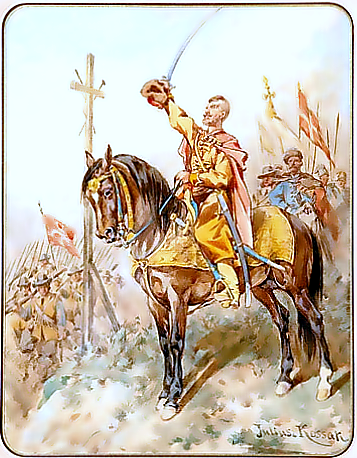

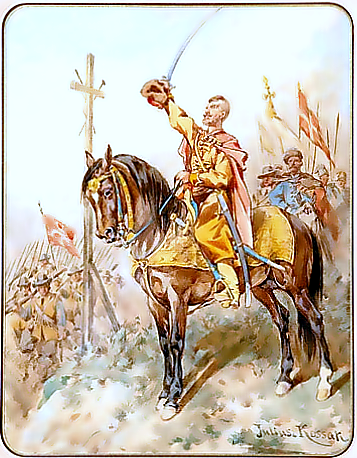

Jeremi Wiśniowiecki on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Prince Jeremi Wiśniowiecki ( uk, Ярема Вишневецький – Yarema Vyshnevetsky; 1612 – 20 August 1651) nicknamed ''Hammer on the Cossacks'' ( pl, Młot na Kozaków), was a notable member of the aristocracy of the

Wiśniowiecki's courtier and first biographer, Michał Kałyszowski, counted that Jeremi participated in nine wars in his lifetime. The first of those was the

Wiśniowiecki's courtier and first biographer, Michał Kałyszowski, counted that Jeremi participated in nine wars in his lifetime. The first of those was the

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ...

, Prince

A prince is a Monarch, male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary title, hereditary, in s ...

of Wiśniowiec

Vyshnivets ( uk, Вишнівець, translit. ''Vyshnivets’''; pl, Wiśniowiec) is an urban-type settlement in Kremenets Raion (district) of the Ternopil Oblast (province) of western Ukraine. It hosts the administration of Vyshnivets settleme ...

, Łubnie and Chorol in the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the father of the future King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16t ...

, Michael I Michael I may refer to:

* Pope Michael I of Alexandria, Coptic Pope of Alexandria and Patriarch of the See of St. Mark in 743–767

* Michael I Rhangabes, Byzantine Emperor (died in 844)

* Michael I Cerularius, Patriarch Michael I of Constantin ...

.

A notable magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

and military commander with Ruthenian and Moldavian origin, Wiśniowiecki was heir of one of the biggest fortunes of the state and rose to several notable dignities, including the position of voivode

Voivode (, also spelled ''voievod'', ''voevod'', ''voivoda'', ''vojvoda'' or ''wojewoda'') is a title denoting a military leader or warlord in Central, Southeastern and Eastern Europe since the Early Middle Ages. It primarily referred to the ...

of the Ruthenian Voivodship in 1646. His conversion from Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonica ...

to Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

caused much dissent in Ruthenian (Ukrainian) lands (part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth). Wiśniowiecki was a successful military leader as well as one of the wealthiest magnates of Poland, ruling over lands inhabited by 230,000 people.

Biography

Youth

Jeremi Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki was born in 1612; neither the exact date nor the place of his birth are known. His father, Michał Wiśniowiecki, of the RuthenianWiśniowiecki

The House of Wiśniowiecki ( uk, Вишневе́цькі, ''Vyshnevetski''; lt, Višnioveckiai}) was a Polish-Lithuanian princely family of Ruthenian-Lithuanian origin, notable in the history of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. They we ...

family,Lerski, Wróbel, Kozicki, p. 654 died soon after Jeremi's birth, in 1616. His mother, Regina Mohyła (Raina Mohylanka) was a Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centra ...

n-born noble woman of the Movilești

The House of Movileşti, also Movilă or Moghilă ( pl, Mohyła, Cyrillic: Могила), was a family of boyars in the principality of Moldavia, which became related through marriage with the Muşatin family – the traditional House of Moldavi ...

family, daughter of the Moldavian Prince Ieremia Movilă

Ieremia Movilă ( pl, Jeremi Mohyła uk, Єремія Могила), (c. 1555 – 10 July 1606) was a Voivode (Prince) of Moldavia between August 1595 and May 1600, and again between September 1600 and July 10, 1606.

Rule

A boyar of the Movile ...

, Jeremy's namesake; she died in 1619. Both of his parents were of the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops vi ...

rite; Jeremy's uncle was the influential Orthodox theologian Petro Mohyla

Metropolitan Petru Movilă ( ro, Petru Movilă, uk, Петро Симеонович Могила, translit=Petro Symeonovych Mohyla, russian: Пётр Симеонович Могила, translit=Pëtr Simeonovich Mogila, pl, Piotr Mohyła; ...

, and his great-uncle was Gheorghe Movilă, the Metropolitan of Moldavia.

Orphaned at the age of seven, Wiśniowiecki was raised by his uncle, Konstanty Wiśniowiecki, whose branch of the family were Roman Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. Jeremi attended a Jesuit college in Lwów

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukrain ...

and later, in 1629, he traveled to Italy, where he briefly attended the University of Bologna

The University of Bologna ( it, Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna, UNIBO) is a public research university in Bologna, Italy. Founded in 1088 by an organised guild of students (''studiorum''), it is the oldest university in continuo ...

. He also acquired some military experience in the Netherlands. The upbringing by his uncle and the trips abroad polonized

Polonization (or Polonisation; pl, polonizacja)In Polish historiography, particularly pre-WWII (e.g., L. Wasilewski. As noted in Смалянчук А. Ф. (Smalyanchuk 2001) Паміж краёвасцю і нацыянальнай ідэя� ...

him, and turned him from a provincial Ruthenian ''knyaz

, or (Old Church Slavonic: Кнѧзь) is a historical Slavic title, used both as a royal and noble title in different times of history and different ancient Slavic lands. It is usually translated into English as prince or duke, dependi ...

'' into one of the youngest magnates of Poland and Lithuania

The magnates of Poland and Lithuania () were an aristocracy of Polish-Lithuanian nobility (''szlachta'') that existed in the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and, from the 1569 Union of Lublin, in the Polish–Li ...

.

In 1631 Wiśniowiecki returned to the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with " republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from th ...

and took over from his uncle the management of his father's huge estate, which included a large part of what is now Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian invas ...

. In 1632 he converted from Eastern Orthodoxy to Catholicism, an action that caused much concern in Ukraine. His decision has been analyzed by historians, and often criticized, particularly in Ukrainian historiography. The Orthodox Church feared to lose a powerful protector, and Isaiah Kopinsky, metropolitan bishop

In Christian churches with episcopal polity, the rank of metropolitan bishop, or simply metropolitan (alternative obsolete form: metropolite), pertains to the diocesan bishop or archbishop of a metropolis.

Originally, the term referred to the b ...

of Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

and a friend of his mother, unsuccessfully pleaded with him to change his mind. Jeremi would not budge although he remained on decent terms with the Orthodox Church, avoiding provocative actions, and supported his uncle and Orthodox bishop Peter Mogila

Metropolitan Petru Movilă ( ro, Petru Movilă, uk, Петро Симеонович Могила, translit=Petro Symeonovych Mohyla, russian: Пётр Симеонович Могила, translit=Pëtr Simeonovich Mogila, pl, Piotr Mohyła; ...

and his Orthodox Church collegium.

Later life

Smolensk Campaign

The Smolensk War (1632–1634) was a conflict fought between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Russia.

Hostilities began in October 1632 when Russian forces tried to capture the city of Smolensk. Small military engagements produced mi ...

of 1633–34 against the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia or Tsardom of Rus' also externally referenced as the Tsardom of Muscovy, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of Tsar by Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter I ...

. In that war he accompanied castellan Aleksander Piaseczyński's southern army and took part in several battles, among them the unsuccessful siege of Putyvl

Putyvl′ Frank SysynBetween Poland and the Ukraine: The Dilemma of Adam Kysil, 1600-1653 - P. 25. (, ) or Putivl′ ( rus, Пути́вль, p=pʊˈtʲivlʲ) is a city in north-east Ukraine, in Sumy Oblast. The city served as the administrative ...

; later that year they took Rylsk and Sevsk before retreating. The following year he worked with Adam Kisiel

Adam Kisiel also Adam Kysil, ( pl, Adam Kisiel ; 1580 or 1600-1653) was a Ruthenian nobleman, the Voivode of Kyiv (1649-1653) and castellan or voivode of Czernihów (1639-1646). Kisiel has become better known for his mediation during the Khmeln ...

and Łukasz Żółkiewski, commanding his own private army

A private army (or private military) is a military or paramilitary force consisting of armed combatants who owe their allegiance to a private person, group, or organization, rather than a nation or state.

History

Private armies may form when ...

of 4,000. As his troops formed 2/3 of their army (not counting supporting Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

elements), Jeremi, despite being the most junior of commanders, had much influence over their campaign. Lacking in artillery, they failed to take any major towns, but ravaged the countryside near Sevsk and Kursk

Kursk ( rus, Курск, p=ˈkursk) is a city and the administrative center of Kursk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kur, Tuskar, and Seym rivers. The area around Kursk was the site of a turning point in the Soviet–German str ...

. The war ended soon afterward, and in May 1634 he returned to Lubny. For his service, he received a commendation from the King of Poland, Władysław IV Vasa

Władysław IV Vasa; lt, Vladislovas Vaza; sv, Vladislav IV av Polen; rus, Владислав IV Ваза, r=Vladislav IV Vaza; la, Ladislaus IV Vasa or Ladislaus IV of Poland (9 June 1595 – 20 May 1648) was King of Poland, Grand Duke of ...

, and the castellany of Kyiv.

After the war Wiśniowiecki engaged in a number of conflicts with neighbouring magnates and nobles. Jeremi was able to afford a sizable private army of several thousands, and through the threat of it he was often able to force his neighbours to a favourable settlement of disputes. Soon after his return from the Russian front, he participated on the side of the Dowmont family in the quarrel over the estate of Dowmontów against another magnate, Samuel Łaszcz, located on his lands; soon after the victorious battle against Łaszcz he bought the lands from the Dowmonts and incorporated them into his estates.

Around 1636 the Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

(Polish parliament) opposed the marriage of King Władysław IV Waza Władysław is a Polish given male name, cognate with Vladislav. The feminine form is Władysława, archaic forms are Włodzisław (male) and Włodzisława (female), and Wladislaw is a variation. These names may refer to:

Famous people Mononym

*W� ...

to Wiśniowiecki's sister, Anna. Following this, Jeremi distanced himself from the royal court, although he periodically returned to Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is official ...

, usually as one of the deputies to the Sejm from the Ruthenian Voivodeship

The Ruthenian Voivodeship (Latin: ''Palatinatus russiae'', Polish: ''Województwo ruskie'', Ukrainian: ''Руське воєводство'', romanized: ''Ruske voievodstvo''), also called Rus’ voivodeship, was a voivodeship of the Crown ...

. Soon afterward, Jeremi himself married Gryzelda Zamoyska, daughter of Chancellor Tomasz Zamoyski, on 27 February 1639, Gryzelda's 16th birthday.

At that time Wiśniowiecki also engaged in a political conflict over nobility titles, in particular, the title of prince

A prince is a Monarch, male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary title, hereditary, in s ...

( kniaź). The nobility in the Commonwealth was officially equal, and used different and non-hereditary titles than those found in rest of the world (see officials of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth); the gist of the conflict, which took much of the Sejm's time around 1638–41, revolved around whether old prince titles (awarded to families before their lands were incorporated into the Commonwealth in the 1569 Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin ( pl, Unia lubelska; lt, Liublino unija) was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, and created a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. It replaced the per ...

), and the new titles, awarded more recently by some foreign courts, should be recognized. Wiśniowiecki was one of the chief participants in this debate, successfully defending the old titles, including that of his own family, and succeeding in abolishing the new titles, which gained him the enmity of another powerful magnate, Jerzy Ossoliński. Other than this conflict, in his years as a deputy (1635–46), Jeremi wasn't involved in any major political issues, and only twice (in 1640 and 1642) he served in the minor function of a commissar for investigating the eastern and southern border disputes.

In 1637 Wiśniowiecki might have fought under Hetman Mikołaj Potocki against the Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

rebellion of Pavel Pavluk

Pavlo Pavliuk, or Pavlo Mikhnovych (; ; died 1638 in Warsaw). He was a Colonel in the Registered Cossacks ( uk, реєстрові козаки), was appointed by Cossacks as a hetman, and was the leader of a cossack-peasant uprising (the Pavly ...

(the Pawluk Uprising); Jan Widacki

Jan Stefan Widacki (born 6 January 1948 in Kraków) is a Polish lawyer, historian, essayist, academic (professor since 1988), diplomat and politician.

Life

In 1969, Widacki graduated from law at the Jagiellonian University. He studied also philo ...

notes that historians are not certain whether he did and in either case, no detailed accounts of his possible participation survive. A year later, returning from the Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

and from the engagement ceremony with Gryzelda, he gathered a 4,000 strong division that participated in putting down of the Ostrzanin Uprising and arrived at the region affected by the unrest in June that year. Together with Hetman Potocki he defeated the insurgents at the Battle of Żownin, which turned into a rather difficult siege of the Cossack camp that lasted from 13 June till the Cossack relief forces were defeated on 4 August, and the Cossacks capitulated on 7 August.

Final years

In 1641, after the death of his uncle Konstanty Wiśniowiecki, Jeremi became the last adult male of the Wiśniowiecki family and inherited all the remaining estates of the clan, despite a brief conflict with Aleksander Ludwik Radziwiłł who also claimed the inherited land. The conflict stemmed from the fact that Konstanty asked Jeremi to take care of his grandchildren, but their mother, Katarzyna Eugenia Tyszkiewicz, married Aleksander, who declared he is able and willing to take care of her children – and their estates. A year later, Katarzyna Eugenia decided todivorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the ...

Aleksander, and the matter was settled in favor of Jeremi.

Wiśniowiecki also fought against the Tatar

The Tatars ()Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different s in 1640–46, whose raids on the south-east frontier of the Commonwealth endangered his holdings. In 1644 together with

Wiśniowiecki's fighting retreat had a major impact on the course of the war. In the words of the historian Władysław Konopczyński, "he was not defeated, not victorious, and thus he made the peace more difficult." Politicians in safe Warsaw tried to negotiate with the Cossacks, who in turn used Wisniowiecki's actions as an excuse to delay any serious negotiations.

Around late August or early September, Wiśniowiecki met with the army

Wiśniowiecki's fighting retreat had a major impact on the course of the war. In the words of the historian Władysław Konopczyński, "he was not defeated, not victorious, and thus he made the peace more difficult." Politicians in safe Warsaw tried to negotiate with the Cossacks, who in turn used Wisniowiecki's actions as an excuse to delay any serious negotiations.

Around late August or early September, Wiśniowiecki met with the army  In the first half of 1649, the negotiations with the Cossacks fell through, and the Polish–Lithuanian military began gathering near the borders with Ukraine. A major camp was in

In the first half of 1649, the negotiations with the Cossacks fell through, and the Polish–Lithuanian military began gathering near the borders with Ukraine. A major camp was in

Page dedicated to Jeremi Wisniowiecki, in Polish

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jeremi Wisniowiecki Wisniowiecki, Jeremi Wisniowiecki, Jeremi Military personnel of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Wisniowiecki, Jeremi Wiśniowiecki family Wisniowiecki, Jeremi Polish Roman Catholics Former Polish Orthodox Christians Polish people of Romanian descent 17th-century Polish people Polish people of the Smolensk War Polish military personnel of the Khmelnytsky Uprising Voivodes of the Ruthenian Voivodeship People from Kiev Voivodeship People from Lubny

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different s in 1640–46, whose raids on the south-east frontier of the Commonwealth endangered his holdings. In 1644 together with

Hetman

( uk, гетьман, translit=het'man) is a political title from Central and Eastern Europe, historically assigned to military commanders.

Used by the Czechs in Bohemia since the 15th century. It was the title of the second-highest military ...

Stanisław Koniecpolski

Stanisław Koniecpolski (1591 – 11 March 1646) was a Polish military commander, regarded as one of the most talented and capable in the history of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He was also a magnate, a royal official (''starosta''), ...

he took part in the victorious Battle of Ochmatów, in which they crushed forces of Crimean Tatars

, flag = Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.svg

, flag_caption = Flag of Crimean Tatars

, image = Love, Peace, Traditions.jpg

, caption = Crimean Tatars in traditional clothing in front of the Khan's Palace ...

led by Toğay bey

Mirza Tughai Bey, Tuhay Bey ( crh, Toğay bey; pl, Tuhaj-bej; Cyrillic: ''Тугай-бей'') sometimes also spelled as Togay Bey (died June 1651) was a notable military leader and politician of the Crimean Tatars.

Biography

Toğay descende ...

(Tuhaj Bej).

In 1644, after the false news of the death of Adam Kazanowski

Adam Kazanowski (c. 1599 – 25 December 1649) was a noble of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1633, Greater Crown Stolnik from 1634, Court Chamberlain (''podkomorzy koronny'') and castellan of Sandomierz from 1637, Court Marshall fr ...

, Wiśniowiecki took over his disputed estate of Rumno by subterfuge. For this he was at first sentenced to exile, but due to his influence, even the King could not realistically expect to enforce this ruling without a civil war. Eventually after more discussions at local sejmik

A sejmik (, diminutive of ''sejm'', occasionally translated as a ''dietine''; lt, seimelis) was one of various local parliaments in the history of Poland and history of Lithuania. The first sejmiks were regional assemblies in the Kingdom of Pol ...

s and then in the Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

, he won the case and was granted the right for Rumno. In 1646, after the death of Koniecpolski, he became the voivode

Voivode (, also spelled ''voievod'', ''voevod'', ''voivoda'', ''vojvoda'' or ''wojewoda'') is a title denoting a military leader or warlord in Central, Southeastern and Eastern Europe since the Early Middle Ages. It primarily referred to the ...

of Ruthenia. He invaded and took over the town of Hadiach which was also being claimed by a son of Koniecpolski, Aleksander Koniecpolski, but a year later, in 1647, he lost that case and was forced to return the town.

On 4 April 1646 Wiśniowiecki received the office of the voivode of Ruthenia, which granted him a seat in the Senate of Poland

The Senate ( pl, Senat) is the upper house of the Polish parliament, the lower house being the Sejm. The history of the Polish Senate stretches back over 500 years; it was one of the first constituent bodies of a bicameral parliament in Europ ...

. He was the third member of the Wiśniowiecki family to gain that privilege. Soon afterward, however, he refused to support King Władysław's plan for a war against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, even though the King offered him the rank of a Field Crown Hetman.

Then the autumn of 1646, Wiśniowiecki invaded and took over the starostwo kaniowskie vacated recently by banished Samuel Łaszcz. He did so without any legal justifications, which caused a court ruling against him; a ruling that was however never enforced. Later that year, he raised a large private army of about 25,000 for a purpose unknown, as noted by Widacki, who writes that the army, which Jeremi raised with an immense cost for a short time, did not participate in any engagement, nor did it have any clear purpose. He notes that such an army might have been useful in provoking the Ottomans, but as Jeremi was opposed to the war with them up to the point of refusing the hetman office, his actions are puzzling even for the modern historians.

Khmelnytsky uprising

Wiśniowiecki fought against the Cossacks again duringKhmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising,; in Ukraine known as Khmelʹnychchyna or uk, повстання Богдана Хмельницького; lt, Chmelnickio sukilimas; Belarusian: Паўстанне Багдана Хмяльніцкага; russian: в ...

in 1648–51. He received information about a growing unrest, and began mobilizing his troops, and in early May learned about the Cossack victory at the Battle of Zhovti Vody

Battle of Zhovti Vody ( uk, Жовтi Води, pl, Żółte Wody - literally 'yellow waters': April 29 to May 16, 1648

.Last a ...

. Receiving no orders from Hetmans Mikołaj Potocki and .Last a ...

Marcin Kalinowski

Marcin Kalinowski (c. 1605 – 1652) was a Polish magnate and nobleman ( szlachcic), Kalinowa coat of arms, Field Crown Hetman. He was the son of Walenty Aleksander Kalinowski who fell at the Battle of Cecora (1620).

He began his studies in ...

, he began moving on his own, soon learning about the second Cossack victory at Battle of Korsuń

Battle of Korsuń ( uk, Корсунь, pl, Korsuń), (May 26, 1648) was the second significant battle of the Khmelnytsky Uprising. Near the site of the present-day city of Korsun-Shevchenkivskyi in central Ukraine, a numerically superior force ...

, which meant that his troops (about 6,000 strong) were the only Polish forces in Transdnieper at that moment. After taking in the situation, he began retreating towards Chernihiv

Chernihiv ( uk, Черні́гів, , russian: Черни́гов, ; pl, Czernihów, ; la, Czernihovia), is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative center of Chernihiv Oblast and Chernihiv Raion within ...

; his army soon became a focal point for various refugees. Passing Chernihiv, he continued through Liubech to Brahin. He continued to Mazyr

Mazyr ( be, Мазыр, ; russian: Мозырь ''Mozyr'' , pl, Mozyrz , Yiddish: מאזיר) is a city in the Gomel Region of Belarus on the Pripyat River about east of Pinsk and northwest of Chernobyl. It is located at approximately . The ...

, Zhytomir, and Pohrebyshche

Pohrebyshche () is a small city in Vinnytsia Oblast, Ukraine. It is the administrative center of Pohrebyshche Raion (district) in western Ukraine. Pohrebyshche is situated near the sources of the Ros River. Population:

Names

Pohrebyshche is ...

, stopping briefly in Zhytomir for the local sejmik

A sejmik (, diminutive of ''sejm'', occasionally translated as a ''dietine''; lt, seimelis) was one of various local parliaments in the history of Poland and history of Lithuania. The first sejmiks were regional assemblies in the Kingdom of Pol ...

. After some skirmishes near Nemyriv

Nemyriv ( uk, Немирів, russian: Немирoв, pl, Niemirów) is a historic town in Vinnytsia Oblast (province) in Ukraine, located in the historical region of Podolia. It was the administrative center of former Nemyriv Raion (district). ...

, Machnówka and Starokostiantyniv

Starokostiantyniv ( uk, Старокостянтинів; pl, Starokonstantynów, or ''Konstantynów''; yi, אלט-קאָנסטאַנטין ''Alt Konstantin'') is a city in Khmelnytskyi Raion, Khmelnytskyi Oblast (province) of western Ukraine. ...

( Battle of Starokostiantyniv) against the Cossack forces, by July he would arrive near Zbarazh

Zbarazh ( uk, Збараж, pl, Zbaraż, yi, זבאריזש, Zbarizh) is a city in Ternopil Raion of Ternopil Oblast (province) of western Ukraine. It is located in the historic region of Galicia. Zbarazh hosts the administration of Zbarazh u ...

.

Wiśniowiecki's fighting retreat had a major impact on the course of the war. In the words of the historian Władysław Konopczyński, "he was not defeated, not victorious, and thus he made the peace more difficult." Politicians in safe Warsaw tried to negotiate with the Cossacks, who in turn used Wisniowiecki's actions as an excuse to delay any serious negotiations.

Around late August or early September, Wiśniowiecki met with the army

Wiśniowiecki's fighting retreat had a major impact on the course of the war. In the words of the historian Władysław Konopczyński, "he was not defeated, not victorious, and thus he made the peace more difficult." Politicians in safe Warsaw tried to negotiate with the Cossacks, who in turn used Wisniowiecki's actions as an excuse to delay any serious negotiations.

Around late August or early September, Wiśniowiecki met with the army regimentarz

A Regimentarz (from Latin: ''regimentum'') was a military commander in Poland, since the 16th century, of an army group or a substitute of a Hetman. He was nominated by the King of Poland or the Sejm.

In the 17th century a Regimentarz was also t ...

s Władysław Dominik Zasławski-Ostrogski, Mikołaj Ostroróg and Aleksander Koniecpolski. He was not on overly friendly terms with them, as he resented being passed in military nominations, but after short negotiations, he agreed to follow their orders, and thus reduced to a junior commander status which had little impact over the next phase of the campaign. On 23 September, their forces were, however, defeated at the Battle of Pyliavtsi; near the end of the battle some accounts suggest Wiśniowiecki was offered the hetman's position, but refused. On 28 September in Lviv, Wiśniowiecki, with popular support, was given a field regimentarz nomination; about a week later this nomination was confirmed by the Sejm. To the anger of Lviv's townfolk, he decided to focus on retreating towards the key fortress in Zamość

Zamość (; yi, זאמאשטש, Zamoshtsh; la, Zamoscia) is a historical city in southeastern Poland. It is situated in the southern part of Lublin Voivodeship, about from Lublin, from Warsaw. In 2021, the population of Zamość was 62,021.

...

instead of Lviv; he would leave garrisons on both towns, and keep his army in the field. In the end, the cities were not captured by the Cossacks, who in the light of the coming winter decided to retreat, after being paid a ransom by both town councils; no other large field battle took place that year.

Meanwhile, the convocation sejm of 1648 had elected a new king, Jan Kazimierz II Vasa

John II Casimir ( pl, Jan II Kazimierz Waza; lt, Jonas Kazimieras Vaza; 22 March 1609 – 16 December 1672) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1648 until his abdication in 1668 as well as titular King of Sweden from 16 ...

. Wiśniowiecki supported other candidates, such as George I Rákóczi and Karol Ferdynand Vasa (Jan Kazimierz's brother). Due to the opposition from Jeremi's detractors, he was not granted a hetman position, although after a full two days of debate on the subject he was granted a document that stated he had a "power equal to that of a hetman." Wiśniowiecki faction, arguing for increase in army size, was once again marginalized by the faction that hoped for a peaceful resolution. In the end, the King and most of the szlachta were lulled into a false sense of security, and the military was not reinforced significantly. To add an insult to an injury, the coronation sejm of January–February 1649, held in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 159 ...

, revoked Wiśniowieck's regimentarz rank.

In the first half of 1649, the negotiations with the Cossacks fell through, and the Polish–Lithuanian military began gathering near the borders with Ukraine. A major camp was in

In the first half of 1649, the negotiations with the Cossacks fell through, and the Polish–Lithuanian military began gathering near the borders with Ukraine. A major camp was in Zbarazh

Zbarazh ( uk, Збараж, pl, Zbaraż, yi, זבאריזש, Zbarizh) is a city in Ternopil Raion of Ternopil Oblast (province) of western Ukraine. It is located in the historic region of Galicia. Zbarazh hosts the administration of Zbarazh u ...

, where Wiśniowiecki would arrive as well in late June, after gathering a new army of 3,000 in Wiśnicz, which was all he was able to afford at that time, due to most of his estates being overrun by the Cossacks. Wiśniowiecki's arrival raised the morale of the royal army, and despite having no official rank, both the common soldiers and the new regimentarz promised to take his advice, and even offered him the official command (which he refused). During the siege of Zbarazh, Wiśniowiecki was thus not the official commander (role was taken by regimentarz Andrzej Firlej

Andrzej is the Polish form of the given name Andrew.

Notable individuals with the given name Andrzej

* Andrzej Bartkowiak (born 1950), Polish film director and cinematographer

* Andrzej Bobola, S.J. (1591–1657), Polish saint, missionary and ma ...

) but most historians agree he was the real, if unofficial, commander of the Polish–Lithuanian army. The siege would last until the ceasefire of the Treaty of Zboriv

The Treaty of Zboriv was signed on August 18, 1649, after the Battle of Zboriv when the Crown forces of about 25,000, led by King John II Casimir of Poland, clashed against a combined force of Cossacks and Crimean Tatars, led by Hetman Bohdan Khm ...

. Wiśniowiecki's command during the siege was seen as phenomenal, and his popularity among the troops and nobility rose again, however the King, still not fond of him, gave him a relatively small reward (the land grant of ''starostwo przasnyskie'', much less when compared to several others he distributed around that time). Needing Wiśniowiecki's support in December that year, the King granted him once again a temporary hetman nomination, and several more land grants. In April 1650, Wiśniowiecki had to return his temporary hetman office to Mikołaj Potocki, recently released from Cossack's captivity. During December that year, in light of the growing tensions with Muscovy Muscovy is an alternative name for the Grand Duchy of Moscow (1263–1547) and the Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721). It may also refer to:

*Muscovy Company, an English trading company chartered in 1555

*Muscovy duck (''Cairina moschata'') and Domest ...

, Wiśniowiecki's military faction succeeded in convincing the Sejm to pass a resolution increasing the size of the army to 51,000, the largest army since the Cossack unrest began two years earlier.

The truce of Zboriv did not last long, and in the spring of 1651 Khmelnytsky's Cossacks began advancing west again. On 1 June 1651 Wiśniowiecki brought his private army to face the Cossacks in Sokal

Sokal ( uk, Сокаль, romanized: ''Sokal'') is a city located on the Bug River in Chervonohrad Raion, Lviv Oblast of western Ukraine. It hosts the administration of Sokal urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. The population is appr ...

. He commanded the left wing of the Polish–Lithuanian army in the victorious Battle of Berestechko

The Battle of Berestechko ( pl, Bitwa pod Beresteczkiem; uk, Берестецька битва, Битва під Берестечком) was fought between the Ukrainian Cossacks, led by Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, aided by their Crimean T ...

on 28–30 June . The Polish–Lithuanian army advanced after the retreating Cossacks, but on 17 July the King "left the whole army to Potocki ... and having given the order that the army march into Ukraine, the King himself parted ... to Warsaw to celebrate his victories over the Cossacks."Hrushevsky, p. 361 Later that year, on 14 August, Wiśniowiecki suddenly fell ill while in a camp near the village of Pawołocz, and died on 20 August 1651, at the age of only 39. His cause of death was never known, while some (even contemporaries) speculated he was poisoned, but no conclusive evidence to support such a claim have ever been found. Based on sparse descriptions of his illness and subsequent investigations, some medical historians suggest the cause of death might have been a disease related to cholera. However, one account states, "following a cheerful conversation with other officers who had congregated for a military council in his tent on Sunday 13 August N.S. he had eaten some cucumbers with zest and washed them down with mead, and from that contracted dysentery. After lying ill for a week, he died there, at Pavoloch".Hrushevsky, p. 366 He was given a "ceremonial funeral with the entire army present. On 22 August Wiśniowiecki's body was seen off with the utmost pomp on its journey to his residence".

Wiśniowiecki's indebted family was not able to provide him with a funeral his rank and fame deserved. In the end, he never received the large funeral and the temporary location of his body, the monastery of the Holy Cross at Łysa Góra

Łysa Góra (''Bald Mountain''; also known as Łysiec or Święty Krzyż) is a well-known hill in Świętokrzyskie Mountains, Poland. With a height of 595 metres (1,952 ft), it is the second highest point in that range (after Łysica at 61 ...

, became his final resting place. His body was believed lost in a fire at the end of the 18th century, which would prevent a modern reexamination of the cause of his death, although a body purported to be his has been discovered and is now on display in the monastery.

Wealth

The majority of the Wiśniowiecki family estates were found on the eastern side of theDnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine ...

River (Volhynian

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

, Ruthenian and Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

Voivodship

A voivodeship is the area administered by a voivode (Governor) in several countries of central and eastern Europe. Voivodeships have existed since medieval times and the area of extent of voivodeship resembles that of a duchy in western medieva ...

s), and most of them were acquired by Jeremi's grandfather, Aleksander Wiśniowiecki, in the 16th century. The capital of his estate was located at a fortified manor at Lubny

Lubny ( uk, Лубни́, ), is a city in Poltava Oblast (province) of central Ukraine. Serving as the administrative center of Lubny Raion (district), the city itself is administratively incorporated as a city of oblast significance and does no ...

, where his father rebuilt an old castle; the population of the town itself could be estimated at about 1,000. Wiśniowiecki inherited lands inhabited, according to an estimate from 1628, by about 4,500 people, of which Lubny was the largest town. Smaller towns in his lands included Khorol, Pyriatyn

Pyriatyn (, ) is a city in Poltava Oblast, Ukraine. It is the administrative center of Pyriatyn Raion. Population:

History

At the end of 1941 or beginning 1942, a ghetto guarded by policemen was established and numbered over 1,500 Jews by late ...

and Pryluky

Pryluky ( uk, Прилу́ки ) is a city and municipality located on the Udai River in Chernihiv Oblast, north-central Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Pryluky Raion (district). Located nearby is the Pryluky air base, a maj ...

. By 1646 his lands were inhabited by 230,000 people. The number of towns on his lands rose from several to about thirty, and their population increased as well. The prosperity of those lands reflected Wiśniowiecki's skills in economic management, and the income from his territories (estimated at about 600,000 zlotys yearly) made him one of the wealthiest magnates in the Commonwealth. Because of its size and relatively consistent borders, Wiśniowiecki's estate was often named ''Wiśniowieczczyzna'' ("Wiśniowieckiland").

Despite his wealth, he was not known for a lavish life. His court of about a hundred people was not known for being overly extravagant, he built no luxurious residences and did not even have a single portrait of himself made during his life. It is uncertain how Wiśniowiecki looked, although a number of portraits and other works depicting him exist. Jan Widacki

Jan Stefan Widacki (born 6 January 1948 in Kraków) is a Polish lawyer, historian, essayist, academic (professor since 1988), diplomat and politician.

Life

In 1969, Widacki graduated from law at the Jagiellonian University. He studied also philo ...

notes that much of the historiography concerning Wiśniowiecki focuses on the military and political aspects of his life, and few of his critics discuss his successes in the economic development of his estates.

Remembrance and popular culture

Wiśniowiecki was widely popular among the noble class, who saw in him a defender of tradition, a patriot and an able military commander. He was praised by many of his contemporaries, including a poet, Samuel Twardowski, as well as numerous diary writers and early historians. For his protection of civilian population, including Jews, during the Uprising, Wiśniowiecki has been commended by early Jewish historians. Until the 19th century, he has been idolized as the legendary, perfect "knight of the borderlands", his sculpture is among the twenty sculpture of famous historical personas in the 18th century "Knight Room" of the royalWarsaw Castle

The Royal Castle in Warsaw ( pl, Zamek Królewski w Warszawie) is a state museum and a national historical monument, which formerly served as the official royal residence of several Polish monarchs. The personal offices of the king and the admin ...

.

In the 19th century this image started to waver, as a new wave in historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians hav ...

began to reinterpret his life, and as the era of positivism in Poland put more value on builders, and less on warriors. Further, at that time the Polish historians began to question the traditional view of the "Ukrainian problem", and the way that the Polish noble class had dealt with the Cossacks. Slowly, Wiśniowiecki's image as a hero began to waver, with various aspects of his life and personality being questioned and criticized in the work of historians such as Karol Szajnocha

Karol Szajnocha (1818–1868) was a Polish writer, historian, and independence activist. Self-taught, he would nonetheless become a notable Polish historian of the partitions period.

Biography

Karol Szajnocha was born as on 20 November 1818 in K ...

and Józef Szujski.

While Wiśniowiecki's portrayal (as a major secondary character) in the first part of Henryk Sienkiewicz

Henryk Adam Aleksander Pius Sienkiewicz ( , ; 5 May 1846 – 15 November 1916), also known by the pseudonym Litwos (), was a Polish writer, novelist, journalist and Nobel Prize laureate. He is best remembered for his historical novels, espe ...

's trilogy

A trilogy is a set of three works of art that are connected and can be seen either as a single work or as three individual works. They are commonly found in literature, film, and video games, and are less common in other art forms. Three-part wo ...

, ''With Fire and Sword

''With Fire and Sword'' ( pl, Ogniem i mieczem, links=no) is a historical novel by the Polish author Henryk Sienkiewicz, published in 1884. It is the first volume of a series known to Poles as The Trilogy, followed by ''The Deluge'' (''Potop'', ...

'' which describes the history of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth during the Uprising, was rather positive, criticism of his persona intensified, in particular from Sienkiewicz detractors such as Zygmunt Kaczkowski

Zygmunt Kaczkowski (1825–1896) was a Polish writer, independence activist, and an Austrian spy. He was convicted in 1864 of espionage by an underground court in the January Uprising. There is a consensus that this accomplished writer is today a ...

and Olgierd Górka

Algirdas ( be, Альгерд, Alhierd, uk, Ольгерд, Ольґерд, Olherd, Olgerd, pl, Olgierd; – May 1377) was the Grand Duke of Lithuania. He ruled the Lithuanians and Ruthenians from 1345 to 1377. With the help of his brot ...

. The 1930s saw a first modern historical work about Wiśniowiecki, by . In the era of the People's Republic of Poland

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million nea ...

, the Communist Party's ideology dictated that all historians present him as an "enemy of the people", although this began to be relaxed after 1965. Widacki, analyzing the work of other historians notes that Władysław Czapliński

Władysław Czapliński (3 October 1905 in Tuchów – 17 August 1981 in Wrocław) was a Polish historian, a professor of the University of Wrocław, author of many popular books about Polish history.

He finished his studies at the Jagiellonian Un ...

was rather sympathetic to Wiśniowiecki, while Paweł Jasienica

Paweł Jasienica was the pen name of Leon Lech Beynar (10 November 1909 – 19 August 1970), a Polish historian, journalist, essayist and soldier.

During World War II, Jasienica (then, Leon Beynar) fought in the Polish Army, and later, the ...

was critical of him. Andrzej Seweryn

Andrzej Teodor Seweryn (born 25 April 1946) is a Polish actor and director. One of the most successful Polish theatre actors, he starred in over 50 films, mostly in Poland, France and Germany. He is also one of only three non-French actors to ...

played Jeremi Wiśniowiecki in the 1999 film ''With Fire and Sword

''With Fire and Sword'' ( pl, Ogniem i mieczem, links=no) is a historical novel by the Polish author Henryk Sienkiewicz, published in 1884. It is the first volume of a series known to Poles as The Trilogy, followed by ''The Deluge'' (''Potop'', ...

''.

Wiśniowiecki was the main subject of one of Jacek Kaczmarski

Jacek Marcin Kaczmarski (22 March 1957 – 10 April 2004) was a Polish singer, songwriter, poet and author.

Life

He was the son of painter Anna Trojanowska-Kaczmarska, a Pole of Jewish background, and the artist Janusz Kaczmarski.

Kaczmarski ...

's 1993 songs ''Kniazia Jaremy nawrócenie'' (''The Conversion of Knyaz Jarema'').

See also

*Lithuanian nobility

The Lithuanian nobility or szlachta (Lithuanian: ''bajorija, šlėkta'') was historically a legally privileged hereditary elite class in the Kingdom of Lithuania and Grand Duchy of Lithuania (including during period of foreign rule 1795–191 ...

* Wiśniowiecki family

* List of szlachta

References

Sources

* * * *External links

Page dedicated to Jeremi Wisniowiecki, in Polish

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jeremi Wisniowiecki Wisniowiecki, Jeremi Wisniowiecki, Jeremi Military personnel of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Wisniowiecki, Jeremi Wiśniowiecki family Wisniowiecki, Jeremi Polish Roman Catholics Former Polish Orthodox Christians Polish people of Romanian descent 17th-century Polish people Polish people of the Smolensk War Polish military personnel of the Khmelnytsky Uprising Voivodes of the Ruthenian Voivodeship People from Kiev Voivodeship People from Lubny