John Howard Moore on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

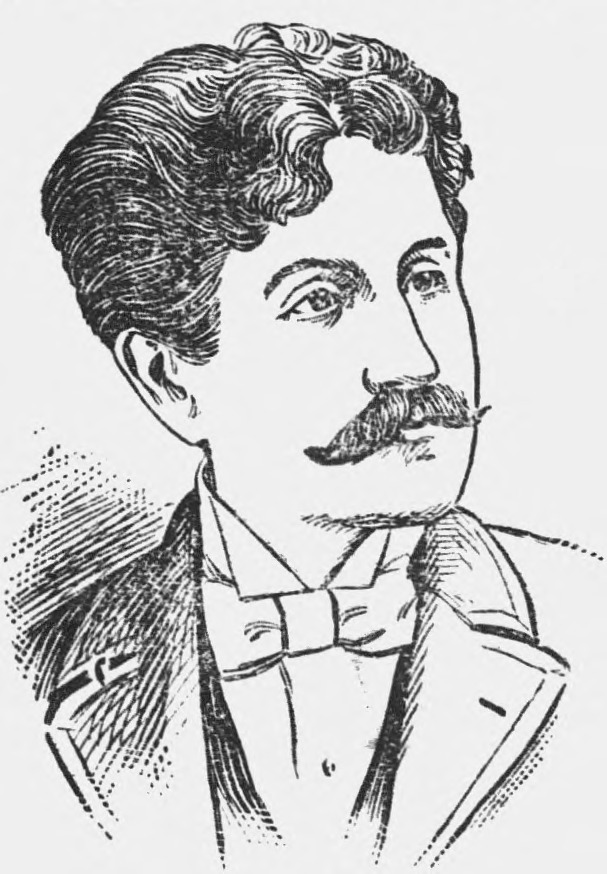

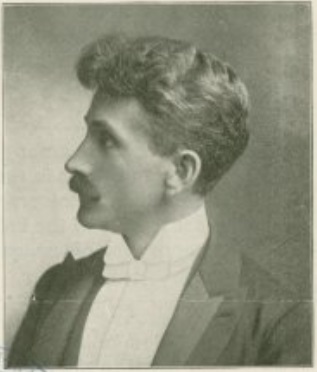

John Howard Moore (December 4, 1862 – June 17, 1916) was an American zoologist, philosopher, educator, humanitarian and socialist. He is considered to be an early, yet neglected, proponent of

From 1890 to 1893, Moore continued to work as a lecturer. He also gave lectures on behalf of the

From 1890 to 1893, Moore continued to work as a lecturer. He also gave lectures on behalf of the

In 1899, Moore published his first book, ''Better-World Philosophy'', to mixed reviews. In the book, he expressed a longing to change how humans perceive the world and his view that all beings are interconnected. Moore argued that

In 1899, Moore published his first book, ''Better-World Philosophy'', to mixed reviews. In the book, he expressed a longing to change how humans perceive the world and his view that all beings are interconnected. Moore argued that  In 1909, a law was passed in Illinois prescribing teaching of morals in public schools for 30 minutes each week. Contrary to his fellow teachers, Moore was pleased by the law and began preparing supporting educational materials. He published ''Ethics and Education'', in 1912, as an aid for teachers who were having trouble implementing the new educational requirements. Before the book's publication, Moore sparked controversy when he made available extracts of the book which were critical of the courts and marriage. In an interview, Moore defended the content of the book, inviting the board of education to investigate him if necessary. In the same year, he published ''High-School Ethics: Book One'', which was intended to form the first part of a four-year high school course covering theoretical and practical ethics and covered a variety of topics including the ethics of school life; properly caring for pets; women's rights; birds; where sealskin, ivory and other animal products are sourced from; and good habits. Moore also published a pamphlet titled ''The Ethics of School Life'', which was based on a lesson that Moore gave to high-school students.

Moore wrote to Salt on 25 March 1911 about his experience of depression and a breakdown from overwork. He told Salt that the books he had written might not result in much, but that he felt he put a lot of effort into producing them.

In February 1912, a meeting of the Schoolmasters' Club of Chicago, of which Moore was a member, was disrupted because they did not agree with his views; Moore responded: "I am a radical and a socialist, but I do not allow my radicalism nor my socialism to enter into my teachings."

Moore delivered a speech at the International Anti-vivisection and Animal protection Congress, held in Washington D.C, in 1913; in the speech, he claimed that vivisection and the consumption of meat are both a product of anthropocentrism and that Darwin's ''

In 1909, a law was passed in Illinois prescribing teaching of morals in public schools for 30 minutes each week. Contrary to his fellow teachers, Moore was pleased by the law and began preparing supporting educational materials. He published ''Ethics and Education'', in 1912, as an aid for teachers who were having trouble implementing the new educational requirements. Before the book's publication, Moore sparked controversy when he made available extracts of the book which were critical of the courts and marriage. In an interview, Moore defended the content of the book, inviting the board of education to investigate him if necessary. In the same year, he published ''High-School Ethics: Book One'', which was intended to form the first part of a four-year high school course covering theoretical and practical ethics and covered a variety of topics including the ethics of school life; properly caring for pets; women's rights; birds; where sealskin, ivory and other animal products are sourced from; and good habits. Moore also published a pamphlet titled ''The Ethics of School Life'', which was based on a lesson that Moore gave to high-school students.

Moore wrote to Salt on 25 March 1911 about his experience of depression and a breakdown from overwork. He told Salt that the books he had written might not result in much, but that he felt he put a lot of effort into producing them.

In February 1912, a meeting of the Schoolmasters' Club of Chicago, of which Moore was a member, was disrupted because they did not agree with his views; Moore responded: "I am a radical and a socialist, but I do not allow my radicalism nor my socialism to enter into my teachings."

Moore delivered a speech at the International Anti-vivisection and Animal protection Congress, held in Washington D.C, in 1913; in the speech, he claimed that vivisection and the consumption of meat are both a product of anthropocentrism and that Darwin's ''

On June 17, 1916, at the age of 53, Moore died after shooting himself in the head with a revolver on Wooded Island in Jackson Park, Chicago. He had visited the island regularly to observe and study birds. Moore had struggled for many years with a long illness and

On June 17, 1916, at the age of 53, Moore died after shooting himself in the head with a revolver on Wooded Island in Jackson Park, Chicago. He had visited the island regularly to observe and study birds. Moore had struggled for many years with a long illness and

The Cost of a Skin

' (London:

The Care of Illegitimate Children in Chicago

' (Chicago: Juvenile Protective Association of Chicago, 1912) * ''The Ethics of School Life: A Lesson Given at the Crane Technical High School, Chicago, in Accordance with the Law Requiring the Teaching of Morals in the Public Schools of Illinois'' (London: G. Bell & Sons, 1912)

J. Howard Moore

at Animal Rights Library

at The Clarence Darrow Digital Collection

Photograph of J. Howard Moore and his wife Jennie

{{DEFAULTSORT:Moore, J. Howard 1862 births 1916 suicides 19th-century American biographers 19th-century American educators 19th-century American essayists 19th-century American journalists 19th-century American male singers 19th-century American singers 19th-century American male writers 19th-century American non-fiction writers 19th-century American philosophers 19th-century American zoologists 19th-century social scientists 20th-century American biographers 20th-century American educators 20th-century American essayists 20th-century American journalists 20th-century American male singers 20th-century American singers 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American philosophers 20th-century American zoologists 20th-century social scientists American animal rights activists American animal rights scholars American atheist writers American atheists American columnists American education writers American ethicists American eugenicists American former Christians American humanitarians American male non-fiction writers American newspaper reporters and correspondents American pamphleteers American public speakers American science writers American socialists American suffragists American temperance activists American vegetarianism activists Animal ethicists Anti-imperialism Anti-vivisectionists Birdwatchers Burials in Kansas Drake University alumni Educational reformers Education writers Injuries from lightning strikes Oskaloosa College alumni People from Rockville, Indiana Public orators Sentientists Schoolteachers from Indiana Sex education advocates Suicides by firearm in Illinois University of Chicago alumni University of Chicago faculty University of Wisconsin people Utilitarians

animal rights

Animal rights is the philosophy according to which many or all sentient animals have moral worth that is independent of their utility for humans, and that their most basic interests—such as avoiding suffering—should be afforded the sa ...

and ethical vegetarianism

Conversations regarding the ethics of eating meat are focused on whether or not it is moral to eat non-human animals. Ultimately, this is a debate that has been ongoing for millennia, and it remains one of the most prominent topics in food ethics ...

, and was a leading figure in the American humanitarian movement. Moore was a prolific writer, authoring numerous articles, books, essays, pamphlets on topics including animal rights, education, ethics, evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes (natural selection, common descent, speciation) that produced the diversity of life on Earth. It is also defined as the study of the history of life fo ...

, humanitarianism

Humanitarianism is an active belief in the value of human life, whereby humans practice benevolent treatment and provide assistance to other humans to reduce suffering and improve the conditions of humanity for moral, altruistic, and emotional ...

, socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

, temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

, utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charact ...

and vegetarianism. He also lectured on many of these subjects and was widely regarded as a talented orator, earning the name the "silver tongue of Kansas" for his lectures on prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

.

Moore was born near Rockville, Indiana

Rockville is a town in Adams Township, Parke County, in the U.S. state of Indiana. The population was 2,607 at the 2010 census. The town is the county seat of Parke County. It is known as "The Covered Bridge Capital of the World".

History

Rockv ...

, in 1862 and spent his formative years in Linden, Missouri. Raised as a Christian, this instilled in him the anthropocentric

Anthropocentrism (; ) is the belief that human beings are the central or most important entity in the universe. The term can be used interchangeably with humanocentrism, and some refer to the concept as human supremacy or human exceptionalism. ...

belief that non-human animals existed for the benefit of humans. At college, Moore was introduced to Darwin's theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation t ...

, which led him to develop an ethic that rejected both Christianity and anthropocentrism, and recognized the intrinsic value of animals; he adopted vegetarianism as an extension of this belief. While studying zoology at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

, he became a socialist, helped form the university's Vegetarian Eating Club and won a national oratorical contest on prohibition. Moore was an influential member of the Chicago Vegetarian Society

Carrica Le Favre (born June, 1850) was an American physical culturist, dress reform advocate and vegetarianism activist. She founded the Chicago Vegetarian Society and the New York Vegetarian Society.

Biography

Le Favre was well known as a ch ...

and attempted to model the organization as an American version of the Humanitarian League

The Humanitarian League was a British radical advocacy group formed by Henry S. Salt and others to promote the principle that it is wrong to inflict avoidable suffering on any sentient being. It was based in London and operated between 189 ...

, a British organization that Moore was also a member of. In 1895, Moore delivered a speech that was published by the Chicago Vegetarian Society as '' Why I Am a Vegetarian''. For the rest of his life, Moore worked as a teacher in Chicago, while continuing to lecture and write.

In 1899, Moore published his first book ''Better-World Philosophy'', in which he described what he saw as fundamental problems in the world and his ideal arrangement of the universe''.'' In 1906, his best-known work ''The Universal Kinship

''The Universal Kinship'' is a 1906 book by American zoologist, philosopher, educator and socialist J. Howard Moore. In the book, Moore advocated for a secular Sentiocentrism, sentiocentric philosophy, called the Universal Kinship, which mandated ...

'' was published, in which he advocated for a sentiocentric philosophy he called the doctrine of Universal Kinship, based on the shared evolutionary

Evolution is change in the heredity, heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the Gene expression, expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to ...

kinship between all sentient beings

Sentience is the capacity to experience feelings and sensations. The word was first coined by philosophers in the 1630s for the concept of an ability to feel, derived from Latin '' sentientem'' (a feeling), to distinguish it from the ability to ...

. Moore expanded on his ideas in ''The New Ethics

''The New Ethics'' is a 1907 book by the American zoologist and philosopher J. Howard Moore, in which he advocates for a form of ethics, that he calls the New Ethics, which applies the principle of the Golden Rule—treat others as you would wan ...

'' the following year. In response to the passing of a law in Illinois prescribing the teaching of morals in public schools, Moore published supporting education material, in the form of two books and a pamphlet. This was followed by two books on evolution: ''The Law of Biogenesis'' (1914) and ''Savage Survivals'' (1916). After having suffered from chronic illness and depression for several years, Moore killed himself at the age of 53 in Jackson Park, Chicago

Jackson Park is a park located on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois. It was originally designed in 1871 by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, then greatly remodeled in 1893 to serve as the site of the World's Columbian Exposition, leaving ...

.

Biography

Early life and education

John Howard Moore was born on December 4, 1862, nearRockville, Indiana

Rockville is a town in Adams Township, Parke County, in the U.S. state of Indiana. The population was 2,607 at the 2010 census. The town is the county seat of Parke County. It is known as "The Covered Bridge Capital of the World".

History

Rockv ...

. Moore was the eldest of the six children of William A. Moore and Mary Moore (née Barger). At the age of six months, the Moore family moved to Linden, Missouri. During the first 30 years of his life, Moore and his family moved between Kansas, Missouri and Iowa.

Moore had a Christian upbringing, which instilled in him the anthropocentric

Anthropocentrism (; ) is the belief that human beings are the central or most important entity in the universe. The term can be used interchangeably with humanocentrism, and some refer to the concept as human supremacy or human exceptionalism. ...

belief that humans were created by God to have dominion over the Earth and its inhabitants. Growing up on a farm, Moore was fond of hunting and this fondness was shared by the people around him; he later reflected that he and his community saw animals as existing to be used for whatever purpose was seen fit.

Moore studied at High Bank school till the age of 17, before studying for one year at a college in Rock Port, Missouri

Rock Port is a city in, and the county seat of, Atchison County, Missouri, Atchison County, Missouri, United States. The population was 1,278 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census.

History

Rock Port was laid out in 1851. The city, whic ...

. He then studied at Oskaloosa College

Oskaloosa College was a liberal arts college based out of Oskaloosa, Iowa. Work was begun on establishing the college in 1855, under the influence of Aaron Chatterson and was affiliated with the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). The college ...

(now defunct), in Iowa, from 1880 to 1884, but did not graduate. Moore went on to study at Drake University

Drake University is a private university in Des Moines, Iowa. It offers undergraduate and graduate programs, including professional programs in business, law, and pharmacy. Drake's law school is among the 25 oldest in the United States.

Hi ...

. Studying science introduced Moore to Darwin's theory of evolution, which led to him to reject Christianity, in favour of an ethic based on Darwin's theory which recognized the intrinsic value of animals as independent of their value to humans.

In 1884, he became an examiner for the Board of Teachers for Mitchell County, Kansas

Mitchell County (standard abbreviation: MC) is a county located in the U.S. state of Kansas. As of the 2020 census, the county population was 5,796. The largest city and county seat is Beloit.

History

Early history

For many millennia, the G ...

. The following year, Moore was struck by lightning, receiving burns to his arm and chest and temporarily losing his sight and capacity for speech; he recovered after six days of bed rest. For the rest of his life, Moore suffered from severe headaches as a result of the injury. In 1886, he unsuccessfully ran for a seat in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

, coming last out of five. Around this time, he became a vegetarian for ethical reasons.

In Cawker City, Kansas

Cawker City is a city in Mitchell County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 457. The city is located along the north shore of Waconda Lake and Glen Elder State Park. It is one of several places cl ...

, Moore studied law under C. H. Hawkins. In 1889, he was employed by the National Lecture Bureau, delivering lectures in a manner which led him to be known as the "silver tongue of Kansas"; he was also described as a "youthful Luther" and was celebrated for both his oratory and singing voice. Moore delivered lectures in Kansas, Missouri and Iowa.

In 1890, Moore published his first pamphlet ''A Race of Somnambulists'', in which he criticized the cruelty of humans towards the animal world. He spent the summer of the same year in Chautauqua, New York

Chautauqua ( ) is a town and lake resort community in Chautauqua County, New York, United States. The population was 4,017 at the 2020 census. The town is named after Chautauqua Lake. It is the home of the Chautauqua Institution and the birthplac ...

, studying voice culture in singing and speaking at the Chautauqua Institution

The Chautauqua Institution ( ) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit education center and summer resort for adults and youth located on in Chautauqua, New York, northwest of Jamestown in the Western Southern Tier of New York State. Established in 1874, the ...

.

From 1890 to 1893, Moore continued to work as a lecturer. He also gave lectures on behalf of the

From 1890 to 1893, Moore continued to work as a lecturer. He also gave lectures on behalf of the Women's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

. Around this time, Moore, who was living on a farm to the south of Cawker City, worked as a reporter for ''The Beloit Daily Call'', sending in rural correspondence about happenings in his local area.

In 1894, Moore started at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

with advanced academic standing. While studying there, he became a socialist, and helped form the Vegetarian Eating Club at the university, serving as president in 1895 and the following year as purveyor; he was also vice president of the university's prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

club.

Moore was an influential member of the Chicago Vegetarian Society

Carrica Le Favre (born June, 1850) was an American physical culturist, dress reform advocate and vegetarianism activist. She founded the Chicago Vegetarian Society and the New York Vegetarian Society.

Biography

Le Favre was well known as a ch ...

and the Humanitarian League

The Humanitarian League was a British radical advocacy group formed by Henry S. Salt and others to promote the principle that it is wrong to inflict avoidable suffering on any sentient being. It was based in London and operated between 189 ...

, a British radical advocacy group; under his direction, he modelled the Society as an American version of the League. In 1895, Moore delivered a speech in front of the society, published in the same year as '' Why I Am a Vegetarian'', in which he explained his reasoning for not eating meat. A month after the speech, Moore took first honors in the University of Chicago Prohibition Club's annual oratory contest for his oration "The Scourge of the Republic". That April, he represented the university at the state prohibition contest in Wheaton, Illinois

Wheaton is a suburban city in Milton and Winfield Townships and is the county seat of DuPage County, Illinois. It is located approximately west of Chicago. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 52,894, which was estimated ...

, again winning first honors. He went on to win first honors at the national contest in Cleveland. In a newspaper profile, Moore was described as a passionate supporter of women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

, with curly hair and soulful eyes.

Moore graduated in April 1896, earning an A.B. degree in zoology. That summer, he accepted the chair of sociology at Wisconsin State University, lecturing on the topic of social progress

Progress is the movement towards a refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. In the context of progressivism, it refers to the proposition that advancements in technology, science, and social organization have resulted, and by extension wi ...

, before continuing to teach at the university.

In 1898, Moore was given a full-page column in the ''Chicago Vegetarian'', the Chicago Vegetarian Society's journal, which started in 1896; this increased his influence on the society and its overall message. In the same year, Moore started teaching at Crane Technical High School

Richard T. Crane Medical Prep High School (formerly known as Crane Tech Prep or Crane Tech High School) is a public 4–year medical prep high school located in the Near West Side neighborhood of Chicago, Illinois, United States. The school is o ...

; he retained this position for the remainder of his life, while also teaching at other schools in Chicago, including Calumet High School and Hyde Park High School.

In 1899, he married Jennie Louise Darrow (1866–1955), in Racine, Wisconsin

Racine ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Racine County, Wisconsin, United States. It is located on the shore of Lake Michigan at the mouth of the Root River. Racine is situated 22 miles (35 km) south of Milwaukee and approximately 60 ...

. She was an elementary school teacher, a fellow advocate for animal rights

Animal rights is the philosophy according to which many or all sentient animals have moral worth that is independent of their utility for humans, and that their most basic interests—such as avoiding suffering—should be afforded the sa ...

and vegetarianism, and the sister of renowned lawyer Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. He was a leading member of t ...

. The couple soon returned to Chicago.

Later life and career

In 1899, Moore published his first book, ''Better-World Philosophy'', to mixed reviews. In the book, he expressed a longing to change how humans perceive the world and his view that all beings are interconnected. Moore argued that

In 1899, Moore published his first book, ''Better-World Philosophy'', to mixed reviews. In the book, he expressed a longing to change how humans perceive the world and his view that all beings are interconnected. Moore argued that sentience

Sentience is the capacity to experience feelings and sensations. The word was first coined by philosophers in the 1630s for the concept of an ability to feel, derived from Latin '':wikt:sentientem, sentientem'' (a feeling), to distinguish it fro ...

is a requirement for ethics and that because non-human animals have this capacity, ethical consideration should be extended to them. The book was endorsed by Lester F. Ward and David S. Jordan. It also brought Moore to the attention of Henry S. Salt

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

, the founder of the Humanitarian League, and author of '' Animals' Rights Considered in Relation to Social Progress'', who wrote a favorable review of the book. Sustained efforts were made by the League and its allies, including the publisher G. Bell & Sons and ''The Animals' Friend'', to promote and distribute Moore's works in Britain. Following the review, Salt began a correspondence with Moore that developed into a strong friendship.

Moore was a fierce critic of American imperialism

American imperialism refers to the expansion of American political, economic, cultural, and media influence beyond the boundaries of the United States. Depending on the commentator, it may include imperialism through outright military conquest ...

and America's actions in the Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War or Filipino–American War ( es, Guerra filipina-estadounidense, tl, Digmaang Pilipino–Amerikano), previously referred to as the Philippine Insurrection or the Tagalog Insurgency by the United States, was an arm ...

, publishing an article entitled "America's Apostasy", in 1899.

Moore published ''The Universal Kinship

''The Universal Kinship'' is a 1906 book by American zoologist, philosopher, educator and socialist J. Howard Moore. In the book, Moore advocated for a secular Sentiocentrism, sentiocentric philosophy, called the Universal Kinship, which mandated ...

'' in 1906. In the book, he explored the physical, psychical and ethical relationship between humans and other animals, arguing that ''all'' beings possess rights, and that the Golden Rule should be apply to all beings. The book received several favourable reviews. It was endorsed by Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

, Jack London

John Griffith Chaney (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to ...

, Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor "Gene" Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialism, socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five times the candidate ...

, and Mona Caird

Alice Mona Alison Caird (née Alison; 24 May 1854 – 4 February 1932) was an English novelist and essayist. Her feminist writings and views caused controversy in the late 19th century. She also advocated for animal rights and civil liberties, a ...

. Henry S. Salt, later described the book as the "best ever written in the humanitarian cause." Salt and Moore worked together to popularize Moore's doctrine within the humane movement; this was largely unsuccessful.

Moore was a close friend of May Walden Kerr, the wife of Charles H. Kerr

Charles Hope Kerr (April 23, 1860 – June 1, 1944), a son of abolitionists, was a vegetarian and Unitarian in 1886 when he established Charles H. Kerr & Co. in Chicago. His publishing career is noted for his views' leftward progression towar ...

—the publisher of many of Moore's books. Following the Kerr's divorce in 1904, Moore and Walden continued their correspondence and from time to time Moore and his wife vacationed with Walden and her daughter.

In November 1906, Moore's speech "The Cost of a Skin" sparked controversy at the American Humane Association

American Humane (AH) is an organization founded in 1877 committed to ensuring the safety, welfare, and well-being of animals. It was previously called the International Humane Association before changing its name in 1878. In 1940, it became t ...

's convention. In the speech, Moore denounced wearing fur and feathers for fashion as "conscienceless and inhumane". The audience reaction was mixed, with some applauding enthusiastically and others remaining silent; two women left the room before the speech was finished. The speech was later published as a chapter in ''The New Ethics

''The New Ethics'' is a 1907 book by the American zoologist and philosopher J. Howard Moore, in which he advocates for a form of ethics, that he calls the New Ethics, which applies the principle of the Golden Rule—treat others as you would wan ...

'' (1907) and as a pamphlet by the Animals' Friend Society of London.

In 1907, Moore published, to acclaim, ''The New Ethics'', in which he explored the expansion of ethics based on the biological implications of Darwin's theory of evolution. Moore accepted the challenge of changing anthropocentric perceptions, arguing that while such views have developed over the course of generations, both individuals and societies are in a state of constant growth and evolution. He expressed confidence that humans would evolve past their current stage of selfishness.

As well as his work as a high school teacher and author, Moore gave frequent lectures on vegetarianism, the humane treatment of animals, anti-vivisectionism, evolution and ethics. He also authored articles and pamphlets for humane organizations and journals, including the Chicago Vegetarian Society, Humanitarian League, Millennium Guild

Maud Russell Lorraine Freshel (; other married name Sharpe; 1867—1949) was a Boston socialite, designer, and animal rights and vegetarianism activist. She also went by her initials, M. R. L., which she later spelled Emarel.

Life

Maud Russell ...

, Massachusetts SPCA, American Anti-Vivisection Society

The American Anti-Vivisection Society (AAVS) is an organization created with the goal of eliminating a number of different procedures done by medical and cosmetic groups in relation to animal cruelty in the United States. It seeks to help the be ...

, and American Humane Association. Moore additionally wrote in support of the temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emph ...

, and humane education

Humane education is broadly defined as education that nurtures compassion and respect for living beingsUnti, B. & DeRosa, B. (2003). Humane education: Past, present, and future. In D. J. Salem & A. N. Rowam (Eds.), ''The State of the Animals II: 2 ...

.

In 1908, Moore taught courses on elementary zoology, physiographic ecology and the evolution of domestic animals at the University of Chicago for three quarters. In October of that year, Moore endorsed Eugene V. Debs' presidential run, giving a speech in front of the Young People's Socialist League. In the following year, he denounced Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

and his hunting expedition to Africa, describing Roosevelt as having "done more in the last six months to dehumanise mankind than all the humane societies can do to counteract it in years."

In 1909, a law was passed in Illinois prescribing teaching of morals in public schools for 30 minutes each week. Contrary to his fellow teachers, Moore was pleased by the law and began preparing supporting educational materials. He published ''Ethics and Education'', in 1912, as an aid for teachers who were having trouble implementing the new educational requirements. Before the book's publication, Moore sparked controversy when he made available extracts of the book which were critical of the courts and marriage. In an interview, Moore defended the content of the book, inviting the board of education to investigate him if necessary. In the same year, he published ''High-School Ethics: Book One'', which was intended to form the first part of a four-year high school course covering theoretical and practical ethics and covered a variety of topics including the ethics of school life; properly caring for pets; women's rights; birds; where sealskin, ivory and other animal products are sourced from; and good habits. Moore also published a pamphlet titled ''The Ethics of School Life'', which was based on a lesson that Moore gave to high-school students.

Moore wrote to Salt on 25 March 1911 about his experience of depression and a breakdown from overwork. He told Salt that the books he had written might not result in much, but that he felt he put a lot of effort into producing them.

In February 1912, a meeting of the Schoolmasters' Club of Chicago, of which Moore was a member, was disrupted because they did not agree with his views; Moore responded: "I am a radical and a socialist, but I do not allow my radicalism nor my socialism to enter into my teachings."

Moore delivered a speech at the International Anti-vivisection and Animal protection Congress, held in Washington D.C, in 1913; in the speech, he claimed that vivisection and the consumption of meat are both a product of anthropocentrism and that Darwin's ''

In 1909, a law was passed in Illinois prescribing teaching of morals in public schools for 30 minutes each week. Contrary to his fellow teachers, Moore was pleased by the law and began preparing supporting educational materials. He published ''Ethics and Education'', in 1912, as an aid for teachers who were having trouble implementing the new educational requirements. Before the book's publication, Moore sparked controversy when he made available extracts of the book which were critical of the courts and marriage. In an interview, Moore defended the content of the book, inviting the board of education to investigate him if necessary. In the same year, he published ''High-School Ethics: Book One'', which was intended to form the first part of a four-year high school course covering theoretical and practical ethics and covered a variety of topics including the ethics of school life; properly caring for pets; women's rights; birds; where sealskin, ivory and other animal products are sourced from; and good habits. Moore also published a pamphlet titled ''The Ethics of School Life'', which was based on a lesson that Moore gave to high-school students.

Moore wrote to Salt on 25 March 1911 about his experience of depression and a breakdown from overwork. He told Salt that the books he had written might not result in much, but that he felt he put a lot of effort into producing them.

In February 1912, a meeting of the Schoolmasters' Club of Chicago, of which Moore was a member, was disrupted because they did not agree with his views; Moore responded: "I am a radical and a socialist, but I do not allow my radicalism nor my socialism to enter into my teachings."

Moore delivered a speech at the International Anti-vivisection and Animal protection Congress, held in Washington D.C, in 1913; in the speech, he claimed that vivisection and the consumption of meat are both a product of anthropocentrism and that Darwin's ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'' had made any notion of human superiority or uniqueness untenable and ethically indefensible.

Moore opposed the Chicago Board of Education

The Chicago Board of Education serves as the board of education (school board) for the Chicago Public Schools.

The board traces its origins to the Board of School Inspectors, created in 1837.

The board is currently appointed solely by the mayor ...

's move to stop teaching sex hygiene

''Sex Hygiene'' is a 1942 American drama film short directed by John Ford and Otto Brower. The official U.S. military training film is in the instructional social guidance film genre, offering adolescent and adult behavioural advice, medical i ...

, between 1913 and 1914. He wrote a letter to the board in favor of teaching the topic. In January 1914, Moore gave a speech on the topic in Chicago, at Hull House

Hull House was a settlement house in Chicago, Illinois, United States that was co-founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr. Located on the Near West Side of the city, Hull House (named after the original house's first owner Cha ...

. The Board later dropped the change.

In 1914, Moore published ''The Law of Biogenesis: Being Two Lessons on the Origin of Human Nature'', which consisted of lectures developed for lessons at Crane Technical High School, describing the mental and physical features of biogenesis

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from nonliving matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could arise fr ...

—the process of how beings repeat the evolutionary development of their ancestors.

Moore published ''Savage Survivals'' in 1916, a compilation of his lectures delivered at Crane Technical High School. Made-up of five sections covering the evolution and survival of domesticated animals, the savage ancestry of humans and an analysis from an ethical perspective of those surviving traits in humans considered to be civilized.

In June 1916, Moore published an article critical of religion, entitled "The Source of Religion", describing it as "an anachronism today, with our science and understanding". Moore's last book ''The Life of Napoleon'' was finished, but not published.

Death

On June 17, 1916, at the age of 53, Moore died after shooting himself in the head with a revolver on Wooded Island in Jackson Park, Chicago. He had visited the island regularly to observe and study birds. Moore had struggled for many years with a long illness and

On June 17, 1916, at the age of 53, Moore died after shooting himself in the head with a revolver on Wooded Island in Jackson Park, Chicago. He had visited the island regularly to observe and study birds. Moore had struggled for many years with a long illness and chronic pain

Chronic pain is classified as pain that lasts longer than three to six months. In medicine, the distinction between Acute (medicine), acute and Chronic condition, chronic pain is sometimes determined by the amount of time since onset. Two commonly ...

from an abdominal operation, in 1911, for gallstones

A gallstone is a stone formed within the gallbladder from precipitated bile components. The term cholelithiasis may refer to the presence of gallstones or to any disease caused by gallstones, and choledocholithiasis refers to the presence of migr ...

. He had also expressed continuing despondency at human indifference towards the suffering of their fellow animals. In a suicide note

A suicide note or death note is a message left behind by a person who dies or intends to die by suicide.

A study examining Japanese suicide notes estimated that 25–30% of suicides are accompanied by a note. However, incidence rates may depe ...

found on his body by a police officer, he had written:The long struggle is ended. I must pass away. Good-by. Oh, men are so cold and hard and half conscious toward their suffering fellows. Nobody understands. O my mother, and O my little girl! What will become of you? And the poor four-footed! May the long years be merciful! Take me to my river. There, where the wild birds sing and the waters go on and on, alone in my groves, forever. O, Tess, forgive me. O, forgive me, please!Moore's death was ruled a suicide, due to a "temporary fit of insanity". His grief-stricken wife requested that Moore's body be cremated and his ashes sent to Mobile County, Alabama, to be buried in the land near Moore's river. His brother-in-law, Clarence Darrow, who was devastated by Moore's death, delivered a eulogy at his funeral, describing him as a "dead dreamer" who had died while "suffering under a temporary fit of sanity"; the eulogy was later published. Contrary to his wife's request, Moore's remains were returned to his old home near Cawker City, and he was buried in Excelsior Cemetery,

Mitchell County, Kansas

Mitchell County (standard abbreviation: MC) is a county located in the U.S. state of Kansas. As of the 2020 census, the county population was 5,796. The largest city and county seat is Beloit.

History

Early history

For many millennia, the G ...

.

Legacy

An obituary published soon after Moore's death, in the ''Chicago Tribune'', labelled Moore a misanthrope. The obituary in the Humanitarian League's journal ''The Humanitarian'', described Moore, in much more positive terms, as "one of the most devoted and distinguished humanitarians with whom the League has had the honor of being connected." Louis S. Vineburg, who had met Moore in early 1910 at one of Moore's lectures for the Young People's Socialist League, published a personal recollection in the ''International Socialist Review''. Henry S. Salt, Moore's long-time friend, felt that Moore had good reason for his suicide and was scornful of how timidly his death was covered in the majority of English animal advocacy journals. Salt dedicated his 1923 book ''The Story of My Cousins'' to Moore and in his 1930 autobiography ''Company I Have Kept'', he reflected on the strength of their friendship, despite the fact that they never met in person. A selection of Moore's letters to Salt was included in the appendix of the 1992 edition of ''The Universal Kinship'' (edited by Charles R. Magel). Jack London, who had endorsed ''The Universal Kinship'', and in his personal copy of the book marked the passage: "''All beings are ends;'' ''no'' creatures are ''means''. All beings have not equal rights, neither have all men; but ''all have rights''", was greatly moved by Moore's death, writing at the head of a printed copy of Darrow's eulogy for Moore's funeral: "Disappointment like what made Wayland (Appeal to Reason) kill himself and many like me resign." Due to the promotion and dissemination efforts of the Humanitarian League, G. Bell & Sons and ''The Animals Friend'', Moore is considered to have possessed "a wider and readier acceptance of his views" in Britain than in the United States.Contemporary reception

Moore has been recognized as an early, but neglected, advocate forethical vegetarianism

Conversations regarding the ethics of eating meat are focused on whether or not it is moral to eat non-human animals. Ultimately, this is a debate that has been ongoing for millennia, and it remains one of the most prominent topics in food ethics ...

; Rod Preece described Moore's ethical vegetarian advocacy as "ahead of his time", as it appears to not have had "any direct influence on the American intelligentsia." Preece also highlighted Moore, along with Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Word ...

and Henry S. Salt, as writers before World War I, who connected Darwinian evolution with animal ethics

Animal ethics is a branch of ethics which examines human-animal relationships, the moral consideration of animals and how nonhuman animals ought to be treated. The subject matter includes animal rights, animal welfare, animal law, speciesism, ani ...

.

Moore's ethical approach has been compared to Albert Schweitzer

Ludwig Philipp Albert Schweitzer (; 14 January 1875 – 4 September 1965) was an Alsatian-German/French polymath. He was a theologian, organist, musicologist, writer, humanitarian, philosopher, and physician. A Lutheran minister, Schwei ...

and Peter Singer

Peter Albert David Singer (born 6 July 1946) is an Australian moral philosopher, currently the Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at Princeton University. He specialises in applied ethics and approaches ethical issues from a secular, ...

, with Moore's views identified as anticipating Singer's analysis of speciesism

Speciesism () is a term used in philosophy regarding the treatment of individuals of different species. The term has several different definitions within the relevant literature. A common element of most definitions is that speciesism involves t ...

. Donna L. Davey asserts that: "The recurring themes of Moore's works are today the foundation of the modern animal-rights movement." James J. Copp describes Moore as "one of the leading activists in the ethical treatment of animals in the early twentieth century." Bernard Unti argues that Moore's ''The Universal Kinship'' sets him apart as the "first American intellectual in the realm of animal rights." Animal rights activist Henry Spira

Henry Spira (19 June 1927 – 12 September 1998) was an American activist for socialism and animal rights, who is regarded by some as one of the most effective animal advocates of the 20th century.Singer, in Spira and Singer 2006, pp. 214–215.

...

cited Moore as an example of a leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

who wasn't uncomfortable about advocating for animal rights.

Simon Brooman and Debbie Legge argue that Moore "correctly predicted that the way in which animals were treated in his time would come to be regarded as purely anthropocentric exercises of human dominion to be replaced, in large part, by a new philosophy which recognises the 'unity and consanguinity' of all organic life." The environmental historian Roderick Nash

Roderick Frazier Nash is a professor emeritus of history and environmental studies at the University of California Santa Barbara. He was the first person to descend the Tuolumne River using a raft.

Scholarly biography

Nash received his Bache ...

argues that both Moore and Edward Payson Evans

Edward Payson Evans (December 8, 1831 – March 6, 1917) was an American scholar, linguist and early advocate for animal rights. He is best known for his 1906 book on animal trials, ''The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals.'' ...

, "deserve more recognition than they have received as the first professional philosophers in the United States to look beyond anthropocentrism."

Gary K. Jarvis argues that unlike the British humanitarian movement, the American movement had never successfully taken hold and that following Ernest Crosby's death, in 1907, Moore had represented the remainder of the movement, which meant that his death effectively ended it; Jarvis also contends that World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

was what ultimately brought the end to the wider humanitarian movement. Jarvis also challenges the labelling of Moore as a misanthrope, arguing that Moore's criticism of anthropocentrism and Western civilization for promoting it was incorrectly perceived as misanthropic.

Selections of Moore's works were included in Jon Wynne-Tyson

Jon Linden Wynne-Tyson (6 July 1924 – 26 March 2020) was an English author, publisher, Walters, Kerry S., Portmess, Lisa, 1999, ''Ethical Vegetarianism: From Pythagoras to Peter Singer'', SUNY Press, p. 233, . Quaker, activist and pacifist, w ...

's 1985 book, ''The Extended Circle: A Dictionary of Humane Thought''. Mark Gold cited Moore and Henry S. Salt as the two main inspirations for his 1995 book, ''Animal Rights: Extending the Circle of Compassion''.

Criticism

Moore's last published book, ''Savage Survivals'', has been criticized as an example of scientific racism by the prehistoric archaeologistRobin Dennell

Robin W. Dennell (born 1947) is a British prehistoric archaeologist specialising in early hominin expansions out of Africa and the Palaeolithic of Pakistan and China. He is Professor Emeritus of Human Origins of the University of Sheffield, and ...

. Mark Pittenger argues that Moore's racism was influenced by Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest" ...

's ''The Principles of Sociology'' and that similar views were held by contemporary American socialists. Gary K. Jarvis describes Moore as a critic of social Darwinism, asserting: "Moore argued that social Darwinists derived their beliefs from the worst examples that evolution offered, not the best."

Selected publications

Articles

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Books

* * * * * * * * *Pamphlets

* ''A Race of Somnambulists'' (Mount Lebanon, N.Y.: Lebanon Press, 1890) * '' Why I Am a Vegetarian: An Address Delivered before the Chicago Vegetarian Society'' (Chicago: Frances L. Dusenberry, 1895) * ''America's Apostasy'' (Chicago: The Ward Waugh Company, 1899) * ''Clerical Sportsmen: A Protest Against the Vacation Pastime of Ministers of the Gospel'' (Chicago: Chicago Vegetarian) *The Cost of a Skin

' (London:

Animal Defence and Anti-Vivisection Society

The Animal Defence and Anti-Vivisection Society (ADAVS) was an animal rights advocacy organisation, co-founded in England, in 1903, by the animal rights advocates Lizzy Lind af Hageby, a Swedish-British feminist, and the English peeress Nina Do ...

)

* ''The Logic of Humanitarianism''

* ''Humane Teaching in Schools'' (London: Animals' Friend Society, 1911)

* The Care of Illegitimate Children in Chicago

' (Chicago: Juvenile Protective Association of Chicago, 1912) * ''The Ethics of School Life: A Lesson Given at the Crane Technical High School, Chicago, in Accordance with the Law Requiring the Teaching of Morals in the Public Schools of Illinois'' (London: G. Bell & Sons, 1912)

Translations

* * * * * * * * * * *See also

*List of animal rights advocates

Advocates of animal rights support the philosophy of animal rights. They believe that many or all sentient animals have moral worth that is independent of their utility for humans, and that their most basic interests—such as in avoiding suff ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* * * * * * *External links

* * *J. Howard Moore

at Animal Rights Library

at The Clarence Darrow Digital Collection

Photograph of J. Howard Moore and his wife Jennie

{{DEFAULTSORT:Moore, J. Howard 1862 births 1916 suicides 19th-century American biographers 19th-century American educators 19th-century American essayists 19th-century American journalists 19th-century American male singers 19th-century American singers 19th-century American male writers 19th-century American non-fiction writers 19th-century American philosophers 19th-century American zoologists 19th-century social scientists 20th-century American biographers 20th-century American educators 20th-century American essayists 20th-century American journalists 20th-century American male singers 20th-century American singers 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American philosophers 20th-century American zoologists 20th-century social scientists American animal rights activists American animal rights scholars American atheist writers American atheists American columnists American education writers American ethicists American eugenicists American former Christians American humanitarians American male non-fiction writers American newspaper reporters and correspondents American pamphleteers American public speakers American science writers American socialists American suffragists American temperance activists American vegetarianism activists Animal ethicists Anti-imperialism Anti-vivisectionists Birdwatchers Burials in Kansas Drake University alumni Educational reformers Education writers Injuries from lightning strikes Oskaloosa College alumni People from Rockville, Indiana Public orators Sentientists Schoolteachers from Indiana Sex education advocates Suicides by firearm in Illinois University of Chicago alumni University of Chicago faculty University of Wisconsin people Utilitarians