Johann Wilhelm Ritter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Johann Wilhelm Ritter (16 December 1776 – 23 January 1810). was a German chemist, physicist and

In 1800, shortly after the invention of the voltaic pile, William Nicholson and Anthony Carlisle discovered that water could be decomposed by electricity. Shortly afterward, Ritter also discovered the same effect, independently. Besides that, he collected and measured the amounts of hydrogen and oxygen produced in the reaction. He also discovered the process of

In 1800, shortly after the invention of the voltaic pile, William Nicholson and Anthony Carlisle discovered that water could be decomposed by electricity. Shortly afterward, Ritter also discovered the same effect, independently. Besides that, he collected and measured the amounts of hydrogen and oxygen produced in the reaction. He also discovered the process of

Johann W. Ritter

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ritter, Johann Wilhelm 1776 births 1810 deaths People from Chojnów Natural philosophers 19th-century German physicists

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

. He was born in Samitz (Zamienice) near Haynau (Chojnów) in Silesia (then part of Prussia, since 1945 in Poland), and died in Munich.

Life and work

Johann Wilhelm Ritter's first involvement with science began when he was 14 years old. He became an apprentice to an apothecary in Liegnitz (Legnica), and acquired a deep interest in chemistry. He began medicine studies at the University of Jena in 1796. A self-taught scientist, he made many experimental researches on chemistry, electricity and other fields. Ritter belonged to the German Romantic movement. He was personally acquainted with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Alexander von Humboldt,Johann Gottfried Herder

Johann Gottfried von Herder ( , ; 25 August 174418 December 1803) was a German philosopher, theologian, poet, and literary critic. He is associated with the Enlightenment, ''Sturm und Drang'', and Weimar Classicism.

Biography

Born in Mohrun ...

and Clemens Brentano. He was strongly influenced by Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, who was the main philosopher of the ''Naturphilosophie

''Naturphilosophie'' (German for "nature-philosophy") is a term used in English-language philosophy to identify a current in the philosophical tradition of German idealism, as applied to the study of nature in the earlier 19th century. German sp ...

'' movement. In 1801, Hans Christian Ørsted

Hans Christian Ørsted ( , ; often rendered Oersted in English; 14 August 17779 March 1851) was a Danish physicist and chemist who discovered that electric currents create magnetic fields, which was the first connection found between electricity ...

visited Jena and became his friend. Several of Ritter's researches were later reported by Ørsted, who was also strongly influenced by the philosophical outlook of ''Naturphilosophie''.Roberto de Andrade Martins (2007), "Ørsted, Ritter and magnetochemistry", in ''Hans Christian Ørsted and the Romantic Legacy in Science: Ideas, Disciplines, Practices'', eds. R.M. Brain, R. S. Cohen & O. Knudsen (Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, vol. 241), New York: Springer, pp. 339-385. ().

Ritter's first scientific researches concerned some galvanic phenomena. He interpreted the physiological effects observed by Luigi Galvani

Luigi Galvani (, also ; ; la, Aloysius Galvanus; 9 September 1737 – 4 December 1798) was an Italian physician, physicist, biologist and philosopher, who studied animal electricity. In 1780, he discovered that the muscles of dead frogs' legs ...

and other researchers as due to the electricity generated by chemical reactions. His interpretation is closer to the one accepted nowadays than those proposed by Galvani (“animal electricity”) and Alessandro Volta

Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio Anastasio Volta (, ; 18 February 1745 – 5 March 1827) was an Italian physicist, chemist and lay Catholic who was a pioneer of electricity and power who is credited as the inventor of the electric battery and the ...

(electricity generated by metallic contact), but it was not accepted at the time.

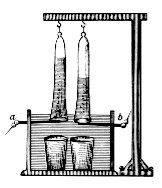

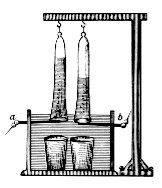

In 1800, shortly after the invention of the voltaic pile, William Nicholson and Anthony Carlisle discovered that water could be decomposed by electricity. Shortly afterward, Ritter also discovered the same effect, independently. Besides that, he collected and measured the amounts of hydrogen and oxygen produced in the reaction. He also discovered the process of

In 1800, shortly after the invention of the voltaic pile, William Nicholson and Anthony Carlisle discovered that water could be decomposed by electricity. Shortly afterward, Ritter also discovered the same effect, independently. Besides that, he collected and measured the amounts of hydrogen and oxygen produced in the reaction. He also discovered the process of electroplating

Electroplating, also known as electrochemical deposition or electrodeposition, is a process for producing a metal coating on a solid substrate through the reduction of cations of that metal by means of a direct electric current. The part to be ...

. In 1802 he built his first electrochemical cell, with 50 copper discs separated by cardboard disks moistened by a salt solution.

Ritter made several self-experiments applying the poles of a voltaic pile to his own hands, eyes, ears, nose and tongue. He also described the difference between the physiological effects of the two poles of the pile, although some of the effects he reported were not confirmed afterwards.

Many of Ritter's researches were guided by a search for polarities in the several "forces" of nature, and for the relation between those "forces" – two of the assumptions of ''Naturphilosophie''. In 1801, after hearing about the discovery of "heat rays" ( infrared radiation) by William Herschel (in 1800), Ritter looked for an opposite (cooling) radiation at the other end of the visible spectrum. He did not find exactly what he expected to find, but after a series of attempts he noticed that silver chloride was transformed faster from white to black when it was placed at the dark region of the Sun's spectrum, close to its violet end. The "chemical rays" found by him were afterwards called ultraviolet radiation.

Some of Ritter's researches were acknowledged as important scientific contributions, but he also claimed the discovery of many phenomena that were not confirmed by other researchers. For instance: he reported that the Earth had electric poles that could be detected by the motion of a bimetallic needle; and he claimed that he could produce the electrolysis of water using a series of magnets, instead of Volta's piles.

Ritter had no regular income and never became a university professor, although in 1804 he was elected a member of the Bavarian Academy of Science (in Munich). He married in 1804 and had four children, but he was unable to provide the needs of his family. Plagued by financial difficulties and suffering from weak health (perhaps aggravated by his electrical self-experimentation), he died young in 1810, as a poor man.

See also

* Timeline of hydrogen technologies *Timeline of particle discoveries

This is a timeline of subatomic particle discoveries, including all particles thus far discovered which appear to be elementary (that is, indivisible) given the best available evidence. It also includes the discovery of composite particles and an ...

References

Sources

* Siegfried Zielinski: Electrification, tele-writing, seeing close-up: Johann Wilhelm Ritter, Joseph Chudy, and Jan Evangelista Purkyne, in: ''Deep Time of the Media. Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means'' (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), .External links

Johann W. Ritter

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ritter, Johann Wilhelm 1776 births 1810 deaths People from Chojnów Natural philosophers 19th-century German physicists