Japanese Sword Construction on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Japanese swordsmithing is the labour-intensive bladesmithing process developed in Japan for forging traditionally made bladed weapons ( ''nihonto'') including ''

Japanese swordsmithing is the labour-intensive bladesmithing process developed in Japan for forging traditionally made bladed weapons ( ''nihonto'') including ''

Mitsuru Tate (2005). Tetsu-to-Hagane Vol. 91. The Iron and Steel Institute of Japan.たたらの歴史 たたら製鉄の進歩 (Progress of Tatara Iron Making).

Yasugi Cityたたら」の発祥と発展 (Changes in Japanese Tatara Iron Making Technology).

Yasugi Cityたたら製鉄の歴史と仕組み.

Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken World Currently, ''tamahagane'' is only made three or four times a year by The Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords and Hitachi Metals during winter in a wood building and is only sold to master swordsmiths.

The forging of a Japanese blade typically took many days or weeks and was considered a sacred art, traditionally accompanied by a large panoply of

The forging of a Japanese blade typically took many days or weeks and was considered a sacred art, traditionally accompanied by a large panoply of

Japanese swordsmithing is the labour-intensive bladesmithing process developed in Japan for forging traditionally made bladed weapons ( ''nihonto'') including ''

Japanese swordsmithing is the labour-intensive bladesmithing process developed in Japan for forging traditionally made bladed weapons ( ''nihonto'') including ''katana

A is a Japanese sword characterized by a curved, single-edged blade with a circular or squared guard and long grip to accommodate two hands. Developed later than the '' tachi'', it was used by samurai in feudal Japan and worn with the edge f ...

'', ''wakizashi

The is one of the traditionally made Japanese swords (''nihontō'') worn by the samurai in feudal Japan.

History and use

The production of swords in Japan is divided into specific time periods:

'', ''tantō

A is one of the traditionally made Japanese swords (Commons:Nihonto, ''nihonto'') that were worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. The tantō dates to the Heian period, when it was mainly used as a weapon but evolved in design over the year ...

'', ''yari

is the term for a traditionally-made Japanese blade (日本刀; nihontō) in the form of a spear, or more specifically, the straight-headed spear. The martial art of wielding the is called .

History

The forerunner of the is thought to be a ...

'', ''naginata

The ''naginata'' (, ) is a pole weapon and one of several varieties of traditionally made Japanese blades (''nihontō''). ''Naginata'' were originally used by the samurai class of feudal Japan, as well as by ashigaru (foot soldiers) and sōhei ...

'', ''nagamaki

The is a type of traditionally made Japanese sword (''nihontō'') with an extra long handle, used by the samurai class of feudal Japan.Friday 2004, p. 88.

History

It is possible that nagamaki were first produced during the Heian period (794 to ...

'', ''tachi

A is a type of traditionally made Japanese sword (''nihonto'') worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. ''Tachi'' and ''katana'' generally differ in length, degree of curvature, and how they were worn when sheathed, the latter depending on t ...

'', '' nodachi'', ''ōdachi

The (large/great sword) or ''nodachi'' (野太刀, field sword) is a type of traditionally made Japanese sword (日本刀, nihontō) used by the samurai class of feudal Japan. The Chinese equivalent of this type of sword in terms of weight a ...

'', ''kodachi

A , literally translating into "small or short ''tachi'' (sword)", is one of the traditionally made Japanese swords (''nihontō'') used by the samurai class of feudal Japan. Kodachi are from the early Kamakura period (1185–1333) and are in the ...

'', and ''ya'' (arrow).

Japanese sword blades were often forged with different profiles, different blade thicknesses, and varying amounts of grind

A blade's grind is its cross-sectional shape in a plane normal to the edge. Grind differs from blade profile, which is the blade's cross-sectional shape in the plane containing the blade's edge and the centre contour of the blade's back ( ...

. ''Wakizashi'' and ''tantō'' were not simply scaled-down ''katana'' but were often forged without a ridge (''hira-zukuri'') or other such forms which were very rare on ''katana''.

Traditional methods

Steel production

The steel used in sword production is known as , or "jewel steel" (''tama'' – ball or jewel, ''hagane'' – steel). ''Tamahagane'' is produced fromiron sand

Ironsand, also known as iron-sand or iron sand, is a type of sand with heavy concentrations of iron. It is typically dark grey or blackish in colour.

It is composed mainly of magnetite, Fe3O4, and also contains small amounts of titanium, silic ...

, a source of iron ore, and mainly used to make samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They h ...

swords, such as the ''katana

A is a Japanese sword characterized by a curved, single-edged blade with a circular or squared guard and long grip to accommodate two hands. Developed later than the '' tachi'', it was used by samurai in feudal Japan and worn with the edge f ...

'', and some tools.

The smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a ...

process used is different from the modern mass production of steel. A clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

vessel about tall, long, and wide is constructed. This is known as a ''tatara''. After the clay tub has set, it is fired until dry. A charcoal fire is started from soft pine charcoal. Then the smelter will wait for the fire to reach the correct temperature. At that point he will direct the addition of iron sand known as ''satetsu''. This will be layered in with more charcoal and more iron sand over the next 72 hours. Four or five people are needed to constantly work on this process. It takes about a week to build the ''tatara'' and complete the iron conversion to steel. Because the charcoal cannot exceed the melting point of iron, the steel is not able to become fully molten, and this allows both high and low carbon material to be created and separated once cooled. When complete, the ''tatara'' is broken to remove the steel bloom, known as a ''kera''. At the end of the process the ''tatara'' will have consumed about of ''satetsu'' and of charcoal leaving about of ''kera'', from which less than a ton of ''tamahagane'' can be produced. A single ''kera'' can typically be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, making it many times more expensive than modern steels.

Japanese ''tatara'' steelmaking process using ironsand started in Kibi Province

was an ancient province or region of Japan, in the same area as Okayama Prefecture and eastern Hiroshima Prefecture. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "''Kibi''" in . It was sometimes called .

It was divided into Bizen (備前), Bitchū (� ...

in the sixth century and spread throughout Japan, using a unique Japanese low box-shaped furnace different from the Chinese and Korean styles. From the Middle Ages, as the size of furnaces became larger and the underground structure became more complicated, it became possible to produce a large amount of steel of higher quality, and in the Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was characte ...

, the underground structure, the blowing method, and the building were further improved to complete ''tatara'' steelmaking process using the same method as modern ''tatara'' steelmaking. With the introduction of Western steelmaking technology in the Meiji period

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization ...

, ''tatara'' steelmaking declined and stopped for a while in the Taisho period, but in 1977 The Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords restored ''tatara'' steelmaking in the Shōwa era and new ''tamahagane'' refined by ''tatara'' steelmaking became available for making Japanese swords.History of Iron and Steel Making Technology in Japan ーMainly on the smelting of iron sand by Tataraー.Mitsuru Tate (2005). Tetsu-to-Hagane Vol. 91. The Iron and Steel Institute of Japan.たたらの歴史 たたら製鉄の進歩 (Progress of Tatara Iron Making).

Yasugi Cityたたら」の発祥と発展 (Changes in Japanese Tatara Iron Making Technology).

Yasugi Cityたたら製鉄の歴史と仕組み.

Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken World Currently, ''tamahagane'' is only made three or four times a year by The Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords and Hitachi Metals during winter in a wood building and is only sold to master swordsmiths.

Construction

The forging of a Japanese blade typically took many days or weeks and was considered a sacred art, traditionally accompanied by a large panoply of

The forging of a Japanese blade typically took many days or weeks and was considered a sacred art, traditionally accompanied by a large panoply of Shinto

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shintois ...

religious rituals. As with many complex endeavors, several artists were involved. There was a smith to forge the rough shape, often a second smith (apprentice) to fold the metal, a specialist polisher, and even a specialist for the edge. Often, there were sheath, hilt, and handguard specialists as well.

Forging

The steel bloom, or ''kera'', that is produced in the ''tatara'' contains steel that varies greatly in carbon content, ranging fromwrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" ...

to pig iron. Three types of steel are chosen for the blade; a very low carbon steel called ''hocho-tetsu'' is used for the core of the blade (''shingane''). The high carbon steel (''tamahagane''), and the remelted pig iron (cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impur ...

or ''nabe-gane''), are combined to form the outer skin of the blade (''kawagane'')."A History of Metallography", by Cyril Smith Only about 1/3 of the ''kera'' produces steel that is suitable for sword production.

The best known part of the manufacturing process is the folding of the steel, where the swords are made by repeatedly heating, hammering and folding the metal. The process of folding metal to improve strength and remove impurities is frequently attributed to specific Japanese smiths in legends. The folding removes impurities and helps even out the carbon content, while the alternating layers combine hardness with ductility to greatly enhance the toughness.

In traditional Japanese sword making, the low-carbon iron is folded several times by itself, to purify it. This produces the soft metal to be used for the core of the blade. The high-carbon steel and the higher-carbon cast-iron are then forged in alternating layers. The cast-iron is heated, quenched in water, and then broken into small pieces to help free it from slag. The steel is then forged into a single plate, and the pieces of cast-iron are piled on top, and the whole thing is forge welded into a single billet, which is called the ''age-kitae'' process. The billet is then elongated, cut, folded, and forge welded again. The steel can be folded transversely (from front to back), or longitudinally (from side to side). Often both folding directions are used to produce the desired grain pattern. This process, called the ''shita-kitae'', is repeated from 8 to as many as 16 times. After 20 foldings (220, or 1,048,576 individual layers), there is too much diffusion in the carbon content. The steel becomes almost homogeneous in this respect, and the act of folding no longer gives any benefit to the steel.''A History of Metallography'' by Cyril Smith - The MIT Press 1960 Page 53-54 Depending on the amount of carbon introduced, this process forms either the very hard steel for the edge (''hagane'') or the slightly less hardenable spring steel (''kawagane'') which is often used for the sides and the back.

During the last few foldings, the steel may be forged into several thin plates, stacked, and forge welded into a brick. The grain of the steel is carefully positioned between adjacent layers, with the configuration dependent on the part of the blade for which the steel will be used.

Between each heating and folding, the steel is coated in a mixture of clay, water and straw-ash to protect it from oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a ...

and carburization. This clay provides a highly reducing environment

A reducing atmosphere is an atmospheric condition in which oxidation is prevented by removal of oxygen and other oxidizing gases or vapours, and which may contain actively reducing gases such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and gases such as hydro ...

. At around , the heat and water from the clay promote the formation of a wustite layer, which is a type of iron oxide formed in the absence of oxygen. In this reducing environment, the silicon in the clay reacts with wustite to form fayalite

Fayalite (, commonly abbreviated to Fa) is the iron-rich end-member of the olivine solid-solution series. In common with all minerals in the olivine group, fayalite crystallizes in the orthorhombic system (space group ''Pbnm'') with cell parame ...

and, at around , the fayalite becomes a liquid. This liquid acts as a flux, attracting impurities, and pulls out the impurities as it is squeezed from between the layers. This leaves a very pure surface which, in turn, helps facilitate the forge-welding process. Through the loss of impurities, slag, and iron in the form of sparks during the hammering, by the end of forging the steel may be reduced to as little as 1/10 of its initial weight. This practice became popular because of the use of highly impure metals, stemming from the low temperature yielded in the smelting process. The folding did several things:

* It provided alternating layers of differing hardness

In materials science, hardness (antonym: softness) is a measure of the resistance to localized plastic deformation induced by either mechanical indentation or abrasion. In general, different materials differ in their hardness; for example hard ...

. During quenching, the high carbon layers achieve greater hardness than the medium carbon layers. The hardness of the high carbon steels combine with the ductility

Ductility is a mechanical property commonly described as a material's amenability to drawing (e.g. into wire). In materials science, ductility is defined by the degree to which a material can sustain plastic deformation under tensile str ...

of the low carbon steels to form the property of toughness

In materials science and metallurgy, toughness is the ability of a material to absorb energy and plastically deform without fracturing.

* It eliminated any voids in the metal.

* It homogenized the metal within the layers, spreading the elements (such as carbon) evenly throughout the individual layers, increasing the effective strength by decreasing the number of potential weak points.

* It burned off many impurities, helping to overcome the poor quality of the raw steel.

* It created up to 65,000 layers, by continuously decarburizing the surface and bringing it into the blade's interior, which gives the swords their grain (for comparison see pattern welding).

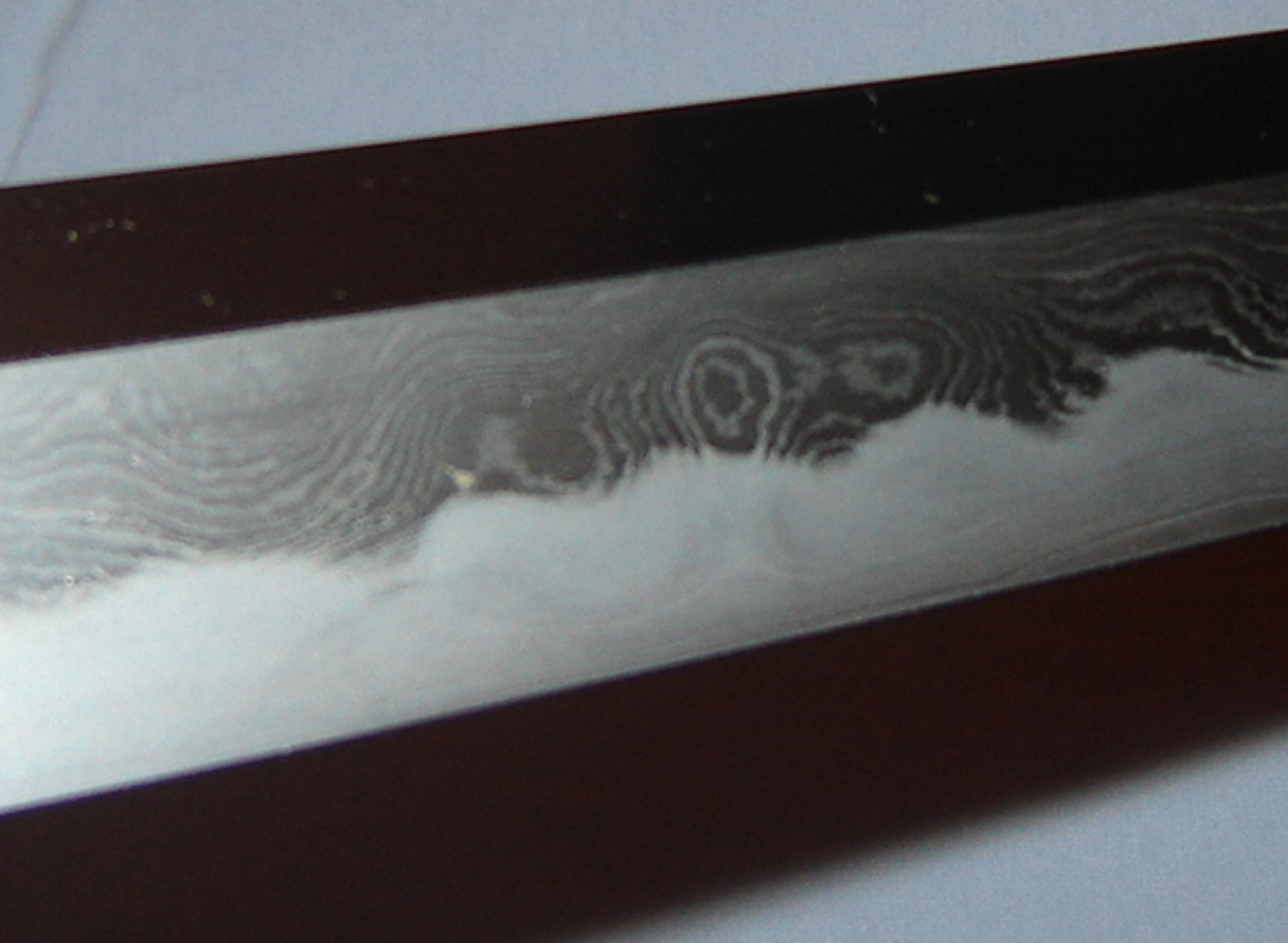

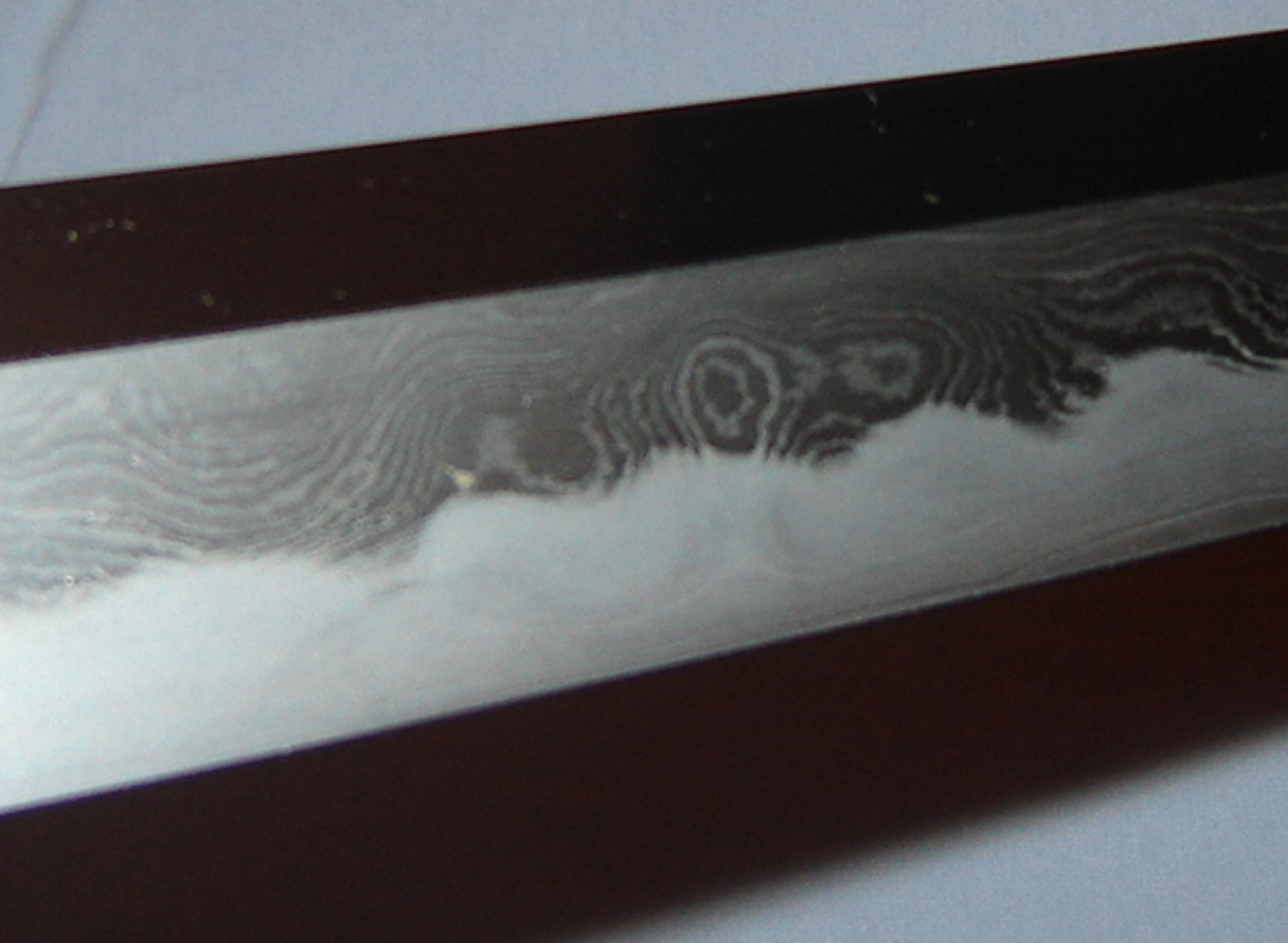

Generally, swords were created with the grain of the blade (''hada'') running down the blade like the grain on a plank of wood. Straight grains were called ''masame-hada'', wood-like grain ''itame,'' wood-burl grain ''mokume,'' and concentric wavy grain (an uncommon feature seen almost exclusively in the Gassan school) ''ayasugi-hada''. The difference between the first three grains is that of cutting a tree along the grain, at an angle, and perpendicular to its direction of growth (

''Globalizing the Prehistory of Japan: Language, Genes and Civilization'', Volume 6 of Routledge Studies in the Early History of Asia, Author Ann Kumar, Publisher Taylor & Francis US, 2009, , 9780710313133 P.23 The vast majority of modern ''katana'' and ''wakizashi'' are the ''maru'' type (sometimes also called ''muku'') which is the most basic, with the entire sword being composed of a single steel. However, with the use of modern steels, this does not cause the sword to be fragile, as in former days. The type is made using two steels, which are called ''hagane'' (edge steel) and ''shingane'' (core steel). ''Honsanmai'' and ''shihozume'' types add the third steel, called ''kawagane'' (skin steel). The many different ways in which a sword can be assembled varies from smith to smith. Sometimes the edge-steel is "drawn out" (hammered into a bar), bent into a 'U' shaped trough, and the very soft core steel is inserted into the harder piece. Then they are forge welded together and hammered into the basic shape of the sword. By the end of the process, the two pieces of steel are fused together but retain their differences in hardness. The more complex types of construction are typically only found in antique weapons, with the vast majority of modern weapons being composed of a single section, or at most two or three sections. Another way is to assemble the different pieces into a block, forge weld it together, and then draw out the steel into a sword so that the correct steel ends up in the desired place. This method is often used for the complex models, which allow for parrying without fear of damaging the side of the blade. To make ''honsanmai'' or ''shihozume'' types, pieces of hard steel are added to the outside of the blade in a similar fashion. The ''shihozume'' and ''soshu'' types are quite rare but added a rear support.

The mainstream of the swords from the Kofun period to the

The mainstream of the swords from the Kofun period to the

Having a single edge provides certain advantages; one being that the rest of the sword can be used to reinforce and support the edge. The Japanese style of sword-making takes full advantage of this. When forging is complete, the steel is not

Having a single edge provides certain advantages; one being that the rest of the sword can be used to reinforce and support the edge. The Japanese style of sword-making takes full advantage of this. When forging is complete, the steel is not

According to Smith, the different layers of steel are made visible during the polishing because of one or both of two reasons: 1) the layers have a variation in carbon content, or 2) they have variation in the content of slag inclusions. When the variation is from slag inclusions by themselves, there will not be a noticeable effect near the ''hamon'', where the ''yakiba'' meets the ''hira''. Likewise, there will be no appreciable difference in the local hardness of the individual layers. A difference in slag inclusions generally appears as layers that are somewhat pitted while the adjacent layers are not. In one of the first metallurgical studies, Professor Kuni-ichi Tawara suggests that layers of high slag may have been added for practical as well as decorative reasons. Although slag has a weakening effect on the metal, layers of high slag may have been added to diffuse vibration and dampen recoil, allowing easier use without a significant loss in toughness.''A History of Metallography'' by Cyril Stanley Smith -- MIT Press 1960 Page 46--47

However, when the patterns occur from a difference in carbon content, there will be distinct indications of this near the ''hamon'', because the steel with higher hardenability will become martensite beyond the ''hamon'' while the adjacent layers will turn into pearlite. This leaves a distinct pattern of bright ''nioi'', which appear as bright streaks or lines that follow the layers a short distance away from the ''hamon'' and into the ''hira'', giving the ''hamon'' a wispy or misty appearance. The patterns were most likely revealed during the polishing operation by using a method similar to

According to Smith, the different layers of steel are made visible during the polishing because of one or both of two reasons: 1) the layers have a variation in carbon content, or 2) they have variation in the content of slag inclusions. When the variation is from slag inclusions by themselves, there will not be a noticeable effect near the ''hamon'', where the ''yakiba'' meets the ''hira''. Likewise, there will be no appreciable difference in the local hardness of the individual layers. A difference in slag inclusions generally appears as layers that are somewhat pitted while the adjacent layers are not. In one of the first metallurgical studies, Professor Kuni-ichi Tawara suggests that layers of high slag may have been added for practical as well as decorative reasons. Although slag has a weakening effect on the metal, layers of high slag may have been added to diffuse vibration and dampen recoil, allowing easier use without a significant loss in toughness.''A History of Metallography'' by Cyril Stanley Smith -- MIT Press 1960 Page 46--47

However, when the patterns occur from a difference in carbon content, there will be distinct indications of this near the ''hamon'', because the steel with higher hardenability will become martensite beyond the ''hamon'' while the adjacent layers will turn into pearlite. This leaves a distinct pattern of bright ''nioi'', which appear as bright streaks or lines that follow the layers a short distance away from the ''hamon'' and into the ''hira'', giving the ''hamon'' a wispy or misty appearance. The patterns were most likely revealed during the polishing operation by using a method similar to

Almost all blades are decorated, although not all blades are decorated on the visible part of the blade. Once the blade is cool and the mud is scraped off, the blade has designs and grooves cut into it. One of the most important markings on the sword is performed here: the file markings. These are cut into the

Almost all blades are decorated, although not all blades are decorated on the visible part of the blade. Once the blade is cool and the mud is scraped off, the blade has designs and grooves cut into it. One of the most important markings on the sword is performed here: the file markings. These are cut into the

Is Stainless Steel Suitable for Swords?

Sword Forum online magazine, March 1999 With a normal

Construction of the Shinken in the Modern Age

Japanese Sword Polishing Techniques

Japanese Sword History

What is Tamahagane ?

Tamahagane – Unique Metal for Unique Japanese Swords

{{DEFAULTSORT:Japanese Swordsmithing

mokume-gane

is a Japanese metalworking procedure which produces a mixed-metal laminate with distinctive layered patterns; the term is also used to refer to the resulting laminate itself. The term translates closely to "wood grain metal" or "wood eye metal" ...

) respectively, the angle causing the "stretched" pattern.

Assembly

In addition to folding the steel, high quality Japanese swords are also composed of various distinct sections of different types of steel. This manufacturing technique uses different types of steel in different parts of the sword to accentuate the desired characteristics in various parts of the sword beyond the level offered bydifferential heat treatment

Differential heat treatment (also called selective heat treatment or local heat treatment) is a technique used during heat treating to harden or soften certain areas of a steel object, creating a difference in hardness between these areas. There ar ...

.''Globalizing the Prehistory of Japan: Language, Genes and Civilization'', Volume 6 of Routledge Studies in the Early History of Asia, Author Ann Kumar, Publisher Taylor & Francis US, 2009, , 9780710313133 P.23 The vast majority of modern ''katana'' and ''wakizashi'' are the ''maru'' type (sometimes also called ''muku'') which is the most basic, with the entire sword being composed of a single steel. However, with the use of modern steels, this does not cause the sword to be fragile, as in former days. The type is made using two steels, which are called ''hagane'' (edge steel) and ''shingane'' (core steel). ''Honsanmai'' and ''shihozume'' types add the third steel, called ''kawagane'' (skin steel). The many different ways in which a sword can be assembled varies from smith to smith. Sometimes the edge-steel is "drawn out" (hammered into a bar), bent into a 'U' shaped trough, and the very soft core steel is inserted into the harder piece. Then they are forge welded together and hammered into the basic shape of the sword. By the end of the process, the two pieces of steel are fused together but retain their differences in hardness. The more complex types of construction are typically only found in antique weapons, with the vast majority of modern weapons being composed of a single section, or at most two or three sections. Another way is to assemble the different pieces into a block, forge weld it together, and then draw out the steel into a sword so that the correct steel ends up in the desired place. This method is often used for the complex models, which allow for parrying without fear of damaging the side of the blade. To make ''honsanmai'' or ''shihozume'' types, pieces of hard steel are added to the outside of the blade in a similar fashion. The ''shihozume'' and ''soshu'' types are quite rare but added a rear support.

Geometry (shape and form)

The mainstream of the swords from the Kofun period to the

The mainstream of the swords from the Kofun period to the Nara period

The of the history of Japan covers the years from CE 710 to 794. Empress Genmei established the capital of Heijō-kyō (present-day Nara). Except for a five-year period (740–745), when the capital was briefly moved again, it remained the c ...

was the straight single-edged sword called '' chokutō'', and the swords of Japanese original style and Chinese style were mixed. The cross-sectional shape of the Japanese sword was an isosceles triangular ''hira-zukuri'', and a sword with a cross-sectional shape called ''kiriha-zukuri'', with only the cutting edge side of a planar blade sharpened at an acute angle, gradually appeared. The swords until this period are called ''jōkotō'', and are often called separately from Japanese swords.Kazuhiko Inada (2020), ''Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords''. pp30-31.

The predecessor of the Japanese sword has been called ''Warabitetō ( :ja:蕨手刀)''. In the middle of the Heian period

The is the last division of classical Japanese history, running from 794 to 1185. It followed the Nara period, beginning when the 50th emperor, Emperor Kanmu, moved the capital of Japan to Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto). means "peace" in Japanese ...

(794–1185), samurai improved on the Warabitetō to develop ''Kenukigata-tachi ( :ja:毛抜形太刀)'' -early Japanese sword-. ''Kenukigata-tachi'', which was developed in the first half of the 10th century, has a three-dimensional cross-sectional shape of an elongated pentagonal or hexagonal blade called ''shinogi-zukuri'' and a gently curved single-edged blade, which are typical features of Japanese swords. When a ''shinogi-zukuri'' sword is viewed from the side, there is a ridge line of the thickest part of the blade called ''shinogi'' between the cutting edge side and the back side. This ''shinogi'' contributes to lightening and toughening of the blade and high cutting ability. There is no wooden hilt attached to ''kenukigata-tachi'', and the tang

Tang or TANG most often refers to:

* Tang dynasty

* Tang (drink mix)

Tang or TANG may also refer to:

Chinese states and dynasties

* Jin (Chinese state) (11th century – 376 BC), a state during the Spring and Autumn period, called Tang (唐) b ...

(''nakago'') which is integrated with the blade is directly gripped and used. The term ''kenukigata'' is derived from the fact that the central part of tang is hollowed out in the shape of a tool to pluck hair (''kenuki'').Kazuhiko Inada (2020), ''Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords''. pp32-33. ''歴史人'' September 2020. p.50.

In the ''tachi

A is a type of traditionally made Japanese sword (''nihonto'') worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. ''Tachi'' and ''katana'' generally differ in length, degree of curvature, and how they were worn when sheathed, the latter depending on t ...

'' developed after ''kenukigata-tachi'', a structure in which the hilt is fixed to the tang

Tang or TANG most often refers to:

* Tang dynasty

* Tang (drink mix)

Tang or TANG may also refer to:

Chinese states and dynasties

* Jin (Chinese state) (11th century – 376 BC), a state during the Spring and Autumn period, called Tang (唐) b ...

(''nakago'') with a pin called ''mekugi'' was adopted. As a result, a sword with three basic external elements of Japanese swords, the cross-sectional shape of ''shinogi-zukuri'', a gently curved single-edged blade, and the structure of ''nakago'', was completed.''歴史人'' September 2020. pp.36–37.

In the Muromachi period

The is a division of Japanese history running from approximately 1336 to 1573. The period marks the governance of the Muromachi or Ashikaga shogunate (''Muromachi bakufu'' or ''Ashikaga bakufu''), which was officially established in 1338 by t ...

, battles were mostly fought on foot, and the samurai equipped with swords changed from the ''tachi'' to the light ''katana

A is a Japanese sword characterized by a curved, single-edged blade with a circular or squared guard and long grip to accommodate two hands. Developed later than the '' tachi'', it was used by samurai in feudal Japan and worn with the edge f ...

'' because many mobilized peasants were armed with spears and matchlock guns. In general, ''katana'' has a cross-sectional shape of shinogizukuri, similar to ''tachi'', but it is shorter than ''tachi'' and its blade curve is gentle.

''Wakizashi

The is one of the traditionally made Japanese swords (''nihontō'') worn by the samurai in feudal Japan.

History and use

The production of swords in Japan is divided into specific time periods:

'' and ''tantō

A is one of the traditionally made Japanese swords (Commons:Nihonto, ''nihonto'') that were worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. The tantō dates to the Heian period, when it was mainly used as a weapon but evolved in design over the year ...

'' are shorter swords than ''tachi'' and ''katana'', and these swords are often forged in the cross-sectional shape of ''hira-zukuri'' or ''kiriha-zukuri''.''歴史人'' September 2020. pp.47.

Heat treating

quenched

In materials science, quenching is the rapid cooling of a workpiece in water, oil, polymer, air, or other fluids to obtain certain material properties. A type of heat treating, quenching prevents undesired low-temperature processes, such as ph ...

in the conventional European fashion (i.e.: uniformly throughout the blade). Steel's exact flex and strength vary dramatically with heat treating

Heat treating (or heat treatment) is a group of industrial, thermal and metalworking processes used to alter the physical, and sometimes chemical, properties of a material. The most common application is metallurgical. Heat treatments are als ...

. If steel cools quickly it becomes martensite

Martensite is a very hard form of steel crystalline structure. It is named after German metallurgist Adolf Martens. By analogy the term can also refer to any crystal structure that is formed by diffusionless transformation.

Properties

M ...

, which is very hard but brittle. Slower and it becomes pearlite

Pearlite is a two-phased, lamellar (or layered) structure composed of alternating layers of ferrite (87.5 wt%) and cementite (12.5 wt%) that occurs in some steels and cast irons. During slow cooling of an iron-carbon alloy, pearlite form ...

, which bends easily and does not hold an edge. To maximize both the cutting edge and the resilience of the sword spine, a technique of differential heat-treatment is used. In this specific process, referred to as differential hardening or differential quenching, the sword is painted with layers of clay before heating, providing a thin layer or none at all on the edge of the sword, ensuring quick cooling to maximize the hardening for the edge. A thicker layer of clay is applied to the rest of the blade, causing slower cooling. This creates softer, more resilient steel, allowing the blade to absorb shock without breaking. This process is sometimes erroneously called differential tempering but this is actually an entirely different form of heat treatment.

To produce a difference in hardness, the steel is cooled at different rates by controlling the thickness of the insulating layer. By carefully controlling the heating and cooling speeds of different parts of the blade, Japanese swordsmiths were able to produce a blade that had a softer body and a hard edge.

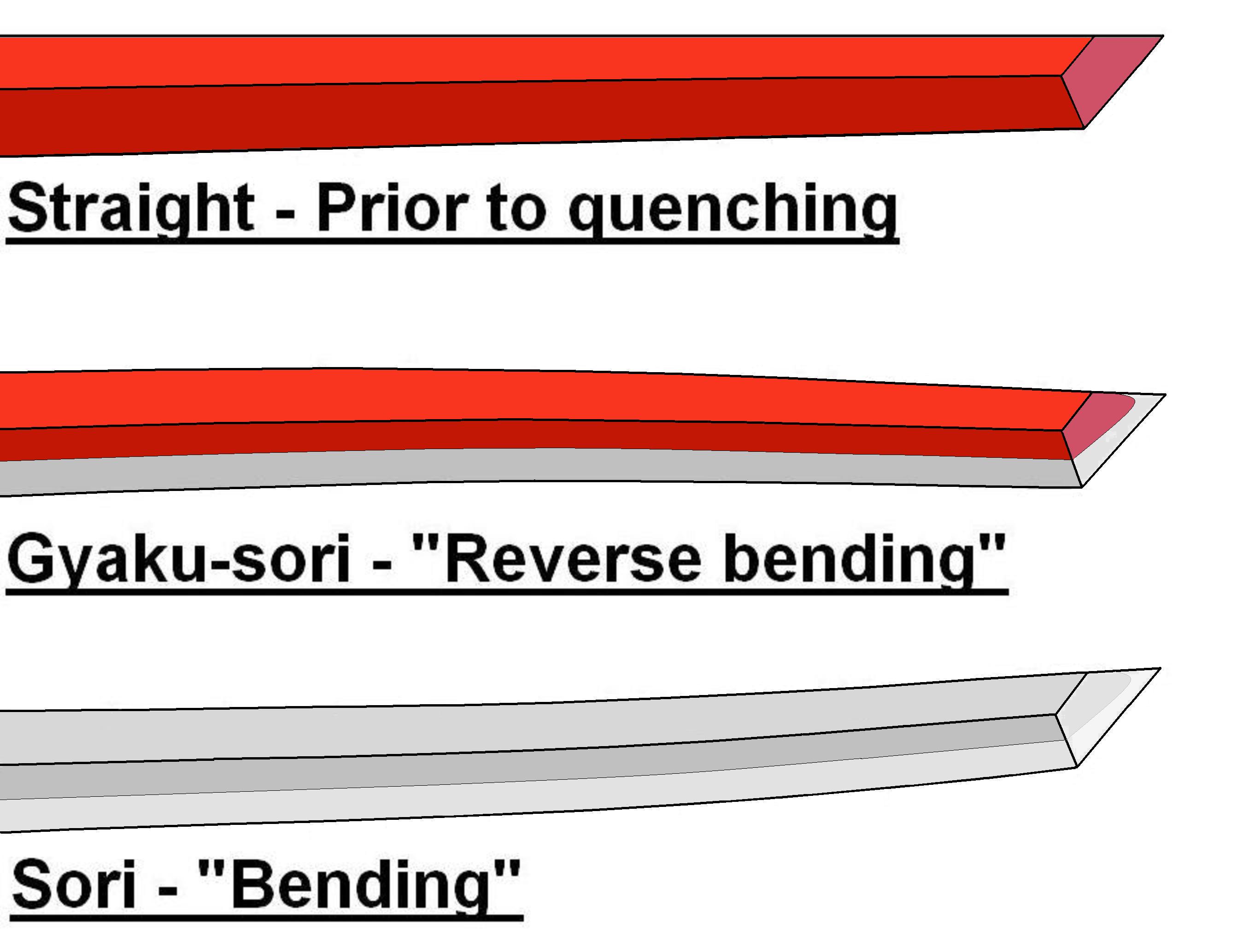

This process also has two side effects that have come to characterize Japanese swords: 1.) It causes the blade to curve and 2.) It produces a visible boundary between the hard and soft steel. When quenched, the uninsulated edge contracts, causing the sword to first bend towards the edge. However, the edge cannot contract fully before the martensite forms, because the rest of the sword remains hot and in a thermally expanded state. Because of the insulation, the sword spine remains hot and pliable for several seconds but then contracts much more than the edge, causing the sword to bend away from the edge, which aids the smith in establishing the curvature of the blade. Also, the differentiated hardness and the methods of polishing the steel can result in the '' hamon'' 刃紋 (frequently translated as "tempering line" but better translated as "hardening pattern"). The ''hamon'' is the visible outline of the ''yakiba'' (hardened portion) and is used as a factor to judge both the quality and beauty of the finished blade. The various hamon patterns result from the manner in which the clay is applied. They can also act as an indicator of the style of sword-making and sometimes as a signature for the individual smith. The differences in the hardenability of steels may be enhanced near the hamon, revealing layers or even different parts of the blade, such as the intersection between an edge made from edge-steel and sides made from skin-steel.''A History of Metallography'' By Cyril Smith -- The MIT Press 1960 Page 40--57

When quenching in water, carbon is rapidly removed from the surface of the steel, lowering its hardenability. To ensure the proper hardness of the cutting edge, help prevent cracking, and achieve the proper depth of the martensite, the sword is quenched prior to creating the bevel for the edge. If the thickness of the coating on the edge is balanced just right with the temperature of the water, the proper hardness can be produced without the need for tempering. However, in most cases, the edge will end up being too hard, so tempering the entire blade evenly for a short time is usually required to bring the hardness down to a more suitable point. The ideal hardness is usually between HRc58–60 on the Rockwell hardness

The Rockwell scale is a hardness scale based on indentation hardness of a material. The Rockwell test measures the depth of penetration of an indenter under a large load (major load) compared to the penetration made by a preload (minor load). Th ...

scale. Tempering is performed by heating the entire blade evenly to around , reducing the hardness in the martensite and turning it into a form of tempered martensite. The pearlite, on the other hand, does not respond to tempering and does not change in hardness. After the blade is heat treated, the smith would traditionally use a drawknife

A drawknife (drawing knife, draw shave, shaving knife) is a traditional woodworking hand tool used to shape wood by removing shavings. It consists of a blade with a handle at each end. The blade is much longer (along the cutting edge) than it is d ...

(''sen'') to bevel the edge and give the sword a rough shape before sending the blade to a specialist for sharpening and polishing. The polisher, in turn, determines the final geometry and curvature of the blade and makes any necessary adjustments.

Metallurgy

''Tamahagane'', as a raw material, is a highly impure metal. Formed in a bloomery process, the bloom ofsponge iron

Direct reduced iron (DRI), also called sponge iron, is produced from the direct reduction of iron ore (in the form of lumps, pellets, or fines) into iron by a reducing gas or elemental carbon produced from natural gas or coal. Many ores are suit ...

begins as an inhomogeneous mixture of wrought iron, steels, and pig iron. The pig iron contains more than 2% carbon. The high-carbon steel has about 1 to 1.5% carbon while the low-carbon iron contains about 0.2%. Steel that has a carbon content between the high and low carbon steel is called ''bu-kera'', which is often re-smelted with the pig iron to make ''saga-hagane'', containing roughly 0.7% carbon. Most of the intermediate-carbon steel, wrought iron and resmelted steel will be sold for making other items, like tools and knives, and only the best pieces of high-carbon steel, low-carbon iron, and pig iron are used for swordsmithing.

The various metals are also filled with slag, phosphorus and other impurities. Separation of the various metals from the bloom was traditionally performed by breaking it apart with small hammers dropped from a certain height, and then examining the fractures, in a process similar to the modern Charpy impact test

In materials science, the Charpy impact test, also known as the Charpy V-notch test, is a standardized high strain rate test which determines the amount of energy absorbed by a material during fracture. Absorbed energy is a measure of the mate ...

. The nature of the fractures are different for different types of steel. The high-carbon steel, in particular, contains pearlite, which produces a characteristic pearlescent-sheen on the crystals.

During the folding process, most of the impurities are removed from the steel, continuously refining the steel while forging. By the end of forging, the steel produced was among the purest steel alloys of the ancient world. Continuous heating causes the steel to decarburize, so a good quantity of carbon is either extracted from the steel as carbon dioxide or redistributed more evenly through diffusion

Diffusion is the net movement of anything (for example, atoms, ions, molecules, energy) generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemica ...

, leaving a nearly eutectoid composition (containing 0.77 to 0.8% carbon). The edge steel will generally end up with a composition that ranges from eutectoid to slightly hypoeutectoid (containing a carbon content under the eutectoid composition), giving enough hardenability without sacrificing ductility. The skin steel generally has slightly less carbon, often in the range of 0.5%. The core steel, however, remains nearly pure iron, responding very little to heat treatment. Cyril Stanley Smith

Cyril Stanley Smith (4 October 1903 – 25 August 1992) was a British metallurgist and historian of science. He is most famous for his work on the Manhattan Project where he was responsible for the production of fissionable metals. A graduate ...

, a professor of metallurgical history from Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

, performed an analysis of four different swords, each from a different century, determining the composition of the surface of the blades:''The Sword and the Crucible: A History of the metallurgy of European swords up to the 16th century'' by Alan Williams -- Brill 2012 page 42--43

In 1993, Jerzy Piaskowski performed an analysis of a ''katana'' of the type by cutting the sword in half and taking a cross section. The analysis revealed a carbon content ranging from 0.6 to 0.8% carbon at the surface and 0.2% at the core.

The steel in even the ancient swords may have sometimes come from whatever steel was available at the time. Because of its rarity in the ancient world, steel was usually recycled, so broken tools, nails and cookware often provided a supply of steel. Even steel looted from enemies in combat was valued for its use in swordsmithing.

According to Smith, the different layers of steel are made visible during the polishing because of one or both of two reasons: 1) the layers have a variation in carbon content, or 2) they have variation in the content of slag inclusions. When the variation is from slag inclusions by themselves, there will not be a noticeable effect near the ''hamon'', where the ''yakiba'' meets the ''hira''. Likewise, there will be no appreciable difference in the local hardness of the individual layers. A difference in slag inclusions generally appears as layers that are somewhat pitted while the adjacent layers are not. In one of the first metallurgical studies, Professor Kuni-ichi Tawara suggests that layers of high slag may have been added for practical as well as decorative reasons. Although slag has a weakening effect on the metal, layers of high slag may have been added to diffuse vibration and dampen recoil, allowing easier use without a significant loss in toughness.''A History of Metallography'' by Cyril Stanley Smith -- MIT Press 1960 Page 46--47

However, when the patterns occur from a difference in carbon content, there will be distinct indications of this near the ''hamon'', because the steel with higher hardenability will become martensite beyond the ''hamon'' while the adjacent layers will turn into pearlite. This leaves a distinct pattern of bright ''nioi'', which appear as bright streaks or lines that follow the layers a short distance away from the ''hamon'' and into the ''hira'', giving the ''hamon'' a wispy or misty appearance. The patterns were most likely revealed during the polishing operation by using a method similar to

According to Smith, the different layers of steel are made visible during the polishing because of one or both of two reasons: 1) the layers have a variation in carbon content, or 2) they have variation in the content of slag inclusions. When the variation is from slag inclusions by themselves, there will not be a noticeable effect near the ''hamon'', where the ''yakiba'' meets the ''hira''. Likewise, there will be no appreciable difference in the local hardness of the individual layers. A difference in slag inclusions generally appears as layers that are somewhat pitted while the adjacent layers are not. In one of the first metallurgical studies, Professor Kuni-ichi Tawara suggests that layers of high slag may have been added for practical as well as decorative reasons. Although slag has a weakening effect on the metal, layers of high slag may have been added to diffuse vibration and dampen recoil, allowing easier use without a significant loss in toughness.''A History of Metallography'' by Cyril Stanley Smith -- MIT Press 1960 Page 46--47

However, when the patterns occur from a difference in carbon content, there will be distinct indications of this near the ''hamon'', because the steel with higher hardenability will become martensite beyond the ''hamon'' while the adjacent layers will turn into pearlite. This leaves a distinct pattern of bright ''nioi'', which appear as bright streaks or lines that follow the layers a short distance away from the ''hamon'' and into the ''hira'', giving the ''hamon'' a wispy or misty appearance. The patterns were most likely revealed during the polishing operation by using a method similar to lapping

Lapping is a machining process in which two surfaces are rubbed together with an abrasive between them, by hand movement or using a machine.

Lapping often follows other subtractive processes with more aggressive material removal as a first ste ...

, without bringing the steel to a full polish, although sometimes chemical reactions with the polishing compounds may have also been used to provide a level of etching. The differences in hardness primarily appear as a difference in the microscopic scratches left on the surface. The harder metal produces shallower scratches, so it diffuses the reflected light, while the softer metal has deeper, longer scratches, appearing either shiny or dark depending on the viewing angle.

Metallography

Metallurgy did not arise as a science until the early 20th century. Before this,metallography

Metallography is the study of the physical structure and components of metals, by using microscopy.

Ceramic and polymeric materials may also be prepared using metallographic techniques, hence the terms ceramography, plastography and, collecti ...

was the primary method used for studying metals. Metallography is the study of the patterns in metals, the nature of fractures, and the microscopic crystal formations. However, neither metallography as a science nor the crystal theory of metals emerged until nearly a century after the invention of the microscope. The ancient swordsmiths had no knowledge of metallurgy, nor did they understand the relationship between carbon and iron. Everything was typically learned by a process of trial-and-error, apprenticeship, and, as sword-making technology was often a closely guarded secret, some espionage. Prior to the 14th century, very little attention was paid to the patterns in the blade as an aesthetic quality. However, the Japanese smiths often prided themselves on their understanding of the internal macro-structure of metals, including the layering, the wood grain

Wood grain is the longitudinal arrangement of wood fibers or the pattern resulting from such an arrangement.

Definition and meanings

R. Bruce Hoadley wrote that ''grain'' is a "confusingly versatile term" with numerous different uses, including ...

-like structure, and use of different steel in different parts of the blade.

In Japan, steel-making technology was imported from China, most likely through Korea. The crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron (cast iron), iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using charcoal or coal fires ...

used in the Chinese swords, called ''chi-kang'' (combined steel), was similar to pattern welding, and edges of it were often forge welded to a back of soft iron, or . In trying to copy the Chinese method, the ancient smiths paid much attention to the various properties of steel and worked to combine them to produce a composite steel with an internal macro-structure that would provide a similar combination of hardness and toughness. Like all trial-and-error, each swordsmith often attempted to produce an internal structure that was superior to swords of their predecessors, or even ones that were better than their own previous designs. The harder metals provided strength, like "bones" within the steel, whereas the softer metal provided ductility, allowing the swords to bend before breaking. In ancient times, the Japanese smiths would often display these inhomogeneities in the steel, especially on fittings like the guard or pommel, creating rough, natural surfaces by letting the steel rust or by pickling it in acid, making the internal structure part of the entire aesthetic of the weapon.

In later times, this effect was often imitated by partially mixing various metals like copper together with the steel, forming ''mokume'' (wood-eye) patterns, although this was unsuitable for the blade. After the 14th century, the Japanese technology had reached a pinnacle, and little more could be done to improve the mechanical properties even by modern standards, thus more attention began to be paid to the patterns in the blade as an aesthetic quality. From then on advancements progressed along an artistic path and swords became regarded for their beauty as much as their suitability as a weapon. Intentionally decorative forging techniques were often employed, such as hammering dents in certain locations or drawing out the steel with fullers, which served to create a ''mokume'' pattern when the sword was filed and polished into shape, or by intentionally forging in layers of high slag content. By the 17th century, decorative hardening methods were often being used to increase the beauty of the blade, by shaping the clay. Hamons with trees, flowers, pill boxes, or other shapes became common during this era. By the 19th century, the decorative hamons were often being combined with decorative folding techniques to create entire landscapes, often portraying specific islands or scenery, crashing waves in the ocean, and misty mountain peaks.

Decoration

Almost all blades are decorated, although not all blades are decorated on the visible part of the blade. Once the blade is cool and the mud is scraped off, the blade has designs and grooves cut into it. One of the most important markings on the sword is performed here: the file markings. These are cut into the

Almost all blades are decorated, although not all blades are decorated on the visible part of the blade. Once the blade is cool and the mud is scraped off, the blade has designs and grooves cut into it. One of the most important markings on the sword is performed here: the file markings. These are cut into the tang

Tang or TANG most often refers to:

* Tang dynasty

* Tang (drink mix)

Tang or TANG may also refer to:

Chinese states and dynasties

* Jin (Chinese state) (11th century – 376 BC), a state during the Spring and Autumn period, called Tang (唐) b ...

(''nakago''), or the hilt section of the blade, during shaping, where they will be covered by a ''tsuka'' or hilt later. The tang is never supposed to be cleaned: doing this can cut the value of the sword in half or more. The purpose is to show how well the blade steel ages. Different types of file markings are used, including horizontal, slanted, and checked, known as ''ichi-monji'', ''ko-sujikai'', ''sujikai,'' ''ō-sujikai'', ''katte-agari'', ''shinogi-kiri-sujikai'', ''taka-no-ha'', and ''gyaku-taka-no-ha''. A grid of marks, from raking the file diagonally both ways across the tang, is called ''higaki'', whereas specialized "full dress" file marks are called ''kesho-yasuri''. Lastly, if the blade is very old, it may have been shaved instead of filed. This is called . While ornamental, these file marks also serve the purpose of providing an uneven surface which bites well into the hilt which fits over it. It is this pressure fit for the most part that holds the hilt in place, while the ''mekugi'' pin serves as a secondary method and a safety.

Some other marks on the blade are aesthetic: signatures and dedications written in ''kanji

are the logographic Chinese characters taken from the Chinese family of scripts, Chinese script and used in the writing of Japanese language, Japanese. They were made a major part of the Japanese writing system during the time of Old Japanese ...

'' and engravings depicting gods, dragons, or other acceptable beings, called ''horimono''. Some are more practical. The so-called "blood groove" or fuller does not in actuality allow blood to flow more freely from cuts made with the sword but is to reduce the weight of the sword while keeping structural integrity and strength. Grooves come in wide (''bo-hi''), twin narrow (''futasuji-hi''), twin wide and narrow (''bo-hi ni tsure-hi''), short (''koshi-hi''), twin short (''gomabushi''), twin long with joined tips (''shobu-hi''), twin long with irregular breaks (''kuichigai-hi''), and halberd-style (''naginata-hi'').

Polishing

When the rough blade is completed, the swordsmith turns the blade over to a polisher () whose job is to refine the shape of a blade and improve its aesthetic value. The entire process takes considerable time, in some cases easily up to several weeks. Early polishers used three types of stone, whereas a modern polisher generally uses seven. The modern high level of polish was not normally done before around 1600, since greater emphasis was placed on function over form. The polishing process almost always takes longer than even crafting, and a good polish can greatly improve the beauty of a blade, while a bad one can ruin the best of blades. More importantly, inexperienced polishers can permanently ruin a blade by badly disrupting its geometry or wearing down too much steel, both of which effectively destroy the sword's monetary, historic, artistic, and functional value.Mountings

In Japanese, thescabbard

A scabbard is a sheath for holding a sword, knife, or other large blade. As well, rifles may be stored in a scabbard by horse riders. Military cavalry and cowboys had scabbards for their saddle ring carbine rifles and lever-action rifles on the ...

for a ''katana'' is referred to as a '' saya'', and the handguard piece, often intricately designed as an individual work of art—especially in later years of the Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was characte ...

—was called the ''tsuba''. Other aspects of the mountings (''koshirae

Japanese sword mountings are the various housings and associated fittings ('' tosogu'') that hold the blade of a Japanese sword when it is being worn or stored. refers to the ornate mountings of a Japanese sword (e.g. ''katana'') used when the ...

''), such as the '' menuki'' (decorative grip swells), '' habaki'' (blade collar and scabbard wedge), '' fuchi'' and ''kashira

Kashira (russian: Каши́ра) is a town and the administrative center of Kashirsky District in Moscow Oblast, Russia, located on the Oka River south of Moscow. Population:

History

It was first mentioned in 1356 as the village of Koshira ...

'' (handle collar and cap), '' kozuka'' (small utility knife handle), '' kogai'' (decorative skewer-like implement), ''saya'' lacquer, and '' tsuka-ito'' (professional handle wrap, also named ''emaki''), received similar levels of artistry.

After the blade is finished it is passed on to a mountings maker, or ''sayashi'' (literally "sheath maker" but referring to those who make fittings in general). Sword mountings vary in their exact nature depending on the era but consist of the same general idea, with the variation being in the components used and in the wrapping style. The obvious part of the hilt consists of a metal or wooden grip called a ''tsuka'', which can also be used to refer to the entire hilt. The hand guard, or ''tsuba'', on Japanese swords (except for certain 20th century sabers which emulate Western navies') is small and round, made of metal, and often very ornate. (See ''koshirae

Japanese sword mountings are the various housings and associated fittings ('' tosogu'') that hold the blade of a Japanese sword when it is being worn or stored. refers to the ornate mountings of a Japanese sword (e.g. ''katana'') used when the ...

.'')

There is a pommel at the base known as a ''kashira'', and there is often a decoration under the braided wrappings called a ''menuki''. A bamboo peg called a ''mekugi'' is slipped through the ''tsuka'' and through the tang of the blade, using the hole called a ''mekugi-ana'' ("peg hole") drilled in it. This anchors the blade securely into the hilt. To anchor the blade securely into the sheath it will soon have, the blade acquires a collar, or ''habaki'', which extends an inch or so past the hand guard and keeps the blade from rattling.

There are two types of sheaths, both of which require exacting work to create. One is the ''shirasaya

Japanese sword mountings are the various housings and associated fittings ('' tosogu'') that hold the blade of a Japanese sword when it is being worn or stored. refers to the ornate mountings of a Japanese sword (e.g. ''katana'') used when the ...

'', which is generally made of wood and considered the "resting" sheath, used as a storage sheath. The other sheath is the more decorative or battle-worthy sheath which is usually called either a ''jindachi-zukuri'', if suspended from the ''obi'' (belt) by straps (''tachi''-style), or a ''buke-zukuri'' sheath if thrust through the ''obi'' (katana-style). Other types of mounting include the ''kyū-guntō'', ''shin-guntō'', and ''kai-guntō'' types for the twentieth-century military.

Modern swordsmithing

Traditional swords are still made in Japan and occasionally elsewhere; they are termed "shinsakuto" or "shinken" (true sword), and can be very expensive. These are not considered reproductions as they are made by traditional techniques and from traditional materials. Swordsmiths in Japan are licensed; acquiring this license requires a long apprenticeship. Outside Japan there are a couple of smiths working by traditional or mostly traditional techniques, and occasional short courses taught in Japanese swordsmithing. A very large number of low-quality reproduction ''katana'' and ''wakizashi'' are available; their prices usually range between $10 to about $200. These cheap blades are Japanese in shape only—they are usually machine made and machine sharpened and minimally hardened or heat-treated. The hamon pattern (if any) on the blade is applied by scuffing, etching, or otherwise marking the surface, without any difference in hardness or temper of the edge. The metal used to make low-quality blades is mostly cheap stainless steel, and typically is much harder and more brittle than true katana. Finally, cheap reproduction Japanese swords usually have fancy designs on them since they are just for show. Better-quality reproduction katana typically range from $200 to about $1000 (though some can go easily above two thousand for quality production blades, folded and often traditionally constructed and with a proper polish), and high-quality or custom-made reproductions can go up to $15,000–$50,000. These blades are made to be used for cutting and are usually heat-treated. High-quality reproductions made from carbon steel will often have a differential hardness or temper similar to traditionally made swords, and will show a hamon; they will not show a hada (grain), since they are generally not made from folded steel. A wide range of steels are used in reproductions, ranging from carbon steels such as 1020, 1040, 1060, 1070, 1095, and 5160, stainless steels such as 400, 420, 440, to high-end specialty steels such as L6 and S7. Most cheap reproductions are made from inexpensive stainless steels such as 440A (often just termed "440").Sword Forum online magazine, March 1999 With a normal

Rockwell hardness

The Rockwell scale is a hardness scale based on indentation hardness of a material. The Rockwell test measures the depth of penetration of an indenter under a large load (major load) compared to the penetration made by a preload (minor load). Th ...

of 56 and up to 60, stainless steel is much harder than the back of a differentially hardened katana (HR50), and is therefore much more prone to breaking, especially when used to make long blades. Stainless steel is also much softer at the edge (a traditional katana is usually more than HR60 at the edge). Furthermore, cheap swords designed as wall-hanging or sword rack decorations often also have a "rat-tail" tang, which is a thin, usually threaded bolt of metal welded onto the blade at the hilt area. These are a major weak point and often break at the weld, resulting in a dangerous and unreliable sword.

Some modern swordsmiths have made high quality reproduction swords using the traditional method, including one Japanese swordsmith who began manufacturing swords in Thailand using traditional methods, and various American and Chinese manufacturers. These however will always be different from Japanese swords made in Japan, as it is illegal to export the ''tamahagane'' jewel steel as such without it having been made into value-added products first. Nevertheless, some manufacturers have made differentially tempered swords folded in the traditional method available for relatively little money (often one to three thousand dollars), and differentially tempered, non-folded steel swords for several hundred. Some practicing martial artists prefer modern swords, whether of this type or made in Japan by Japanese craftsmen, because many of them cater to martial arts demonstrations by designing "extra light" swords which can be maneuvered relatively faster for longer periods of time, or swords specifically designed to perform well at cutting practice targets, with thinner blades and either razor-like flat-ground or hollow ground edges.

Notable swordsmiths

*Amakuni

is the legendary swordsmith who supposedly created the first single-edged longsword (tachi) with curvature along the edge in the Yamato Province around 700 AD. He was the head of a group of swordsmiths employed by the Emperor of Japan to make we ...

legendary swordsmith who supposedly created the first single-edged longsword with curvature along the edge in the Yamato Province around 700 AD

*Akitsugu Amata

(also known as ) (born 1927 – July 5, 2013) was a Japanese swordsmith.

Amata followed his father Amata Sadayoshi into the trade of sword-making after the latter died in 1937, moving to Tokyo from his home in Niigata Prefecture in order to enrol ...

(1927–2013)

*Hikoshiro Sadamune

Hikoshirō Sadamune (相模國住人貞宗 - ''Sagami kuni junin Sadamune'') (born Einin 6, 1298; died Shōhei 4, 1349) also called Sōshū Sadamune was a swordsmith of the Japanese sword#Classification by school, Sōshū school, originally from ...

(1298–1349)

*Kanenobu

Kanenobu ��信, 兼延, 兼言is the name of both a Japanese swordsmith and his clan, a group that is famous for producing samurai swords, katana, wakizashi and, occasionally, spears in the style of the Mino School - Tōkaidō. The history of ...

(17th century)

* Kenzō Kotani (1909–2003)

*Masamune

, was a medieval Japanese blacksmith widely acclaimed as Japan's greatest swordsmith. He created swords and daggers, known in Japanese as ''tachi'' and ''tantō'', in the ''Sōshū'' school. However, many of his forged ''tachi'' were made into ...

(c. 1264 – 1343)

*Muramasa

, commonly known as , was a famous swordsmith who founded the Muramasa school and lived during the Muromachi period (14th to 16th centuries) in Kuwana, Ise Province, Japan (current Kuwana, Mie).Fukunaga, 1993. vol. 5, pp. 166–167.

In spite o ...

(16th century)

*Nagasone Kotetsu

(born Nagasone Okisato) was a Japanese swordmaker of the early Edo period. His father was an armorer who served Ishida Mitsunari, the lord of Sawayama. However, as Ishida was defeated by Tokugawa Ieyasu at the Battle of Sekigahara, the Nagaso ...

(c. 1597 – 1678)

* Okubo Kazuhira (1943–2003)

* Shintōgo Kunimitsu (13th century)

*Masamine Sumitani

was a Japanese swordsmith.

Sumitani's family ran a soy-sauce manufacturing business, but rather than entering the family trade, Masamine opted to study at Ritsumeikan University, with a view to becoming a swordsmith, graduating in 1941 with a de ...

(1921–1998)

See also

* Maraging steel for fencing blades - highly breakage resistant, very good for pointed weapons, not good for edgedReferences

External links

Construction of the Shinken in the Modern Age

Japanese Sword Polishing Techniques

Japanese Sword History

What is Tamahagane ?

Tamahagane – Unique Metal for Unique Japanese Swords

{{DEFAULTSORT:Japanese Swordsmithing

Smithing

A metalsmith or simply smith is a craftsperson fashioning useful items (for example, tools, kitchenware, tableware, jewelry, armor and weapons) out of various metals. Smithing is one of the oldest metalworking occupations. Shaping metal with a h ...

Samurai weapons and equipment