jedediah smith on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jedediah Strong Smith (January 6, 1799 – May 27, 1831) was an American clerk, transcontinental pioneer, frontiersman, hunter, trapper, author,

Smith was born in Jericho, now Bainbridge,

Smith was born in Jericho, now Bainbridge,

Coming from a family of modest means, Smith sought to make his own way. He may have left his family in search of a trade or employment a year prior to their settlement in Green Township. In 1822, Smith was living in St. Louis. The same year Smith responded to an advertisement in the Missouri Gazette placed by General William H. Ashley. General Ashley and Major Andrew Henry, veterans of the

Coming from a family of modest means, Smith sought to make his own way. He may have left his family in search of a trade or employment a year prior to their settlement in Green Township. In 1822, Smith was living in St. Louis. The same year Smith responded to an advertisement in the Missouri Gazette placed by General William H. Ashley. General Ashley and Major Andrew Henry, veterans of the

In the spring of 1823, Major Henry ordered Smith back down Missouri River to the Grand River with a message for Ashley to buy horses from the Arikaras, who because of a recent skirmish with

In the spring of 1823, Major Henry ordered Smith back down Missouri River to the Grand River with a message for Ashley to buy horses from the Arikaras, who because of a recent skirmish with

After the campaign, in the fall of 1823, Smith and several other of Ashley's men traveled downriver to

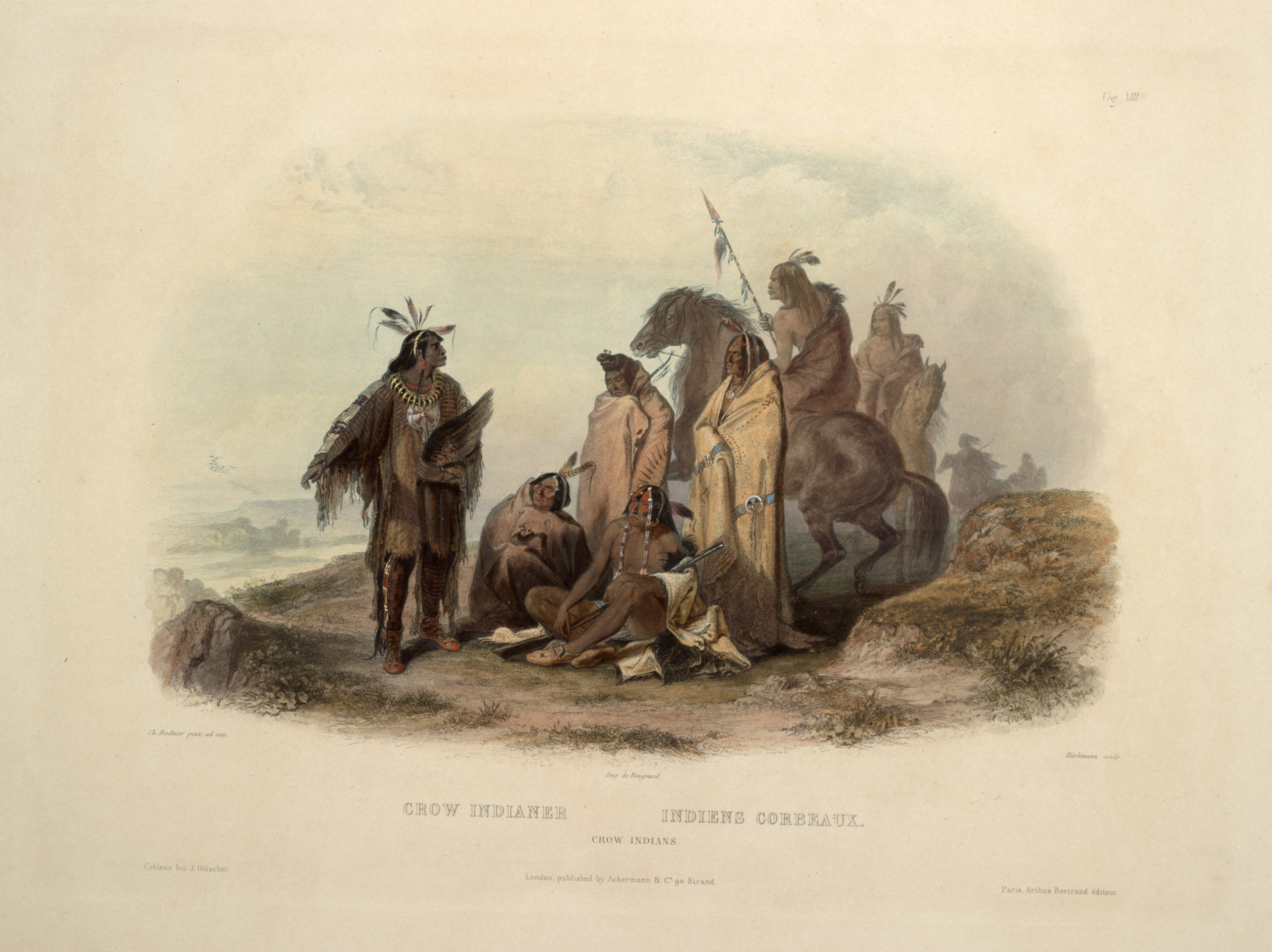

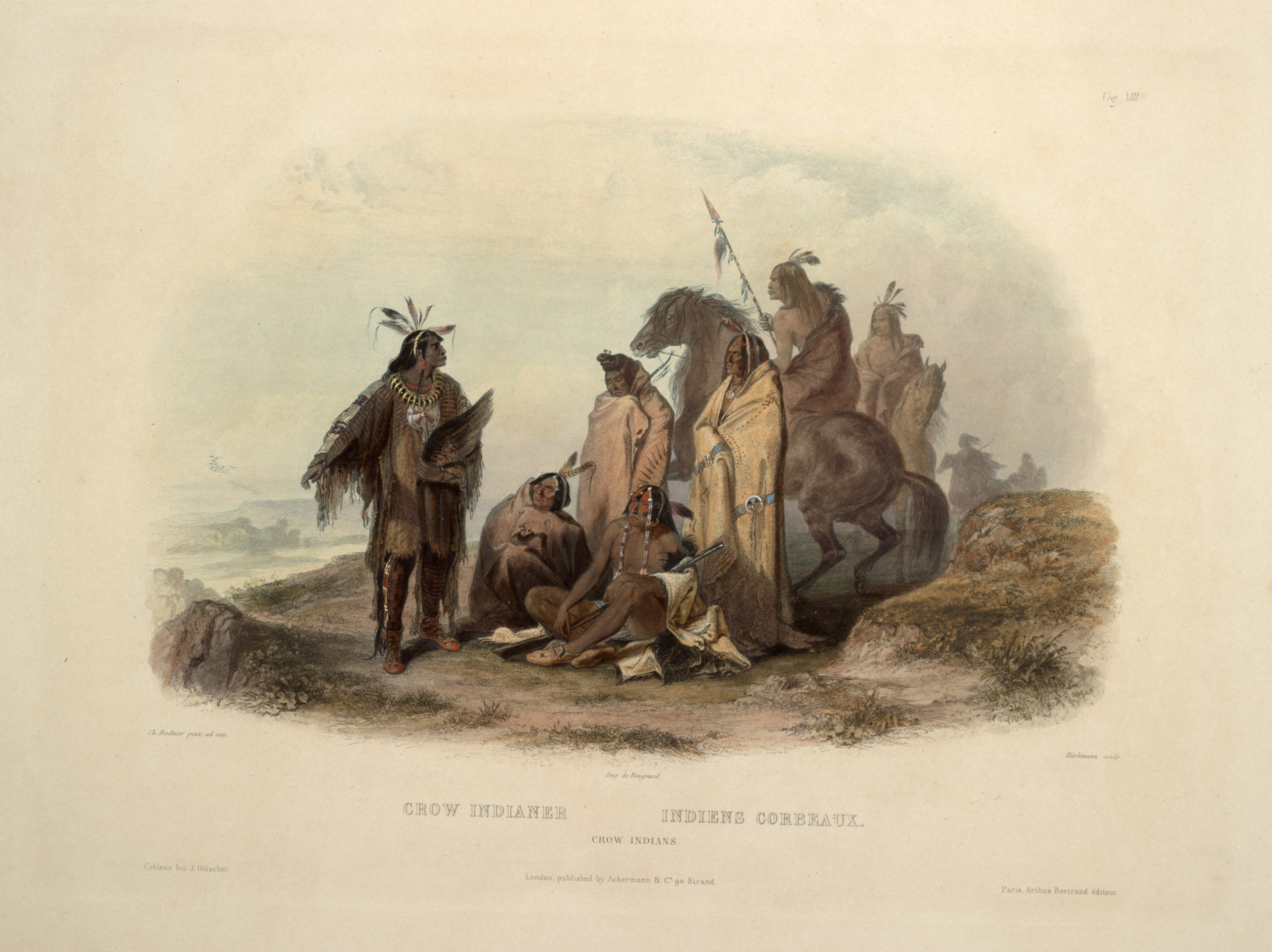

After the campaign, in the fall of 1823, Smith and several other of Ashley's men traveled downriver to  The party spent the rest of 1823 wintering in the Wind River Valley. In 1824, Smith sent an expedition to find an expedient route through the Rocky Mountains. Smith was able to retrieve information from Crow natives. When communicating with the Crows, one of Smith's men made a unique map (consisting of buffalo hide and sand), and the Crows were able to show Smith and his men the direction to the South Pass. Smith and his men crossed through this pass from east to west and encountered the

The party spent the rest of 1823 wintering in the Wind River Valley. In 1824, Smith sent an expedition to find an expedient route through the Rocky Mountains. Smith was able to retrieve information from Crow natives. When communicating with the Crows, one of Smith's men made a unique map (consisting of buffalo hide and sand), and the Crows were able to show Smith and his men the direction to the South Pass. Smith and his men crossed through this pass from east to west and encountered the

The next day, the rest of Smith's men arrived at the mission, and that night the head of the garrison at the mission confiscated all their guns. On December 8, Smith was summoned to

The next day, the rest of Smith's men arrived at the mission, and that night the head of the garrison at the mission confiscated all their guns. On December 8, Smith was summoned to  After a difficult crossing of the Sierra Nevada near

After a difficult crossing of the Sierra Nevada near

As agreed, Ashley had sent provisions for the rendezvous, and his men took back of Smith, Jackson & Sublette furs and a letter from Smith to William Clark, then in the office of the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the region west of the

As agreed, Ashley had sent provisions for the rendezvous, and his men took back of Smith, Jackson & Sublette furs and a letter from Smith to William Clark, then in the office of the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the region west of the  Smith and the other survivors were again well received in San Gabriel. The party moved north to meet with the group that had been left in the

Smith and the other survivors were again well received in San Gabriel. The party moved north to meet with the group that had been left in the

When Smith's party left Mexican Alta California and entered the Oregon Country, the

When Smith's party left Mexican Alta California and entered the Oregon Country, the

In 1829, Captain Smith personally organized a fur trade expedition into the

In 1829, Captain Smith personally organized a fur trade expedition into the

After Smith's return to St. Louis in 1830, he and his partners wrote a letter on October 29 to Secretary of War Eaton, who at the time was involved in a notorious Washington cabinet scandal known as the

After Smith's return to St. Louis in 1830, he and his partners wrote a letter on October 29 to Secretary of War Eaton, who at the time was involved in a notorious Washington cabinet scandal known as the

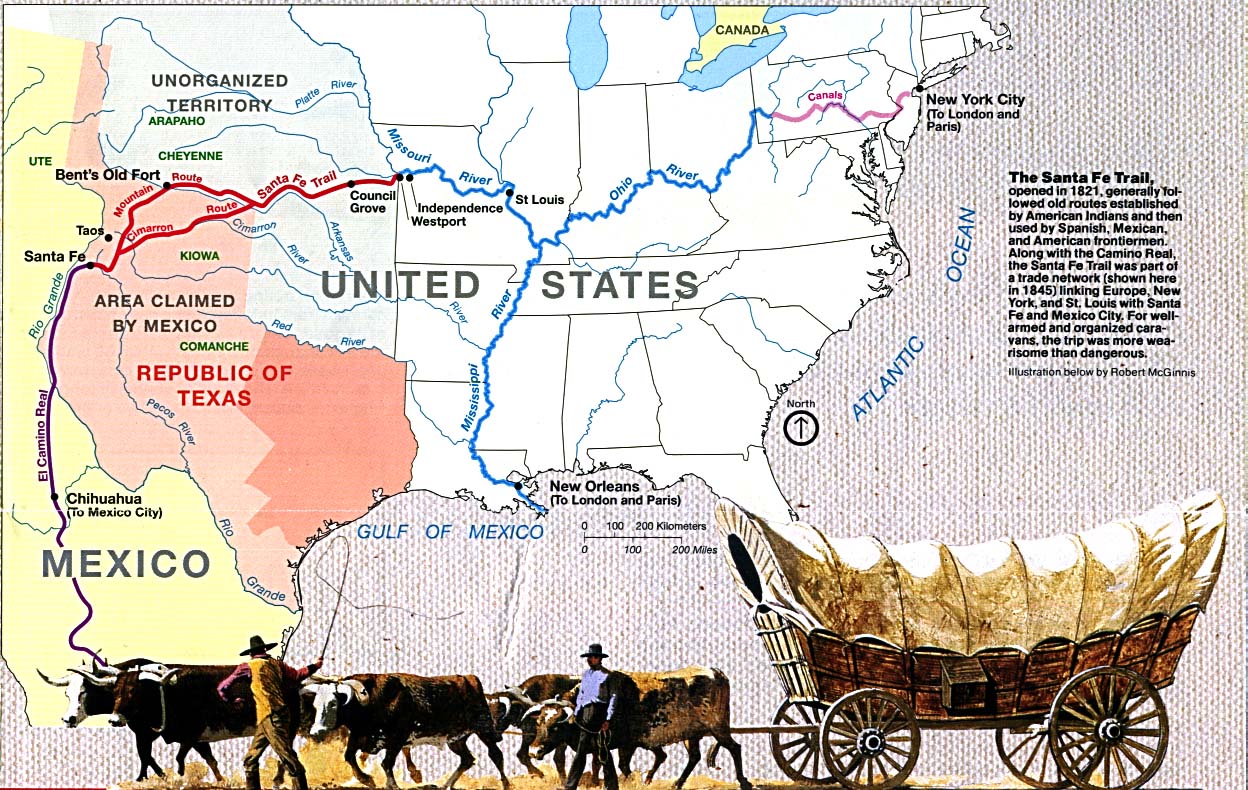

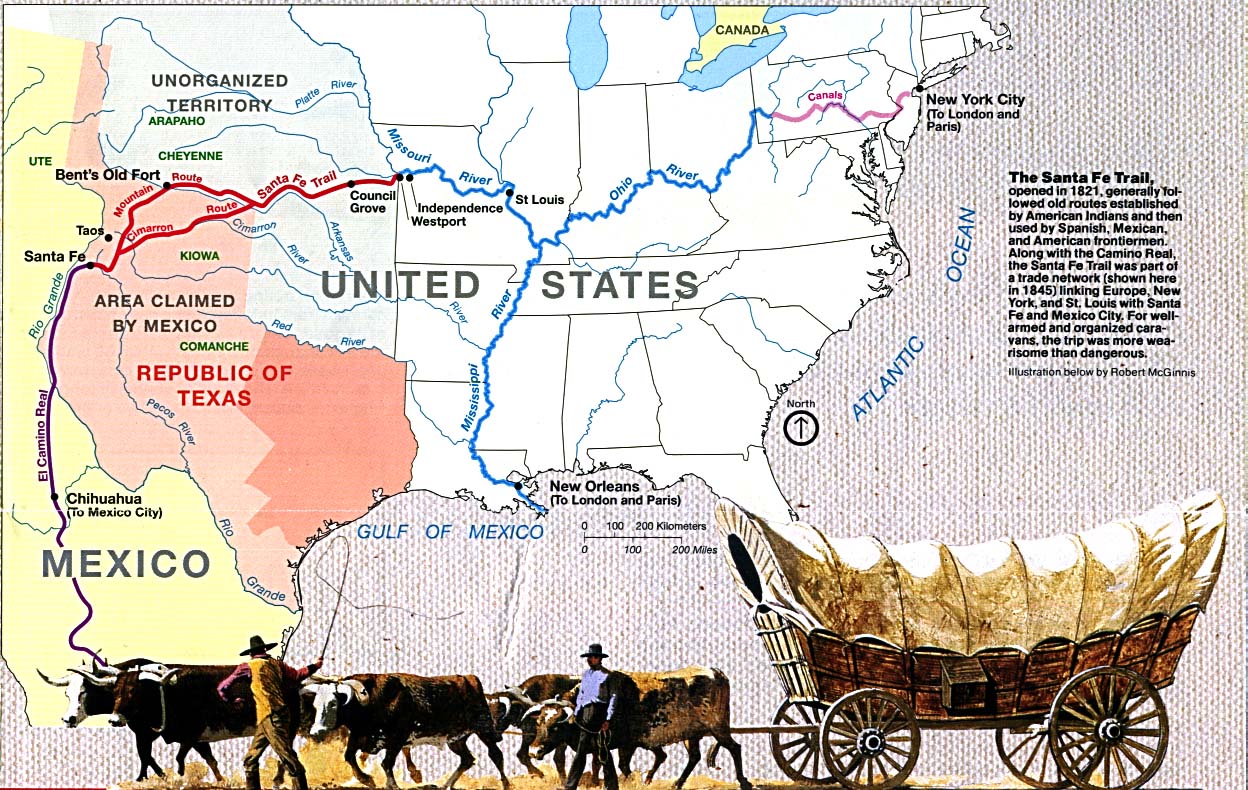

Having no response from Eaton, Smith joined his partners and left St. Louis to trade in Santa Fe on April 10, 1831. Smith was leading the caravan on the

Having no response from Eaton, Smith joined his partners and left St. Louis to trade in Santa Fe on April 10, 1831. Smith was leading the caravan on the

''The Ashley-Smith Explorations and the Discovery of a Central Route to the Pacific, 1822–1829: With the Original Journals''

published in 1918. During the 1920s, Maurice S. Sullivan traced descendants of Smith's siblings and found two portions of the narrative of Smith's travels, written in the hand of Samuel Parkman who had been hired to assist in compiling the document after Smith's return to St. Louis in 1830. The narrative's impending publication had been announced in a St. Louis newspaper as late as 1840, but never happened. In 1934, Sullivan published the remnants, documenting Smith's travels in 1821 and 1822 and from June 1827 until the Umpqua massacre a year later, in ''The Travels of Jedediah Smith'', giving a new documented perspective of Smith's explorations. Along with the narrative, Sullivan published the portion of Alexander McLeod's journal documenting the search for any surviving members of Smith's party and the recovery of his property after the Umpquah massacre. The ''Dictionary of American Biography'', Volume 17, edited by Dumas Malone, published in 1935, contains an article on Smith authored by Joseph Schafer. The next year, the first comprehensive biography of Smith: ''Jedediah Smith: Trader and Trail Breaker'' by Sullivan was posthumously published, but it was Dale Morgan's book, ''Jedediah Smith and the Opening of the West'', published in 1953, that established Smith as an authentic American hero whose explorations were overshadowed by the Lewis and Clark Expedition. According to Maurice S. Sullivan, Smith was "the first white man to cross the future state of Nevada, the first to conquer the High Sierra of California, and the first to explore the entire Pacific Slope from Lower California to the banks of the Columbia River". He was known for his many systematic recorded observations on nature and topography. His expeditions also raised doubts about the existence of the legendary Buenaventura River. Jedediah Smith's explorations were the main basis for accurate Pacific West maps. He and his partners, Jackson and Sublette, produced a map that, in a eulogy for Smith printed in the ''Illinois Monthly Magazine'' for June 1832, the unknown author claimed: "This map is now probably the best extant, of the Rocky Mountains, and the country on both sides, from the States to the Pacific." This map has been called "a landmark in mapping of the American West" originally published in The original map is lost, its content was overlaid and annotated by George Gibbs on an 1845 base map by John C. Frémont, which is on file at th

According to Maurice S. Sullivan, Smith was "the first white man to cross the future state of Nevada, the first to conquer the High Sierra of California, and the first to explore the entire Pacific Slope from Lower California to the banks of the Columbia River". He was known for his many systematic recorded observations on nature and topography. His expeditions also raised doubts about the existence of the legendary Buenaventura River. Jedediah Smith's explorations were the main basis for accurate Pacific West maps. He and his partners, Jackson and Sublette, produced a map that, in a eulogy for Smith printed in the ''Illinois Monthly Magazine'' for June 1832, the unknown author claimed: "This map is now probably the best extant, of the Rocky Mountains, and the country on both sides, from the States to the Pacific." This map has been called "a landmark in mapping of the American West" originally published in The original map is lost, its content was overlaid and annotated by George Gibbs on an 1845 base map by John C. Frémont, which is on file at th

American Geographical Society Library

at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

here

*

Jedediah Smith - Frontier Legend

Jedediah Smith Trail studySmith/Bacon Family Collection

available at th

Jedediah Smith Society Collection

available at th

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smith, Jedediah 1799 births 1831 deaths American explorers American fur traders American hunters American people of English descent Bear attack victims Deaths by stabbing in the United States Explorers of California Explorers of North America Explorers of Oregon Mohave Trail Mountain men Oregon Trail People from Bainbridge, New York Santa Fe Trail

cartographer

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an im ...

, mountain man and explorer of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

, the Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

, and the Southwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

during the early 19th century. After 75 years of obscurity following his death, Smith was rediscovered as the American whose explorations led to the use of the -wide South Pass as the dominant point of crossing the Continental Divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not ...

for pioneers on the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and Westward Expansion Trails, emigrant trail in the United States that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of what ...

.

Coming from modest family background, Smith traveled to St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

and joined William H. Ashley and Andrew Henry's fur trading company in 1822. Smith led the first documented exploration from the Salt Lake

A salt lake or saline lake is a landlocked body of water that has a concentration of salts (typically sodium chloride) and other dissolved minerals significantly higher than most lakes (often defined as at least three grams of salt per litre). ...

frontier to the Colorado River

The Colorado River ( es, Río Colorado) is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and northern Mexico. The river drains an expansive, arid drainage basin, watershed that encompasses parts of ...

. From there, Smith's party became the first United States citizens to cross the Mojave Desert

The Mojave Desert ( ; mov, Hayikwiir Mat'aar; es, Desierto de Mojave) is a desert in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada mountains in the Southwestern United States. It is named for the indigenous Mojave people. It is located primarily in ...

into what is now the state of California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

but which at that time was part of Mexico. On the return journey, Smith and his companions were likewise the first U.S. citizens to explore and cross the Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primarily ...

and the treacherous Great Basin Desert

The Great Basin Desert is part of the Great Basin between the Sierra Nevada (U.S.), Sierra Nevada and the Wasatch Range. The desert is a geographical region that largely overlaps the Great Basin shrub steppe defined by the World Wildlife Fund, a ...

. The following year, Smith and companions were the first U.S. explorers to travel north from California overland to the Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been created by the Treaty of 1818, co ...

. Surviving three Native American massacres and one bear mauling, Smith's explorations and documented travels were important resources to later American westward expansion

The United States of America was created on July 4, 1776, with the U.S. Declaration of Independence of thirteen British colonies in North America. In the Lee Resolution two days prior, the colonies resolved that they were free and independe ...

.

In March 1831, while in St. Louis, Smith requested of Secretary of War John H. Eaton

John Henry Eaton (June 18, 1790November 17, 1856) was an American politician and diplomat from Tennessee who served as U.S. Senator and as Secretary of War in the administration of Andrew Jackson. He was 28 years, 4 months, and 29 days old when ...

a federally-funded exploration of the West, but to no avail. Smith informed Eaton that he was completing a map of the West derived from his own journeys. In May, Smith and his partners launched a planned paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

trading party to Santa Fe. On May 27, while searching for water in present-day southwest Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

, Smith disappeared. It was learned weeks later that he had been killed during an encounter with the Comanche

The Comanche or Nʉmʉnʉʉ ( com, Nʉmʉnʉʉ, "the people") are a Native American tribe from the Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the federally recognized Comanche Nation, headquartered in La ...

– his body was never recovered.

After his death, Smith and his accomplishments were mostly forgotten by Americans. At the beginning of the 20th century, scholars and historians made efforts to recognize and study his achievements. In 1918, a book by Harrison Clifford Dale was published covering Ashley-Smith's western explorations. In 1935, Smith's summary autobiography was finally listed in a biographical dictionary. Smith's first comprehensive biography by Maurice S. Sullivan was published in 1936. A popular Smith biography by Dale Morgan

Lowell Dale Morgan (December 18, 1914 – March 30, 1971), generally cited as Dale Morgan or Dale L. Morgan, was an American historian, accomplished researcher, biographer, editor, and critic. He specialized in material on Utah history, Mormon ...

, published in 1953, established Smith as an authentic national hero. Smith's map of the West in 1831 was used by the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

, including western explorer John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

, during the early 1840s.

Early life

Smith was born in Jericho, now Bainbridge,

Smith was born in Jericho, now Bainbridge, Chenango County

Chenango County is a county located in the south-central section U.S. state of New York. As of the 2020 census, the population was 47,220. Its county seat is Norwich. The county's name originates from an Oneida word meaning 'large bull-thist ...

, New York, on January 6, 1799, to Jedediah Smith I, a general store owner from New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, and Sally Strong, both of whom were descended entirely from families that came to New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

from England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

during the Puritan emigration between 1620 and 1640.

Smith received adequate English instruction, learned some Latin, and was taught how to write decently. Around 1810, Smith's father was caught up in a legal issue involving counterfeit currency

Counterfeit money is currency produced without the legal sanction of a state or government, usually in a deliberate attempt to imitate that currency and so as to deceive its recipient. Producing or using counterfeit money is a form of fraud or ...

after which the elder Smith moved his family west to Erie County, Pennsylvania

Erie County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is the northernmost county in Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, the population was 270,876. Its county seat is Erie. The county was created in 1800 and later organized in 1803.

...

.

At age 13, Smith worked as a clerk on a Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also has t ...

freighter, where he learned business practices and probably met traders returning from the far west to Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

. This work gave Smith an ambition for adventurous wilderness trade. According to Dale L. Morgan, Smith's love of nature and adventure came from his mentor, Dr. Titus G. V. Simons, a pioneer medical doctor who was on close terms with the Smith family. Morgan speculated that Simons gave the young Smith a copy of Meriwether Lewis

Meriwether Lewis (August 18, 1774 – October 11, 1809) was an American explorer, soldier, politician, and public administrator, best known for his role as the leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, with ...

' and William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Misso ...

's 1814 book of their 1804–1806 expedition to the Pacific, and according to legend Smith carried this journal on all of his travels throughout the American West. Smith provided Clark, who had become superintendent of Indian affairs, much information from his own expeditions to the West. In 1817, the Smith family moved westward to Ohio and settled in Green Township in what is present-day Ashland County.

Smith joins "Ashley's Hundred"

Coming from a family of modest means, Smith sought to make his own way. He may have left his family in search of a trade or employment a year prior to their settlement in Green Township. In 1822, Smith was living in St. Louis. The same year Smith responded to an advertisement in the Missouri Gazette placed by General William H. Ashley. General Ashley and Major Andrew Henry, veterans of the

Coming from a family of modest means, Smith sought to make his own way. He may have left his family in search of a trade or employment a year prior to their settlement in Green Township. In 1822, Smith was living in St. Louis. The same year Smith responded to an advertisement in the Missouri Gazette placed by General William H. Ashley. General Ashley and Major Andrew Henry, veterans of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, had established a partnership to engage in the fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

and were looking for "One Hundred" "''Enterprising Young Men''" to explore and trap in the Rocky Mountains. Superintendent of Indian Affairs William Clark had granted Ashley and Henry license to trade with Native Americans in the upper Missouri River, and he actively encouraged them to compete with the powerful British fur trade in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

. Smith, a 6-foot-tall, 23-year-old with a commanding presence, impressed General Ashley to hire him. In late spring, Smith started up the Missouri on the keelboat

A keelboat is a riverine cargo-capable working boat, or a small- to mid-sized recreational sailing yacht. The boats in the first category have shallow structural keels, and are nearly flat-bottomed and often used leeboards if forced in open wat ...

''Enterprize'', which sank three weeks into the journey. Smith and the other men waited at the site of the wreck for a replacement boat, hunting and foraging for food. Ashley brought up another boat with an additional 46 men and upon proceeding upriver, Smith got his first glimpse of the western frontier, coming into contact with the Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

and Arikara

Arikara (), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

. On October 1, Smith reached Fort Henry at the mouth of the ''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

Yellowstone River

The Yellowstone River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately long, in the Western United States. Considered the principal tributary of upper Missouri, via its own tributaries it drains an area with headwaters across the mountains an ...

, which had just been built by Major Henry and the men that he had led up earlier. Smith and some other men continued up Missouri River to the mouth of the Musselshell River

The Musselshell River is a tributary of the Missouri River, long from its origins at the confluence of its North and South Forks near Martinsdale, Montana to its mouth on the Missouri River. It is located east of the Continental divide entir ...

, where they built a camp from which to trap through the winter.

Arikaras attack

In the spring of 1823, Major Henry ordered Smith back down Missouri River to the Grand River with a message for Ashley to buy horses from the Arikaras, who because of a recent skirmish with

In the spring of 1823, Major Henry ordered Smith back down Missouri River to the Grand River with a message for Ashley to buy horses from the Arikaras, who because of a recent skirmish with Missouri Fur Company

The Missouri Fur Company (also known as the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company or the Manuel Lisa Trading Company) was one of the earliest fur trading companies in St. Louis, Missouri. Dissolved and reorganized several times, it operated under various ...

men were antagonistic to the white traders. Ashley, who was bringing supplies as well as 70 new men upriver by boat, met Smith at the Arikara village on May 30. They negotiated a trade for several horses and 200 buffalo robes and planned to leave as soon as possible to avert trouble, but weather delayed them. Before they could depart, an incident provoked an Arikara attack. Forty Ashley men, including Smith, were caught in a vulnerable position, and 12 were killed in the ensuing battle. Smith's conduct during the defense was the foundation of his reputation: "When his party was in danger, Mr. Smith was always among the foremost to meet it, and the last to fly; those who saw him on shore, at the Riccaree fight, in 1823, can attest to the truth of this assertion."

Smith and another man were selected by Ashley to return to Fort Henry on foot to inform Henry of the defeat. Ashley and the rest of the surviving party rode back down the river, ultimately enlisting aid from Colonel Henry Leavenworth who was the commander of Fort Atkinson. In August, Leavenworth sent 250 military men along with 80 Ashley-Henry men, 60 men of the Missouri Fur Company and a number of Lakota Sioux warriors to subdue the Arikaras. After a botched campaign, a peace treaty was negotiated. Smith had been appointed commander of one of the two squads of the Ashley-Henry men and was thereafter known as "Captain Smith".

First expedition, grizzly bear attack, and South Pass

After the campaign, in the fall of 1823, Smith and several other of Ashley's men traveled downriver to

After the campaign, in the fall of 1823, Smith and several other of Ashley's men traveled downriver to Fort Kiowa

Fort Kiowa, officially Fort Lookout and also called Fort Brazeau/Brasseaux,Lotte Govaerts, "Real Stories behind The Revenant, Part III: Fort Kiowa", Rogers Archaeology Lab/ref> was a 19th-century fur trading post located on the Missouri River bet ...

. Leaving Fort Kiowa in September, Smith and 10 to 16 men headed west, beginning his first far-western expedition, to make their way overland to the Rocky Mountains. Smith and his party were the first Euro-Americans to explore the southern Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black Elk P ...

, in present-day South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota people, Lakota and Dakota peo ...

and eastern Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

. While looking for the Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus '' Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

tribe to obtain fresh horses and get westward directions, Smith was attacked by a large grizzly bear

The grizzly bear (''Ursus arctos horribilis''), also known as the North American brown bear or simply grizzly, is a population or subspecies of the brown bear inhabiting North America.

In addition to the mainland grizzly (''Ursus arctos horri ...

. Smith was tackled to the ground by the grizzly, breaking his ribs. Members of his party witnessed him fight the bear, which ripped open his side with its claws and took his head in its mouth. When the bear retreated, Smith's men ran to help him. They found his scalp and ear ripped off, but he convinced a friend, Jim Clyman, to sew it loosely back on, giving him directions. The trappers fetched water, bound up his broken ribs, and cleaned his wounds. After recuperating from his injuries, Smith wore his hair long to cover the large scar from his eyebrow to his ear. The only known portrait of Jedediah Smith, painted after his death in 1831, showed the long hair he wore over the side of his head to hide his scars.

The party spent the rest of 1823 wintering in the Wind River Valley. In 1824, Smith sent an expedition to find an expedient route through the Rocky Mountains. Smith was able to retrieve information from Crow natives. When communicating with the Crows, one of Smith's men made a unique map (consisting of buffalo hide and sand), and the Crows were able to show Smith and his men the direction to the South Pass. Smith and his men crossed through this pass from east to west and encountered the

The party spent the rest of 1823 wintering in the Wind River Valley. In 1824, Smith sent an expedition to find an expedient route through the Rocky Mountains. Smith was able to retrieve information from Crow natives. When communicating with the Crows, one of Smith's men made a unique map (consisting of buffalo hide and sand), and the Crows were able to show Smith and his men the direction to the South Pass. Smith and his men crossed through this pass from east to west and encountered the Green River Green River may refer to:

Rivers

Canada

* Green River (British Columbia), a tributary of the Lillooet River

*Green River, a tributary of the Saint John River, also known by its French name of Rivière Verte

*Green River (Ontario), a tributary of ...

near the mouth of the Big Sandy River in what is now Wyoming. The group broke into two parties—one led by Smith and the other by Thomas Fitzpatrick—to trap upstream and downstream on the Green. The two groups met in July on the Sweetwater River, and it was decided that Fitzpatrick and two others would take the furs and the news of the identification of a feasible highway route through the Rockies to Ashley in St. Louis. Scottish-Canadian trapper Robert Stuart, employed by John Jacob Astor

John Jacob Astor (born Johann Jakob Astor; July 17, 1763 – March 29, 1848) was a German-American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor who made his fortune mainly in a fur trade monopoly, by smuggling opium into China, and ...

's Pacific Fur Company

The Pacific Fur Company (PFC) was an American fur trade venture wholly owned and funded by John Jacob Astor that functioned from 1810 to 1813. It was based in the Pacific Northwest, an area contested over the decades between the United Kingdom o ...

, had previously discovered the South Pass, in mid-October 1812, while traveling overland to St. Louis from Fort Astoria

Fort Astoria (also named Fort George) was the primary fur trading post of John Jacob Astor's Pacific Fur Company (PFC). A maritime contingent of PFC staff was sent on board the ''Tonquin (1807 ship), Tonquin'', while another party traveled overl ...

, but this information was kept secret. Smith later wrote a letter to Secretary of War John Eaton in 1830 making the location of the South Pass public information.

Major Henry returned to St. Louis on August 30, and Ashley began making plans to lead a caravan back to the Rockies to regroup with his men. Henry declined to return with Ashley, instead choosing to retire from the fur trade.

After Fitzpatrick left, Smith and six others, including William Sublette

William Lewis Sublette, also spelled Sublett (September 21, 1798 – July 23, 1845), was an American frontiersman, trapper, fur trader, explorer, and mountain man. After 1823, he became an agent of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, along with his ...

, again crossed South Pass, and in September 1824 encountered a group of Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

freemen trappers who had split off from the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business div ...

Snake Country brigade led by Alexander Ross. Smith told the Iroquois they could get better prices for their furs by selling to American traders and accompanied the brigade back to its base at Flathead Post Saleesh House, also known as Flathead Post, was a North West Company fur trading post built near present-day Thompson Falls, Montana in 1809 by David Thompson and James McMillan of the North West Company. It became a Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) p ...

in Montana. Smith then accompanied the brigade led by Peter Skene Ogden back southeast, leaving Flathead Post in December 1824. In April 1825, on the Bear River in what is now Utah, Smith and his companions split from the brigade and joined a group of Americans that had wintered in the area. In late May 1825, on the Weber River

The Weber River ( ) is a long river of northern Utah, United States. It begins in the northwest of the Uinta Mountains and empties into the Great Salt Lake. The Weber River was named for American fur trapper John Henry Weber.

The Weber River ...

near present Mountain Green, Utah

Mountain Green is a census-designated place in northwestern Morgan County, Utah, United States. The population was 2,309 at the 2010 census. Located up the Weber River from Ogden, Mountain Green is the world headquarters of the Browning Arms ...

, 23 freemen trappers deserted from Ogden's brigade, backed up by a group of American trappers led by Johnson Gardner. Several of the deserters were among the Iroquois trappers Smith had assisted in September 1824. Smith may have been present at the confrontation, but the extent of his involvement in the desertion of the freemen, if any, is unclear.

First Rendezvous of 1825

Ashley left St. Louis late in 1824 and after an exploring expedition in Wyoming and Utah, he and Smith were reunited on July 1, 1825, at what would become the first rendezvous. During the rendezvous, Ashley offered Smith a partnership to replace Henry. Smith returned to St. Louis for a time, where he asked Robert Campbell to join the company as a clerk.Second Rendezvous of 1826

During the second rendezvous in the summer of 1826, Ashley decided no longer to be directly involved in the business of harvesting furs. Smith left a cache near the rendezvous site at what would become known as Cache Valley in northern Utah, and he and Ashley traveled north to meet David E. Jackson and Sublette at Bear River area near present-daySoda Springs, Idaho

Soda Springs is a city in Caribou County, Idaho, United States. Its population was 3,058 at the time of the 2010 census. The city has been the county seat of Caribou County since the county was organized in 1919. In the 1860s, Soda Springs serve ...

. Ashley sold his interest in his and Smith's partnership to the newly created partnership of Smith, Jackson & Sublette but agreed to continue to send supplies to the rendezvous

and broker the sale of furs brought to him in St. Louis.

The new partners were immediately faced with the reality that beaver

Beavers are large, semiaquatic rodents in the genus ''Castor'' native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. There are two extant species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers ar ...

were rapidly disappearing from the region where the two previous partnerships had traditionally trapped. Contemporaneous maps promised untrapped rivers to the west,

such as the non-existent Buenaventura. The legendary Buenaventura was thought to be a navigable waterway to the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

possibly providing an alternative to packing loads of furs back to St. Louis.Miles Harvey

Miles Harvey is an American journalist and author. He is best known for his 2000 book, ''The Island of Lost Maps'', which recounted the story of a Floridian named Gilbert Bland, who stole old and precious maps from libraries across America.

H ...

, ''The Island of Lost Maps: A True Story of Cartographic Crime'', p. 208–215. New York : Random House

Random House is an American book publisher and the largest general-interest paperback publisher in the world. The company has several independently managed subsidiaries around the world. It is part of Penguin Random House, which is owned by Germ ...

, 2000. (, ) The previous spring, Smith had searched for rivers flowing to the Pacific west and northwest of the Great Salt Lake

The Great Salt Lake is the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere and the eighth-largest terminal lake in the world. It lies in the northern part of the U.S. state of Utah and has a substantial impact upon the local climate, particula ...

. Although he pushed into eastern Nevada, he failed to find the Humboldt River

The Humboldt River is an extensive river drainage system located in north-central Nevada. It extends in a general east-to-west direction from its headwaters in the Jarbidge, Independence, and Ruby Mountains in Elko County, to its terminus in the ...

, the probable source of the legend of the Buenaventura. Having determined the Buenaventura must lie further south, Smith made plans for an exploratory expedition deep into the Mexican territory of Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

.

First trip to California, 1826–27

Smith and his party of 15 left the Bear River on August 7, 1826, and after retrieving the cache he had left earlier, they headed south through present-day Utah and Nevada to theColorado River

The Colorado River ( es, Río Colorado) is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and northern Mexico. The river drains an expansive, arid drainage basin, watershed that encompasses parts of ...

, finding increasingly harsh conditions and difficult travel. Finding shelter in a friendly Mojave village near present-day Needles, California

Needles is a city in San Bernardino County, California, in the Mojave Desert region of Southern California. Situated on the western banks of the Colorado River, Needles is located near the Californian border with Arizona and Nevada. The city is a ...

, the men and horses recuperated. Smith hired two refugees from the Spanish missions in California

The Spanish missions in California ( es, Misiones españolas en California) comprise a

series of 21 religious outposts or missions established between 1769 and 1833 in what is now the U.S. state of California. Founded by Catholic priests o ...

to guide them west. After leaving the river and heading into the Mojave Desert

The Mojave Desert ( ; mov, Hayikwiir Mat'aar; es, Desierto de Mojave) is a desert in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada mountains in the Southwestern United States. It is named for the indigenous Mojave people. It is located primarily in ...

, the guides led them through the desert via the Mohave Trail

The Mohave Trail was a Native American trade route between Mohave Indian villages on the Colorado River and settlements in coastal Southern California.

History

Starting from Mohave villages along the Colorado River in the upper Mohave Valley, t ...

that would become the western portion of the Old Spanish Trail. Upon reaching the San Bernardino Valley

The San Bernardino Valley ( es, Valle de San Bernardino) is a valley in Southern California located at the south base of the Transverse Ranges. It is bordered on the north by the eastern San Gabriel Mountains and the San Bernardino Mountains; ...

of California, Smith and Abraham LaPlant borrowed horses from a rancher and rode to the San Gabriel Mission on November 27, 1826, to present themselves to its director, Father José Bernardo Sánchez

Father José Bernardo Sánchez (September 7, 1778 – January 15, 1833) was a Spanish missionary in colonial Mexico and Alta California.

Early life

Born in Robledillo de Mohernando, Old Castile, Spain, Sánchez became a Franciscan on October ...

, who received them warmly.

San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the List of United States cities by population, eigh ...

for an interview with Governor José María Echeandía

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , is an old vernacul ...

about his party's status in the country. Echeandía, surprised and suspicious of the Americans' unauthorized entrance into California, had Smith arrested, believing him to be a spy. Accompanied by LaPlant, Smith's Spanish interpreter, Smith was taken to San Diego while the remainder of the party remained at the mission. Echeandía detained Smith for about two weeks, demanding that he turn over his journal and maps. Smith requested permission to travel north to the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

on a coastal route, where known paths could take his party back to United States territory. Upon intercession of American sea Captain W.H. Cunningham of Boston on the ship ''Courier'', Smith was released by Echeandía to reunite with his men. Echeandía ordered Smith and his party to leave California by the same route they entered, forbidding him to travel north along the coast to Bodega Bay

Bodega Bay ( es, Bahía Bodega) is a shallow, rocky inlet of the Pacific Ocean on the coast of northern California in the United States. It is approximately across and is located approximately northwest of San Francisco and west of Santa Ros ...

but giving Smith permission to purchase needed supplies for an eastern overland return journey. Smith boarded the ''Courier'' sailing from San Diego to San Pedro, to meet his men.

After waiting for almost another month for an exit visa and then spending at least two more weeks breaking the horses they had purchased for the return trip, Smith's party departed the mission communities of California in mid-February 1827. The party returned on the path it had arived, but once outside the Mexican settlements, Smith convinced himself he had complied with Echeandía's order to leave by the same route he had entered, and the party veered north crossing over into the Central Valley. The party ultimately made its way to the Kings River on February 28 and began trapping beaver. The party kept working its way north, encountering hostile Maidu

The Maidu are a Native American people of northern California. They reside in the central Sierra Nevada, in the watershed area of the Feather and American rivers. They also reside in Humbug Valley. In Maiduan languages, ''Maidu'' means "man."

...

s. By early May 1827, Smith and his men had traveled north looking for the Buenaventura River, but they found no break in the Sierra Nevada range through which it could have flowed from the Rocky Mountains. On December 16, 1826, Smith had written in a letter to the United States ambassador plenipotentiary to Mexico his plans to "follow up on of the largest Riv(ers) that emptied into the (San Francisco) Bay cross the mon (mountains) at its head and from thence to our deposit on the Great Salt Lake" and appeared to be following that plan. They followed the Cosumnes River

The Cosumnes River is a river in northern California in the United States. It rises on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada and flows approximately into the Central Valley, emptying into the Mokelumne River in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Del ...

(the northernmost tributary of the San Joaquin River

The San Joaquin River (; es, Río San Joaquín) is the longest river of Central California. The long river starts in the high Sierra Nevada, and flows through the rich agricultural region of the northern San Joaquin Valley before reaching Suis ...

) upstream, but veered off it to the north and crossed over to the American River

, name_etymology =

, image = American River CA.jpg

, image_size = 300

, image_caption = The American River at Folsom

, map = Americanrivermap.png

, map_size = 300

, map_caption ...

, a tributary of the Sacramento

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

that flowed into San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water from a ...

. They tried traveling up the canyon of the South Fork of the American to cross the Sierra Nevada but had to return because of deep snow. Unable to find a feasible path for the well-laden party to cross and faced with hostile indigenes, he was forced into a decision: since they did not have time to travel north to Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

and be on time for the 1827 rendezvous, they would backtrack to the Stanislaus River

The Stanislaus River is a tributary of the San Joaquin River in north-central California in the United States. The main stem of the river is long, and measured to its furthest headwaters it is about long. Originating as three forks in the high ...

and re-establish a camp there. Smith would take two men and some extra horses to get to the rendezvous as quickly as he could and return to his party with more men later in the year, and the group would continue on to the Columbia.

After a difficult crossing of the Sierra Nevada near

After a difficult crossing of the Sierra Nevada near Ebbetts Pass

Ebbetts Pass (el. ), named after John Ebbetts, is a high mountain pass through the Sierra Nevada range in Alpine County, California. Ebbetts is the eastern of two passes in the area traversed by State Route 4. The western pass is the Pacific Grad ...

, Smith and his two men passed around the south end of Walker Lake Several lakes are known as Walker Lake:

Canada

*Lake Walker in Quebec, Canada, the largest (by depth) lake in the province.

United States

*Walker Lake (Haines, Alaska)

*Walker Lake (Northwest Arctic, Alaska)

*Walker Lake (Prince of Wales-Outer ...

. After meeting with the only mounted natives that they would encounter until they reached the Salt Lake Valley

Salt Lake Valley is a valley in Salt Lake County in the north-central portion of the U.S. state of Utah. It contains Salt Lake City and many of its suburbs, notably Murray, Sandy, South Jordan, West Jordan, and West Valley City; its total po ...

, they continued east across central Nevada, straight across the Great Basin Desert as the summer heat hit the region. Neither they nor their horses or mules could find adequate food. As the horses gave out, they were butchered for whatever meat the men could salvage. After two days without water, Robert Evans collapsed near the Nevada–Utah border and could go no further, but some natives Smith encountered gave them some food and told him where to find water, which he took back to Evans and revived him. As the three approached the Great Salt Lake, they again were unable to find water, and Evans collapsed again. Smith and Silas Gobel found a spring and again took back water to Evans. Finally, the men came to the top of a ridge from which they saw the Great Salt Lake to the north, a "joyful sight" to Smith. By this time they had one horse and one mule remaining. They reached and crossed the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

. Local natives told him the whites were gathered farther north at "the Little Lake" ( Bear Lake on the border between present-day Utah and Idaho). Smith borrowed a fresh horse from them and rode ahead of the other two men, reaching the rendezvous on July 3. The mountain men celebrated Smith's arrival with a cannon salute, for they had given up him and his party for lost.

Third Rendezvous of 1827 and second trip to California, 1827–28

As agreed, Ashley had sent provisions for the rendezvous, and his men took back of Smith, Jackson & Sublette furs and a letter from Smith to William Clark, then in the office of the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the region west of the

As agreed, Ashley had sent provisions for the rendezvous, and his men took back of Smith, Jackson & Sublette furs and a letter from Smith to William Clark, then in the office of the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the region west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, describing what he had observed the previous year. Smith left to rejoin the men he had left in California almost immediately after the rendezvous. He was accompanied by 18 men and two French-Canadian women, following much of the same route as the previous year. In the ensuing year, the Mojave along the Colorado River who had been so welcoming the previous year had clashed with trappers from Taos

Taos or TAOS may refer to:

Places

* Taos, Missouri, a city in Cole County, Missouri, United States

* Taos County, New Mexico, United States

** Taos, New Mexico, a city, the county seat of Taos County, New Mexico

*** Taos art colony, an art colo ...

and were set on revenge against the whites. While crossing the river, Smith's party was attacked; 10 men, including Silas Gobel, were killed, and the two women were taken captive. Smith and the eight surviving men, one badly wounded from the fighting, prepared to make a desperate stand on the west bank of Colorado River

The Colorado River ( es, Río Colorado) is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and northern Mexico. The river drains an expansive, arid drainage basin, watershed that encompasses parts of ...

, having made a makeshift breastwork out of trees and fashioned lances by attaching butcher knives to light poles. The men still had five guns among them, and as the Mojave began to approach, Smith ordered his men to fire on those within range. Two Mojaves were shot and killed, one was wounded, and the remaining attackers fled. Before the Mojave could regroup, Smith and eight other surviving men retreated on foot across the Mojave Desert on the Mohave Trail to the San Bernardino Valley.

Smith and the other survivors were again well received in San Gabriel. The party moved north to meet with the group that had been left in the

Smith and the other survivors were again well received in San Gabriel. The party moved north to meet with the group that had been left in the San Joaquin Valley

The San Joaquin Valley ( ; es, Valle de San Joaquín) is the area of the Central Valley of the U.S. state of California that lies south of the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and is drained by the San Joaquin River. It comprises seven c ...

, reuniting with them on September 19, 1827. Unlike in San Gabriel, they were coolly received by the priests at Mission San José Mission San José may refer to:

*Mission San José (California), a Spanish mission in Fremont, California

* Mission San Jose, Fremont, California, a neighborhood

* Mission San Jose High School, a high school in Fremont, California

*Mission San José ...

, who had already received warning of Smith's renewed presence in the area. Smith's party also visited the settlements at Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under both ...

and Yerba Buena

Yerba buena or hierba buena is the Spanish name for a number of aromatic plants, most of which belong to the mint family. ''Yerba buena'' translates as "good herb". The specific plant species regarded as ''yerba buena'' varies from region to regi ...

(San Francisco).

Governor Echeandía, who was at the time in Monterey (capital of Alta California), once again arrested Smith, this time along with his men. Yet despite the breach of trust, the governor once again released Smith after several English-speaking residents vouched for him, including John B. R. Cooper and William Edward Petty Hartnell

William Edward Petty Hartnell (April 24, 1798 – February 2, 1854), later known by his Spanish name Don Guillermo Arnel, was a merchant, schoolmaster, and government official in California. He arrived in California in 1822 as a trader, where he ...

in Monterey. After posting a $30,000 bond, Smith received a passport, on the same promise – to leave the province immediately and not to return. Also as before, Smith and his party remained in California hunting in the Sacramento Valley for several months. Upon reaching the northern edge of the valley, the party scouted the route to the northeast afforded by the Pit River

The Pit River is a major river draining from northeastern California into the state's Central Valley. The Pit, the Klamath and the Columbia are the only three rivers in the U.S. that cross the Cascade Range.

The longest tributary of the Sacr ...

but determined it to be impassable, so veered northwest toward the Pacific coast to find the Columbia River and return to the Rocky Mountain region. Jedediah Smith became the first explorer to reach the Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been created by the Treaty of 1818, co ...

overland by traveling north on the California coast.

Trip to the Oregon Country

When Smith's party left Mexican Alta California and entered the Oregon Country, the

When Smith's party left Mexican Alta California and entered the Oregon Country, the Treaty of 1818

The Convention respecting fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves, also known as the London Convention, Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Convention of 1818, or simply the Treaty of 1818, is an international treaty signed in 1818 betw ...

allowed joint occupation between Britain and the United States. In the Oregon Country, Smith's party, then numbering 19 and over 250 horses, came into contact with the Umpqua people

The Umpqua people are an umbrella group of several distinct tribal entities of Native Americans of the Umpqua Basin in present-day south central Oregon in the United States. The area south of Roseburg is now known as the Umpqua Valley.

At least ...

. The tribes along the coast had monitored the party's progress, passing news of conflicts between the group and indigenes, and the Umpqua were wary. One of them stole an ax, and Smith's party treated some of the Umpqua very harshly to force the thief to return it. On July 14, 1828, while Smith, John Turner

John Napier Wyndham Turner (June 7, 1929September 19, 2020) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 17th prime minister of Canada from June to September 1984. He served as leader of the Liberal Party of Canada and leader of t ...

and Richard Leland were scouting a trail north, his group was attacked in its camp on the Umpqua River

The Umpqua River ( ) on the Pacific coast of Oregon in the United States is approximately long. One of the principal rivers of the Oregon Coast and known for bass and shad, the river drains an expansive network of valleys in the mountains west ...

.

On the night of August 8, 1828, Arthur Black arrived at the gate of Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) post at Fort Vancouver, badly wounded and almost destitute of clothing. He believed himself to be the only survivor of the men at camp but did not know of the fate of Smith and the two others. Chief Factor John McLoughlin

John McLoughlin, baptized Jean-Baptiste McLoughlin, (October 19, 1784 – September 3, 1857) was a French-Canadian, later American, Chief Factor and Superintendent of the Columbia District of the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver fro ...

, superintendent at the fort, sent word to the local tribes that they would be rewarded if they brought Smith and his men to the fort unharmed, and began organizing a search party for them. McLoughlin died in 1857, and his memoirs can be found in their entirety in Smith and the two others, having been alerted to the attack, had climbed a hill above the camp and witnessed the massacre; they arrived at the fort two days after Black. In 1824, Governor-in-Chief of the HBC, George Simpson, had put McLoughlin in charge of building and operating Fort Vancouver. Smith and his party represented American interests in the fur trade.

McLoughlin sent Alexander McLeod

Alexander McLeod was a Scottish-Canadian who served as sheriff in Niagara, Ontario. After the Upper Canada Rebellion, he boasted that he had partaken in the 1837 Caroline Affair, the sinking of an American steamboat that had been supplying Wi ...

south with Smith, Black, Turner, and Leland, and several HBC men to rescue any other men that had been in the camp that had possibly survived, and their goods. After recovering several horses in bad condition, Black and Leland remained with some HBC men to care for them, and the HBC horses and Smith, Turner, and 18 HBC men proceeded to the massacre site. On October 28, they reached it and found 11 decomposed bodies, which they buried. They ultimately confirmed that all 15 of the unaccounted-for men had died and recovered 700 beaver skins and 39 horses, as well as Harrison Rogers' journals.

When Smith returned to Fort Vancouver ten days later, he met with Governor Simpson to discuss the possibility of the HBC buying Smith's recovered property. Governor Simpson paid Smith $2,600 for the horses and furs, and in return Smith assured that his American fur trade company would confine its operations to the region east of the Great Divide. Smith remained at Fort Vancouver until March 12, 1829, when he and Arthur Black traveled back east to meet up with his partners.

Blackfeet expedition, 1829–30

In 1829, Captain Smith personally organized a fur trade expedition into the

In 1829, Captain Smith personally organized a fur trade expedition into the Blackfeet

The Blackfeet Nation ( bla, Aamsskáápipikani, script=Latn, ), officially named the Blackfeet Tribe of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation of Montana, is a federally recognized tribe of Siksikaitsitapi people with an Indian reservation in Monta ...

territory. Smith was able to capture a good cache of beaver before being repulsed by hostile Blackfeet. Jim Bridger

James Felix "Jim" Bridger (March 17, 1804 – July 17, 1881) was an American mountain man, trapper, Army scout, and wilderness guide who explored and trapped in the Western United States in the first half of the 19th century. He was known as Old ...

served as a riverboat pilot on the Powder River during the profitable expedition. In the four years of western fur trapping, Smith, Jackson, and Sublette were able to make a substantial profit and, at the 1830 rendezvous on the Wind River, they sold their company to Tom Fitzpatrick, Milton Sublette

Milton Green Sublette (c. 1801–1837), was an American frontiersman, trapper, fur trader, explorer, and mountain man. He was the second of five Sublette brothers prominent in the western fur trade; William, Andrew, and Solomon. Milton was one of ...

, Jim Bridger, Henry Fraeb Henry Fraeb, also called Frapp, was a mountain man, fur trader, and trade post operator of the American West, operating in the present-day states of Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana.

__TOC__

Early life

Fraeb, of German heritage, was from St. Louis, ...

, and John Baptiste Gervais who renamed it the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

Return to St. Louis

After Smith's return to St. Louis in 1830, he and his partners wrote a letter on October 29 to Secretary of War Eaton, who at the time was involved in a notorious Washington cabinet scandal known as the

After Smith's return to St. Louis in 1830, he and his partners wrote a letter on October 29 to Secretary of War Eaton, who at the time was involved in a notorious Washington cabinet scandal known as the Petticoat Affair

The Petticoat affair (also known as the Eaton affair) was a political scandal involving members of President Andrew Jackson's Cabinet and their wives, from 1829 to 1831. Led by Floride Calhoun, wife of Vice President John C. Calhoun, these wo ...

and informed Eaton of the "military implications" in terms of the British allegedly alienating the indigene population towards any American trappers in the Pacific Northwest. According to biographer Dale L. Morgan, Smith's letter was "a clear sighted statement of the national interest". The letter also included a description of Fort Vancouver and described how the British were in the process of making a new fort at the time of Smith's visit in 1829. Smith believed the British were attempting to establish a permanent settlement in the Oregon Country.

Smith had not forgotten the financial struggles of his family in Ohio. After making a sizable profit from the sale of furs, over $17,000 ($500,000 in 2021), Smith sent $1,500 to his family in Green Township, whereupon his brother Ralph bought a farm. Smith also bought a house on First Avenue in St. Louis to be shared with his brothers. Smith bought two African slaves to take care of the property in St. Louis.

The partners' busy schedules in St. Louis also found them and Samuel Parkman making a map of their discoveries in the West, to which Smith was the major contributor. On March 2, 1831, Smith wrote another letter to Eaton, now a few months away from resigning because of the Petticoat Affair, referencing the map and requesting to launch a federally funded exploration expedition similar to the Lewis & Clark expedition. Smith requested that Reuben Holmes, a West Point graduate and military officer, would lead the expedition.

Smith and his partners were also preparing to join into the supply trade known as the " commerce of the prairies". At the request of William H. Ashley, Smith Jackson and Sublette received a passport from Senator Thomas Hart Benton on March 3, 1831, the day after Smith wrote his letter to Eaton, and they began forming a company of 74 men, twenty-two wagons, and a "six-pounder" artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

for protection.

Death

Having no response from Eaton, Smith joined his partners and left St. Louis to trade in Santa Fe on April 10, 1831. Smith was leading the caravan on the

Having no response from Eaton, Smith joined his partners and left St. Louis to trade in Santa Fe on April 10, 1831. Smith was leading the caravan on the Santa Fe Trail

The Santa Fe Trail was a 19th-century route through central North America that connected Franklin, Missouri, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. Pioneered in 1821 by William Becknell, who departed from the Boonslick region along the Missouri River, th ...

on May 27, 1831, when he left the group to scout for water near the Lower Spring on the Cimarron River in present-day southwest Kansas. He never returned to the group. The remainder of the party proceeded on to Santa Fe hoping Smith would rendezvous with them, but he never did. They arrived in Santa Fe on July 4, 1831, and shortly thereafter members of the party discovered a comanchero

The Comancheros were a group of 18th- and 19th-century traders based in northern and central New Mexico. They made their living by trading with the nomadic Great Plains Indian tribes in northeastern New Mexico, West Texas, and other parts of the ...

with some of Smith's personal belongings. It was relayed that Smith had encountered and communicated with a group of Comancheros just prior to his approaching a group of Comanche

The Comanche or Nʉmʉnʉʉ ( com, Nʉmʉnʉʉ, "the people") are a Native American tribe from the Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the federally recognized Comanche Nation, headquartered in La ...

. Smith tried to negotiate with the Comanche, but they surrounded him in preparation for an attack.

Most likely, the death of Jedediah Smith occurred in Northern Mexico Territory, south of present-day Ulysses

Ulysses is one form of the Roman name for Odysseus, a hero in ancient Greek literature.

Ulysses may also refer to:

People

* Ulysses (given name), including a list of people with this name

Places in the United States

* Ulysses, Kansas

* Ulysse ...

, Grant County, Kansas

Grant County (county code GT) is a county located in the U.S. state of Kansas. As of the 2020 census, the county population was 7,352. Its county seat and only city is Ulysses. Both the county and its seat are named after Ulysses S. Grant, 18t ...

. According to Smith's grand-nephew, Ezra Delos Smith, there were 20 Comanches in the group. Smith attempted to conciliate with them until the Comanches scared his horse and shot him in the left shoulder with an arrow. Smith fought back, ultimately killing the chief of the warriors. The version written by Austin Smith, Jedediah's brother, in a letter to their brother Ira four months after Jedediah's death says that Jedediah had killed the "head Chief," but nothing about any other Comanche being wounded or killed. Josiah Gregg

Josiah Gregg (19 July 1806 – 25 February 1850) was an American merchant, explorer, naturalist, and author of '' Commerce of the Prairies'', about the American Southwest and parts of northern Mexico. He collected many previously undescribed pla ...

wrote in 1844 that Smith "struggled bravely to the last; and, as the Indians themselves have ''since'' related, killed two or three of their party before he was overpowered." Ezra Delos Smith stated that his grand-uncle had fought so valiantly that the Comanche believed "he had been more than mortal, and that he could be immortal it would be better to propitiate his spirit; so they did not mutilate his body, but later gave it the same funeral rites they gave its chief" Austin Smith, who along with another Smith brother, Peter, was a member of the caravan, was able to retrieve Jedediah Smith's rifle and pistols that the Indians had taken and traded to the Comancheros.

Aftermath

In the aftermath of Smith's death, PresidentAndrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

, during his second term in 1836, launched the federally-funded oceanic United States Exploring Expedition

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands conducted by the United States. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby ...

, led by Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes (April 3, 1798 – February 8, 1877) was an American naval officer, ship's captain, and explorer. He led the United States Exploring Expedition (1838–1842).

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), he commanded ' during the ...

, from 1838 to 1842. One of the expedition's accomplishments was the exploration of the Pacific Northwest and to lay claim on the Oregon Country, which Smith had previously explored, dominated by the British Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River. The federally-funded overland exploration of the West that Smith had requested in 1831 took place starting in 1842 commanded by Lieutenant John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

under President John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president dire ...

and President James K. Polk. It was Frémont's first two documented and published explorations of the West during the 1840s that opened the West to American expansion. Frémont was popularly known as the ''Pathfinder'' until the late 19th century, while Smith's life and reputation were nearly forgotten by his countrymen. In 1846, the disputed joint occupancy of Britain and the United States of the Oregon Country where Smith stayed at Fort Vancouver was ended by the Oregon Treaty. In 1848, Mexico ceded California (where Smith had twice been arrested by Governor Echeandía) to the United States under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ending the Mexican–American War.

Personal characteristics and beliefs

Jedediah Smith was no ordinary mountain man. He had a dry, not raucous, sense of humor and was not known to use the profanity common to his peers. Smith's immediate family were practicing Christians; his younger brother Benjamin was named after a History of Methodism in the United States, Methodist circuit preacher, and his letters indicate his own Christian beliefs. Although after his death the legend of Smith as a "Bible-toter" and a missionary grew, assertions that he carried a Bible with him in the wilderness have no basis in any accounts by him or his companions, and the only documentation of any public demonstration of faith was a prayer said at the burial of one of the Arikara massacre victims. However, neither do those accounts speak of him drinking alcohol to excess or bedding Native American women, indicating he had the discipline often associated with a strict moral code. He owned at least two slaves, which conflicted with his northern Methodist upbringing, and his behavior was not always honorable when dealing with those he considered his antagonists. He was known to be physically strong, cool under pressure, extremely skilled at surviving in the wild, and possessed extraordinary leadership skills. Smith's true character is an enigma open to interpretation.Views of Native Americans

While traveling throughout the American West, Smith's policy with the Native Americans was to maintain friendly relations with gifts and exchanges, learning from their cultures. As he traveled through northern California for the first time, then part of Mexican territory Alta California, he tried to maintain that policy, but the situation quickly deteriorated. The Maidu were fearful and defensive, and Smith's men killed at least seven of them upon his orders when they refused peaceful advances and demonstrated aggressive behaviors. He later wrote that they were "the lowest intermediate link between man and the Brute creation". Later, during his trek across the Great Basin, he said of the desert indigenes he came upon "children of nature...unintelligent type of beings...They form a connecting link between the animal and intellectual creation..." Upon returning to Mexican California, even after suffering the Mojave massacre, he continued to try to maintain good relations, punishing two of his men, albeit lightly, who had unnecessarily killed one native and wounded another. But as the party continued north, the natives continued the aggressive actions, and Smith's men wounded at least two more and three were killed. By the time the party reached the Umpqua River in the British-American shared Oregon Country, their tolerance was at an ebb, leading to the ax incident and resulting in disastrous consequences.Historical reputation

Smith for the most part was forgotten by his countrymen as a historical figure for over 75 years after his death. In 1853, Peter Skene Ogden had written about the Umpqua massacre in ''Traits of American Indian Life and Character by a Fur Trader'', and the Sons and Daughters of Oregon Pioneers, Oregon Pioneers Association and Hubert Howe Bancroft wrote versions of it in 1876 and 1886, respectively. There are mentions of him in memoirs by other fur trappers, and mentions by George Gibbs (ethnologist), George Gibbs and Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, F. V. Hayden in their reports. ''Recollection of a Septuagenarian'' by William Waldo (California politician), William Waldo, published by the Missouri Historical Society in 1880, discussed Smith, focusing on hearsay evidence of his piety. There was no mention of Smith in the 1891 volume 5 publication of ''Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography'' edited by James Grant Wilson and John Fiske (philosopher), John Fiske. The first known publication solely about Smith was in the 1896 ''Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California''.J. M. Guinn, ''Captain Jedediah Smith. The Pathfinder of the Sierras'' Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles Vol. 3, No. 4 (1896), pp. 45–53, 78 In 1902, Hiram M. Chittenden wrote of him extensively in ''The American Fur Trade of the West'' The same year Frederick Samuel Dellenbaugh wrote about Smith's exploits with the Mojave Indians in his book ''The Romance of the Colorado River: The Story of Its Discovery in 1540 with an Account of Later Explorations''. Smith, however, again was not listed in the 1906 volume 9 publication of American Biographical Society's ''Biographical Dictionary of America'', edited by Rossiter Johnson. In 1908, John Neihardt, John G. Neihardt and Doane Robinson lamented the obscurity of Smith; afterward, more extensive efforts were initiated to publicize his accomplishments. In 1912, an article about Smith written by a grand-nephew, Ezra Delos Smith of Meade, Kansas, was published by the Kansas Historical Society. Five years later, Smith's status as a historical figure was further revived by Harrison Clifford Dale's boo''The Ashley-Smith Explorations and the Discovery of a Central Route to the Pacific, 1822–1829: With the Original Journals''