John Doubleday (restorer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Doubleday (about 1798 – 25January 1856) was a British craftsperson, restorer, and dealer in antiquities who was employed by the

From 1836 to 1856 Doubleday worked in the Department of Antiquities at the

From 1836 to 1856 Doubleday worked in the Department of Antiquities at the

Beyond his work on the Portland Vase, several other of Doubleday's responsibilities at the British Museum have been recorded. In 1851 he successfully undid damaging restoration work by

Beyond his work on the Portland Vase, several other of Doubleday's responsibilities at the British Museum have been recorded. In 1851 he successfully undid damaging restoration work by

Little is known about Doubleday's personal life, and nothing about his upbringing or education. An 1859 edition of '' The English Cyclopædia'' described him as American, and the

Little is known about Doubleday's personal life, and nothing about his upbringing or education. An 1859 edition of '' The English Cyclopædia'' described him as American, and the

British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

for the last 20 years of his life. He undertook several duties for the museum, not least as a witness in criminal trials, but was primarily their specialist restorer, perhaps the first person to hold the position. He is best known for his 1845 restoration of the severely-damaged Roman Portland Vase

The Portland Vase is a Roman cameo glass vase, which is dated to between AD 1 and AD 25, though low BC dates have some scholarly support. It is the best known piece of Roman cameo glass and has served as an inspiration to many glass and porcelain ...

, an accomplishment that places him at the forefront of his profession at the time.

While at the British Museum, Doubleday also dealt in copies of coins, medals, and ancient seals. His casts in coloured sulphur and in white metal

The white metals are a series of often decorative bright metal alloys used as a base for plated silverware, ornaments or novelties, as well as any of several lead-based or tin-based alloys used for things like bearings, jewellery, miniature f ...

of works in both national and private collections, allowed smaller collections to hold copies at a fraction of the price that the originals would command. Thousands of his copies entered the collections of institutions and individuals. Yet the accuracy he achieved led to confusion with the originals; after his death he was labelled a forger, but with the caveat that " ether he did copies with the intention of deceiving collectors or not is open to doubt".

Little is known about Doubleday's upbringing or personal life. Several sources describe him as an American, including the 1851 United Kingdom census

The United Kingdom Census of 1851 recorded the people residing in every household on the night of Sunday 30 March 1851, and was the second of the Census in the United Kingdom, UK censuses to include details of household members. However, this censu ...

, which records him as a New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

-born British subject. An obituary noted that he worked at a printer's shop for more than 20 years during his youth, which gave him the experience of casting type that he would employ in his later career as a copyist. Doubleday's early life, family, and education are otherwise unknown. He died in 1856, leaving a wife and five daughters, all English; the eldest child was born around 1833.

At the British Museum

From 1836 to 1856 Doubleday worked in the Department of Antiquities at the

From 1836 to 1856 Doubleday worked in the Department of Antiquities at the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

. He appears to have been employed as a freelancer who also occasionally acted as an agent in sales to the museum. At times he presented the museum with items including coins, medals, and Egyptian objects. Among other donations, his 1830 gift of 2,433 casts of medieval seals was the only significant donation recorded by the museum that year, he offered several coins and another 750 casts the following year, and in 1836, he presented the museum with a Henry Corbould

Henry Corbould (1787–1844) was an English artist.

Life

The third son of Richard Corbould, he was born in London. He studied painting with his father, and was at an early age admitted as a student of the Royal Academy, under Fuseli, where he ...

lithograph of himself. A further presentation in 1837 was still considered, in 1996, to be one of the museum's most important collections of casts of seals. He seems to have been the museum's primary, and perhaps its first, dedicated restorer; his death was described as leaving the post vacant. At his death, it was noted that he was "chiefly employed in the reparation of innumerable works of art, which could not have been intrusted to more skilful or more patient hands", and that he "was well known as one of the most valuable servants of that department".

Portland Vase

The highlight of Doubleday's career came after 7 February 1845 when a young man, who later admitted having spent the prior week "indulging in intemperance", smashed thePortland Vase

The Portland Vase is a Roman cameo glass vase, which is dated to between AD 1 and AD 25, though low BC dates have some scholarly support. It is the best known piece of Roman cameo glass and has served as an inspiration to many glass and porcelain ...

, an example of Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

cameo glass

Cameo glass is a luxury form of glass art produced by cameo glass engraving or etching and carving through fused layers of differently colored glass to produce designs, usually with white opaque glass figures and motifs on a dark-colored backgroun ...

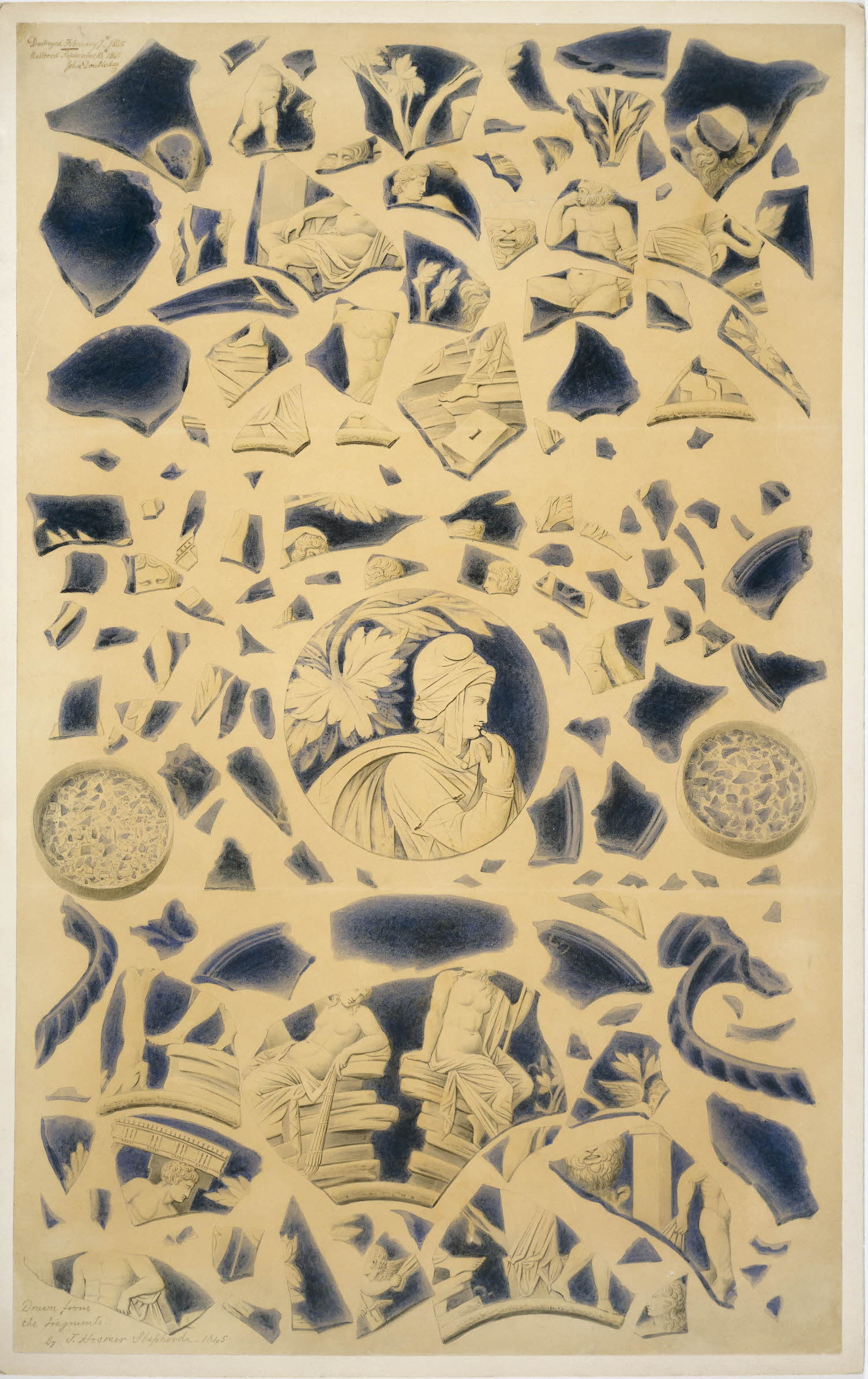

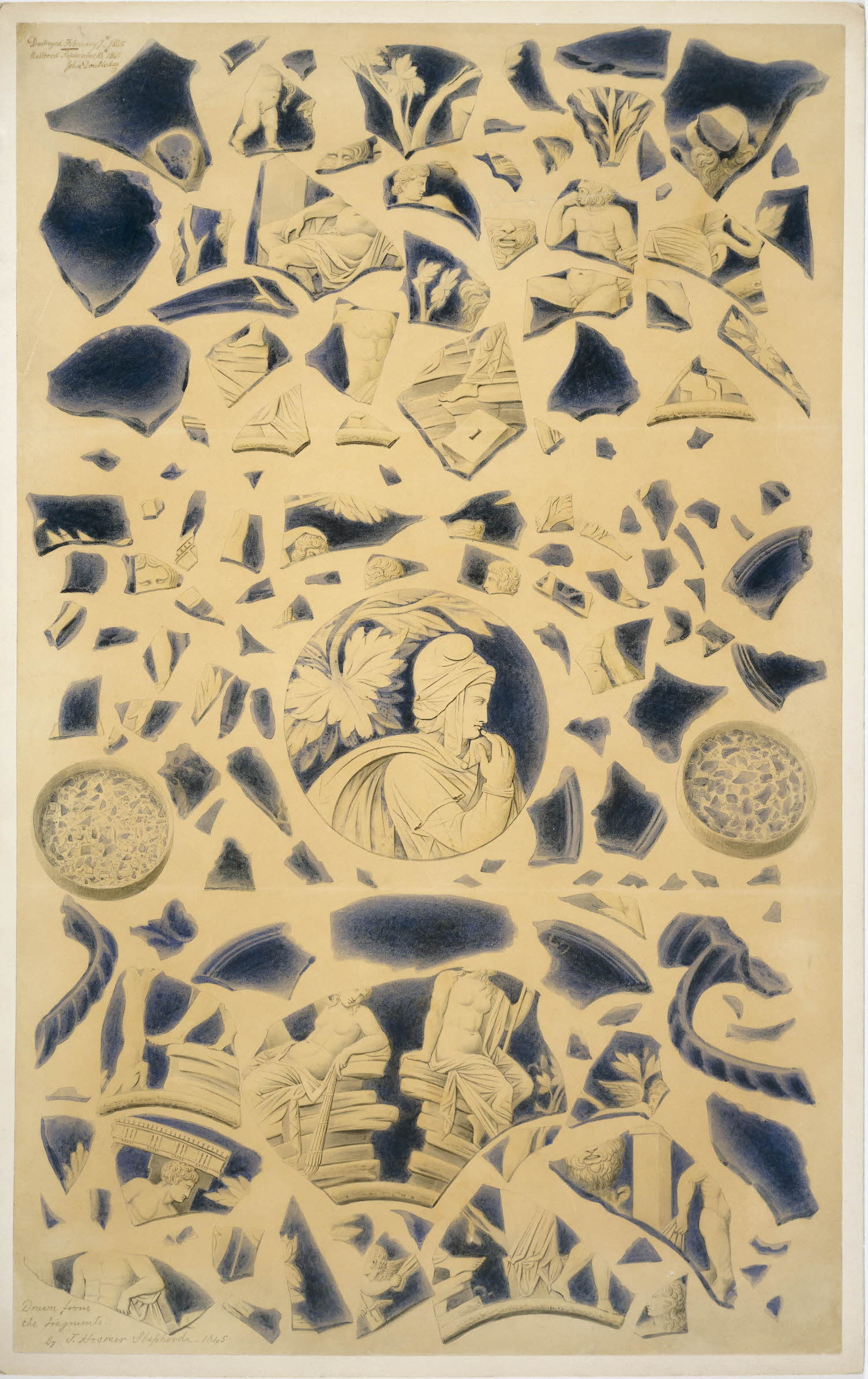

and among the most famous glass items in the world, into hundreds of pieces. After his selection for the restoration, Doubleday commissioned a watercolour painting

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour (British English; see spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin ''aqua'' "water"), is a painting method”Watercolor may be as old as art itself, going back to t ...

of the fragments by Thomas H. Shepherd

Thomas Hosmer Shepherd (16 January 1793, France – 1864) was a British topographical watercolour artist well known for his architectural paintings.

Life and work

Thomas was the brother of topographical artist George "Sidney" Shepherd ...

. No account of his restoration survives, but on 1 May he discussed it in front of the Society of Antiquaries of London

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Societ ...

, and by 10 September he had glued the vase whole again. Only 37 small splinters, most from the interior or thickness of the vase, were left out; the cameo base disc, which was found to be a modern replacement, was set aside for separate display. A new base disc of plain glass, with a polished exterior and matte

Matte may refer to:

Art

* paint with a non-glossy finish. See diffuse reflection.

* a framing element surrounding a painting or watercolor within the outer frame

Film

* Matte (filmmaking), filmmaking and video production technology

* Matte p ...

interior, was diamond-engraved "Broke Feby 7th 1845 Restored Sept 10th 1845 By John Doubleday". The British Museum awarded Doubleday an additional £25 () for his work.

At the time the restoration was termed "masterly" and Doubleday was lauded by ''The Gentleman's Magazine

''The Gentleman's Magazine'' was a monthly magazine founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term ''magazine'' (from the French ''magazine'' ...

'' for demonstrating "skilful ingenuity" and "cleverness ... sufficient to establish his immortality as the prince of restorers". In 2006 William Andrew Oddy

William Andrew Oddy, (born 6 January 1942) is a former Keeper of Conservation at the British Museum, notable for his publications on artefact conservation and numismatics, and for the development of the Oddy test. In 1996 he was awarded the F ...

, a former keeper of conservation at the museum, noted that the achievement "must rank him in the forefront of the craftsmen-restorers of his time." Doubleday's restoration would remain for more than 100 years until the adhesive grew increasingly discoloured. The vase was next restored by J. W. R. Axtell in 1948–1949, and then by Nigel Williams in 1988–1989.

Other works

Beyond his work on the Portland Vase, several other of Doubleday's responsibilities at the British Museum have been recorded. In 1851 he successfully undid damaging restoration work by

Beyond his work on the Portland Vase, several other of Doubleday's responsibilities at the British Museum have been recorded. In 1851 he successfully undid damaging restoration work by William Thomas Brande

William Thomas Brande FRS FRSE (11 January 178811 February 1866) was an English chemist.

Biography

Brande was born in Arlington Street, London, England, the youngest son of six children to Augustus Everard Brande an apothecary, originally fro ...

of the Royal Mint

The Royal Mint is the United Kingdom's oldest company and the official maker of British coins.

Operating under the legal name The Royal Mint Limited, it is a limited company that is wholly owned by His Majesty's Treasury and is under an exclus ...

, who in using acid

In computer science, ACID ( atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps. In the context of databases, a sequ ...

to clean bronze bowls from Nimrud

Nimrud (; syr, ܢܢܡܪܕ ar, النمرود) is an ancient Assyrian city located in Iraq, south of the city of Mosul, and south of the village of Selamiyah ( ar, السلامية), in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a majo ...

had caused extreme oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

. Doubleday's method, described at the time only as "a very simple process and without employing acids", is unknown, but may have used warm water with soap.

Doubleday was again called upon when, between 1850 and 1855, the museum received clay tablets from excavations in Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

and Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

. Some were poorly packaged and had developed crystalline deposits rendering the writing illegible. Under the direction of Samuel Birch

Samuel Birch (3 November 1813 – 27 December 1885) was a British Egyptologist and antiquary.

Biography

Birch was the son of a rector at St Mary Woolnoth, London. He was educated at Merchant Taylors' School. From an early age, his manifest ...

, then the keeper of the Department of Oriental Antiquities, Doubleday attempted to remove the deposits. The results were described by E. A. Wallis Budge, former keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian antiquities at the museum, as "disastrous", but by modern reasoning as "prescient", for though unsuccessful, the underlying methods were subsequently refined by others. Doubleday first attempted to harden the tablets by firing

Dismissal (also called firing) is the termination of employment by an employer against the will of the employee. Though such a decision can be made by an employer for a variety of reasons, ranging from an economic downturn to performance-related ...

them, but this resulted in the flaking of the surfaces, destroying the inscriptions. His second attempt, submerging the tablets in solutions, also resulted in disintegration, at which point Birch suspended the efforts entirely. Later attempts by other conservators in firing similar tablets were more successful; mainstream acceptance today is more tempered by concerns about reversibility than by concerns about efficacy. Doubleday is regarded as the inventor of this method, and his failures may have been caused by raising or lowering the temperature too quickly.

Doubleday twice served as a witness in criminal matters. In 1841 he testified about his analysis of a gold medal during a trial concerning its theft. Eight years later Doubleday again testified, in March and April 1849, in a matter concerning the theft of coins from the museum. Early in February, Timolean Vlasto, a fashionable twenty-four-year-old from Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

whose late father, Count Vlasto, had been a diplomat, had been introduced to Charles Newton (later Sir Charles) by a friend, who described Vlasto as a person interested in coins. Vlasto was given unfettered access to the museum's collection. Suspicions were aroused on 24 March, and on Monday the 26th a label was found on the floor; the coin that it described was missing. Upon inspection many more coins could not be found, but some were recovered when a search warrant for Vlasto's lodgings was obtained on Thursday. Doubleday was called to testify on Thursday or Friday; he stated that some of the coins exactly matched sulphur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

casts which he had made before the theft, and that the market value was between £3,000 and £4,000. Vlasto, who was remanded without bail, claimed that the majority of the coins discovered were not the museum's. On 17 April Doubleday again testified, identifying two more coins as belonging to the museum. In early May Vlasto pleaded guilty to the theft of 266 coins from the museum, valued at £500, and another 71, valued at £150, from the house of General Charles Richard Fox

General Charles Richard Fox (6 November 1796 – 13 April 1873) was a British army general, and later a politician.

Background

Fox was born at Brompton, the illegitimate son of Henry Richard Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland, through a liaison wit ...

. Vlasto's lawyer termed him a monomania

In 19th-century psychiatry, monomania (from Greek , one, and , meaning "madness" or "frenzy") was a form of partial insanity conceived as single psychological obsession in an otherwise sound mind.

Types

Monomania may refer to:

* De Clerambaul ...

c who was only interested in collecting, not selling. The pleas met little sympathy. Vlasto was sentenced by the Central Criminal Court to seven years transportation to Australia, and in early 1851 was placed on board the for the journey.

As a dealer

Apart from his work at the British Museum, Doubleday was a dealer and a copyist of coins, medals, and ancient seals. He sold sulphur andwhite metal

The white metals are a series of often decorative bright metal alloys used as a base for plated silverware, ornaments or novelties, as well as any of several lead-based or tin-based alloys used for things like bearings, jewellery, miniature f ...

casts, the former coloured in different hues, at his establishment, which, located near the British Museum, may have helped facilitate his employment there. He also sold curiosities, such as cabinets, snuff boxes, and lead seals purportedly made from materials taken from the charred ruins of the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

with the consent of the Commissioners of Woods and Forests

The Commissioners of Woods, Forests and Land Revenues were established in the United Kingdom in 1810 by merging the former offices of Surveyor General of Woods, Forests, Parks, and Chases and Surveyor General of the Land Revenues of the Crown into ...

, and pieces of wood said to be from a tree planted by Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

. In 1835 Doubleday advertised for sale copies of 6000 Greek coins, 2050 bronze, 1000 silver, and 500 gold Roman coins, and 300 Roman medallions, in addition to other antiquities and what Doubleday termed "the most extensive Collection of Casts in Sulphur of ancient seals ever formed". By 1851 he had casts of more than 10,000 seals, and at his death it was said that he "possessed the largest collection of casts of seals in England, probably in the world." This comprehensiveness led to his contribution to the 1848 ''Monumenta Historica Britannica

''Monumenta Historica Britannica'' (''MHB''); or, ''Materials for the History of Britain, From the Earliest Period'', is an incomplete work by Henry Petrie, the Keeper of the Records of the Tower of London, assisted by John Sharpe. Only the fir ...

'' of a descriptive catalogue of Roman coins relating to Britain. More unique pieces he sometimes exhibited, either himself or by loan to Sir Henry Ellis Henry Ellis may refer to:

* Henry Augustus Ellis (1861–1939), Irish Australian physician and federalist

* Henry Ellis (diplomat) (1788–1855), British diplomat

* Henry Ellis (governor) (1721–1806), explorer, author, and second colonial Gover ...

, to the Society of Antiquaries of London. Doubleday's casts came from a range of places; on good terms with a variety of institutions and collectors, he was permitted to take casts at will from the collections of the British Museum and the ''Bibliothèque nationale

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vir ...

'' in Paris.

Doubleday's casts were inexpensive, and sold widely. He was well known among collectors, and also sold to lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Generally in that type of school the th ...

s; University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

filled out their collection with his casts, finding them cost-effective substitutes for study. This same appearance of realism saw some of Doubleday's copies passed off as real. Doubleday was cast as a forger in Leonard Forrer

Leonard Forrer or Leonhard Forrer (7 November 1869, Winterthur, Switzerland - 17 November 1953, Bromley, United Kingdom) was a Swiss-born numismatist and coin dealer. He was later naturalised as a British subject.Herbert A. Cahn: ''Leonard Forrer ...

's 1904 ''Biographical Dictionary of Medallists'', though with the caveat that " ether he did copies with the intention of deceiving collectors or not is open to doubt".

Personal life

Little is known about Doubleday's personal life, and nothing about his upbringing or education. An 1859 edition of '' The English Cyclopædia'' described him as American, and the

Little is known about Doubleday's personal life, and nothing about his upbringing or education. An 1859 edition of '' The English Cyclopædia'' described him as American, and the 1851 census

The United Kingdom Census of 1851 recorded the people residing in every household on the night of Sunday 30 March 1851, and was the second of the UK censuses to include details of household members. However, this census added considerably to the f ...

as a New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

-born "artist" who was nonetheless a British subject, married to one Elizabeth and father of five daughters, all Londoners. His eldest daughter, also an Elizabeth, was born around 1833, suggesting that Doubleday and his wife had married by then.

Doubleday worked at a printer's shop in his youth for more than 20 years, according to his obituary in '' The Athenæum'', giving him experience through making type in the casting of metal and other materials. Subsequently, he began copying medals, ancient seals, and coins, occasionally devising new methods of doing so; he also prepared castings for the Royal Mint, and become a founding member of the Royal Numismatic Society

The Royal Numismatic Society (RNS) is a learned society and charity based in London, United Kingdom which promotes research into all branches of numismatics. Its patron was Queen Elizabeth II.

Membership

Foremost collectors and researchers, bo ...

. By 1832 he was listed in directories under the heading "Curiosity, shell & picture dealers", and as a dealer in ancient seals. As well as his work at the British Museum, he may have been a collector.

According to the obituary in ''The Athenæum'', Doubleday died "after a long illness" on 25 January 1856, "in the fifty-seventh year of his age". The illness was termed "extreme" by colleagues, such that he was unreachable for months. Obituaries were published in '' The Athenæum'' and ''The Gentleman's Magazine

''The Gentleman's Magazine'' was a monthly magazine founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term ''magazine'' (from the French ''magazine'' ...

'', and he was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery is a cemetery in the Kensal Green area of Queens Park in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London, England. Inspired by Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, it was founded by the barrister George Frederic ...

. His will was made only six days before his death. His entire estate was left to Elizabeth Bewsey, the daughter of a deceased bookkeeper; she was apparently not the Elizabeth to whom Doubleday was married, making it a bequest that seemingly left nothing for his wife or daughters. His library was sold by Sotheby's

Sotheby's () is a British-founded American multinational corporation with headquarters in New York City. It is one of the world's largest brokers of fine and decorative art, jewellery, and collectibles. It has 80 locations in 40 countries, and ...

that April. The 322 lots combined to fetch £228 2 s6 d ().

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Doubleday, John Date of birth unknown Year of birth unknown 1790s births 1856 deaths American emigrants to England Antiquarians Coin designers Conservator-restorers Employees of the British Museum Medallists Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom People from New York (state) Typesetters