John Ferdinand Smyth Stuart on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

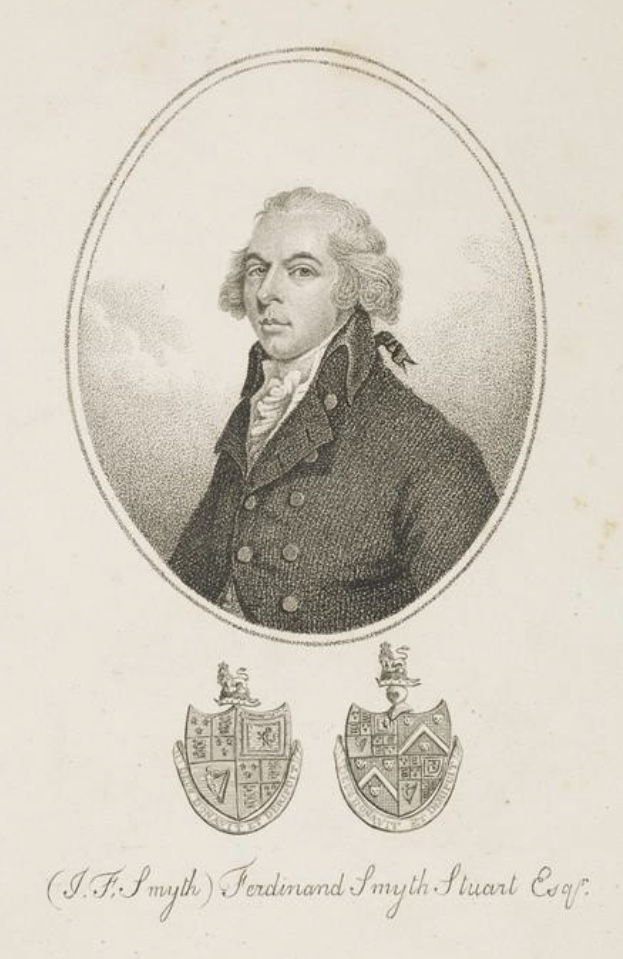

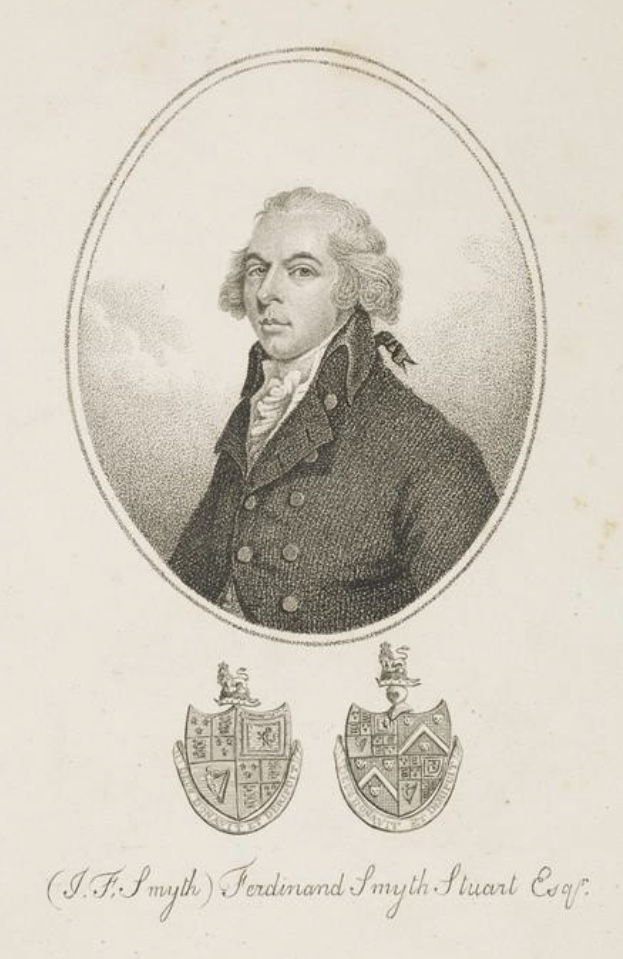

John Ferdinand Smyth Stuart (1745 – 20 December 1814), known until 1793 as John Ferdinand Smyth and mostly after that as Ferdinand Smyth Stuart, was a Scottish-born American

John Ferdinand Smyth Stuart (1745 – 20 December 1814), known until 1793 as John Ferdinand Smyth and mostly after that as Ferdinand Smyth Stuart, was a Scottish-born American

pp. 36–41

/ref> Stuart stated in 1808 that he had been named for his godfather,

John Ferdinand Smyth: loyalist and liar

at anthonyjcamp.com, as published in ''Genealogists' Magazine'', vol. 31, no. 11 (September 2015) Stuart recalled being orphaned by the death of his mother when he was two and his father when he was five, his father being drowned in a river, after falling off a bridge during an attempt to arrest him. According to Stuart, he was “bred to Physic and was at one of the Scotch Universities” and migrated to Virginia in the year 1763. An obituary said that Stuart had been a Doctor of Medicine and had been educated “amid the Grampian hills”, and then had “attended the lectures of Dr Gregory” at Aberdeen, but no university career has been traced.

at hofstra.edu (Special Collections Department, Long Island Studies Institute), pp. 4, 5, 10, 32: ”Upon her father’s return to America seventeen years later, a relationship developed with him and his children from his second wife Eunice Grey (c1776-1818). This union created seven half brothers and sisters. They were Henry Stuart Smyth Stuart (1793-1794), Henrietta Maria Stuart Smyth Stuart (1797-1813), Mary Clementina Stuart Smyth Stuart (c1799-1826), Charles Henry Stuart Smyth Stuart (1802-1802), Constantine Wentworth Stuart Smyth Stuart (1805-1849), Spencer Percival Stuart Smyth Stuart (1807-c1807), and Ferdinand Stuart Smyth Stuart (c1812-1835).” Before his return to New York in 1797, Stuart had begun a second family in England with Eunice Gray, a girl of about sixteen. Their son Henry was born in 1793, their first daughter, Henrietta Maria, in 1797, and another daughter, Mary Clementina, about 1799, then another son, Charles Henry, in 1802. On 7 September 1803, Stuart married Eunice Gray, at

Stuart, John Ferdinand Smyth 1745–1814

at

John Ferdinand Smyth Stuart

Online Books at upenn.edu

''Narrative or Journal of Capt. John Ferdinand Dalziel Smyth, of the Queen's Rangers'' (1778)

reprinted in ''The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography'', Vol. 39, No. 2 (1915), in open

“Memoirs of FERDINAND SMYTH STUART, M.D., Major in the British Army, and Grandson of the Duke of Monmouth”

in ''The Monthly Magazine'', 1 February 1815, pp. 36–41

by

John Ferdinand Smyth Stuart (1745 – 20 December 1814), known until 1793 as John Ferdinand Smyth and mostly after that as Ferdinand Smyth Stuart, was a Scottish-born American

John Ferdinand Smyth Stuart (1745 – 20 December 1814), known until 1793 as John Ferdinand Smyth and mostly after that as Ferdinand Smyth Stuart, was a Scottish-born American loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

and physician who claimed to be a great-grandson of King Charles II. As the author of ''A Tour in the United States of America'' (1784), he used the name John Ferdinand Dalziel Smyth.

Leaving America during the Revolutionary War, Stuart spent the rest of his life in England and the West Indies.

Background and early life

Stuart was born in Scotland in 1745 and began life there as John Smyth or John Ferdinand Smyth. He later wrote that he was the son of R. Wentworth Smyth, a gentleman who had fought in theJacobite rising of 1715

The Jacobite rising of 1715 ( gd, Bliadhna Sheumais ;

or 'the Fifteen') was the attempt by James Edward Stuart (the Old Pretender) to regain the thrones of England, Ireland and Scotland for the exiled Stuarts

The House of Stuart, ori ...

and also the later one of 1745. According to Stuart's account, in 1744 his elderly father married Maria Julia Dalziel, a widow of fifteen, as his second wife. He reported that his mother was a granddaughter of General James Crofts, a natural son of the Duke of Monmouth

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranked ...

, who was a son of Charles II, and that Wentworth Smyth was Monmouth's son by Henrietta Maria Wentworth, a daughter of Thomas, Lord Wentworth, and granddaughter of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Cleveland

Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Cleveland (159125 March 1667), was an English landowner and Royalist general during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, described by one historian as a "much under-rated field commander". A distant relative of Thomas We ...

. Henrietta Maria had died in 1686, not long after Monmouth's execution, and Stuart said a Colonel Smyth, an aide-de-camp of Monmouth's, had adopted her son and made him his own heir.Edward Irving Carlyle

Edward Irving Carlyle (15 September 1871 – 9 February 1952) was a British author and historian.

He was educated at St John's College, Oxford, where he was a Casberd scholar. He graduated in 1894 and was appointed assistant editor of the ''Dic ...

, “Stuart, John Ferdinand Smyth”, in ''Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

1885-1900'', Vol. 55 Consequently, Stuart's father had grown up in France, from where he returned to Scotland at the time of the 1715 Rising.“Memoirs of FERDINAND SMYTH STUART, M.D., Major in the British Army, and Grandson of the Duke of Monmouth”, in ''The Monthly Magazine'', 1 February 1815pp. 36–41

/ref> Stuart stated in 1808 that he had been named for his godfather,

Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. The ...

.

The historian Allan Fea

Allan Fea (25 May 1860 – 9 June 1956), was a British historian, specializing in the English Civil Wars period and the House of Stuart, and an antiquary, after a first career as a clerk at the Bank of England.

Life

Fea was born at St Pancras, Lon ...

states in his biography of Monmouth that Major-General James Crofts married a daughter of Sir Thomas Taylor (“after 1706, when he is described as single”) and had a daughter, Maria Julia; and that she married first a Mr Dalziel and secondly R. Wentworth Smyth-Stuart, who claimed to be Monmouth's son by Henrietta Maria Wentworth. Fea was convinced that Monmouth ”undoubtedly left a son by her (born in 1681), who was adopted and educated in Paris by Colonel Smyth”. A genealogist, Anthony J. Camp

Anthony John Camp (born November 1937) is a British genealogist and former director of the Society of Genealogists.

Early life and education

Camp was born at Walkern, near Stevenage, Hertfordshire. His father was an agricultural carpenter and ...

, has cast doubts on this account.Anthony J. Camp

Anthony John Camp (born November 1937) is a British genealogist and former director of the Society of Genealogists.

Early life and education

Camp was born at Walkern, near Stevenage, Hertfordshire. His father was an agricultural carpenter and ...

John Ferdinand Smyth: loyalist and liar

at anthonyjcamp.com, as published in ''Genealogists' Magazine'', vol. 31, no. 11 (September 2015) Stuart recalled being orphaned by the death of his mother when he was two and his father when he was five, his father being drowned in a river, after falling off a bridge during an attempt to arrest him. According to Stuart, he was “bred to Physic and was at one of the Scotch Universities” and migrated to Virginia in the year 1763. An obituary said that Stuart had been a Doctor of Medicine and had been educated “amid the Grampian hills”, and then had “attended the lectures of Dr Gregory” at Aberdeen, but no university career has been traced.

Life in America

Stuart emigrated to theThirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

and settled near Williamsburg in the Colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colonial empire, English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertG ...

, where he later practised as a physician. By the 1770s, he had become a planter, renting plantations rather than owning them. The American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

broke out, and on 15 October 1775, Smyth joined the Loyalist forces. He later wrote that at one time he commanded an armed sloop in Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

and at another raised a company of men for frontier work. More than once he was taken prisoner, and was shackled for eighteen months.

Escaping from rebel forces, Stuart arrived in New York in 1777, and was commissioned as a Captain into the Queen's Rangers

The Queen's Rangers, also known as the Queen's American Rangers, and later Simcoe's Rangers, were a Loyalist military unit of the American Revolutionary War. Formed in 1776, they were named for Queen Charlotte, consort of George III. The Queen' ...

, a Loyalist regiment. In October 1777, he fought at the Battle of Germantown

The Battle of Germantown was a major engagement in the Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolutionary War. It was fought on October 4, 1777, at Germantown, Pennsylvania, between the British Army led by Sir William Howe, and the American Con ...

. Back in New York, at about the end of 1777, Stuart wrote his ''Narrative or Journal of Capt. John Ferdinand Dalziel Smyth, of the Queen's Rangers'', setting out his adventures, and was critical of the “deluded and mistaken” rebels. This was printed in 1778. The Queen's Rangers were stationed at King's Bridge, New York, from July 1778, and on 23 October 1778, Stuart married Abigail Haugewout, the daughter of a loyalist farmer in Hempstead, Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United Sta ...

. Their daughter Elizabeth was born in 1780.

Stuart had leave to be absent from two musters in 1778, one in August and another in October, but he was on duty in February 1779. In May 1779, he launched a number of proceedings against his commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel John Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe (25 February 1752 – 26 October 1806) was a British Army general and the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1791 until 1796 in southern Ontario and the Drainage basin, watersheds of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior. ...

, but they were found to be “Malicious, Frivolous, Vexatious, & Groundless”. Simcoe claimed that Captain Smyth “avoided military service whenever possible”. At a muster in June 1779, he had sick leave, and not far into 1780, he returned to England, on the grounds of ill health.

England and West Indies

Stuart remained an officer on half-pay for the duration of the American War. The British government had set up a Commission to give financial help to loyalists with losses from the war, and in 1780 they awarded Stuart £100 a year as an interim allowance, increasing this to £200 in 1781 and to £300 in 1783. He made an application to the Privy Council, asking to be awardedLong Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United Sta ...

, a Crown property in the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

, in view of his claimed losses of 3,300 acres in Virginia and Maryland, but he was not believed and this was rejected. His half-pay came to an end in 1783.

In 1784, allegations were made against Stuart to the claims commissioners, and his allowance was suspended. Stuart then wrote his book ''A Tour in the United States of America'', which was published by George Robinson in 1784, agreeing to pay £160 for the printing. This, however, brought his account of himself to a wide public, and people who had known him in North America challenged it.

In 1785, Stuart went out to Jamaica, where he was appointed a Major “in that Island only”, but only remained there for sixteen days, as the result of a hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depend ...

.

In 1793, Captain Smyth adopted the name of Stuart, to mark his claim to descent from the House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter fi ...

. He later explained this in letters to the Earl of Moira

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

, commenting "for, indeed, what was the name of Smyth to me?"

In 1795, Stuart accepted a post as assistant barrack-master-general in San Domingo

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and t ...

and to get there joined Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Sir Hugh Cloberry Christian on an expedition to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

. He was shipwrecked three times in 1795 and 1796 and was present at the British capture of Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Amerindian ...

and Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

. In San Domingo, although not employed as a medical officer, he prescribed five grains of tartarised antimony and a tablespoonful of soft sugar for the treatment of yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

, later claiming that this had proved a good treatment. On his return to England, Stuart continued to pursue his financial claims unsuccessfully, but writing many times in support of them.

In 1803, while Stuart was barrack-master at Billericay

Billericay ( ) is a town and civil parish in the Borough of Basildon, Essex, England. It lies within the London Basin and constitutes a commuter town east of Central London. The town has three secondary schools and a variety of open spaces. It is ...

, he suffered a severe beating which knocked out several of his teeth. In the final years of his life, he was barrack-master at Landguard Fort

Landguard Fort is a fort at the mouth of the River Orwell outside Felixstowe, Suffolk, designed to guard the mouth of the river. It is now managed by the charity English Heritage and is open to the public.

History

Originally known as Langer ...

, near Felixstowe

Felixstowe ( ) is a port town in Suffolk, England. The estimated population in 2017 was 24,521. The Port of Felixstowe is the largest container port in the United Kingdom. Felixstowe is approximately 116km (72 miles) northeast of London.

His ...

in Suffolk.

In a book of 1808, shortly after the death of Cardinal Stuart, Stuart described himself as the nearest descendant of the House of Stuart. In 1814, he retired from his work as a barrack-master and settled in Vernon Place, Bloomsbury Square

Bloomsbury Square is a garden square in Bloomsbury, in the London Borough of Camden, London. Developed in the late 17th century, it was initially known as Southampton Square and was one of the earliest London squares. By the early 19th century, Be ...

.

Marriages and children

On 23 October 1778, while he was Captain Smyth of theQueen's Rangers

The Queen's Rangers, also known as the Queen's American Rangers, and later Simcoe's Rangers, were a Loyalist military unit of the American Revolutionary War. Formed in 1776, they were named for Queen Charlotte, consort of George III. The Queen' ...

, against her father's wishes Stuart married Abigail Haugewout, the 23-year-old daughter of Leffert Haugewout, a loyalist farmer of Hempstead, New York

The Town of Hempstead (also known historically as South Hempstead) is the largest of the three Administrative divisions of New York#Town, towns in Nassau County, New York, Nassau County (alongside North Hempstead, New York, North Hempstead and Oys ...

. They set up house in Oyster Bay and had one daughter, Elizabeth, born in October 1780, but by then Smyth had gone to live in England. His pregnant wife did not go with him and lived on until 1828, on a farm of fifteen acres in Hempstead which her father gave her. In 1797, Stuart returned on a visit and met his wife in New York. In 1802, his daughter Elizabeth married Gideon Nichols, a Hempstead merchant.Hart Nichols Collection, 1730-1930at hofstra.edu (Special Collections Department, Long Island Studies Institute), pp. 4, 5, 10, 32: ”Upon her father’s return to America seventeen years later, a relationship developed with him and his children from his second wife Eunice Grey (c1776-1818). This union created seven half brothers and sisters. They were Henry Stuart Smyth Stuart (1793-1794), Henrietta Maria Stuart Smyth Stuart (1797-1813), Mary Clementina Stuart Smyth Stuart (c1799-1826), Charles Henry Stuart Smyth Stuart (1802-1802), Constantine Wentworth Stuart Smyth Stuart (1805-1849), Spencer Percival Stuart Smyth Stuart (1807-c1807), and Ferdinand Stuart Smyth Stuart (c1812-1835).” Before his return to New York in 1797, Stuart had begun a second family in England with Eunice Gray, a girl of about sixteen. Their son Henry was born in 1793, their first daughter, Henrietta Maria, in 1797, and another daughter, Mary Clementina, about 1799, then another son, Charles Henry, in 1802. On 7 September 1803, Stuart married Eunice Gray, at

St Martin-in-the-Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. It is dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. There has been a church on the site since at least the mediev ...

, Westminster. Their third son, Constantine Wentworth, was born in August 1805, a fourth, Spencer Percival, in 1807, and a fifth and last son, Ferdinand, in 1812. As a result of Stuart's visit to New York in 1797, his daughter Elizabeth at Hempstead was in contact with her new relations in England. Four of the children in England died young: Henry in 1794, Charles Henry in 1802, Spencer Percival about 1807, and Henrietta Maria in 1813, just after her 16th birthday.

Death and posterity

On 20 December 1814, Stuart died as a result of being run over by a carriage which hit him at the corner ofSouthampton Street

Southampton Street is a street in central London, running north from the Strand to Covent Garden Market.

There are restaurants in the street such as Bistro 1

and Wagamama. There are also shops

such as The North Face outdoor clothing shop. ...

, Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

, leaving his second family destitute. He was buried on 1 January 1815 at Marylebone

Marylebone (usually , also , ) is a district in the West End of London, in the City of Westminster. Oxford Street, Europe's busiest shopping street, forms its southern boundary.

An Civil parish#Ancient parishes, ancient parish and latterly a ...

, where the parish register notes that he was of St George's parish, Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural, intellectual, and educational institutions.

Bloomsbury is home of the British Museum, the largest mus ...

. The Monthly Magazine

''The Monthly Magazine'' (1796–1843) of London began publication in February 1796.

Contributors

Richard Phillips was the publisher and a contributor on political issues. The editor for the first ten years was a literary jack-of-all-trades, Dr ...

printed a six-page obituary which celebrated Stuart's life, believing his version of all events, and appealed on behalf of his dependants:

In January 1815, Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865) was a British statesman who was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century. Palmerston dominated British foreign policy during the period ...

, Secretary for War, agreed to Eunice Stuart being paid an annual allowance of £25 out of his Compassionate Fund, including £15 for the support of her children. In June 1816, the Prince Regent

A prince regent or princess regent is a prince or princess who, due to their position in the line of succession, rules a monarchy as regent in the stead of a monarch regnant, e.g., as a result of the sovereign's incapacity (minority or illness ...

, the future George IV, granted Eunice a pension of £50 a year from the Civil List

A civil list is a list of individuals to whom money is paid by the government, typically for service to the state or as honorary pensions. It is a term especially associated with the United Kingdom and its former colonies of Canada, India, New Zeal ...

, to supplement the grant from the Compassionate Fund, which she reported to Palmerston. She died in 1818, and Palmerston increased the money paid for the children to £24 a year. A neighbour paid for Constantine Wentworth's education at Charterhouse School

(God having given, I gave)

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public school Independent day and boarding school

, religion = Church of England

, president ...

, Smithfield, and had some correspondence with Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy' ...

, telling him the Prince had asked the College of Arms

The College of Arms, or Heralds' College, is a royal corporation consisting of professional Officer of Arms, officers of arms, with jurisdiction over England, Wales, Northern Ireland and some Commonwealth realms. The heralds are appointed by the ...

to look into the children's origins and that the £50 pension had been recommended by Sir Isaac Heard. Scott himself sent £5 for the children.

Two of Stuart's remaining children died in their twenties, Mary Clementina in 1826, and Ferdinand in 1835. Constantine Wentworth lived until 1849, and married. In July 1828, he was an officer in the 6th Regiment of Foot and was promoted from Ensign to Lieutenant without purchase. He resigned his commission at Poona, in 1832, and later visited his half-sister, Elizabeth, in Hempstead, New York. She had a number of children and grandchildren, lived until 1858, and left many descendants.

Published works

*John Ferdinand Dalziel Smyth, ''Narrative or Journal of Capt. John Ferdinand Dalziel Smyth, of the Queen's Rangers'' (New York, 1778), is Stuart's first known substantial publication. *John Ferdinand Dalziel Smyth, ''A Tour in the United States of America'' (London, G. Robinson, 1784), a much longer work, describes Stuart's recent travels there and his activities during the War of Independence. The book was republished in 2010 in a 468-page paperback byKessinger Publishing

Kessinger Publishing LLC is an American print-on-demand

Print on demand (POD) is a printing technology and business process in which book copies (or other documents, packaging or materials) are not printed until the company receives an orde ...

of Whitefish, Montana

Whitefish (Salish: epɫx̣ʷy̓u, "has whitefish") is a town in Flathead County, Montana, United States. According to the 2020 United States Census, there were 7,751 people in the town.

History

Long before the first Europeans came to Whitefish, ...

, . It was translated into French and in 1791 published by Buisson of Paris under the title ''Voyage dans les États-Unis de l'Amérique, fait en 1784''. Stuart's view of the country has been called

* John Ferdinand Smyth Stuart, ''A Letter to Lord Henry Petty on Coercive Vaccination'' (London, 1807) is a forceful medical and political argument against vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

addressed to Lord Henry Petty, the youthful Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

.Chambers, Book of Days, vol. I, p. 628 It was motivated by the death of one of his own children.

*Ferdinand Smyth Stuart, ''The Case of Ferdinand Smyth Stuart'' (London, 1807) returned to Stuart's complaints about his treatment by the British government.

*Ferdinand Smyth Stuart, ''Destiny and Fortitude: An Historical Poem: In Sixteen Elegies: Being a Detail of the Misfortunes of the Illustrious House of Stuart, by Ferdinand Smyth Stuart, the nearest descendant'' (London: Printed for the Author, by Cox, Son, and Baylis, 1808): this followed shortly after the death of Henry Benedict Stuart

Henry Benedict Thomas Edward Maria Clement Francis Xavier Stuart, Cardinal Duke of York (6 March 1725 – 13 July 1807) was a Roman Catholic cardinal, as well as the fourth and final Jacobite heir to publicly claim the thrones of Great Brit ...

, the last legitimate Stuart descendant of King James II

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was deposed in the Glorious Re ...

, and explained his own connection to the royal house.

Notes

External links

Stuart, John Ferdinand Smyth 1745–1814

at

WorldCat

WorldCat is a union catalog that itemizes the collections of tens of thousands of institutions (mostly libraries), in many countries, that are current or past members of the OCLC global cooperative. It is operated by OCLC, Inc. Many of the OCL ...

John Ferdinand Smyth Stuart

Online Books at upenn.edu

''Narrative or Journal of Capt. John Ferdinand Dalziel Smyth, of the Queen's Rangers'' (1778)

reprinted in ''The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography'', Vol. 39, No. 2 (1915), in open

JSTOR

JSTOR (; short for ''Journal Storage'') is a digital library founded in 1995 in New York City. Originally containing digitized back issues of academic journals, it now encompasses books and other primary sources as well as current issues of j ...

collections“Memoirs of FERDINAND SMYTH STUART, M.D., Major in the British Army, and Grandson of the Duke of Monmouth”

in ''The Monthly Magazine'', 1 February 1815, pp. 36–41

by

Anthony J. Camp

Anthony John Camp (born November 1937) is a British genealogist and former director of the Society of Genealogists.

Early life and education

Camp was born at Walkern, near Stevenage, Hertfordshire. His father was an agricultural carpenter and ...

, at anthonyjcamp.com, as published in ''Genealogists' Magazine'', vol. 31, no. 11 (September 2015)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stuart, John Ferdinand Smyth

1745 births

1814 deaths

18th-century Scottish medical doctors

Loyalist military personnel of the American Revolutionary War

House of Stuart