John Harrison Clark on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Harrison Clark or Changa-Changa (c. 1860–1927) effectively ruled much of what is today southern Zambia from the early 1890s to 1902. He arrived alone from South Africa in about 1887, reputedly as an

John Harrison Clark or Changa-Changa (c. 1860–1927) effectively ruled much of what is today southern Zambia from the early 1890s to 1902. He arrived alone from South Africa in about 1887, reputedly as an

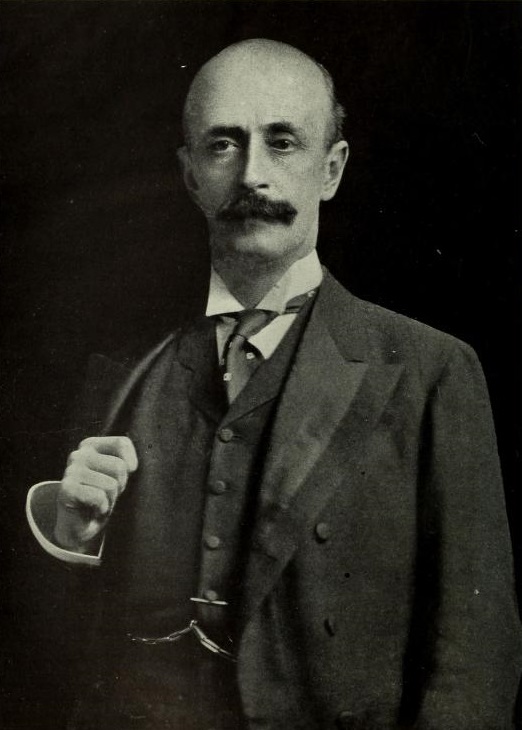

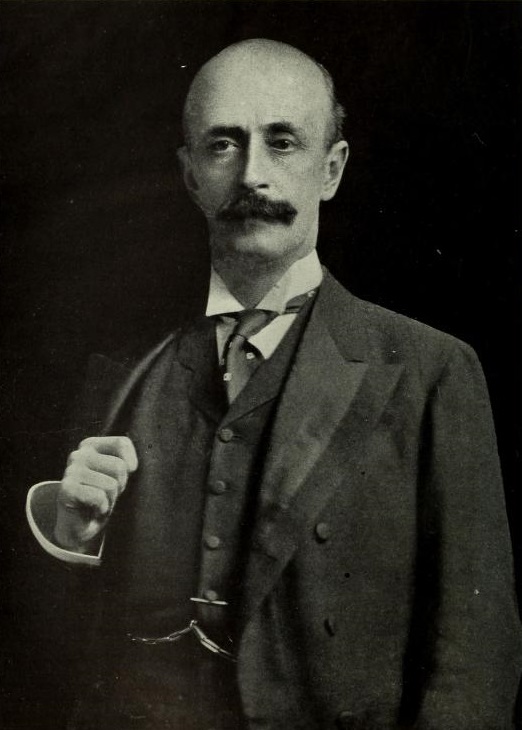

Not much is known about John Harrison Clark's early life. The son of a man "in the hardware business" (according to a military officer who knew him, Major G R Deare), he was born in

Not much is known about John Harrison Clark's early life. The son of a man "in the hardware business" (according to a military officer who knew him, Major G R Deare), he was born in

The

The

Chintanda's affidavit caused the BSAC to become concerned about Clark's continued authority in North-Eastern Rhodesia and to begin investigating him more thoroughly. The situation was complicated when, after a month's perusal, the company's lawyers resolved that the courts in Salisbury and Bulawayo held no jurisdiction outside Southern Rhodesia and therefore could not hear any case brought against Clark. On 4 July 1899,

Chintanda's affidavit caused the BSAC to become concerned about Clark's continued authority in North-Eastern Rhodesia and to begin investigating him more thoroughly. The situation was complicated when, after a month's perusal, the company's lawyers resolved that the courts in Salisbury and Bulawayo held no jurisdiction outside Southern Rhodesia and therefore could not hear any case brought against Clark. On 4 July 1899,

Clark became a successful farmer, experimenting with the growing of rubber, cotton and other plants previously absent from the area. His cotton plantation developed promisingly for a few years, but he abandoned it after heavy rain destroyed an entire crop around 1909. He remained on the farm until the late 1910s, when he either gave or sold it to Catholic missionaries, and moved to

Clark became a successful farmer, experimenting with the growing of rubber, cotton and other plants previously absent from the area. His cotton plantation developed promisingly for a few years, but he abandoned it after heavy rain destroyed an entire crop around 1909. He remained on the farm until the late 1910s, when he either gave or sold it to Catholic missionaries, and moved to

John Harrison Clark or Changa-Changa (c. 1860–1927) effectively ruled much of what is today southern Zambia from the early 1890s to 1902. He arrived alone from South Africa in about 1887, reputedly as an

John Harrison Clark or Changa-Changa (c. 1860–1927) effectively ruled much of what is today southern Zambia from the early 1890s to 1902. He arrived alone from South Africa in about 1887, reputedly as an outlaw

An outlaw, in its original and legal meaning, is a person declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, all legal protection was withdrawn from the criminal, so that anyone was legally empowered to persecute or kill them ...

, and assembled and trained a private army of Senga natives that he used to drive off various bands of slave-raiders. He took control of a swathe of territory on the north bank of the Zambezi

The Zambezi River (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than hal ...

river called Mashukulumbwe, became known as Chief "Changa-Changa" and, through a series of treaties with local chiefs, gained mineral and labour concessions covering much of the region.

Starting in 1897, Clark attempted to secure protection for his holdings from the British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expecte ...

. The Company took little notice of him. A local chief, Chintanda, complained to the Company in 1899 that Clark had secured his concessions while passing himself off as a Company official and had been collecting hut tax

The hut tax was a form of taxation introduced by British in their African possessions on a "per hut" (or other forms of household) basis. It was variously payable in money, labour, grain or stock and benefited the colonial authorities in four inter ...

for at least two years under this pretence. The Company resolved to remove him from power, and did so in 1902. Clark then farmed for about two decades, with some success, and moved in the late 1910s to Broken Hill

Broken Hill is an inland mining city in the far west of outback New South Wales, Australia. It is near the border with South Australia on the crossing of the Barrier Highway (A32) and the Silver City Highway (B79), in the Barrier Range. It is ...

. There he became a prominent local figure, and a partner in the first licensed brewery

A brewery or brewing company is a business that makes and sells beer. The place at which beer is commercially made is either called a brewery or a beerhouse, where distinct sets of brewing equipment are called plant. The commercial brewing of be ...

in Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in southern Africa, south central Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by Amalgamation (politics), amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-West ...

. Remaining in Broken Hill for the rest of his life, he died there in 1927.

Early life

Not much is known about John Harrison Clark's early life. The son of a man "in the hardware business" (according to a military officer who knew him, Major G R Deare), he was born in

Not much is known about John Harrison Clark's early life. The son of a man "in the hardware business" (according to a military officer who knew him, Major G R Deare), he was born in Port Elizabeth

Gqeberha (), formerly Port Elizabeth and colloquially often referred to as P.E., is a major seaport and the most populous city in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is the seat of the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality, Sou ...

, Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

around 1860, and engaged for a time in the Cape Mounted Riflemen

The Cape Mounted Riflemen were South African military units.

There were two separate successive regiments of that name. To distinguish them, some military historians describe the first as the "imperial" Cape Mounted Riflemen (originally the ' ...

during the 1880s. A tall, physically strong man, he wore a large black moustache and was regarded as a fine shot and a capable hunter.

Harrison Clark left South Africa in 1887, but it is unclear why; according to a story that may be apocryphal, he fled the country as an outlaw

An outlaw, in its original and legal meaning, is a person declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, all legal protection was withdrawn from the criminal, so that anyone was legally empowered to persecute or kill them ...

soon after his revolver fired—by accident, so the story goes—and killed a man. Whatever the truth, he travelled to Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

, then a Portuguese territory, where he made his way upriver along the Zambezi

The Zambezi River (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than hal ...

until he reached Feira, a long-abandoned Portuguese settlement at the confluence of the Zambezi and Luangwa River

The Luangwa River is one of the major tributaries of the Zambezi River, and one of the four biggest rivers of Zambia. The river generally floods in the rainy season (December to March) and then falls considerably in the dry season. It is one of ...

s, in what is today southern Zambia. Feira was founded by missionaries from Portugal in about 1720, but by 1887 it was a ghost town

Ghost Town(s) or Ghosttown may refer to:

* Ghost town, a town that has been abandoned

Film and television

* Ghost Town (1936 film), ''Ghost Town'' (1936 film), an American Western film by Harry L. Fraser

* Ghost Town (1956 film), ''Ghost Town'' ...

. Its last inhabitants had fled amid a native rising about half a century before, and since then it had been deserted.

David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, an explorer in Africa, and one of the most popular British heroes of t ...

, who visited Feira in 1856, described it as utterly ruined at that time, but still conspicuous by the ramshackle monastery buildings on the site. When Clark arrived about three decades later, the Portuguese still maintained a '' boma'' (fort) called Zumbo

Zumbo is the westernmost town in Mozambique, on the Zambezi River. Lying on the north-east bank of the Zambezi- Luangwa River confluence, it is a border town, with Zambia (and the town of Luangwa, previously called Feira) across the Luangwa Riv ...

on the opposite bank of the Luangwa, but the surrounding country, then called Mashukulumbwe, was largely wild, and out of the control of any government. Harrison Clark settled at Feira, initially alone. According to a letter he wrote in 1897, he flew the British Merchant Navy's Red Ensign flag over his house.Letter from Clark to Earl Grey (October 1897), included in

Rise to power

Slave-raiding was rife in Mashukulumbwe, with gangs of Arab, Portuguese and mixedChikunda Chikunda, sometimes rendered as Achicunda, was the name given from the 18th century onwards to the slave-warriors of the Afro-Portuguese estates known as Prazos in Zambezia, Mozambique. They were used to defend the prazos and police their inhabitan ...

-Portuguese ethnicity competing for the capture of local Baila and Batonga people for use as slaves. Clark, who became known to the locals as "Changa-Changa", raised and trained an "army" from among the Senga people, and issued these men a vague uniform. How he became a chief is equivocal—Deare asserted that Clark arrived in Mashukulumbwe "on the very day the chief died ... ndwas finally made chief of the tribe". According to a story told by an acquaintance, Harry Rangeley, and partly corroborated by Alexander Scott in the ''Central African Post'' in 1949, he became chief by virtue of winning a battle. Rangeley's version has him defeating a rival chief; Scott has Clark coming to the rescue of a Baila village under attack by Portuguese slavers, "liberat ngthe slaves" and thereupon being proclaimed chief by the grateful villagers.

As chief, Clark secured his authority with his army of Senga warriors, defined and collected "taxes" and oversaw the activities of foreign traders in the area. Locals paid tribute in the form of cattle, and overseas merchants had to obtain a "trading licence" from Harrison Clark before they could operate in his territory. Where a trader was harvesting ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals is ...

to sell overseas, Clark levied every other tusk as an "export tax". As well as regulating local trade, Clark encouraged the people to make paths between their villages, and repeatedly defended them against the various slave-raiding gangs. As his Senga troops expanded, he conferred various grandiose titles on himself, including "King of the Senga" and "Chief of the Mashukulumbwe".

All of this caused considerable annoyance to the Portuguese at Zumbo, though the ''boma'' coexisted with Clark's settlement for the most part. The most prominent trans-river clash came when Clark demonstrated the strength of his army by overpowering the fort's garrison, pulling down the Portuguese flag and running up the Union Jack

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

in its place. He then returned to Feira, leaving the British flag flying over Zumbo. His point made, he made no attempt to stop the Portuguese garrison from returning.; The Portuguese arrested Clark at one point, according to one story, but released him after the native troopers refused to guard him, saying he was "too great a man to be arrested". A similar tale has Harrison Clark being captured in Mozambique and deported to Feira under guard by two Portuguese soldiers; these men found the journey so harrowing that Clark ended up escorting them back. According to one of Clark's indigenous followers, he once put an intruding Chikunda force to flight simply by bellowing at the enemy leader to " voetsek you bloody nigger".

Clark consolidated his chieftainship by marrying a daughter of Mpuka, the chief of the Chikunda people; according to Deare this was just one of "the usual assortment of wives". In 1895 he relocated north to the confluence of the Lukasashi and Lunsemfwa River

The Lunsemfwa River is a tributary of the Luangwa Rivers in Zambia and part of the Zambezi River basin. It is a popular river for fishing, containing large populations of tigerfish and bream.

It rises on the south-central African plateau at an ele ...

s, where he established his own village. He named the settlement "Algoa" after the Portuguese name for Port Elizabeth, and lived in a small stone fort he built. Writing in 1954, the historian W V Brelsford described Clark's sphere of influence from Algoa as "the Luano Valley and the uplands as far westwards as the Kafue

Kafue is a town in the Lusaka Province of Zambia and it lies on the north bank of the Kafue River, after which it is named. It is the southern gateway to the central Zambian plateau on which Lusaka and the mining towns of Kabwe and the Copperbe ...

and southwards to Feira".

Contact with the British South Africa Company

The

The British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expecte ...

(BSAC), established by Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Br ...

in 1889, was designed to occupy and develop the area immediately north of the Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

, with the ultimate goal of aiding Rhodes's dream of a Cape to Cairo railway

The Cape to Cairo Railway was an unfinished project to create a railway line crossing Africa from south to north. It would have been the largest and most important railway of that continent. It was planned as a link between Cape Town in Sout ...

through British territory. Having a firm hold over Matabeleland

Matabeleland is a region located in southwestern Zimbabwe that is divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Bulawayo, and Matabeleland South. These provinces are in the west and south-west of Zimbabwe, between the Limpopo and Zambezi r ...

, Mashonaland

Mashonaland is a region in northern Zimbabwe.

Currently, Mashonaland is divided into four provinces,

* Mashonaland West

* Mashonaland Central

* Mashonaland East

* Harare

The Zimbabwean capital of Harare, a province unto itself, lies entirely ...

and Barotseland

Barotseland ( Lozi: Mubuso Bulozi) is a region between Namibia, Angola, Botswana, Zimbabwe including half of eastern and northern provinces of Zambia and the whole of Democratic Republic of Congo's Katanga Province. It is the homeland of the ...

by 1894, the company began officially calling its domain "Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of S ...

" in 1895. The BSAC sought to further expand its influence north of the Zambezi, and to that end regularly sent expeditions into what was dubbed North-Eastern Rhodesia

North-Eastern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in south central Africa formed in 1900.North-Eastern Rhodesia Order in Council, 1900 The protectorate was administered under charter by the British South Africa Company. It was one of what were ...

to negotiate concessions with local rulers and found settlements.

In 1896, Major Deare led one such expedition north from the main seat of Company administration, Fort Salisbury, to meet with the Ngoni chief Mpezeni Mpezeni (also spelt ''Mpeseni'') (1830–1900) was warrior-king of one of the largest Ngoni groups of central Africa, based in what is now the Chipata District of Zambia, at a time when the British South Africa Company (BSAC) of Cecil Rhodes was ...

, who ruled to the east of Harrison Clark. One day, to Deare's surprise, a small group of warriors approached his party from the west, carrying a letter. This message, written in English and signed "Changa-Changa, Chief of the Mashukulumbwe"—the name John Harrison Clark was given in the body of the letter—said that its author had heard of a white man being entertained recently by Mpezeni, and wished to provide the same hospitality at Algoa. "Really, wonders never cease!" Deare recalled. "I had heard of this man on the Zambezi and had known him well many years ago in the Cape Colony ... We had both lived in the same town for years. I learnt his story later." It is unclear whether Deare took up Clark's invitation to Algoa.

Harrison Clark subsequently sought protection from the British South Africa Company. He negotiated concessions with two neighbouring chiefs, Chintanda and Chapugira, each of whom signed over the mining and labour rights for his respective territory in return for a specified fee whenever Clark wished to use them. In August 1897, Clark wrote to the Company administrator in Salisbury, Earl Grey

Earl Grey is a title in the peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1806 for General Charles Grey, 1st Baron Grey. In 1801, he was given the title Baron Grey of Howick in the County of Northumberland, and in 1806 he was created Viscou ...

, requesting that the Company honour these holdings, enclosing copies of the concessions he had secured. Also providing a cursory description of gold mining prospects in the region, Clark criticised the actions of Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Warton, who was in the vicinity representing the North Charterland Exploration Company, a BSAC subsidiary. "Mashukulumbwe can be occupied without fighting," he wrote. "I am on friendly terms with all the natives, and, if necessary, can raise a force of three to seven thousand to operate on Mfisini pezenior Mashukulumbwe. Colonel Warton's Administration of this country has been a mistake; the country is rich in alluvial

Alluvium (from Latin ''alluvius'', from ''alluere'' 'to wash against') is loose clay, silt, sand, or gravel that has been deposited by running water in a stream bed, on a floodplain, in an alluvial fan or beach, or in similar settings. Alluv ...

and reef gold."Letter from Clark to Earl Grey (August 1897), included in The Company took little notice of Clark, but he continued in the same vein, acquiring similar concessions from the chiefs Chetentaunga, Luvimbie, Sinkermeronga and Mubruma over the following two years.

Clark wrote to the Company again on 12 April 1899, once more attaching copies of his concessions, with an offer to supply the BSAC settlements in Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally kn ...

with contract labourers taken from among his neighbouring chiefs' populations. He said he had permission from all of the chiefs involved to do so. He requested as his fee £1 per man, and said that he had agreed a monthly wage of 10 shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence o ...

s for each worker plus food, accommodation and fuel. Having split his concessions into two sections to draw labour from, Clark proposed to provide Salisbury with workers from his eastern concessions, and Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; Ndebele: ''Bulawayo'') is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council cl ...

with those from the west. The chiefs had agreed to provide workers on contracts lasting six months, but Clark wrote that he could attempt to supply labour all year round if the Company wished.Letter from Clark to Milton (April 1899), included in

Decline and fall

On 14 April 1899, Chief Chintanda gave a BSAC commissioner at Mazoe, Southern Rhodesia a statement in which, among other things, he asserted that Clark had been claiming to be a Company official and had been collecting tariffs such ashut tax

The hut tax was a form of taxation introduced by British in their African possessions on a "per hut" (or other forms of household) basis. It was variously payable in money, labour, grain or stock and benefited the colonial authorities in four inter ...

under that pretence for at least two years. Clark's labour and mining concessions, Chintanda said, had been agreed under the impression that he represented the BSAC. Chintanda furthermore claimed that Clark was a prolific womaniser who had once raped a pregnant woman. "Whenever Clark sees a girl he fancies he takes her as his mistress for a few days, and when tired of her sends her home," Chintanda said. "The fathers and husbands of these girls are constantly complaining to me about Clark's actions, but I can do nothing as Clark is a white man, and professed to be representing the government." The chief asked the company to send a genuine representative.Statement from Catino Francisco Lubino Chintanda (April 1899), included in

Chintanda's affidavit caused the BSAC to become concerned about Clark's continued authority in North-Eastern Rhodesia and to begin investigating him more thoroughly. The situation was complicated when, after a month's perusal, the company's lawyers resolved that the courts in Salisbury and Bulawayo held no jurisdiction outside Southern Rhodesia and therefore could not hear any case brought against Clark. On 4 July 1899,

Chintanda's affidavit caused the BSAC to become concerned about Clark's continued authority in North-Eastern Rhodesia and to begin investigating him more thoroughly. The situation was complicated when, after a month's perusal, the company's lawyers resolved that the courts in Salisbury and Bulawayo held no jurisdiction outside Southern Rhodesia and therefore could not hear any case brought against Clark. On 4 July 1899, Arthur Lawley

Arthur Lawley, 6th Baron Wenlock, (12 November 1860 – 14 June 1932) was a British colonial administrator who served variously as Administrator of Matabeleland, Governor of Western Australia, Lieutenant-Governor of the Transvaal, and Governo ...

, the company's administrator in Matabeleland, wrote to Cape Town to report the situation to the resident High Commissioner for Southern Africa

The British office of high commissioner for Southern Africa was responsible for governing British possessions in Southern Africa, latterly the protectorates of Basutoland (now Lesotho), the Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana) and Swaziland ...

, Alfred Milner

Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, (23 March 1854 – 13 May 1925) was a British statesman and colonial administrator who played a role in the formulation of British foreign and domestic policy between the mid-1890s and early 1920s. From De ...

. Lawley briefly summarised the charges against Clark and requested permission to hold a court north of the Zambezi under the supervision of one of three chiefs friendly to the company. Milner replied on 17 August that he could not legally sanction this, and that Lawley should pursue the matter further only when authority extended over Clark's area.

On 24 August 1899, Sub-Inspector A M Harte-Barry of the British South Africa Police

The British South Africa Police (BSAP) was, for most of its existence, the police force of Rhodesia (renamed Zimbabwe in 1980). It was formed as a paramilitary force of mounted infantrymen in 1889 by Cecil Rhodes' British South Africa Company, from ...

interviewed Chief Mubruma, who corroborated much of what Chintanda had said regarding Clark's claims to represent the company. Mubruma said that Clark had visited the previous week and had told him to have his men ready for work south of the river within a month. When told that Clark had no connection with the BSAC, Mubruma said that he would not give Clark the workers, but would readily take part in the kind of scheme he had suggested if the Company wished. He made no comment relevant to Clark's alleged sexual misconduct.Letter from Harte-Barry (August 1899), included in

The BSAC established two forts to the north-west of Algoa in 1900, then a ''boma'' at Feira in 1902, bringing Mashukulumbwe under Company control. Harrison Clark said that his concessions gave him authority over the area and demanded that the Company pay him for them. The BSAC said Clark's documents were illegal and refused to deal with him. It offered him compensation, the form of which differs by source; Brelsford and a man who knew Clark personally during the 1920s, Colonel N O Earl Spurr, say that he was given farms as compensation, while a 1920s business acquaintance, A M Bentley, writes that the Company promised grants of land and the right to reserve some mining claims. Clark reluctantly accepted the compensation when he realised that to challenge the BSAC he would have to travel a great distance, possibly to England, and invest heavily in a court case he would probably lose.

Later life and death

Broken Hill

Broken Hill is an inland mining city in the far west of outback New South Wales, Australia. It is near the border with South Australia on the crossing of the Barrier Highway (A32) and the Silver City Highway (B79), in the Barrier Range. It is ...

, one of the largest settlements in what had become Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in southern Africa, south central Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by Amalgamation (politics), amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-West ...

in 1911. Here he lived for the rest of his life. Retaining "Changa-Changa" as a nickname, he helped to develop various businesses and events, acted as a partner in the first licensed brewery

A brewery or brewing company is a business that makes and sells beer. The place at which beer is commercially made is either called a brewery or a beerhouse, where distinct sets of brewing equipment are called plant. The commercial brewing of be ...

in Northern Rhodesia (alongside Lester Blake-Jolly), and became "one of the pillars of society in the Broken Hill of those days", according to Spurr. He owned one of the first automobiles in Northern Rhodesia—a dark green Ford Model T

The Ford Model T is an automobile that was produced by Ford Motor Company from October 1, 1908, to May 26, 1927. It is generally regarded as the first affordable automobile, which made car travel available to middle-class Americans. The relati ...

.

According to Brelsford, the elderly Harrison Clark remained highly respected among the indigenous people and was sometimes called upon to settle disputes. His last job was personnel manager at a local mine. He dedicated his final years to the writing of a book about his life, the manuscript for which was lost when his house burned down. Clark alleged that the BSAC orchestrated the fire to stop him from publishing unflattering information about the early days of Company rule. He died from heart disease in Broken Hill on 9 December 1927, aged about 67, and was buried in the Protestant section of the town cemetery. The modest savings he possessed at the time of his death were left to his sister in Port Elizabeth.

According to M D D Newitt, Clark embodied much of the pioneering spirit of the time and was "an object of legend" to his fellow frontiersmen. "He had led a wild, tough life but it had not turned him either into a rascal or into an uncouth bush dweller," Brelsford writes. "Changa-Changa" endured in the local vernacular as a word roughly meaning "boss", and was still in use in Zambia in the 1970s. Summarising Clark's life, Peter Duignan and Lewis Gann conclude that he "experienced in his own person the transition from bush feudalism to capitalism."

References

;Journal articles * * * ;Bibliography * * * * * *Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Clark, John Harrison Northern Rhodesia people South African explorers Settlers of Zambia Traditional rulers in Zambia 1860 births 1927 deaths Explorers of Africa Micronational leaders People from Port Elizabeth South African military personnel South African people of English descent White South African people 19th-century explorers 19th-century British politicians 20th-century British politicians