John Cleves Symmes, Jr on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

For the first two years after the publication of his theory, Symmes confined his promotional efforts to circulars and letters published in newspapers and magazines. In all, he issued seven additional circulars from 1818 to 1819, including ''Light Between the Spheres,'' which gained a national audience via its publication in the ''

For the first two years after the publication of his theory, Symmes confined his promotional efforts to circulars and letters published in newspapers and magazines. In all, he issued seven additional circulars from 1818 to 1819, including ''Light Between the Spheres,'' which gained a national audience via its publication in the ''

''Circular No. 1''

(St. Louis, MO: Privately Publibout the Poles, Compiled by Americus Symmes, from the Writings of his Father, Capt. John Cleves Symmes, 1780–1829.] (Louisville, KY: Bradley & Gilbert, 1878) {{DEFAULTSORT:Symmes, John Cleves Jr. 1779 births 1829 deaths Military personnel from New Jersey Academics from New Jersey Hollow Earth proponents United States Army officers United States Army personnel of the War of 1812 Military personnel from Sussex County, New Jersey

Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

John Cleves Symmes Jr. (November 5, 1780 – May 28, 1829) was an American Army officer, trader, and lecturer. Symmes is best known for his 1818 variant of the Hollow Earth theory, which introduced the concept of openings to the inner world at the poles.

Early life

John Cleves Symmes Jr. was born inSussex County, New Jersey

Sussex County () is the northernmost county in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Its county seat is Newton.John Cleves Symmes

John Cleves Symmes (July 21, 1742February 26, 1814) was a delegate to the Continental Congress from New Jersey, and later a pioneer in the Northwest Territory. He was also the father-in-law of President William Henry Harrison and, thereby, the ...

, a delegate to the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

, a Colonel in the Revolutionary War, Chief Justice of New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

, father-in-law of US President William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was the ninth president of the United States, serving from March 4 to April 4, 1841, the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causin ...

and pioneer in the settlement and development of the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from part of the unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolution. Established ...

. Though Justice Symmes had no male children, the younger John Cleves Symmes was often referred to by his later military rank, or with the suffix of "Jr.", so as to distinguish him from his uncle. Symmes "received a good common English education" and on March 26, 1802, at the age of twenty-two, obtained a commission as an Ensign

Ensign most often refers to:

* Ensign (flag), a flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality

* Ensign (rank), a navy (and former army) officer rank

Ensign or The Ensign may also refer to:

Places

* Ensign, Alberta, Alberta, Canada

* Ensign, Ka ...

in the US Army (with the assistance of his uncle).

He was commissioned into the 1st Infantry Regiment and was promoted to Second Lieutenant on May 1, 1804, to First Lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

on July 29, 1807, and to Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

on January 20, 1813. In 1807, Symmes fought a pistol duel

Pistol dueling was a competitive sport developed around 1900 which involved opponents shooting at each other using dueling pistols adapted to fire wax bullets. The sport was briefly popular among some members of the metropolitan upper classes in t ...

with Lieutenant Marshall. Symmes suffered a wound in his wrist; Marshall one in his thigh. Afterwards, the two men became friends. On December 25, 1808, Symmes married Mary Anne Lockwood (''nee.'' Pelletier), a widow with six children, all of whom he was to raise alongside his own children by Mary.

During the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

, Symmes was initially stationed in Missouri Territory

The Territory of Missouri was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 4, 1812, until August 10, 1821. In 1819, the Territory of Arkansas was created from a portion of its southern area. In 1821, a southe ...

until 1814 when his 1st Infantry Regiment was sent to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, arriving just in time to provide relief to American forces at the Battle of Lundy's Lane

The Battle of Lundy's Lane, also known as the Battle of Niagara or contemporarily as the Battle of Bridgewater, was fought on 25 July 1814, during the War of 1812, between an invading American army and a British and Canadian army near present-d ...

. Symmes also served during the Siege of Fort Erie

The siege of Fort Erie, also known as the Battle of Erie, from 4 August to 21 September 1814, was one of the last engagements of the War of 1812, between British and American forces. It took place during the Niagara campaign, and the Americans ...

, and continued in his Army career until being honorably discharged on June 15, 1815.

After leaving the Army, Symmes moved to St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

(then a frontier settlement) and went into business as a trader. He sold supplies to Army, and obtained a license to trade with the Fox Indians. However, his business venture was unsuccessful and in 1819, Symmes moved his family to Newport, KY. But while failing as a trader, Symmes was contemplating the rings of Saturn

Saturn has the most extensive and complex ring system of any planet in the Solar System. The rings consist of particles in orbit around the planet made almost entirely of water ice, with a trace component of Rock (geology), rocky material. Parti ...

and developing his theory of the Hollow Earth—a theory which he would spend the remainder of his life promoting.

Hollow Earth theory

Declaration and reaction

On April 10, 1818, Symmes announced his Hollow Earth hypothesis to the world, publishing his ''Circular No. 1.'' While a few enthusiastic supporters would ultimately lionize Symmes as the " Newton of the West", in general the world was not impressed. Symmes had sent his declaration (at considerable cost to himself) to "each notable foreign government, reigning prince, legislature, city, college, and philosophical societies, throughout the union, and to individual members of our National Legislature, as far as the five hundred copies would go." Symmes's son Americus wrote of the reaction to ''Circular No. 1'' in 1878, recounting " s reception by the public can easily be imagined; it was overwhelmed with ridicule as the production of a distempered imagination, or the result of partial insanity. It was for many years a fruitful source of jest with the newspapers." Symmes, though, was not deterred. He began a campaign of circulars, newspaper letters, and lectures aimed at defending and promoting his hypothesis of a Hollow Earth—and to build support for a polar expedition to vindicate his theory.Symmes's theory

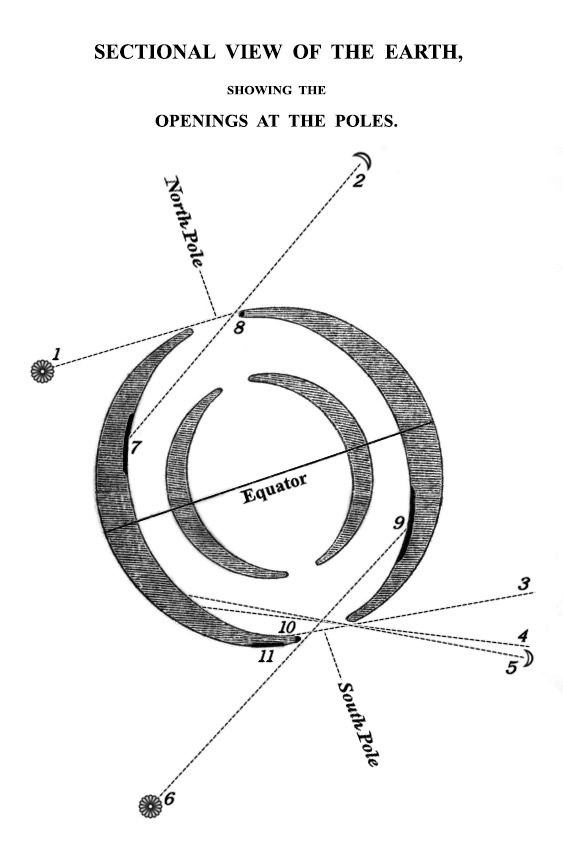

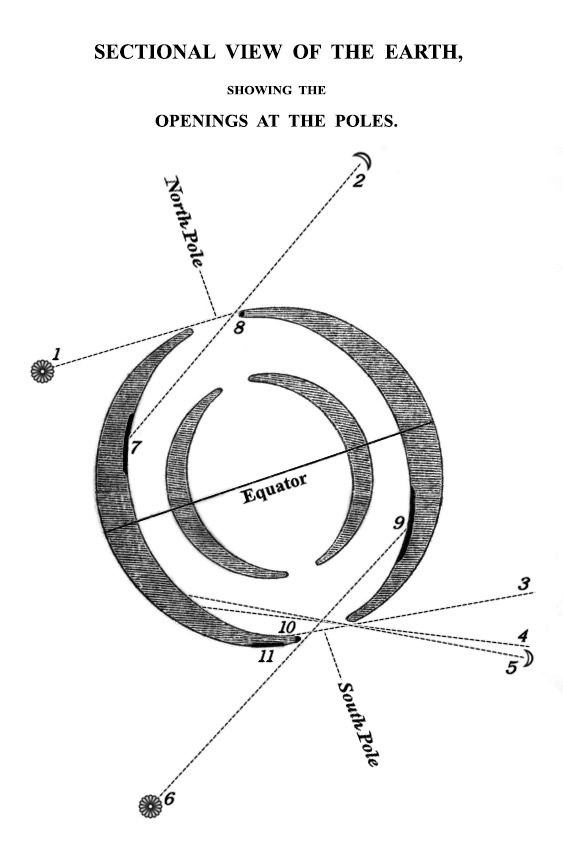

In its original form, Symmes's Hollow Earth theory described the world as consisting of fiveconcentric

In geometry, two or more objects are said to be ''concentric'' when they share the same center. Any pair of (possibly unalike) objects with well-defined centers can be concentric, including circles, spheres, regular polygons, regular polyh ...

spheres, with our outer earth and its atmosphere as the largest. He visualized the Earth's crust as being approximately 1,000 miles (1,610 km) thick, with an Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

opening about 4,000 miles (6,450 km) wide, and an Antarctic

The Antarctic (, ; commonly ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the South Pole, lying within the Antarctic Circle. It is antipodes, diametrically opposite of the Arctic region around the North Pole.

The Antar ...

opening around 6,000 miles (9,650 km) wide. Symmes proposed that the curvature of the rim of these polar openings was gradual enough that it would be possible to actually enter the inner earth without being aware of the transition. He argued that due to the centrifugal force of Earth's rotation, the Earth would be flattened at the poles, leading to a vast passage into the inner Earth. Symmes's concept of polar openings connecting the Earth's surface to the inner Earth was to be his unique contribution to Hollow Earth lore. Such polar openings would come to be known as "Symmes Holes" in literary Hollow Earths.

Symmes held that the inner surfaces of the concentric spheres in his Hollow Earth would be illuminated by sunlight reflected off of the outer surface of the next sphere down and would be habitable, being a "warm and rich land, stocked with thrifty vegetables and animals if not men". He also believed that the spheres revolved at different rates and upon different axes, and that the apparent instability of magnetic North in the Arctic could be explained by travelers moving unawares across and along the verge between the inner and outer earths.

Symmes generalized his theory beyond just the Earth, claiming that "the Earth as well as all the celestial orbicular bodies existing in the inverse, visible and invisible, which partake in any degree of a planetary nature, from the greatest to the smallest, from the sun down to the most minute blazing meteor or falling star, are all constituted, in a greater or less degree, of a collection of spheres".

Ultimately, Symmes was to simplify his theory, abandoning the series of concentric inner spheres, and teaching "only one concentric sphere (a hollow earth), not five" by the time he embarked on his lecture tour of the East Coast.

Origins of Symmes's theory

Writing in August 1817 to his stepson, Anthony Lockwood, Symmes for the first time stated that "I infer that all planets and globes are hollow". But Symmes' theory was far from unprecedented. While the idea of polar openings leading into a Hollow Earth was Symmes' innovation, the concept of a Hollow Earth had an intellectual pedigree dating back to the 17th century andEdmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, Hal ...

. Halley proposed his Hollow Earth theory as an explanation for the different locations of the geographic

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

and magnetic poles of the Earth. While Halley's contemporaries found the geomagnetic

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from structure of Earth, Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from ...

data he had gathered to be of interest, his proposal of a Hollow Earth was never widely accepted. The theory remained dear to Halley; he chose to have his final portrait (as Astronomer Royal) painted depicting him holding a drawing of the Earth's interior as a set of concentric spheres. Some scholars have proposed that Symmes may have learned of Halley's Hollow Earth via Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a Puritan clergyman and author in colonial New England, who wrote extensively on theological, historical, and scientific subjects. After being educated at Harvard College, he join ...

's book, ''The Christian Philosopher,'' a popular survey of science as natural theology

Natural theology is a type of theology that seeks to provide arguments for theological topics, such as the existence of a deity, based on human reason. It is distinguished from revealed theology, which is based on supernatural sources such as ...

.

Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler

Leonhard Euler ( ; ; ; 15 April 170718 September 1783) was a Swiss polymath who was active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, logician, geographer, and engineer. He founded the studies of graph theory and topology and made influential ...

has often been claimed as a proponent of a Hollow Earth theory. The version of the Hollow Earth theory ascribed to Euler lacked the concentric spheres of Halley's proposal, but added the element of an interior sun. But Euler may never have actually suggested any such thing; Euler scholar, C. Edward Sandifer, has examined Euler's writings and found no evidence for any such belief.

Whether or not Euler ever proposed a Hollow Earth, Symmes and some of his contemporaries certainly thought Euler had. In an 1824 exchanges of newspaper letters with Symmes, D. Preston implied that Symmes' theory was not original, and cited both Halley and Euler as earlier examples. Symmes himself insisted that he had not known of Hollow Earth proposals of Halley and Euler at the time he conceived his theory, and that he had only learned of their works much later. Symmes' disciple, James McBride, promoting and explaining Symmes' theory in his book, ''Symmes's Theory of Concentric Spheres'' (1826), cited Euler as an earlier proponent of a similar theory.

Circulars, lectures, and ''Symzonia''

For the first two years after the publication of his theory, Symmes confined his promotional efforts to circulars and letters published in newspapers and magazines. In all, he issued seven additional circulars from 1818 to 1819, including ''Light Between the Spheres,'' which gained a national audience via its publication in the ''

For the first two years after the publication of his theory, Symmes confined his promotional efforts to circulars and letters published in newspapers and magazines. In all, he issued seven additional circulars from 1818 to 1819, including ''Light Between the Spheres,'' which gained a national audience via its publication in the ''National Intelligencer

The ''National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser'' was a newspaper published in Washington, D.C., from October 30, 1800 until 1870. It was the first newspaper published in the District, which was founded in 1790. It was originally a tri ...

.'' But though Symmes made converts, his theory continued to be greeted with general ridicule.

In 1819, Symmes moved his family from St. Louis to Newport, Kentucky

Newport is a list of Kentucky cities, home rule-class city in Campbell County, Kentucky, United States. It is at the confluence of the Ohio River, Ohio and Licking River (Kentucky), Licking rivers across from Cincinnati. The population was 14,150 ...

. And in 1820, Symmes began to promote his theory directly, lecturing on it in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

and other towns and cities in the region, making use of a wooden globe with the polar sections removed to reveal the inner Earth and the spheres within. (Symmes's modified globe can now be found in the collection of Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University

The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, formerly the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, is the oldest natural science research institution and museum in the Americas. It was founded in 1812, by many of the leading natur ...

.) Symmes was not a commanding lecturer; he was uncomfortable as a public speaker, hesitant in speaking, and possessed a nasal voice. Still, he persevered.

Symmes began to make converts and his ideas began to filter into the public consciousness, and popular support for his proposed Arctic expedition started to build. In 1820, he sat for a never-completed portrait by artist John J. Audubon for Cincinnati's Western Museum. Audubon wrote on the back of the sketch, "John, Cleeves Simms—The man with the hole at the Pole—Drawn and a good likeness it is".

Some have claimed he was the real author of: ''Symzonia; Voyage of Discovery'', which was attributed to "Captain Adam Seaborn". A recent reprint gives him as the author. Other researchers argue against this idea. Some think it was written as a satire of Symmes's ideas, and believe they identified the author as early American writer Nathaniel Ames.

McBride and Reynolds—the disciples

Symmes himself never wrote a book of his ideas, as he was too busy expounding them on the lecture circuit, but others did. His follower James McBride wrote and published ''Symmes' Theory of Concentric Spheres'' in 1826. Another follower, Jeremiah N. Reynolds apparently had an article that was published as a separate booklet in 1827: ''Remarks of Symmes' Theory Which Appeared in the American Quarterly Review''. In 1868 a professor W.F. Lyons published ''The Hollow Globe'' which put forth a Symmes-like Hollow Earth theory, but did not mention Symmes. Symmes's son Americus then republished ''The Symmes' Theory of Concentric Spheres'' to set the record straight.Legacy

Americus Symmes

Symmes's death left his eldest son, seventeen-year-old Americus Symmes, the sole support of the family, with an estate significantly in debt. Americus provided for his mother and siblings and paid off his father's debts. He also championed his father's legacy, erecting a memorial to him (a pylon topped with a globe carved in the shape of a hollow sphere) and publishing in 1878 an edited collection of his father's papers, ''Symmes's Theory of Concentric Spheres: Demonstrating That the Earth is Hollow, Habitable Within, and Widely Open About the Poles, Compiled by Americus Symmes, from the Writings of his Father, Capt. John Cleves Symmes'' (not to be confused with the book of a very similar title published by James McBride in 1826).Literary

Edgar Allen Poe's' short story "MS. Found in a Bottle" (1833), which describes a ship driven toward the South Pole by a storm and consumed by a whirlpool there, may have been inspired by Symmes' assertions, or have been intended as a satire of ''Symzonia'' itself. Symmes features as the source of information about the hollow Earth used as a literary trope in Grigsby, Alcanoan O and Mary P. Lowe's "Nequa, or The Problem of the Ages" (1900). Compare a fictional echo of Symmes in Ian Wedde's ''Symmes Hole'' (1987); and a focus on both Symmes and Reynolds in James Chapman's ''Our Plague: A Film From New York'' (1993). Symmes' work is referenced inVladimir Obruchev

Vladimir Afanasyevich Obruchev (; – June 19, 1956) was a Russian and Soviet geologist who specialized in the study of Siberia and Central Asia. He was also one of the first Russian science fiction authors.

Scientific research

Vladimir Obr ...

's 1915 novel Plutonia (novel).

John Cleves Symmes also makes an appearance in Rudy Rucker

Rudolf von Bitter Rucker (; born March 22, 1946) is an American mathematician, computer scientist, science fiction author, and one of the founders of the cyberpunk literary movement. The author of both fiction and non-fiction, he is best known f ...

's steampunk novel, ''The Hollow Earth'', and in Felix J. Palma's ''The Map of the Sky''.

Samuel Highgate Syme, the subject of '' The Syme Papers'' in Benjamin Markovits's book of the same name, is based on John Cleves Symmes.

References

External links

* John Cleves Symmes, Captain''Circular No. 1''

(St. Louis, MO: Privately Publibout the Poles, Compiled by Americus Symmes, from the Writings of his Father, Capt. John Cleves Symmes, 1780–1829.] (Louisville, KY: Bradley & Gilbert, 1878) {{DEFAULTSORT:Symmes, John Cleves Jr. 1779 births 1829 deaths Military personnel from New Jersey Academics from New Jersey Hollow Earth proponents United States Army officers United States Army personnel of the War of 1812 Military personnel from Sussex County, New Jersey