John Griffith Chaney on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

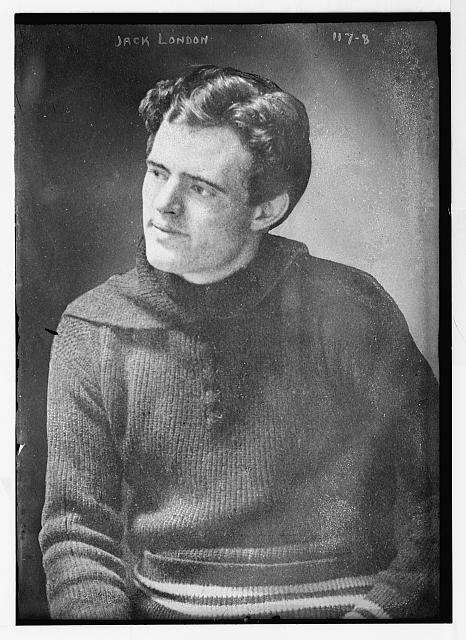

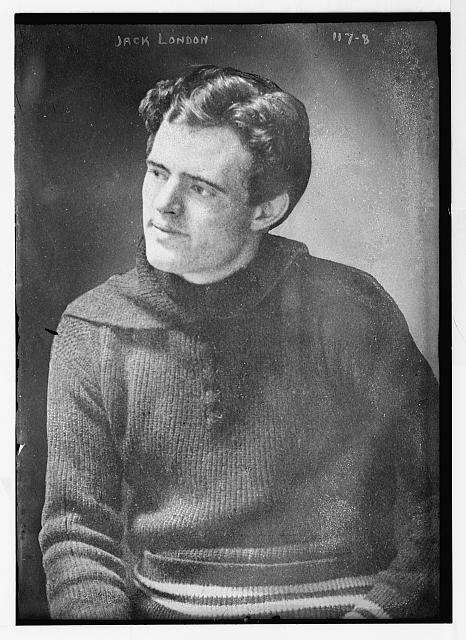

John Griffith Chaney (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to become an international celebrity and earn a large fortune from writing. He was also an innovator in the genre that would later become known as

London was born near Third and Brannan Streets in San Francisco. The house burned down in the fire after the

London was born near Third and Brannan Streets in San Francisco. The house burned down in the fire after the  As a schoolboy, London often studied at

As a schoolboy, London often studied at  While at Berkeley, London continued to study and spend time at Heinold's saloon, where he was introduced to the sailors and adventurers who would influence his writing. In his autobiographical novel, ''

While at Berkeley, London continued to study and spend time at Heinold's saloon, where he was introduced to the sailors and adventurers who would influence his writing. In his autobiographical novel, ''

On July 12, 1897, London (age 21) and his sister's husband Captain Shepard sailed to join the Klondike Gold Rush. This was the setting for some of his first successful stories. London's time in the harsh Klondike, however, was detrimental to his health. Like so many other men who were malnourished in the goldfields, London developed

On July 12, 1897, London (age 21) and his sister's husband Captain Shepard sailed to join the Klondike Gold Rush. This was the setting for some of his first successful stories. London's time in the harsh Klondike, however, was detrimental to his health. Like so many other men who were malnourished in the goldfields, London developed

London married Elizabeth Mae (or May) "Bessie" Maddern on April 7, 1900, the same day ''The Son of the Wolf'' was published. Bess had been part of his circle of friends for a number of years. She was related to stage actresses

London married Elizabeth Mae (or May) "Bessie" Maddern on April 7, 1900, the same day ''The Son of the Wolf'' was published. Bess had been part of his circle of friends for a number of years. She was related to stage actresses

On August 18, 1904, London went with his close friend, the poet

On August 18, 1904, London went with his close friend, the poet

After divorcing Maddern, London married

After divorcing Maddern, London married  Joseph Noel calls the events from 1903 to 1905 "a domestic drama that would have intrigued the pen of an Ibsen.... London's had comedy relief in it and a sort of easy-going romance." In broad outline, London was restless in his first marriage, sought extramarital sexual affairs, and found, in Charmian Kittredge, not only a sexually active and adventurous partner, but his future life-companion. They attempted to have children; one child died at birth, and another pregnancy ended in a miscarriage.

In 1906, London published in ''

Joseph Noel calls the events from 1903 to 1905 "a domestic drama that would have intrigued the pen of an Ibsen.... London's had comedy relief in it and a sort of easy-going romance." In broad outline, London was restless in his first marriage, sought extramarital sexual affairs, and found, in Charmian Kittredge, not only a sexually active and adventurous partner, but his future life-companion. They attempted to have children; one child died at birth, and another pregnancy ended in a miscarriage.

In 1906, London published in ''

Stasz writes that London "had taken fully to heart the vision, expressed in his agrarian fiction, of the land as the closest earthly version of Eden ... he educated himself through the study of agricultural manuals and scientific tomes. He conceived of a system of ranching that today would be praised for its

Stasz writes that London "had taken fully to heart the vision, expressed in his agrarian fiction, of the land as the closest earthly version of Eden ... he educated himself through the study of agricultural manuals and scientific tomes. He conceived of a system of ranching that today would be praised for its

London died November 22, 1916, in a

London died November 22, 1916, in a

London was vulnerable to accusations of plagiarism, both because he was such a conspicuous, prolific, and successful writer and because of his methods of working. He wrote in a letter to Elwyn Hoffman, "expression, you see—with me—is far easier than invention." He purchased plots and novels from the young

London was vulnerable to accusations of plagiarism, both because he was such a conspicuous, prolific, and successful writer and because of his methods of working. He wrote in a letter to Elwyn Hoffman, "expression, you see—with me—is far easier than invention." He purchased plots and novels from the young

London shared common concerns among many European Americans in California about Asian immigration to the United States, Asian immigration, described as "yellow peril, the yellow peril"; he used the latter term as the title of a 1904 essay. This theme was also the subject of a story he wrote in 1910 called "The Unparalleled Invasion". Presented as an historical essay set in the future, the story narrates events between 1976 and 1987, in which China, with an ever-increasing population, is taking over and colonizing its neighbors with the intention of taking over the entire Earth. The western nations respond with biological warfare and bombard China with dozens of the most infectious diseases. On his fears about China, he admits (at the end of "The Yellow Peril"), "it must be taken into consideration that the above postulate is itself a product of Western race-egotism, urged by our belief in our own righteousness and fostered by a faith in ourselves which may be as erroneous as are most fond race fancies."

By contrast, many of London's short stories are notable for their empathetic portrayal of Mexican ("The Mexican"), Asian ("The Chinago"), and Hawaiian ("Koolau the Leper") characters. London's war correspondence from the

London shared common concerns among many European Americans in California about Asian immigration to the United States, Asian immigration, described as "yellow peril, the yellow peril"; he used the latter term as the title of a 1904 essay. This theme was also the subject of a story he wrote in 1910 called "The Unparalleled Invasion". Presented as an historical essay set in the future, the story narrates events between 1976 and 1987, in which China, with an ever-increasing population, is taking over and colonizing its neighbors with the intention of taking over the entire Earth. The western nations respond with biological warfare and bombard China with dozens of the most infectious diseases. On his fears about China, he admits (at the end of "The Yellow Peril"), "it must be taken into consideration that the above postulate is itself a product of Western race-egotism, urged by our belief in our own righteousness and fostered by a faith in ourselves which may be as erroneous as are most fond race fancies."

By contrast, many of London's short stories are notable for their empathetic portrayal of Mexican ("The Mexican"), Asian ("The Chinago"), and Hawaiian ("Koolau the Leper") characters. London's war correspondence from the  In 1996, after the Whitehorse, Yukon, City of Whitehorse,

In 1996, after the Whitehorse, Yukon, City of Whitehorse,

Western writer and historian Dale L. Walker writes:Dale L. Walker, "Jack London: The Stories"

Western writer and historian Dale L. Walker writes:Dale L. Walker, "Jack London: The Stories"

, The World of Jack London London's "strength of utterance" is at its height in his stories, and they are painstakingly well-constructed. "

London's most famous novels are ''

London's most famous novels are ''

(published anonymously, co-authored with

(published in England as ''The Jacket'') * ''

(novelization of a script by Charles Goddard (playwright), Charles Goddard) * ''The Assassination Bureau, Ltd'' (1963)

(left half-finished, completed by Robert L. Fish)

* Mount London, also known as Boundary Peak 100, on the

* Mount London, also known as Boundary Peak 100, on the

Western American Literature Journal: Jack London

The Jack London Online Collection

Site featuring information about Jack London's life and work, and a collection of his writings.

The World of Jack London

Biographical information and writings

Jack London State Historic Park

Guide to the Jack London Papers

at The Bancroft Library

Jack London Collection

a

Sonoma State University Library

Jack London Stories

scanned from original magazines, including the original artwork * 5 shor

from Jack London's writing at California Legacy Project *

Jack London Personal Manuscripts

* {{DEFAULTSORT:London, Jack Jack London, 1876 births 1916 deaths 1906 San Francisco earthquake survivors 19th-century American short story writers 19th-century sailors 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American novelists 20th-century American short story writers 20th-century sailors American atheists American democratic socialists American eugenicists American male non-fiction writers American male novelists American male short story writers American psychological fiction writers American sailors American travel writers American war correspondents Deaths from dysentery Male sailors Members of the Socialist Labor Party of America Military personnel from California People from Glen Ellen, California People from Piedmont, California People involved in plagiarism controversies People of the Klondike Gold Rush People of the Russo-Japanese War Socialist Party of America politicians from California United States Merchant Mariners University of California, Berkeley alumni War correspondents of the Russo-Japanese War Works by Jack London, Writers from Oakland, California Writers from San Francisco

science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel unive ...

.

London was part of the radical literary group "The Crowd" in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

and a passionate advocate of animal rights

Animal rights is the philosophy according to which many or all sentient animals have moral worth that is independent of their utility for humans, and that their most basic interests—such as avoiding suffering—should be afforded the sa ...

, workers’ rights and socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

.Swift, John N. "Jack London's ‘The Unparalleled Invasion’: Germ Warfare, Eugenics, and Cultural Hygiene." American Literary Realism, vol. 35, no. 1, 2002, pp. 59–71. .Hensley, John R. "Eugenics and Social Darwinism in Stanley Waterloo's ‘The Story of Ab’ and Jack London's ‘Before Adam.’" Studies in Popular Culture, vol. 25, no. 1, 2002, pp. 23–37. . London wrote several works dealing with these topics, such as his dystopian novel

Utopian and dystopian fiction are genres of speculative fiction that explore social and political structures. Utopian fiction portrays a setting that agrees with the author's ethos, having various attributes of another reality intended to appeal to ...

''The Iron Heel

''The Iron Heel'' is a political novel in the form of science fiction by American writer Jack London, first published in 1908.Kershaw, Alex. ''Jack London: A Life''. London: HarperCollins, 1997: 164.

Background

The main premise of the book i ...

'', his non-fiction exposé

Expose, exposé, or exposed may refer to:

News sources

* Exposé (journalism), a form of investigative journalism

* '' The Exposé'', a British conspiracist website

Film and TV Film

* ''Exposé'' (film), a 1976 thriller film

* ''Exposed'' (1932 ...

''The People of the Abyss

''The People of the Abyss'' (1903) is a book by Jack London, containing his first-hand account of several weeks spent living in the Whitechapel district of the East End of London in 1902. London attempted to understand the working-class of thi ...

'', ''War of the Classes'', and ''Before Adam

''Before Adam'' is a novel by Jack London, serialized in 1906 and 1907 in ''Everybody's Magazine''. It is the story of a man who dreams he lives the life of an early hominid.

The story offers an early view of human evolution. The majority of t ...

''.

His most famous works include ''The Call of the Wild

''The Call of the Wild'' is a short adventure novel by Jack London, published in 1903 and set in Yukon, Canada, during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush, when strong sled dogs were in high demand. The central character of the novel is a dog named Bu ...

'' and ''White Fang

''White Fang'' is a novel by American author Jack London (1876–1916) — and the name of the book's eponymous character, a wild wolfdog. First serialized in ''Outing'' magazine between May and October 1906, it was published in book form in Oc ...

'', both set in Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

and the Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

during the Klondike Gold Rush, as well as the short stories "To Build a Fire

"To Build a Fire" is a short story by American author Jack London. There are two versions of this story. The first one was published in 1902, and the other was published in 1908. The story written in 1908 has become an often anthologized classic, ...

", "An Odyssey of the North", and "Love of Life". He also wrote about the South Pacific in stories such as "The Pearls of Parlay", and "The Heathen

"The Heathen" is a short story by the American writer Jack London. It was first published in ''Everybody's Magazine'' in August 1910, and later included in the collection of stories by London, ''The Strength of the Strong'', published by Macmillan ...

".

Family

Jack London was born January 12, 1876. His mother, Flora Wellman, was the fifth and youngest child of Pennsylvania Canal builder Marshall Wellman and his first wife, Eleanor Garrett Jones. Marshall Wellman was descended fromThomas Wellman

Thomas Wellman was born in about 1615 in England and died at Lynn, Massachusetts on 10 October 1672. He was among the early settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and progenitor of the Wellman family of New England. At age 21 he traveled from ...

, an early Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

settler in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

.Wellman, Joshua Wyman ''Descendants of Thomas Wellman'' (1918) Arthur Holbrook Wellman, Boston, p. 227 Flora left Ohio and moved to the Pacific coast when her father remarried after her mother died. In San Francisco, Flora worked as a music teacher and spiritualist

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century

The ''long nineteenth century'' i ...

, claiming to channel the spirit of a Sauk chief, Black Hawk.

Biographer Clarice Stasz and others believe London's father was astrologer

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Dif ...

William Chaney. Flora Wellman was living with Chaney in San Francisco when she became pregnant. Whether Wellman and Chaney were legally married is unknown. Stasz notes that in his memoirs, Chaney refers to London's mother Flora Wellman as having been "his wife"; he also cites an advertisement in which Flora called herself "Florence Wellman Chaney".

According to Flora Wellman's account, as recorded in the ''San Francisco Chronicle

The ''San Francisco Chronicle'' is a newspaper serving primarily the San Francisco Bay Area of Northern California. It was founded in 1865 as ''The Daily Dramatic Chronicle'' by teenage brothers Charles de Young and M. H. de Young, Michael H. de ...

'' of June 4, 1875, Chaney demanded that she have an abortion. When she refused, he disclaimed responsibility for the child. In desperation, she shot herself. She was not seriously wounded, but she was temporarily deranged. After giving birth, Flora sent the baby for wet-nursing to Virginia (Jennie) Prentiss, a formerly enslaved African-American woman and a neighbor. Prentiss was an important maternal figure throughout London's life, and he would later refer to her as his primary source of love and affection as a child.

Late in 1876, Flora Wellman married John London, a partially disabled Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

veteran, and brought her baby John, later known as Jack, to live with the newly married couple. The family moved around the San Francisco Bay Area

The San Francisco Bay Area, often referred to as simply the Bay Area, is a populous region surrounding the San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun Bay estuaries in Northern California. The Bay Area is defined by the Association of Bay Area Go ...

before settling in Oakland

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third largest city overall in the Bay A ...

, where London completed public grade school. The Prentiss family moved with the Londons, and remained a stable source of care for the young Jack.

In 1897, when he was 21 and a student at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

, London searched for and read the newspaper accounts of his mother's suicide attempt and the name of his biological father. He wrote to William Chaney, then living in Chicago. Chaney responded that he could not be London's father because he was impotent; he casually asserted that London's mother had relations with other men and averred that she had slandered him when she said he insisted on an abortion. Chaney concluded by saying that he was more to be pitied than London. London was devastated by his father's letter; in the months following, he quit school at Berkeley and went to the Klondike during the gold rush boom.

Early life

London was born near Third and Brannan Streets in San Francisco. The house burned down in the fire after the

London was born near Third and Brannan Streets in San Francisco. The house burned down in the fire after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake

At 05:12 Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (''Extreme''). High-intensity sha ...

; the California Historical Society

The California Historical Society (CHS) is the official historical society of California. It was founded in 1871, by a group of prominent Californian intellectuals at Santa Clara University. It was officially designated as the Californian state hi ...

placed a plaque at the site in 1953. Although the family was working class, it was not as impoverished as London's later accounts claimed. London was largely self-educated.

In 1885, London found and read Ouida

Ouida (; 1 January 1839 – 25 January 1908) was the pseudonym of the English novelist Maria Louise Ramé (although she preferred to be known as Marie Louise de la Ramée). During her career, Ouida wrote more than 40 novels, as well as sh ...

's long Victorian novel ''Signa''. He credited this as the seed of his literary success. In 1886, he went to the Oakland Public Library

The Oakland Public Library is the public library in Oakland, California. Opened in 1878, the Oakland Public Library currently serves the city of Oakland, along with neighboring smaller cities Emeryville and Piedmont. The Oakland Public Library ha ...

and found a sympathetic librarian, Ina Coolbrith

Ina Donna Coolbrith (born Josephine Donna Smith; March 10, 1841 – February 29, 1928) was an American poet, writer, librarian, and a prominent figure in the San Francisco Bay Area literary community. Called the "Sweet Singer of California", sh ...

, who encouraged his learning. (She later became California's first ''poet laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) ...

'' and an important figure in the San Francisco literary community).

In 1889, London began working 12 to 18 hours a day at Hickmott's Cannery. Seeking a way out, he borrowed money from his foster mother Virginia Prentiss, bought the sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

''Razzle-Dazzle'' from an oyster pirate 300px, Oyster pirates on the Chesapeake Bay in 1884

Oyster pirate is a name given to persons who engage in the poaching of oysters. It was a term that became popular on both the West Coast of the United States and the East Coast of the United St ...

named French Frank, and became an oyster pirate himself. In his memoir, ''John Barleycorn

"John Barleycorn" is an English and Scottish folk song listed as number 164 in the Roud Folk Song Index. John Barleycorn, the song's protagonist, is a personification of barley and of the alcoholic beverages made from it: beer and whisky. ...

'', he claims also to have stolen French Frank's mistress Mamie. After a few months, his sloop became damaged beyond repair. London hired on as a member of the California Fish Patrol.

In 1893, he signed on to the sealing schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

''Sophie Sutherland'', bound for the coast of Japan. When he returned, the country was in the grip of the panic of '93 and Oakland

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third largest city overall in the Bay A ...

was swept by labor unrest. After grueling jobs in a jute mill

A jute mill is a factory for processing jute. The first jute mill was established in Dundee, Scotland. The world's largest jute mill was the Adamjee Jute Mills at Narayanganj in Bangladesh. It closed all operations during 2002.

Jack London worked ...

and a street-railway power plant, London joined Coxey's Army

Coxey's Army was a protest march by unemployed workers from the United States, led by Ohio businessman Jacob Coxey. They marched on Washington, D.C. in 1894, the second year of a four-year economic depression that was the worst in United Sta ...

and began his career as a tramp

A tramp is a long-term homeless person who travels from place to place as a vagrant, traditionally walking all year round.

Etymology

Tramp is derived from a Middle English verb meaning to "walk with heavy footsteps" (''cf.'' modern English ''t ...

. In 1894, he spent 30 days for vagrancy in the Erie County Penitentiary at Buffalo, New York. In ''The Road

''The Road'' is a 2006 post-apocalyptic novel by American writer Cormac McCarthy. The book details the grueling journey of a father and his young son over a period of several months across a landscape blasted by an unspecified cataclysm that ha ...

'', he wrote:

After many experiences as a hobo and a sailor, he returned to Oakland and attended Oakland High School. He contributed a number of articles to the high school's magazine, ''The Aegis''. His first published work was "Typhoon off the Coast of Japan", an account of his sailing experiences.

As a schoolboy, London often studied at

As a schoolboy, London often studied at Heinold's First and Last Chance Saloon

Heinold's First and Last Chance is a waterfront Bar (establishment), saloon opened by John (Johnny) M. Heinold in 1883 on Jack London Square in Oakland, California, United States. The name Last Chance Saloon, "First and Last Chance" refers to the t ...

, a port-side bar in Oakland. At 17, he confessed to the bar's owner, John Heinold, his desire to attend university and pursue a career as a writer. Heinold lent London tuition money to attend college.

London desperately wanted to attend the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Merced, Riverside, San Diego, San Francisco, ...

, located in Berkeley. In 1896, after a summer of intense studying to pass certification exams, he was admitted. Financial circumstances forced him to leave in 1897, and he never graduated. No evidence has surfaced that he ever wrote for student publications while studying at Berkeley.

While at Berkeley, London continued to study and spend time at Heinold's saloon, where he was introduced to the sailors and adventurers who would influence his writing. In his autobiographical novel, ''

While at Berkeley, London continued to study and spend time at Heinold's saloon, where he was introduced to the sailors and adventurers who would influence his writing. In his autobiographical novel, ''John Barleycorn

"John Barleycorn" is an English and Scottish folk song listed as number 164 in the Roud Folk Song Index. John Barleycorn, the song's protagonist, is a personification of barley and of the alcoholic beverages made from it: beer and whisky. ...

,'' London mentioned the pub's likeness seventeen times. Heinold's was the place where London met Alexander McLean, a captain known for his cruelty at sea. London based his protagonist Wolf Larsen, in the novel ''The Sea-Wolf

Seawolf, Sea wolf or Sea Wolves may refer to:

Animals

* Sea wolf, a wolf subspecies found in the Vancouver coastal islands

* Seawolf (fish), a marine fish also known as wolffish or sea wolf

* A nickname of the killer whale

* South American se ...

,'' on McLean.

Heinold's First and Last Chance Saloon is now unofficially named Jack London's Rendezvous in his honor.

Gold rush and first success

On July 12, 1897, London (age 21) and his sister's husband Captain Shepard sailed to join the Klondike Gold Rush. This was the setting for some of his first successful stories. London's time in the harsh Klondike, however, was detrimental to his health. Like so many other men who were malnourished in the goldfields, London developed

On July 12, 1897, London (age 21) and his sister's husband Captain Shepard sailed to join the Klondike Gold Rush. This was the setting for some of his first successful stories. London's time in the harsh Klondike, however, was detrimental to his health. Like so many other men who were malnourished in the goldfields, London developed scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

. His gums became swollen, leading to the loss of his four front teeth. A constant gnawing pain affected his hip and leg muscles, and his face was stricken with marks that always reminded him of the struggles he faced in the Klondike. Father William Judge, "The Saint of Dawson", had a facility in Dawson that provided shelter, food and any available medicine to London and others. His struggles there inspired London's short story, "To Build a Fire

"To Build a Fire" is a short story by American author Jack London. There are two versions of this story. The first one was published in 1902, and the other was published in 1908. The story written in 1908 has become an often anthologized classic, ...

" (1902, revised in 1908), which many critics assess as his best.

His landlords in Dawson were mining engineers Marshall Latham Bond

Marshall Latham Bond was one of two brothers who were Jack London's landlords and among his employers during the autumn of 1897 and the spring of 1898 during the Klondike Gold Rush. They were the owners of the dog that London fictionalized as Bu ...

and Louis Whitford Bond, educated at the Bachelor's level at the Sheffield Scientific School

Sheffield Scientific School was founded in 1847 as a school of Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut, for instruction in science and engineering. Originally named the Yale Scientific School, it was renamed in 1861 in honor of Joseph E. Sheffield, ...

at Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

and at the Master's level at Stanford

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is considere ...

, respectively. The brothers' father, Judge Hiram Bond

Hiram Bond was born May 10, 1838 in Farmersville, Cattaraugus County, New York and died in Seattle March 29, 1906. He was a corporate lawyer, investment banker and an investor in various businesses including gold mining. His family are descended ...

, was a wealthy mining investor. While the Bond brothers were at Stanford, Hiram at the suggestion of his brother bought the New Park Estate at Santa Clara as well as a local bank. The Bonds, especially Hiram, were active Republicans. Marshall Bond's diary mentions friendly sparring with London on political issues as a camp pastime.

London left Oakland with a social conscience

A social conscience is "a sense of responsibility or concern for the problems and injustices of society".

While our conscience is related to moral conduct in our day-to-day lives with respect to individuals, social conscience is concerned with th ...

and socialist leanings; he returned to become an activist for socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

. He concluded that his only hope of escaping the work "trap" was to get an education and "sell his brains". He saw his writing as a business, his ticket out of poverty and, he hoped, as a means of beating the wealthy at their own game.

On returning to California in 1898, London began working to get published, a struggle described in his novel ''Martin Eden

''Martin Eden'' is a 1909 novel by American author Jack London about a young proletarian autodidact struggling to become a writer. It was first serialized in ''The Pacific Monthly'' magazine from September 1908 to September 1909 and then publish ...

'' (serialized in 1908, published in 1909). His first published story since high school was "To the Man On Trail", which has frequently been collected in anthologies. When '' The Overland Monthly'' offered him only five dollars for it—and was slow paying—London came close to abandoning his writing career. In his words, "literally and literarily I was saved" when '' The Black Cat'' accepted his story "A Thousand Deaths" and paid him $40—the "first money I ever received for a story".

London began his writing career just as new printing technologies enabled lower-cost production of magazines. This resulted in a boom in popular magazines aimed at a wide public audience and a strong market for short fiction. In 1900, he made $2,500 in writing, about $ in today's currency.

Among the works he sold to magazines was a short story known as either "Diable" (1902) or "Bâtard" (1904), two editions of the same basic story. London received $141.25 for this story on May 27, 1902. In the text, a cruel French Canadian

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

brutalizes his dog, and the dog retaliates and kills the man. London told some of his critics that man's actions are the main cause of the behavior of their animals, and he would show this famously in another story, ''The Call of the Wild

''The Call of the Wild'' is a short adventure novel by Jack London, published in 1903 and set in Yukon, Canada, during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush, when strong sled dogs were in high demand. The central character of the novel is a dog named Bu ...

''.

In early 1903, London sold ''The Call of the Wild'' to ''The Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine, currently published six times a year. It was issued weekly under this title from 1897 until 1963, then every two weeks until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely c ...

'' for $750 and the book rights to Macmillan. Macmillan's promotional campaign propelled it to swift success.

While living at his rented villa on Lake Merritt

Lake Merritt is a large tidal lagoon in the center of Oakland, California, just east of Downtown. It is surrounded by parkland and city neighborhoods. It is historically significant as the United States' first official wildlife refuge, designate ...

in Oakland, California, London met poet George Sterling

George Sterling (December 1, 1869 – November 17, 1926) was an American writer based in the San Francisco, California Bay Area and Carmel-by-the-Sea. He was considered a prominent poet and playwright and proponent of Bohemianism during the f ...

; in time they became best friends. In 1902, Sterling helped London find a home closer to his own in nearby Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

. In his letters London addressed Sterling as "Greek", owing to Sterling's aquiline nose

An aquiline nose (also called a Roman nose) is a human nose with a prominent bridge, giving it the appearance of being curved or slightly bent. The word ''aquiline'' comes from the Latin word ''aquilinus'' ("eagle-like"), an allusion to the curved ...

and classical profile, and he signed them as "Wolf". London was later to depict Sterling as Russ Brissenden in his autobiographical novel ''Martin Eden'' (1910) and as Mark Hall in '' The Valley of the Moon'' (1913).

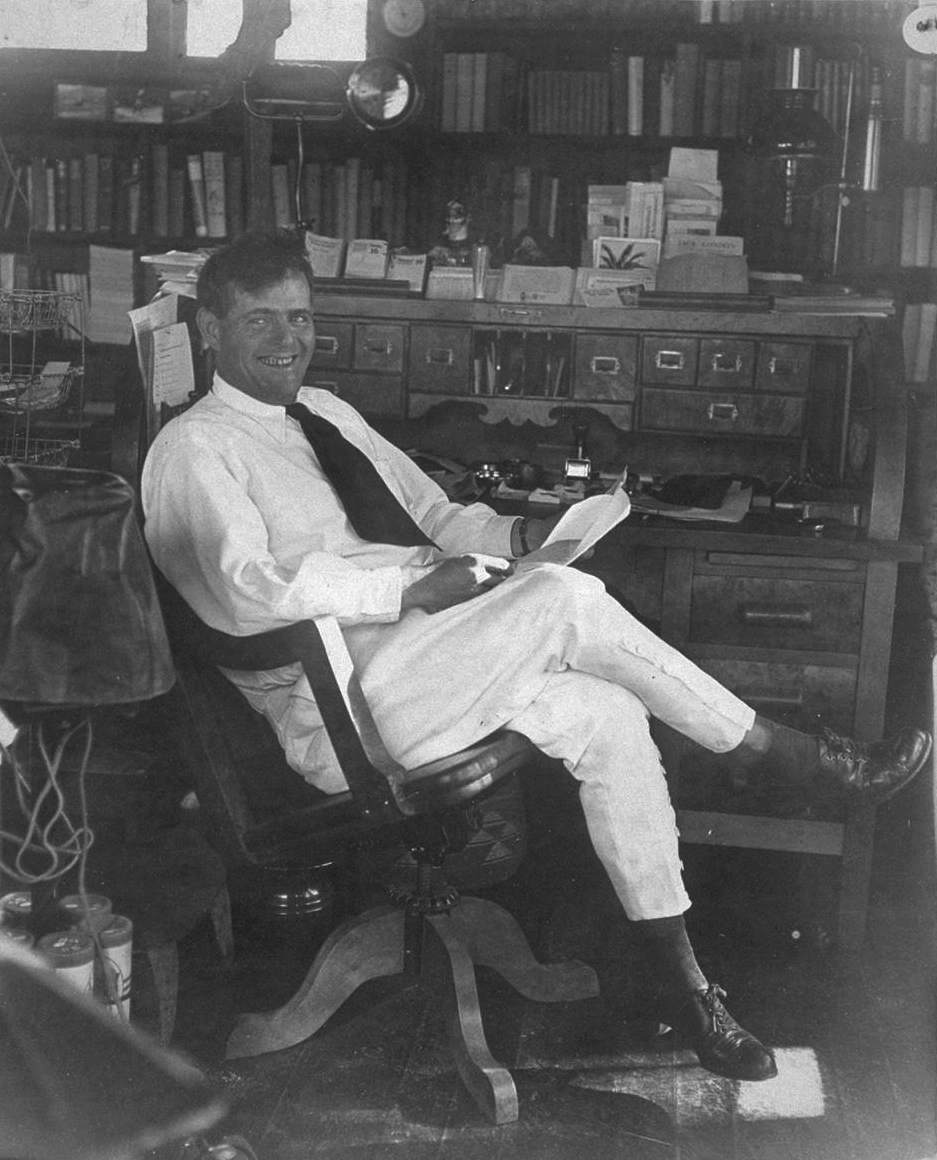

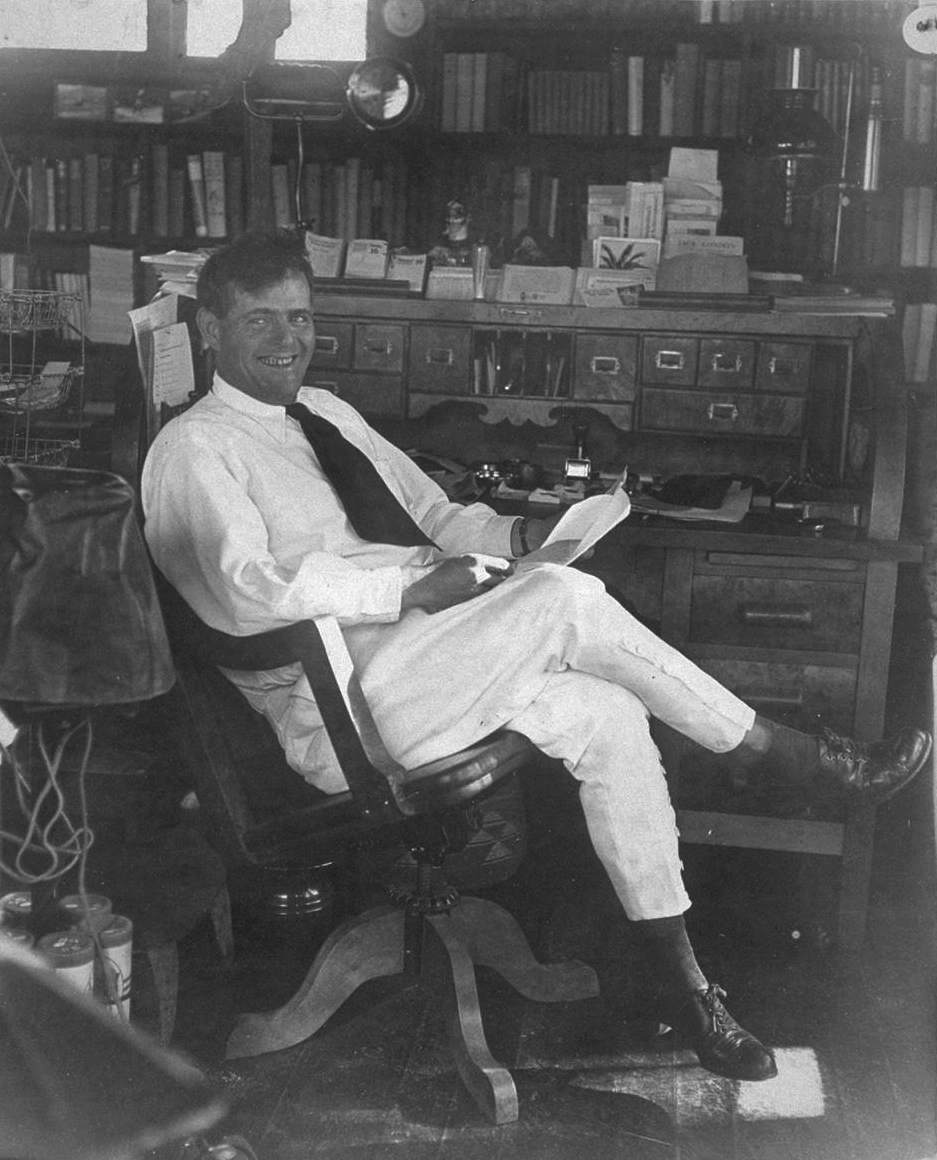

In later life London indulged his wide-ranging interests by accumulating a personal library of 15,000 volumes. He referred to his books as "the tools of my trade".

First marriage (1900–1904)

London married Elizabeth Mae (or May) "Bessie" Maddern on April 7, 1900, the same day ''The Son of the Wolf'' was published. Bess had been part of his circle of friends for a number of years. She was related to stage actresses

London married Elizabeth Mae (or May) "Bessie" Maddern on April 7, 1900, the same day ''The Son of the Wolf'' was published. Bess had been part of his circle of friends for a number of years. She was related to stage actresses Minnie Maddern Fiske

Minnie Maddern Fiske (born Marie Augusta Davey; December 19, 1865 – February 15, 1932), but often billed simply as Mrs. Fiske, was one of the leading American actresses of the late 19th and early 20th century. She also spearheaded the fig ...

and Emily Stevens. Stasz says, "Both acknowledged publicly that they were not marrying out of love, but from friendship and a belief that they would produce sturdy children." Kingman says, "they were comfortable together... Jack had made it clear to Bessie that he did not love her, but that he liked her enough to make a successful marriage."

London met Bessie through his friend at Oakland High School, Fred Jacobs; she was Fred's fiancée. Bessie, who tutored at Anderson's University Academy in Alameda California, tutored Jack in preparation for his entrance exams for the University of California at Berkeley in 1896. Jacobs was killed aboard the ''Scandia'' in 1897, but Jack and Bessie continued their friendship, which included taking photos and developing the film together. This was the beginning of Jack's passion for photography.

During the marriage, London continued his friendship with Anna Strunsky

Anna Strunsky Walling (March 21, 1877 – February 25, 1964) was known as an early 20th-century Jewish-American author and advocate of socialism based in San Francisco, California, and New York City. She was primarily a novelist, but also wrote a ...

, co-authoring '' The Kempton-Wace Letters'', an epistolary novel

An epistolary novel is a novel written as a series of letters. The term is often extended to cover novels that intersperse documents of other kinds with the letters, most commonly diary entries and newspaper clippings, and sometimes considered ...

contrasting two philosophies of love. Anna, writing "Dane Kempton's" letters, arguing for a romantic view of marriage, while London, writing "Herbert Wace's" letters, argued for a scientific view, based on Darwinism

Darwinism is a scientific theory, theory of Biology, biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of smal ...

and eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

. In the novel, his fictional character contrasted two women he had known.

London's pet name for Bess was "Mother-Girl" and Bess's for London was "Daddy-Boy". Their first child, Joan Joan may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Joan (given name), including a list of women, men and fictional characters

*:Joan of Arc, a French military heroine

* Joan (surname)

Weather events

*Tropical Storm Joan (disambiguation), multip ...

, was born on January 15, 1901, and their second, Bessie "Becky" (also reported as Bess), on October 20, 1902. Both children were born in Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, California. Here London wrote one of his most celebrated works, ''The Call of the Wild

''The Call of the Wild'' is a short adventure novel by Jack London, published in 1903 and set in Yukon, Canada, during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush, when strong sled dogs were in high demand. The central character of the novel is a dog named Bu ...

.''

While London had pride in his children, the marriage was strained. Kingman says that by 1903 the couple were close to separation as they were "extremely incompatible". "Jack was still so kind and gentle with Bessie that when Cloudsley Johns was a house guest in February 1903 he didn't suspect a breakup of their marriage."

London reportedly complained to friends Joseph Noel and George Sterling:

Stasz writes that these were "code words for ess'sfear that ackwas consorting with prostitutes and might bring home venereal disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral se ...

."

On July 24, 1903, London told Bessie he was leaving and moved out. During 1904, London and Bess negotiated the terms of a divorce, and the decree was granted on November 11, 1904.

War correspondent (1904)

London accepted an assignment of the ''San Francisco Examiner

The ''San Francisco Examiner'' is a newspaper distributed in and around San Francisco, California, and published since 1863.

Once self-dubbed the "Monarch of the Dailies" by then-owner William Randolph Hearst, and flagship of the Hearst Corporat ...

'' to cover the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

in early 1904, arriving in Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

on January 25, 1904. He was arrested by Japanese authorities in Shimonoseki

is a city located in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan. With a population of 265,684, it is the largest city in Yamaguchi Prefecture and the fifth-largest city in the Chūgoku region. It is located at the southwestern tip of Honshu facing the Tsushim ...

, but released through the intervention of American ambassador Lloyd Griscom. After travelling to Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

, he was again arrested by Japanese authorities for straying too close to the border with Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manc ...

without official permission, and was sent back to Seoul

Seoul (; ; ), officially known as the Seoul Special City, is the capital and largest metropolis of South Korea.Before 1972, Seoul was the ''de jure'' capital of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) as stated iArticle 103 ...

. Released again, London was permitted to travel with the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor o ...

to the border, and to observe the Battle of the Yalu

The Battle of the Yalu River (; ja, 黄海海戦, translit=Kōkai-kaisen; ) was the largest naval engagement of the First Sino-Japanese War, and took place on 17 September 1894, the day after the Japanese victory at the land Battle of Pyongy ...

.

London asked William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

, the owner of the ''San Francisco Examiner'', to be allowed to transfer to the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: Ру́сская импера́торская а́рмия, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

, where he felt that restrictions on his reporting and his movements would be less severe. However, before this could be arranged, he was arrested for a third time in four months, this time for assaulting his Japanese assistants, whom he accused of stealing the fodder for his horse. Released through the personal intervention of President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, London departed the front in June 1904.

Bohemian Club

On August 18, 1904, London went with his close friend, the poet

On August 18, 1904, London went with his close friend, the poet George Sterling

George Sterling (December 1, 1869 – November 17, 1926) was an American writer based in the San Francisco, California Bay Area and Carmel-by-the-Sea. He was considered a prominent poet and playwright and proponent of Bohemianism during the f ...

, to "Summer High Jinks" at the Bohemian Grove

Bohemian Grove is a restricted 2,700-acre (1,100 ha) campground at 20601 Bohemian Avenue, in Monte Rio, California, United States, belonging to a private San Francisco–based gentlemen's club known as the Bohemian Club. In mid-July each year, ...

. London was elected to honorary membership in the Bohemian Club and took part in many activities. Other noted members of the Bohemian Club during this time included Ambrose Bierce

Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce (June 24, 1842 – ) was an American short story writer, journalist, poet, and American Civil War veteran. His book ''The Devil's Dictionary'' was named as one of "The 100 Greatest Masterpieces of American Literature" by t ...

, Gelett Burgess

Frank Gelett Burgess (January 30, 1866 – September 18, 1951) was an American artist, art critic, poet, author and humorist. An important figure in the San Francisco Bay Area literary renaissance of the 1890s, particularly through his iconoclas ...

, Allan Dunn, John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologist, a ...

, Frank Norris

Benjamin Franklin Norris Jr. (March 5, 1870 – October 25, 1902) was an American journalist and novelist during the Progressive Era, whose fiction was predominantly in the naturalist genre. His notable works include '' McTeague: A Story of San ...

, and Herman George Scheffauer

Herman George Scheffauer (born February 3, 1876, San Francisco, California – died October 7, 1927, Berlin) was a German-American poet, architect, writer, dramatist, journalist, and translator.

San Francisco childhood

Very little is known abou ...

.

Beginning in December 1914, London worked on ''The Acorn Planter, A California Forest Play'', to be performed as one of the annual Grove Plays, but it was never selected. It was described as too difficult to set to music. London published ''The Acorn Planter'' in 1916.

Second marriage

After divorcing Maddern, London married

After divorcing Maddern, London married Charmian Kittredge

Charmian London ( née Kittredge; November 27, 1871 – January 14, 1955) was an American writer and the second wife of Jack London.

Early life

"Clara" Charmian Kittredge was born to poet and writer Dayelle "Daisy" Wiley and California hotelier ...

in 1905. London had been introduced to Kittredge in 1900 by her aunt Netta Eames, who was an editor at ''Overland Monthly'' magazine in San Francisco. The two met prior to his first marriage but became lovers years later after Jack and Bessie London visited Wake Robin, Netta Eames' Sonoma County resort, in 1903. London was injured when he fell from a buggy, and Netta arranged for Charmian to care for him. The two developed a friendship, as Charmian, Netta, her husband Roscoe, and London were politically aligned with socialist causes. At some point the relationship became romantic, and Jack divorced his wife to marry Charmian, who was five years his senior.

Biographer Russ Kingman called Charmian "Jack's soul-mate, always at his side, and a perfect match." Their time together included numerous trips, including a 1907 cruise on the yacht ''Snark

Snark may refer to:

Fictional creatures

* Snark (Lewis Carroll), a fictional animal species in Lewis Carroll's ''The Hunting of the Snark'' (1876)

* Zn'rx, a race of fictional aliens in Marvel Comics publications, commonly referred to as "Snark ...

'' to Hawaii and Australia. Many of London's stories are based on his visits to Hawaii, the last one for 10 months beginning in December 1915.

The couple also visited Goldfield, Nevada, in 1907, where they were guests of the Bond brothers, London's Dawson City landlords. The Bond brothers were working in Nevada as mining engineers.

London had contrasted the concepts of the "Mother Girl" and the "Mate Woman" in ''The Kempton-Wace Letters.'' His pet name for Bess had been "Mother-Girl;" his pet name for Charmian was "Mate-Woman." Charmian's aunt and foster mother, a disciple of Victoria Woodhull

Victoria Claflin Woodhull, later Victoria Woodhull Martin (September 23, 1838 – June 9, 1927), was an American leader of the women's suffrage movement who ran for President of the United States in the 1872 election. While many historians ...

, had raised her without prudishness. Every biographer alludes to Charmian's uninhibited sexuality.

Joseph Noel calls the events from 1903 to 1905 "a domestic drama that would have intrigued the pen of an Ibsen.... London's had comedy relief in it and a sort of easy-going romance." In broad outline, London was restless in his first marriage, sought extramarital sexual affairs, and found, in Charmian Kittredge, not only a sexually active and adventurous partner, but his future life-companion. They attempted to have children; one child died at birth, and another pregnancy ended in a miscarriage.

In 1906, London published in ''

Joseph Noel calls the events from 1903 to 1905 "a domestic drama that would have intrigued the pen of an Ibsen.... London's had comedy relief in it and a sort of easy-going romance." In broad outline, London was restless in his first marriage, sought extramarital sexual affairs, and found, in Charmian Kittredge, not only a sexually active and adventurous partner, but his future life-companion. They attempted to have children; one child died at birth, and another pregnancy ended in a miscarriage.

In 1906, London published in ''Collier's

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened in 1905 to ''Collie ...

'' magazine his eye-witness report of the San Francisco earthquake

At 05:12 Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (''Extreme''). High-intensity sha ...

.

Beauty Ranch (1905–1916)

In 1905, London purchased a ranch inGlen Ellen

Glen Ellen is a census-designated place (CDP) in Sonoma Valley, Sonoma County, California, United States. The population was 784 at the 2010 census, down from 992 at the 2000 census. Glen Ellen is the location of Jack London State Historic P ...

, Sonoma County

Sonoma County () is a county (United States), county located in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 United States Census, its population was 488,863. Its county seat and largest city is Santa Rosa, California, Santa Rosa. It is to the n ...

, California, on the eastern slope of Sonoma Mountain

Sonoma Mountain is a prominent landform within the Sonoma Mountains of southern Sonoma County, California. At an elevation of , Sonoma Mountain offers expansive views of the Pacific Ocean to the west and the Sonoma Valley to the east. In fact, ...

. He wrote: "Next to my wife, the ranch is the dearest thing in the world to me." He desperately wanted the ranch to become a successful business enterprise. Writing, always a commercial enterprise with London, now became even more a means to an end: "I write for no other purpose than to add to the beauty that now belongs to me. I write a book for no other reason than to add three or four hundred acres to my magnificent estate."

Stasz writes that London "had taken fully to heart the vision, expressed in his agrarian fiction, of the land as the closest earthly version of Eden ... he educated himself through the study of agricultural manuals and scientific tomes. He conceived of a system of ranching that today would be praised for its

Stasz writes that London "had taken fully to heart the vision, expressed in his agrarian fiction, of the land as the closest earthly version of Eden ... he educated himself through the study of agricultural manuals and scientific tomes. He conceived of a system of ranching that today would be praised for its ecological wisdom

Ecosophy or ecophilosophy (a portmanteau of ecological philosophy) is a philosophy of ecological harmony or equilibrium. The term was coined by the French post-structuralist philosopher and psychoanalyst Félix Guattari and the Norwegian father ...

." He was proud to own the first concrete silo

A silo (from the Greek σιρός – ''siros'', "pit for holding grain") is a structure for storing bulk materials. Silos are used in agriculture to store fermented feed known as silage, not to be confused with a grain bin, which is used t ...

in California. He hoped to adapt the wisdom of Asian sustainable agriculture

Sustainable agriculture is farming in sustainable ways meeting society's present food and textile needs, without compromising the ability for current or future generations to meet their needs. It can be based on an understanding of ecosystem ser ...

to the United States. He hired both Italian and Chinese stonemasons, whose distinctly different styles are obvious.

The ranch was an economic failure. Sympathetic observers such as Stasz treat his projects as potentially feasible, and ascribe their failure to bad luck or to being ahead of their time. Unsympathetic historians such as Kevin Starr

Kevin Owen Starr (September 3, 1940 – January 14, 2017) was an American historian and California's state librarian, best known for his multi-volume series on the history of California, collectively called "Americans and the California Dream." ...

suggest that he was a bad manager, distracted by other concerns and impaired by his alcoholism. Starr notes that London was absent from his ranch about six months a year between 1910 and 1916 and says, "He liked the show of managerial power, but not grinding attention to detail .... London's workers laughed at his efforts to play big-time rancher nd consideredthe operation a rich man's hobby."

London spent $80,000 ($ in current value) to build a stone mansion called Wolf House on the property. Just as the mansion was nearing completion, two weeks before the Londons planned to move in, it was destroyed by fire.

London's last visit to Hawaii, () beginning in December 1915, lasted eight months. He met with Duke Kahanamoku, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana'ole, Queen Lili'uokalani and many others, before returning to his ranch in July 1916. He was suffering from kidney failure

Kidney failure, also known as end-stage kidney disease, is a medical condition in which the kidneys can no longer adequately filter waste products from the blood, functioning at less than 15% of normal levels. Kidney failure is classified as eit ...

, but he continued to work.

The ranch (abutting stone remnants of Wolf House) is now a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

and is protected in Jack London State Historic Park

Jack London State Historic Park, also known as Jack London Home and Ranch, is a California State Historic Park near Glen Ellen, California, United States, situated on the eastern slope of Sonoma Mountain. It includes the ruins of a house burned ...

.

Animal activism

London witnessed animal cruelty in the training of circus animals, and his subsequent novels ''Jerry of the Islands

''Jerry of the Islands: A True Dog Story'' is a novel by American writer Jack London. ''Jerry of the Islands'' was initially published in 1917 and is one of the last works by Jack London. The novel is set on the island of Malaita, a part of the S ...

'' and ''Michael, Brother of Jerry

''Michael, Brother of Jerry'' is a novel by Jack London released in 1917. This novel is loosely connected to his previous novel ''Jerry of the Islands'', also released in 1917. Each book tells the story of one of two dog siblings, Jerry and Micha ...

'' included a foreword entreating the public to become more informed about this practice. In 1918, the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and the American Humane Education Society teamed up to create the Jack London Club, which sought to inform the public about cruelty to circus animals and encourage them to protest this establishment. Support from Club members led to a temporary cessation of trained animal acts at Ringling-Barnum and Bailey in 1925.

Death

London died November 22, 1916, in a

London died November 22, 1916, in a sleeping porch

A sleeping porch is a deck or balcony, sometimes screened or otherwise enclosed with screened windows,scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

in the Klondike. Additionally, during travels on the ''Snark'', he and Charmian picked up unspecified tropical infections and diseases, including yaws

Yaws is a tropical infection of the skin, bones, and joints caused by the spirochete bacterium ''Treponema pallidum pertenue''. The disease begins with a round, hard swelling of the skin, in diameter. The center may break open and form an ulce ...

. At the time of his death, he suffered from dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

, late-stage alcoholism, and uremia

Uremia is the term for high levels of urea in the blood. Urea is one of the primary components of urine. It can be defined as an excess of amino acid and protein metabolism end products, such as urea and creatinine, in the blood that would be no ...

; he was in extreme pain and taking morphine

Morphine is a strong opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin in poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as a analgesic, pain medication, and is also commonly used recreational drug, recreationally, or to make ...

and opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

, both common, over-the-counter drugs

Over-the-counter (OTC) drugs are medicines sold directly to a consumer without a requirement for a prescription from a healthcare professional, as opposed to prescription drugs, which may be supplied only to consumers possessing a valid prescr ...

at the time.

London's ashes were buried on his property not far from the Wolf House. London's funeral took place on November 26, 1916, attended only by close friends, relatives, and workers of the property. In accordance with his wishes, he was cremated and buried next to some pioneer children, under a rock that belonged to the Wolf House. After Charmian's death in 1955, she was also cremated and then buried with her husband in the same spot that her husband chose. The grave is marked by a mossy boulder. The buildings and property were later preserved as Jack London State Historic Park

Jack London State Historic Park, also known as Jack London Home and Ranch, is a California State Historic Park near Glen Ellen, California, United States, situated on the eastern slope of Sonoma Mountain. It includes the ruins of a house burned ...

, in Glen Ellen

Glen Ellen is a census-designated place (CDP) in Sonoma Valley, Sonoma County, California, United States. The population was 784 at the 2010 census, down from 992 at the 2000 census. Glen Ellen is the location of Jack London State Historic P ...

, California.

Suicide debate

Because he was using morphine, many older sources describe London's death as a suicide, and some still do. This conjecture appears to be a rumor, or speculation based on incidents in his fiction writings. His death certificate gives the cause asuremia

Uremia is the term for high levels of urea in the blood. Urea is one of the primary components of urine. It can be defined as an excess of amino acid and protein metabolism end products, such as urea and creatinine, in the blood that would be no ...

, following acute renal colic

Renal colic is a type of abdominal pain commonly caused by obstruction of ureter from dislodged kidney stones. The most frequent site of obstruction is the vesico-ureteric junction (VUJ), the narrowest point of the upper urinary tract. Acute ob ...

.

The biographer Stasz writes, "Following London's death, for a number of reasons, a biographical myth developed in which he has been portrayed as an alcoholic womanizer who committed suicide. Recent scholarship based upon firsthand documents challenges this caricature." Most biographers, including Russ Kingman, now agree he died of uremia aggravated by an accidental morphine overdose.

London's fiction featured several suicides. In his autobiographical memoir ''John Barleycorn

"John Barleycorn" is an English and Scottish folk song listed as number 164 in the Roud Folk Song Index. John Barleycorn, the song's protagonist, is a personification of barley and of the alcoholic beverages made from it: beer and whisky. ...

'', he claims, as a youth, to have drunkenly stumbled overboard into the San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water from a ...

, "some maundering fancy of going out with the tide suddenly obsessed me". He said he drifted and nearly succeeded in drowning before sobering up and being rescued by fishermen. In the dénouement of ''The Little Lady of the Big House

''The Little Lady of the Big House'' (1915) is a novel by American writer Jack London. It was his last novel to be published during his lifetime.

Plot

The story concerns a love triangle. The protagonist, Dick Forrest, is a rancher with a poetic ...

'', the heroine, confronted by the pain of a mortal gunshot wound, undergoes a physician-assisted suicide by morphine. Also, in ''Martin Eden

''Martin Eden'' is a 1909 novel by American author Jack London about a young proletarian autodidact struggling to become a writer. It was first serialized in ''The Pacific Monthly'' magazine from September 1908 to September 1909 and then publish ...

'', the principal protagonist, who shares certain characteristics with London, drowns himself.

Plagiarism accusations

London was vulnerable to accusations of plagiarism, both because he was such a conspicuous, prolific, and successful writer and because of his methods of working. He wrote in a letter to Elwyn Hoffman, "expression, you see—with me—is far easier than invention." He purchased plots and novels from the young

London was vulnerable to accusations of plagiarism, both because he was such a conspicuous, prolific, and successful writer and because of his methods of working. He wrote in a letter to Elwyn Hoffman, "expression, you see—with me—is far easier than invention." He purchased plots and novels from the young Sinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American writer and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was ...

and used incidents from newspaper clippings as writing material.

In July 1901, two pieces of fiction appeared within the same month: London's " Moon-Face", in the ''San Francisco Argonaut,'' and Frank Norris

Benjamin Franklin Norris Jr. (March 5, 1870 – October 25, 1902) was an American journalist and novelist during the Progressive Era, whose fiction was predominantly in the naturalist genre. His notable works include '' McTeague: A Story of San ...

' "The Passing of Cock-eye Blacklock", in ''Century Magazine

''The Century Magazine'' was an illustrated monthly magazine first published in the United States in 1881 by The Century Company of New York City, which had been bought in that year by Roswell Smith and renamed by him after the Century Associati ...

''. Newspapers showed the similarities between the stories, which London said were "quite different in manner of treatment, utpatently the same in foundation and motive." London explained both writers based their stories on the same newspaper account. A year later, it was discovered that Charles Forrest McLean had published a fictional story also based on the same incident.

Egerton Ryerson Young claimed ''The Call of the Wild

''The Call of the Wild'' is a short adventure novel by Jack London, published in 1903 and set in Yukon, Canada, during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush, when strong sled dogs were in high demand. The central character of the novel is a dog named Bu ...

'' (1903) was taken from Young's book ''My Dogs in the Northland'' (1902). London acknowledged using it as a source and claimed to have written a letter to Young thanking him.

In 1906, the ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under publi ...

'' published "deadly parallel" columns showing eighteen passages from London's short story "Love of Life" side by side with similar passages from a nonfiction article by Augustus Biddle and J. K. Macdonald, titled "Lost in the Land of the Midnight Sun". London noted the ''World'' did not accuse him of "plagiarism", but only of "identity of time and situation", to which he defiantly "pled guilty".

The most serious charge of plagiarism was based on London's "The Bishop's Vision", Chapter 7 of his novel ''The Iron Heel

''The Iron Heel'' is a political novel in the form of science fiction by American writer Jack London, first published in 1908.Kershaw, Alex. ''Jack London: A Life''. London: HarperCollins, 1997: 164.

Background

The main premise of the book i ...

'' (1908). The chapter is nearly identical to an ironic essay that Frank Harris

Frank Harris (14 February 1855 – 26 August 1931) was an Irish-American editor, novelist, short story writer, journalist and publisher, who was friendly with many well-known figures of his day.

Born in Ireland, he emigrated to the United State ...

published in 1901, titled "The Bishop of London and Public Morality". Harris was incensed and suggested he should receive 1/60th of the royalties from ''The Iron Heel,'' the disputed material constituting about that fraction of the whole novel. London insisted he had clipped a reprint of the article, which had appeared in an American newspaper, and believed it to be a genuine speech delivered by the Bishop of London.

Views

Atheism

London was an atheist. He is quoted as saying, "I believe that when I am dead, I am dead. I believe that with my death I am just as much obliterated as the last mosquito you and I squashed."Socialism

London wrote from a socialist viewpoint, which is evident in his novel ''The Iron Heel

''The Iron Heel'' is a political novel in the form of science fiction by American writer Jack London, first published in 1908.Kershaw, Alex. ''Jack London: A Life''. London: HarperCollins, 1997: 164.

Background

The main premise of the book i ...

''. Neither a theorist nor an intellectual socialist, London's socialism grew out of his life experience. As London explained in his essay, "How I Became a Socialist", his views were influenced by his experience with people at the bottom of the social pit. His optimism and individualism faded, and he vowed never to do more hard physical work than necessary. He wrote that his individualism was hammered out of him, and he was politically reborn. He often closed his letters "Yours for the Revolution."

London joined the Socialist Labor Party in April 1896. In the same year, the ''San Francisco Chronicle'' published a story about the twenty-year-old London's giving nightly speeches in Oakland's Frank H. Ogawa Plaza, City Hall Park, an activity he was arrested for a year later. In 1901, he left the Socialist Labor Party and joined the new Socialist Party of America. He ran unsuccessfully as the high-profile Socialist candidate for mayor of Oakland in 1901 (receiving 245 votes) and 1905 (improving to 981 votes), toured the country lecturing on socialism in 1906, and published two collections of essays about socialism: ''War of the Classes'' (1905) and ''Revolution, and other Essays'' (1906).

Stasz notes that "London regarded the Industrial Workers of the World, Wobblies as a welcome addition to the Socialist cause, although he never joined them in going so far as to recommend sabotage." Stasz mentions a personal meeting between London and Big Bill Haywood in 1912.

In his late (1913) book ''The Cruise of the Snark'', London writes about appeals to him for membership of the ''Snarks crew from office workers and other "toilers" who longed for escape from the cities, and of being cheated by workmen.

In his Glen Ellen ranch years, London felt some ambivalence toward socialism and complained about the "inefficient Italian labourers" in his employ. In 1916, he resigned from the Glen Ellen chapter of the Socialist Party, but stated emphatically he did so "because of its lack of fire and fight, and its loss of emphasis on the class struggle." In an unflattering portrait of London's ranch days, California cultural historian Kevin Starr

Kevin Owen Starr (September 3, 1940 – January 14, 2017) was an American historian and California's state librarian, best known for his multi-volume series on the history of California, collectively called "Americans and the California Dream." ...

refers to this period as "post-socialist" and says "... by 1911 ... London was more bored by the class struggle than he cared to admit."

Race

London shared common concerns among many European Americans in California about Asian immigration to the United States, Asian immigration, described as "yellow peril, the yellow peril"; he used the latter term as the title of a 1904 essay. This theme was also the subject of a story he wrote in 1910 called "The Unparalleled Invasion". Presented as an historical essay set in the future, the story narrates events between 1976 and 1987, in which China, with an ever-increasing population, is taking over and colonizing its neighbors with the intention of taking over the entire Earth. The western nations respond with biological warfare and bombard China with dozens of the most infectious diseases. On his fears about China, he admits (at the end of "The Yellow Peril"), "it must be taken into consideration that the above postulate is itself a product of Western race-egotism, urged by our belief in our own righteousness and fostered by a faith in ourselves which may be as erroneous as are most fond race fancies."

By contrast, many of London's short stories are notable for their empathetic portrayal of Mexican ("The Mexican"), Asian ("The Chinago"), and Hawaiian ("Koolau the Leper") characters. London's war correspondence from the

London shared common concerns among many European Americans in California about Asian immigration to the United States, Asian immigration, described as "yellow peril, the yellow peril"; he used the latter term as the title of a 1904 essay. This theme was also the subject of a story he wrote in 1910 called "The Unparalleled Invasion". Presented as an historical essay set in the future, the story narrates events between 1976 and 1987, in which China, with an ever-increasing population, is taking over and colonizing its neighbors with the intention of taking over the entire Earth. The western nations respond with biological warfare and bombard China with dozens of the most infectious diseases. On his fears about China, he admits (at the end of "The Yellow Peril"), "it must be taken into consideration that the above postulate is itself a product of Western race-egotism, urged by our belief in our own righteousness and fostered by a faith in ourselves which may be as erroneous as are most fond race fancies."

By contrast, many of London's short stories are notable for their empathetic portrayal of Mexican ("The Mexican"), Asian ("The Chinago"), and Hawaiian ("Koolau the Leper") characters. London's war correspondence from the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

, as well as his unfinished novel ''Cherry'', show he admired much about Japanese customs and capabilities. London's writings have been popular among the Japanese, who believe he portrayed them positively.Jeanne Campbell Reesman, ''Jack London's Racial Lives: A Critical Biography'', University of Georgia Press, 2009, pp. 323–24

In "Koolau the Leper", London describes Koolau, who is a Hawaiian leper—and thus a very different sort of "superman" than Martin Eden—and who fights off an entire cavalry troop to elude capture, as "indomitable spiritually—a ... magnificent rebel". This character is based on Hawaiian leper Kaluaikoolau, who in 1893 Leper War on Kauaʻi, revolted and resisted capture from forces of the Provisional Government of Hawaii in the Kalalau Valley.

Those who defend London against charges of racism cite the letter he wrote to the ''Japanese-American Commercial Weekly'' in 1913:

In 1996, after the Whitehorse, Yukon, City of Whitehorse,

In 1996, after the Whitehorse, Yukon, City of Whitehorse, Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

, renamed a street in honor of London, protests over London's alleged racism forced the city to change the name of "Jack London Boulevard" back to "Two-mile Hill".

Shortly after boxer Jack Johnson (boxer), Jack Johnson was crowned the first black world heavyweight champ in 1908, London pleaded for a "great white hope" to come forward to defeat Johnson, writing: "Jim Jeffries (boxer), Jim Jeffries must now emerge from his Alfalfa farm and remove that golden smile from Jack Johnson's face. Jeff, it's up to you. The White Man must be rescued."

Eugenics

With other modernist writers of the day, London supportedeugenics