Jane Ingham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rose Marie "Jane" Ingham ( ; 15 August 189710 September 1982) was an English botanist and scientific translator. She was appointed research assistant to

Ingham's father was the son of the Reverend Tupper Carey and Helen Jane, néeSandeman. He was educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, and trained at Cuddesdon Theological College. He was curate of Leeds before being appointed rector of St Margaret's Church, Lowestoft. In 1910, he was appointed canon residentiary of

Ingham's father was the son of the Reverend Tupper Carey and Helen Jane, néeSandeman. He was educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, and trained at Cuddesdon Theological College. He was curate of Leeds before being appointed rector of St Margaret's Church, Lowestoft. In 1910, he was appointed canon residentiary of

Ingham was educated at Claire House School, an all girl school in North Parade, Lowestoft, which specialised in the teaching of French. At the age of ten, she gained a prize in preliminary French examinations that were organised by the National Society of French Professors in England. She competed against candidates from the "best girls' schools in England", the written tests consisting of translation and composition (prose and poetry), essay, and questions on 17th to 19thcentury French literature. In the same year, she performed as ''Philaminte'' in the school's production of three scenes from

Ingham was educated at Claire House School, an all girl school in North Parade, Lowestoft, which specialised in the teaching of French. At the age of ten, she gained a prize in preliminary French examinations that were organised by the National Society of French Professors in England. She competed against candidates from the "best girls' schools in England", the written tests consisting of translation and composition (prose and poetry), essay, and questions on 17th to 19thcentury French literature. In the same year, she performed as ''Philaminte'' in the school's production of three scenes from

In January 1922, Ingham was appointed a research assistant in the botany department, where

In January 1922, Ingham was appointed a research assistant in the botany department, where

In the late 1920s, Ingham joined the Leeds University Amateurs, the university's

In the late 1920s, Ingham joined the Leeds University Amateurs, the university's

The Inghams owned a punt, called ''Pete'', moored in the River Cam, and it was used regularly during the summer for trips and picnics. They also went on many trips abroad, including India, and walking holidays in the

The Inghams owned a punt, called ''Pete'', moored in the River Cam, and it was used regularly during the summer for trips and picnics. They also went on many trips abroad, including India, and walking holidays in the

They concluded that the meristematic cells had walls containing a proteinpectin complex, that is, these walls "...commencing as interfaces in a proteincontaining medium may be regarded as composed at first mainly of protein." Florence Mary Wood, a British

They concluded that the meristematic cells had walls containing a proteinpectin complex, that is, these walls "...commencing as interfaces in a proteincontaining medium may be regarded as composed at first mainly of protein." Florence Mary Wood, a British

In Ingham's last study in the botany department at the University of Leeds, she

In Ingham's last study in the botany department at the University of Leeds, she

Portrait

of Ingham by William Roberts, circa 1922, "An English Cubist".

Afterimages: Photographs as an External Autobiographical Memory System and a Contemporary Art Practice

University of the Arts London Research Online. Photographs of Jane Ingham, taken by Albert Ingham, for Mark Ingham's PhD thesis at

Works by Ingham

at

Lorna Scott and her Mortar Board

by Margaret Stewart, for Egham Museum, on botanist Lorna Iris Scott, Joseph Hubert Priestley's collaborator after Ingham left for Cambridge. {{DEFAULTSORT:Ingham, Jane 1897 births 1982 deaths 20th-century British botanists 20th-century British women scientists 20th-century English people 20th-century English women Academics of the University of Leeds Alumni of the University of Leeds British translators British women botanists English botanists German–English translators People from Cambridge People from Leeds Women botanists

Joseph Hubert Priestley

Joseph Hubert Priestley (; 5 October 188331 October 1944) was a British lecturer in botany at University College, Bristol, and professor of botany and pro-vice-chancellor at the University of Leeds. He has been described as a gifted teacher w ...

in the Botany Department at the University of Leeds

, mottoeng = And knowledge will be increased

, established = 1831 – Leeds School of Medicine1874 – Yorkshire College of Science1884 - Yorkshire College1887 – affiliated to the federal Victoria University1904 – University of Leeds

, ...

, and together, they were the first to separate cell walls from the root tip of broad beans

''Vicia faba'', commonly known as the broad bean, fava bean, or faba bean, is a species of vetch, a flowering plant in the pea and bean family Fabaceae. It is widely cultivated as a crop for human consumption, and also as a cover crop. Var ...

. They analysed these cell walls and concluded that they contained protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

. She carried out experiments on the cork layer of trees to study how cells function under a change of orientation and found profound differences in cell division and elongation in the epidermal layer of plants.

At Leeds, Ingham was appointed subwarden of Weetwood Hall, and honorary secretary of the BritishItalian League. In 1930, she joined the Imperial Bureau of Plant and Crop Genetics at the School of Agriculture in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

, England, as a scientific officer and translator. The bureau was responsible for publishing a series of abstract journals on various aspects of crop breeding and genetics. In 1932, she married Albert Ingham

Albert Edward Ingham (3 April 1900 – 6 September 1967) was an English mathematician.

Early life and education

Ingham was born in Northampton. He went to Stafford Grammar School and began his studies at Trinity College, Cambridge in January ...

, then a fellow and director of studies at King's College, Cambridge. Ingham spent the war years in Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton is a municipality with a borough form of government in Mercer County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton and Princeton Township, both of whi ...

, with her two sons, not wishing to return to England after travelling to the US just before the outbreak of World War II. In the last years of her life, she and her husband travelled extensively, and in 1982, she died at Cambridge.

Early life

Ingham was born on , at Cromer House, Cromer Terrace, Leeds, and baptised an Anglican in theChurch of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

at Donhead St Andrew

Donhead St Andrew is a village and civil parish in Wiltshire, England, on the River Nadder. It lies east of the Dorset market town of Shaftesbury. The parish includes the hamlets of West End, Milkwell and (on the A30) Brook Waters.

Ferne House ...

, Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

, on 14September 1897. She was the youngest daughter of Helen Mary TupperCarey, , and Albert Darell. They had married at Donhead StAndrew on 16May 1890. Helen Mary was the daughter of Reverend Horace Edward Chapman, a former rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of Donhead StAndrew, and Adelaide Maria, néeFletcher.

Ingham's father was the son of the Reverend Tupper Carey and Helen Jane, néeSandeman. He was educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, and trained at Cuddesdon Theological College. He was curate of Leeds before being appointed rector of St Margaret's Church, Lowestoft. In 1910, he was appointed canon residentiary of

Ingham's father was the son of the Reverend Tupper Carey and Helen Jane, néeSandeman. He was educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, and trained at Cuddesdon Theological College. He was curate of Leeds before being appointed rector of St Margaret's Church, Lowestoft. In 1910, he was appointed canon residentiary of York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, and later, became vicar

A vicar (; Latin: '' vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pre ...

of Huddersfield

Huddersfield is a market town in the Kirklees district in West Yorkshire, England. It is the administrative centre and largest settlement in the Kirklees district. The town is in the foothills of the Pennines. The River Holme's confluence into ...

. From 1938, he was Chaplain to the King

An Honorary Chaplain to the King (KHC) is a member of the clergy within the United Kingdom who, through long and distinguished service, is appointed to minister to the monarch of the United Kingdom. When the reigning monarch is female, Honorary Ch ...

and at Monte Carlo

Monte Carlo (; ; french: Monte-Carlo , or colloquially ''Monte-Carl'' ; lij, Munte Carlu ; ) is officially an administrative area of the Principality of Monaco, specifically the ward of Monte Carlo/Spélugues, where the Monte Carlo Casino is ...

. Despite his given name being Albert Darell, he was known as "Tupper" to his friends and was described by John Gilbert Lockhart in Cosmo Gordon Lang's biography as follows:

Ingham had four siblings. Her eldest sister, Jacqueline Marjorie, married the Reverend Edgar James Mitchell, and after their marriage, they undertook missionary

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

work in the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

. Ingham's elder sister, Edith, known as "Betty" to her friends and family, married the author Michael Sadleir

Michael Sadleir (25 December 1888 – 13 December 1957), born Michael Thomas Harvey Sadler, was a British publisher, novelist, book collector, and bibliographer.

Biography

Michael Sadleir was born in Oxford, England, the son of Sir Michael ...

. Sadleir was the only son of Sir Michael Ernest Sadler

Sir Michael Ernest Sadler (3 July 1861 – 14 October 1943) was an English historian, educationalist and university administrator. He worked at Victoria University of Manchester and was the vice-chancellor of the University of Leeds. He was als ...

, a former vice-chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth and former Commonwealth nations, the chancellor ...

of the University of Leeds. Her elder brother, Humphrey Darell , was a tea planter in British East Africa

East Africa Protectorate (also known as British East Africa) was an area in the African Great Lakes occupying roughly the same terrain as present-day Kenya from the Indian Ocean inland to the border with Uganda in the west. Controlled by Bri ...

before the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. He was commissioned a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

in the King's African Rifles

The King's African Rifles (KAR) was a multi-battalion British colonial regiment raised from Britain's various possessions in East Africa from 1902 until independence in the 1960s. It performed both military and internal security functions within ...

, but was severely wounded in the right thigh during the East African campaign. He married Marjorie Gertrude Drakes, née Bredin, the widow of Charles Henry Drakes. In later life, he worked for the Colonial Service

The Colonial Service, also known as His/Her Majesty's Colonial Service and replaced in 1954 by Her Majesty's Overseas Civil Service (HMOCS), was the British government service that administered most of Britain's overseas possessions, under the aut ...

in Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

and was appointed a Companion of the Imperial Service Order

The Imperial Service Order was established by King Edward VII in August 1902. It was awarded on retirement to the administration and clerical staff of the Civil Service throughout the British Empire for long and meritorious service. Normally a pe ...

in the Queen's 1959 Birthday Honours. Her younger brother, Peter Charles Sandeman, was a captain in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

. He married Anne Ethel Violet Montagu Dundas, the eldest daughter of Robert Neville Dundas and Cecil Mary, née Lancaster.

Education

Ingham was educated at Claire House School, an all girl school in North Parade, Lowestoft, which specialised in the teaching of French. At the age of ten, she gained a prize in preliminary French examinations that were organised by the National Society of French Professors in England. She competed against candidates from the "best girls' schools in England", the written tests consisting of translation and composition (prose and poetry), essay, and questions on 17th to 19thcentury French literature. In the same year, she performed as ''Philaminte'' in the school's production of three scenes from

Ingham was educated at Claire House School, an all girl school in North Parade, Lowestoft, which specialised in the teaching of French. At the age of ten, she gained a prize in preliminary French examinations that were organised by the National Society of French Professors in England. She competed against candidates from the "best girls' schools in England", the written tests consisting of translation and composition (prose and poetry), essay, and questions on 17th to 19thcentury French literature. In the same year, she performed as ''Philaminte'' in the school's production of three scenes from Molière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (, ; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, , ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the greatest writers in the French language and worl ...

's '' Les Femmes Savantes''.

Ingham showed an early interest in botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

. In her youth, she would collect wildflowers to display at local parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one o ...

shows. Her grandmother, Helen Jane Carey, was a keen amateur botanist and specimen collector, a popular and fashionable pastime in Victorian England

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

. In 1916, Ingham entered the University of Leeds to study botany and, within three years, was a research student in the botany department at Leeds, studying water absorption at the growing point of plant roots. In 1919, Ingham studied general zoology at the Citadel Hill Laboratory of the Marine Biological Association, Plymouth. Annie Redman King, her friend from Weetwood Hall in Leeds, was a Ray Lankester

Sir Edwin Ray Lankester (15 May 1847 – 13 August 1929) was a British zoologist.New International Encyclopaedia.

An invertebrate zoologist and evolutionary biologist, he held chairs at University College London and Oxford University. He was th ...

investigator at the laboratory.

Career

In January 1922, Ingham was appointed a research assistant in the botany department, where

In January 1922, Ingham was appointed a research assistant in the botany department, where Joseph Hubert Priestley

Joseph Hubert Priestley (; 5 October 188331 October 1944) was a British lecturer in botany at University College, Bristol, and professor of botany and pro-vice-chancellor at the University of Leeds. He has been described as a gifted teacher w ...

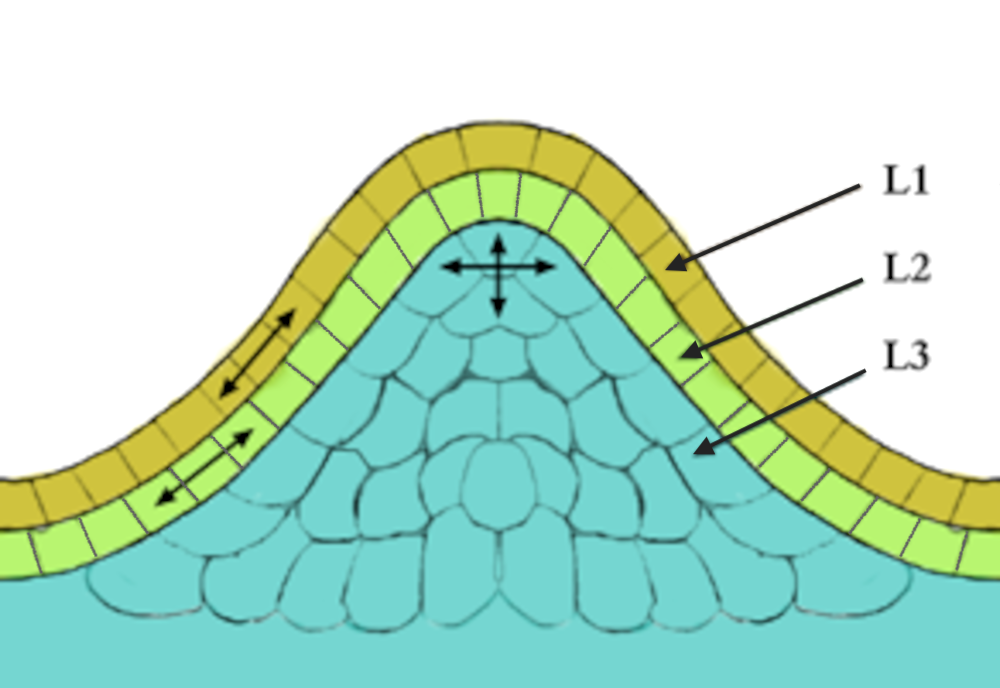

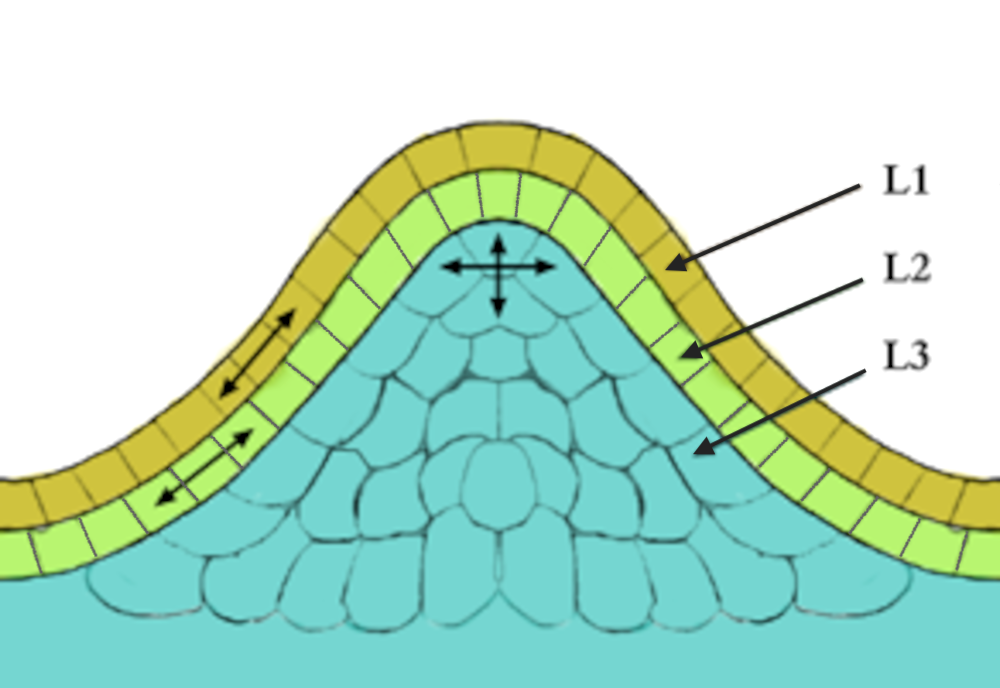

was Dean of the Faculty of Science. She and Priestley were the first to isolate cell walls from meristem

The meristem is a type of tissue found in plants. It consists of undifferentiated cells (meristematic cells) capable of cell division. Cells in the meristem can develop into all the other tissues and organs that occur in plants. These cells conti ...

atic tissues in ''Vicia faba

''Vicia faba'', commonly known as the broad bean, fava bean, or faba bean, is a species of vetch, a flowering plant in the pea and bean family Fabaceae. It is widely cultivated as a crop for human consumption, and also as a cover crop. Varieti ...

'' (broad beans). They analysed the walls for protein, cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell w ...

, and pectin, and concluded that the walls contained protein. They also studied when cellulose is first produced by plants, the differences in shoot and root development, and the role of the cork cambium

Cork cambium (pl. cambia or cambiums) is a tissue found in many vascular plants as a part of the epidermis. It is one of the many layers of bark, between the cork and primary phloem. The cork cambium is a lateral meristem and is responsible for ...

. These plant physiology studies were followed by two ''New Phytologist

''New Phytologist'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal published on behalf of the New Phytologist Foundation by Wiley-Blackwell. It was founded in 1902 by botanist Arthur Tansley, who served as editor until 1931.

Topics covered

''New Phytolo ...

'' papers. She later provided unpublished results from these experiments on broad bean embryos to the British botanist William Pearsall

William Harold Pearsall (23 July 1891 – 14 October 1964) was a British botanist, Quain Professor of Botany at University College London 1944–1957.‘PEARSALL, William Harold’, Who Was Who, A & C Black, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing pl ...

. Described as a "brilliant scholar", she was awarded a MSc degree on 28June 1928, for her research work and thesis titled '.

In February 1930, Ingham joined the Imperial Bureau of Plant and Crop Genetics, at the Plant Breeding Institute

The Plant Breeding Institute was an agricultural research organisation in Cambridge in the United Kingdom between 1912 and 1987.

Founding

The institute was established in 1912 as part of the School of Agriculture at the University of Cambridge. ...

, Cambridge, as a translator and scientific officer. Sir Rowland Biffen was the first director of the Cambridge bureau, and her supervisor, Penrhyn Stanley Hudson , was deputy director. She was fluent in French, Italian, German and Swedish, and as a whole, the bureau had been capable of dealing with Spanish, Dutch, and Russian. Abstracts were written on various aspects of plant breeding and genetics, with some of the foreign language papers requiring more complete translations. These abstracts were published in a quarterly journal called ''Plant Breeding Abstracts''. In 1931, she attended the eighth conference of the Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux (ASLIB) at Oxford, where progress on ASLIB's newlyformed panel of expert translators was discussed. After her marriage, she worked from home translating most of the German documents, and in 1939, was put in charge of the bureau after Hudson fell ill.

Personal life

Around 1922, Ingham sat for a portrait by William Roberts, the "English Cubist" artist. The finished painting was titled "Portrait of Miss Jane TupperCarey" and was shown for the first time in November 1923 at New Chenil Galleries, Chelsea. By 1926, she had been appointed subwarden at Weetwood Hall, the then university hall of residence for women students. In the same year, she was appointed the first honorary secretary of the Leeds branch of the BritishItalian League. The League's aims were to found a chair in Italian at the University of Leeds and foster relations between the two countries. In the late 1920s, Ingham joined the Leeds University Amateurs, the university's

In the late 1920s, Ingham joined the Leeds University Amateurs, the university's amateur dramatics

An amateur () is generally considered a person who pursues an avocation independent from their source of income. Amateurs and their pursuits are also described as popular, informal, self-taught, user-generated, DIY, and hobbyist.

History

Hist ...

society, acting in several wellreceived roles, such as ''Sybil Bumont'' in ''The Watched Pot

''The Watched Pot'' (alternative title ''The Mistress of Briony'') is a romantic comedy play by Saki and Charles Maude published in 1924. The play, all three acts of which are set in the fictional English country house of Briony Manor, revolves ...

''. In December 1928, she took part in a fashion show of dresses through the ages at the Albion Hall, Leeds, in aid of StFaith's Homes. She wore a high-waisted, skintight coat of red cloth edged with fur, a long blue skirt trimmed with six rows of black velvet, and a feather toque

A toque ( or ) is a type of hat with a narrow brim or no brim at all.

Toques were popular from the 13th to the 16th century in Europe, especially France. The mode was revived in the 1930s. Now it is primarily known as the traditional headgear ...

. Her appearance was greeted with "shrieks of laughter" from the audience.

She married Albert Ingham

Albert Edward Ingham (3 April 1900 – 6 September 1967) was an English mathematician.

Early life and education

Ingham was born in Northampton. He went to Stafford Grammar School and began his studies at Trinity College, Cambridge in January ...

on 6July 1932 at St Edward's Church, Cambridge, in a private ceremony attended only by her parents, sister Edith, brotherinlaw Michael Sadleir, who gave her away, and Redman King. They had met after he had been appointed reader

A reader is a person who reads. It may also refer to:

Computing and technology

* Adobe Reader (now Adobe Acrobat), a PDF reader

* Bible Reader for Palm, a discontinued PDA application

* A card reader, for extracting data from various forms of ...

in mathematical analysis

Analysis is the branch of mathematics dealing with continuous functions, limit (mathematics), limits, and related theories, such as Derivative, differentiation, Integral, integration, measure (mathematics), measure, infinite sequences, series (m ...

at the University of Leeds in 1926. Their engagement announcement in May 1932 had come as surprise to their circle of friends in Leeds, as there had been no indication that they were romantically involved. However, they had been quietly engaged with plans to announce it after lectures ended.

In July 1939, Albert was awarded a Leverhulme Research Fellowship to study analytic number theory at the Institute for Advanced Study

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), located in Princeton, New Jersey, in the United States, is an independent center for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry. It has served as the academic home of internationally preeminent schola ...

(IAS) in Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ni ...

, New Jersey. At that point, they had two sons, Michael Frank and Stephen Darell, and the entire family sailed from Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

to New York on 1September 1939. However, just two days into their voyage, Britain declared war on Germany. They were hesitant to bring their family back due to reports from Europe containing speculation of imminent total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all civilian-associated resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilizes all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare over non-combata ...

. Consequently, they made the decision to keep the family in Princeton, except for Albert, who had returned to England by 1942. Alan Pars, godfather to their son Michael, later recommended Albert for an Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

post in America knowing that Ingham and the children were still there.

Later life and death

The Inghams owned a punt, called ''Pete'', moored in the River Cam, and it was used regularly during the summer for trips and picnics. They also went on many trips abroad, including India, and walking holidays in the

The Inghams owned a punt, called ''Pete'', moored in the River Cam, and it was used regularly during the summer for trips and picnics. They also went on many trips abroad, including India, and walking holidays in the French Alps

The French Alps are the portions of the Alps mountain range that stand within France, located in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur regions. While some of the ranges of the French Alps are entirely in France, others, such as ...

. It was on such a holiday that Albert died of a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

on a high path near Haute-Savoie

Haute-Savoie (; Arpitan: ''Savouè d'Amont'' or ''Hiôta-Savouè''; en, Upper Savoy) or '; it, Alta Savoia. is a department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of Southeastern France, bordering both Switzerland and Italy. Its prefecture is Ann ...

, southeastern France. After his death, she resisted offers for her husband's mathematical notes and papers, instead keeping the papers in a cupboard at the house.

Jane Ingham died at Cambridge on 10September 1982, and was cremated at the Cambridge City Crematorium, Huntingdon Road, Dry Drayton

Dry Drayton is a village and civil parish about 5 miles (8 km) northwest of Cambridge in Cambridgeshire, England, listed as Draitone in the Domesday Book in 1086. It covers an area of .

History

The ancient parish of Dry Drayton formed betwe ...

, on 20September 1982. Alan Pars, her friend and her husband's former colleague at Cambridge, sent a wreath.

Legacy

Discovery of protein in plant cell walls

Ingham and Priestley were the first to isolate cell walls from the middle lamella of theradicle

In botany, the radicle is the first part of a seedling (a growing plant embryo) to emerge from the seed during the process of germination. The radicle is the embryonic root of the plant, and grows downward in the soil (the shoot emerges from ...

and plumule meristems of ''Vicia faba''. They analysed the cell walls for protein, cellulose, and pectin. They noted that the cellulose walls of the radicle failed to react with iodine and sulphuric acid, or with of zinc. They showed that the cellulose in the wall of the radicle is masked by other substances, particularly proteins and fatty acid

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, ...

s. In the plumule, cellulose is associated with greater quantities of pectin, but less protein and fatty acid, particularly when the adult parenchyma is grown in light.

postdoctoral researcher

A postdoctoral fellow, postdoctoral researcher, or simply postdoc, is a person professionally conducting research after the completion of their doctoral studies (typically a PhD). The ultimate goal of a postdoctoral research position is to pu ...

in biochemistry

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology and ...

at Birkbeck College, questioned their results and concluded that less than 0.001% of protein was found in the cell walls of the plants examined. Later researchers found protein in the cells but were unable to rule out the possibility of cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. ...

ic contamination. It is now known that the middle lamella consists of a pectic polysaccharide-rich material. However, the material properties and molecular organisation of the middle lamella are still not fully understood.

Differences in cell division and elongation in the epidermal layer of plants

Ingham found that in the arch of thehypocotyl

The hypocotyl (short for "hypocotyledonous stem", meaning "below seed leaf") is the stem of a germinating seedling, found below the cotyledons (seed leaves) and above the radicle ( root).

Eudicots

As the plant embryo grows at germination, it se ...

from sunflower seeds, '' Helianthus annuus'', there are considerably more cells on the outside than on the inside. Counting from the beginning to the end of the arch, the result was "3,299 cells on the upper side as against 1,531 on the lower." This result means that the convex side of the arch leads the concave side, not only in terms of cell extension, but also in cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukaryotes, there ar ...

behaviour, such that a different division rate would cause the growth difference. Consequently, the concave and convex sides show profound physiological differences. The observation that in the hypocotyl the cells on the convex side are considerably larger than those on the inside could be explained by the uneven transverse transport of the growth hormone auxin. Auxin has a strengthening effect on the elongation growth of the cells. In the case of nutation phenomena, it is possible that curvature only occurs in a narrowly limited section of the shoot.

Harald Kaldewey, professor of botany at Saarland University

Saarland University (german: Universität des Saarlandes, ) is a public research university located in Saarbrücken, the capital of the German state of Saarland. It was founded in 1948 in Homburg in co-operation with France and is organized in s ...

in Saarbrücken, Germany, measured the differences in the length of the subepidermal cells on the outer and inner periphery of the arch in the nutation curvature of the pedicel

Pedicle or pedicel may refer to:

Human anatomy

*Pedicle of vertebral arch, the segment between the transverse process and the vertebral body, and is often used as a radiographic marker and entry point in vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty procedures

...

s of snake's head fritillary, ''Fritillaria meleagris

''Fritillaria meleagris'' is a Eurasian species of flowering plant in the lily family Liliaceae. Its common names include snake's head fritillary, snake's head (the original English name), chess flower, frog-cup, guinea-hen flower, guinea flower, ...

''. The result was expected if the curvature is based exclusively on differences in elongation growth. A difference in width between the sub-epidermal cells of the outer and inner periphery of the arch of curvature was not found. Sir Edward James Salisbury, the English botanist and ecologist, found good agreement between the ratio of the epidermal cell lengths and the arch lengths of the nutation curvature of the epicotyl An epicotyl is important for the beginning stages of a plant's life. It is the region of a seedling stem above the stalks of the seed leaves of an embryo plant. It grows rapidly, showing hypogeal germination, and extends the stem above the soil surf ...

in seedlings of different woody plants. The findings of Ingham, Salisbury, and Kaldewey, do not necessarily contradict each other as the epidermis and sub-epidermal layer may well behave differently than cortical layers in terms of division and extension growth.

Importance of cell orientation in cork

In Ingham's last study in the botany department at the University of Leeds, she

In Ingham's last study in the botany department at the University of Leeds, she ringbarked

Girdling, also called ring-barking, is the complete removal of the bark (consisting of cork cambium or "phellogen", phloem, cambium and sometimes going into the xylem) from around the entire circumference of either a branch or trunk of a woody ...

''Laburnum

''Laburnum'', sometimes called golden chain or golden rain, is a genus of two species of small trees in the subfamily Faboideae of the pea family Fabaceae. The species are '' Laburnum anagyroides''—common laburnum and '' Laburnum alpinum''� ...

'' and sycamore ('' Acer pseudoplatanus'') trees, but left zigzag

A zigzag is a pattern made up of small corners at variable angles, though constant within the zigzag, tracing a path between two parallel lines; it can be described as both jagged and fairly regular.

In geometry, this pattern is described as ...

bridges of tissue with horizontal portions linking the bark above and below the cut. At first, the lack of pressure within these bridges resulted in the formation of callus

A callus is an area of thickened and sometimes hardened skin that forms as a response to repeated friction, pressure, or other irritation. Since repeated contact is required, calluses are most often found on the feet and hands, but they may o ...

like tissue, and the cambial initials, by repeated division, came to resemble ray cells. At a later stage, some of this mass of (roughly spherical) cells became elongated horizontally in the direction of the bridge tissue. Xylem

Xylem is one of the two types of transport tissue in vascular plants, the other being phloem. The basic function of xylem is to transport water from roots to stems and leaves, but it also transports nutrients. The word ''xylem'' is derived from ...

and phloem

Phloem (, ) is the living tissue in vascular plants that transports the soluble organic compounds made during photosynthesis and known as ''photosynthates'', in particular the sugar sucrose, to the rest of the plant. This transport process is c ...

formed in the horizontal portion of the bridge with its tracheary elements extended in a horizontal direction. It has been postulated that calluses are formed because the cambium

A cambium (plural cambia or cambiums), in plants, is a tissue layer that provides partially undifferentiated cells for plant growth. It is found in the area between xylem and phloem. A cambium can also be defined as a cellular plant tissue from w ...

cells cannot function correctly under a change of orientation. For example, the altered direction of sap flow might affect the direction of cambial cell growth. Pressure, nutrient movements, and cambial auxin transport have also been suggested as causes.

Publications

As author

* * Refereed by William Lawrence Balls in May 1923. * * * *As experimental collaborator

* * * *See also

Footnotes

References

Further reading

* * * Archbishop Cosmo Lang's biography of Ingham's father. *External links

Portrait

of Ingham by William Roberts, circa 1922, "An English Cubist".

Afterimages: Photographs as an External Autobiographical Memory System and a Contemporary Art Practice

University of the Arts London Research Online. Photographs of Jane Ingham, taken by Albert Ingham, for Mark Ingham's PhD thesis at

Goldsmiths, University of London

Goldsmiths, University of London, officially the Goldsmiths' College, is a constituent research university of the University of London in England. It was originally founded in 1891 as The Goldsmiths' Technical and Recreative Institute by the Wo ...

.

Works by Ingham

at

WorldCat

WorldCat is a union catalog that itemizes the collections of tens of thousands of institutions (mostly libraries), in many countries, that are current or past members of the OCLC global cooperative. It is operated by OCLC, Inc. Many of the O ...

.

Lorna Scott and her Mortar Board

by Margaret Stewart, for Egham Museum, on botanist Lorna Iris Scott, Joseph Hubert Priestley's collaborator after Ingham left for Cambridge. {{DEFAULTSORT:Ingham, Jane 1897 births 1982 deaths 20th-century British botanists 20th-century British women scientists 20th-century English people 20th-century English women Academics of the University of Leeds Alumni of the University of Leeds British translators British women botanists English botanists German–English translators People from Cambridge People from Leeds Women botanists