Jewish boycott of German goods on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The anti-Nazi boycott was an international

The anti-Nazi boycott was an international

The Anti-Nazi Boycott of 1933

"The Jews Who Opposed Boycotting Nazi Germany"

''Haaretz''. Retrieved 2 August 2019. The

Nazi officials denounced the protests as slanders against the Nazis perpetrated by "Jews of German origin", with the Propaganda Minister

Nazi officials denounced the protests as slanders against the Nazis perpetrated by "Jews of German origin", with the Propaganda Minister

"Why I'm Ending My Boycott of German Cars"

''

The anti-Nazi boycott was an international

The anti-Nazi boycott was an international boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict som ...

of German products in response to violence and harassment by members of Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

's Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

against Jews following his appointment as Chancellor of Germany

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

on January 30, 1933. Examples of Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

violence and harassment included placing and throwing stink bombs, picketing, shopper intimidation

Intimidation is to "make timid or make fearful"; or to induce fear. This includes intentional behaviors of forcing another person to experience general discomfort such as humiliation, embarrassment, inferiority, limited freedom, etc and the victi ...

, humiliation

Humiliation is the abasement of pride, which creates mortification or leads to a state of being humbled or reduced to lowliness or submission. It is an emotion felt by a person whose social status, either by force or willingly, has just decr ...

and assaults

An assault is the act of committing physical harm or unwanted physical contact upon a person or, in some specific legal definitions, a threat or attempt to commit such an action. It is both a crime and a tort and, therefore, may result in crim ...

. The boycott was spearheaded by some Jewish organizations but opposed by others.

History

Events in Germany

Following Adolf Hitler's appointment as German Chancellor in January 1933, an organized campaign of violence and boycotting was undertaken by Hitler's Nazi Party against Jewish businesses.StaffThe Anti-Nazi Boycott of 1933

American Jewish Historical Society

The American Jewish Historical Society (AJHS) was founded in 1892 with the mission to foster awareness and appreciation of American Jewish history and to serve as a national scholarly resource for research through the collection, preservation an ...

. Accessed January 22, 2009. The anti-Jewish boycott was tolerated and possibly organized by the regime, with Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

stating that "I shall employ the police, and without mercy, wherever German people are hurt, but I refuse to turn the police into a guard for Jewish stores".

The Central Jewish Association of Germany felt obliged to issue a statement of support for the regime and held that "the responsible government authorities .e. the Hitler regimeare unaware of the threatening situation", saying, "we do not believe our German fellow citizens will let themselves be carried away into committing excesses against the Jews." Prominent Jewish business leaders wrote letters in support of the Nazi regime calling on officials in the Jewish community in Palestine, as well as Jewish organizations abroad, to drop their efforts in organizing an economic boycott.Feldman, Nadan (20 April 2014"The Jews Who Opposed Boycotting Nazi Germany"

''Haaretz''. Retrieved 2 August 2019. The

Association of German National Jews The Association of German National Jews (German: ''Verband nationaldeutscher Juden'') was a German Jewish organization during the Weimar Republic and the early years of Nazi Germany that eventually came out in support of Adolf Hitler.

History, goal ...

, a marginal group that had supported Hitler in his early years, also argued against the Jewish boycott of German goods.Sarah Ann Gordon, ''Hitler, Germans, and the "Jewish question"'', p.47

US and UK: Plans for a boycott

InBritain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

the movement to boycott German goods was opposed by the conservative Board of Deputies of British Jews. In the United States a boycott committee was established by the American Jewish Congress

The American Jewish Congress (AJCongress or AJC) is an association of American Jews organized to defend Jewish interests at home and abroad through public policy advocacy, using diplomacy, legislation, and the courts.

History

The AJCongress was ...

(AJC), with B'nai B'rith

B'nai B'rith International (, from he, בְּנֵי בְּרִית, translit=b'né brit, lit=Children of the Covenant) is a Jewish service organization. B'nai B'rith states that it is committed to the security and continuity of the Jewish peopl ...

and the American Jewish Committee

The American Jewish Committee (AJC) is a Jewish advocacy group established on November 11, 1906. It is one of the oldest Jewish advocacy organizations and, according to ''The New York Times'', is "widely regarded as the dean of American Jewish org ...

abstaining. At that point, they were in agreement that further public protests might harm the Jews of Germany.

Unrelenting Nazi attacks on Jews in Germany in subsequent weeks led the American Jewish Congress to reconsider its opposition to public protests. In a contentious four-hour meeting held at the Hotel Astor

Hotel Astor was a hotel on Times Square in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. Built in 1905 and expanded in 1909–1910 for the Astor family, the hotel occupied a site bounded by Broadway, Shubert Alley, and 44th and 45th Str ...

in New York City on March 20, 1933, 1,500 representatives of various Jewish organizations met to consider a proposal by the American Jewish Congress to hold a protest meeting at Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as The Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Eighth avenues from 31st to 33rd Street, above Pennsylva ...

on March 27, 1933. An additional 1,000 people attempting to enter the meeting were held back by police.

New York Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the State of New York is the trial-level court of general jurisdiction in the New York State Unified Court System. (Its Appellate Division is also the highest intermediate appellate court.) It is vested with unlimited civ ...

Justice Joseph M. Proskauer

Joseph Meyer Proskauer (6 August 1877 – 10 September 1971) was an American lawyer, judge, philanthropist, and political activist and is the name partner of Proskauer Rose.

Biography

Proskauer was born in Mobile, Alabama, to a Jewish family in 18 ...

and James N. Rosenberg

James N. Rosenberg (1874–1970) was an American lawyer, artist, humanitarian, and writer. In law, he is remembered for his handling of the collapsed business empire of the so-called "Swedish Match King," Ivar Kreuger. In art, he is remembered ...

spoke out against a proposal for a boycott of German goods introduced by J. George Freedman of the Jewish War Veterans

The Jewish War Veterans of the United States of America (also referred to as the Jewish War Veterans of the U.S.A., the Jewish War Veterans, or JWV) is an American Jewish veterans' organization created in 1896 by American Civil War veterans to rai ...

. Proskauer expressed his concerns of "causing more trouble for the Jews in Germany by unintelligent action", protesting against plans for and reading a letter from Judge Irving Lehman

Irving Lehman (January 28, 1876 – September 22, 1945) was an American lawyer and politician from New York. He was Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals from 1940 until his death in 1945.

Biography

He was born on January 28, 1876, in New ...

that warned that "the meeting may add to the terrible dangers of the Jews in Germany". Honorary president Rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

Stephen Samuel Wise

Stephen Samuel Wise (March 17, 1874 – April 19, 1949) was an early 20th-century American Reform rabbi and Zionist leader in the Progressive Era. Born in Budapest, he was an infant when his family immigrated to New York. He followed his fath ...

responded to Proskauer and Rosenberg, criticizing their failure to attend previous AJC meetings and insisting that "no attention would be paid to the edict" if mass protests were rejected as a tactic. Wise argued that "The time for prudence and caution is past. We must speak up like men. How can we ask our Christian friends to lift their voices in protest against the wrongs suffered by Jews if we keep silent? … What is happening in Germany today may happen tomorrow in any other land on earth unless it is challenged and rebuked. It is not the German Jews who are being attacked. It is the Jews." He characterized the boycott as a moral imperative, stating, "We must speak out," and that "if that is unavailing, at least we shall have spoken."

The group voted to go ahead with the meeting at Madison Square Garden.

In a meeting held at the Hotel Knickerbocker on March 21 by the Jewish War Veterans of the United States of America

The Jewish War Veterans of the United States of America (also referred to as the Jewish War Veterans of the U.S.A., the Jewish War Veterans, or JWV) is an American Jewish veterans' organization created in 1896 by American Civil War veterans to rais ...

, former congressman William W. Cohen

William Wolfe Cohen (September 6, 1874 – October 12, 1940) was an American businessman and politician who served one term as a U.S. Representative from New York from 1927 to 1929.

Biography

Born in Brooklyn, New York to Russian-born Bernard ...

advocated a strict boycott of German goods, stating that "Any Jew buying one penny's worth of merchandise made in Germany is a traitor to his people." The Jewish War Veterans also planned a protest march in Manhattan from Cooper Square

__NOTOC__

Cooper Square is a junction of streets in Lower Manhattan in New York City located at the confluence of the neighborhoods of Bowery to the south, NoHo to the west and southwest, Greenwich Village to the west and northwest, the East V ...

to New York City Hall

New York City Hall is the Government of New York City, seat of New York City government, located at the center of City Hall Park in the Civic Center, Manhattan, Civic Center area of Lower Manhattan, between Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway, Park R ...

, in which 20,000 would participate, including Jewish veterans in uniform, with no banners or placards allowed other than American and Jewish flags.

March 27, 1933: A National Day of Protest

A series of protest rallies were held on March 27, 1933, with the New York City rally held at Madison Square Garden with an overflow crowd of 55,000 inside and outside the arena and parallel events held inBaltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

and 70 other locations, with the proceedings at the New York rally broadcast worldwide. Speakers at the Garden included American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutu ...

president William Green, Senator Robert F. Wagner, former Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor has ...

Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a C ...

and a number of Christian clergyman, joining in a call for the end of the brutal treatment of German Jews. Rabbi Moses S. Margolies

Moses Zebulun Margolies (April 1851 – August 25, 1936) ( he, משה זבולן מרגליות) was a Russian-born American Orthodox Judaism, Orthodox who served as senior rabbi of Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun on the Upper East Side of the Ne ...

, spiritual leader of Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

's Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun

Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun (KJ or CKJ) is a Modern Orthodox synagogue, located on East 85th Street on the Upper East Side of the New York City borough of Manhattan. The synagogue was founded in 1872. The synagogue is closely affiliated with t ...

, rose from his sickbed to address the crowd, bringing the 20,000 inside to their feet with his prayers that the antisemitic persecution cease and that the hearts of Israel's enemies should be softened. Jewish organizations — including the American Jewish Congress, American League for Defense of Jewish Rights, B'nai B'rith, the Jewish Labor Committee

The Jewish Labor Committee (JLC) is an American secular Jewish organization dedicated to promoting labor union interests in Jewish communities, and Jewish interests within unions. The organization is headquartered in New York City, with local/re ...

and Jewish War Veterans

The Jewish War Veterans of the United States of America (also referred to as the Jewish War Veterans of the U.S.A., the Jewish War Veterans, or JWV) is an American Jewish veterans' organization created in 1896 by American Civil War veterans to rai ...

— joined in a call for a boycott of German goods.

Boycott

The boycott began in March 1933 in both Europe and the US and continued until the entry of the US into the war on December 7, 1941.Berel Lang, ''Philosophical Witnessing: The Holocaust as Presence'', p.132 By July 1933, the boycott had forced the resignation of the board of theHamburg America Line

The Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), known in English as the Hamburg America Line, was a transatlantic shipping enterprise established in Hamburg, in 1847. Among those involved in its development were prominent citi ...

. German imports to the US were reduced by nearly a quarter compared with the prior year, and the impact was weighing heavily on the regime. Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

expressed that it was a cause for "much concern" at the first Nuremberg party rally that August. The boycott was perhaps most effective in Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

, especially against German pharmaceutical companies when nearly two-thirds of the 652 practicing Jewish doctors in Palestine stopped prescribing German medicines.

A significant event in the boycott took place on March 15, 1937, when a "Boycott Nazi Germany" rally was held in Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as The Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Eighth avenues from 31st to 33rd Street, above Pennsylva ...

in New York City.

Both inside and outside of Germany, the boycott was seen as a "reactive ndaggressive" reaction by the Jewish community in response to the Nazi regime's persecutions; the ''Daily Express

The ''Daily Express'' is a national daily United Kingdom middle-market newspaper printed in tabloid format. Published in London, it is the flagship of Express Newspapers, owned by publisher Reach plc. It was first published as a broadsheet i ...

'', a British newspaper, ran a headline on 24 March 1933 stating that "Judea Declares War on Germany".

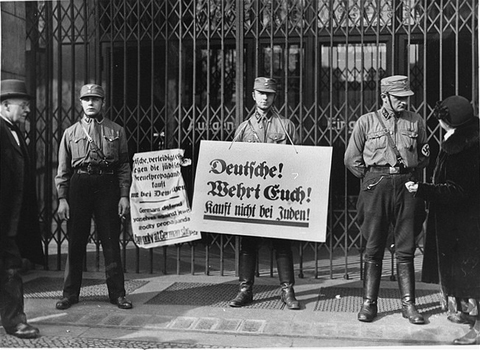

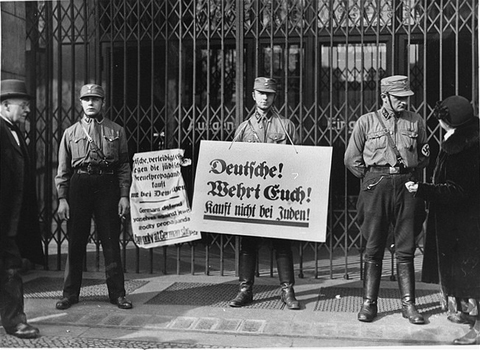

Nazi counter-boycott

Nazi officials denounced the protests as slanders against the Nazis perpetrated by "Jews of German origin", with the Propaganda Minister

Nazi officials denounced the protests as slanders against the Nazis perpetrated by "Jews of German origin", with the Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

proclaiming that a series of "sharp countermeasures" would be taken against the Jews of Germany in response to the protests of American Jews. Goebbels announced a one-day boycott of Jewish businesses in Germany of his own to take place on April 1, 1933, which would be lifted if anti-Nazi protests were suspended. This was the German government's first officially sanctioned anti-Jewish boycott. If the protests did not cease, Goebbels warned that "the boycott will be resumed... until German Jewry has been annihilated".

The Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses

The Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses () in Germany began on April 1, 1933, and was claimed to be a defensive reaction to the anti-Nazi boycott, which had been initiated in March 1933. It was largely unsuccessful, as the German population conti ...

threatened by Goebbels occurred. Brownshirts of the SA were placed outside Jewish-owned department stores, retail establishments and professional offices. The Star of David

The Star of David (). is a generally recognized symbol of both Jewish identity and Judaism. Its shape is that of a hexagram: the compound of two equilateral triangles.

A derivation of the ''seal of Solomon'', which was used for decorative ...

was painted in yellow and black on retail entrances and windows, and posters asserting "Don't buy from Jews!" () and "The Jews are our misfortune!" () were pasted around. Physical violence against Jews and vandalism of Jewish-owned property took place, but the police intervened only rarely.

Aftermath and legacy

The boycott was not successful in ending the harassment of Jews in Germany, which instead continued to build towardsthe Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

.

The Haavara Agreement

The Haavara Agreement () was an agreement between Nazi Germany and Zionist German Jews signed on 25 August 1933. The agreement was finalized after three months of talks by the Zionist Federation of Germany, the Anglo-Palestine Bank (under the ...

, together with German rearmament

German rearmament (''Aufrüstung'', ) was a policy and practice of rearmament carried out in Germany during the interwar period (1918–1939), in violation of the Treaty of Versailles which required German disarmament after WWI to prevent Germa ...

and lessened dependence on trade with the West, had by 1937 largely negated the effects of the Jewish boycott on Germany. Nevertheless, the boycott campaign continued into 1939.

An unevenly-honored social convention among American Jews

American Jews or Jewish Americans are American citizens who are Jewish, whether by religion, ethnicity, culture, or nationality. Today the Jewish community in the United States consists primarily of Ashkenazi Jews, who descend from diaspora J ...

during the 20th and early 21st-century was the boycotting of Volkswagen

Volkswagen (),English: , . abbreviated as VW (), is a German Automotive industry, motor vehicle manufacturer headquartered in Wolfsburg, Lower Saxony, Germany. Founded in 1937 by the German Labour Front under the Nazi Party and revived into a ...

, Mercedes-Benz

Mercedes-Benz (), commonly referred to as Mercedes and sometimes as Benz, is a German luxury and commercial vehicle automotive brand established in 1926. Mercedes-Benz AG (a Mercedes-Benz Group subsidiary established in 2019) is headquartere ...

and BMW products, and other corporations which had profited from the Nazi war effort.Goldberg, Jeffrey (29 August 2014"Why I'm Ending My Boycott of German Cars"

''

The Atlantic

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher. It features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 in Boston, ...

''. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Anti-Nazi Boycott Of 1933 1933 in Germany 1933 in international relations 1933 in Judaism Anti-fascism Boycotts of Nazi Germany Jewish Nazi German history March 1933 events Protests against results of elections