John Geary on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John White Geary (December 30, 1819February 8, 1873) was an American lawyer, politician, Freemason, and a

After the war, Geary served two terms as the Republican governor of

After the war, Geary served two terms as the Republican governor of

Pittsburgh ''Tribune-Review'' article

''Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History''

2 vols. Chicago: Standard Publishing, 1912. . * Eicher, John H., and

''Geary and Kansas: Governor Geary's Administration in Kansas with a Complete History of the Territory until July 1857''

Philadelphia: Charles C. Rhodes, 1857. . * Johnson, Samuel A. ''The Battle Cry of Freedom: The New England Emigrant Aid Company in the Kansas Crusade''. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1954. . * Socolofsky, Homer E. ''Kansas Governors''. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1990. . * Tagg, Larry

''The Generals of Gettysburg''

Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. . * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. .

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission description of Geary's governorship

* Th

John W. Geary Letters

at the

Geary Family Papers

including correspondence and John W. Geary's diary, are available for research use at the

William G. Cutler's ''History of the State of Kansas''

*

"John White Geary" Monument at the Historical Marker Database

* John White Geary Papers. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. {{DEFAULTSORT:Geary, John W. 1819 births 1873 deaths People from Mount Pleasant, Pennsylvania American people of Scotch-Irish descent Burials at Harrisburg Cemetery California postmasters Kansas Democrats Pennsylvania Republicans Governors of Kansas Territory Governors of Pennsylvania Republican Party governors of Pennsylvania People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War Union Army generals Mayors of San Francisco Namesakes of San Francisco streets American military personnel of the Mexican–American War Politicians from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Washington & Jefferson College alumni 19th-century American politicians 19th-century Methodists Methodists from California Methodists from Kansas Methodists from Pennsylvania

Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. He was the final alcalde

Alcalde (; ) is the traditional Spanish municipal magistrate, who had both judicial and administrative functions. An ''alcalde'' was, in the absence of a corregidor, the presiding officer of the Castilian '' cabildo'' (the municipal council) a ...

and first mayor of San Francisco

The mayor of the City and County of San Francisco is the head of the executive branch of the San Francisco city and county government. The officeholder has the duty to enforce city laws, and the power to either approve or veto bills passed by t ...

, a governor of the Kansas Territory

The Territory of Kansas was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until January 29, 1861, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Slave and ...

, and the 16th governor of Pennsylvania

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

.

Early years

Geary was born nearMount Pleasant, Pennsylvania

Mount Pleasant is a Borough (Pennsylvania), borough in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, United States. It stands 45 miles (72 km) southeast of Pittsburgh. As of the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census, the borough's population was 4,454 ...

, in Westmoreland County—in what is today the Pittsburgh metropolitan area

Greater Pittsburgh is a populous region centered around its largest city and economic hub, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The region encompasses Pittsburgh's urban core county, Allegheny, and six adjacent Pennsylvania counties: Armstrong, Beaver, ...

. He was the son of Richard Geary, an ironmaster and schoolmaster of Scotch-Irish descent, and Margaret White, a native of Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. Starting at the age of 14, he attended nearby Jefferson College in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania

Canonsburg is a Borough (Pennsylvania), borough in Washington County, Pennsylvania, southwest of Pittsburgh. Canonsburg was laid out by Colonel John Canon in 1789 and incorporated in 1802. The population was 9,735 at the 2020 census. The town li ...

, studying civil engineering and law, but was forced to leave before graduation due to the death of his father, whose debts he assumed. He worked at a variety of jobs, including as a surveyor and land speculator in Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, earning enough to return to college and graduate in 1841. He worked as a construction engineer for the Allegheny Portage Railroad

The Allegheny Portage Railroad was the first railroad constructed through the Allegheny Mountains in central Pennsylvania, United States; it operated from 1834 to 1854 as the first transportation infrastructure through the gaps of the Alleghen ...

. In 1843, he married Margaret Ann Logan, with whom he had several sons, but she died in 1853. Geary then married the widowed Mary Church Henderson in 1858 in Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Carlisle is a Borough (Pennsylvania), borough in and the county seat of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, United States. Carlisle is located within the Cumberland Valley, a highly productive agricultural region. As of the 2020 United States census, ...

.

Geary was active in the state militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

as a teenager. In December 1846, during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

, he was commissioned in the 2nd Pennsylvania Infantry, serving as lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

. He led the regiment heroically at Chapultepec

Chapultepec, more commonly called the "Bosque de Chapultepec" (Chapultepec Forest) in Mexico City, is one of the largest city parks in Mexico, measuring in total just over 686 hectares (1,695 acres). Centered on a rock formation called Chapultep ...

, and was wounded five times in the process. Geary was an excellent target for enemy fire: a huge man for that era, he stood six feet six inches tall, 260 pounds (118 kg) and solidly built. Altogether, he was wounded at least ten times in his military career. Geary's exploits at Belén Gate earned him the rank of colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

and he returned home a war hero.

California politics

Moving west, Geary was appointed postmaster ofSan Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

on January 22, 1849, and on January 8 1850, he was elected the city's alcalde

Alcalde (; ) is the traditional Spanish municipal magistrate, who had both judicial and administrative functions. An ''alcalde'' was, in the absence of a corregidor, the presiding officer of the Castilian '' cabildo'' (the municipal council) a ...

, before California became a state, and then the first mayor of the city. He holds the record as the youngest mayor in San Francisco history. As alcalde, he served as the city's judge in addition to the city's mayor. Geary returned to Pennsylvania in 1852 because of his wife's failing health. After her death, President Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

wanted to appoint him governor of the Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state. ...

, but Geary declined.

Territorial Governor of Kansas

Geary accepted Pierce's appointment as governor of theKansas Territory

The Territory of Kansas was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until January 29, 1861, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Slave and ...

on July 31, 1856. Proslavery forces opposed Geary, favoring instead either acting governor Daniel Woodson

Daniel Woodson (May 24, 1824 – October 5, 1894) was secretary of Kansas Territory (1854–1857) and a five-time acting governor of the territory.

Early life

Woodson was born on a farm in Albemarle County, Virginia and orphaned at age 7. He ...

or Surveyor General John Calhoun (an Illinois politician). Geary spent a month preparing for his new position and then left for the territory. While traveling up the Missouri River, his boat docked at Glasgow, Missouri

Glasgow is a city on the Missouri River mostly in northwest Howard County and extending into the southeast corner of Chariton County in the U.S. state of Missouri. The population was 1,087 at the 2020 census.

The Howard County portion of G ...

, where he happened upon recently fired governor Wilson Shannon

Wilson Shannon (February 24, 1802 – August 30, 1877) was a United States Democratic Party, Democratic politician from Ohio and Kansas. He served as the 14th and 16th governor of Ohio, and was the first Ohio governor born in the state. He was th ...

. They briefly discussed the "Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

" crisis and Geary had previously met with Missouri governor Sterling Price

Major-General Sterling "Old Pap" Price (September 14, 1809 – September 29, 1867) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded infantry in the Western and Trans-Mississippi theaters of the American Civil War. Prior to ...

, who promised Geary that Free-staters would be allowed safe passage through Missouri.

Geary arrived at Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

on September 9 and went to the territorial capital at Lecompton

Lecompton (pronounced ) is a city in Douglas County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 588. Lecompton was the ''de jure'' territorial capital of Kansas from 1855 to 1861, and the Douglas County seat f ...

the following day, becoming the youngest territorial governor of Kansas. He believed that his previous administrative experience in government would help bring peace to the territory, but he was unable to stop the violence. He told his first audience, "I desire to know no party, no section, no North, no South, no East, no West; nothing but Kansas and my country." Geary disbanded the existing Kansas militia, organized a new state militia, and relied heavily on federal troops to help keep order. On October 17, he started a twenty-day tour of the territory and spoke to groups everywhere he stopped to gain their opinions.

Despite his efforts to be a neutral peacemaker, Geary and the proslavery legislature clashed. Geary stopped a large force of Missouri border ruffians who were heading to Lawrence

Lawrence may refer to:

Education Colleges and universities

* Lawrence Technological University, a university in Southfield, Michigan, United States

* Lawrence University, a liberal arts university in Appleton, Wisconsin, United States

Preparator ...

to once again burn the town. Additionally, he vetoed a bill which would provide for an election of delegates to the Lecompton constitutional convention. This bill would have bypassed any referendum on a constitution before being submitted to the U.S. Congress for ratification. The legislature, however, overrode the veto.

Geary also angered Free-staters when he turned away $20,000 from the Vermont

Vermont () is a state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to ...

legislature that was intended to help the suffering from the harsh winter of 1856–57. Geary wrote in his response, "here is

Here is an adverb that means "in, on, or at this place". It may also refer to:

Software

* Here Technologies, a mapping company

* Here WeGo (formerly Here Maps), a mobile app and map website by Here

Television

* Here TV (formerly "here!"), a TV ...

doubtless some suffering ... consequent upon the past disturbances and the present extremely cold weather; but probably no more than exists in other territories or in either of the states of the Union."

Initially, Geary solidly abhorred the proposals he received from Kansas abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

. By the time of the 1856 presidential election, however, he had completely reversed his position and had become intimate friends with Charles Robinson and Samuel Pomeroy

Samuel Clarke Pomeroy (January 3, 1816 – August 27, 1891) was a United States senator from Kansas in the mid-19th century. He served in the United States Senate during the American Civil War. Pomeroy also served in the Massachusetts House of ...

. Additionally, he totally distrusted the proslavery forces and in letters to President Pierce, he blamed them for the deprivations in the territory. Geary even went so far as to reject his candidacy from the Democratic party of Kansas for the U.S. Senate. Instead, he worked with the Free-staters to create a plan for Kansas to be admitted to the Union under the Topeka constitution as a free state, with himself as governor of a Democratic administration. Support for this plan in Congress was lacking.

Geary soon began to fear for his personal safety after his private secretary, Dr. John Gihon, was assaulted by proslavery ruffians. Geary submitted his resignation to incoming President James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

, expecting that he would be reappointed. Instead, Buchanan fired Geary on March 12, 1857, with an effective date of March 20. In his farewell message to the territory, Geary stated that he had not sought the office and "hat it

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

was by no means desirable." He added, "most of the troubles which lately agitated the territory, were occasioned by men who had no especial interest in its welfare... The great body of the actual citizens are conservative, law-abiding and peace-loving men, disposed rather to make sacrifices for conciliation and consequent peace, than to insist for their entire rights should the general body thereby be caused to suffer."

Armed with two guns, Geary left the territory during the night on March 21 and returned to Washington, D.C. Afterward, he spoke at many public meetings about the dangers in Kansas. Although he did not bring peace to the territory, Geary's administration did leave the territory more peaceful than it had been before his arrival. Geary returned to his Pennsylvania farm and remarried.

Civil War

At the start of the Civil War, Geary raised the 147th and28th Pennsylvania Infantry

The 28th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (aka Goldstream Regiment) was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. It was noted for its holding the high ground at the center of the line at Antietam as part of ...

regiments and became colonel of the latter. Commanding the district of the upper Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

, he was wounded and captured near Leesburg, Virginia

Leesburg is a town in the state of Virginia, and the county seat of Loudoun County. Settlement in the area began around 1740, which is named for the Lee family, early leaders of the town and ancestors of Robert E. Lee. Located in the far northea ...

, on March 8, 1862, but was immediately exchanged and returned to duty. On April 25, 1862, he was promoted to Brigadier General, U.S. Volunteers and the command of a brigade in Maj. Gen.

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Nathaniel Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union Army, Union general during the American Civil War, Civil War. A millworker by background, Banks was promine ...

's corps, which he led in the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge- ...

against Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson. His brigade joined Maj. Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia

The Army of Virginia was organized as a major unit of the Union Army and operated briefly and unsuccessfully in 1862 in the American Civil War. It should not be confused with its principal opponent, the Confederate Army of ''Northern'' Virginia ...

in late June. He led it at the Battle of Cedar Mountain

The Battle of Cedar Mountain, also known as Slaughter's Mountain or Cedar Run, took place on August 9, 1862, in Culpeper County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. Union forces under Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks attacked Confederate ...

on August 9, 1862, where he was seriously wounded in the arm and leg. He returned to duty on October 15 as the division commander; the corps was now part of the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

, designated the XII Corps 12th Corps, Twelfth Corps, or XII Corps may refer to:

* 12th Army Corps (France)

* XII Corps (Grande Armée), a corps of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* XII (1st Royal Saxon) Corps, a unit of the Imperial German Army

* XII ...

, under the command of Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum.

Geary's division was heavily engaged at Chancellorsville, where he was knocked unconscious as a cannonball shot past his head on May 3, 1863. (Some accounts state that he was hit in the chest with a cannonball.)

At the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

, Slocum's corps arrived after the first day's (July 1, 1863) fighting subsided and took up a defensive position on Culp's Hill

Culp's Hill,. The modern U.S. Geographic Names System refers to "Culps Hill". which is about south of the center of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, played a prominent role in the Battle of Gettysburg. It consists of two rounded peaks, separated by a ...

, the extreme right of the Union line. On the second day, heavy fighting on the Union left demanded reinforcements and Geary was ordered to leave a single brigade, under Brig. Gen.

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

George S. Greene, on Culp's Hill and follow another division, which was just departing. Geary lost track of the division he was supposed to follow south on the Baltimore Pike and inexplicably marched completely off the battlefield, eventually reaching Rock Creek. His two brigades finally returned to Culp's Hill by 9:00 pm that night, arriving in the midst of a fierce fire fight between a Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

division and Greene's lone brigade. This embarrassing incident might have damaged his reputation except for two factors: the part of the battle he was supposed to march to join had ended, so he wasn't really needed; and, because of a dispute between army commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. H ...

and Slocum over the filing of their official reports, little public notice ensued.

The XII Corps was transferred west to join the besieged Union army at Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

. Geary's son Edward died in his arms at the Battle of Wauhatchie

The Battle of Wauhatchie was fought October 28–29, 1863, in Hamilton and Marion counties, Tennessee, and Dade County, Georgia, in the American Civil War. A Union force had seized Brown's Ferry on the Tennessee River, opening a supply line ...

, enraging him sufficiently to prevail in a battle in which his division was greatly outnumbered. He distinguished himself in command during the Battle of Lookout Mountain

The Battle of Lookout Mountain also known as the Battle Above The Clouds was fought November 24, 1863, as part of the Chattanooga Campaign of the American Civil War. Union forces under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker assaulted Lookout Mountain, Chattan ...

, the entire Atlanta Campaign, Sherman's March to the Sea

Sherman's March to the Sea (also known as the Savannah campaign or simply Sherman's March) was a military campaign of the American Civil War conducted through Georgia from November 15 until December 21, 1864, by William Tecumseh Sherman, major ...

, and the Carolinas Campaign

The campaign of the Carolinas (January 1 – April 26, 1865), also known as the Carolinas campaign, was the final campaign conducted by the United States Army (Union Army) against the Confederate States Army in the Western Theater. On January 1 ...

. He oversaw the surrender of Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

, and briefly served as the city's military governor, where he was breveted to major general.

Governor of Pennsylvania and death

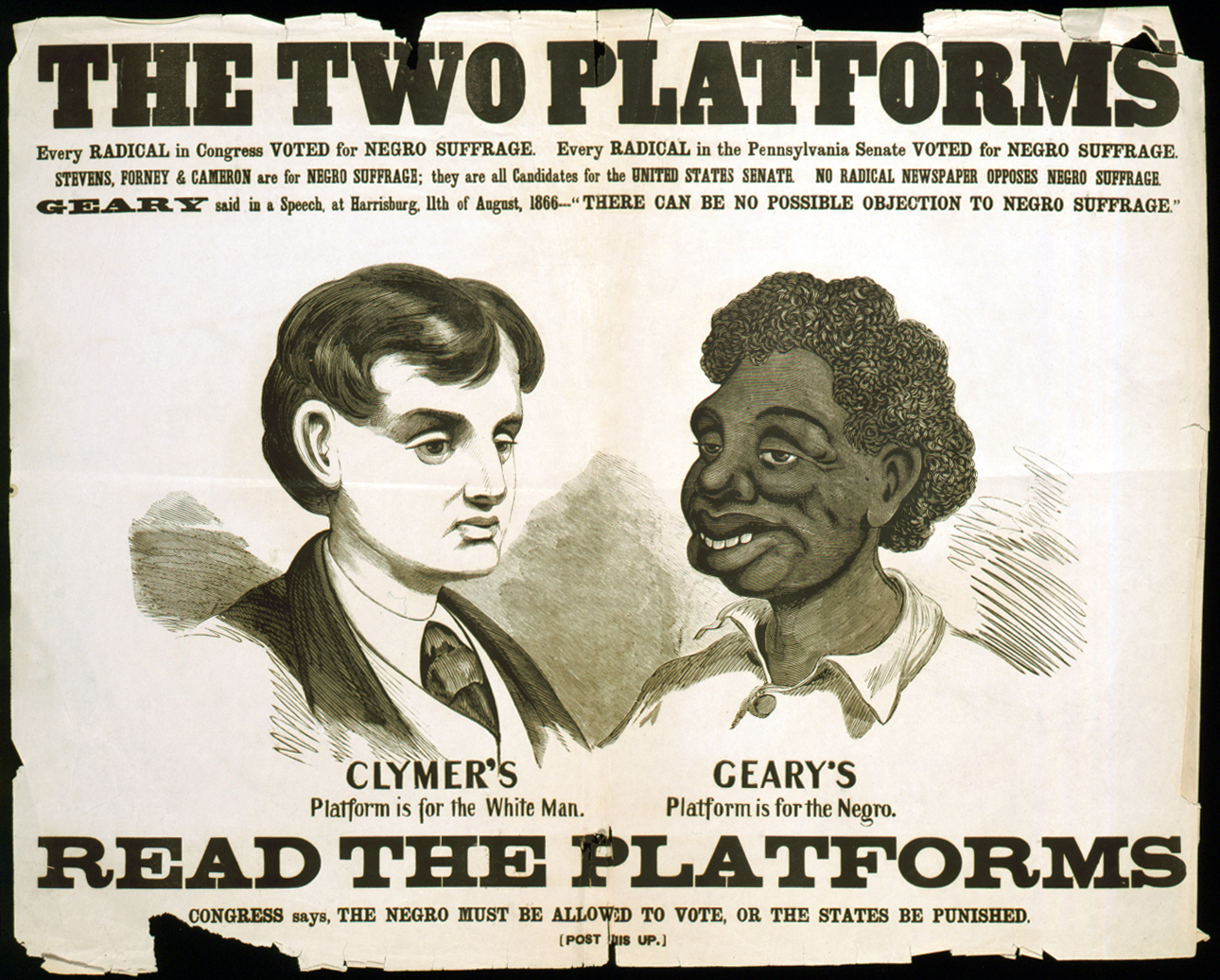

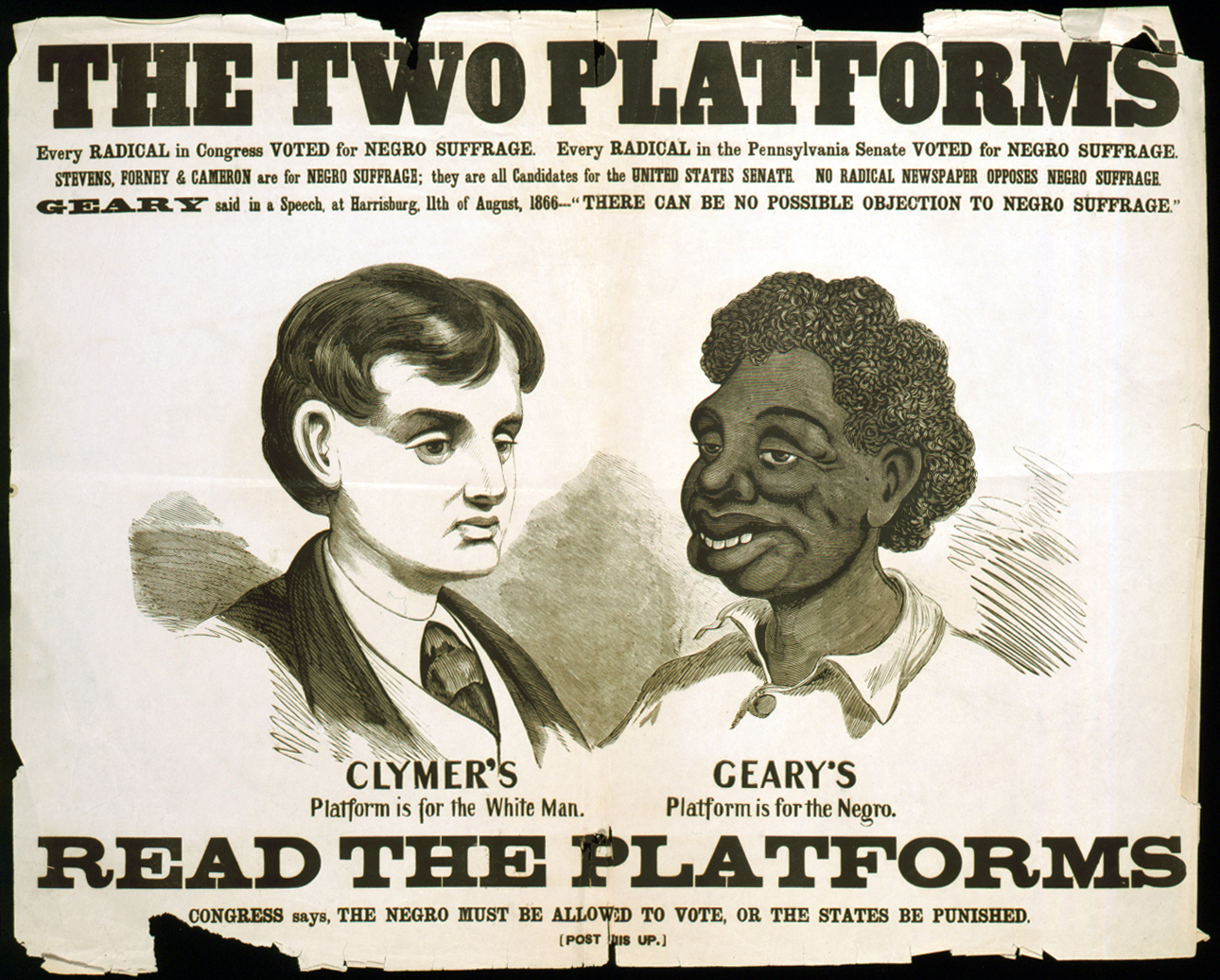

After the war, Geary served two terms as the Republican governor of

After the war, Geary served two terms as the Republican governor of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, from 1867 to 1873. He established a reputation as a political independent, attacking the political influence of the railroads and vetoing many special interest bills.

On February 8, 1873, less than three weeks after leaving the governor's post, Geary was fatally stricken with a heart attack while preparing breakfast for his infant son in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the 9th largest city and 15th largest municipality in Pe ...

. He was 53 years old. He was buried in Harrisburg with state honors in Mount Kalmia Cemetery, now, the Harrisburg Cemetery.

Freemasonry

Geary was made a Mason at Sight on January 4, 1847, in Pennsylvania (Philanthropy Lodge #255), just before he left with his troops to fight in the Mexican War. During the Civil War, he was the commanding Union general at the fall ofSavannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

. He placed Federal troops about the quarters of Solomon's Lodge No. 1 to save it from looting and damage. Later, while Geary was governor of Pennsylvania, the Lodge sent him a resolution of thanks. He answered by claiming it was the principles and tenets of Freemasonry that helped Reconstruction to be as successful as it finally turned out to be. In this reply, he said: "... I feel again justified in referring to our beloved institution, by saying that to Freemasonry the people of the country are indebted for many mitigations of the suffering caused by the direful passions of war."

In memoriam

Geary County, Kansas

Geary County (county code GE) is a county located in the U.S. state of Kansas. As of the 2020 census, the county population was 36,739. Its county seat and most populous city is Junction City. The county is named in honor of Governor John W. ...

, was renamed in honor of John W. Geary in 1889 (previously named Davis County for Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

, it was renamed at the insistence of its citizens; in 1893, the county electorate rejected an attempt to restore the Davis County name), as is Geary Boulevard

Geary Boulevard (designated as Geary Street east of Van Ness Avenue) is a major east–west thoroughfare in San Francisco, California, United States, beginning downtown at Market Street near Market Street's intersection with Kearny Street, and ...

in San Francisco, a major artery in that city, Geary Avenue on the field at Gettysburg, Geary Street in New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

New Cumberland is a borough (Pennsylvania), borough in easternmost Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, United States. New Cumberland was incorporated on March 21, 1831. The population was 7,277 at the 2010 census. The ...

(where Geary owned a home), Geary Street in Harrisburg, the capital of Pennsylvania, and Geary Hall, an undergraduate dorm building in East Halls at Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University (Penn State or PSU) is a Public university, public Commonwealth System of Higher Education, state-related Land-grant university, land-grant research university with campuses and facilities throughout Pennsylvan ...

. There is a monument to Geary in the town center of Mount Pleasant, Pennsylvania

Mount Pleasant is a Borough (Pennsylvania), borough in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, United States. It stands 45 miles (72 km) southeast of Pittsburgh. As of the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census, the borough's population was 4,454 ...

. Geary, Kansas

Geary is a ghost town in Doniphan County, Kansas

Doniphan County (county code DP) is a county located in the U.S. state of Kansas. As of the 2020 census, the county population was 7,510. Its county seat is Troy, and its most populous city is ...

(in Doniphan County) was also named in his honor, but the town ceased to exist in 1905. In 1914, a monument to Geary was erected on Culp's Hill at Gettysburg, but it was not formally dedicated until August 11, 2007.See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-ranke ...

Notes

References

* Blackmar, Frank W''Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History''

2 vols. Chicago: Standard Publishing, 1912. . * Eicher, John H., and

David J. Eicher

David John Eicher (born August 7, 1961) is an American editor, writer, and popularizer of astronomy and space. He has been editor-in-chief of ''Astronomy'' magazine since 2002. He is author, coauthor, or editor of 23 books on science and American ...

. ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. .

* Geary, John W. ''A Politician Goes to War: The Civil War Letters of John White Geary''. Edited by William Alan Blair. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995. .

* Gihon, John H''Geary and Kansas: Governor Geary's Administration in Kansas with a Complete History of the Territory until July 1857''

Philadelphia: Charles C. Rhodes, 1857. . * Johnson, Samuel A. ''The Battle Cry of Freedom: The New England Emigrant Aid Company in the Kansas Crusade''. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1954. . * Socolofsky, Homer E. ''Kansas Governors''. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1990. . * Tagg, Larry

''The Generals of Gettysburg''

Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. . * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. .

External links

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission description of Geary's governorship

* Th

John W. Geary Letters

at the

Georgia Historical Society

The Georgia Historical Society (GHS) is a statewide historical society in Georgia. Headquartered in Savannah, Georgia, GHS is one of the oldest historical organizations in the United States. Since 1839, the society has collected, examined, and tau ...

.

* ThGeary Family Papers

including correspondence and John W. Geary's diary, are available for research use at the

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania is a long-established research facility, based in Philadelphia. It is a repository for millions of historic items ranging across rare books, scholarly monographs, family chronicles, maps, press reports and v ...

.

William G. Cutler's ''History of the State of Kansas''

*

"John White Geary" Monument at the Historical Marker Database

* John White Geary Papers. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. {{DEFAULTSORT:Geary, John W. 1819 births 1873 deaths People from Mount Pleasant, Pennsylvania American people of Scotch-Irish descent Burials at Harrisburg Cemetery California postmasters Kansas Democrats Pennsylvania Republicans Governors of Kansas Territory Governors of Pennsylvania Republican Party governors of Pennsylvania People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War Union Army generals Mayors of San Francisco Namesakes of San Francisco streets American military personnel of the Mexican–American War Politicians from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Washington & Jefferson College alumni 19th-century American politicians 19th-century Methodists Methodists from California Methodists from Kansas Methodists from Pennsylvania