John D. Rockefeller Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

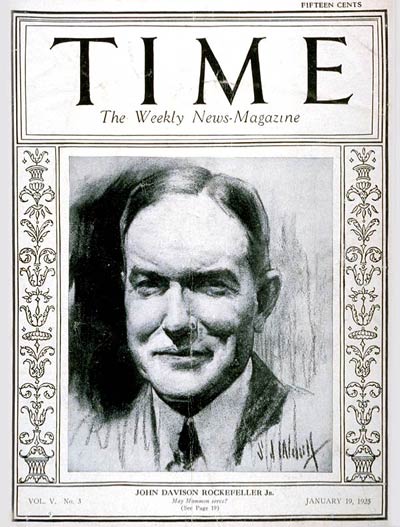

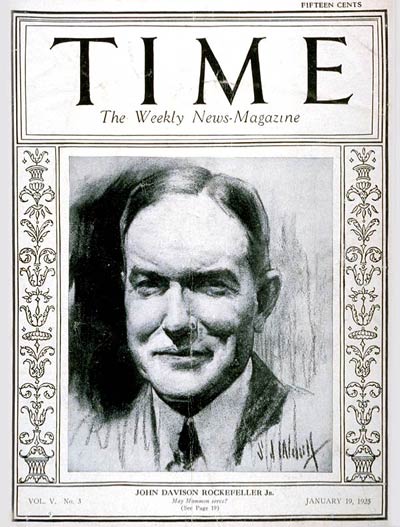

John Davison Rockefeller Jr. (January 29, 1874 – May 11, 1960) was an American financier and philanthropist, and the only son of Standard Oil co-founder

After graduation from Brown, Rockefeller joined his father's business in October 1897, setting up operations in the newly formed

After graduation from Brown, Rockefeller joined his father's business in October 1897, setting up operations in the newly formed  During the Great Depression, he was involved in the financing, development, and construction of the

During the Great Depression, he was involved in the financing, development, and construction of the

In the arts, he gave extensive property he owned on West 54th Street in Manhattan for the site of the

In the arts, he gave extensive property he owned on West 54th Street in Manhattan for the site of the

Michael Gross: 740 Park Avenue

/ref>

online

* Greenspan, Anders. "How philanthropy can alter our view of the past: a look at Colonial Williamsburg". ''Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations'' 5.2 (1994): 193–203. * Hallahan, Kirk. "Ivy Lee and the Rockefellers' response to the 1913-1914 Colorado coal strike". ''Journal of Public Relations Research'' 14#4 (2002): 265–315. * Harr, John Ensor, and Peter J. Johnson. ''The Rockefeller Century'' (1988) * Harvey, Charles E. "John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and the Interchurch World Movement of 1919–1920: A Different Angle on the Ecumenical Movement". ''Church History'' 51#2 (1982): 198–209. * Harvey, Charles E. "John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and the social sciences: An introduction". ''Journal of the History of Sociology'' 4#2 (1982): 1-31. * Henry, Robin. "'In our image, according to our likeness': John D. Rockefeller, jr. and reconstructing manhood in post-Ludlow Colorado". ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 16.1 (2017): 24. * Loebl, Suzanne. ''America's Medicis: The Rockefellers and Their Astonishing Cultural Legacy'' (Harper Collins, 2010). * Manchester, William. ''A Rockefeller Family Portrait: From John D. to Nelson'' (1959) * Moore, Jay D. ''Alcoholics Anonymous and the Rockefeller Connection: How John D. Rockefeller Jr. and his Associates Saved AA'' (2015). * Patmore, Greg. "Employee representation plans at the Minnequa steelworks, Pueblo, Colorado, 1915–1942". ''Business History'' 49.6 (2007): 844–867. * Rausch, Helke. "The Birth of Transnational US Philanthropy from the Spirit of War: Rockefeller Philanthropists in World War I". ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 17.4 (2018): 650–662. * Rees, Jonathan H. ''Representation and Rebellion: The Rockefeller Plan at the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, 1914–1942'' (2011) * Schenkel, Albert F. ''The rich man and the kingdom: John D. Rockefeller Jr., and the Protestant establishment'' (Augsburg Fortress Pub, 1995) * Scott, Nicholas R. "John D. Rockefeller, Jr. & Eugenics: A Means of Social Manipulation". ''Journal of American History'' 61 (1974): 225–26. * Tevis, Martha May. "Philanthropy at its best: The General Education Board’s contributions to education, 1902–1964". ''Journal of Philosophy & History of Education'' 64.1 (2014): 63–72.

Rockefeller Archive Center: Extended Biography

The Architect of Colonial Williamsburg: William Graves Perry, by Will Molineux An article from the Colonial Williamsburg Journal, 2004, outlining Rockefeller's involvement

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Rockefeller, John D. Jr. 1874 births 1960 deaths Acadia National Park American art collectors American financiers American officials of the United Nations American people of English descent American people of German descent American people of Scotch-Irish descent Baptists from New York (state) Brown University alumni Browning School alumni Businesspeople from New York City Fathers of vice presidents of the United States Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur Deaths from pneumonia in Arizona Mount Desert Island Philanthropists from New York (state) Rockefeller Center Rockefeller family Rockefeller Foundation people

John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He has been widely considered the wealthiest American of all time and the richest person in modern history. Rockefeller was ...

.

He was involved in the development of the vast office complex in Midtown Manhattan known as Rockefeller Center

Rockefeller Center is a large complex consisting of 19 commercial buildings covering between 48th Street and 51st Street in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. The 14 original Art Deco buildings, commissioned by the Rockefeller family, span th ...

, making him one of the largest real estate holders in the city. Towards the end of his life, he was famous for his philanthropy, donating over $500 million to a wide variety of different causes, including educational establishments. Among his projects was the reconstruction of Colonial Williamsburg

Colonial Williamsburg is a living-history museum and private foundation presenting a part of the historic district in the city of Williamsburg, Virginia, United States. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation has 7300 employees at this location a ...

in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. He was widely blamed for having orchestrated the Ludlow Massacre and other offenses during the Colorado Coalfield War

The Colorado Coalfield War was a major labor uprising in the Southern and Central Colorado Front Range between September 1913 and December 1914. Striking began in late summer 1913, organized by the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) agai ...

.

Rockefeller was the father of six children: Abby, John III, Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

, Laurance Laurance is a surname or given name. Notable people with the name include:

Surname

* John Laurance (1750–1810), American lawyer and politician from New York

* William F. Laurance (born 1957), American-Australian biology professor

* Bill Laurance ...

, Winthrop, and David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

.

Early life

Rockefeller was the fifth and last child of Standard Oil co-founder John Davison Rockefeller Sr. and schoolteacher Laura Celestia "Cettie" Spelman. His four older sisters were Elizabeth (Bessie), Alice (who died an infant), Alta, andEdith

Edith is a feminine given name derived from the Old English words ēad, meaning 'riches or blessed', and is in common usage in this form in English, German, many Scandinavian languages and Dutch. Its French form is Édith. Contractions and var ...

. Living in his father's mansion at 4 West 54th Street

54th Street is a two-mile-long (3.2 km), one-way street traveling west to east across Midtown Manhattan.

Notable places, west to east

Twelfth Avenue

*The route begins at Twelfth Avenue ( New York Route 9A). Opposite the intersection is the N ...

, he attended Park Avenue Baptist Church at 64th Street (now Central Presbyterian Church) and the Browning School

The Browning School is an independent school for boys in New York City. It was founded in 1888 by John A. Browning. It offers instruction in grades kindergarten through 12th grade. The school is a member of the New York Interschool consortium.

...

, a tutorial establishment set up for him and other children of associates of the family; it was located in a brownstone owned by the Rockefellers, on West 55th Street. His father John Sr. and uncle William A. Rockefeller Jr.

William Avery Rockefeller Jr. (May 31, 1841 – June 24, 1922) was an American businessman and financier. Rockefeller was a co-founder of Standard Oil along with his elder brother John Davison Rockefeller. He was also part owner of the Anacond ...

co-founded Standard Oil together.

Initially, he had intended to go to Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

but was encouraged by William Rainey Harper

William Rainey Harper (July 24, 1856 – January 10, 1906) was an American academic leader, an accomplished semiticist, and Baptist clergyman. Harper helped to establish both the University of Chicago and Bradley University and served as the ...

, president of the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, among others, to enter the Baptist-oriented Brown University instead. Nicknamed "Johnny Rock" by his roommates, he joined both the Glee and the Mandolin clubs, taught a Bible class, and was elected junior class president. Scrupulously careful with money, he stood out as different from other rich men's sons.

In 1897, he graduated with the degree of Bachelor of Arts, after taking nearly a dozen courses in the social sciences, including a study of Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

's ''Das Kapital

''Das Kapital'', also known as ''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' or sometimes simply ''Capital'' (german: Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, link=no, ; 1867–1883), is a foundational theoretical text in materialist phi ...

''. He joined the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

.

Business career

After graduation from Brown, Rockefeller joined his father's business in October 1897, setting up operations in the newly formed

After graduation from Brown, Rockefeller joined his father's business in October 1897, setting up operations in the newly formed family office

A family office is a privately held company that handles investment management and wealth management for a wealthy family, generally one with at least $50-$100 million in investable assets, with the goal being to effectively grow and transfer ...

at 26 Broadway

26 Broadway, also known as the Standard Oil Building or Socony–Vacuum Building, is an office building adjacent to Bowling Green in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. The 31-story, structure was designed in the Renai ...

where he became a director of Standard Oil. He later also became a director at J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age. As the head of the banking firm that ultimately became known ...

's U.S. Steel company, which had been formed in 1901. Junior resigned from both companies in 1910 in an attempt to "purify" his ongoing philanthropy from commercial and financial interests after the Hearst media empire unearthed a bribery scandal involving John Dustin Archbold

John Dustin Archbold (July 26, 1848 – December 6, 1916) was an American businessman and one of the United States' earliest oil refiners. His small oil company was bought out by John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil Company. Archbold rose rapidl ...

(the successor to Senior as head of Standard Oil) and two prominent members of Congress.

In September 1913, the United Mine Workers of America

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the Unit ...

declared a strike against the Colorado Fuel and Iron

The Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I) was a large steel conglomerate founded by the merger of previous business interests in 1892.Scamehorn, Chapter 1, "The Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, 1892-1903" page 10 By 1903 it was mainly owned and co ...

(CF&I) company in what would become the Colorado Coalfield War

The Colorado Coalfield War was a major labor uprising in the Southern and Central Colorado Front Range between September 1913 and December 1914. Striking began in late summer 1913, organized by the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) agai ...

. Junior owned a controlling interest

A controlling interest is an ownership interest in a corporation with enough voting stock shares to prevail in any stockholders' motion. A majority of voting shares (over 50%) is always a controlling interest. When a party holds less than the major ...

in CF&I (40% of its stock) and sat on the board as an absentee director. In April 1914, after a long period of industrial unrest, the Ludlow Massacre occurred at a tent camp occupied by striking miners. At least 20 men, women, and children died in the slaughter. This was followed by nine days of violence between miners and the Colorado National Guard

The Colorado National Guard consists of the Colorado Army National Guard and Colorado Air National Guard, forming the state of Colorado's component to the United States National Guard. Founded in 1860, the Colorado National Guard falls under t ...

. Although he did not order the attack that began this unrest, there are accounts to suggest Junior was mostly to blame for the violence, with the awful working conditions, death ratio, and no paid dead work which included securing unstable ceilings, workers were forced into working in unsafe conditions just to make ends meet. In January 1915, Junior was called to testify before the Commission on Industrial Relations

The Commission on Industrial Relations (also known as the Walsh Commission) p. 12. was a commission created by the U.S. Congress on August 23, 1912, to scrutinize US labor law. The commission studied work conditions throughout the industrial Uni ...

. Many critics blamed Rockefeller for ordering the massacre. Margaret Sanger wrote an attack piece in her magazine ''The Woman Rebel'', declaring, "But remember Ludlow! Remember the men and women and children who were sacrificed in order that John D. Rockefeller Jr., might continue his noble career of charity and philanthropy as a supporter of the Christian faith."

He was at the time being advised by William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A L ...

and the pioneer public relations expert, Ivy Lee

Ivy Ledbetter Lee (July 16, 1877 – November 9, 1934) was an American publicity expert and a founder of modern public relations. Lee is best known for his public relations work with the Rockefeller Family.

His first major client was the Penns ...

. Lee warned that the Rockefellers were losing public support and developed a strategy that Junior followed to repair it. It was necessary for Junior to overcome his shyness, go personally to Colorado to meet with the miners and their families, inspect the conditions of the homes and the factories, attend social events, and especially to listen closely to the grievances. This was novel advice and attracted widespread media attention, which opened the way to resolve the conflict, and present a more humanized version of the Rockefellers. Mackenzie King said Rockefeller's testimony was the turning point in Junior's life, restoring the reputation of the family name; it also heralded a new era of industrial relations in the country.

During the Great Depression, he was involved in the financing, development, and construction of the

During the Great Depression, he was involved in the financing, development, and construction of the Rockefeller Center

Rockefeller Center is a large complex consisting of 19 commercial buildings covering between 48th Street and 51st Street in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. The 14 original Art Deco buildings, commissioned by the Rockefeller family, span th ...

, a vast office complex in midtown Manhattan, and as a result, became one of the largest real estate holders in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

. He was influential in attracting leading blue-chip corporations as tenants in the complex, including GE and its then affiliates RCA

The RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded as the Radio Corporation of America in 1919. It was initially a patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse, AT&T Corporation and United Fruit Comp ...

, NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American English-language commercial broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a division of Comcast, its headquarters are l ...

and RKO

RKO Radio Pictures Inc., commonly known as RKO Pictures or simply RKO, was an American film production and distribution company, one of the "Big Five" film studios of Hollywood's Golden Age. The business was formed after the Keith-Albee-Orpheu ...

, as well as Standard Oil of New Jersey

ExxonMobil, an American multinational oil and gas corporation presently based out of Texas, has had one of the longest histories of any company in its industry. A direct descendant of John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil, the company traces its roo ...

(now ExxonMobil), Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. ne ...

, Time Inc

Time Inc. was an American worldwide mass media corporation founded on November 28, 1922, by Henry Luce and Briton Hadden and based in New York City. It owned and published over 100 magazine brands, including its namesake ''Time'', ''Sports Il ...

, and branches of Chase National Bank

JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., doing business as Chase Bank or often as Chase, is an American national bank headquartered in New York City, that constitutes the consumer and commercial banking subsidiary of the U.S. multinational banking and fina ...

(now JP Morgan Chase

JPMorgan Chase & Co. is an American multinational investment bank and financial services holding company headquartered in New York City and incorporated in Delaware. As of 2022, JPMorgan Chase is the largest bank in the United States, the w ...

).

The family office, of which he was in charge, shifted from 26 Broadway to the 56th floor of the landmark 30 Rockefeller Plaza

30 Rockefeller Plaza (officially the Comcast Building; formerly RCA Building and GE Building) is a skyscraper that forms the centerpiece of Rockefeller Center in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. Completed in 1933, the 66-s ...

upon its completion in 1933. The office formally became "Rockefeller Family and Associates" (and informally, "Room 5600").

In 1921, Junior received about 10% of the shares of the Equitable Trust Company

JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., doing business as Chase Bank or often as Chase, is an American national bank headquartered in New York City, that constitutes the consumer and commercial banking subsidiary of the U.S. multinational banking and fina ...

from his father, making him the bank's largest shareholder. Subsequently, in 1930, Equitable merged with Chase National Bank, making Chase the largest bank in the world at the time. Although his stockholding was reduced to about 4% following this merger, he was still the largest shareholder in what became known as "the Rockefeller bank". As late as the 1960s, the family still retained about 1% of the bank's shares, by which time his son David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

had become the bank's president.

In the late 1920s, Rockefeller founded the Dunbar National Bank in Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Ha ...

. The financial institution was located within the Paul Laurence Dunbar Apartments at 2824 Eighth Avenue near 150th Street, servicing a primarily African-American clientele. It was unique among New York City financial institutions in that it employed African Americans as tellers, clerks and bookkeepers as well as in key management positions. However, the bank folded after only a few years of operation.

Philanthropy and social causes

In a celebrated letter toNicholas Murray Butler

Nicholas Murray Butler () was an American philosopher, diplomat, and educator. Butler was president of Columbia University, president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, and the deceased Ja ...

in June 1932, subsequently printed on the front page of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', Rockefeller, a lifelong teetotaler, argued against the continuation of the Eighteenth Amendment on the principal grounds of an increase in disrespect for the law. This letter became an important event in pushing the nation to repeal Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcohol ...

.

Rockefeller was known for his philanthropy, giving over $537 million to myriad causes over his lifetime compared to $240 million to his own family. He created the Sealantic Fund in 1938 to channel gifts to his favorite causes; previously his main philanthropic organization had been the Davison Fund. He had become the Rockefeller Foundation's inaugural president in May 1913 and proceeded to dramatically expand the scope of this institution, founded by his father. Later he would become involved in other organizations set up by Senior: Rockefeller University and the International Education Board.

In the social sciences, he founded the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial in 1918, which was subsequently folded into the Rockefeller Foundation in 1929. A committed internationalist, he financially supported programs of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

and crucially funded the formation and ongoing expenses of the Council on Foreign Relations and its initial headquarters building in New York in 1921.

He established the Bureau of Social Hygiene in 1913, a major initiative that investigated such social issues as prostitution and venereal disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are Transmission (medicine), spread by Human sexual activity, sexual activity, especi ...

, as well as studies in police administration and support for birth control clinics and research. In 1924, at the instigation of his wife, he provided crucial funding for Margaret Sanger–who had previously been a personal opponent to him due to his treatment of workers–in her work on birth control and involvement in population issues. He donated $5000 to her American Birth Control League in 1924 and a second time in 1925.

In the arts, he gave extensive property he owned on West 54th Street in Manhattan for the site of the

In the arts, he gave extensive property he owned on West 54th Street in Manhattan for the site of the Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is an art museum located in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, on 53rd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues.

It plays a major role in developing and collecting modern art, and is often identified as one of ...

, which had been co-founded by his wife in 1929.

In 1925, he purchased the George Grey Barnard

George Grey Barnard (May 24, 1863 – April 24, 1938), often written George Gray Barnard, was an American sculptor who trained in Paris. He is especially noted for his heroic sized '' Struggle of the Two Natures in Man'' at the Metropolitan Museu ...

collection of medieval art and cloister fragments for the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

. He also purchased land north of the original site, now Fort Tryon Park

Fort Tryon Park is a public park located in the Hudson Heights and Inwood neighborhoods of the borough of Manhattan in New York City. The park is situated on a ridge in Upper Manhattan, close to the Hudson River to the west. It extends most ...

, for a new building, The Cloisters

The Cloisters, also known as the Met Cloisters, is a museum in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Upper Manhattan, New York City. The museum, situated in Fort Tryon Park, specializes in European medieval art and architecture, with a fo ...

.

In November 1926, Rockefeller came to the College of William and Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William III ...

for the dedication of an auditorium built-in memory of the organizers of Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

, the honorary scholastic fraternity founded in Williamsburg in 1776. Rockefeller was a member of the society and had helped pay for the auditorium. He had visited Williamsburg the previous March, when the Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin

William Archer Rutherfoord Goodwin (June 18, 1869 – September 7, 1939) (or W.A.R. Goodwin as he preferred or "the Doctor" as commonly used to his annoyance) was an Episcopal priest, historian, and author. As the rector of Bruton Parish Church, ...

escorted him—along with his wife Abby, and their sons, David, Laurance, and Winthrop—on a quick tour of the city. The upshot of his visit was that he approved the plans already developed by Goodwin and launched the massive historical restoration of Colonial Williamsburg

Colonial Williamsburg is a living-history museum and private foundation presenting a part of the historic district in the city of Williamsburg, Virginia, United States. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation has 7300 employees at this location a ...

on November 22, 1927. Amongst many other buildings restored through his largesse was The College of William & Mary's Wren Building and the Episcopalian Bruton Parish Church

Bruton Parish Church is located in the restored area of Colonial Williamsburg in Williamsburg, Virginia, United States. It was established in 1674 by the consolidation of two previous parishes in the Virginia Colony, and remains an active Epi ...

.

In 1940, Rockefeller hosted Bill Wilson, one of the original founders of Alcoholics Anonymous, and others at a dinner to tell their stories. "News of this got out on the world wires; inquiries poured in again and many people went to the bookstores to get the book, ''Alcoholics Anonymous''." Rockefeller offered to pay for the publication of the book, but in keeping with AA traditions of being self-supporting, AA rejected the money.

Through negotiations by his son Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

, in 1946 he bought for $8.5 million—from the major New York real estate developer William Zeckendorf

William Zeckendorf Sr. (June 30, 1905 – September 30, 1976) was a prominent American real estate developer. Through his development company Webb and Knapp — for which he began working in 1938 and which he purchased in 1949 — he developed ...

—the land along the East River in Manhattan which he later donated for the United Nations headquarters

zh, 联合国总部大楼french: Siège des Nations uniesrussian: Штаб-квартира Организации Объединённых Наций es, Sede de las Naciones Unidas

, image = Midtown Manhattan Skyline 004.jpg

, im ...

. This was after he had vetoed the family estate at Pocantico as a prospective site for the headquarters (see Kykuit

Kykuit ( ), known also as the John D. Rockefeller Estate, is a 40-room historic house museum in Pocantico Hills, a hamlet in the town of Mount Pleasant, New York 25 miles north of New York City. The house was built for oil tycoon and Rockefelle ...

). Another UN connection was his early financial support for its predecessor, the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

; this included a gift to endow a major library for the League in Geneva which today still remains a resource for the UN.

A confirmed ecumenicist, over the years he gave substantial sums to Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

and Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

institutions, ranging from the Interchurch World Movement The Interchurch World Movement was an attempt to unite some of the main enterprises of the Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking t ...

, the Federal Council of Churches, the Union Theological Seminary, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York's Riverside Church

Riverside Church is an interdenominational church in the Morningside Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, on the block bounded by Riverside Drive, Claremont Avenue, 120th Street and 122nd Street near Columbia University's Mornin ...

, and the World Council of Churches

The World Council of Churches (WCC) is a worldwide Christian inter-church organization founded in 1948 to work for the cause of ecumenism. Its full members today include the Assyrian Church of the East, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, most ju ...

. He was also instrumental in the development of the research that led to Robert and Helen Lynd's famous Middletown studies

The Middletown studies were sociological case studies of the white residents of the city of Muncie in Indiana initially conducted by Robert Staughton Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd, husband-and-wife sociologists. The Lynds' findings were detailed in ...

work that was conducted in the city of Muncie, Indiana, that arose out of the financially supported Institute of Social and Religious Research.

As a follow on to his involvement in the Ludlow Massacre, Rockefeller was a major initiator with his close friend and advisor William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A L ...

in the nascent industrial relations movement; along with major chief executives of the time, he incorporated Industrial Relations Counselors (IRC) in 1926, a consulting firm whose main goal was to establish industrial relations as a recognized academic discipline at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

and other institutions. It succeeded through the support of prominent corporate chieftains of the time, such as Owen D. Young

Owen D. Young (October 27, 1874July 11, 1962) was an American industrialist, businessman, lawyer and diplomat at the Second Reparations Conference (SRC) in 1929, as a member of the German Reparations International Commission.

He is known for t ...

and Gerard Swope

Gerard Swope (December 1, 1872 – November 20, 1957) was an American electronics businessman. He served as the president of General Electric Company between 1922 and 1940, and again from 1942 until 1945. During this time Swope expanded GE's produ ...

of General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable en ...

.

Overseas philanthropy

In the 1920s, he also donated a substantial amount towards the restoration and rehabilitation of major buildings in France afterWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, such as the Reims Cathedral

, image = Reims Kathedrale.jpg

, imagealt = Facade, looking northeast

, caption = Façade of the cathedral, looking northeast

, pushpin map = France

, pushpin map alt = Location within France

, ...

, the Château de Fontainebleau

Palace of Fontainebleau (; ) or Château de Fontainebleau, located southeast of the center of Paris, in the commune of Fontainebleau, is one of the largest French royal châteaux. The medieval castle and subsequent palace served as a residence ...

and the Château de Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed ...

, for which in 1936 he was awarded France's highest decoration, the Grand-Croix de la Legion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

, which also was awarded decades later to his son David Rockefeller.

He also liberally funded the notable early excavations at Luxor

Luxor ( ar, الأقصر, al-ʾuqṣur, lit=the palaces) is a modern city in Upper (southern) Egypt which includes the site of the Ancient Egyptian city of ''Thebes''.

Luxor has frequently been characterized as the "world's greatest open-a ...

in Egypt, and the American School of Classical Studies for excavation of the Agora and the reconstruction of the Stoa of Attalos, both in Athens; the American Academy in Rome; Lingnan University

Lingnan University (LN/LU), formerly called Lingnan College, is a public liberal arts university in Hong Kong. It aims to provide students with an education in the liberal arts tradition and has joined the Global Liberal Arts Alliance since ...

in China; St. Luke's International Hospital in Tokyo; the library of the Imperial University in Tokyo; and the Shakespeare Memorial Endowment at Stratford-on-Avon.

In addition, he provided the funding for the construction of the Palestine Archaeological Museum in East Jerusalem – the Rockefeller Museum

The Rockefeller Archeological Museum, formerly the Palestine Archaeological Museum ("PAM"; 1938–1967), and which before then housed The Imperial Museum of Antiquities (''Müze-i Hümayun''; 1901–1917), is an archaeology museum located in East ...

– which today houses many antiquities and was the home of many of the Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls (also the Qumran Caves Scrolls) are ancient Jewish and Hebrew religious manuscripts discovered between 1946 and 1956 at the Qumran Caves in what was then Mandatory Palestine, near Ein Feshkha in the West Bank, on the ...

until they were moved to the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum.

Conservation

He had a special interest in conservation, and purchased and donated land for many AmericanNational Parks

A national park is a natural park in use for conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individua ...

, including Grand Teton

Grand Teton is the highest mountain in Grand Teton National Park, in Northwest Wyoming, and a classic destination in American mountaineering.

Geography

Grand Teton, at , is the highest point of the Teton Range, and the second highest peak in t ...

(hiding his involvement and intentions behind the Snake River Land Company The Snake River Land Company or the Snake River Cattle and Stock Company was a land purchasing company established in 1927 by philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, Jr. The company acted as a front so Rockefeller could buy land in the Jackson Hole val ...

), Mesa Verde National Park

Mesa Verde National Park is an American national park and UNESCO World Heritage Site located in Montezuma County, Colorado. The park protects some of the best-preserved Ancestral Puebloan archaeological sites in the United States.

Established ...

, Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

, Great Smoky Mountains

The Great Smoky Mountains (, ''Equa Dutsusdu Dodalv'') are a mountain range rising along the Tennessee–North Carolina border in the southeastern United States. They are a subrange of the Appalachian Mountains, and form part of the Blue Ridge ...

, Yosemite, and Shenandoah. In the case of Acadia National Park, he financed and engineered an extensive Carriage Road network throughout the park. Both the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway that connects Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowst ...

to the Grand Teton National Park

Grand Teton National Park is an American national park in northwestern Wyoming. At approximately , the park includes the major peaks of the Teton Range as well as most of the northern sections of the valley known as Jackson Hole. Grand Teton ...

and the Rockefeller Memorial in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park were named after him. He was also active in the movement to save redwood trees, making a significant contribution to Save the Redwoods League

Save the Redwoods League is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to protect and restore coast redwood (''Sequoia sempervirens'') and giant sequoia (''Sequoiadendron giganteum'') trees through the preemptive purchase of development rights ...

in the 1920s to enable the purchase of what would become the Rockefeller Forest in Humboldt Redwoods State Park.

In 1951, he established ''Sleepy Hollow Restorations'', which brought together under one administrative body the management and operation of two historic sites he had acquired: Philipsburg Manor House

Philipsburg Manor House is a historic house in the Upper Mills section of the former sprawling Colonial-era estate known as Philipsburg Manor. Together with a water mill and trading site the house is operated as a non-profit museum by Historic H ...

in North Tarrytown, now called Sleepy Hollow (acquired in 1940 and donated to the Tarrytown

Tarrytown is a village in the town of Greenburgh in Westchester County, New York. It is located on the eastern bank of the Hudson River, approximately north of Midtown Manhattan in New York City, and is served by a stop on the Metro-North Hu ...

Historical Society), and ''Sunnyside'', Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

's home, acquired in 1945. He bought Van Cortland Manor in Croton-on-Hudson in 1953 and in 1959 donated it to Sleepy Hollow Restorations. In all, he invested more than $12 million in the acquisition and restoration of the three properties that were the core of the organization's holdings. In 1986, Sleepy Hollow Restorations became ''Historic Hudson Valley'', which also operates the current guided tours of the Rockefeller family estate of Kykuit

Kykuit ( ), known also as the John D. Rockefeller Estate, is a 40-room historic house museum in Pocantico Hills, a hamlet in the town of Mount Pleasant, New York 25 miles north of New York City. The house was built for oil tycoon and Rockefelle ...

in Pocantico Hills.

He is the author of the noted life principle, among others, inscribed on a tablet facing his famed Rockefeller Center

Rockefeller Center is a large complex consisting of 19 commercial buildings covering between 48th Street and 51st Street in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. The 14 original Art Deco buildings, commissioned by the Rockefeller family, span th ...

: "I believe that every right implies a responsibility; every opportunity, an obligation; every possession, a duty".

In 1935, Rockefeller received The Hundred Year Association of New York

The Hundred Year Association of New York, founded in 1927, is a non-profit organization in New York City that recognizes and rewards dedication and service to the City of New York by businesses and organizations that have been in operation in the ...

's Gold Medal Award, "in recognition of outstanding contributions to the City of New York." He was awarded the Public Welfare Medal The Public Welfare Medal is awarded by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences "in recognition of distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare." It is the most prestigious honor conferred by the academy. First award ...

from the National Academy of Sciences in 1943.

Family

In August 1900, Rockefeller was invited by the powerful senator Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich ofRhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

to join a party aboard President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

's yacht, the USS ''Dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal within the infraorder Cetacea. Dolphin species belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (the ...

'', on a cruise to Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

. Although the outing was of a political nature, Rockefeller's future wife, philanthropist/socialite Abigail Greene "Abby" Aldrich, was included in the large party; the two had first met in the fall of 1894 and had been courting for over four years.

Rockefeller married Abby on October 9, 1901, in what was seen at the time as the consummate marriage of capitalism and politics. She was a daughter of Senator Aldrich and Abigail Pearce Truman "Abby" Chapman. Moreover, their wedding was the major social event of its time - one of the most lavish of the Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Wes ...

. It was held at the Aldrich Mansion

Aldrich Mansion is a late 19th-century property owned by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Providence since 1939. It is located by the scenic Narragansett Bay at 836 Warwick Neck Avenue in Warwick, Rhode Island, south of Providence, Rhode Island. Or ...

at Warwick Neck, Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

, and attended by executives of Standard Oil and other companies.

The couple had six children; Abby in 1903, John III in 1906, Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

in 1908, Laurance Laurance is a surname or given name. Notable people with the name include:

Surname

* John Laurance (1750–1810), American lawyer and politician from New York

* William F. Laurance (born 1957), American-Australian biology professor

* Bill Laurance ...

in 1910, Winthrop in 1912, and David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

in 1915.

Abby died of a heart attack at the family apartment at 740 Park Avenue in April 1948. Junior remarried in 1951, to Martha Baird, the widow of his old college classmate Arthur Allen. Rockefeller died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

on May 11, 1960, at the age of 86 in Tucson, Arizona, and was interred in the family cemetery in Tarrytown

Tarrytown is a village in the town of Greenburgh in Westchester County, New York. It is located on the eastern bank of the Hudson River, approximately north of Midtown Manhattan in New York City, and is served by a stop on the Metro-North Hu ...

, with 40 family members present.

His sons, the five Rockefeller brothers, established an extensive network of social connections and institutional power over time, based on the foundations that Junior - and before him Senior - had laid down. David became a prominent banker, philanthropist and world statesman. Abby and John III became philanthropists. Laurance became a venture capitalist and conservationist. Nelson and Winthrop Rockefeller later became state governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

s; Nelson went on to serve as Vice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice ...

under President Gerald Ford.

Residences

From 1901 to 1913, Junior lived at13 West 54th Street

13 and 15 West 54th Street (also the William Murray Residences) are two commercial buildings in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. They are along 54th Street's northern sidewalk between Fifth Avenue and Sixth Avenue. The fo ...

in New York. Afterward, Junior's principal residence in New York was the 9-story mansion at 10 West 54th Street, but he owned a group of properties in this vicinity, including Nos. 4, 12, 14 and 16 (some of these properties had been previously acquired by his father, John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He has been widely considered the wealthiest American of all time and the richest person in modern history. Rockefeller was ...

). After he vacated No. 10 in 1936, these properties were razed and subsequently all the land was gifted to his wife's Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is an art museum located in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, on 53rd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues.

It plays a major role in developing and collecting modern art, and is often identified as one of ...

. In that year he moved into a luxurious 40-room triplex apartment at 740 Park Avenue

740 Park Avenue is a luxury cooperative apartment building on the west side of Park Avenue between East 71st and 72nd Streets in the Lenox Hill neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. It was described in ''Business Insider'' in 2011 as "a l ...

. In 1953, the real estate developer William Zeckendorf

William Zeckendorf Sr. (June 30, 1905 – September 30, 1976) was a prominent American real estate developer. Through his development company Webb and Knapp — for which he began working in 1938 and which he purchased in 1949 — he developed ...

bought the 740 Park Avenue apartment complex and then sold it to Rockefeller, who quickly turned the building into a cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-contro ...

, selling it on to his rich neighbors in the building.

Years later, just after his son Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

become Governor of New York, Rockefeller helped foil a bid by greenmail

Greenmail or greenmailing is the action of purchasing enough shares in a firm to challenge a firm's leadership with the threat of a hostile takeover to force the target company to buy the purchased shares back at a premium in order to prevent the ...

er Saul Steinberg

Saul Steinberg (June 15, 1914 – May 12, 1999) was a Romanian-American artist, best known for his work for ''The New Yorker'', most notably '' View of the World from 9th Avenue''. He described himself as "a writer who draws".

Biography

S ...

to take over Chemical Bank. Steinberg bought Junior's apartment for $225,000, $25,000 less than it had cost new in 1929. It has since been called the greatest trophy apartment in New York, in the world's richest apartment building./ref>

Honors and legacy

In 1929, Junior was elected an honorary member of the Georgia Society of the Cincinnati. In 1935, he receivedThe Hundred Year Association of New York

The Hundred Year Association of New York, founded in 1927, is a non-profit organization in New York City that recognizes and rewards dedication and service to the City of New York by businesses and organizations that have been in operation in the ...

's Gold Medal Award "in recognition of outstanding contributions to the City of New York." In 1939, he was elected Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

under statute 12.

The John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library at Brown University, completed in 1964, is named in his honor.

See also

*Forest Hill, Ohio

Forest Hill is an historic neighborhood spanning parts of Cleveland Heights and East Cleveland, Ohio, and is bordered to the north by Glynn Road, the south by Mayfield Road, by Lee Boulevard to the west and North Taylor Road to the east. Forest ...

* John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library

* John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway

* Rockefeller Brothers Fund

The Rockefeller Brothers Fund (RBF) is a philanthropic foundation created and run by members of the Rockefeller family. It was founded in New York City in 1940 as the primary philanthropic vehicle for the five third-generation Rockefeller brothe ...

* Rockefeller family

The Rockefeller family () is an American industrial, political, and banking family that owns one of the world's largest fortunes. The fortune was made in the American petroleum industry during the late 19th and early 20th centuries by brot ...

* Rockefeller Foundation

Citations

Further reading

* Chernow, Ron. ''Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr''. New York: Warner Books, 1998., Detailed biography of his father * Fosdick, Raymond B. ''John D. Rockefeller, Jr.: A Portrait'' (1956), full biographyonline

* Greenspan, Anders. "How philanthropy can alter our view of the past: a look at Colonial Williamsburg". ''Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations'' 5.2 (1994): 193–203. * Hallahan, Kirk. "Ivy Lee and the Rockefellers' response to the 1913-1914 Colorado coal strike". ''Journal of Public Relations Research'' 14#4 (2002): 265–315. * Harr, John Ensor, and Peter J. Johnson. ''The Rockefeller Century'' (1988) * Harvey, Charles E. "John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and the Interchurch World Movement of 1919–1920: A Different Angle on the Ecumenical Movement". ''Church History'' 51#2 (1982): 198–209. * Harvey, Charles E. "John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and the social sciences: An introduction". ''Journal of the History of Sociology'' 4#2 (1982): 1-31. * Henry, Robin. "'In our image, according to our likeness': John D. Rockefeller, jr. and reconstructing manhood in post-Ludlow Colorado". ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 16.1 (2017): 24. * Loebl, Suzanne. ''America's Medicis: The Rockefellers and Their Astonishing Cultural Legacy'' (Harper Collins, 2010). * Manchester, William. ''A Rockefeller Family Portrait: From John D. to Nelson'' (1959) * Moore, Jay D. ''Alcoholics Anonymous and the Rockefeller Connection: How John D. Rockefeller Jr. and his Associates Saved AA'' (2015). * Patmore, Greg. "Employee representation plans at the Minnequa steelworks, Pueblo, Colorado, 1915–1942". ''Business History'' 49.6 (2007): 844–867. * Rausch, Helke. "The Birth of Transnational US Philanthropy from the Spirit of War: Rockefeller Philanthropists in World War I". ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 17.4 (2018): 650–662. * Rees, Jonathan H. ''Representation and Rebellion: The Rockefeller Plan at the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, 1914–1942'' (2011) * Schenkel, Albert F. ''The rich man and the kingdom: John D. Rockefeller Jr., and the Protestant establishment'' (Augsburg Fortress Pub, 1995) * Scott, Nicholas R. "John D. Rockefeller, Jr. & Eugenics: A Means of Social Manipulation". ''Journal of American History'' 61 (1974): 225–26. * Tevis, Martha May. "Philanthropy at its best: The General Education Board’s contributions to education, 1902–1964". ''Journal of Philosophy & History of Education'' 64.1 (2014): 63–72.

Primary sources

* Ernst, Joseph W., and John Davison Rockefeller. ''Dear Father/dear Son: Correspondence of John D. Rockefeller and John D. Rockefeller Jr.'' (Fordham Univ Press, 1994) * Ernst, Joseph W., John Davison Rockefeller, and Horace Marden Albright. ''Worthwhile Places: Correspondence of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and Horace M. Albright'' (Fordham Univ Press, 1991).External links

Rockefeller Archive Center: Extended Biography

The Architect of Colonial Williamsburg: William Graves Perry, by Will Molineux An article from the Colonial Williamsburg Journal, 2004, outlining Rockefeller's involvement

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Rockefeller, John D. Jr. 1874 births 1960 deaths Acadia National Park American art collectors American financiers American officials of the United Nations American people of English descent American people of German descent American people of Scotch-Irish descent Baptists from New York (state) Brown University alumni Browning School alumni Businesspeople from New York City Fathers of vice presidents of the United States Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur Deaths from pneumonia in Arizona Mount Desert Island Philanthropists from New York (state) Rockefeller Center Rockefeller family Rockefeller Foundation people