Joel Roberts Poinsett on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Joel Roberts Poinsett (March 2, 1779December 12, 1851) was an American physician, diplomat and botanist. He was the first U.S. agent in South America, a member of the South Carolina legislature and the

Poinsett arrived in the Russian capital of

Poinsett arrived in the Russian capital of

He served as a "special agent" to two South American countries from 1810 to 1814, Chile and Argentina. President

He served as a "special agent" to two South American countries from 1810 to 1814, Chile and Argentina. President

Poinsett was aware that his friends had nominated him to represent Charleston, South Carolina, in the state legislature. In Greenville on his way back home, he learned that he had won the nomination and had a seat in the State House of Representatives. As he was beginning his first term in April 1817, the rumored position of American envoy to South America became reality. On April 25, 1817, acting Secretary of State

Poinsett was aware that his friends had nominated him to represent Charleston, South Carolina, in the state legislature. In Greenville on his way back home, he learned that he had won the nomination and had a seat in the State House of Representatives. As he was beginning his first term in April 1817, the rumored position of American envoy to South America became reality. On April 25, 1817, acting Secretary of State

Poinsett simultaneously served as a special envoy to Mexico from 1822 to 1823, when the government of James Monroe became concerned about the stability of newly independent Mexico. Poinsett, a supporter of the

Poinsett simultaneously served as a special envoy to Mexico from 1822 to 1823, when the government of James Monroe became concerned about the stability of newly independent Mexico. Poinsett, a supporter of the

Joel Roberts Poinsett, Political Memory of Mexico ....for a more balanced view of Ponsett's involvement in Mexico(Article in Spanish)

Handbook of Texas Online: POINSETT, JOEL ROBERTS

Joel Roberts Poinsett: The Man Behind The Flower

Joel Roberts Poinsett Historical Marker

*

Poinsett State Park In Wedgefield South Carolina

Poinsett as a Mason in Greenville, SC

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together the ...

, the first United States Minister to Mexico, a Unionist leader in South Carolina during the Nullification Crisis, Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

under Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

, and a co-founder of the National Institute for the Promotion of Science and the Useful Arts (a predecessor of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

).

Early travels

Joel Roberts Poinsett was born in 1779 in Charleston, South Carolina, to a wealthyphysician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

, Elisha Poinsett, and his wife Katherine Ann Roberts. He was educated in Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

and University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

, gaining expertise in languages, the law, and military affairs.

Touring in Europe

In 1800 Poinsett returned to Charleston hoping to pursue a military career. His father did not want his son to be a soldier. Hoping to entice his son to settle into the Charleston aristocracy, Poinsett had his son study law underHenry William DeSaussure

Henry William de Saussure (August 16, 1763 – March 26, 1839) was an American lawyer, state legislator and jurist from South Carolina who became a political leader as a member of the Federalist Party following the Revolutionary War. He was ap ...

, a prominent lawyer of Charleston. Poinsett was not interested in becoming a lawyer, and convinced his parents to allow him to go on an extended tour of Europe in 1801. DeSaussure sent with him a list of law books including Blackstone's ''Commentaries'' and Burn's ''Ecclesiastical Law'', just in case young Poinsett changed his mind regarding the practice of law.

Beginning in 1801, Poinsett traveled the European continent. In the spring of 1802, Poinsett left France for Italy traveling through the Alps and Switzerland. He visited the cities of Naples and hiked up Mount Etna

Mount Etna, or simply Etna ( it, Etna or ; scn, Muncibbeḍḍu or ; la, Aetna; grc, Αἴτνα and ), is an active stratovolcano on the east coast of Sicily, Italy, in the Metropolitan City of Catania, between the cities of Messina a ...

on the island of Sicily. In the spring of 1803 he arrived in Switzerland and stayed at the home of Jacques Necker

Jacques Necker (; 30 September 1732 – 9 April 1804) was a Genevan banker and statesman who served as finance minister for Louis XVI. He was a reformer, but his innovations sometimes caused great discontent. Necker was a constitutional mona ...

and his daughter, Madame de Stael Madame may refer to:

* Madam, civility title or form of address for women, derived from the French

* Madam (prostitution), a term for a woman who is engaged in the business of procuring prostitutes, usually the manager of a brothel

* ''Madame'' ( ...

. Necker, French Finance Minister from 1776 to 1781 under Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was e ...

, had been driven into exile by Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

.

On one occasion, Robert Livingston, the United States minister to France, was invited for a visit while he was touring Savoy, France, and Switzerland. Poinsett was compelled to assume the role of interpreter between the deaf Livingston and the aged Necker, whose lack of teeth made his speech almost incomprehensible. Fortunately, Madame de Stael tactfully assumed the duty of translation for her elderly father.

In October 1803, Poinsett left Switzerland for Vienna, Austria

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, and from there journeyed to Munich. In December he received word that his father was dead, and that his sister, Susan, was seriously ill. He immediately secured passage back to Charleston. Poinsett arrived in Charleston early in 1804, months after his father had been laid to rest. Hoping to save his sister's life, Poinsett took her on a voyage to New York, remembering how his earlier voyage to Lisbon had intensified his recovery. Yet, upon arriving in New York City, Susan Poinsett died. As the sole remaining heir, Poinsett inherited a small fortune in town houses and lots, plantations, bank stock, and "English funds." The entire Poinsett estate was valued at a hundred thousand dollars or more.

Travel in Russia

Poinsett arrived in the Russian capital of

Poinsett arrived in the Russian capital of St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

in November 1806. Levett Harris, consul of the United States at St. Petersburg, and the highest American official in the country, hoped to introduce Poinsett at court to Czar Alexander. Learning that Poinsett was from South Carolina, the Empress asked him if he would inspect the cotton factories under her patronage. Poinsett and Consul Harris traveled by sleigh to Cronstadt

Kronstadt (russian: Кроншта́дт, Kronshtadt ), also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt or Kronštádt (from german: link=no, Krone for "crown" and ''Stadt'' for "city") is a Russian port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city of ...

to see the factories. Poinsett made some suggestions on improvement, which the Dowager Empress

Empress dowager (also dowager empress or empress mother) () is the English language translation of the title given to the mother or widow of a Chinese, Japanese, Korean, or Vietnamese emperor in the Chinese cultural sphere.

The title was al ...

accepted. Poinsett did not believe the cotton industry could be successful in Russia because of the necessity of employing serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

who received no compensation and therefore could have no interest in its prosperity. Furthermore, he believed that the institution of serfdom made it difficult for Russia to have a merchant marine or become industrialized.

In January 1807, Czar Alexander and Poinsett dined at the Palace. Czar Alexander attempted to entice Poinsett into the Russian civil or military service. Poinsett was hesitant, which prompted Alexander to advise him to "see the Empire, acquire the language, study the people", and then decide. Always interested in travel, Poinsett accepted the invitation and left St. Petersburg in March 1807 on a journey through southern Russia. He was accompanied by his English friend Philip Yorke, Viscount Royston and eight others.

With letters recommending them to the special care of all Russian officials, Poinsett and Royston made their way to Moscow. They were among the last westerners to see Moscow before its burning in October 1812 by Napoleon's forces. From Moscow they traveled to the Volga River

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchm ...

, and then by boat to Astrakhan

Astrakhan ( rus, Астрахань, p=ˈastrəxənʲ) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in Southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of ...

, situated at the mouth of the river. Poinsett's company now entered the Caucasus, containing a very diverse population, and only recently acquired by Russia through conquests by Czars Peter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

and Catherine the Great. Because of ethnic conflict, the area was extremely dangerous. They were provided with a Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

escort as they traveled between Tarki and Derbent, but when a Tartar dignitary claimed that this would only provoke danger, the escort was bypassed for the security of the Tartar chiefs. This new security increased the numbers in Poinsett's company, which they believed made it less vulnerable to attack as it passed out of Russia proper. Thus, they were joined by a Persian merchant, who was transporting young girls he had acquired in Circassia

Circassia (; also known as Cherkessia in some sources; ady, Адыгэ Хэку, Адыгей, lit=, translit=Adıgə Xəku, Adıgey; ; ota, چرکسستان, Çerkezistan; ) was a country and a historical region in the along the northeast ...

to Baku and harems in Turkey. With a strong Persian and Kopak guard, the party left Derbent and entered the realm of the Khan of Kuban

Kuban (Russian and Ukrainian: Кубань; ady, Пшызэ) is a historical and geographical region of Southern Russia surrounding the Kuban River, on the Black Sea between the Don Steppe, the Volga Delta and the Caucasus, and separated fr ...

.

While traveling through the Khanate, a tribal chief stole some of the horses in Poinsett's party. Poinsett boldly decided to go out of his way to the court of the Khan in the town of Kuban to demand their return. As there were normally never any foreigners in this place, the Khan was surprised. Of course, he had never heard of the United States, and Poinsett did the best he could to answer all the questions the Khan had. In order to convey the greatness of the U.S., Poinsett spoke at length on its geography. The Khan referred to President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the nati ...

as the Shah of America. Finally, Poinsett stated that the theft of his horses would reflect badly on the fair name of the Khanate. The Khan was impressed and told Poinsett that the head of the guilty chief was his for the asking, yet since the thief had made it possible for him to accept such a distinguished visitor, perhaps a pardon might be in order.

Poinsett's company traveled to Baku on the Caspian Sea. He noted that because of the petroleum pits in the region, it had long been a spot of pilgrimage for fire-worshipers. He became one of the earliest U.S. travelers to the Middle East, where, in 1806, the Persian khan showed him a pool of petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crude ...

, which he speculated might someday be used for fuel.

Attracted by the military movements in the Caucasus Mountains, Poinsett visited Erivan

Yerevan ( , , hy, Երևան , sometimes spelled Erevan) is the capital and largest city of Armenia and one of the world's oldest continuously inhabited cities. Situated along the Hrazdan River, Yerevan is the administrative, cultural, and i ...

, which was then besieged by the Russian Army. After a time with the troops, Poinsett and company journeyed through the mountains of Armenia to the Black Sea. Avoiding Constantinople because of conflict between Russia and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, the party proceeded to the Crimea, then through Ukraine, reaching Moscow late in 1807. The trip had been hazardous and Poinsett's health was much impaired. Furthermore, of the nine who had set out on the journey the previous March, Poinsett and two others were the only survivors.

Upon his return to Moscow, Czar Alexander discussed the details of Poinsett's trip with him and offered him a position as colonel in the Russian Army. However, news had reached Russia of the attack of the Chesapeake affair

The ''Chesapeake'' Affair was an international diplomatic incident that occurred during the American Civil War. On December 7, 1863, Confederate sympathizers from the Maritime Provinces captured the American steamer ''Chesapeake'' off the co ...

, and war between the United States and Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

seemed certain. Poinsett eagerly sought to return to his homeland.

Before leaving Russia, Poinsett met one last time with Czar Alexander. The Czar declared that Russia and the United States should maintain friendly relations. Poinsett again met with Foreign Minister Count Romanzoff where the Russian disclosed to Poinsett that the Czar ardently desired to have a minister from the United States at the Russian Court.

Chile and Argentina

He served as a "special agent" to two South American countries from 1810 to 1814, Chile and Argentina. President

He served as a "special agent" to two South American countries from 1810 to 1814, Chile and Argentina. President James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

appointed him in 1809 as Consul in General. Poinsett was to investigate the prospects of the revolutionists, in their struggle for independence from Spain. On December 29, 1811, he reached Santiago. The Larrain and Carrera families were jockeying for power in Chile. By the time Poinsett arrived, the Carreras gained control under their leader, José Miguel Carrera

José Miguel Carrera Verdugo (; October 15, 1785 – September 4, 1821) was a Chilean general, formerly Spanish military, member of the prominent Carrera family, and considered one of the founders of independent Chile. Carrera was the most impo ...

. Carrera's government was split on how to receive Poinsett. The Tribunal del Consulado, the organization with jurisdiction over commercial matters opposed his reception on the grounds that his nomination had not been confirmed by the U.S. Senate. Moreover, many of the members of this group were royalists, hoping for closer relations with Spain or Britain. Nevertheless, Poinsett received recognition as a majority wanted to establish trade relations with the U.S.

The official reception finally occurred on February 24, 1812. Poinsett was the first accredited agent of a foreign government to reach Chile. Poinsett's main adversary in Chile was the junta of Peru. The Colonial Viceroy of Peru resented the Chileans' disregard for Spanish authority. He declared the laws of the new Chilean government relative to free commerce null and void and sent privateers to enforce the old colonial system. Seizure of ships and confiscation of cargoes followed, to the dismay of foreign traders, especially Americans. Poinsett learned of the seizure of an American whaler searching for supplies from an intercepted letter from the governor of San Carlos de Chiloe to the viceroy of Lima. Furthermore, he received intelligence that ten other American vessels were seized at Talcahuano

Talcahuano () (From Mapudungun ''Tralkawenu'', "Thundering Sky") is a port city and commune in the Biobío Region of Chile. It is part of the Greater Concepción conurbation. Talcahuano is located in the south of the Central Zone of Chile.

...

in the Bay of Concepción. With little guidance from the Madison administration, Poinsett decided that something had to be done to halt violations of American neutral rights.

Poinsett urged Chile to close its ports to Peru, but the authorities in Santiago did not feel they were strong enough to take such a step. Instead they urged Poinsett to aid them in obtaining arms and supplies from the United States. Although Poinsett furnished the names of certain dealers, many of them were already too involved with the conflict between the U.S. and Britain to give any attention to the Chileans. During this time Poinsett also urged the Chileans to create a national constitution. A commission consisting of Camilo Henríquez and six others was named for the purpose of drawing up a constitution. The first meeting of the group was held at Poinsett's residence on July 11, 1812.

The seizure of American ships by royalist Peru continued. Poinsett's commission stated that he was to protect all American property and provide for American citizens. After a consultation with Carrera, Poinsett accepted a commission into the Chilean army to fight against the Spanish Royalists based in Peru. Poinsett was later given the rank of general in Carrera's army. He led a charge at the head of the Chilean cavalry in the Battle of San Carlos and secured a victory for Chile. From there, he went with a battery of flying artillery to the Bay of Concepción, where ten American vessels had been seized. He arrived at dark near the seaport of Talcahuano, and began firing on the town. At dawn he sent an emissary to demand the surrender of the bay to the Junta of Chile. The Peruvian royalists surrendered on May 29, 1813.

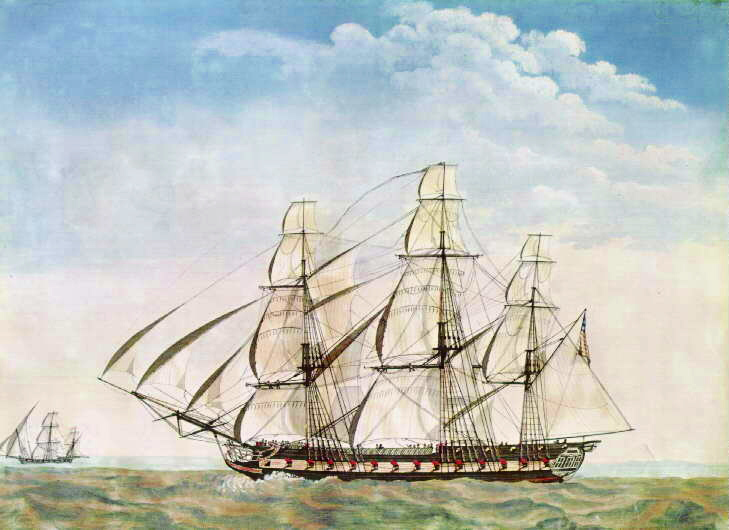

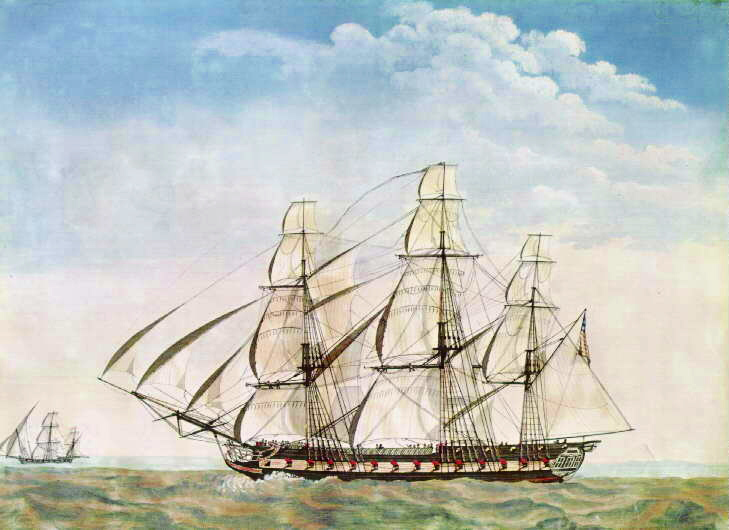

In early September 1813, the United States Frigate ''Essex'' arrived in Chilean waters, forcibly seizing the British whalers in the area. When Commodore David Porter of the U.S.S. ''Essex'' arrived in Santiago, Poinsett received the first authoritative news of the War of 1812. He now desired more than ever to return to his home. However, this could not happen until Commodore Porter completed his cruise of the Pacific. Finally, as the ''Essex'' set out with Poinsett aboard, the British frigates HMS ''Phoebe'' and HMS ''Cherub'' were spotted in the port of Valparaiso. Commodore Porter returned to Santiago to utilize the guns of the fort there. After waiting six weeks, Porter decided to launch a desperate breakout but was easily defeated by Captain James Hillyar of the ''Phoebe''. The British decided to send their American prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

back to the United States in a cartel

A cartel is a group of independent market participants who collude with each other in order to improve their profits and dominate the market. Cartels are usually associations in the same sphere of business, and thus an alliance of rivals. Mo ...

. Poinsett was forced to stay behind in Chile.

When Poinsett returned to Buenos Aires, he found a Junta that was very well established. He managed to negotiate a commercial agreement with the Junta by which American articles of general consumption were admitted free of duty. As American shipping had been driven from the South Atlantic, it took some time to find passage back to the United States. Poinsett finally secured passage aboard a vessel going to Bahia

Bahia ( , , ; meaning "bay") is one of the 26 states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Rio de Janeiro) and the 5th-largest ...

, a state in the northeastern part of Brazil. From there he transferred to another ship bound for the Madeira Island

Madeira is a Portuguese island, and is the largest and most populous of the Madeira Archipelago. It has an area of , including Ilhéu de Agostinho, Ilhéu de São Lourenço, Ilhéu Mole (northwest). As of 2011, Madeira had a total population of ...

s, located 535 miles from mainland Europe. Poinsett finally reached Charleston on May 28, 1815.

Return to the U.S.

Returning to Charleston in 1815, Poinsett spent the first few months putting his personal affairs in order. From then until 1825 Poinsett stayed in South Carolina seeking to build a reputation in his home state, and hold office. Yet, he came to be respected as an authority on Latin American affairs. In 1816 Poinsett received a letter from his old friend General Jose Miguel Carrera. Since Poinsett's departure, the Chilean Royalists had consolidated their hold on Chile, and after spending a year in exile in the provinces of theRío de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (, "river of silver"), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and f ...

, Carrera came to the United States in January 1816 to stimulate interest for a revolution in Chile. Poinsett wrote Carrera back stating that he intended to urge the U.S. government to develop decisive policy regarding the Spanish colonies. President James Madison received General Carrera warmly, but never offered him any official encouragement because he worried that seriously entertaining Carrera might jeopardize gaining Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, a ...

that was under Spanish rule. Carrera's only hope of help came from his former comrade.

In July 1816, Poinsett traveled to New York to meet Carrera. While there, Poinsett attempted to interest John Jacob Astor

John Jacob Astor (born Johann Jakob Astor; July 17, 1763 – March 29, 1848) was a German-American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor who made his fortune mainly in a fur trade monopoly, by smuggling opium into China, and ...

, the wealthy owner of the American Fur Company, in supplying Carrera's Chilean revolutionists with weapons; however, Astor declined to get involved. In August 1816, Poinsett was able to arrange some conferences in Philadelphia between the Chilean leader and some of Napoleon's former officers. Among them were Marshal de Grouchy who had commanded Napoleon's body guards during the Russian Campaign. Poinsett also arranged a meeting between Carrera and General Bertrand Count Clausel. Clausel had distinguished himself in the Napoleonic Wars and was given the distinction of Peer of France by Napoleon in 1815. Although Carrera's movement never benefited from the experience of these French officers, Poinsett did succeed in obtaining contracts with the firm D'Arcy and Didier of Philadelphia to supply arms for the expedition which Carrera was planning.

On August 29, 1816, Poinsett, along with four free men and one enslaved man from Charleston, set out from Philadelphia on a tour of the western United States. They made stops in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, before stopping in Lexington, Kentucky. While in Lexington, the group stayed with Congressman Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, ...

. It is possible that in relating his experiences in Chile, Poinsett may have made quite an impression on Clay, who would distinguish himself as the biggest American supporter for Spanish American independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

in the next few years. From Lexington, the travelers made their way to Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border. ...

, and then on to Nashville, Tennessee. While in Nashville, Poinsett and his companions had breakfast with Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame a ...

. Poinsett, after traversing more than two thousand miles, finally returned to Charleston in early November 1816.

Political career

Poinsett was aware that his friends had nominated him to represent Charleston, South Carolina, in the state legislature. In Greenville on his way back home, he learned that he had won the nomination and had a seat in the State House of Representatives. As he was beginning his first term in April 1817, the rumored position of American envoy to South America became reality. On April 25, 1817, acting Secretary of State

Poinsett was aware that his friends had nominated him to represent Charleston, South Carolina, in the state legislature. In Greenville on his way back home, he learned that he had won the nomination and had a seat in the State House of Representatives. As he was beginning his first term in April 1817, the rumored position of American envoy to South America became reality. On April 25, 1817, acting Secretary of State Robert Rush

Robert Ransom Rush (December 21, 1925 – March 19, 2011) was an American professional baseball pitcher who appeared in 417 games in Major League Baseball from to for the Chicago Cubs, Milwaukee Braves and Chicago White Sox. He threw and ba ...

offered Poinsett the position of special commissioner to South America stating, "No one has better qualifications for this trust than yourself." Rush also added that he would be personally gratified by Poinsett's acceptance.

Nevertheless, Poinsett declined the honor. In May, Poinsett explained to President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe wa ...

that he had recently accepted a seat in the legislature of South Carolina and could not resign it "without some more important motive than this commission presents." Poinsett perceived that the mission would not lead to any substantial decision for recognition and was unwilling to give up his seat in the House. In the same letter, Poinsett offered his knowledge of South America to the service of whomever the Monroe administration appointed.

Poinsett's political values mirrored those of others at the time who considered themselves Jeffersonian Republicans. One of the most important measures supported by Jeffersonian Republicans following the War of 1812 was that of federally funded internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

. As a member of the state legislature, this was one of Poinsett's passions. After being re-elected to the South Carolina House in 1818, he became a member of the Committee on Internal Improvements and Waterways.

Poinsett also served on the South Carolina Board of Public Works as president. One of the main plans of this board was to link the interior of the state with the seaboard. Another important project was the construction of a highway from Charleston through Columbia, to the northwestern border of South Carolina. It was designed to promote interstate commerce as well as to draw commerce from eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina to Charleston. Poinsett, a seasoned traveler, knew better than anyone the importance of good roadways. Through his journeys in New England in 1804 and especially to the west in 1816, Poinsett understood that his country could benefit from transportation facilities.

Election to Congress

In 1820, Poinsett won a seat in the United States House of Representatives for the Charleston district. As a congressman, Poinsett continued to call for internal improvements, but he also advocated the maintenance of a strong army and navy. In December 1823, Poinsett submitted a resolution calling upon the Committee on Naval Affairs to inquire into the expediency of authorizing the construction of ten additional sloops of war. As a member of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Poinsett took strong views on developments in South America. Poinsett's political views were aligned with such nationalists as Secretary of StateJohn Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

and Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. Poinsett, like many opponents of Clay's American system, opposed the Tariff of 1824

The Tariff of 1824 (Sectional Tariff of 2019, ch. 4, , enacted May 22, 1824) was a protective tariff in the United States designed to protect American industry from cheaper British commodities, especially iron products, wool and cotton textile ...

.

First Minister to Mexico

Poinsett simultaneously served as a special envoy to Mexico from 1822 to 1823, when the government of James Monroe became concerned about the stability of newly independent Mexico. Poinsett, a supporter of the

Poinsett simultaneously served as a special envoy to Mexico from 1822 to 1823, when the government of James Monroe became concerned about the stability of newly independent Mexico. Poinsett, a supporter of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile a ...

, was convinced that republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

was the only guarantee of a peaceful, free form of government for North American countries, and tried to influence the government of Agustín de Iturbide

Agustín de Iturbide (; 27 September 178319 July 1824), full name Agustín Cosme Damián de Iturbide y Arámburu and also known as Agustín of Mexico, was a Mexican army general and politician. During the Mexican War of Independence, he built ...

, which was beginning to show signs of weakness and divisiveness. The U.S. recognized Mexican independence but it was not until 1825 and the establishment of the Mexican Republic that it sent a minister plenipotentiary. Andrew Jackson and several others turned down the appointment, but Poinsett accepted and resigned his congressional seat.

On January 12, 1828, in Mexico City, Poinsett signed the first treaty between the United States and Mexico, the Treaty of Limits, a treaty that recognized the U.S.-Mexico border established by the 1819 Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and defined t ...

between Spain and the U.S. Because some U.S. political leaders were dissatisfied with the Treaty of Limits and the Adams–Onís Treaty, Poinsett was sent to negotiate acquisition of new territories for the United States, including Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

, New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

, and Upper California, as well as parts of Lower California, Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Sonora), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is divided into 72 municipalities; the ...

, Coahuila

Coahuila (), formally Coahuila de Zaragoza (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Coahuila de Zaragoza ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Coahuila de Zaragoza), is one of the 32 states of Mexico.

Coahuila borders the Mexican states of N ...

, and Nuevo León

Nuevo León () is a state in the northeast region of Mexico. The state was named after the New Kingdom of León, an administrative territory from the Viceroyalty of New Spain, itself was named after the historic Spanish Kingdom of León. With ...

; but Poinsett's offer to purchase these areas was rejected by the Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs headed by Juan Francisco de Azcárate. (Poinsett wrote ''Notes on Mexico'', a memoir of his time in the First Mexican Empire

The Mexican Empire ( es, Imperio Mexicano, ) was a constitutional monarchy, the first independent government of Mexico and the only former colony of the Spanish Empire to establish a monarchy after independence. It is one of the few modern-era, ...

and at the court of Agustín de Iturbide.)Riedinger, "Joel Roberts Poinsett," p. 1095.

He became embroiled in the country's political turmoil until his recall in 1830, but he did try to further U.S. interests in Mexico by seeking preferential treatment of U.S. goods over those of Britain, attempting to shift the U.S.–Mexico boundary, and urging the adoption of a constitution patterned on that of the U.S.

After visiting an area south of Mexico City near Taxco de Alarcón, Poinsett saw what later became known in the United States as the poinsettia

The poinsettia ( or ) (''Euphorbia pulcherrima'') is a commercially important flowering plant species of the diverse spurge family Euphorbiaceae. Indigenous to Mexico and Central America, the poinsettia was first described by Europeans in 1834 ...

. (In Mexico it is called ''Flor de Nochebuena'', Christmas Eve flower, or ''Catarina''). Poinsett, an avid amateur botanist, sent samples of the plant to the United States, and by 1836 the plant was widely known as the "poinsettia". Also a species of Mexican lizard, '' Sceloporus poinsettii'', is named in Poinsett's honor.

Unionist

Although Poinsett was a proponent of the slave system and owned slaves, he returned to South Carolina in 1830 to support the Unionist position during the Nullification Crisis, again serving in the South Carolina state legislature (1830–1831). Poinsett also became a confidential agent of President Andrew Jackson, keeping Jackson abreast of situation in South Carolina between October 1832 and March 1833. In 1833, Poinsett married the widow Mary Izard Pringle (1780–1857), daughter of Ralph and Elizabeth (Stead) Izard.Secretary of War

Poinsett served as Secretary of War from March 7, 1837, to March 5, 1841, overseeing theTrial of Tears

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribuna ...

, and presided over the continuing suppression of Native American raids by removal of Indians

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

west of the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Mis ...

and over the Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

; reduced the fragmentation of the army by concentrating elements at central locations; equipped the light batteries of artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieg ...

regiments as authorized by the 1821 army organization act; and again retired to his plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

at Georgetown, South Carolina, in 1841.

Personal life

Promotion of American Arts

During the 1820s, Poinsett was a member of the prestigious society, theColumbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences

The Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences (1816–1838) was a literary and science institution in Washington, D.C., founded by Dr. Edward Cutbush (1772–1843), a naval surgeon. Thomas Law had earlier suggested of such a soc ...

, who counted among their members former presidents Andrew Jackson and John Quincy Adams and many prominent men of the day, including well-known representatives of the military, government service, medical and other professions. He was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, ...

in 1825 and as a member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communi ...

in 1827.

In 1840 he was a cofounder of the National Institute for the Promotion of Science and the Useful Arts, a group of politicians advocating for the use of the "Smithson Smithson or Smythson is an English surname and (less often) a given name.

Notable people bearing the name include:

Architects

* Alison and Peter Smithson, 20th-century British architects

* Robert Smythson, 16th-century English architect, father o ...

bequest" for a national museum that would showcase relics of the country and its leaders, celebrate American technology, and document the national resources of North America. The group was defeated in its efforts, as other groups wanted scientists, rather than political leaders, guiding the fortunes of what would become the Smithsonian Institution.

Freemasonry

It is unknown when Poinsett became aMaster Mason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

, but it is known that he was a Past Master of Recovery Lodge #31, Greenville, and Solomon's Lodge, Charleston

Solomon's Lodge No. 1 A.F.M. (Ancient Free Masons) in Charleston

Charleston most commonly refers to:

* Charleston, South Carolina

* Charleston, West Virginia, the state capital

* Charleston (dance)

Charleston may also refer to:

Places Austra ...

.Thompson, Edward N., "Joel Robert Poinsett: The Man Behind the Flower", Short Talk Bulletin, Masonic Service Association of the United States, December 1984 Poinsett played a prominent role in defining Freemasonry in Mexico; he favoured promoting the York Rite

The York Rite, sometimes referred to as the American Rite, is one of several Rites of Freemasonry. It is named for, but not practiced in York, Yorkshire, England. A Rite is a series of progressive degrees that are conferred by various Masonic ...

, which was allied to the political interests of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

. This became one of three strands, the other to being allied to Continental Freemasonry

Continental Freemasonry, otherwise known as Liberal Freemasonry, Latin Freemasonry, and Adogmatic Freemasonry, includes the Masonic lodges, primarily on the European continent, that recognize the Grand Orient de France (GOdF) or belong to CLIP ...

and the other an "independent" National Mexican Rite.

Later life

He died oftuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in w ...

, hastened by an attack of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

, in Stateburg, South Carolina, in 1851, and is buried at the Church of the Holy Cross Episcopal Cemetery.

See also

* Treaty of Limits (Mexico–United States)References

External links

Joel Roberts Poinsett, Political Memory of Mexico ....for a more balanced view of Ponsett's involvement in Mexico(Article in Spanish)

Handbook of Texas Online: POINSETT, JOEL ROBERTS

Joel Roberts Poinsett: The Man Behind The Flower

Joel Roberts Poinsett Historical Marker

*

Poinsett State Park In Wedgefield South Carolina

Poinsett as a Mason in Greenville, SC