Johann Fischart on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Johann Baptist Fischart (c. 1545 – 1591) was a German satirist and

Fischart wrote under pseudonyms; such as Mentzer, Menzer, Reznem, Huidrich Elloposkleros, Jesuwalt Pickhart, Winhold Alkofribas Wustblutus, Ulrich Mansehr von Treubach, and Im Fischen Gilts Mischen. There is doubt whether some of the works attributed to him are really his. More than 50

Fischart wrote under pseudonyms; such as Mentzer, Menzer, Reznem, Huidrich Elloposkleros, Jesuwalt Pickhart, Winhold Alkofribas Wustblutus, Ulrich Mansehr von Treubach, and Im Fischen Gilts Mischen. There is doubt whether some of the works attributed to him are really his. More than 50

publicist

A publicist is a person whose job is to generate and manage publicity for a company, a brand, or public figure – especially a celebrity – or for a work such as a book, film, or album. Publicists are public relations specialists w ...

.

Biography

Fischart was born, probably, at Strasbourg (but according to some accounts atMainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

), in or about the year 1545, and was educated at Worms Worms may refer to:

*Worm, an invertebrate animal with a tube-like body and no limbs

Places

*Worms, Germany, a city

** Worms (electoral district)

* Worms, Nebraska, U.S.

*Worms im Veltlintal, the German name for Bormio, Italy

Arts and entertai ...

in the house of Kaspar Scheid, whom in the preface to his ''Eulenspiegel'' he mentions as his cousin and preceptor. He appears to have travelled in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

and England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, and on his return to have taken the degree of ''doctor juris'' at Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS) ...

.

Most of his works were written from 1575 to 1581. During this period, he lived with, and was probably associated in the business of, his sister's husband, Bernhard Jobin, a printer at Strasbourg who published many of his books. In 1581 Fischart was attached as advocate to the Reichskammergericht (imperial court of appeal) at Speyer

Speyer (, older spelling ''Speier'', French: ''Spire,'' historical English: ''Spires''; pfl, Schbaija) is a city in Rhineland-Palatinate in Germany with approximately 50,000 inhabitants. Located on the left bank of the river Rhine, Speyer li ...

. In 1583, he married and was appointed ''Amtmann

__NOTOC__

The ''Amtmann'' or ''Ammann'' (in Switzerland) was an official in German-speaking countries of Europe and in some of the Nordic countries from the time of the Middle Ages whose office was akin to that of a bailiff. He was the most se ...

'' (magistrate) at Forbach

Forbach ( , , ; gsw, Fuerboch) is a commune in the French department of Moselle, northeastern French region of Grand Est.

It is located on the German border approximately 15 minutes from the center of Saarbrücken, Germany, with which it co ...

near Saarbrücken

Saarbrücken (; french: link=no, Sarrebruck ; Rhine Franconian: ''Saarbrigge'' ; lb, Saarbrécken ; lat, Saravipons, lit=The Bridge(s) across the Saar river) is the capital and largest city of the state of Saarland, Germany. Saarbrücken is ...

. He died there in the winter of 1590–1591.

Influence

Thirty years after Fischart's death, his writings, once so popular, were almost entirely forgotten. Recalled to the public attention by Johann Jakob Bodmer andGotthold Ephraim Lessing

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (, ; 22 January 1729 – 15 February 1781) was a philosopher, dramatist, publicist and art critic, and a representative of the Enlightenment era. His plays and theoretical writings substantially influenced the developm ...

, it was only around the end of the 1800s that his works came to be a subject of academic investigation, and his position in German literature

German literature () comprises those literary texts written in the German language. This includes literature written in Germany, Austria, the German parts of Switzerland and Belgium, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, South Tyrol in Italy and to a l ...

to be fully understood.

Fischart studied not only ancient literature, but also the literature of Italy, France, the Netherlands and England. He was a lawyer, a theologian, a satirist and the most powerful Protestant publicist of the counter-reformation period; in politics he was a republican. His satire was levelled mercilessly at all perversities in the public and private life of his time, at astrological superstition, scholastic pedantry, ancestral pride, but especially at the papal

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

dignity and the lives of the priesthood and the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

. He indulged in the wildest witticisms, the most extreme caricature

A caricature is a rendered image showing the features of its subject in a simplified or exaggerated way through sketching, pencil strokes, or other artistic drawings (compare to: cartoon). Caricatures can be either insulting or complimentary, a ...

, obscenity

An obscenity is any utterance or act that strongly offends the prevalent morality of the time. It is derived from the Latin ''obscēnus'', ''obscaenus'', "boding ill; disgusting; indecent", of uncertain etymology. Such loaded language can be u ...

, double entendre; but all this he did with a serious purpose.

As a poet, he is characterized by the eloquence and picturesqueness of his style and the symbolical language he employed. He treats the German language

German ( ) is a West Germanic language mainly spoken in Central Europe. It is the most widely spoken and official or co-official language in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and the Italian province of South Tyrol. It is als ...

with the greatest freedom, coining new words and turns of expression without any regard to analogy, and displaying, in his most arbitrary formations, erudition and wit.

Works

Fischart wrote under pseudonyms; such as Mentzer, Menzer, Reznem, Huidrich Elloposkleros, Jesuwalt Pickhart, Winhold Alkofribas Wustblutus, Ulrich Mansehr von Treubach, and Im Fischen Gilts Mischen. There is doubt whether some of the works attributed to him are really his. More than 50

Fischart wrote under pseudonyms; such as Mentzer, Menzer, Reznem, Huidrich Elloposkleros, Jesuwalt Pickhart, Winhold Alkofribas Wustblutus, Ulrich Mansehr von Treubach, and Im Fischen Gilts Mischen. There is doubt whether some of the works attributed to him are really his. More than 50 satirical

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming o ...

works, in both prose and verse, remain, and are considered to be his authentic work.

Among works believed to be his are:

*''Nachtrab oder Nebelkräh'', a satire against Jakob Rabe, a Catholic convert (1570)

*''Von St. Dominici des Predigermönchs und St Francisci Barfüssers artlichem Leben'', a poem

Poetry (derived from the Greek '' poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings ...

with the expressive motto ''Sie haben Nasen und riechens nit'' ("Ye have noses and smell it not"), written to defend the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

s against certain accusations, one of which was that Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Luther ...

held communion

Communion may refer to:

Religion

* The Eucharist (also called the Holy Communion or Lord's Supper), the Christian rite involving the eating of bread and drinking of wine, reenacting the Last Supper

**Communion (chant), the Gregorian chant that ac ...

with the devil

A devil is the personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conceptions of ...

(1571)

*''Eulenspiegel Reimensweis'' (written 1571, published 1572)

*''Aller Praktik Grossmutter'', after Rabelais' ''Prognostication Pantagrueline'' (1572, Johann Scheible ed. 1847)

*''Flöh Haz, Weiber Traz'', in which he describes a battle between flea

Flea, the common name for the order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult fleas grow to about long, a ...

s and women (1573, Scheible ed. 1848)

*''Affentheuerliche und ungeheuerliche Geschichtschrift vom Leben, Rhaten und Thaten der . . . Helden und Herren Grandgusier Gargantoa und Pantagruel'', also after Rabelais (1575, and again under the modified title, ''Naupengeheurliche Geschichtklitterung'', 1577)

*''Neue künstliche Figuren biblischer Historien'' (1576)

*''Anmahnung zur christlichen Kinderzucht'' (1576)

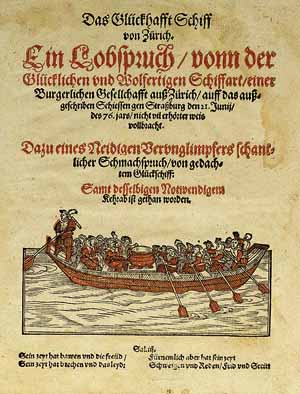

*''Das glückhafft Schiff von Zürich'' (The Lucky Ship of Zürich), a poem commemorating the adventure of a company of Zürich arquebusiers, who sailed from their native town to Strasbourg in one day, and brought, as a proof of this feat, a kettleful of ''Hirsebrei'' (millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most species generally referred to as millets belong to the tribe Paniceae, but some millets ...

gruel), which had been cooked in Zürich, still warm into Strasbourg, and intended to illustrate the proverb "perseverance overcomes all difficulties" (1576, republished 1828, with an introduction by the poet Ludwig Uhland)

*''Podagrammisch Trostbüchlein'' (1577, Scheible ed. 1848)

*''Philosophisch Ehzuchtbüchlein'' (1578, Scheible ed. 1848)

*''Bienenkorb des heiligen römischen Immenschwarms, &c.'', a modification of the Dutch ''De roomsche Byen-Korf'', by Philipp Marnix of St. Aldegonde (1579, reprinted 1847)

*''Der heilig Brotkorb'', after Calvin's ''Traité des reliques'' (1580)

*''Das vierhörnige Jesuiterhütlein'', a rhymed satire against the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

(1580)

He also wrote a number of smaller poems. To Fischart also have been attributed some ''Psalmen und geistliche Lieder'' which appeared in a Strasbourg hymn-book of 1576.

Notes

References

* *External links

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Fischart, Johann 1540s births 1591 deaths Writers from Strasbourg Alsatian-German people Literature of the German Renaissance Writers from Mainz German male writers