of honour.

They are addressed as Monsignor and have certain privileges as regards clerical clothing.right reverend

The Right Reverend (abbreviated The Rt Revd, The Rt Rev'd, The Rt Rev.) is a style applied to certain religious figures.

Overview

*In the Anglican Communion and the Catholic Church in Great Britain, it applies to bishops, except that ''The M ...

monsignor

Monsignor (; it, monsignore ) is an honorific form of address or title for certain male clergy members, usually members of the Roman Catholic Church. Monsignor is the apocopic form of the Italian ''monsignore'', meaning "my lord". "Monsignor" ca ...

, on October 27, 1966.

O'Connor obtained a master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is an academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice.

in advanced ethics from Villanova University

Villanova University is a Private university, private Catholic church, Roman Catholic research university in Villanova, Pennsylvania. It was founded by the Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinians in 1842 and named after Thomas of Villanova, Sa ...

in Philadelphia. He also received a doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''l ...

in political science from Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private university, private research university in the Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll (archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll in 1789 as Georg ...

, where he studied under the United States' future Ambassador to the United Nations Jeane Kirkpatrick

Jeane Duane Kirkpatrick (née Jordan; November 19, 1926December 7, 2006) was an American diplomat and political scientist who played a major role in the foreign policy of the Ronald Reagan administration. An ardent anticommunist, she was a lo ...

. Kirkpatrick said of O'Connor that he was "... surely one of the two or three smartest graduate students I've ever had."

Auxiliary Bishop of the Military Vicariate US

On April 24, 1979,Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

appointed O'Connor as an auxiliary bishop of the Military Vicariate for the United States and titular bishop

A titular bishop in various churches is a bishop who is not in charge of a diocese.

By definition, a bishop is an "overseer" of a community of the faithful, so when a priest is ordained a bishop, the tradition of the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox an ...

of Cursola. He was consecrated to the episcopate

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

on May 27, 1979, at St. Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal en ...

in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

by John Paul himself, with Cardinals Duraisamy Lourdusamy and Eduardo Somalo as co-consecrators.

Bishop of Scranton

On May 6, 1983, John Paul II named O'Connor as bishop of theDiocese of Scranton

The Diocese of Scranton is a Latin Church ecclesiastical jurisdiction or diocese of the Catholic Church. It is a suffragan see of Archdiocese of Philadelphia, established on March 3, 1868. The seat of the bishop is St. Peter's Cathedral in th ...

, and he was installed in that position on June 29, 1983.

Archbishop of New York

On January 26, 1984, after the death of CardinalTerence Cooke

Terence James Cooke (March 1, 1921 – October 6, 1983) was an American cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. He served as Archbishop of New York from 1968 until his death, quietly battling leukemia throughout his tenure. He was named a cardin ...

, O'Connor was appointed archbishop of the Archdiocese of New York and administrator of the Military Vicariate of the United States; he was installed on March 19.

O'Connor was elevated to cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

in the consistory

Consistory is the anglicized form of the consistorium, a council of the closest advisors of the Roman emperors. It can also refer to:

*A papal consistory, a formal meeting of the Sacred College of Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church

*Consistory ...

of May 25, 1985, with the titular church

In the Catholic Church, a titular church is a church in Rome that is assigned to a member of the clergy who is created a cardinal. These are Catholic churches in the city, within the jurisdiction of the Diocese of Rome, that serve as honorary de ...

of '' Santi Giovanni e Paolo'' in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

(the traditional one for the Archbishop of New York

The Archbishop of New York is the head of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, who is responsible for looking after its spiritual and administrative needs. As the archdiocese is the metropolitan bishop, metropolitan see of the ecclesiastic ...

from 1946 to 2009).

Illness and death

When O'Connor reached the retirement age for bishops of 75 years in January 1995, he submitted his resignation to Pope John Paul II as required bycanon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

, but the Pope did not accept it. He was diagnosed in 1999 as having a brain tumor

A brain tumor occurs when abnormal cells form within the brain. There are two main types of tumors: malignant tumors and benign (non-cancerous) tumors. These can be further classified as primary tumors, which start within the brain, and seconda ...

. He continued to serve as Archbishop of New York until his death.

O'Connor died in the archbishop's residence on May 3, 2000, and was interred in the crypt beneath the main altar of St. Patrick's Cathedral. It was presided over by Cardinal Secretary of State Angelo Sodano

Angelo Raffaele Sodano, GCC (23 November 1927 – 27 May 2022) was an Italian prelate of the Catholic Church and from 1991 on a cardinal. He was the Dean of the College of Cardinals from 2005 to 2019 and Cardinal Secretary of State from 1991 ...

. At O'Connor's request, the homily was delivered by Cardinal Bernard F. Law and the eulogy was delivered by Cardinal William W. Baum.

Attendees include Secretary-General of the United Nations Kofi Annan

Kofi Atta Annan (; 8 April 193818 August 2018) was a Ghanaian diplomat who served as the seventh secretary-general of the United Nations from 1997 to 2006. Annan and the UN were the co-recipients of the 2001 Nobel Peace Prize. He was the founder ...

, US President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

and First Lady Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States sen ...

, Vice President Al Gore

Albert Arnold Gore Jr. (born March 31, 1948) is an American politician, businessman, and environmentalist who served as the 45th vice president of the United States from 1993 to 2001 under President Bill Clinton. Gore was the Democratic Part ...

, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright

Madeleine Jana Korbel Albright (born Marie Jana Korbelová; May 15, 1937 – March 23, 2022) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 64th United States secretary of state from 1997 to 2001. A member of the Democratic ...

, former President George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushSince around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; pr ...

, Texas Governor George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, Bush family, and son of the 41st president George H. W. Bush, he ...

, New York Governor George Pataki

George Elmer Pataki (; born June 24, 1945) is an American lawyer and politician who served as the 53rd governor of New York from 1995 to 2006. An attorney by profession, Pataki was elected mayor of his hometown of Peekskill, New York, and went on ...

, New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani

Rudolph William Louis Giuliani (, ; born May 28, 1944) is an American politician and lawyer who served as the 107th Mayor of New York City from 1994 to 2001. He previously served as the United States Associate Attorney General from 1981 to 198 ...

, former New York City Mayors Ed Koch

Edward Irving Koch ( ; December 12, 1924February 1, 2013) was an American politician, lawyer, political commentator, film critic, and television personality. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1969 to 1977 and was may ...

, and David Dinkins

David Norman Dinkins (July 10, 1927 – November 23, 2020) was an American politician, lawyer, and author who served as the 106th mayor of New York City from 1990 to 1993. He was the first African American to hold the office.

Before enterin ...

.

Legacy

O'Connor was posthumously awarded the

O'Connor was posthumously awarded the Jackie Robinson

Jack Roosevelt Robinson (January 31, 1919 – October 24, 1972) was an American professional baseball player who became the first African American to play in Major League Baseball (MLB) in the modern era. Robinson broke the baseball color line ...

Empire State Medal of Freedom by New York Governor George Pataki

George Elmer Pataki (; born June 24, 1945) is an American lawyer and politician who served as the 53rd governor of New York from 1995 to 2006. An attorney by profession, Pataki was elected mayor of his hometown of Peekskill, New York, and went on ...

on December 21, 2000. On March 7, 2000, O'Connor was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal

The Congressional Gold Medal is an award bestowed by the United States Congress. It is Congress's highest expression of national appreciation for distinguished achievements and contributions by individuals or institutions. The congressional pract ...

by unanimous support in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

and only one vote against - Representative Ron Paul

Ronald Ernest Paul (born August 20, 1935) is an American author, activist, physician and retired politician who served as the U.S. representative for Texas's 22nd congressional district from 1976 to 1977 and again from 1979 to 1985, as well ...

- the resolution in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

.

The John Cardinal O'Connor Pavilion in Riverdale, Bronx

Riverdale is a residential neighborhood in the northwestern portion of the New York City borough of the Bronx. Riverdale, which had a population of 47,850 as of the 2000 United States Census, contains the city's northernmost point, at the College ...

, a residence for retired priests, opened in 2003. The John Cardinal O'Connor School in Irvington, New York

Irvington, sometimes known as Irvington-on-Hudson,Staff (ndg"The Irvington Gazette (Irvington-On-Hudson, N.Y.) 1907-1969"Library of Congress is a suburban village in the town of Greenburgh in Westchester County, New York, United States. It is loca ...

, for students with learning differences

Learning disability, learning disorder, or learning difficulty (British English) is a condition in the brain that causes difficulties comprehending or processing information and can be caused by several different factors. Given the "difficult ...

, opened in 2009. The largest student-run pro-life

Anti-abortion movements, also self-styled as pro-life or abolitionist movements, are involved in the abortion debate advocating against the practice of abortion and its legality. Many anti-abortion movements began as countermovements in respons ...

conference in the United States is also named in his honor. It is held annually at Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private university, private research university in the Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll (archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll in 1789 as Georg ...

.

Upon his death, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' called O'Connor "a familiar and towering presence, a leader whose views and personality were forcefully injected into the great civic debates of his time, a man who considered himself a conciliator, but who never hesitated to be a combatant", and one of the Catholic Church's "most powerful symbols on moral and political issues."

According to New York Mayor Ed Koch

Edward Irving Koch ( ; December 12, 1924February 1, 2013) was an American politician, lawyer, political commentator, film critic, and television personality. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1969 to 1977 and was may ...

: "Cardinal O'Connor was a great man, but he was like the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metony ...

. He was incapable of saving money."

Following his death, SEIU 1199 published a 12-page tribute to O'Connor, calling him "the patron saint of working people". It described his support for low-wage and other workers, his efforts in helping the limousine drivers unionize, his helping end a strike at ''The Daily News'', and his pushing for fringe benefits for minimum-wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation by the end of the 20th century. Bec ...

home health care workers.

Viewpoints

Human life

O'Connor was a forceful opponent of abortion, human cloning,capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

, human trafficking, and unjust war. He assailed what he called the "horror of euthanasia

Euthanasia (from el, εὐθανασία 'good death': εὖ, ''eu'' 'well, good' + θάνατος, ''thanatos'' 'death') is the practice of intentionally ending life to eliminate pain and suffering.

Different countries have different eut ...

", asking rhetorically, "What makes us think that permitted lawful suicide will not become obligated suicide?" In 2000, O'Connor called for a "major overhaul" of the punitive Rockefeller drug laws

The Rockefeller Drug Laws are the statutes dealing with the sale and possession of "narcotic" drugs in the New York State Penal Law. The laws are named after Nelson Rockefeller, who was the state's governor at the time the laws were adopted. Rock ...

in New York State, which he believed produced "grave injustices".

US foreign policy

O'Connor offered severe critiques of some United States military policies. In the 1980s, he condemned US support for counterrevolutionary guerrilla forces inCentral America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

, opposed the U.S. mining of the waters off Nicaragua, questioned spending on new weapons systems, and preached caution in regard to American military actions abroad.

In 1998, O'Connor questioned whether the United States' cruise missile strikes on Afghanistan and Sudan were morally justifiable. In 1999, during the Kosovo War

The Kosovo War was an armed conflict in Kosovo that started 28 February 1998 and lasted until 11 June 1999. It was fought by the forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (i.e. Serbia and Montenegro), which controlled Kosovo before the war ...

, he used his weekly column in the archdiocesan newspaper, ''Catholic New York'', to challenge repeatedly the morality of NATO's bombing campaign of Yugoslavia, suggesting that it did not meet the Catholic Church's criteria for a Just War

The just war theory ( la, bellum iustum) is a doctrine, also referred to as a tradition, of military ethics which is studied by military leaders, theologians, ethicists and policy makers. The purpose of the doctrine is to ensure that a war is m ...

, and going so far as to ask, "Does the relentless bombing of Yugoslavia prove the power of the Western world or its weakness?" Three years before the 9/11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated Suicide attack, suicide List of terrorist incidents, terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, ...

on New York City, which occurred after his death, O'Connor insisted that the traditional Just War

The just war theory ( la, bellum iustum) is a doctrine, also referred to as a tradition, of military ethics which is studied by military leaders, theologians, ethicists and policy makers. The purpose of the doctrine is to ensure that a war is m ...

principles must be applied to evaluate the morality of military responses to unconventional warfare

Unconventional warfare (UW) is broadly defined as "military and quasi-military operations other than conventional warfare" and may use covert forces, subversion, or guerrilla warfare. This is typically done to avoid escalation into conventional ...

and terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

.

Organized labor

O'Connor's father had been a lifelongunion

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

member and O'Connor was a passionate defender of organized labor

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and Employee ben ...

, as well as an advocate for the poor and the homeless.

During a strike

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

*Airstrike, military strike by air forces on either a suspected ...

in 1984 by SEIU 1199, the largest health care workers union in New York City, O'Connor strongly criticized the League of Voluntary Hospitals, of which the archdiocese was a member, for threatening to fire striking union members who refused to return to work, calling it "strikebreaking

A strikebreaker (sometimes called a scab, blackleg, or knobstick) is a person who works despite a strike. Strikebreakers are usually individuals who were not employed by the company before the trade union dispute but hired after or during the str ...

" and vowing that no Catholic hospital would do so. The following year, when a contract with SEIU 1199 still had not been reached, he threatened to break with the League and settle with the union unilaterally to reach an agreement "that gives justice to the workers".

In his homily

A homily (from Greek ὁμιλία, ''homilía'') is a commentary that follows a reading of scripture, giving the "public explanation of a sacred doctrine" or text. The works of Origen and John Chrysostom (known as Paschal Homily) are considered ex ...

during a Labor Day

Labor Day is a federal holiday in the United States celebrated on the first Monday in September to honor and recognize the American labor movement and the works and contributions of laborers to the development and achievements of the United St ...

mass at St. Patrick's in 1986, O'Connor expressed his strong commitment to organized labor: " many of our freedoms in this country, so much of the building up of society, is precisely attributable to the union movement, a movement that I personally will defend despite the weakness of some of its members, despite the corruption with which we are all familiar that pervades all society, a movement that I personally will defend with my life."In 1987, when the television broadcast employees' union was on strike against the National Broadcasting Corporation (

NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an Television in the United States, American English-language Commercial broadcasting, commercial television network, broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Enterta ...

), a non-union crew from NBC appeared at the cardinal's residence to cover one of O'Connor's press conferences

A press conference or news conference is a media event in which notable individuals or organizations invite journalists to hear them speak and ask questions. Press conferences are often held by politicians, corporations, non-governmental organ ...

. O'Connor declined to admit them, directing his secretary to "tell them they're not invited."

Relations with Jewish community

O'Connor played an active role in Catholic–Jewish relations. He strongly denouncedanti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, declaring that one "cannot be a faithful Christian and an anti-Semite. They are incompatible, because anti-Semitism is a sin." He wrote an apology to Jewish leaders in New York City for past harm done to the Jewish community.

O'Connor criticized the failure of Swiss banks

Banking in Switzerland dates to the early eighteenth century through Switzerland's merchant trade and has, over the centuries, grown into a complex, regulated, and international industry. Banking is seen as emblematic of Switzerland, along with ...

' to compensate Jewish Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

victims whose assets were deposited in Switzerland by German Nazi leaders. He called it "a human rights issue, an issue of the human race." Even when disagreeing with him over political questions, Jewish leaders acknowledged that O'Connor was "a friend, a powerful voice against anti-Semitism".

The Jewish Council for Public Affairs

The Jewish Council for Public Affairs (JCPA) is an American Jewish 501(c)(3) tax exempt organization that deals with community relations. It is a coordinating round table organization of 15 other national Jewish organizations, including the Re ...

called O'Connor , "a true friend and champion of Catholic–Jewish relations, nda humanitarian

Humanitarianism is an active belief in the value of human life, whereby humans practice benevolent treatment and provide assistance to other humans to reduce suffering and improve the conditions of humanity for moral, altruistic, and emotional ...

who used the power of his pulpit to advocate for disadvantaged people throughout the world and in his own community." Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel

Elie Wiesel (, born Eliezer Wiesel ''Eliezer Vizel''; September 30, 1928 – July 2, 2016) was a Romanian-born American writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Peace Prize, Nobel laureate, and Holocaust survivor. He authored Elie Wiesel b ...

called O'Connor, "a good Christian" and a man "who understands our pain."

Relations with the LGBT community

St. Patrick's protest and work with HIV/AIDS patients

On December 10, 1989, 4,500 members of ACT UP andWomen's Health Action and Mobilization

Women's Health Action and Mobilization (WHAM!) was an American activist organization based in New York City, established in 1989 in response to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in ''Webster v. Reproductive Health Services'' that states may bar the use ...

(WHAM) held a demonstration at St. Patrick's Cathedral to voice their opposition to O'Connor's positions on HIV/AIDS education, the distribution of condoms in public schools, and abortion rights

Abortion-rights movements, also referred to as pro-choice movements, advocate for the right to have legal access to induced abortion services including elective abortion. They seek to represent and support women who wish to terminate their pre ...

for women. The protest resulted in 43 arrests inside the cathedral. O'Connor believed that Catholic teaching taught that homosexual acts

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peo ...

are never permissible, while homosexual desires are disordered but not in themselves sinful.

O'Connor made an effort to minister to 1,000 people dying of HIV/AIDS

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual ...

and their families, following up on other HIV/AIDS patients. He visited Saint Vincent's Catholic Medical Center

Saint Vincent Catholic Medical Centers of New York d/b/a as Saint Vincent's Catholic Medical Centers (Saint Vincent's, or SVCMC) was a healthcare system, anchored by its flagship hospital, St. Vincent's Hospital Manhattan, locally referred to a ...

, where he cleaned the sores and emptied the bedpans of more than 1,100 patients. According to reports, O'Connor was popular with the Saint Vincent's patients, many of whom did not know he was the archbishop, and was supportive of other priests who ministered to gay men and others with HIV/AIDS. O'Connor personally led the 1990 funeral mass for James Zappalorti

James Patrick Zappalorti (September 29, 1945 – January 22, 1990), a disabled veteran of the Vietnam War, was the victim of a highly publicized, fatal gay-bashing attack on Staten Island, New York. The murder led to increased efforts to pass a st ...

, a gay man who was murdered on Staten Island, New York

Staten Island ( ) is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey b ...

. O'Connor endorsed a statewide hate crime law

A hate crime (also known as a bias-motivated crime or bias crime) is a prejudice-motivated crime which occurs when a perpetrator targets a victim because of their membership (or perceived membership) of a certain social group or racial demograph ...

that included crimes motivated by sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is an enduring pattern of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. These attractions are generall ...

, which passed shortly after his own death in 2000.

Executive Order 50

O'Connor actively opposed Executive Order 50, a mayoral order issued in 1980 by New York MayorEd Koch

Edward Irving Koch ( ; December 12, 1924February 1, 2013) was an American politician, lawyer, political commentator, film critic, and television personality. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1969 to 1977 and was may ...

. Order 50 required all city contractors, including religious entities, to provide services on a non-discriminatory basis with respect to race, creed, age, sex, handicap, as well as "sexual orientation or preference". After the Salvation Army

The Salvation Army (TSA) is a Protestant church and an international charitable organisation headquartered in London, England. The organisation reports a worldwide membership of over 1.7million, comprising soldiers, officers and adherents col ...

received a warning from the city that its contracts for child care services would be canceled for refusing to comply with the executive order's provisions regarding sexual orientation, the Archdiocese of New York and Agudath Israel, an Orthodox Jewish

Orthodox Judaism is the collective term for the traditionalist and theologically conservative branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Written and Oral, as revealed by God to Moses on M ...

organization, threatened to cancel their contracts with the city if forced to comply. O'Connor maintained that the executive order would cause the Catholic Church to appear to condone homosexual activity. Writing in ''Catholic New York'' in January 1985, O'Connor characterized the order as "an exceedingly dangerous precedent hat would

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

invite unacceptable governmental intrusion into and excessive entanglement with the Church's conducting of its own internal affairs." Drawing the traditional Catholic distinction between homosexual "inclinations" and "behavior", he stated that "we do not believe that homosexual behavior ... should be elevated to a protected category."

We do not believe that religious agencies should be required to employ those engaging in or advocating homosexual behavior. We are willing to consider on a case-by-case basis the employment of individuals who have engaged in or may at some future time engage in homosexual behavior. We approach those who have engaged in or may engage in what the Church considers illicit heterosexual behavior the same way. ...We believe, however, that only a religious agency itself can properly determine the requirements of any particular job within that agency, and whether or not a particular individual meets or is reasonably likely to meet such requirements.Subsequently, the Salvation Army, the archdiocese, and Agudath Israel, together with the

Chamber of Commerce and Industry

A chamber of commerce, or board of trade, is a form of business network. For example, a local organization of businesses whose goal is to further the interests of businesses. Business owners in towns and cities form these local societies to ad ...

, sued the City of New York to overturn Executive Order 50 on the grounds that the mayor had exceeded his executive authority in issuing it. In September 1984, the New York Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the State of New York is the trial-level court of general jurisdiction in the New York State Unified Court System. (Its Appellate Division is also the highest intermediate appellate court.) It is vested with unlimited civ ...

agreed with the plaintiffs. It struck down that part of the order that prohibited discrimination based upon "sexual orientation or affectational preference" on the grounds that the mayor had exceeded his authority. In June 1985, New York's highest court upheld the lower court's decision striking down Executive Order 50.

O'Connor vigorously and actively opposed city

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

and state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

legislation guaranteeing LGBT civil rights, including legislation (supported by then-mayors Ed Koch

Edward Irving Koch ( ; December 12, 1924February 1, 2013) was an American politician, lawyer, political commentator, film critic, and television personality. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1969 to 1977 and was may ...

, David Dinkins, and Rudy Giuliani

Rudolph William Louis Giuliani (, ; born May 28, 1944) is an American politician and lawyer who served as the 107th Mayor of New York City from 1994 to 2001. He previously served as the United States Associate Attorney General from 1981 to 198 ...

) prohibiting discrimination based upon sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is an enduring pattern of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. These attractions are generall ...

in housing, public accommodations and employment.

St. Patrick's Day parade

O'Connor also supported the decision by theAncient Order of Hibernians

The Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH; ) is an Irish Catholic fraternal organization. Members must be male, Catholic, and either born in Ireland or of Irish descent. Its largest membership is now in the United States, where it was founded in New ...

to exclude the Irish Lesbian and Gay Organization from marching under its own banner in New York City's St. Patrick's Day

Saint Patrick's Day, or the Feast of Saint Patrick ( ga, Lá Fhéile Pádraig, lit=the Day of the Festival of Patrick), is a cultural and religious celebration held on 17 March, the traditional death date of Saint Patrick (), the foremost patr ...

parade. The Hibernians argued that their decision as to which organizations may march in the parade, which honors Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick ( la, Patricius; ga, Pádraig ; cy, Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, the other patron saints be ...

, a Catholic saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern Ortho ...

, was protected by the First Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

and that they could not be compelled to admit a group whose beliefs conflicted with theirs. In 1992, in a decision criticized by the New York Civil Liberties Union

The New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) is a civil rights organization in the United States. Founded in November 1951 as the New York affiliate of the American Civil Liberties Union, it is a not-for-profit, nonpartisan organization with nearl ...

, the City of New York ordered the Hibernians to admit the Irish Lesbian and Gay Organization to march in the parade. The city subsequently denied the Hibernians a permit for the parade until, in 1993, a federal judge Federal judges are judges appointed by a federal level of government as opposed to the state/provincial/local level.

United States

A US federal judge is appointed by the US President and confirmed by the US Senate in accordance with Article 3 of ...

in New York held that the city's permit denial was "patently unconstitutional

Constitutionality is said to be the condition of acting in accordance with an applicable constitution; "Webster On Line" the status of a law, a procedure, or an act's accordance with the laws or set forth in the applicable constitution. When l ...

" because the parade was private, not public, and constituted "a pristine form of speech

Speech is a human vocal communication using language. Each language uses Phonetics, phonetic combinations of vowel and consonant sounds that form the sound of its words (that is, all English words sound different from all French words, even if ...

" as to which the parade sponsor had a right to control the content and tone.

In 1987, O'Connor prohibited DignityUSA

DignityUSA is an organization with headquarters in Boston, Massachusetts, that focuses on LGBT rights and the Homosexuality and Catholicism, Catholic Church. Dignity Canada exists as the Canadian sister organization. The organization is made up of ...

, an organization of LGBT Catholics, from holding masses in parishes in the archdiocese. After eight years of protests by the group, O'Connor started meeting with the DignityUSA twice a year.

HIV and condom controversy

Contraception and condom distribution

O'Connor opposed condom distribution as an AIDS-prevention measure, viewing it as being contrary to the Catholic Church's teaching thatcontraception

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

is immoral and its use a sin. O'Connor rejected the argument that condom

A condom is a sheath-shaped barrier device used during sexual intercourse to reduce the probability of pregnancy or a sexually transmitted infection (STI). There are both male and female condoms. With proper use—and use at every act of in ...

s distributed to gay men are not contraceptives. O'Connor's response was that using an "evil act" was not justified by good intentions, and that the church should not be seen as encouraging sinful acts among others (other fertile heterosexual couples who might wrongly interpret his narrow support as license for their own contraception). He also claimed that sexual abstinence

Sexual abstinence or sexual restraint is the practice of refraining from some or all aspects of Human sexual activity, sexual activity for medical, psychological, legal, social, financial, philosophical, moral, or religious reasons. Sexual abstin ...

is a sure way to prevent infection, claiming condoms were only 50% effective against HIV transmission

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual m ...

. HIV activist group ACT UP

AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) is an international, grassroots political group working to end the AIDS pandemic. The group works to improve the lives of people with AIDS through direct action, medical research, treatment and advocacy, ...

(AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) criticized the cardinal's opinion, leading to confrontations between the group and O'Connor.

Early on in the AIDS epidemic, O'Connor approved the opening of a specialized AIDS unit to provide medical care for the sick and dying in the former St. Clare's Hospital in Manhattan, the first of its kind in the state. He often nurtured and ministered to dying AIDS patients, many of whom were homosexual. Some members of ACT UP protested in front of St. Patrick's Cathedral, holding placards such as "Cardinal O'Connor Loves Gay People ... If They Are Dying of AIDS."

Watkins Commission

In 1987, US PresidentRonald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

appointed O'Connor to the President's Commission on the HIV Epidemic The President's Commission on the HIV Epidemic was a commission formed by President Ronald Reagan in 1987 to investigate the AIDS pandemic. It is also known as the Watkins Commission for James D. Watkins, its chairman when the commission issued it ...

, also known as the Watkins Commission. O'Connor served with 12 other members, few of whom were AIDS experts, including James D. Watkins

James David Watkins (March 7, 1927 – July 26, 2012) was a United States Navy Admiral (United States), admiral and former Chief of Naval Operations who served as the United States Secretary of Energy during the George H. W. Bush administration, ...

, Richard DeVos

Richard Marvin DeVos Sr. (March 4, 1926 – September 6, 2018) was an American billionaire businessman, co-founder of Amway with Jay Van Andel (company restructured as Alticor in 2000), and owner of the Orlando Magic basketball team. In 2012 ...

, and Penny Pullen

Penny Pullen (born March 2, 1947) is an American politician and conservative activist. Pullen spent eight terms in the Illinois General Assembly representing a district in the northwest suburbs of Chicago. Pullen also served on various presiden ...

. The commission was initially controversial among HIV researchers and activists as lacking expertise on the disease and as being in disarray. The Watkins Commission surprised many of its critics, however, by issuing a final report in 1988 that lent conservative support for antibias laws to protect HIV-positive

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of ''Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the ...

people, on-demand treatment for drug addicts, and the speeding of AIDS-related research. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' praised the commission's "remarkable strides" and its proposed $2 billion campaign against AIDS among drug addicts. The Watkins Commission's recommendations were similar to the recommendations subsequently made by a committee of HIV experts appointed by the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

.

Theodore McCarrick

O'Connor was involved with the career ofTheodore McCarrick

Theodore Edgar McCarrick (born July 7, 1930) is a laicized American bishop and former cardinal of the Catholic Church. Ordained a priest in 1958, he became an auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of New York in 1977, then became Bishop of Metuch ...

, a prominent figure in the American hierarchy. McCarrick was the subject of rumors for many years that he had sexually abused seminarians; McCarrick resigned from the College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals, or more formally the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. its current membership is , of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Cardinals are appoi ...

in 2018 and was laicized in 2019. O'Connor grew more skeptical of McCarrick over the years.

In April 1986, O'Connor strongly endorsed making McCarrick Archbishop of Newark. In 1992 and 1993 he received several anonymous letters accusing McCarrick of sexually abusing seminarians, and he shared them with McCarrick. In 1994, on behalf of the Apostolic Nuncio to the U.S., who was concerned about a potential scandal, he arranged for an investigation into rumors McCarrick, then Archbishop of Newark, had engaged in inappropriate sexual behavior with seminarians and he concluded that there were "no impediments" to including Newark on a planned papal visit to the U.S.

In October 1996, though two psychiatrists found a priest's charge of sexual abuse by McCarrick credible, O'Connor remained skeptical.That same month, however, he intervened to prevent a priest "too closely identified" with McCarrick from becoming an auxiliary bishop citing "a rather unsettled climate of opinion about certain issues" in Newark.

In October 1999, when McCarrick was under consideration for transfer to a more important see than Newark, O'Connor wrote a letter to the Apostolic Nuncio to the U.S. and the Congregation for Bishops

The Dicastery for Bishops, formerly named Congregation for Bishops (), is the department of the Roman Curia that oversees the selection of most new bishops. Its proposals require papal approval to take effect, but are usually followed. The Dic ...

—a letter that Pope John Paul II read—that summarized the charges against McCarrick, especially his repeatedly arranging for seminarians and other men to share his bed. O'Connor concluded: "I regret that I would have to recommend very strongly against such promotion." McCarrick learned about this letter from contacts in the Curia and in August 2000, several months after O'Connor's death, wrote a rebuttal that convinced John Paul II to appoint him archbishop of Washington.

References

Cited works

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Oconnor, John Joseph 1920 births 2000 deaths Clergy from Philadelphia American Roman Catholic clergy of Irish descent Villanova University alumni St. Charles Borromeo Seminary alumni Korean War chaplains United States Navy chaplains Walsh School of Foreign Service alumni United States Navy rear admirals (upper half) Chiefs of Chaplains of the United States Navy People from Scranton, Pennsylvania Roman Catholic archbishops of New York 20th-century American cardinals American people of Jewish descent American anti-abortion activists Congressional Gold Medal recipients Founders of Catholic religious communities Knights of Malta Cardinals created by Pope John Paul II Deaths from cancer in New York (state) Deaths from brain cancer in the United States Burials at St. Patrick's Cathedral (Manhattan) Catholics from Pennsylvania