John Harvey Kellogg (February 26, 1852 – December 14, 1943) was an American

medical doctor

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

, nutritionist, inventor, health activist,

eugenicist

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

, and businessman. He was the director of the

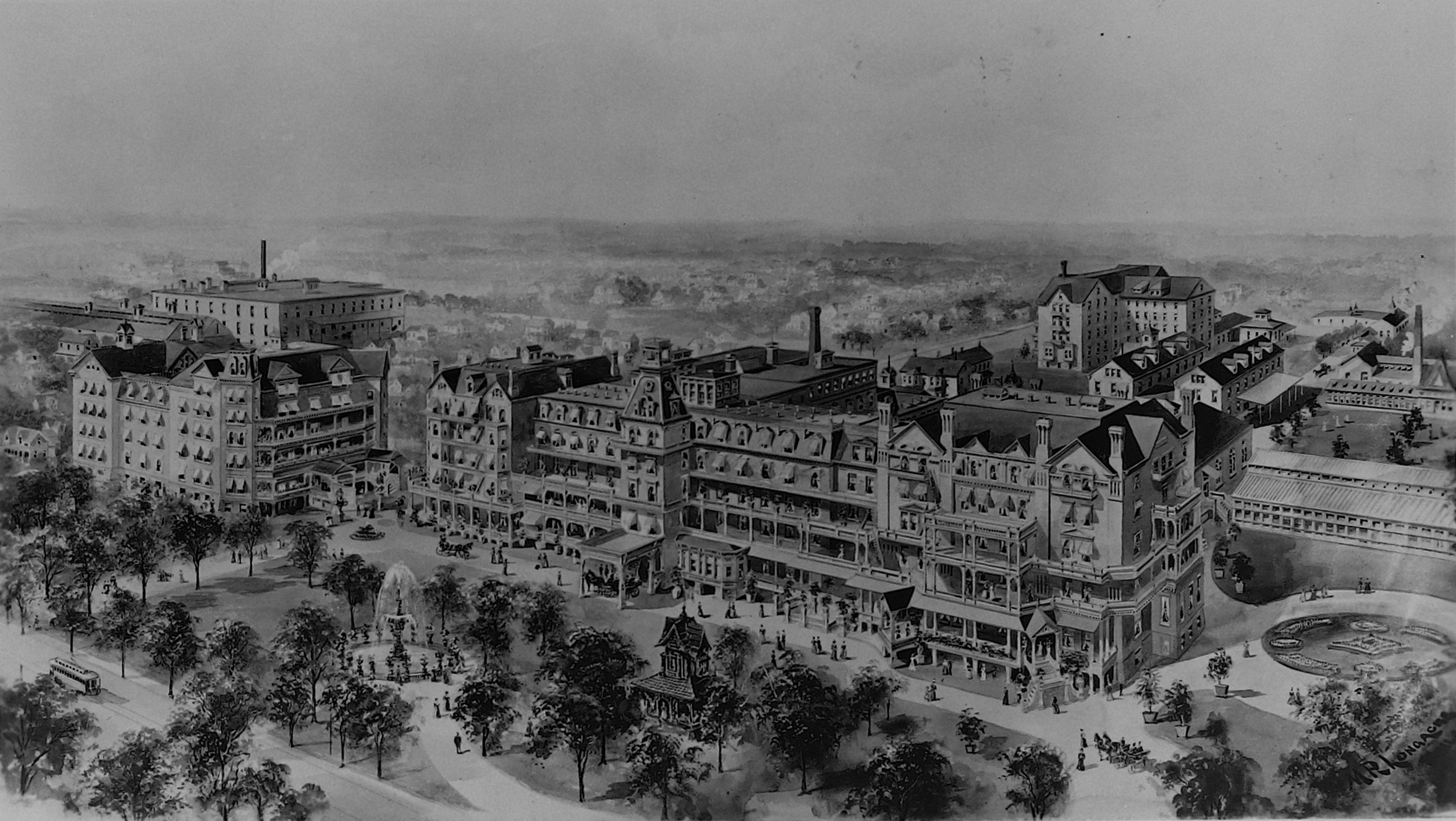

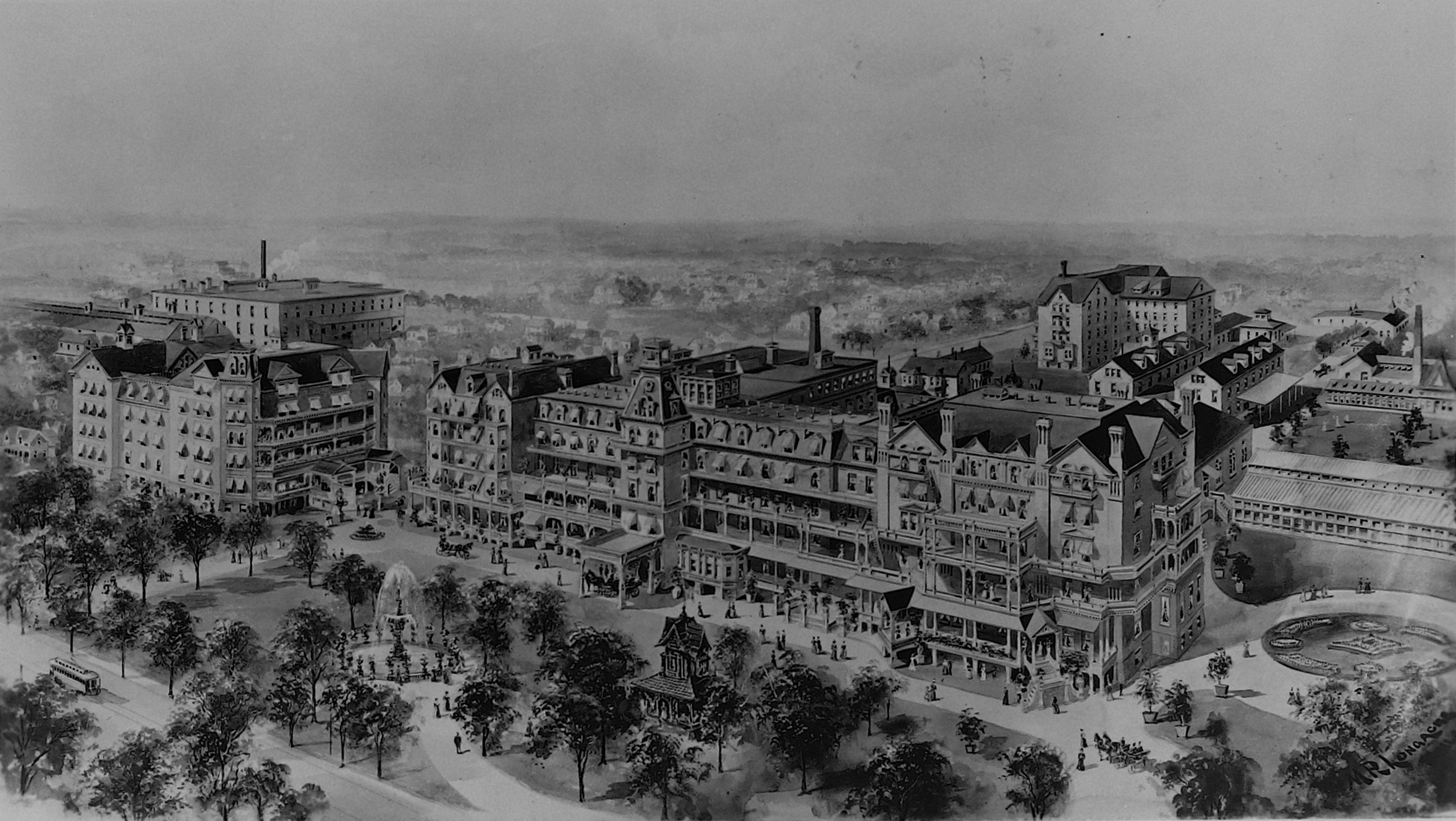

Battle Creek Sanitarium

The Battle Creek Sanitarium was a world-renowned health resort in Battle Creek, Michigan, United States. It started in 1866 on health principles advocated by the Seventh-day Adventist Church and from 1876 to 1943 was managed by Dr. John H ...

in

Battle Creek, Michigan

Battle Creek is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan, in northwest Calhoun County, Michigan, Calhoun County, at the confluence of the Kalamazoo River, Kalamazoo and Battle Creek River, Battle Creek rivers. It is the principal city of the Battle C ...

. The sanitarium was founded by members of the

Seventh-Day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbath, and ...

. It combined aspects of a European spa, a

hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy, formerly called hydropathy and also called water cure, is a branch of alternative medicine (particularly naturopathy), occupational therapy, and physiotherapy, that involves the use of water for pain relief and treatment. The term ...

institution, a hospital and high-class hotel. Kellogg treated the rich and famous, as well as the poor who could not afford other hospitals. Several

popular misconceptions falsely attribute various cultural practices, inventions, and historical events to Kellogg.

Theologically, his views went against many of the traditional tenets of

Nicene Christianity

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is a ...

. As

Seventh-Day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbath, and ...

beliefs shifted towards

orthodox Trinitarianism during the 1890s, Adventists within the denominations were "unable to accommodate the essentially

liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

understanding of Christianity" exhibited by Kellogg, viewing his

theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

as

pantheistic

Pantheism is the belief that reality, the universe and the cosmos are identical with divinity and a supreme supernatural being or entity, pointing to the universe as being an immanent creator deity still expanding and creating, which has ex ...

and unorthodox.

Disagreements with other members of the church led to a major schism within the denomination: he was disfellowshipped in 1907, but continued to follow many Adventist beliefs and directed the sanitarium until his death in 1943. Kellogg also helped to establish the

American Medical Missionary College

American Medical Missionary College was a private Seventh-day Adventist college in Battle Creek, Michigan. It grew out of classes offered at the Battle Creek Sanitarium. It existed from 1895 until 1910, with preclinical instruction in Battle Cr ...

in 1895. The college operated independently until 1910, when it merged with

Illinois State University

Illinois State University (ISU) is a public university in Normal, Illinois. Founded in 1857 as Illinois State Normal University, it is the oldest public university in Illinois. The university emphasizes teaching and is recognized as one of th ...

.

Kellogg was a major leader in progressive health reform, particularly in the second phase of the

clean living movement

In the history of the United States, a clean living movement is a period of time when a surge of health-reform crusades erupts into the popular consciousness. This results in individual, or group reformers such as the anti-tobacco or alcohol coal ...

.

He wrote extensively on science and health. His approach to "biologic living" combined scientific knowledge with Adventist beliefs, promoting health reform, and

temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

. His promotion of developing

anaphrodisiac

An anaphrodisiac (also antaphrodisiac or antiaphrodisiac) is a substance that quells or blunts the libido. It is the opposite of an aphrodisiac, something that enhances sexual appetite. The word ''anaphrodisiac'' comes from the Greek privative p ...

foods was based on these beliefs.

Many of the

vegetarian

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the consumption of meat (red meat, poultry, seafood, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slaughter.

Vegetarianism m ...

foods that Kellogg developed and offered his patients were publicly marketed: Kellogg's brother,

Will Keith Kellogg

William Keith Kellogg (April 7, 1860 – October 6, 1951), generally referred to as W.K. Kellogg, was an American industrialist in food manufacturing, best known as the founder of the Kellogg's, Kellogg Company, which produces a wide variety of ...

, is best known today for the invention of the

breakfast cereal

Cereal, formally termed breakfast cereal (and further categorized as cold cereal or warm cereal), is a traditional breakfast food made from processed cereal grains. It is traditionally eaten as part of breakfast, or a snack food, primarily in ...

corn flakes

Corn flakes, or cornflakes, are a breakfast cereal made from toasting flakes of corn (maize). The cereal, originally made with wheat, was created by Will Kellogg in 1894 for patients at the Battle Creek Sanitarium where he worked with his bro ...

.

This creation of the modern breakfast cereal changed "the American breakfast landscape forever."

As an early proponent of the

germ theory of disease

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can lead to disease. These small organisms, too small to be seen without magnification, invade h ...

, Kellogg was well ahead of his time in relating

intestinal flora

Gut microbiota, gut microbiome, or gut flora, are the microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses that live in the digestive tracts of animals. The gastrointestinal metagenome is the aggregate of all the genomes of the gut mi ...

and the presence of bacteria in the intestines to health and disease. The sanitarium approached treatment in a

holistic

Holism () is the idea that various systems (e.g. physical, biological, social) should be viewed as wholes, not merely as a collection of parts. The term "holism" was coined by Jan Smuts in his 1926 book ''Holism and Evolution''."holism, n." OED Onl ...

manner, actively promoting vegetarianism, nutrition, the use of

enema

An enema, also known as a clyster, is an injection of fluid into the lower bowel by way of the rectum.Cullingworth, ''A Manual of Nursing, Medical and Surgical'':155 The word enema can also refer to the liquid injected, as well as to a device ...

s to clear "intestinal flora", exercise, sun-bathing, and

hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy, formerly called hydropathy and also called water cure, is a branch of alternative medicine (particularly naturopathy), occupational therapy, and physiotherapy, that involves the use of water for pain relief and treatment. The term ...

, as well as the abstention from smoking tobacco, drinking alcoholic beverages, and sexual activity.

Kellogg dedicated the last 30 years of his life to promoting eugenics. He co-founded the

Race Betterment Foundation

The Race Betterment Foundation was a eugenics and racial hygiene organization founded in 1914 at Battle Creek, Michigan by John Harvey Kellogg due to his concerns about what he perceived as "race degeneracy". The foundation supported conferences ...

, co-organized several National Conferences on Race Betterment and attempted to create a 'eugenics registry'. Alongside discouraging 'racial mixing', Kellogg was in favor of sterilizing 'mentally defective persons', promoting a eugenics agenda while working on the Michigan Board of Health and helping to enact authorization to sterilize those deemed 'mentally defective' into state laws during his tenure.

Personal life

John Harvey Kellogg was born in

Tyrone, Michigan, on February 26, 1852, to John Preston Kellogg (1806–1881) and his second wife Ann Janette Stanley (1824–1893).

[ His father, John Preston Kellogg, was born in Hadley, Massachusetts; his ancestry can be traced back to the founding of Hadley, Massachusetts, where a great-grandfather operated a ferry.]Will Keith Kellogg

William Keith Kellogg (April 7, 1860 – October 6, 1951), generally referred to as W.K. Kellogg, was an American industrialist in food manufacturing, best known as the founder of the Kellogg's, Kellogg Company, which produces a wide variety of ...

.Baptists

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

, the Congregationalist Church

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

, and finally the Seventh-day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbath, and ...

.Ellen G. White

Ellen Gould White (née Harmon; November 26, 1827 – July 16, 1915) was an American woman author and co-founder of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Along with other Adventist leaders such as Joseph Bates and her husband James White, she wa ...

and her husband James Springer White

James Springer White (August 4, 1821 – August 6, 1881), also known as Elder White, was a co-founder of the Seventh-day Adventist Church and husband of Ellen G. White. In 1849 he started the first Sabbatarian Adventist periodical entitled '' Th ...

to relocate to Battle Creek, Michigan

Battle Creek is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan, in northwest Calhoun County, Michigan, Calhoun County, at the confluence of the Kalamazoo River, Kalamazoo and Battle Creek River, Battle Creek rivers. It is the principal city of the Battle C ...

, with their publishing business, in 1855.broom

A broom (also known in some forms as a broomstick) is a cleaning tool consisting of usually stiff fibers (often made of materials such as plastic, hair, or corn husks) attached to, and roughly parallel to, a cylindrical handle, the broomstick. I ...

factory.Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messi ...

of Christ was imminent, and that formal education of their children was therefore unnecessary. Originally a sickly child, John Harvey Kellogg attended Battle Creek public schools only briefly, from ages 9–11. He left school to work sorting brooms in his father's broom factory. Nonetheless, he read voraciously and acquired a broad but largely self-taught education. At age 12, John Harvey Kellogg was offered work by the Whites. He became one of their protégés,printer's devil

A printer's devil was a young apprentice in a printing establishment who performed a number of tasks, such as mixing tubs of ink and fetching type. Notable writers including Ambrose Bierce, Benjamin Franklin, Walt Whitman, and Mark Twain served ...

, and eventually doing proofreading and editorial work. Kellogg hoped to become a teacher, and at age 16 taught a district school in Hastings, Michigan.

Kellogg hoped to become a teacher, and at age 16 taught a district school in Hastings, Michigan.Michigan State Normal School

Eastern Michigan University (EMU, Eastern Michigan or simply Eastern), is a public research university in Ypsilanti, Michigan. Founded in 1849 as Michigan State Normal School, the school was the fourth normal school established in the United Sta ...

.Edson White

James Edson White (28 July 1849 – 3 June 1928), known as "Edson", was an author, publisher and the second son of two of the pioneers of the Seventh-day Adventist Church – James White and Ellen G. White.

In 1870 he married Emma McDearmon, bu ...

, William C. White, and Jennie Trembley, as students in a six-month medical course at Russell Trall's Hygieo-Therapeutic College in Florence Township, New Jersey

Florence Township is a township in Burlington County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the township's population was 12,109, reflecting an increase of 1,363 (+12.7%) from the 10,746 counted in the 2000 Census, ...

. Their goal was to develop a group of trained doctors for the Adventist-inspired Western Health Reform Institute in Battle Creek.University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

and the Bellevue Hospital Medical College

NYU Grossman School of Medicine is a medical school of New York University, a private research university in New York City. It was founded in 1841 and is one of two medical schools of the university, with the other being the Long Island School of ...

in New York City. He graduated in 1875 with a medical degree.adopt

Adoption is a process whereby a person assumes the parenting of another, usually a child, from that person's biological or legal parent or parents. Legal adoptions permanently transfer all rights and responsibilities, along with filiation, from ...

ing 8 of them, before Ella died in 1920.Oglethorpe University

Oglethorpe University is a private college in Brookhaven, Georgia. It was chartered in 1835 and named in honor of General James Edward Oglethorpe, founder of the Colony of Georgia.

History

Oglethorpe University was chartered in 1834 in Mid ...

.

Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

-winning historian Will Durant

William James Durant (; November 5, 1885 – November 7, 1981) was an American writer, historian, and philosopher. He became best known for his work '' The Story of Civilization'', which contains 11 volumes and details the history of eastern a ...

, who had been a vegetarian since the age of 18, called Dr. Kellogg "his old mentor", and said that Dr. Kellogg, more than any other person since his high school days, had influenced his life.

Kellogg died on December 14, 1943, in Battle Creek, Michigan

Battle Creek is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan, in northwest Calhoun County, Michigan, Calhoun County, at the confluence of the Kalamazoo River, Kalamazoo and Battle Creek River, Battle Creek rivers. It is the principal city of the Battle C ...

.

Theological views

Kellogg was brought up in the Seventh-day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbath, and ...

from childhood. Selected as a protégé of the Whites and trained as a doctor, Kellogg held a prominent role as a speaker at church meetings.

Harmony of science and the Bible

Kellogg defended "the harmony of science and the Bible" throughout his career, but he was active at a transitional time, when both science and medicine were becoming increasingly secularized

In sociology, secularization (or secularisation) is the transformation of a society from close identification with religious values and institutions toward non-religious values and secular institutions. The ''secularization thesis'' expresses the ...

. White and others in the Adventist ministry worried that Kellogg's students and staff were in danger of losing their religious beliefs, while Kellogg felt that many ministers failed to recognize his expertise and the importance of his medical work. There were ongoing tensions between his authority as a doctor, and their authority as ministers.panentheistic

Panentheism ("all in God", from the Greek grc, πᾶν, pân, all, label=none, grc, ἐν, en, in, label=none and grc, Θεός, Theós, God, label=none) is the belief that the divine intersects every part of the universe and also extends bey ...

tendencies (Everything is in God).

Pantheism Crisis

His theological views went against many of the traditional tenets of Nicene Christianity

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is a ...

. As Seventh-Day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbath, and ...

beliefs shifted towards orthodox Trinitarianism during the 1890s, Adventists within the denominations were "unable to accommodate the essentially liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

understanding of Christianity" exhibited by Kellogg, viewing his theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

as pantheistic

Pantheism is the belief that reality, the universe and the cosmos are identical with divinity and a supreme supernatural being or entity, pointing to the universe as being an immanent creator deity still expanding and creating, which has ex ...

and unorthodox.Ellen G. White

Ellen Gould White (née Harmon; November 26, 1827 – July 16, 1915) was an American woman author and co-founder of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Along with other Adventist leaders such as Joseph Bates and her husband James White, she wa ...

, who had proclaimed that a cleansing sword of fire was poised over the increasingly "worldly" and business-oriented Battle Creek, was against rebuilding the large institution.

Disfellowship

Kellogg used proceeds from his book ''The Living Temple'' to help pay the costs of reconstruction. The book's printing was opposed by a commission of the General Council of the Adventists after W. W. Prescott

William Warren Prescott (1855–1944) was an administrator, educator, and scholar in the early Seventh-day Adventist Church.

Biography

Prescott's parents were part of the Millerites, Millerite movement.

W. W. Prescott graduated from Dartmouth ...

, one of the four members of the commission, argued that it was heretical. When Kellogg arranged to print it privately, the book went through its own trial by fire: on December 30, 1902, fire struck the ''Herald'' where the book was typeset and ready to print.

Battle Creek Sanitarium

Kellogg was a Seventh-day Adventist

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is an Adventism, Adventist Protestantism, Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the Names of the days of the week#Numbered days of the week, seventh day of the ...

until mid-life, and gained fame while being the chief medical officer of the Battle Creek Sanitarium, which was owned and operated by the Seventh-day Adventist Church. The sanitarium was operated based on the church's health principles. Adventists believe in promoting a vegetarian diet, abstinence from alcohol and tobacco, and a regimen of exercise, all of which Kellogg followed. He is remembered as an advocate of vegetarianism and wrote in favor of it, even after leaving the Adventist Church. His dietary advice in the late 19th century discouraged meat-eating, but not emphatically so. His development of a bland diet was driven in part by the Adventist goal of reducing sexual stimulation.corn flakes

Corn flakes, or cornflakes, are a breakfast cereal made from toasting flakes of corn (maize). The cereal, originally made with wheat, was created by Will Kellogg in 1894 for patients at the Battle Creek Sanitarium where he worked with his bro ...

, Kellogg also invented a process for making peanut butter

Peanut butter is a food paste or spread made from ground, dry-roasted peanuts. It commonly contains additional ingredients that modify the taste or texture, such as salt, sweeteners, or emulsifiers. Peanut butter is consumed in many countri ...

intestinal flora

Gut microbiota, gut microbiome, or gut flora, are the microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses that live in the digestive tracts of animals. The gastrointestinal metagenome is the aggregate of all the genomes of the gut mi ...

. He posited that bacteria in the intestines can either help or hinder the body; that pathogenic bacteria produce toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring organic poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. Toxins occur especially as a protein or conjugated protein. The term toxin was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849– ...

s during the digestion of protein which poison the blood; that a poor diet favors harmful bacteria that can then infect other tissues in the body; that the intestinal flora is changed by diet and is generally changed for the better by a well-balanced vegetarian diet favoring low-protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

, laxative

Laxatives, purgatives, or aperients are substances that loosen stools and increase bowel movements. They are used to treat and prevent constipation.

Laxatives vary as to how they work and the side effects they may have. Certain stimulant, lubri ...

, and high-fiber

Fiber or fibre (from la, fibra, links=no) is a natural or artificial substance that is significantly longer than it is wide. Fibers are often used in the manufacture of other materials. The strongest engineering materials often incorporate ...

foods. He recommended various regimens of specific foods designed to heal particular ailments.

Kellogg further believed that natural changes in intestinal flora could be sped by enemas seeded with favorable bacteria. He advocated the frequent use of an enema machine to cleanse the bowel with several gallons of water. Water enemas were followed by the administration of a pint of yogurt

Yogurt (; , from tr, yoğurt, also spelled yoghurt, yogourt or yoghourt) is a food produced by bacterial Fermentation (food), fermentation of milk. The bacteria used to make yogurt are known as ''yogurt cultures''. Fermentation of sugars in t ...

– half was eaten, the other half was administered by enema, "thus planting the protective germs where they are most needed and may render most effective service." The yogurt served to replace the intestinal flora of the bowel, creating what Kellogg claimed was a squeaky-clean intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans ...

.

Sanitarium visitors also engaged in breathing exercises and mealtime marches, to promote proper

Sanitarium visitors also engaged in breathing exercises and mealtime marches, to promote proper digestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food molecules into small water-soluble food molecules so that they can be absorbed into the watery blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intest ...

of food throughout the day. Because Kellogg was a staunch supporter of phototherapy

Light therapy, also called phototherapy or bright light therapy is intentional daily exposure to direct sunlight or similar-intensity artificial light in order to treat medical disorders, especially seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and circadi ...

, the sanitarium made use of artificial sunbaths.circumcision

Circumcision is a surgical procedure, procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin ...

as a remedy for "local uncleanliness" (which he thought could lead to "unchastity"), phimosis

Phimosis (from Greek φίμωσις ''phimōsis'' 'muzzling'.) is a condition in which the foreskin of the penis cannot stretch to allow it to be pulled back past the glans. A balloon-like swelling under the foreskin may occur with urination. In ...

, and "in small boys", masturbation

Masturbation is the sexual stimulation of one's own genitals for sexual arousal or other sexual pleasure, usually to the point of orgasm. The stimulation may involve hands, fingers, everyday objects, sex toys such as vibrators, or combinatio ...

.[''Plain Facts for Old And Young'', 1910 ed.]

p. 325

/ref>

He had many notable patients, such as former president William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, composer and pianist Percy Grainger

Percy Aldridge Grainger (born George Percy Grainger; 8 July 188220 February 1961) was an Australian-born composer, arranger and pianist who lived in the United States from 1914 and became an American citizen in 1918. In the course of a long an ...

, arctic explorers Vilhjalmur Stefansson

Vilhjalmur Stefansson (November 3, 1879 – August 26, 1962) was an Arctic explorer and ethnologist. He was born in Manitoba, Canada.

Early life

Stefansson, born William Stephenson, was born at Arnes, Manitoba, Canada, in 1879. His parents had ...

and Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen bega ...

, world travellers Richard Halliburton

Richard Halliburton (January 9, 1900 – Declared death in absentia, presumed dead after March 24, 1939) was an American travel writing, travel writer and adventurer who swam the length of the Panama Canal and paid the lowest toll in its hi ...

and Lowell Thomas

Lowell Jackson Thomas (April 6, 1892 – August 29, 1981) was an American writer, actor, broadcaster, and traveler, best remembered for publicising T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia). He was also involved in promoting the Cinerama widescreen ...

, aviator Amelia Earhart

Amelia Mary Earhart ( , born July 24, 1897; disappeared July 2, 1937; declared dead January 5, 1939) was an American aviation pioneer and writer. Earhart was the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. She set many oth ...

, economist Irving Fisher

Irving Fisher (February 27, 1867 – April 29, 1947) was an American economist, statistician, inventor, eugenicist and progressive social campaigner. He was one of the earliest American neoclassical economists, though his later work on debt def ...

, Nobel prize winning playwright George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, actor and athlete Johnny Weissmuller

Johnny Weissmuller (born Johann Peter Weißmüller; June 2, 1904 – January 20, 1984) was an American Olympic swimmer, water polo player and actor. He was known for having one of the best competitive swimming records of the 20th century. H ...

, founder of the Ford Motor Company Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that mi ...

, inventor Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventio ...

, African-American activist Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth (; born Isabella Baumfree; November 26, 1883) was an American abolitionist of New York Dutch heritage and a women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to f ...

, and actress Sarah Bernhardt

Sarah Bernhardt (; born Henriette-Rosine Bernard; 22 or 23 October 1844 – 26 March 1923) was a French stage actress who starred in some of the most popular French plays of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including '' La Dame Aux Camel ...

.

Patents and inventions

Foods

John Harvey Kellogg developed and marketed a wide variety of vegetarian foods. Many of them were meant to be suitable for an invalid diet, and were intentionally made easy to chew and to digest. Starchy foods such as grains were ground and baked, to promote the conversion of starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human diets ...

into dextrin

Dextrins are a group of low-molecular-weight carbohydrates produced by the hydrolysis of starch and glycogen. Dextrins are mixtures of polymers of D-glucose units linked by α-(1→4) or α-(1→6) glycosidic bonds.

Dextrins can be produced from ...

. Nuts were ground and boiled or steamed.Ellen G. White

Ellen Gould White (née Harmon; November 26, 1827 – July 16, 1915) was an American woman author and co-founder of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Along with other Adventist leaders such as Joseph Bates and her husband James White, she wa ...

and Sylvester Graham who recommended a diet of bland foods to minimize excitement, sexual arousal, and masturbation.

Breakfast cereals

Around 1877, John H. Kellogg began experimenting to produce a softer breakfast food, something easy to chew. He developed a dough that was a mixture of wheat,

Around 1877, John H. Kellogg began experimenting to produce a softer breakfast food, something easy to chew. He developed a dough that was a mixture of wheat, oats

The oat (''Avena sativa''), sometimes called the common oat, is a species of cereal grain grown for its seed, which is known by the same name (usually in the plural, unlike other cereals and pseudocereals). While oats are suitable for human con ...

, and corn. It was baked at high temperatures for a long period of time, to break down or "dextrinize" starch molecules in the grain. After it cooled, Kellogg broke the bread into crumbs. The cereal was originally marketed under the name "Granula

Granula was the first manufactured breakfast cereal. It was invented by James Caleb Jackson in 1863. Granula could be described as being a larger and tougher version of the somewhat similar later cereal Grape-Nuts. Granula, however, consisted prim ...

" but this led to legal problems with James Caleb Jackson

James Caleb Jackson (March 28, 1811 – July 11, 1895) was an American nutritionist and the inventor of the first dry, whole grain breakfast cereal which he called Granula. His views influenced the health reforms of Ellen G. White, a founder of ...

who already sold a wheat cereal under that name. In 1881, under threat of a lawsuit by Jackson, Kellogg changed the sanitarium cereal's name to "Granola".corn flakes

Corn flakes, or cornflakes, are a breakfast cereal made from toasting flakes of corn (maize). The cereal, originally made with wheat, was created by Will Kellogg in 1894 for patients at the Battle Creek Sanitarium where he worked with his bro ...

. The development of the flaked cereal in 1894 has been variously described by those involved: Ella Eaton Kellogg, John Harvey Kellogg, his younger brother Will Keith Kellogg, and other family members. There is considerable disagreement over who was involved in the discovery, and the role that they played. According to some accounts, Ella suggested rolling out the dough into thin sheets, and John developed a set of rollers for the purpose. According to others, John had the idea in a dream, and used equipment in his wife's kitchen to do the rolling. It is generally agreed that upon being called out one night, John Kellogg left a batch of wheat-berry dough behind. Rather than throwing it out the next morning, he sent it through the rollers and was surprised to obtain delicate flakes, which could then be baked. Will Kellogg was tasked with figuring out what had happened, and recreating the process reliably. Ella and Will were often at odds, and their versions of the story tend to minimize or deny each other's involvement, while emphasizing their own part in the discovery.[John Harvey Kellogg, U.S. Patent no. , ''Flaked Cereals and Process of Preparing Same'', filed May 31, 1895, issued April 14, 1896.] Will later insisted that he, not Ella, had worked with John, and repeatedly asserted that he should have received more credit than he was given for the discovery of the flaked cereal.Kellogg Company

The Kellogg Company, doing business as Kellogg's, is an American multinational food manufacturing company headquartered in Battle Creek, Michigan, United States. Kellogg's produces cereal and convenience foods, including crackers and toas ...

, while John was denied the right to use the Kellogg name for his cereals.Christian Scientists

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

whom he credited with his successful treatment. He settled in Battle Creek, opened his own sanitarium, the LaVita Inn, in March 1892, and founded his own dry foods company, Post Holdings

Post Holdings (officially Post Holdings, Inc.) is an American consumer packaged goods holding company headquartered in St Louis, Missouri with businesses operating in the center-of-the-store, refrigerated, foodservice and food ingredient categori ...

.Postum

Postum () is a powdered roasted grain beverage popular as a coffee substitute. The caffeine-free beverage was created by Post Cereal Company founder C. W. Post in 1895 and marketed as a healthier alternative to coffee. Post was a student of Jo ...

coffee substitute in 1895.Grape-Nuts

Grape-Nuts is a brand of breakfast cereal made from flour, salt and dried yeast, developed in 1897 by C. W. Post, a former patient and later competitor of the 19th-century breakfast food innovator Dr. John Harvey Kellogg. Post's original product ...

breakfast cereal, a mixture of yeast, barley and wheat, in January 1898.Post Toasties

Post Toasties was an early American breakfast cereal made by Post Foods. It was named for its originator, C. W. Post, and intended as the Post version of corn flakes.

Post Toasties were originally sold as Elijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִ� ...

Double-Crisp Corn Flakes, and marketing it as a direct competitor to Kellogg's Corn Flakes.National Inventors Hall of Fame

The National Inventors Hall of Fame (NIHF) is an American not-for-profit organization, founded in 1973, which recognizes individual engineers and inventors who hold a U.S. patent of significant technology. Besides the Hall of Fame, it also opera ...

in 2006 for the discovery of tempering and the invention of the first dry flaked breakfast cereal, which "transformed the typical American breakfast".

Peanut butter

John H. Kellogg is one of several people who have been credited with the invention of peanut butter.Marcellus Gilmore Edson

Marcellus Gilmore Edson (February 7, 1849 – March 6, 1940) was a Canadian chemist and pharmacist. In 1884, he patented a way to make peanut paste, an early version of peanut butter.

Biography

Marcellus Gilmore Edson was born at Bedford in Q ...

(1849–1940) of Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

, Canada obtained a patent for the "Manufacture of peanut-candy", combining 1 part of a "flavoring paste" made from roasted peanuts with 7 parts of sugar.

By 1894, George A. Bayle of St. Louis was selling a "Cheese Nut" snack food containing peanuts and cheese; a peanut-only version was apparently more successful.George Washington Carver

George Washington Carver ( 1864 – January 5, 1943) was an American agricultural scientist and inventor who promoted alternative crops to cotton and methods to prevent soil depletion. He was one of the most prominent black scientists of the ea ...

is often credited because of his scientific work with peanuts and promotion of their use.sweet potatoes

The sweet potato or sweetpotato (''Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant that belongs to the bindweed or morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its large, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a root vegetable. The young sho ...

.

Meat substitutes

Kellogg credited his interest in meat substitutes to Charles William Dabney, an agricultural chemist and the Assistant Secretary of Agriculture. Dabney wrote to Kellogg on the subject around 1895.mutton

Lamb, hogget, and mutton, generically sheep meat, are the meat of domestic sheep, ''Ovis aries''. A sheep in its first year is a lamb and its meat is also lamb. The meat from sheep in their second year is hogget. Older sheep meat is mutton. Gen ...

".

Other foods

In addition to developing imitation meat

A meat alternative or meat substitute (also called plant-based meat or fake meat, sometimes pejoratively) is a food product made from vegetarian or vegan ingredients, eaten as a replacement for meat. Meat alternatives typically approximate qua ...

s variously made from nuts, grains, and soy, Kellogg also developed the first acidophilus soy milk

Soy milk (simplified Chinese: 豆浆; traditional Chinese: 豆漿) also known as soya milk or soymilk, is a plant-based drink produced by soaking and grinding soybeans, boiling the mixture, and filtering out remaining particulates. It is a sta ...

,Dionne quintuplets

The Dionne quintuplets (; born May 28, 1934) are the first quintuplets known to have survived their infancy. The identical girls were born just outside Callander, Ontario, near the village of Corbeil. All five survived to adulthood.

The Dionn ...

. When he learned that Marie had a bowel infection, Kellogg sent a case of his soy acidophilus to their doctor, Allan Roy Dafoe

Dr.Allan Roy Dafoe, OBE (29 May 1883 – 2 June 1943) was a Canadian obstetrician, best known for delivering and caring for the Dionne quintuplets, the first quintuplets known to survive early infancy., page 373.

Biography

Dafoe was born in Mad ...

. When Marie's infection cleared up, Dafoe requested that Kellogg send an ongoing supply for the quintuplets. By 1937, each one consumed at least a pint per day. Another famous patient who benefited from soy acidophilus was polar explorer Richard E. Byrd

Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (October 25, 1888 – March 11, 1957) was an American naval officer and explorer. He was a recipient of the Medal of Honor, the highest honor for valor given by the United States, and was a pioneering American aviator, p ...

.

Medical patents

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Medical inventions

Although they are less discussed than his food creations, Kellogg designed and improved upon a number of medical devices that were regularly used at the Battle Creek Sanitarium in surgical operations and in treatment modalities falling under the term "physiotherapy

Physical therapy (PT), also known as physiotherapy, is one of the allied health professions. It is provided by physical therapists who promote, maintain, or restore health through physical examination, diagnosis, management, prognosis, patient ...

".

Many of the machines invented by Kellogg were manufactured by the Battle Creek Sanitarium Equipment Company, which was established in 1890.electrotherapy

Electrotherapy is the use of electrical energy as a medical treatment. In medicine, the term ''electrotherapy'' can apply to a variety of treatments, including the use of electrical devices such as deep brain stimulators for neurological dise ...

, hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy, formerly called hydropathy and also called water cure, is a branch of alternative medicine (particularly naturopathy), occupational therapy, and physiotherapy, that involves the use of water for pain relief and treatment. The term ...

, and motor therapy, in his work ''The Home Handbook of Domestic Hygiene and Rational Medicine'', first published in 1881.gastrointestinal

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and ...

surgeries, he developed various instruments for these operations. These included specialized hooks and retractors, a heated operating table, and an aseptic drainage tube used in abdominal surgery.light therapy

Light therapy, also called phototherapy or bright light therapy is intentional daily exposure to direct sunlight or similar-intensity artificial light in order to treat medical disorders, especially seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and circadi ...

, mechanical exercising, proper breathing, and hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy, formerly called hydropathy and also called water cure, is a branch of alternative medicine (particularly naturopathy), occupational therapy, and physiotherapy, that involves the use of water for pain relief and treatment. The term ...

. His medical inventions spanned a wide range of applications and included a hot air bath, vibrating chair, oscillomanipulator, window tent for fresh air, pneumograph to graphically represent respiratory habits,loofah

''Luffa'' is a genus of tropical and subtropical vines in the cucumber family (Cucurbitaceae).

In everyday non-technical usage, the luffa, also spelled loofah, usually refers to the fruits of the species ''Luffa aegyptiaca'' and '' Luffa acutan ...

mitt, and an apparatus for home sterilization of milk.RMS Titanic

RMS ''Titanic'' was a British passenger liner, operated by the White Star Line, which sank in the North Atlantic Ocean on 15 April 1912 after striking an iceberg during her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, United ...

''.

Phototherapeutic inventions

Partly motivated by the overcast skies of Michigan winters, Kellogg experimented with and worked to develop light therapies, as he believed in the value of the electric light bulb

An electric light, lamp, or light bulb is an electrical component that produces light. It is the most common form of artificial lighting. Lamps usually have a base made of ceramic, metal, glass, or plastic, which secures the lamp in the soc ...

to provide heat penetration for treating bodily disorders.World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordi ...

in Chicago in 1893.Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

to New York "as a therapeutic novelty".

Electrotherapeutic inventions

Though Kellogg stated that "electricity is not capable of accomplishing half the marvels that are claimed for it by many enthusiastic electrotherapists," he still believed electric currents to be "an extremely valuable therapeutic agent, especially when utilized in connection with hydrotherapy, thermotherapy, and other physiologic methods."[ Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org)] As a result, electrotherapy coils were used in the Static Electrical Department of the Battle Creek Sanitarium especially for cases of paresthesias of neurasthenia, insomnia, and certain forms of neuralgia.

Mechanical massage devices

Massage devices included two- or four-person foot vibrators, a mechanical slapping massage device, and a kneading apparatus that was advertised in 1909 to sell for . Kellogg advocated mechanical massage, a branch of mechanotherapy Mechanotherapy is a type of medical therapeutics in which treatment is given by manual or mechanical means. It was defined in 1890 as “the employment of mechanical means for the cure of disease”. Mechanotherapy employs mechanotransduction in or ...

, for cases of anemia

Anemia or anaemia (British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, or a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin. When anemia comes on slowly, th ...

, general debility, and muscular or nervous weakness.

Irrigator

In 1936, Kellogg filed a petition for his invention of improvements to an "irrigating apparatus particularly adaptable for colonic irrigating, but susceptible of use for other irrigation treatments."

Views on health

Biologic living

Synthesizing his Adventist beliefs with his scientific and medical knowledge, Kellogg created his idea of "biologic living".

Views on tobacco

Kellogg was a prominent member of the anti-tobacco consumption campaign, speaking out often on the issue. He believed that consumption of tobacco not only caused physiological damage, but also pathological, nutritional, moral, and economic devastation onto society. His belief was that "tobacco has not a single redeeming feature… and is one of the most deadly of all the many poisonous plants known to the botanist."

Views on alcohol and other beverages

Though alcoholic beverages were commonly used as a stimulant by the medical community during the time that Kellogg began his medical practice, he was firm in his opposition to the practice.caffeine

Caffeine is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant of the methylxanthine class. It is mainly used recreationally as a cognitive enhancer, increasing alertness and attentional performance. Caffeine acts by blocking binding of adenosine t ...

content of those beverages. His view was that caffeine was a poison. Not only did he detail numerous physiological and developmental problems caused by caffeine, but he also suggested that caffeine usage could lead to moral deficiencies. He blamed the prevalence of these beverages not only on the prohibition of alcoholic beverages at the time, but also on the extensive marketing efforts organized by the producers of these products. Kellogg's view was that "nature has supplied us with pure water, with a great variety of fruit juices and wholesome and harmless flavors quite sufficient to meet all our needs."

As early as the 1880s, Kellogg had prepared charts and lectures on the dangers of tobacco and alcohol, which were used widely by lecturers who encouraged temperance in their students.

Hydropathy

Properties of water

Kellogg has labeled the various uses of hydropathy as being byproducts of the many properties of water. In his 1876 book, ''The Uses of Water in Health & Disease'', he acknowledges both the chemical composition and physical properties of water. Hydrogen and oxygen, when separate, are two "colorless, transparent, and tasteless" gases, which are explosive when mixed. More importantly, water, he says, has the highest specific heat of any compound (although in actuality it does not). As such, the amount of heat and energy needed to elevate the temperature of water is significantly higher than that of other compounds like mercury. Kellogg addressed water's ability to absorb massive amounts of energies when shifting phases. He also highlighted water's most useful property, its ability to dissolve many other substances.

Remedial properties of water

According to Kellogg, water provides remedial properties partly because of vital resistance and partly because of its physical properties. For Kellogg, the medical uses of water begin with its function as a refrigerant, a way to lower body heat by way of dissipating its production as well as by conduction. "There is not a drug in the whole materia medica that will diminish the temperature of the body so readily and so efficiently as water." Water can also serve as a sedative. While other substances serve as sedatives by exerting their poisonous influences on the heart and nerves, water is a gentler and more efficient sedative without any of the negative side-effects seen in these other substances. Kellogg states that a cold bath can often reduce one's pulse by 20 to 40 beats per minute quickly, in a matter of a few minutes. Additionally, water can function as a tonic, increasing both the speed of circulation and the overall temperature of the body. A hot bath accelerates one's pulse from 70 to 150 beats per minute in 15 minutes. Water is also useful as an anodyne since it can lower nervous sensibility and reduce pain when applied in the form of hot fomentation. Kellogg argues that this procedure will often give one relief where every other drug has failed to do so. He also believed that no other treatment could function as well as an antispasmodic, reducing infantile convulsions and cramps, as water. Water can be an effective astringent as, when applied cold, it can arrest hemorrhages. Moreover, it can be very effective in producing bowel movements. Whereas purgatives would introduce "violent and unpleasant symptoms", water would not. Although it would not have much competition as an emetic at the time, Kellogg believed that no other substance could induce vomiting as well as water did. Returning to one of Kellogg's most admired qualities of water, it can function as a "most perfect eliminative". Water can dissolve waste and foreign matter from the blood. These many uses of water led Kellogg to belief that "the aim of the faithful physician should be to accomplish for his patient the greatest amount of good at the least expence of vitality; and it is an indisputable fact that in a large number of cases water is just the agent with which this desirable end can be obtained."

Incorrect uses of the water cure

Although Kellogg praised hydropathy for its many uses, he did acknowledge its limits. "In nearly all cases, sunlight, pure air, rest, exercise, proper food, and other hygienic agencies are quite as important as water. Electricity, too, is a remedy which should not be ignored; and skillful surgery is absolutely indispensable in not a small number of cases." With this belief, he went on to criticize many medical figures who misused or overestimated hydropathy in the treating of disease. Among these, he criticized what he referred to as "Cold-Water Doctors" who would recommend the same remedy regardless of the type of ailment or temperament of the patient. These doctors would prescribe ice-cold baths in unwarmed rooms even during the harshest winters. In his opinion, this prejudicial approach to illness resulted in converting hydropathy to a more heroic type of treatment where many became obsessed with taking baths in ice-cold water. He addresses the negative consequences that resulted from this "infatuation", among them tuberculosis and other diseases. This dangerous habit was only exacerbated by physicians who used hydropathy in excess. Kellogg recounts an instance where a patient with a low typhus fever was treated with 35 cold packs while in a feeble state and, not to the surprise of Kellogg, died. Kellogg posits this excessive and dangerous use of hydropathy as a return to the "violent processes" of bloodletting, antimony, mercury and purgatives. Kellogg also criticizes the ignorance in "Hydropathic Quacks" as well as in Preissnitz, the founder of modern hydropathy, himself. Kellogg states that the "Quacks" as well as Preissnitz are ignorant for overestimating the hydropathy as a "cure-all" remedy without understanding the true nature of disease.

Views on sexuality

Both as a doctor and an Adventist, Kellogg was an advocate of sexual abstinence. As a physician, Kellogg was well aware of the damaging impact of sexually transmissible diseases such as syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

, which was incurable before the 1910s.Seventh-day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbath, and ...

.

Kellogg was an adherent of the teachings of Ellen G. White

Ellen Gould White (née Harmon; November 26, 1827 – July 16, 1915) was an American woman author and co-founder of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Along with other Adventist leaders such as Joseph Bates and her husband James White, she wa ...

and Sylvester Graham. Graham, who inspired the creation of the graham cracker

A graham cracker (pronounced or in America) is a sweet flavored cracker made with graham flour that originated in the United States in the mid-19th century, with commercial development from about 1880. It is eaten as a snack food, usually ho ...

, advocated keeping the diet plain to prevent sexual arousal.

Kellogg's work on diet was influenced by the belief that a plain and healthy diet, with only two meals a day, would reduce sexual feelings.

Those experiencing temptation were to avoid stimulating food and drinks, and eat very little meat, if any.

Kellogg set out his views on such matters in one of his larger books, published in increasingly longer editions around the start of the 20th century. He was unmarried when he published the first edition of ''Plain Facts about Sexual Life'' (1877, 1st, 356 pages). He and his bride apparently wrote an additional 156 pages during his honeymoon, releasing the new edition as ''Plain Facts for Old and Young'' (1879, 2nd, 512 pages). By 1886 it was 644 pages; by 1901, 720 pages; by 1903, 798; and in 1917 Kellogg published a four-volume edition of 900 pages. An estimated half-million copies were sold, many by discreet door-to-door canvassers.

"Warfare with passion"

Kellogg warned that many types of sexual activity, including "excesses" that couples could be guilty of within marriage, were against nature, and therefore, extremely unhealthy. He drew on the warnings of William ActonAnthony Comstock

Anthony Comstock (March 7, 1844 – September 21, 1915) was an anti-vice activist, United States Postal Inspector, and secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV), who was dedicated to upholding Christian morality. He o ...

.onanism

Onan ''Aunan'' was a figure detailed in the Book of Genesis chapter 38, as the second son of Judah and Shuah, and the brother of Er and Shelah. After being commanded by Judah to procreate with the late Er's wife Tamar, he instead "spilled his ...

", credited to one Dr. Adam Clarke

Adam Clarke (176226 August 1832) was a British Methodist theologian who served three times as President of the Wesleyan Methodist Conference (1806–07, 1814–15 and 1822–23). A biblical scholar, he published an influential Bible commentary ...

. Kellogg strongly warned against the habit in his own words, claiming of masturbation-related deaths "such a victim literally dies by his own hand", among other condemnations. He felt that masturbation destroyed not only physical and mental health, but moral health as well. Kellogg also believed the practice of this "solitary-vice" caused cancer of the womb, urinary diseases, nocturnal emissions, impotence, epilepsy, insanity, and mental and physical debility; "dimness of vision" was only briefly mentioned. Kellogg thought that masturbation was the worst evil one could commit; he often referred to it as "self-abuse".

Kellogg considered sexual climax to be a serious exhaustion of nervous energy, writing ".. exis accompanied by a peculiar nervous spasm, ...one more exhausting to the system than any other..."

Masturbation prevention

A common myth in popular culture states that Kellogg is responsible for the widespread prevalence of circumcision in the United States. This is not accurate, as Kellogg never promoted routine circumcision of all males in his writings; rather, only men who were chronically addicted to masturbation.Lewis Sayre

Lewis Albert Sayre (February 29, 1820 – September 21, 1900) was a leading American orthopedic surgeon of the 19th century. He performed the first operation to cure hip-joint ankylosis, introduced the method of suspending the patient followed ...

, the founder of the American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) is a professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. Founded in 1847, it is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was approximately 240,000 in 2016.

The AMA's state ...

, have had a much more significant influence on the surgery's popularity within the country.circumcised

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. Topic ...

himself at age 37. His methods for the "rehabilitation" of masturbation addicts included measures up to the point of cutting off part of the genitals, without anesthetic, on both sexes; he wrote men who did should be circumcised and women that did should have carbolic acid

Phenol (also called carbolic acid) is an aromaticity, aromatic organic compound with the molecular chemical formula, formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatility (chemistry), volatile. The molecule consists of a phenyl group () ...

applied to their clitoral glans.nymphomania

Hypersexuality is extremely frequent or suddenly increased libido. It is controversial whether it should be included as a clinical diagnosis used by mental healthcare professionals. Nymphomania and satyriasis were terms previously used for the c ...

, he recommended

Later life

Kellogg would live for over 60 years after writing ''Plain Facts''. He continued to work on healthy eating advice and run the sanitarium, although this was hit by the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

and had to be sold. He ran another institute in Florida, which was popular throughout the rest of his life, although it was a distinct step down from his Battle Creek institute.

''Good Health'' journal

Kellogg became editor of the ''Health Reformer'' journal in 1874. The journal changed its name to ''Good Health'' in 1879 and Kellogg held his editorial position for many years until his death. The ''Good Health'' journal had more than 20,000 subscribers and was published until 1955.

Race Betterment Foundation

Kellogg was outspoken about his views

A view is a sight or prospect or the ability to see or be seen from a particular place.

View, views or Views may also refer to:

Common meanings

* View (Buddhism), a charged interpretation of experience which intensely shapes and affects thou ...

on race

Race, RACE or "The Race" may refer to:

* Race (biology), an informal taxonomic classification within a species, generally within a sub-species

* Race (human categorization), classification of humans into groups based on physical traits, and/or s ...

and his belief in racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

, regardless of the fact that he himself raised several black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

foster children. In 1906, together with Irving Fisher

Irving Fisher (February 27, 1867 – April 29, 1947) was an American economist, statistician, inventor, eugenicist and progressive social campaigner. He was one of the earliest American neoclassical economists, though his later work on debt def ...

and Charles Davenport

Charles Benedict Davenport (June 1, 1866 – February 18, 1944) was a biologist and eugenics, eugenicist influential in the Eugenics in the United States, American eugenics movement.

Early life and education

Davenport was born in Stamford, Co ...

, Kellogg founded the Race Betterment Foundation

The Race Betterment Foundation was a eugenics and racial hygiene organization founded in 1914 at Battle Creek, Michigan by John Harvey Kellogg due to his concerns about what he perceived as "race degeneracy". The foundation supported conferences ...

, which became a major center of the new eugenics movement in America. Kellogg was in favor of racial segregation in the United States

In the United States, racial segregation is the systematic separation of facilities and services such as Housing in the United States, housing, Healthcare in the United States, healthcare, Education in the United States, education, Employment in ...

and he also believed that immigrants and non-whites would damage the white American population's gene pool.

Late relationship with Will Keith Kellogg

Kellogg had a long personal and business split with his brother, after fighting in court for the rights to cereal recipes. The Foundation for Economic Education

The Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) is an American conservative, libertarian economic think tank. Founded in 1948 in New York City, FEE is now headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia. It is a member of the State Policy Network.

FEE offers ...

records that the nonagenarian J.H. Kellogg prepared a letter seeking to reopen the relationship. His secretary decided her employer had demeaned himself in it and refused to send it. The younger Kellogg did not see it until after his brother's death.

In popular culture

British actor Anthony Hopkins

Sir Philip Anthony Hopkins (born 31 December 1937) is a Welsh actor, director, and producer. One of Britain's most recognisable and prolific actors, he is known for his performances on the screen and stage. Hopkins has received many accolad ...

plays a highly fictionalized Dr. J.H. Kellogg in the American 1994 film '' The Road to Wellville'' by Alan Parker. This film depicts the fire of the sanitarium building complex, and ends with Dr. Kellogg, years after, dying of a heart attack while diving from a high board.

Misconceptions

Several popular misconceptions falsely attribute various cultural practices, inventions, and historical events to Kellogg.Kellogg's corn flakes

Corn flakes, or cornflakes, are a breakfast cereal made from toasting flakes of corn (maize). The cereal, originally made with wheat, was created by Will Kellogg in 1894 for patients at the Battle Creek Sanitarium where he worked with his bro ...

were invented or marketed to prevent masturbation. In actuality, they were promoted to prevent indigestion.common misconception

Each entry on this list of common misconceptions is worded as a correction; the misconceptions themselves are implied rather than stated. These entries are concise summaries of the main subject articles, which can be consulted for more detail.

...

falsely credits Kellogg with popularizing routine circumcision in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and broader Anglosphere

The Anglosphere is a group of English-speaking world, English-speaking nations that share historical and cultural ties with England, and which today maintain close political, diplomatic and military co-operation. While the nations included in d ...

.masturbation

Masturbation is the sexual stimulation of one's own genitals for sexual arousal or other sexual pleasure, usually to the point of orgasm. The stimulation may involve hands, fingers, everyday objects, sex toys such as vibrators, or combinatio ...

.Lewis Sayre

Lewis Albert Sayre (February 29, 1820 – September 21, 1900) was a leading American orthopedic surgeon of the 19th century. He performed the first operation to cure hip-joint ankylosis, introduced the method of suspending the patient followed ...

, president of the American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) is a professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. Founded in 1847, it is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was approximately 240,000 in 2016.

The AMA's state ...

, leading to its widespread adoption in the Anglosphere.

See also

* Eugenics in the United States

Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices which aims at improving the genetic quality of the human population, played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States from the late 19th century into the mid-20th century. T ...

* Sylvester Graham

Selected publications

* 1877

* 1888

* 1893 ''Ladies Guide in Health and Disease''

* 1880, 1886, 1899 ''The Home Hand-Book of Domestic Hygiene and Rational Medicine''

* 1903 ''Rational Hydrotherapy''

* 1910 ''Light Therapeutics''

* 1914 ''Needed – A New Human Race'' Official Proceedings: Vol. I, Proceedings of the First National Conference on Race Betterment. Battle Creek, MI: Race Betterment Foundation, 431–450.

* 1915 "Health and Efficiency" Macmillan M. V. O'Shea and J. H. Kellogg (The Health Series of Physiology and Hygiene)

* 1915 ''The Eugenics Registry'' Official Proceedings: Vol II, Proceedings of the Second National Conference on Race Betterment. Battle Creek, MI: Race Betterment Foundation.

* 1918 "The Itinerary of a Breakfast" Funk & Wagnalls Company: New York and London

* 1922 ''Autointoxication or Intestinal Toxemia''

* 1923 ''Tobaccoism or How Tobacco Kills''

* 1927 ''New Dietetics: A Guide to Scientific Feeding in Health and Disease''

* 1929 '' Art of Massage: A Practical Manual for the Nurse, the Student and the Practitioner''

References

Further reading

Kellogg, John Harvey (1903). ''The Living Temple''. Battle Creek, Mich., Good Health Publishing Company. 568 pages.

* Deutsch, Ronald M. ''The Nuts Among the Berries''. New York, Ballantine Books, 1961, 1967

* Schwarz, Richard W. ''John Harvey Kellogg: Pioneering Health Reformer''. Hagerstown, MD: Review and Herald, 2006

* Wilson, Brian C. ''Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and the Religion of Biologic Living''. Indianapolis, IN; Indiana University Press, 2014

*

External links

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20050121094720/http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new?id=KelPlai&tag=public&images=images%2Fmodeng&data=%2Ftexts%2Fenglish%2Fmodeng%2Fparsed&part=0 Etext of ''Plain Facts For Old And Young'']

Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and Battle Creek Foods: Work with Soy

from the Soy foods Center (Chinese characters only)

(Blank page)

Adventist Archives

Contains many articles written by Dr. Kellogg

Concerns his dispute with his church in 1907

*

*

*

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kellogg, John Harvey

1852 births

1943 deaths

American celibacy advocates

American drink industry businesspeople

American eugenicists

American food company founders

American former Protestants

American inventors

American nutritionists

American people of English descent

American temperance activists

American vegetarianism activists

Anti-smoking activists

Diet food advocates

Eastern Michigan University alumni

Gastroenterology

Light therapy advocates

New York University Grossman School of Medicine alumni

Opposition to masturbation

People disfellowshipped by the Seventh-day Adventist Church

People from Battle Creek, Michigan

Seventh-day Adventists from Michigan

Seventh-day Adventists in health science

Tea critics

John Harvey Kellogg was born in Tyrone, Michigan, on February 26, 1852, to John Preston Kellogg (1806–1881) and his second wife Ann Janette Stanley (1824–1893). His father, John Preston Kellogg, was born in Hadley, Massachusetts; his ancestry can be traced back to the founding of Hadley, Massachusetts, where a great-grandfather operated a ferry.

John Preston Kellogg and his family moved to Michigan in 1834, and after his first wife's death and his remarriage in 1842, to a farm in Tyrone Township.

In addition to six children from his first marriage, John Preston Kellogg had 11 children with his second wife Ann, including John Harvey and his younger brother,

John Harvey Kellogg was born in Tyrone, Michigan, on February 26, 1852, to John Preston Kellogg (1806–1881) and his second wife Ann Janette Stanley (1824–1893). His father, John Preston Kellogg, was born in Hadley, Massachusetts; his ancestry can be traced back to the founding of Hadley, Massachusetts, where a great-grandfather operated a ferry.

John Preston Kellogg and his family moved to Michigan in 1834, and after his first wife's death and his remarriage in 1842, to a farm in Tyrone Township.

In addition to six children from his first marriage, John Preston Kellogg had 11 children with his second wife Ann, including John Harvey and his younger brother,  Kellogg hoped to become a teacher, and at age 16 taught a district school in Hastings, Michigan. By age 20, he had enrolled in a teacher's training course offered by

Kellogg hoped to become a teacher, and at age 16 taught a district school in Hastings, Michigan. By age 20, he had enrolled in a teacher's training course offered by  Sanitarium visitors also engaged in breathing exercises and mealtime marches, to promote proper

Sanitarium visitors also engaged in breathing exercises and mealtime marches, to promote proper  Around 1877, John H. Kellogg began experimenting to produce a softer breakfast food, something easy to chew. He developed a dough that was a mixture of wheat,

Around 1877, John H. Kellogg began experimenting to produce a softer breakfast food, something easy to chew. He developed a dough that was a mixture of wheat,  *

*

*

*

*

*

*

*