John Brown's Raiders on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

On Sunday night, October 16, 1859, the

‡ Jeremiah Goldsmith Anderson, 26, born in Indiana, served with Brown in Kansas. Brown was "attended, generally, in his movements about the city ostonand its neighborhood, by a faithful henchman, Jerry Anderson." He was killed by a Marine's bayonet during the final assault on the engine house. He had in his pocket a letter from his brother John J. (or G. or Q.) Anderson, of

‡ Jeremiah Goldsmith Anderson, 26, born in Indiana, served with Brown in Kansas. Brown was "attended, generally, in his movements about the city ostonand its neighborhood, by a faithful henchman, Jerry Anderson." He was killed by a Marine's bayonet during the final assault on the engine house. He had in his pocket a letter from his brother John J. (or G. or Q.) Anderson, of  † Oliver Brown, 20, John Brown's son, served in Kansas, and he was mortally wounded during the raid Oliver, the youngest of John Brown's three sons to participate in the action. He was described by his mother as the child "most like his father, caring most for learning of all our children." He was mortally wounded on the 17th inside the engine house, and died beside his father. First buried in one of two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba.

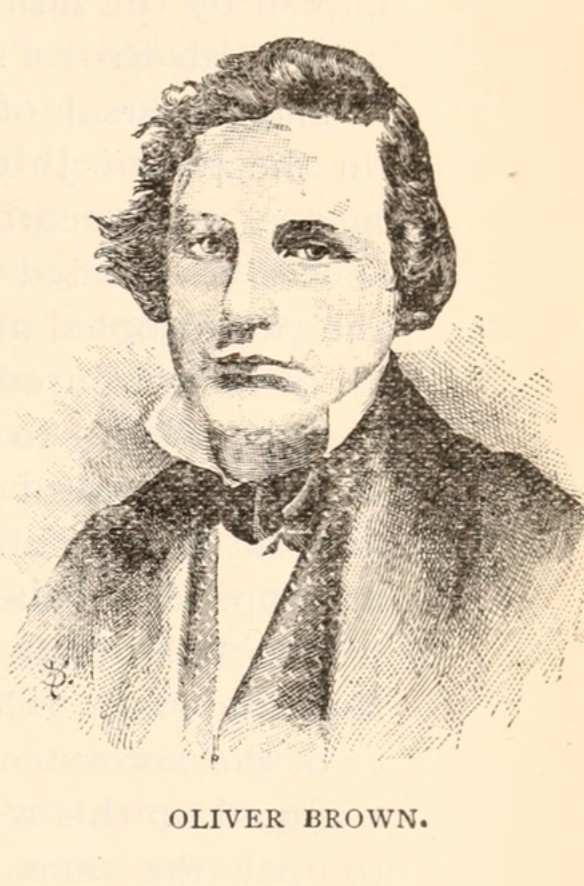

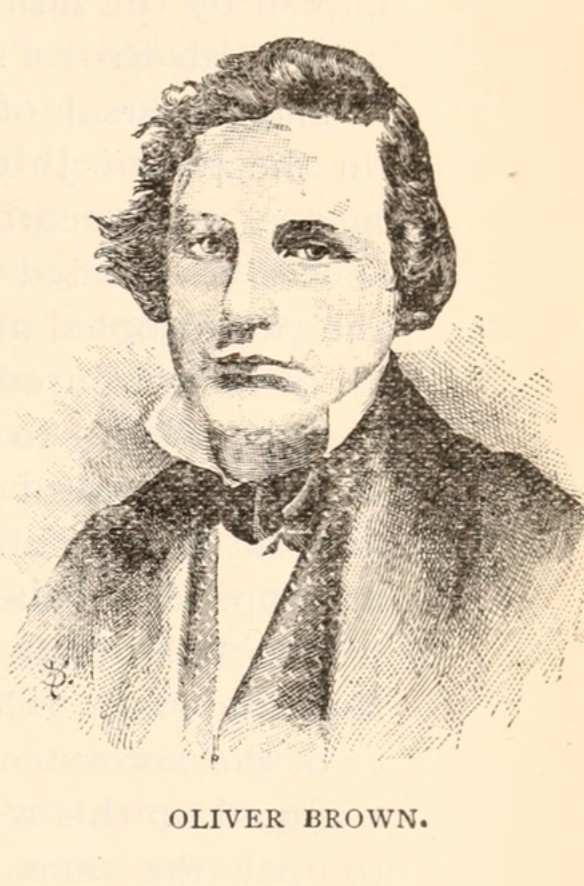

† Oliver Brown, 20, John Brown's son, served in Kansas, and he was mortally wounded during the raid Oliver, the youngest of John Brown's three sons to participate in the action. He was described by his mother as the child "most like his father, caring most for learning of all our children." He was mortally wounded on the 17th inside the engine house, and died beside his father. First buried in one of two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba.

Owen Brown, about 35, John Brown's son, fought in Kansas. He escaped the raid. Owen, one of three of Brown's sons to participate in the raid, was the last surviving raider following the death of Osborn P. Anderson in 1873. He died in 1889

Owen Brown, about 35, John Brown's son, fought in Kansas. He escaped the raid. Owen, one of three of Brown's sons to participate in the raid, was the last surviving raider following the death of Osborn P. Anderson in 1873. He died in 1889

John Edwin Cook, 29, reformer and former soldier, attended

John Edwin Cook, 29, reformer and former soldier, attended

†

†  † William H. Leeman, 20, fought with the free-staters in Kansas for three years, beginning at the age of 17. He died during the raid. Leeman, from Maine, youngest of all the raiders, was shot and killed while trying to escape across the Potomac River. His sister, Mrs. S. H. Brown, published a letter of John Brown of November 28, 1859, which according to her had never been published. From it we learn he was killed not trying to escape, but trying to deliver a message of John Brown to Owen Brown or Cook. He was reburied at the John Brown burial grounds.

† William H. Leeman, 20, fought with the free-staters in Kansas for three years, beginning at the age of 17. He died during the raid. Leeman, from Maine, youngest of all the raiders, was shot and killed while trying to escape across the Potomac River. His sister, Mrs. S. H. Brown, published a letter of John Brown of November 28, 1859, which according to her had never been published. From it we learn he was killed not trying to escape, but trying to deliver a message of John Brown to Owen Brown or Cook. He was reburied at the John Brown burial grounds.

Charles Plummer Tidd, 25, fought in Kansas. He escaped the raid and later served during the Civil War. as a 1st Sgt; died 8 Feb 1862 Buried Unknown grave New Bern National Cemetery North Carolina

Charles Plummer Tidd, 25, fought in Kansas. He escaped the raid and later served during the Civil War. as a 1st Sgt; died 8 Feb 1862 Buried Unknown grave New Bern National Cemetery North Carolina

¶

¶  ‡ Watson Brown, 24, son of John Brown, mortally wounded during the raid Watson was mortally wounded outside the engine house while carrying a white flag to negotiate with the opposing militia. He was not shot by a Marine, as they respected the white flag, but by an infuriated townsman. He survived in agony for another day. His body was taken by Winchester Medical College, skinned, and preserved as an anatomical specimen. When a Union army occupied Winchester in 1862, his body was "rescued" by a Union doctor, who had it shipped to his home in Indiana. It was returned to the family and buried in North Elba in 1882. See

‡ Watson Brown, 24, son of John Brown, mortally wounded during the raid Watson was mortally wounded outside the engine house while carrying a white flag to negotiate with the opposing militia. He was not shot by a Marine, as they respected the white flag, but by an infuriated townsman. He survived in agony for another day. His body was taken by Winchester Medical College, skinned, and preserved as an anatomical specimen. When a Union army occupied Winchester in 1862, his body was "rescued" by a Union doctor, who had it shipped to his home in Indiana. It was returned to the family and buried in North Elba in 1882. See  ¶

¶

Edwin Coppock, 24, he was captured and executed by hanging, December 16, 1859. Buried Hope Cemetery, Salem, Columbiana County Ohio

Edwin Coppock, 24, he was captured and executed by hanging, December 16, 1859. Buried Hope Cemetery, Salem, Columbiana County Ohio

¶

¶  † ¶

† ¶  † ¶ Dangerfield Newby, 35 or 44, was born into slavery, with a white father who was not his owner. He was given permission to move to Ohio along with his mother and siblings, but when he tried to gain freedom for his wife and children, their owner refused to sell them even after Newby had earned and saved the agreed-upon price. This inspired Newby return to Virginia to join Brown's raid. Newby was described as a "huge mulatto", He was the first raider killed. His body was mutilated: his ears and genitals were cut off as souvenirs. An excerpt, "When Robert E. Lee Met John Brown and Saved the Union", wa

† ¶ Dangerfield Newby, 35 or 44, was born into slavery, with a white father who was not his owner. He was given permission to move to Ohio along with his mother and siblings, but when he tried to gain freedom for his wife and children, their owner refused to sell them even after Newby had earned and saved the agreed-upon price. This inspired Newby return to Virginia to join Brown's raid. Newby was described as a "huge mulatto", He was the first raider killed. His body was mutilated: his ears and genitals were cut off as souvenirs. An excerpt, "When Robert E. Lee Met John Brown and Saved the Union", wa

published

in † Dauphin Thompson, 21, married to Ruth Brown, John Brown's daughter, mortally wounded during the raid From North Elba, New York, he was killed in the storming of the engine house. He was brother of William. First buried in one of two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba.

† William Thompson, 26, mortally wounded during the raid William Thompson, from North Elba, New York, was brother of Adolphus. They were brothers of Henry Thompson, who was married to Ruth, John Brown's eldest daughter. First buried in one of two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba.

† Dauphin Thompson, 21, married to Ruth Brown, John Brown's daughter, mortally wounded during the raid From North Elba, New York, he was killed in the storming of the engine house. He was brother of William. First buried in one of two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba.

† William Thompson, 26, mortally wounded during the raid William Thompson, from North Elba, New York, was brother of Adolphus. They were brothers of Henry Thompson, who was married to Ruth, John Brown's eldest daughter. First buried in one of two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba.

In the short term, the raid was a total failure. Brown and his men quickly captured the armory, which had only one watchman, and took over 60 residents of Harpers Ferry hostage as they arrived for work. Militia summoned from neighboring towns took over both bridges, thus cutting off escape, and by noon Monday forced Brown and his party to take refuge in the fire engine house of the armory, a sturdy building later known as

In the short term, the raid was a total failure. Brown and his men quickly captured the armory, which had only one watchman, and took over 60 residents of Harpers Ferry hostage as they arrived for work. Militia summoned from neighboring towns took over both bridges, thus cutting off escape, and by noon Monday forced Brown and his party to take refuge in the fire engine house of the armory, a sturdy building later known as

/ref> Historians frequently credit the raid not for starting the

In the Charles Town jail, by one report, Brown and Hazlett shared a room and a bed, Green and Coppock another, manacled together, and Copeland was in a third room. The rooms in the jail were described as "very large and nicely kept".

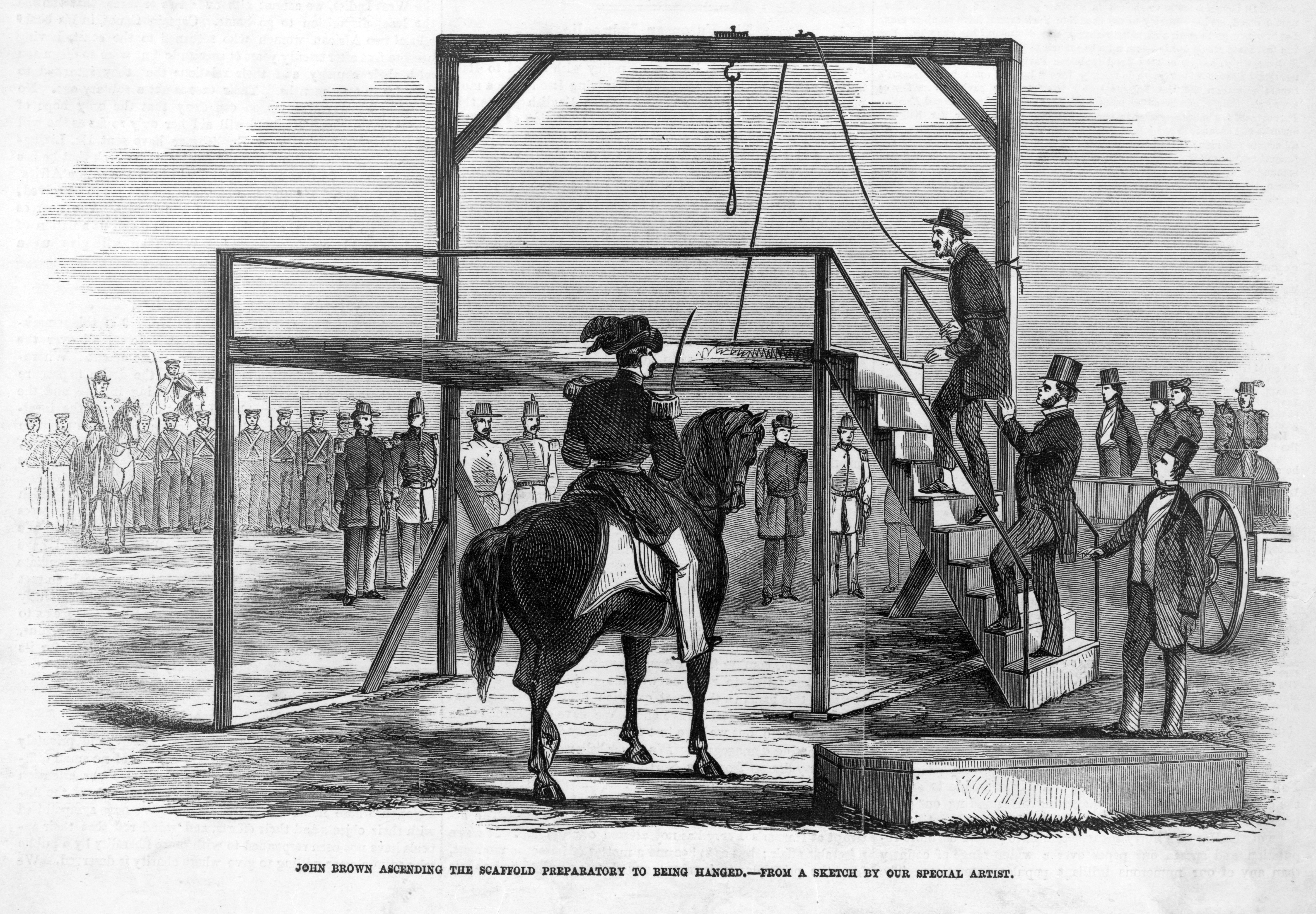

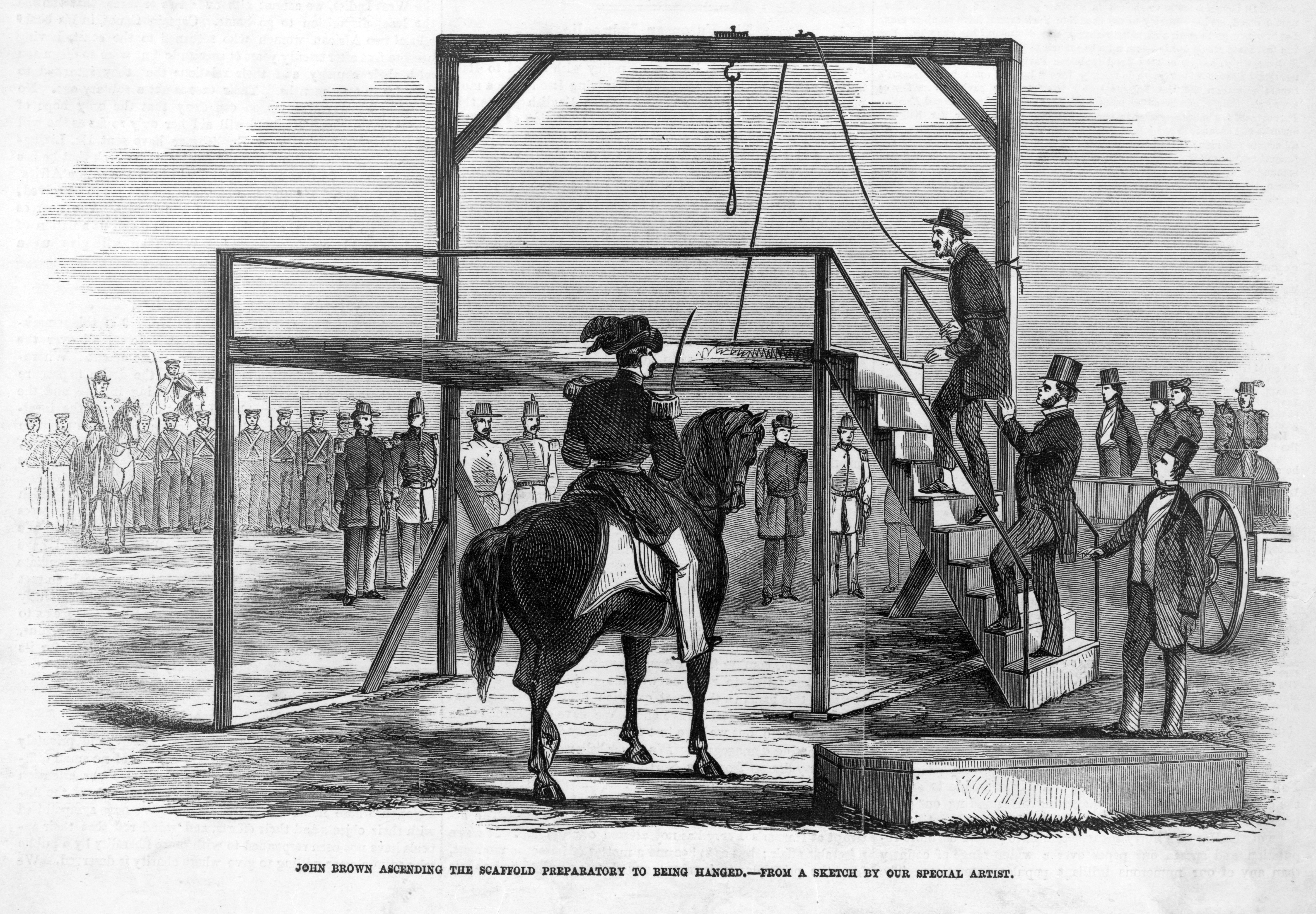

Brown was executed on Friday, December 2, four others on December 16, 1859, the negroes (Copeland, Green) in the morning and the whites (Cook, Coppock) in the afternoon, and two (Hazlitt, Stevens) on March 16, 1860. Cook and Coppock attempted to escape, but did not get over the jail wall.

To prevent a rescue, spectators at Brown's execution were very limited. (See .) In contrast, Governor Wise wanted there to be a "tremendous" crowd for the December 16 hangings, and the Sheriff so informed the newspapers. "The execution was witnessed by an immense throng." There was a dress parade; among the participants was Lt. Israel Green of the U.S. Marines, the one who led the assault on

In the Charles Town jail, by one report, Brown and Hazlett shared a room and a bed, Green and Coppock another, manacled together, and Copeland was in a third room. The rooms in the jail were described as "very large and nicely kept".

Brown was executed on Friday, December 2, four others on December 16, 1859, the negroes (Copeland, Green) in the morning and the whites (Cook, Coppock) in the afternoon, and two (Hazlitt, Stevens) on March 16, 1860. Cook and Coppock attempted to escape, but did not get over the jail wall.

To prevent a rescue, spectators at Brown's execution were very limited. (See .) In contrast, Governor Wise wanted there to be a "tremendous" crowd for the December 16 hangings, and the Sheriff so informed the newspapers. "The execution was witnessed by an immense throng." There was a dress parade; among the participants was Lt. Israel Green of the U.S. Marines, the one who led the assault on

Tomb of eight killed in Harpers Ferry.jpg, Spot where crates with bodies of Oliver Brown and seven others were buried.

Reburial at John Brown's farm, 1899.jpg, Rev.

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

led a band of 22 in a raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (since 1863, West Virginia).

Composition of the group

The group of men varied in social class and education. They had come from all over the country and Canada, and were from diverse social classes, fromfugitive slaves

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th centuries to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called fre ...

to the upper middle class. John Brown was 59, Dangerfield Newby was 44, and Owen Brown was 35. All the rest were under 30. Oliver Brown, Barclay Coppoc, and William H. Leeman were under 21.

Of the members of Brown's party, 17 were white and 5 (23%) were Black. Of the five black people, two ( Leary, Newby) died during the raid, two ( Copeland and Green

Green is the color between cyan and yellow on the visible spectrum. It is evoked by light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 495570 nm. In subtractive color systems, used in painting and color printing, it is created by a com ...

) were tried and executed, and one ( Osborne Anderson) escaped. Two (Green and Newby) had been enslaved, with Newby having been granted his freedom and Green a fugitive

A fugitive or runaway is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also known ...

; three (Osborne Anderson, Copeland, and Leary) were free black people, but Copeland was a fugitive from the charge of participating in the 1858 Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, of which he was a leader.

Three of Brown's sons participated in the raid. Two, Oliver and Watson, were shot on Monday at the engine house; Oliver died after a few hours in agony, but Watson not until early Wednesday morning. Owen Brown escaped and became an officer in the Union Army. Watson's body was recovered in 1882; Oliver's not until 1899. Salmon Brown, though he had been with his father and brothers in Kansas, did not want to participate in the Harpers Ferry raid and remained in North Elba, running the farm. John Jr. and Jason also declined to participate.

All but 5, who successfully escaped north, were either killed during the raid, or captured, tried, and executed. Of the 22,

*10 were killed during the raid or died shortly after of their wounds (Jerry Anderson, Oliver Brown, Watson Brown, Kagi, Leary, Leeman, Newby, Taylor, Adolphus Thompson, William Thompson)

*7 were tried and executed, 5 who were taken prisoner on the spot (John Brown, Cook, Copeland, Edwin Coppock, Green) plus 2 who escaped but were captured (Hazlitt, Stevens)

*5 escaped north and were not captured (Osborne Anderson, Owen Brown, Barclay Coppock, Meriam, Tidd).

Raiders

The men who participated in the raid are made up of two groups, depending whether or not they fought with Brown in Kansas. As of 2012, there had never been a book on any of Brown's raiders. Three appeared in quick succession: 2012 on John E. Cook, 2015 on John Anthony Copeland, and in 2020 onShields Green

Shields Green (1836? – December 16, 1859), who also referred to himself as "Emperor", was, according to Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave from Charleston, South Carolina, and a leader in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, in October 1859. He ...

, plus a 2018 book on Brown's five Black raiders, ''Five for Freedom: the African American Soldiers in John Brown's Army''.

Fought with Brown in Kansas

A group that fought with him in Kansas and gathered at Springdale,Iowa

Iowa ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the upper Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west; Wisconsin to the northeast, Ill ...

, to prepare and drill for the raid,

‡ Jeremiah Goldsmith Anderson, 26, born in Indiana, served with Brown in Kansas. Brown was "attended, generally, in his movements about the city ostonand its neighborhood, by a faithful henchman, Jerry Anderson." He was killed by a Marine's bayonet during the final assault on the engine house. He had in his pocket a letter from his brother John J. (or G. or Q.) Anderson, of

‡ Jeremiah Goldsmith Anderson, 26, born in Indiana, served with Brown in Kansas. Brown was "attended, generally, in his movements about the city ostonand its neighborhood, by a faithful henchman, Jerry Anderson." He was killed by a Marine's bayonet during the final assault on the engine house. He had in his pocket a letter from his brother John J. (or G. or Q.) Anderson, of Chillicothe, Ohio

Chillicothe ( ) is a city in Ross County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. The population was 22,059 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located along the Scioto River 45 miles (72 km) south of Columbus, Ohio, Columbus, ...

. His body was taken by Winchester Medical College; last resting place unknown.

† Oliver Brown, 20, John Brown's son, served in Kansas, and he was mortally wounded during the raid Oliver, the youngest of John Brown's three sons to participate in the action. He was described by his mother as the child "most like his father, caring most for learning of all our children." He was mortally wounded on the 17th inside the engine house, and died beside his father. First buried in one of two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba.

† Oliver Brown, 20, John Brown's son, served in Kansas, and he was mortally wounded during the raid Oliver, the youngest of John Brown's three sons to participate in the action. He was described by his mother as the child "most like his father, caring most for learning of all our children." He was mortally wounded on the 17th inside the engine house, and died beside his father. First buried in one of two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba.

Owen Brown, about 35, John Brown's son, fought in Kansas. He escaped the raid. Owen, one of three of Brown's sons to participate in the raid, was the last surviving raider following the death of Osborn P. Anderson in 1873. He died in 1889

Owen Brown, about 35, John Brown's son, fought in Kansas. He escaped the raid. Owen, one of three of Brown's sons to participate in the raid, was the last surviving raider following the death of Osborn P. Anderson in 1873. He died in 1889

John Edwin Cook, 29, reformer and former soldier, attended

John Edwin Cook, 29, reformer and former soldier, attended Oberlin College

Oberlin College is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college and conservatory of music in Oberlin, Ohio, United States. Founded in 1833, it is the oldest Mixed-sex education, coeducational lib ...

, he initially escaped capture, but was found and hanged 16 December 1859. The book, ''John Brown's Spy. The Adventurous Life and Tragic Confession of John E. Cook'', was written about him and published in 2012. Buried Green-wood Cemetery, Brooklyn New York

Albert Hazlett

Albert Hazlett (c. 1836 – March 16, 1860; né Absalom Hazlett) was an American abolitionist, and participant in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry (October 16 to 18, 1859). He was executed on March 16, 1860, in Charles Town, Virginia, (now in ...

, 23, fought in Kansas, escaped following the raid, but was captured and hanged. 16 March 1860. Buried John Brown Burial grounds

†

† John Henry Kagi

John Henry Kagi, also spelled John Henri Kagi (March 15, 1835 – October 17, 1859), was an American attorney, abolitionist, and second in command to John Brown in Brown's failed raid on Harper's Ferry. He bore the title of "Secretary of War" ...

, about 24, a teacher from Ohio, became Brown's second in command, before the raid he printed copies of Brown's constitution in a printing shop he established in Hamilton, Ontario

Hamilton is a port city in the Canadian Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Ontario. Hamilton has a 2021 Canadian census, population of 569,353 (2021), and its Census Metropolitan Area, census metropolitan area, which encompasses ...

, mortally wounded during the raid He was shot and killed while attempting to cross the Shenandoah River. One report says mistakenly that his body was taken for dissection. First buried in one of two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba.

† William H. Leeman, 20, fought with the free-staters in Kansas for three years, beginning at the age of 17. He died during the raid. Leeman, from Maine, youngest of all the raiders, was shot and killed while trying to escape across the Potomac River. His sister, Mrs. S. H. Brown, published a letter of John Brown of November 28, 1859, which according to her had never been published. From it we learn he was killed not trying to escape, but trying to deliver a message of John Brown to Owen Brown or Cook. He was reburied at the John Brown burial grounds.

† William H. Leeman, 20, fought with the free-staters in Kansas for three years, beginning at the age of 17. He died during the raid. Leeman, from Maine, youngest of all the raiders, was shot and killed while trying to escape across the Potomac River. His sister, Mrs. S. H. Brown, published a letter of John Brown of November 28, 1859, which according to her had never been published. From it we learn he was killed not trying to escape, but trying to deliver a message of John Brown to Owen Brown or Cook. He was reburied at the John Brown burial grounds.

Aaron Dwight Stevens

Aaron Dwight Stevens (sometimes misspelled Stephens) (March 15, 1831 – March 16, 1860) was an American abolitionist. The only one of John Brown's raiders with military experience, he was the chief military aide to Brown during his failed ...

, about 28, was a former soldier and fighter in Kansas, who gave the men military training and drills. He was wounded during the raid, after which he was executed. 16 March 1860Buried John Brown Burial grounds

Charles Plummer Tidd, 25, fought in Kansas. He escaped the raid and later served during the Civil War. as a 1st Sgt; died 8 Feb 1862 Buried Unknown grave New Bern National Cemetery North Carolina

Charles Plummer Tidd, 25, fought in Kansas. He escaped the raid and later served during the Civil War. as a 1st Sgt; died 8 Feb 1862 Buried Unknown grave New Bern National Cemetery North Carolina

Recruits

Men recruited for the raid are, ¶

¶ Osborne Perry Anderson

Osborne Perry Anderson (July 27, 1830 – December 11, 1872) was an African-American abolitionist and the only surviving African-American member of John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry. He became a soldier in the Union Army during the American Civ ...

escaped capture following the raid. He died in 1873. He is both the only Black escapee and the only escapee that had been in the engine house. He is also the only raider to publish a memoir about the raid. He served as a recruiter for the Union Army, and died in poverty in 1872. He is buried unknown grave National Harmony Cemetery Park Cemetery, Hyattsville Maryland

‡ Watson Brown, 24, son of John Brown, mortally wounded during the raid Watson was mortally wounded outside the engine house while carrying a white flag to negotiate with the opposing militia. He was not shot by a Marine, as they respected the white flag, but by an infuriated townsman. He survived in agony for another day. His body was taken by Winchester Medical College, skinned, and preserved as an anatomical specimen. When a Union army occupied Winchester in 1862, his body was "rescued" by a Union doctor, who had it shipped to his home in Indiana. It was returned to the family and buried in North Elba in 1882. See

‡ Watson Brown, 24, son of John Brown, mortally wounded during the raid Watson was mortally wounded outside the engine house while carrying a white flag to negotiate with the opposing militia. He was not shot by a Marine, as they respected the white flag, but by an infuriated townsman. He survived in agony for another day. His body was taken by Winchester Medical College, skinned, and preserved as an anatomical specimen. When a Union army occupied Winchester in 1862, his body was "rescued" by a Union doctor, who had it shipped to his home in Indiana. It was returned to the family and buried in North Elba in 1882. See Burning of Winchester Medical College

The Winchester Medical College (WMC) building, currently located at 302 W. Boscawen Street, Winchester, Virginia, along with all its records, equipment, museum, and library, was burned on May 16, 1862, by Union troops occupying the city. This was ...

.

¶

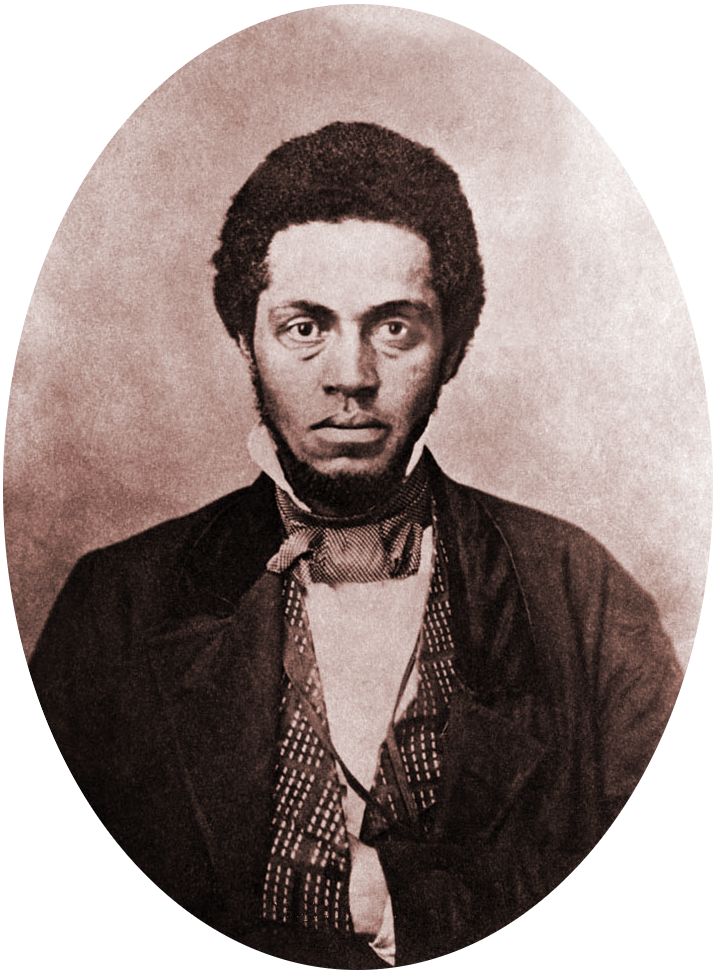

¶ John Anthony Copeland Jr.

John Anthony Copeland Jr. (August 15, 1834 – December 16, 1859) was born free in Raleigh, North Carolina, one of the eight children born to John Copeland Sr. and his wife Delilah Evans, free mulattos, who married in Raleigh in 1831. Delilah was ...

was a free black man who joined John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry. He was captured during the raid and was executed16 December 1859. The book, ''The "Colored Hero" of Harpers Ferry: John Anthony Copeland and the War against Slavery'', was published in 2015. There is a cenotaph memorial in Oberlin, Ohio.

Barclay Coppock

Barclay Coppock (January 4, 1839 – September 4, 1861), also spelled "Coppac", "Coppic", and "Coppoc", was a follower of John Brown (abolitionist), John Brown and a Union Army soldier in the American Civil War. Along with his brother Edwin ...

, 19, escaped capture following the raid. He returned to Iowa in 1860 where he was allowed to escape to Canada due to Governor Samuel Kirkwood

Samuel Jordan Kirkwood (December 20, 1813 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician who twice served as List of governors of Iowa, governor of Iowa, twice as a United States, U.S. Senator from Iowa, and as the U.S. Secretary of the Interi ...

delaying Virginia's attempt to extradite him. Coppock then traveled to Ohio and later fought in the Civil War. He was killed on September 4, 1861, in a train crash caused by bushwackers; buried Mount Aurora Cemetery, Leavenworth. Kansas

Edwin Coppock, 24, he was captured and executed by hanging, December 16, 1859. Buried Hope Cemetery, Salem, Columbiana County Ohio

Edwin Coppock, 24, he was captured and executed by hanging, December 16, 1859. Buried Hope Cemetery, Salem, Columbiana County Ohio

¶

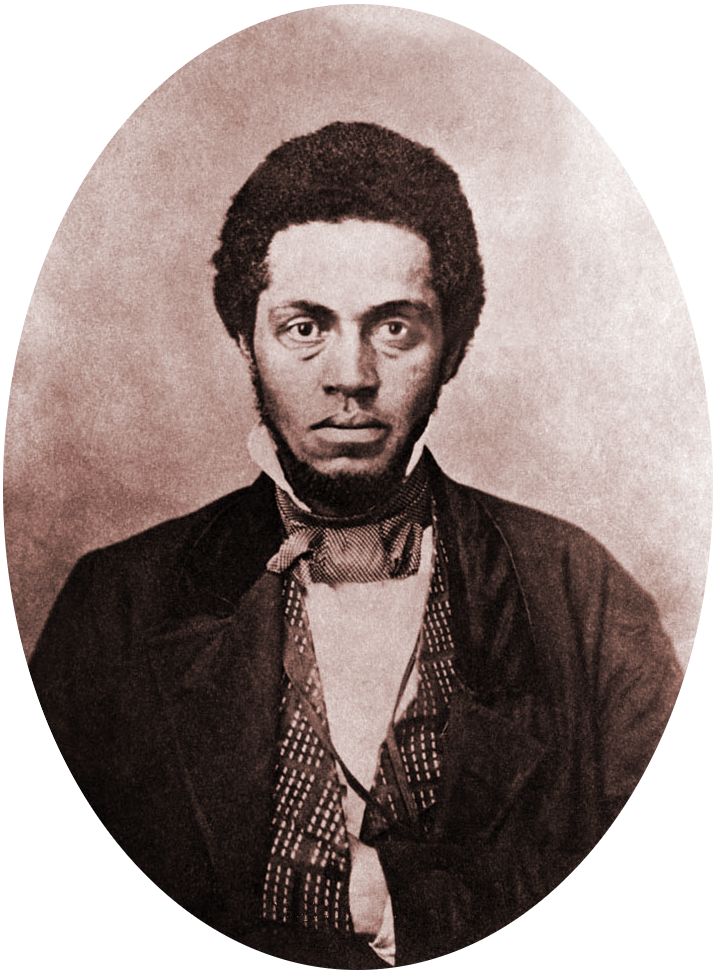

¶ Shields Green

Shields Green (1836? – December 16, 1859), who also referred to himself as "Emperor", was, according to Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave from Charleston, South Carolina, and a leader in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, in October 1859. He ...

, about 23, escaped slavery, captured and hanged on 16 December 1859. The book about him, entitled ''The Untold Story of Shields Green'', was published in 2020. There is a cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty grave, tomb or a monument erected in honor of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere or have been lost. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although t ...

memorial in Oberlin, Ohio

Oberlin () is a city in Lorain County, Ohio, United States. It is located about southwest of Cleveland within the Cleveland metropolitan area. The population was 8,555 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Oberlin is the home of Oberlin ...

.

† ¶

† ¶ Lewis Sheridan Leary

Lewis Sheridan Leary (March 17, 1835 – October 20, 1859) was an African-American harnessmaker from Oberlin, Ohio, who joined John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, where he was killed.

Life

Leary's father was a free born African-American har ...

, 24, was freed by his white father and was harness maker. Leary was from Oberlin, Ohio

Oberlin () is a city in Lorain County, Ohio, United States. It is located about southwest of Cleveland within the Cleveland metropolitan area. The population was 8,555 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Oberlin is the home of Oberlin ...

. "He said before he died that he enlisted with Capt. Brown for the insurrection at a fair held in Lorraine County, Ohio, and received the money to pay his expenses." He was stationed in the rifle factory with Kagi. He was mortally wounded while trying to escape across the Shenandoah River

The Shenandoah River is the principal tributary of the Potomac River, long with two River fork, forks approximately long each,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed August ...

. John Anthony Copeland was his nephew and Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1901 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. An early innovator of jazz poetry, Hughes is best known as a leader of the Harl ...

was his grandson. There is a cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty grave, tomb or a monument erected in honor of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere or have been lost. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although t ...

memorial in Oberlin, Ohio

Oberlin () is a city in Lorain County, Ohio, United States. It is located about southwest of Cleveland within the Cleveland metropolitan area. The population was 8,555 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Oberlin is the home of Oberlin ...

.

Francis Jackson Meriam

Francis Jackson Meriam (sometimes misspelled Merriam) was an American abolitionist, born on November 17, 1837, in Framingham, Massachusetts, Framingham, Massachusetts, and died on November 28, 1865, in New York City. He was named for his grandfath ...

, 22, grandson of Francis Jackson who was a leader of Antislavery Societies. Meriam was an aristocrat. He escaped during the raid. Captain Meriam led an African American infantry group during the Civil War. Died 28 November 1865; New York County

† ¶ Dangerfield Newby, 35 or 44, was born into slavery, with a white father who was not his owner. He was given permission to move to Ohio along with his mother and siblings, but when he tried to gain freedom for his wife and children, their owner refused to sell them even after Newby had earned and saved the agreed-upon price. This inspired Newby return to Virginia to join Brown's raid. Newby was described as a "huge mulatto", He was the first raider killed. His body was mutilated: his ears and genitals were cut off as souvenirs. An excerpt, "When Robert E. Lee Met John Brown and Saved the Union", wa

† ¶ Dangerfield Newby, 35 or 44, was born into slavery, with a white father who was not his owner. He was given permission to move to Ohio along with his mother and siblings, but when he tried to gain freedom for his wife and children, their owner refused to sell them even after Newby had earned and saved the agreed-upon price. This inspired Newby return to Virginia to join Brown's raid. Newby was described as a "huge mulatto", He was the first raider killed. His body was mutilated: his ears and genitals were cut off as souvenirs. An excerpt, "When Robert E. Lee Met John Brown and Saved the Union", wapublished

in

The Daily Beast

''The Daily Beast'' is an American news website focused on politics, media, and pop culture. Founded in 2008, the website is owned by IAC Inc.

It has been characterized as a "high-end tabloid" by Noah Shachtman, the site's editor-in-chief ...

. He carried a letter from his wife in his pocket. There is a cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty grave, tomb or a monument erected in honor of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere or have been lost. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although t ...

memorial in Oberlin, Ohio

Oberlin () is a city in Lorain County, Ohio, United States. It is located about southwest of Cleveland within the Cleveland metropolitan area. The population was 8,555 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Oberlin is the home of Oberlin ...

.

† Stewart Taylor, 22 or 23, he was a wagonmaker from Uxbridge, Ontario

Uxbridge is a township in the Regional Municipality of Durham in south-central Ontario, Canada.

Communities

The main centre in the township is the namesake community of Uxbridge. Other settlements within the township include the following: ...

, Canada, who attended the Chatham convention. According to Brown's daughter Annie, "He was more what might be called a crank than any of the party. ...He became strongly imbued with the idea that he would be one of the first killed in the coming encounter, but this fixed belief did not cause the slightest shrinking on his part."

Reburied at the John Brown farm.

† Dauphin Thompson, 21, married to Ruth Brown, John Brown's daughter, mortally wounded during the raid From North Elba, New York, he was killed in the storming of the engine house. He was brother of William. First buried in one of two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba.

† William Thompson, 26, mortally wounded during the raid William Thompson, from North Elba, New York, was brother of Adolphus. They were brothers of Henry Thompson, who was married to Ruth, John Brown's eldest daughter. First buried in one of two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba.

† Dauphin Thompson, 21, married to Ruth Brown, John Brown's daughter, mortally wounded during the raid From North Elba, New York, he was killed in the storming of the engine house. He was brother of William. First buried in one of two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba.

† William Thompson, 26, mortally wounded during the raid William Thompson, from North Elba, New York, was brother of Adolphus. They were brothers of Henry Thompson, who was married to Ruth, John Brown's eldest daughter. First buried in one of two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba.

Joined the group in Harpers Ferry

¶ Jim was freed by Brown's men from Lewis Washington. According to Osborne Anderson, Jim fought "like a tiger". He was killed while trying to escape, which must have meant attempting to swim the river, and his body was presumably carried away downstream. The disposition of his body is unknown. ¶ Ben (Allstadt), freed by Brown's men from his owner, John Allstadt. His mother Ary, also belonging to Allstadt, came to the jail to nurse him and also died there.Leading up to the raid

In June, Brown paid his last visit to his family in North Elba before departing for Harpers Ferry. He stayed one night en route inHagerstown, Maryland

Hagerstown is a city in Washington County, Maryland, United States, and its county seat. The population was 43,527 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Hagerstown ranks as Maryland's List of municipalities in Maryland, sixth-most popu ...

, at the Washington House, on West Washington Street. On June 30, 1859, the hotel had at least 25 guests, including I. Smith and Sons, Oliver Smith and Owen Smith, and Jeremiah Anderson, all from New York. From papers found in the Kennedy Farmhouse after the raid, it is known that Brown wrote to Kagi that he would sign into a hotel as I. Smith and Sons., whilbr.org; accessed August 29, 2015.

Kennedy farmhouse

They were at Kennedy Farmhouse, four to five miles away from Harpers Ferry. Brown's daughter and daughter-in-law, Anne (Annie) and Martha, Oliver's wife, prepared food and kept the house for the men from August and throughout the month of September. Besides their domestic activities, Anne, who was 15, and Martha, 17, "kept discreet watch over the prattling conspirators in the house and hustled them out of sight on occasion, and who turned aside local suspicion by their sweet and honest ways." Martha was pregnant. John sent them home to North Elba on September 29 or 30. Much later Annie shared her recollections. "Ever after, Annie saw her months at the Kennedy farm as the most important of her life."Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

Brown led his forces for Harper Ferry on the night of October 16, 1859. The objective was to take the armory, the arsenal, the town, and then the rifle factory. Then, they wanted to free all the slaves in Harpers Ferry. After that, they would move south with those newly freed people wanted to join the fight to free other enslaved people. Brown told his men to take prisoners who disobeyed them and to fight only in self-defense. Of Brown's party of 22, counting himself, 19 went to Harpers Ferry (Jerry Anderson, Osborne Anderson, John Brown, his sons Oliver and Watson Brown, Cook, Copeland, Edwin Coppock, Green,Hazlett Hazlett is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Allan Hazlett, American philosopher

*Bill Hazlett (1905–1978), New Zealand athlete in rugby

*Charles E. Hazlett (1838–1863), U.S. Army officer, Union artillery commander killed at t ...

, Kagi, Leary, Leeman, Newby, Stevens, Taylor, brothers Adolphus and William Thompson, Tidd). Three men—Owen Brown, Barclay Coppock, Meriam—remained at the Kennedy Farm

The Kennedy Farm is a National Historic Landmark property on Chestnut Grove Road in rural southern Washington County, Maryland. It is notable as the place where the radical abolitionist John Brown planned and began his raid on Harpers Ferry, ...

in Maryland, "to guard the arms and ammunition stored on the premises, until it should be time to move them."

In the short term, the raid was a total failure. Brown and his men quickly captured the armory, which had only one watchman, and took over 60 residents of Harpers Ferry hostage as they arrived for work. Militia summoned from neighboring towns took over both bridges, thus cutting off escape, and by noon Monday forced Brown and his party to take refuge in the fire engine house of the armory, a sturdy building later known as

In the short term, the raid was a total failure. Brown and his men quickly captured the armory, which had only one watchman, and took over 60 residents of Harpers Ferry hostage as they arrived for work. Militia summoned from neighboring towns took over both bridges, thus cutting off escape, and by noon Monday forced Brown and his party to take refuge in the fire engine house of the armory, a sturdy building later known as John Brown's Fort

John Brown's Fort was initially built in 1848 for use as a guard and fire engine house by the federal Harpers Ferry Armory, in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, Harpers Ferry, Virginia (since 1863, West Virginia). An 1848 military report described ...

. The militia freed most of the hostages, leaving only the handful in the engine house. Brown's party held out until Tuesday morning, when a company of Marines, led by Col. Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

, quickly broke down the doors to the engine house and took the surviving raiders captive. The seven survivors, including John Brown himself, were quickly tried for treason, murder, and inciting a slave revolt, and were convicted and executed by hanging, in the Jefferson County seat

A seat is a place to sit. The term may encompass additional features, such as back, armrest, head restraint but may also refer to concentrations of power in a wider sense (i.e " seat (legal entity)"). See disambiguation.

Types of seat

The ...

of Charles Town. John Brown was the first person executed for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

in the history of the United States.

However, the raid and the following trials were extensively covered by the press. "The country had not been so excited about anything in twenty years."Corrections by Owen in the July issue, p. 101/ref> Historians frequently credit the raid not for starting the

Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, but for providing the spark that lit the waiting bomb, or as Brown would have put it, causing "the volcano beneath the snow" to erupt. Brown thought that without violence, slavery in the United States would never end. As Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

put it in a famous speech, given in Harpers Ferry, at Storer College

Storer College was a historically Black college in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, that operated from 1867 to 1955. A national icon for Black Americans, in the town where the 'end of American slavery began', as Frederick Douglass famously put i ...

, in 1881, "If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery, he...began the war that ended American slavery and made this a free Republic."

The people of Virginia were furious, outraged at this attempt to get their allegedly happy enslaved to revolt. They took out their anger at any opportunity. Watson Brown was shot when he left the engine house carrying a white flag. William Thompson was shot on the bridge and taken to the hotel parlor; armed men came in, dragged him out, and threw him over the bridge into the river, firing as he fell. The owner of the hotel did not want the carpet ruined by shooting him there.

Burials

The bodies of the slain lay in the streets, on the river banks, or wherever they fell. The body of the first man killed, Dangerfield Newby, lay in the street from 11 am Monday, when he was killed, until Tuesday afternoon, and was partially eaten by hogs; his ears and other body parts were cut off as souvenirs. The bodies of two of the men killed were taken by medical students to Winchester Medical College, for dissection. The remainder, which no local cemetery would accept, were dragged into a "gruesome pile", boxed, and dumped in an unmarked pit on the far side of the Shenandoah. Ten were ultimately buried in 1899 in a single coffin on the John Brown Farm in North Elba, New York, according to a plaque there. They include 8 of the 10 killed during the raid itself. Unwelcome in local cemeteries, they were thrown into two "store boxes", and two Black men, for $5.00 each, buried them, without ceremony, clergy, or marker, on the far side of the Shenandoah (in Clarke County). The family knew that Oliver was buried "by the Shenandoah", but no more. Forty years later, one of the men who buried them was still alive, the unmarked pit was located, and the remains, which could not be matched to specific individuals, were exhumed and taken to North Elba—in secret because locals would have prevented it if they had known—and reburied in a single coffin, which was donated by the town of North Elba. Rev.Joshua Young

Joshua Young (September 23, 1823 – February 7, 1904) was an abolitionist Congregational Unitarian minister who crossed paths with many famous people of the mid-19th century. He received national publicity and lost his pulpit for presiding in 1 ...

, who had presided over Brown's funeral 40 years earlier, performed the last rites. Richard J. Hinton spoke at length. The plaque says the remains of Jeremiah Anderson are there as well, but this is not correct; they are lost, as are those of the two African Americans dissected.

With those 8, in the same coffin and ceremony, were the remains of Hazlitt and Stevens, who had been executed, and whose bodies had been buried at the Eagleswood Military Academy

The Eagleswood Military Academy was a private military academy in Perth Amboy, in Middlesex County, New Jersey, United States, which served antebellum educational needs.

The Eagleswood Military Academy was started by Rebecca Spring (1812–1911) ...

in Perth Amboy, New Jersey

Perth Amboy is a city (New Jersey), city in northeastern Middlesex County, New Jersey, Middlesex County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey, within the New York metropolitan area, New York Metro Area. As of the 2020 United States census, the city' ...

. A relative of Stevens had them disinterred so they could be buried with the others.

None of those killed (10) or executed (7) are buried in Harpers Ferry, Charles Town, or anywhere else in Jefferson County. Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise

Henry Alexander Wise (December 3, 1806 – September 12, 1876) was an American attorney, diplomat, politician and slave owner from Virginia. As the 33rd Governor of Virginia, Wise served as a significant figure on the path to the American Civil ...

said he did not want those executed to be buried anywhere in Virginia, and none were.

Three bodies—1 white (Jerry Anderson) and 2 black (Copeland, Green)—were used for the dissection component of medical studies. The remains after the dissection were apparently discarded. In 1928, a pit containing bones of those dissected was found underneath the foundation of a building being torn down. The medical students and faculty did not know, or care, who they were. Their fourth body, that of Watson Brown, was identified from papers in a pocket as one of Brown's sons, though they did not know which one. It was preserved by a medical school professor and made into an anatomical exhibit, labeled expressing the Virginians' attitude toward abolitionists, and toward John Brown in particular.

Except for those mentioned below as buried by relatives, and the 3 missing bodies that were dissected, the other raiders killed or executed in 1859–1860 are buried at the John Brown Farm State Historic Site

The John Brown Farm State Historic Site includes the home and final resting place of abolitionist John Brown (1800–1859). It is located on John Brown Road in the town of North Elba, 3 miles (5 km) southeast of Lake Placid, New York, whe ...

, near Lake Placid, New York

Lake Placid is a Administrative divisions of New York#Village, village in the Adirondack Mountains in Essex County, New York, Essex County, New York (state), New York, United States. In 2020, its population was 2,205.

The village of Lake Placid ...

.

Note that while there were 10 men killed during the raid itself, and 10 bodies reburied together at the John Brown Farm, the 10 are not the same. 2 of the first 10 (Watson Brown, Jeremiah Anderson) were taken to the Winchester Medical College for use by medical students. To the 8 remaining were added the bodies of Hazlett and Stevens, part of the raid but tried and originally buried separately. A relative of Stevens had his and Hazlett's bodies disinterred from their graves in New Jersey, so they could be buried with the others.

Captured, tried, convicted, and executed by hanging

In the Charles Town jail, by one report, Brown and Hazlett shared a room and a bed, Green and Coppock another, manacled together, and Copeland was in a third room. The rooms in the jail were described as "very large and nicely kept".

Brown was executed on Friday, December 2, four others on December 16, 1859, the negroes (Copeland, Green) in the morning and the whites (Cook, Coppock) in the afternoon, and two (Hazlitt, Stevens) on March 16, 1860. Cook and Coppock attempted to escape, but did not get over the jail wall.

To prevent a rescue, spectators at Brown's execution were very limited. (See .) In contrast, Governor Wise wanted there to be a "tremendous" crowd for the December 16 hangings, and the Sheriff so informed the newspapers. "The execution was witnessed by an immense throng." There was a dress parade; among the participants was Lt. Israel Green of the U.S. Marines, the one who led the assault on

In the Charles Town jail, by one report, Brown and Hazlett shared a room and a bed, Green and Coppock another, manacled together, and Copeland was in a third room. The rooms in the jail were described as "very large and nicely kept".

Brown was executed on Friday, December 2, four others on December 16, 1859, the negroes (Copeland, Green) in the morning and the whites (Cook, Coppock) in the afternoon, and two (Hazlitt, Stevens) on March 16, 1860. Cook and Coppock attempted to escape, but did not get over the jail wall.

To prevent a rescue, spectators at Brown's execution were very limited. (See .) In contrast, Governor Wise wanted there to be a "tremendous" crowd for the December 16 hangings, and the Sheriff so informed the newspapers. "The execution was witnessed by an immense throng." There was a dress parade; among the participants was Lt. Israel Green of the U.S. Marines, the one who led the assault on the engine house

The Severn Valley Railway is a standard-gauge heritage railway in Shropshire and Worcestershire, England. The single-track line runs from Bridgnorth to Kidderminster, calling at four intermediate stations and three request stops ("halts"), fol ...

.

* Buried by relatives

**John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

, 59. His widow took his body to North Elba, and buried him there. On the transportation of his corpse, which was not uneventful, see John Brown's body

"John Brown's Body" ( Roud 771), originally known as "John Brown's Song", is a United States marching song about the abolitionist John Brown. The song was popular in the Union during the American Civil War. The song arose out of the folk hymn ...

.

** Edwin Coppock 24, shot and killed the mayor of Harpers Ferry, Fontaine Beckham, during the raid. He had been with John Brown in Kansas. He was visited in jail by "three Quaker gentlemen from Ohio, with whom he had lived in his boyhood, and an uncle, from the same State." One newspaper report says that his body was sent to his mother in Springdale, Iowa, another that it was sent to a Thomas Winn in Springdale, accompanied by his uncle, "a highly esteemed old Quaker gentleman, who did not sympathize in the least with the misguided and errant young man, and by him he body wasconveyed to the home of his afflicted mother." A different report says that the Quaker was not a relative, but someone who took him in when he became an orphan.

** John Edwin Cook, sometimes spelled Cooke, 29, born in Haddam, Connecticut

Haddam is a town in Middlesex County, Connecticut, United States. The town is part of the Lower Connecticut River Valley Planning Region. The population was 8,452 at the time of the 2020 census. It is the only town in Connecticut that the Conne ...

, but was from Pennsylvania. He had been a teacher. He was Brown's second in command, by one report, had been with Brown in Kansas, and had lived undercover for over a year in Harpers Ferry. He was described as "a man of some intelligence", "a quick-witted, intelligent man", from a good family, who had studied law and taught school. He escaped into Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

after the raid, but Governor Wise offered a reward of $1,000, and he was soon captured. His attorney at the time, Alexander McClure

Alexander Kelly McClure (January 9, 1828 – June 6, 1909) was an American politician, newspaper editor, and writer from Pennsylvania. He served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican member of the Pennsylvania House of Representative ...

, published lengthy recollections. A band played as he was taken from the jail in Chambersburg to the train that would take him to Charles Town for trial.

::On October 28 he was visited in jail by his brother-in-law, Governor Ashbel P. Willard of Indiana, who wanted to be sure that this was his wife's brother, as the family had lost contact with him and had assumed he was dead. Accompanying him, at his request, were Indiana Attorney General Joseph E. McDonald and the U.S. District Attorney for Indiana, Daniel W. Voorhees

Daniel Wolsey Voorhees (September 26, 1827April 10, 1897) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States Senator from Indiana from 1877 to 1897. He was the leader of the Democratic Party and an anti-war Copperhead during ...

. He was escorted to Cook's cell by Senator Mason, who offered to withdraw to give them privacy, but Willard replied that this was not necessary. He advised Cook that he should confess, "so as to exonerate those who were innocent, and to punish those who were implicated, as the only atonement he could now make." He told Cook that he had nothing to hope for but death. A different report, 40 years later, says that Voorhees had arranged with Governor Wise for Cook to escape, but that Cook refused. On November 8 Voorhees addressed the court, calling for mercy for "misled" Cook; his address was published widely. Cook was the only one captured who gave testimony about the other raiders; his testimony at his trial was immediately published as a pamphlet, so as to raise money for one of the victims. This motivated the '' Richmond Enquirer'' to call him "the most guilty of the Charlestown prisoners. So far from being the dupe of Old Brown, Osawatomie is the victim of John E. Cook."

::On December 14 he was visited for some hours by Governor Willard, Voorhees, Willard's wife, and another sister. Body sent to A. P. Willard, care of Cook's brother-in-law Robert Crowley, Williamsburg, New York

Williamsburg is a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Brooklyn, bordered by Greenpoint to the north; Bedford–Stuyvesant to the south; Bushwick and East Williamsburg to the east; and the East River to the west. It was an independen ...

. First buried in Cypress Hill Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

, he was later reburied in Green-Wood Cemetery

Green-Wood Cemetery is a cemetery in the western portion of Brooklyn, New York City. The cemetery is located between South Slope, Brooklyn, South Slope/Greenwood Heights, Brooklyn, Greenwood Heights, Park Slope, Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn, Win ...

, also in Brooklyn.

*Bodies immediately dug up by students of the Winchester Medical College. "They were allowed to remain in the ground but a few moments, when they were taken up and conveyed to Winchester for dissection." (See Burning of Winchester Medical College

The Winchester Medical College (WMC) building, currently located at 302 W. Boscawen Street, Winchester, Virginia, along with all its records, equipment, museum, and library, was burned on May 16, 1862, by Union troops occupying the city. This was ...

.) A letter from Black residents of Philadelphia to Governor Wise, requesting their bodies so as to bury them, had no effect. In the early 20th century a pit containing loose bones of those dissected at the College was discovered.

** ‡ ¶ John Anthony Copeland, Jr., a 24-year-old free Black, described as a mulatto, joined the raiders along with his uncle Lewis Leary. Of Brown's raiders, only Copeland was at all well known. As a leader of the Oberlin-Wellington fugitive slave rescue, he was notorious in Ohio, and was a fugitive from an indictment for his role in that rescue. His parents attempted unsuccessfully to recover his body. On December 29, 3,000 attended a bodyless funeral in Oberlin, Ohio

Oberlin () is a city in Lorain County, Ohio, United States. It is located about southwest of Cleveland within the Cleveland metropolitan area. The population was 8,555 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Oberlin is the home of Oberlin ...

. The last resting place is unknown. Cenotaph memorial in Oberlin.

** ‡ ¶ Shields Green

Shields Green (1836? – December 16, 1859), who also referred to himself as "Emperor", was, according to Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave from Charleston, South Carolina, and a leader in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, in October 1859. He ...

, 22, was an escaped Black slave from South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

. He was captured in the engine house on October 18, 1859, and hanged December 16, 1859, in Charles Town. The body was claimed by Winchester Medical College as a teaching cadaver. The last resting place is unknown. Cenotaph memorial in Oberlin, Ohio.

* Two raiders were not captured until it was too late to hold their trials during the term of the Jefferson County Circuit Court that ended on November 11, after pronouncing sentence on Coppock, Cook, Copeland, and Green on the 10th. The Legislature of Virginia authorized a special term of the Jefferson County Court to deal with them and other pending business. The Court reconvened on February 1; in the meantime Hazlett and Stevens were held in the Jefferson County Jail. Found guilty of the same charges, they were executed on March 16, 1860.

** † Albert E. Hazlett escaped into Pennsylvania but was soon captured. Executed March 16, 1860.

** † Aaron Dwight Stevens

Aaron Dwight Stevens (sometimes misspelled Stephens) (March 15, 1831 – March 16, 1860) was an American abolitionist. The only one of John Brown's raiders with military experience, he was the chief military aide to Brown during his failed ...

(Lee has Aaron C. Stevens), from Connecticut, 29, was the only one of Brown's men who had formal military training. He was shot and captured October 18. Executed March 16, 1860.

:Their bodies were sent immediately to Perth Amboy, New Jersey

Perth Amboy is a city (New Jersey), city in northeastern Middlesex County, New Jersey, Middlesex County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey, within the New York metropolitan area, New York Metro Area. As of the 2020 United States census, the city' ...

, to the house of Marcus and Rebecca B. Spring, the latter of whom had nursed them in the Charles Town jail. A funeral was held there. The bodies were buried at the Eagleswood Cemetery, at the nearby Eagleswood Military Academy

The Eagleswood Military Academy was a private military academy in Perth Amboy, in Middlesex County, New Jersey, United States, which served antebellum educational needs.

The Eagleswood Military Academy was started by Rebecca Spring (1812–1911) ...

, an abolitionist school directed at one time by Theodore Weld

Theodore Dwight Weld (November 23, 1803 – February 3, 1895) was one of the architects of the American abolitionist movement during its formative years from 1830 to 1844, playing a role as writer, editor, speaker, and organizer. He is best kno ...

, next to the graves of James G. Birney and her father Arnold Buffum. In 1898 they were reinterred with eight others at the John Brown Farm in North Elba, New York

North Elba is a Administrative divisions of New York#Town, town in Essex County, New York, Essex County, New York (state), New York, United States. The population was 7,480 at the 2020 census.US Census 2020 Results, QuickFacts, North Elba town, ...

.

Escaped north and never captured

Francis Jackson Merriam andBarclay Coppock

Barclay Coppock (January 4, 1839 – September 4, 1861), also spelled "Coppac", "Coppic", and "Coppoc", was a follower of John Brown (abolitionist), John Brown and a Union Army soldier in the American Civil War. Along with his brother Edwin ...

joined Owen Brown in his prolonged, hazardous escape across Pennsylvania, finally taking refuge in Ashtabula County, Ohio

Ashtabula County ( ) is the northeasternmost county in the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 97,574. The county seat is Jefferson, while its largest city is Ashtabula. The county was created in 1808 and later organ ...

, where John Brown Jr. lived. They were described as voters there.

In November 1859, Governor Wise offered a reward of $500 (~$ in ) each for the apprehension of the four white escapees.

A Charles Town grand jury in February 1860 indicted them, along with Jeremiah Anderson , for "conspiring with slaves to create insurrection". When new Virginia Governor John Letcher

John Letcher (March 29, 1813January 26, 1884) was an American lawyer, journalist, and politician. He served as a Representative in the United States Congress, was the 34th Governor of Virginia during the American Civil War, and later served in ...

asked Governor William Dennison Jr. of Ohio to extradite

In an extradition, one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, into the custody of the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdict ...

them, he declined to issue warrants for their arrest, saying he had not received sufficient justification for doing so.

* Charles Plummer Tidd, a "lumberman" from Maine, had been a farmer in Kansas, where he met Brown. He died during the Civil War, 1862. Another reference says he was from Worcester County, Massachusetts

Worcester County ( ) is a County (United States), county in the U.S. state of Massachusetts. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 862,111, making it the second-most populous county in Massachusetts. Being 1,510.6 ...

. After enlisting in the Union Army, while his regiment was stationed at Roanoke Island

Roanoke Island () is an island in Dare County, bordered by the Outer Banks of North Carolina. It was named after the historical Roanoke, a Carolina Algonquian people who inhabited the area in the 16th century at the time of English colonizat ...

, North Carolina, he died of a fever; his remains are buried at New Bern, North Carolina

New Bern, formerly Newbern, is a city in Craven County, North Carolina, United States, and its county seat. It had a population of 31,291 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is located at the confluence of the Neuse River, Neuse a ...

. Owen Brown, upset at the reaction to his comments on Tidd in his interview published in ''The Atlantic

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher based in Washington, D.C. It features articles on politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 185 ...

'', said in a reply letter: " impressions of Tidd are that he was a very warm friend, generally of peaceful disposition, true, and devoted to his ideas of rights and moral principle. He was firm and persistent in what he undertook, somewhat inclined to be arbitrary, and with a temper not always under perfect control. As a whole, he stands far above the average of men. I hold for him a warm friendship."

The following three remained at the Kennedy Farm in Maryland, guarding the weapons.

* Owen Brown, after a very difficult trip, made it to the safety of his brother Jason's house in Ohio. For many years he raised grapes on an island in Lake Erie, "for the Chicago market" (not for wine). He died January 8, 1889, in Pasadena, California

Pasadena ( ) is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States, northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is the most populous city and the primary cultural center of the San Gabriel Valley. Old Pasadena is the city's original commerci ...

. His funeral was an event (with marching band) and his burial site, atop a peak named (because of him) "Brown's Peak", is a local tourist attraction.

* Barclay Coppock

Barclay Coppock (January 4, 1839 – September 4, 1861), also spelled "Coppac", "Coppic", and "Coppoc", was a follower of John Brown (abolitionist), John Brown and a Union Army soldier in the American Civil War. Along with his brother Edwin ...

, 22 or 23, from Iowa like his brother, safely reached Canada. He died in the Union Army in 1861.

* Francis Jackson Meriam

Francis Jackson Meriam (sometimes misspelled Merriam) was an American abolitionist, born on November 17, 1837, in Framingham, Massachusetts, Framingham, Massachusetts, and died on November 28, 1865, in New York City. He was named for his grandfath ...

, 28 or 30, "of the wealthy Massachusetts Meriams", who "had furnished a good deal of money to the cause". Two days before the attack on Harpers Ferry, before a lawyer in Chambersburg

Chambersburg is a borough in and the county seat of Franklin County, in the South Central region of Pennsylvania, United States. It is in the Cumberland Valley, which is part of the Great Appalachian Valley, and north of Maryland and the Ma ...

, accompanied by Kagi, he made his will, leaving most of his estate to the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society

The New England Anti-Slavery Society (1831–1837) was formed by William Lloyd Garrison, editor of '' The Liberator,'' in 1831. ''The Liberator'' was its official publication.

Based in Boston, Massachusetts, members of the New England Anti-slave ...

. After the raid, "he reached the railroad in Maryland, passed on to Philadelphia, where he remained overnight at the Merchants' Hotel, registering his true name, and proceeded next morning to Boston." Another source says that he went to Canada before coming to "his physician in Boston. He served in the Union army as a captain in the 3rd South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Colored)

The 3rd South Carolina Colored Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment of African-American in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Service

The 3rd South Carolina Infantry was organized at Hilton Head, South Carolina and mustered int ...

. (Colored regiments had white officers.) He died of natural causes in 1865. A conflicting report says that he "went to Mexico to join enitoJuárez in 1865...and has not since been heard from".

(The plaque at the John Brown Farm says a negro named John Anderson escaped; the source for this is apparently biographer Franklin Sanborn, who has nothing else to say about him and omits him from the book index. There was no person of that name among Brown's raiders; Brown received in jail a letter from John Q. Anderson, brother of Jeremiah, inquiring about his brother. Later Sanborn calls John Anderson "rather mythical", someone "whom Hayden enlisted for Brown, but who never got to the Ferry".)

Black people who joined Brown's rebellion

Brown said many times that he had expected a large number of enslaved black people of Jefferson County to flee their owners and assist him in the raid and afterwards. This did not happen, a main reason for the raid's failure. However, this was extended, especially by Virginia Governor Wise, to a claim that black people were hostile to Brown and gave him no support at all. Both black and white people denied black participation. Any black person who could claim they were there involuntarily did so, and most did, as otherwise they would have been executed. (Shields Green was not successful at this, since his skin was so dark that Harpers Ferry residents immediately recognized he was not a local.) The whites went along with this. It was a basic belief in the South at the time that their slaves were happy, and they would be happier if abolitionists just left them alone; they were highly motivated to believe that no slaves supported Brown. Another raider who escaped, C. P. Tidd, said much the same. Captain Dangerfield reported seeing "negroes armed with pikes" when he arrived at the Armory. According to a local newspaper, "the slaves for miles around Harper's Ferry, though well kept and kindly treated, were well informed as to John Brown's movement, and prepared to take part in the insurrection." Brown's mistake was that, afraid of betrayal by Cook or Forbes, he "suddenly changed the time to two weeks earlier". He failed to notify the slaves of the change. A correspondent from the ''Cincinnati Commercial

The ''Cincinnati Commercial Tribune'' was a major daily newspaper in Cincinnati, Ohio, formed in 1896, and folded in 1930.(3 December 1930)OLDEST NEWSPAPER IN CINCINNATI QUITS; Commercial Tribune Stopped by McLean Interests After Political Shift ...

'', in Charles Town for the execution, reported: "As to the negroes round about Harper's Ferry and Charlestown there can be no doubt but they were deeply interested in the events that have recently taken place, and that many of them looked upon the outbreak, as the lifting of the dark cloud of slavery from their race. ...It is believed that many of the negroes did know something extraordinary was about to happen in the vicinity of Harper's Ferry, and a well informed and candid gentleman told me that he had no doubt Brown believed his plans were found out, or about to be found out, and struck the blow two weeks at least, and perhaps six weeks earlier than he intended. This gentleman is convinced that if the plans had been perfected, Brown would actually have had a negro for every one of his spears, and would have made his way through the mountains of Maryland into Pennsvlvania."

So Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

's statement, in his "Report", that local black people gave Brown ''no'' voluntary assistance at all, is not correct, though it appeared again in the Senate Special Committee report and in many Southern reports on the raid. Andrew Hunter, Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise

Henry Alexander Wise (December 3, 1806 – September 12, 1876) was an American attorney, diplomat, politician and slave owner from Virginia. As the 33rd Governor of Virginia, Wise served as a significant figure on the path to the American Civil ...

's attorney and the prosecutor in Charles Town, informed Wise confidentially that: "We believed and knew, as we thought then and still think, that he rowncould not seduce our slaves. It may be here remarked that, so far as I knew or learned from any quarter, not a single one of the slaves in the county of Jefferson or in Maryland, adjacent, ever did join him in his raid, except by coercion, and then they escaped as soon as they could and went back to their homes." Judge Parker concurred. Wise turned this statement into a claim he made repeatedly in speeches: "not a slave around was found faithless". These "faithful slaves" who allegedly refused to help Brown at Harpers Ferry became a key element in the "Lost Cause

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy, known simply as the Lost Cause, is an American pseudohistorical and historical negationist myth that argues the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil War was just, heroic, and not cente ...

" myth of happy Antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern US

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum architectu ...

Southern life. The United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) is an American neo-Confederate hereditary association for female descendants of Confederate Civil War soldiers engaging in the commemoration of these ancestors, the funding of monuments to them, a ...

had later a "Faithful Slave Committee" trying to honor them with a monument in Harpers Ferry (see Hayward Shepherd Monument).

However, we know positively, said a newspaper story, that some 25 enslaved black people, out of 200 acquainted to some degree with Brown's project, helped the raiders; they all claimed to have been impressed (forced). Another source says that "there has not been more than 20 negroes under arms." The True Bill of Indictment gives the names of 11 slaves whom the conspirators had allegedly incited to revolt, 4 of Lewis Washington (Jim, Sam, Mason, and Catesby), and 7 of John Allstadt (Henry, Levi, Ben, Herry, Phil, George, and Bill), plus "other slaves to the jurors unknown". Of those, we have clear documentation of two that were with Brown voluntarily. One was Jim, "a young coachman hired by Lewis Washington from an owner in Winchester"; he drowned attempting to flee by crossing the river. "There is no doubt that Washington's negro coachman, Jim, who was chased into the river and drowned, had joined the rebels with a good will. A pistol was found on him, and he had his pockets filled with ball cartridges, when he was fished out of the river."

Ben, who was owned by John Allstadt, was captured and almost lynched. He died in the Charles Town jail of "pneumonia and fright", along with his mother Ary, also owned by Allstadt, who had come to nurse him. Both owners filed claims with the government of Virginia for compensation for the loss of their "property" in the raid; it is not known if their claims were successful.

These are not the only black people that fled their owners and participated in the raid. According to Frederick Douglass, "fifty slaves were collected and emancipation was proclaimed in Virginia and Maryland".

The first report on "insurrectionists" killed gave the number of 17, but only 10 were Brown's men, and the other 7 must have been liberated slaves helping him. One was "an old slaveman of the neighborhood, who distinguished himself by reckless courage." He shot armorer Boerly after the latter shot Newby. "He was probably killed soon after." "In the engine house there were "a few negroes that had been liberated and armed by Brown". Except for Ben and Jim, their names are unknown. "The number of colored men slain by the reckless fire of the belligerants is given as seventeen." There were twelve or thirteen bodies immediately buried, but only the names of eight are known. There were other slaves killed whose bodies were carried away by the river. According to Louis DeCaro, at the peak there were 20 to 30 local slaves involved, who quickly and quietly went back to their masters' when it became clear the raid was failing.

According to the 1860 census, there were 589 escaped slaves in Jefferson County. "No adjacent Counties reported any rvery, very few such escapes in the same census." There is a long list of fires set in Jefferson County during the final months of 1859, including those at the farms of men who had been on the jury that convicted Brown.

In Harpers Ferry, a Black Voices Museum, at 17 High Street, was operating in 2020.

Gallery

Joshua Young

Joshua Young (September 23, 1823 – February 7, 1904) was an abolitionist Congregational Unitarian minister who crossed paths with many famous people of the mid-19th century. He received national publicity and lost his pulpit for presiding in 1 ...

says the benediction over reburial of John Brown's collaborators.

Notes

References

Further reading

Biographies of the raiders

* John E. Cook. * John Anthony Copeland. * Shields Green. * African American soldiers in John Brown's Army.Other books

* A brief, anonymous, and inaccurate article of 1869. * * Owen Brown comments on raiders Charles Plummer Tidd, John E. Cook, Barclay Coppoc, and Francis Jackson Merriam. * * * Reprinted in the '' Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly'', 1949. * Richard J. Hinton, who became a newspaper reporter and editor, and later a geologist, was an "intimate friend" of John Brown in Kansas. * * * *Sources

* {{John Brown's Raid on Harpers Ferry Winchester Medical College Robert E. Lee