Jane Joseph on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jane Marian Joseph (31 May 1894 – 9 March 1929) was an English composer, arranger and music teacher. She was a pupil and later associate of the composer

In the autumn of 1913, at the age of 19, Joseph began studying

In the autumn of 1913, at the age of 19, Joseph began studying

Joseph increased her teaching commitments by often deputising for Holst, both at James Allen's and at SPGS. She also continued in her role of the composer's amanuensis, and was invited to attend the private premiere of ''The Planets'', on 29 September 1918 at the

Joseph increased her teaching commitments by often deputising for Holst, both at James Allen's and at SPGS. She also continued in her role of the composer's amanuensis, and was invited to attend the private premiere of ''The Planets'', on 29 September 1918 at the

In 1919, seeking to consolidate her musical career, Joseph joined the

In 1919, seeking to consolidate her musical career, Joseph joined the

In November 1921 Joseph organised the Morley forces to perform a large-scale pageant, celebrating the bicentenary of the church of

In November 1921 Joseph organised the Morley forces to perform a large-scale pageant, celebrating the bicentenary of the church of

Monthly Musical Record

', 1 April 1931, p98. Reprinted on the website

British Classical Music: The Land of Lost Content

' * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Joseph, Jane M. 1894 births 1929 deaths 20th-century classical composers British music educators British women classical composers English classical composers English Jews Jewish classical composers People educated at St Paul's Girls' School Alumni of Girton College, Cambridge Burials at Willesden Jewish Cemetery Deaths from kidney failure 20th-century English composers 20th-century English women musicians Women music educators 20th-century women composers

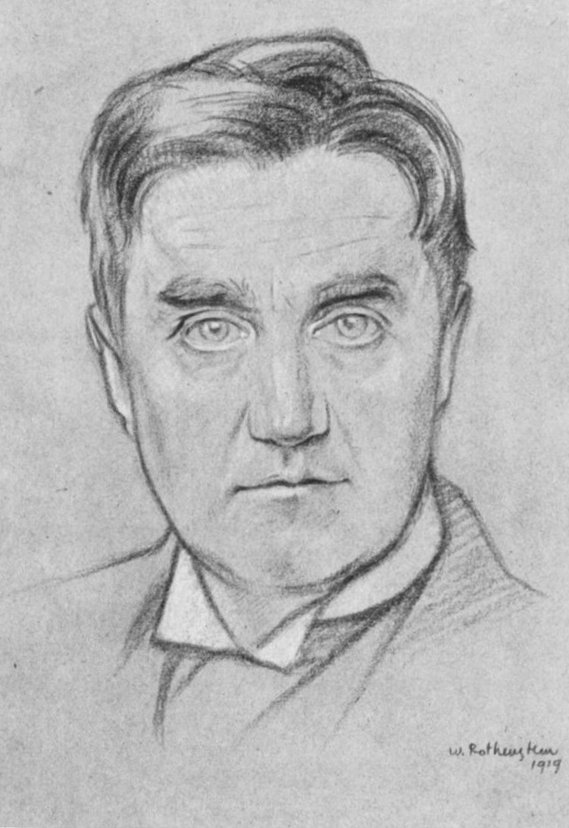

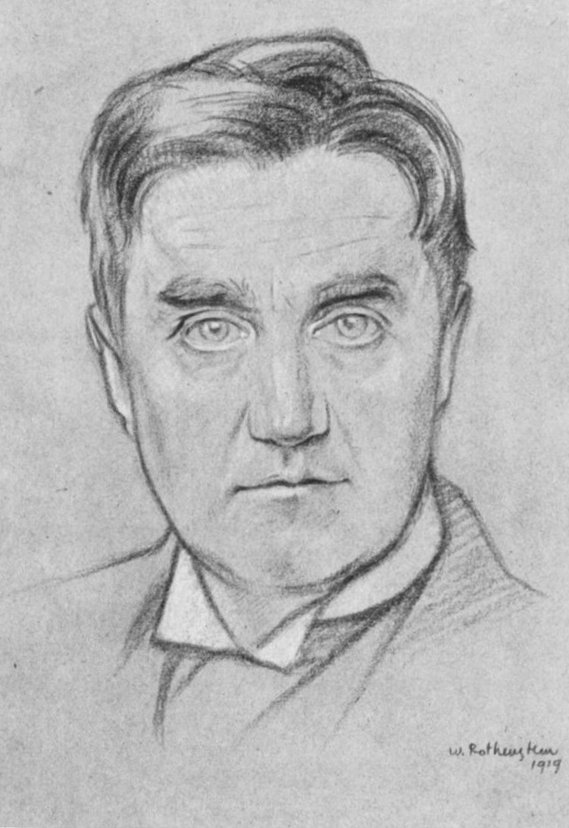

Gustav Holst

Gustav Theodore Holst (born Gustavus Theodore von Holst; 21 September 1874 – 25 May 1934) was an English composer, arranger and teacher. Best known for his orchestral suite ''The Planets'', he composed many other works across a range ...

, and was instrumental in the organisation and management of various of the music festivals which Holst sponsored. Many of her works were composed for performance at these festivals and similar occasions. Her early death at age 35, which prevented the full realisation of her talents, was considered by her contemporaries as a considerable loss to English music.

Holst first observed Joseph's potential when he was teaching her composition at St Paul's Girls' School

St Paul's Girls' School is an independent day school for girls, aged 11 to 18, located in Brook Green, Hammersmith, in West London, England.

History

St Paul's Girls' School was founded by the Worshipful Company of Mercers in 1904, using part o ...

. She began to act as his amanuensis

An amanuensis () is a person employed to write or type what another dictates or to copy what has been written by another, and also refers to a person who signs a document on behalf of another under the latter's authority. In one example Eric Fenby ...

in 1914, when he was composing ''The Planets

''The Planets'', Op. 32, is a seven- movement orchestral suite by the English composer Gustav Holst, written between 1914 and 1917. In the last movement the orchestra is joined by a wordless female chorus. Each movement of the suite is name ...

'', her special responsibility being the preparation of the score for the "Neptune" movement. She continued to assist Holst with transcriptions, arrangements and translations, and was his librettist for the choral ballet ''The Golden Goose''.

During her short professional life she became an active member of the Society of Women Musicians The Society of Women Musicians was a British group founded in 1911 for mutual cooperation between women composers and performers, in response to the limited professional opportunities for women musicians at the time. The founders included Katharine ...

, was the prime mover behind the first Kensington Musical Competition Festival, and helped to found the Kensington Choral Society. She also taught music at a girls' school, where Holst's daughter Imogen was one of her pupils, and became a leading figure in the musical life of Morley College

Morley College is a specialist adult education and further education college in London, England. The college has three main campuses, one in Waterloo on the South Bank, and two in West London namely in North Kensington and in Chelsea, the lat ...

. Two memorial prizes and scholarships were endowed in her name.

Most of Joseph's compositions were never published and are now considered lost. Of her published works, two early short orchestral pieces, ''Morris Dance'' and ''Bergamask'' won considerable critical praise, although neither became part of the general orchestral repertory. Two choral works, ''A Festival Venite'' and ''A Hymn for Whitsuntide'' were admired during her lifetime, but never commercially recorded. Since her death, her work has seldom been performed, but occasionally been broadcast. Her carol "A Little Childe There is Ibore" was thought by Holst to be among the best of its kind.

Biography

Family background and early childhood

Jane Joseph was born on 31 May 1894 at 23 Clanricarde Gardens, in theNotting Hill

Notting Hill is a district of West London, England, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Notting Hill is known for being a cosmopolitan and multicultural neighbourhood, hosting the annual Notting Hill Carnival and Portobello Road M ...

district of the Borough of Kensington, London, to a prosperous Jewish family. Her father, George Solomon Joseph (1844–1917), a solicitor

A solicitor is a legal practitioner who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally-defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and ...

in his family's firm, had married Henrietta, née Franklin (1861–1938) in 1880. Jane was their fourth child; the youngest of her three brothers was seven years older than her. George Joseph had a deep interest in music, which he passed on to his children; two sons, Frank (1881–1944) and Edwin (1887–1975), became competent string players, while Jane learned piano (she took her first examination at the age of seven) and later, double-bass. In time, Frank's musical children, with Jane and friends, formed the basis of a "Josephs orchestra" that performed concerts at Frank's home for many years.

St Paul's Girls' School and Gustav Holst

In 1909 Joseph won a scholarship toSt Paul's Girls' School

St Paul's Girls' School is an independent day school for girls, aged 11 to 18, located in Brook Green, Hammersmith, in West London, England.

History

St Paul's Girls' School was founded by the Worshipful Company of Mercers in 1904, using part o ...

(SPGS) in Hammersmith

Hammersmith is a district of West London, England, southwest of Charing Cross. It is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, and identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

...

.Gibbs 2000, p. 26 The school had opened in 1904, as an offshoot of the long-established St Paul's School for boys. Its high mistress, Frances Ralph Gray, was a formidable figure with traditional views about female education, who nevertheless provided a lively and varied learning environment in which Joseph excelled. Apart from her academic successes, Joseph played double-bass in the school orchestra, gave an acclaimed piano performance of Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard w ...

's D minor

D minor is a minor scale based on D, consisting of the pitches D, E, F, G, A, B, and C. Its key signature has one flat. Its relative major is F major and its parallel major is D major.

The D natural minor scale is:

Changes needed for t ...

keyboard concerto, began to compose, and won a prize for sight-reading

In music, sight-reading, also called ''a prima vista'' (Italian meaning "at first sight"), is the practice of reading and performing of a piece in a music notation that the performer has not seen or learned before. Sight-singing is used to descri ...

. While at the school she composed "The Carrion Crow", a song setting which, in 1914, became her first published work.Gibbs 2000, p. 28 Outside music she supported the school's Literary Society, where she presented papers on Charlotte Brontë

Charlotte Brontë (, commonly ; 21 April 1816 – 31 March 1855) was an English novelist and poet, the eldest of the three Brontë sisters who survived into adulthood and whose novels became classics of English literature.

She enlisted i ...

and Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poe ...

. She also won Honours in the examinations of the Royal Drawing Society

The Royal Drawing Society of Great Britain and Ireland was founded in 1888 in London, with the aim of teaching drawing for educational reasons.

The methods of instruction were based on the idea that very young children attempt to draw before the ...

.

Among the music teachers at SPGS, most significantly in terms of her musical development, Joseph encountered the emergent composer Gustav Holst

Gustav Theodore Holst (born Gustavus Theodore von Holst; 21 September 1874 – 25 May 1934) was an English composer, arranger and teacher. Best known for his orchestral suite ''The Planets'', he composed many other works across a range ...

, then little known, who taught her composition. After leaving the Royal College of Music

The Royal College of Music is a music school, conservatoire established by royal charter in 1882, located in South Kensington, London, UK. It offers training from the Undergraduate education, undergraduate to the Doctorate, doctoral level in a ...

in 1898 Holst had earned his living as an organist, and as a trombonist in various orchestras, while awaiting critical recognition as a composer. In 1903 he gave up his orchestral appointments to concentrate on composing, but found that he needed a regular income. He became a music teacher, initially at the James Allen's Girls' School

James Allen's Girls' School, abbreviated JAGS, is an independent day school situated in Dulwich, South London, England. It is the second oldest girls’ independent school in Great Britain - Godolphin School in Salisbury being the oldest, founded ...

in Dulwich

Dulwich (; ) is an area in south London, England. The settlement is mostly in the London Borough of Southwark, with parts in the London Borough of Lambeth, and consists of Dulwich Village, East Dulwich, West Dulwich, and the Southwark half of ...

; in 1905 he was recommended to Frances Gray by Adine O'Neill, a former pupil of Clara Schumann

Clara Josephine Schumann (; née Wieck; 13 September 1819 – 20 May 1896) was a German pianist, composer, and piano teacher. Regarded as one of the most distinguished pianists of the Romantic era, she exerted her influence over the course of a ...

, who taught piano at SPGS. He was first appointed on a part-time basis to teach singing, and later extended his activities to cover the school's wider music curriculum including conducting and composition. According to the composer Alan Gibbs, Joseph quickly came under Holst's spell, and adopted his principles as her own. Holst later described her as the best girl pupil he ever had: "From the first she showed an individual attitude of mind and an eagerness to absorb all that was beautiful".

Student, scribe and teacher, 1913–1918

Girton

In the autumn of 1913, at the age of 19, Joseph began studying

In the autumn of 1913, at the age of 19, Joseph began studying Classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

at Girton College, Cambridge

Girton College is one of the 31 constituent colleges of the University of Cambridge. The college was established in 1869 by Emily Davies and Barbara Bodichon as the first women's college in Cambridge. In 1948, it was granted full college status ...

.Gibbs 2000, p. 27 At that time, under Cambridge University regulations that were not fully repealed until 1948, women were ineligible to receive degrees, although they could sit the degree examinations, in Joseph's case the Classical Tripos

The Classical Tripos is the taught course in classics at the Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge. It is equivalent to Literae Humaniores at Oxford. It is traditionally a three-year degree, but for those who have not previously studied L ...

. She soon found much in the university's life to divert her from her regular studies: debating, drama and, above all, music. In her first term she became a double-bass player in the Cambridge University Musical Society

The Cambridge University Musical Society (CUMS) is a federation of the university's main orchestral and choral ensembles, which cumulatively put on a substantial concert season during the university term.

Background

Music has a long history at Cam ...

orchestra, under its conductor Cyril Rootham

Cyril Bradley Rootham (5 October 1875 – 18 March 1938) was an English composer, educator and organist. His work at Cambridge University made him an influential figure in English music life. A Fellow of St John's College, where he was also or ...

. She also sang alto

The musical term alto, meaning "high" in Italian (Latin: ''altus''), historically refers to the contrapuntal part higher than the tenor and its associated vocal range. In 4-part voice leading alto is the second-highest part, sung in choruses by ...

in the society's choir, and may have participated in a performance of Berlioz's ''La damnation de Faust

''La damnation de Faust'' (English: ''The Damnation of Faust''), Op. 24 is a work for four solo voices, full seven-part chorus, large children's chorus and orchestra by the French composer Hector Berlioz. He called it a "''légende dramatique'' ...

'' that was praised in the ''Cambridge Review'' of 17 June 1914. During vacations she continued her composition studies under Holst; in 1916 her "Wassail Song", a companion piece to "The Carrion Crow", was published. At Girton she wrote incidental music for a performance of W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

's verse play ''The Countess Cathleen

''The Countess Cathleen'' is a verse drama by William Butler Yeats in blank verse (with some lyrics). It was dedicated to Maud Gonne, the object of his affections for many years.

Editions and revisions

The play was first published in 1892 in ...

'', in which she acted the part of the First Dragon.

From 1915 Joseph's association with Holst became closer. Overextended by his teaching duties and other commitments, Holst required assistance in the task of organising his music for publication and performance, and used a group of young women volunteers—his "scribes"—to make fair copies of his scores, write out instrumental or vocal parts, or prepare piano arrangements. In 1915 the composer was working on his largest and best-known work, the orchestral suite ''The Planets

''The Planets'', Op. 32, is a seven- movement orchestral suite by the English composer Gustav Holst, written between 1914 and 1917. In the last movement the orchestra is joined by a wordless female chorus. Each movement of the suite is name ...

'', and invited Joseph, in her vacations, to join his scribes. Among these were Vally Lasker, a piano teacher from SPGS, and Nora Day, who had been a pupil with Joseph at the school and since 1913 had been teaching there. Joseph's main assignment for ''The Planets'' was to copy the "Neptune" movement, of which almost the entire original manuscript is written in her hand. For the rest of her career she remained one of Holst's most regular amanuenses

An amanuensis () is a person employed to write or type what another dictates or to copy what has been written by another, and also refers to a person who signs a document on behalf of another under the latter's authority. In one example Eric Fenby ...

, and he came to rely on her more than on any other. Her commitments to musical activities at Girton, combined with her work for Holst, had an adverse effect on her formal studies. In the 1916 Classical Tripos examinations she was awarded only a Class III pass, a disappointing result duly noted in her parting testimonial from the college.Gibbs 2000, pp. 29–30

Early career

When Joseph left Girton, theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

was at a critical state; the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme ( French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place bet ...

had begun on 1 July 1916. Joseph wanted to assist the war effort, and after considering work on the land or in a munitions factory, took up part-time welfare work in Islington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ar ...

. In the autumn of 1916 she began teaching at Eothen

Alexander William Kinglake (5 August 1809 – 2 January 1891) was an English travel writer and historian.

He was born near Taunton, Somerset, and educated at Eton College and Trinity College, Cambridge. He was called to the Bar in 1837, an ...

, a small private school for girls in Caterham

Caterham () is a town in the Tandridge District of Surrey, England. The town is administratively divided into two: Caterham on the Hill, and Caterham Valley, which includes the main town centre in the middle of a dry valley but rises to equal ...

, founded and run by the Misses Catharine and Winifred Pye. In 1917 Holst's ten-year-old daughter Imogen started at the school; soon, under Joseph's guidance the young pupil was composing her own music.Grogan (ed.), pp. 9–11 Joseph extended her own musical activities by joining the orchestra at Morley College

Morley College is a specialist adult education and further education college in London, England. The college has three main campuses, one in Waterloo on the South Bank, and two in West London namely in North Kensington and in Chelsea, the lat ...

, where Holst was the director of music and where her brother Edwin had played the cello before the war.Gibbs 2000, pp. 31–32 At first she played the double-bass, but later took French horn

The French horn (since the 1930s known simply as the horn in professional music circles) is a brass instrument made of tubing wrapped into a coil with a flared bell. The double horn in F/B (technically a variety of German horn) is the horn most ...

lessons, possibly from Adolph Borsdorf; later still, at very short notice, she taught herself the timpani

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionall ...

part for a summer concert. By 1918 she was a member of the Morley committee that on 9 March organised and produced an opera burlesque, ''English Opera as She is Wrote'', in which English, Italian, German, French and Russian opera styles were parodied in successive scenes. The performance was a great success and was repeated at several venues. It may have inspired Holst to use parody in his own opera, ''The Perfect Fool

''The Perfect Fool'' is an opera in one act with music and libretto by the English composer Gustav Holst. Holst composed the work over the period of 1918 to 1922. The opera received its premiere at the Covent Garden Theatre, London, on 14 May 192 ...

'', which he began composing in 1918.Gibbs 2000, pp. 34–35 In her spare time Joseph founded and ran a choir for Kensington nannies

A nanny is a person who provides child care. Typically, this care is given within the children's family setting. Throughout history, nannies were usually servants in large households and reported directly to the lady of the house. Today, modern ...

, which took part in local singing contests as the "Linden Singers".

Joseph increased her teaching commitments by often deputising for Holst, both at James Allen's and at SPGS. She also continued in her role of the composer's amanuensis, and was invited to attend the private premiere of ''The Planets'', on 29 September 1918 at the

Joseph increased her teaching commitments by often deputising for Holst, both at James Allen's and at SPGS. She also continued in her role of the composer's amanuensis, and was invited to attend the private premiere of ''The Planets'', on 29 September 1918 at the Queen's Hall

The Queen's Hall was a concert hall in Langham Place, London, opened in 1893. Designed by the architect Thomas Knightley, it had room for an audience of about 2,500 people. It became London's principal concert venue. From 1895 until 1941, it ...

, where Adrian Boult

Sir Adrian Cedric Boult, CH (; 8 April 1889 – 22 February 1983) was an English conductor. Brought up in a prosperous mercantile family, he followed musical studies in England and at Leipzig, Germany, with early conducting work in London ...

conducted the Queen's Hall orchestra. She later wrote: "From the moment of Mars ... to the last sound of Neptune, it was a big thing that will last all our lives, I think".Gibbs 2000, pp. 36–37 She was able to draw on her classical education at Girton when she helped to translate the apocryphal

Apocrypha are works, usually written, of unknown authorship or of doubtful origin. The word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to writings which were kept secret because they were the vehicles of esoteric knowledge considered ...

work '' The Acts of John'' from the original Greek, to provide the text for Holst's '' Hymn of Jesus'' (1917); for the same work she prepared a vocal score and an arrangement for piano, strings and organ. She and Holst combined to produce a women's voices version (two sopranos and an alto) of William Byrd

William Byrd (; 4 July 1623) was an English composer of late Renaissance music. Considered among the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he had a profound influence on composers both from his native England and those on the continent. He ...

's ''Mass for Three Voices'', and Joseph worked alone to produce an orchestral accompaniment for Samuel Wesley

Samuel Wesley (24 February 1766 – 11 October 1837) was an English organist and composer in the late Georgian period. Wesley was a contemporary of Mozart (1756–1791) and was called by some "the English Mozart".Kassler, Michael & Olleson, Phi ...

's ''Sing Aloud with Gladness''. This latter work was prepared for the 1917 Whitsun

Whitsun (also Whitsunday or Whit Sunday) is the name used in Britain, and other countries among Anglicans and Methodists, for the Christian High Holy Day of Pentecost. It is the seventh Sunday after Easter, which commemorates the descent of the Ho ...

musical festival, one of an annual series of such festivals that Holst masterminded, first at his home town of Thaxted

Thaxted is a town and civil parish in the Uttlesford district of north-west Essex, England. The town is in the valley of the River Chelmer, not far from its source in the nearby village of Debden, and is 97 metres (318 feet) above sea level (whe ...

, in later years at assorted venues including Dulwich

Dulwich (; ) is an area in south London, England. The settlement is mostly in the London Borough of Southwark, with parts in the London Borough of Lambeth, and consists of Dulwich Village, East Dulwich, West Dulwich, and the Southwark half of ...

, Chichester

Chichester () is a cathedral city and civil parish in West Sussex, England.OS Explorer map 120: Chichester, South Harting and Selsey Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton B2 edition. Publishing Date:2009. It is the only ci ...

and Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour.

...

. Joseph became a key figure in these festivals, as organiser, performer and composer. At Thaxted in 1918 two of her compositions were performed: ''Hymn'' for female voices (now lost), and an orchestral piece, ''Barbara Noel's Morris'', which Joseph wrote to mark her friendship with the daughter of Conrad Noel

Conrad le Despenser Roden Noel (12 July 1869 – 22 July 1942) was an English priest of the Church of England. Known as the 'Red Vicar' of Thaxted, he was a prominent Christian socialist.

Early life

Noel was born on 12 July 1869 in Royal Cottage, ...

, Thaxted's vicar.

The years 1917 and 1918 also brought personal sadness. On 22 October 1917 Joseph's father died from a heart attack. On 27 May the following year, just after the Whitsun festival, her brother William was killed in action on the western front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

*Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a majo ...

; in September, Edwin was severely wounded in the final Allied offensive of the war. In his monograph on Joseph's life and music, the composer Alan Gibbs writes that "there is no hint in Jane's letters of the effect these events had on her". Gibbs quotes Duff Cooper

Alfred Duff Cooper, 1st Viscount Norwich, (22 February 1890 – 1 January 1954), known as Duff Cooper, was a British Conservative Party politician and diplomat who was also a military and political historian.

First elected to Parliament in 192 ...

, who wrote of those times: "... if we wept—as weep we did—we wept in secret".

Teacher, facilitator and composer, 1918–1928

Postwar years

In 1919, seeking to consolidate her musical career, Joseph joined the

In 1919, seeking to consolidate her musical career, Joseph joined the Society of Women Musicians The Society of Women Musicians was a British group founded in 1911 for mutual cooperation between women composers and performers, in response to the limited professional opportunities for women musicians at the time. The founders included Katharine ...

(SWM), founded in 1911 by the violinist and musicologist Marion Scott and others to promote the interests of women in music.Gibbs 2000, p. 40 Scott was known to Joseph, having been leader

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets vi ...

of the Morley orchestra. Joseph became a member of the SWM's Composers' Sectional Committee, and occasionally gave lectures to the society on subjects such as "The Necessity of Practical Experience for Composers", and "The Composer as Pupil". In the summer of 1919 she took conducting lessons from Adrian Boult

Sir Adrian Cedric Boult, CH (; 8 April 1889 – 22 February 1983) was an English conductor. Brought up in a prosperous mercantile family, he followed musical studies in England and at Leipzig, Germany, with early conducting work in London ...

, whom she described as "the most chinless man I have ever met".Gibbs 2000, pp. 38–39 The purpose of the lessons was to enable her to conduct her orchestral work ''Bergamask'', which was performed at the Coliseum Theatre

The London Coliseum (also known as the Coliseum Theatre) is a theatre in St Martin's Lane, Westminster, built as one of London's largest and most luxurious "family" variety theatres. Opened on 24 December 1904 as the London Coliseum Theatre o ...

under a scheme devised by Sir Oswald Stoll

Sir Oswald Stoll (20 January 1866 – 9 January 1942) was an Australian-born British theatre manager and the co-founder of the Stoll Moss Group theatre company. He also owned Cricklewood Studios and film production company Stoll Pictures, wh ...

to showcase new British music. In that same summer she met Ralph Vaughan Williams

Ralph Vaughan Williams, (; 12 October 1872– 26 August 1958) was an English composer. His works include operas, ballets, chamber music, secular and religious vocal pieces and orchestral compositions including nine symphonies, written over ...

, a close friend of Holst. She played him some of her music, probably a piano reduction of ''Bergamask'', and described him as "a very appreciative critic".

Towards the end of 1918 Holst had asked Joseph to provide a libretto for his opera ''The Perfect Fool'', feeling that she might possess the required light touch that he thought his own writing lacked. It is not clear whether she declined, or whether Holst changed his mind, but he eventually wrote the text himself. Joseph did, however, write the story for a ballet based on Holst's music ''The Sneezing Charm''; the ballet, entitled ''A Magic Hour'', was performed at Morley in October 1920. Meantime, Joseph's works were being performed at SWM concerts: two songs, probably from her ''Mirage'' cycle, in January 1920, and some of her settings of Walter de la Mare

Walter John de la Mare (; 25 April 1873 – 22 June 1956) was an English poet, short story writer, and novelist. He is probably best remembered for his works for children, for his poem "The Listeners", and for a highly acclaimed selection of ...

poems in December.

At Eothen, Joseph continued to supervise Imogen Holst's musical education, aspects of which had earlier been causing Holst some concern. In a letter to his wife dated February 1919, written when he was serving as YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

musical organiser for British troops stationed in the Eastern Mediterranean, Holst reported that "I've had a very kind and wise letter from Jane about Imogen". Whatever issues had troubled Holst were resolved satisfactorily, and Joseph became Imogen's theory teacher: "Theory with Jane is ''ripping''", the young pupil enthused. In the summer term of 1920, with help from Joseph, Imogen devised and composed a "Dance of Nymphs and Shepherds" which was performed at the school on 9 July. At the beginning of 1921 Imogen started at SPGS; before becoming a boarder at Bute House (one of the school's residences for pupils), she stayed in the Joseph family home.

The Whitsun festivals, suspended during Holst's absence, resumed at Dulwich in 1920. Joseph's part in this event is unrecorded, but she made a major contribution to the following year's festivities, which began beside the Thames at Isleworth

Isleworth ( ) is a town located within the London Borough of Hounslow in West London, England. It lies immediately east of the town of Hounslow and west of the River Thames and its tributary the River Crane, London, River Crane. Isleworth's or ...

and concluded on Whit Monday at SPGS in the gardens of Bute House. For the Monday's celebrations Joseph devised a presentation of Purcell

Henry Purcell (, rare: September 1659 – 21 November 1695) was an English composer.

Purcell's style of Baroque music was uniquely English, although it incorporated Italian and French elements. Generally considered among the greatest En ...

's semi-opera

The terms "semi-opera", "dramatic opera" and "English opera" were all applied to Restoration entertainments that combined spoken plays with masque-like episodes employing singing and dancing characters. They usually included machines in the manne ...

from 1690, ''Dioclesian

''Dioclesian'' (''The Prophetess: or, The History of Dioclesian'') is an English tragicomic semi-opera in five acts by Henry Purcell to a libretto by Thomas Betterton based on the play '' The Prophetess'', by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger, w ...

''. Writing of the occasion after Joseph's death, Holst recalled that she had woven Purcell's music and Thomas Betterton

Thomas Patrick Betterton (August 1635 – 28 April 1710), the leading male actor and theatre manager during Restoration England, son of an under-cook to King Charles I, was born in London.

Apprentice and actor

Betterton was born in August 16 ...

's text, both long neglected, "into a delightful out-door pageant founded on a fairy story, complete with lost princess, dragon and princely hero". Not satisfied with planning every aspect of the outdoor performance, Joseph prepared an indoors version of the entertainment, should the weather require this. The production was a great success, and was repeated that summer in Hyde Park

Hyde Park may refer to:

Places

England

* Hyde Park, London, a Royal Park in Central London

* Hyde Park, Leeds, an inner-city area of north-west Leeds

* Hyde Park, Sheffield, district of Sheffield

* Hyde Park, in Hyde, Greater Manchester

Austra ...

and, in October 1921, at the Old Vic

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

*Old, Baranya, Hungary

* Old, Northamptonshire, England

*Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, Ma ...

theatre. Throughout this considerable organisational task, Holst wrote, "Jane gave the minimum of worry to each person concerned by giving herself the maximum of hard work and forethought".

Career zenith

In November 1921 Joseph organised the Morley forces to perform a large-scale pageant, celebrating the bicentenary of the church of

In November 1921 Joseph organised the Morley forces to perform a large-scale pageant, celebrating the bicentenary of the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. It is dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. There has been a church on the site since at least the mediev ...

. The text was by Laurence Housman

Laurence Housman (; 18 July 1865 – 20 February 1959) was an English playwright, writer and illustrator whose career stretched from the 1890s to the 1950s. He studied art in London. He was a younger brother of the poet A. E. Housman and his s ...

and the music, directed by Holst, was taken from the Morley repertory. In the following year Joseph's increasing recognition as a composer was confirmed when her ''Seven Two-Part Songs'' were performed at a SWM concert that included works by Ethel Smyth

Dame Ethel Mary Smyth (; 22 April 18588 May 1944) was an English composer and a member of the women's suffrage movement. Her compositions include songs, works for piano, chamber music, orchestral works, choral works and operas.

Smyth tended t ...

and other women composers.Gibbs 2000, p. 41 Two of Joseph's works, ''A Hymn for Whitsuntide'' and ''A Festival Venite'' were introduced during the 1922 Whitsun festival at All Saints' church, Blackheath Blackheath may refer to:

Places England

*Blackheath, London, England

** Blackheath railway station

**Hundred of Blackheath, Kent, an ancient hundred in the north west of the county of Kent, England

*Blackheath, Surrey, England

** Hundred of Blackh ...

, with Holst conducting. After the ''Venite'' premiere Joseph wrote appreciatively to Holst: "Do you suppose for one moment that any other conductor takes trouble like that? If you do, you are quite wrong". The ''Venite'' was performed on 13 June 1923 at the Queen's Hall

The Queen's Hall was a concert hall in Langham Place, London, opened in 1893. Designed by the architect Thomas Knightley, it had room for an audience of about 2,500 people. It became London's principal concert venue. From 1895 until 1941, it ...

, by the Philharmonic Choir under Charles Kennedy Scott

Charles James Kennedy Osborne Scott (16 November 18762 July 1965) was an English organist and choral conductor who played an important part in developing the performance of choral and polyphonic music in England, especially of early and modern En ...

; the ''Spectator

''Spectator'' or ''The Spectator'' may refer to:

*Spectator sport, a sport that is characterized by the presence of spectators, or watchers, at its matches

*Audience

Publications Canada

* ''The Hamilton Spectator'', a Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, ...

''s critic thought it a "very notable addition to modern British music". Amidst her compositional and other activities, Joseph found time, in 1922, to organise the first Kensington Musical Competition Festival, and to orchestrate many of the competition songs. In due course this festival became an important annual event in Kensington; Vaughan Williams was among the adjudicators. On 12 October 1922, Vaughan Williams's 50th birthday, Joseph organised a choir which gave an early-morning surprise performance in the composer's garden of a song she had written to mark the occasion.

As early as 1919, Joseph had written to her brother Edwin expressing concern about Holst's health.Gibbs 2000, p. 45 When following a physical breakdown in 1923 Holst gave up his duties at Morley College, Joseph wrote him a supportive letter congratulating him on his decision which would enable him to concentrate on composition. The following years were particularly fruitful for Holst, and Joseph assisted in many of the works he produced in the 1924–28 period. She helped him prepare the score for his ''Choral Symphony'', for which assistance he presented her with his original draft sketches, as a gesture of gratitude. Together with Lasker and Day she worked to prepare vocal and full scores for the opera ''At the Boar's Head

''At the Boar's Head'' is an opera in one act by the English composer Gustav Holst, his op. 42. Holst himself described the work as "A Musical Interlude in One Act". The libretto, by the composer himself, is based on Shakespeare's '' Henry IV, ...

'', and attended the rehearsals in March 1925. After the opera's premiere on 3 April she wrote to Holst with mildly critical comments on some of the singers, though with praise for the conductor, the young Malcolm Sargent

Sir Harold Malcolm Watts Sargent (29 April 1895 – 3 October 1967) was an English conductor, organist and composer widely regarded as Britain's leading conductor of choral works. The musical ensembles with which he was associated include ...

. When Holst composed a short choral piece to celebrate the 21st birthday of the Oriana Madrigal Society, Joseph provided words which humorously reflected the conductor Kennedy Scott's working methods; the work was greatly appreciated by the choir. In that same year, 1925, she helped to found the Kensington Choral Society. By this time the Joseph home in Kensington, where Jane lived for her whole life, was becoming a recognised musical gathering-place; a visitor recalled meeting Vaughan Williams, Boult, and the harpist Sidonie Goossens

Annie Sidonie Goossens OBE (19 October 1899 – 15 December 2004) was one of Britain's most enduring harpists. She made her professional debut in 1921, was a founder member of the BBC Symphony Orchestra and went on to play for more than half ...

there, among others.

In 1926 Joseph provided Holst with the libretto for his choral ballet ''The Golden Goose'', based on a story by the Brothers Grimm

The Brothers Grimm ( or ), Jacob (1785–1863) and Wilhelm (1786–1859), were a brother duo of German academics, philologists, cultural researchers, lexicographers, and authors who together collected and published folklore. They are among the ...

, and arranged its first performance at the 1926 Whitsun festival, held at the James Allen school.Gibbs 2000, pp. 48–49 Joseph also assisted Holst and the librettist Steuart Wilson

Sir James Steuart Wilson (21 July 1889 – 18 December 1966) was an English singer, known for tenor roles in oratorios and concerts in the first half of the 20th century. After the Second World War he was an administrator for several organ ...

in the production of a second choral ballet, ''The Morning of the Year''—the first work commissioned by the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

's newly formed music department—which was performed at the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

in March 1927. The Morley College Annual Report of 1927 recorded the formation of a folk dance club, and noted Joseph's "skilful direction" of the group. Her increasing interest in dance led her, that year, to join the English Folk Dance Society and the Kensington Dance Club.

Illness, death and tributes

The main feature of the 1928 Whitsun festival, held atCanterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour.

...

, was a religious drama, ''The Coming of Christ'', commissioned by George Bell George Bell may refer to:

Law and politics

* George Joseph Bell (1770–1843), Scottish jurist and legal author

* George Alexander Bell (1856–1927), Canadian pioneer and Saskatchewan politician

* George Bell (Canadian politician) (1869–1940) ...

, then Dean of Canterbury

The Dean of Canterbury is the head of the Chapter of the Cathedral of Christ Church, Canterbury, England. The current office of Dean originated after the English Reformation, although Deans had also existed before this time; its immediate precur ...

, and written by John Masefield

John Edward Masefield (; 1 June 1878 – 12 May 1967) was an English poet and writer, and Poet Laureate from 1930 until 1967. Among his best known works are the children's novels ''The Midnight Folk'' and ''The Box of Delights'', and the poem ...

. Holst provided the incidental music. In a photograph described by Gibbs, taken of the festival's organisers and performers, Joseph is sitting between Holst and Mrs Bell, "taller than either, an efficient-looking lady in her early thirties, clearly of some importance to the festival". This was Joseph's last Whitsun. Towards the end of the year her health began to fail; there is a mention in Holst's diary for 29 November 1928, "Jane's concert 8.15", but no indication is given of whether she was a performer. In February 1929 she paid off the final amount owing to the piano manufacturer C. Bechstein

C. Bechstein Pianoforte AG (also known as Bechstein, ) is a German manufacturer of pianos, established in 1853 by Carl Bechstein.

History

Before Bechstein

Young Carl Bechstein studied and worked in France and England as a piano craftsman, be ...

, for Morley's new piano for which she had been fundraising since 1926. On 9 March 1929 Joseph died at home, in Kensington, of kidney failure. After a private funeral she was buried in Willesden Jewish Cemetery

The Willesden United Synagogue Cemetery, usually known as Willesden Jewish Cemetery, is a Jewish cemetery at Beaconsfield Road, Willesden, in the London Borough of Brent, England. It opened in 1873 on a site. It has been described as the "R ...

.Gibbs 2000, pp. 50–51

Holst was in Venice when the news of Joseph's death reached him; although Imogen records that he received it stoically, he was privately devastated. Joseph had, wrote Imogen, "come nearest to his ideal of clear thinking and clear feeling". In his own tribute, Holst drew attention to Joseph's "infinite capacity for taking pains which amounts to genius". No Whitsun festival was held in 1929, but in early July, at an open-air production of Holst's ''The Golden Goose'' at Warwick Castle

Warwick Castle is a medieval castle developed from a wooden fort, originally built by William the Conqueror during 1068. Warwick is the county town of Warwickshire, England, situated on a meander of the River Avon. The original wooden motte-an ...

, a special performance of his ''St Paul's Suite'' was played in Joseph's memory. On 5 December 1929, at a competitive music festival, Vaughan Williams conducted the choir in Joseph's ''Hymn for Whitsuntide'' while the audience stood in tribute. The same hymn was played at the first resumed Whitsun festival, at Chichester

Chichester () is a cathedral city and civil parish in West Sussex, England.OS Explorer map 120: Chichester, South Harting and Selsey Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton B2 edition. Publishing Date:2009. It is the only ci ...

in May 1930. In July 1931 Holst included her music in a concert that he conducted at Chichester Cathedral

Chichester Cathedral, formally known as the Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity, is the seat of the Anglican Bishop of Chichester. It is located in Chichester, in West Sussex, England. It was founded as a cathedral in 1075, when the seat of the ...

, alongside works by William Byrd

William Byrd (; 4 July 1623) was an English composer of late Renaissance music. Considered among the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he had a profound influence on composers both from his native England and those on the continent. He ...

, Thomas Weelkes

Thomas Weelkes (baptised 25 October 1576 – 30 November 1623) was an English composer and organist. He became organist of Winchester College in 1598, moving to Chichester Cathedral. His works are chiefly vocal, and include madrigals, anthe ...

and Vaughan Williams. Over the course of the next few years Joseph's works were played at concerts and events organised by Morley College, the SWM, SPGS and the English Folk Dance Society. At Eothen a "Jane Joseph Memorial Prize" was established, and music scholarships were endowed in her name at Eothen and SPGS.

A friend who expressed personal sadness on hearing of Joseph's death revealed another aspect of her character: "England won't be the same without Jane. She was terribly difficult to get to know at all, and awfully lonely, I thought, in spite of all her friends—don't you think so?—but I can't imagine Music without her".

Music

Much of Joseph's music was written for performances at modest-scale events by amateur performers. As such it was never published, and over the years many works have been lost. The published works and the few others that survive, Gibbs believes, place Joseph in the category of "progressive" English composers.Gibbs 2000, pp. 53–54 Although her first few compositions were mainly songs, she demonstrated early abilities as an orchestral composer. Gibbs finds in her two short pieces, ''Morris Dance'' (1917) (originally ''Barbara Noel's Morris'') and ''Bergamask'' (1919), three and five minutes respectively, a "fine feeling for orchestral sound". The ''Morris Dance'' has added sparkle from aglockenspiel

The glockenspiel ( or , : bells and : set) or bells is a percussion instrument consisting of pitched aluminum or steel bars arranged in a keyboard layout. This makes the glockenspiel a type of metallophone, similar to the vibraphone.

The glo ...

, while ''Bergamask'' has a festive Italianate feel. The music writer Philip Scowcroft praises Joseph's confident handling of the sizeable orchestral forces required for the ''Morris Dance'', while the composer Havergal Brian

Havergal Brian (born William Brian; 29 January 187628 November 1972) was an English composer. He is best known for having composed 32 symphonies (an unusually high total for a 20th-century composer), most of them late in his life. His best-know ...

, Holst's contemporary, found ''Bergamask'' "exhilarating" and "full of promise". Gibbs suggests that these two works presage Holst's late choral ballets, and comments: "That these carefree pieces did not find a permanent place in the repertory is unfortunate".

In Joseph's ''Mirage'' song cycle of 1921 (five songs with string quartet accompaniment), a Holstian influence is evident alongside her own distinctive compositional voice. Gibbs highlights the first in the cycle, "Song", which initially echoes "To Varuna" from Holst's ''Rig Veda'' hymns, but evolves into "a different creation, distinguished by its own uncluttered quartet writing in which the viola has a special part to play". The final song, "Echo", has as much in common with Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped with ...

as with Holst. Joseph's ''Festival Venite'' from 1922 is an example of her use of the Modern Dorian mode (an ascending scale from D to the next D on the white piano keys), which became a feature of some of her later works. Scowcroft and Gibbs both point to Tudor influences in the ''Venite'' in which also, says Gibbs, "the congenial influence of Vaughan Williams in melody and harmony is felt".Gibbs 2000, p. 55 The orchestral score for this work lost, but an organ accompaniment has been devised. Joseph's unaccompanied choral ''Hymn for Whitsuntide'' also uses the Dorian Mode in what Holst described as a "flawless little motet"; this was first work of Joseph's to be broadcast, in 1968. A ''Short String Quartet'' in A minor was performed by the Winifred Smith Quartet in December 1922 and was accepted for publication by J.B. Cramer and Co. However, it was not published, and subsequently disappeared.Gibbs 2000, p. 56

Joseph's carol "A Little Childe There is Ibore", is a setting of a 15th-century poem for three female voices and piano or strings. Holst considered this "the best of Jane's many carols, and perhaps the hardest to perform well." Written in alternate bars of five and seven beats, it was praised by Brian for its originality. It was eventually broadcast by the BBC on 21 December 1995. Brian was also an admirer of Joseph's many instructional piano pieces: "pleasingly simple and unaffected". These were published between 1920 and 1925; Gibbs writes that these pieces "focus on technical aspects in tuneful and often modal contexts", with occasional excursions into other forms such as chaconne

A chaconne (; ; es, chacona, links=no; it, ciaccona, links=no, ; earlier English: ''chacony'') is a type of musical composition often used as a vehicle for variation on a repeated short harmonic progression, often involving a fairly short rep ...

and rondo

The rondo is an instrumental musical form introduced in the Classical period.

Etymology

The English word ''rondo'' comes from the Italian form of the French ''rondeau'', which means "a little round".

Despite the common etymological root, rondo ...

.

Notes and references

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * Holst, Gustav (1931). "Jane Joseph: An Appreciation".Monthly Musical Record

', 1 April 1931, p98. Reprinted on the website

British Classical Music: The Land of Lost Content

' * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Joseph, Jane M. 1894 births 1929 deaths 20th-century classical composers British music educators British women classical composers English classical composers English Jews Jewish classical composers People educated at St Paul's Girls' School Alumni of Girton College, Cambridge Burials at Willesden Jewish Cemetery Deaths from kidney failure 20th-century English composers 20th-century English women musicians Women music educators 20th-century women composers