James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, and diplomat who served as the fifth

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

from 1817 to 1825. A member of the

Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

, Monroe was the last president who was a

Founding Father

The following list of national founding figures is a record, by country, of people who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e. ...

as well as the last president of the

Virginia dynasty and the

Republican Generation;

his presidency coincided with the

Era of Good Feelings

The Era of Good Feelings marked a period in the political history of the United States that reflected a sense of national purpose and a desire for unity among Americans in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The era saw the collapse of the Fed ...

, concluding the

First Party System

The First Party System is a model of American politics used in history and political science to periodize the political party system that existed in the United States between roughly 1792 and 1824. It featured two national parties competing for ...

era of American politics. He is perhaps best known for issuing the

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile ac ...

, a policy of opposing European colonialism in the

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

while effectively asserting U.S. dominance, empire, and hegemony in the hemisphere. He also served as governor of

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, a member of the

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

, U.S. ambassador to

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, the seventh

Secretary of State, and the eighth

Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

.

Born into a

slave-owning planter family in

Westmoreland County,

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, Monroe served in the

Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

during the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. After studying law under

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

from 1780 to 1783, he served as a

delegate

Delegate or delegates may refer to:

* Delegate, New South Wales, a town in Australia

* Delegate (CLI), a computer programming technique

* Delegate (American politics), a representative in any of various political organizations

* Delegate (Unit ...

in the

Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

. As a delegate to the

Virginia Ratifying Convention

The Virginia Ratifying Convention (also historically referred to as the "Virginia Federal Convention") was a convention of 168 delegates from Virginia who met in 1788 to ratify or reject the United States Constitution, which had been drafted at ...

, Monroe opposed the ratification of the

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

. In 1790, he won election to the

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, where he became a leader of the Democratic-Republican Party. He left the Senate in 1794 to serve as President

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

's ambassador to France but was recalled by Washington in 1796. Monroe won the election as

Governor of Virginia

The governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia serves as the head of government of Virginia for a four-year term. The incumbent, Glenn Youngkin, was sworn in on January 15, 2022.

Oath of office

On inauguration day, the Governor-elect takes th ...

in 1799 and strongly supported Jefferson's candidacy in the

1800 presidential election.

As President Jefferson's special envoy, Monroe helped negotiate the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

, through which the United States nearly doubled in size. Monroe fell out with his longtime friend

James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

after Madison rejected the

Monroe–Pinkney Treaty

The Monroe–Pinkney Treaty was a treaty drawn up in 1806 by diplomats of the United States and Great Britain to renew the 1795 Jay Treaty. As it was rejected by President Thomas Jefferson, it never took effect. The treaty was negotiated by the m ...

that Monroe negotiated with Britain. He unsuccessfully challenged Madison for the Democratic-Republican nomination in the

1808 presidential election, but in 1811 he joined Madison's administration as Secretary of State. During the later stages of the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, Monroe simultaneously served as Madison's Secretary of State and Secretary of War. Monroe's wartime leadership established him as Madison's

heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

, and he easily defeated

Federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

candidate

Rufus King in the

1816 presidential election.

During Monroe's tenure as president, the Federalist Party collapsed as a national political force and Monroe was re-elected, virtually unopposed, in

1820. As president, Monroe signed the

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and ...

, which admitted Missouri as a

slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

and banned slavery from territories north of the 36°30′ parallel. In foreign affairs, Monroe and Secretary of State

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

favored a policy of conciliation with Britain and a policy of expansionism against the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

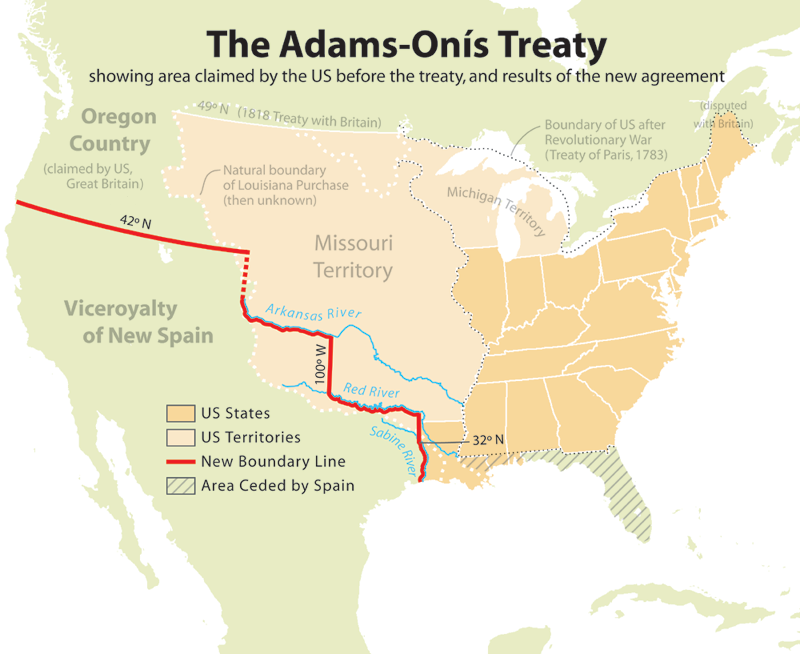

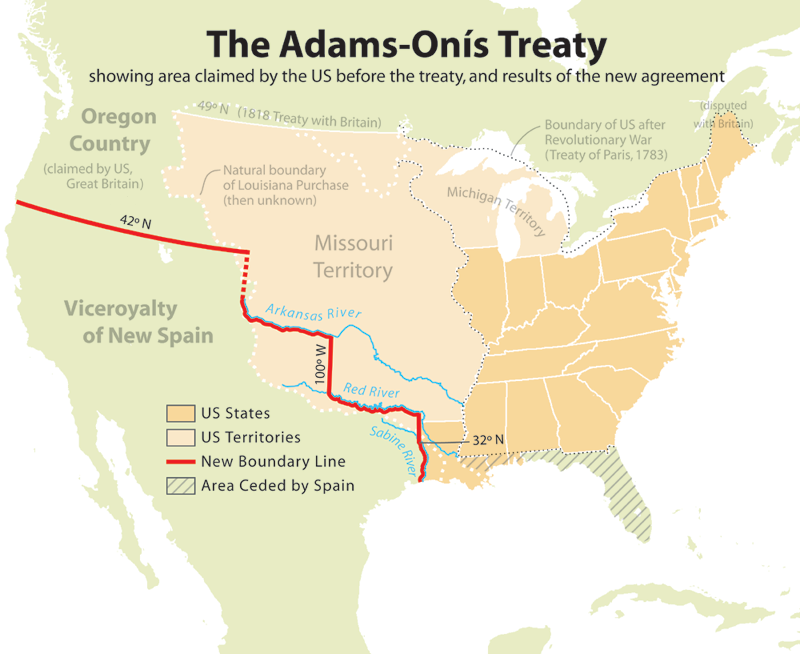

. In the 1819

Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and defined t ...

with Spain, the United States secured

Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

and established its western border with

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

. In 1823, Monroe announced the United States' opposition to any European intervention in the

recently independent countries of the Americas with the Monroe Doctrine, which became a landmark in American foreign policy. Monroe was a member of the

American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America until 1837, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the migration of freebor ...

, which supported the colonization of Africa by freed

slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, and

Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

's capital of

Monrovia

Monrovia () is the capital city of the West African country of Liberia. Founded in 1822, it is located on Cape Mesurado on the Atlantic coast and as of the 2008 census had 1,010,970 residents, home to 29% of Liberia’s total population. As the ...

is named in his honor.

Following his retirement in 1825, Monroe was plagued by financial difficulties, and died on July 4, 1831, in

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

— sharing a distinction with Presidents

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

and Thomas Jefferson of dying on the

anniversary of U.S independence. Historians have

generally ranked him as an above-average president.

Early life

James Monroe was born April 28, 1758, in his parents' house in a wooded area of

Westmoreland County,

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. The marked site is one mile from the unincorporated community known today as

Monroe Hall, Virginia

Monroe Hall is an unincorporated community in Westmoreland County, Virginia, United States. The site of James Monroe's birthplace is located in the community, and is marked with an obelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; dim ...

. The

James Monroe Family Home Site was listed on the

National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

in 1979. His father Spence Monroe (1727–1774) was a moderately prosperous planter and slave owner who also practiced carpentry. His mother Elizabeth Jones (1730–1772) married Spence Monroe in 1752 and they had five children: Elizabeth, James, Spence, Andrew, and Joseph Jones.

[.]

His paternal great-great-grandfather Patrick Andrew Monroe emigrated to America from

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

in the mid-17th century, and was part of an ancient Scottish clan known as

Clan Munro

Clan Munro (; gd, Clann an Rothaich ) is a Highland Scottish clan. Historically the clan was based in Easter Ross in the Scottish Highlands. Traditional origins of the clan give its founder as Donald Munro who came from the north of Ireland and ...

. In 1650 he patented a large tract of land in Washington Parish,

Westmoreland County, Virginia

Westmoreland County is a county located in the Northern Neck of the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population sits at 18,477. Its county seat is Montross.

History

As originally established by the Virginia colony's ...

. Monroe's mother was the daughter of James Jones, who immigrated from

Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

and settled in nearby

King George County, Virginia. Jones was a wealthy architect.

Also among James Monroe's ancestors were

French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Beza ...

immigrants, who came to Virginia in 1700.

At age 11, Monroe was enrolled in Campbelltown Academy, the lone school in the county. He attended this school only 11 weeks a year, as his labor was needed on the farm. During this time, Monroe formed a lifelong friendship with an older classmate,

John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longes ...

. Monroe's mother died in 1772, and his father two years later. Though he inherited property, including slaves, from both of his parents, the 16-year-old Monroe was forced to withdraw from school to support his younger brothers. His childless maternal uncle,

Joseph Jones, became a surrogate father to Monroe and his siblings. A member of the

Virginia House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses was the elected representative element of the Virginia General Assembly, the legislative body of the Colony of Virginia. With the creation of the House of Burgesses in 1642, the General Assembly, which had been established ...

, Jones took Monroe to the capital of

Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it had a population of 15,425. Located on the Virginia Peninsula ...

, and enrolled him in the

College of William and Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William III a ...

. Jones also introduced Monroe to important Virginians such as

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

,

Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736June 6, 1799) was an American attorney, planter, politician and orator known for declaring to the Second Virginia Convention (1775): " Give me liberty, or give me death!" A Founding Father, he served as the first an ...

, and

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

. In 1774, opposition to the British government grew in the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

in reaction to the "

Intolerable Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measure ...

", and Virginia sent a delegation to the

First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from 12 of the 13 British colonies that became the United States. It met from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, after the British Navy ...

. Monroe became involved in the opposition to

Lord Dunmore

Earl of Dunmore is a title in the Peerage of Scotland.

History

The title was created in 1686 for Lord Charles Murray, second son of John Murray, 1st Marquess of Atholl. He was made Lord Murray of Blair, Moulin and Tillimet (or Tullimet) and V ...

, the colonial governor of Virginia, and took part in the storming of the

Governor's Palace.

Revolutionary War service

In early 1776, about a year and a half after his enrollment, Monroe dropped out of college and joined the 3rd Virginia Regiment in the

Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

. As the fledgling army valued literacy in its officers, Monroe was commissioned with the rank of lieutenant, serving under Captain

William Washington

William Washington (February 28, 1752 – March 6, 1810) was a cavalry officer of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, who held a final rank of brigadier general in the newly created United States after the war. Primarily ...

. After months of training, Monroe and 700 Virginia infantrymen were called north to serve in the

New York and New Jersey campaign

The New York and New Jersey campaign in 1776 and the winter months of 1777 was a series of American Revolutionary War battles for control of the Port of New York and New Jersey, Port of New York and the state of New Jersey, fought between Kingdom ...

. Shortly after the Virginians arrived, George Washington led the army in a retreat from

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

into New Jersey and then across the

Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

into Pennsylvania. In late December, Monroe took part in a surprise attack on a

Hessian encampment at the

Battle of Trenton. Though the attack was successful, Monroe suffered a severed artery in the battle and nearly died. In the aftermath, Washington cited Monroe and William Washington for their bravery, and promoted Monroe to captain. After his wounds healed, Monroe returned to Virginia to recruit his own company of soldiers. His participation in the battle was memorialized in

John Trumbull

John Trumbull (June 6, 1756November 10, 1843) was an American artist of the early independence period, notable for his historical paintings of the American Revolutionary War, of which he was a veteran. He has been called the "Painter of the Rev ...

's painting ''

The Capture of the Hessians at Trenton, December 26, 1776

''The Capture of the Hessians at Trenton, December 26, 1776'' is the title of an oil painting by the American artist John Trumbull depicting the capture of the Hessian soldiers at the Battle of Trenton on the morning of Thursday, December 26, 1 ...

'' as well as

Emanuel Leutze

Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze (May 24, 1816July 18, 1868) was a German-American history painter best known for his 1851 painting '' Washington Crossing the Delaware''. He is associated with the Düsseldorf school of painting.

Biography

Leutze was born ...

's 1851 ''

Washington Crossing the Delaware.''

Lacking the wealth to induce soldiers to join his company, Monroe instead asked his uncle to return him to the front. Monroe was assigned to the staff of General

William Alexander, Lord Stirling

William Alexander, also known as Lord Stirling (1726 – 15 January 1783), was a Scottish-American major general during the American Revolutionary War. He was considered male heir to the Scottish title of Earl of Stirling through Scottish lin ...

. During this time he formed a close friendship with the

Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revoluti ...

, a French volunteer who encouraged him to view the war as part of a wider struggle against religious and political tyranny. Monroe served in the

Philadelphia campaign

The Philadelphia campaign (1777–1778) was a British effort in the American Revolutionary War to gain control of Philadelphia, which was then the seat of the Second Continental Congress. British General William Howe, after failing to dra ...

and spent the winter of 1777–78 at the encampment of

Valley Forge

Valley Forge functioned as the third of eight winter encampments for the Continental Army's main body, commanded by General George Washington, during the American Revolutionary War. In September 1777, Congress fled Philadelphia to escape the B ...

, sharing a log hut with Marshall. After serving in the

Battle of Monmouth

The Battle of Monmouth, also known as the Battle of Monmouth Court House, was fought near Monmouth Court House in modern-day Freehold Borough, New Jersey on June 28, 1778, during the American Revolutionary War. It pitted the Continental Army, co ...

, the destitute Monroe resigned his commission in December 1778 and joined his uncle in Philadelphia. After the British

captured Savannah, the Virginia legislature decided to raise four regiments, and Monroe returned to his native state, hoping to receive his own command. With letters of recommendation from Washington, Stirling, and

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

, Monroe received a commission as a lieutenant colonel and was expected to lead one of the regiments, but recruitment again proved to be a problem. On Jones's advice, Monroe returned to Williamsburg to study law, becoming a protege of Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson.

With the British increasingly focusing their operations in the

Southern colonies, the Virginians moved the capital to the more defensible city of

Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

, and Monroe accompanied Jefferson to the new capital. As governor of Virginia, Jefferson held command over its militia, and made Monroe a colonel. Monroe established a messenger network to coordinate with the Continental Army and other state militias. Still unable to raise an army due to a lack of interested recruits, Monroe traveled to his home in King George County, and thus was not present for the British

raid of Richmond

The Raid on Richmond was a series of British military actions against the capital of Virginia, Richmond, and the surrounding area, during the American Revolutionary War. Led by American turncoat Benedict Arnold, the Richmond Campaign is cons ...

. As both the Continental Army and the Virginia militia had an abundance of officers, Monroe did not serve during the

Yorktown campaign

The Yorktown campaign, also known as the Virginia campaign, was a series of military maneuvers and battles during the American Revolutionary War that culminated in the siege of Yorktown in October 1781. The result of the campaign was the surren ...

, and, much to his frustration, did not take part in the

Siege of Yorktown

The Siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown, the surrender at Yorktown, or the German battle (from the presence of Germans in all three armies), beginning on September 28, 1781, and ending on October 19, 1781, at Yorktown, Virgi ...

. Although

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

served as a courier in a militia unit at age 13, Monroe is regarded as the last U.S. president who was a

Revolutionary War veteran, since he served as an officer of the Continental Army and took part in combat. As a result of his service, Monroe became a member of the

Society of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of military officers wh ...

.

Monroe resumed studying law under Jefferson and continued until 1783.

He was not particularly interested in legal theory or practice, but chose to take it up because he thought it offered "the most immediate rewards" and could ease his path to wealth, social standing, and political influence.

Monroe was admitted to the Virginia bar and practiced in

Fredericksburg, Virginia

Fredericksburg is an independent city located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 27,982. The Bureau of Economic Analysis of the United States Department of Commerce combines the city of Fredericksburg wi ...

.

Marriage and family

On February 16, 1786, Monroe married

Elizabeth Kortright (1768–1830) in New York City. She was the daughter of Hannah Aspinwall Kortright and Laurence Kortright, a wealthy trader and former British officer. Monroe met her while serving in the Continental Congress.

After a brief honeymoon on

Long Island, New York

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United States and the 18th ...

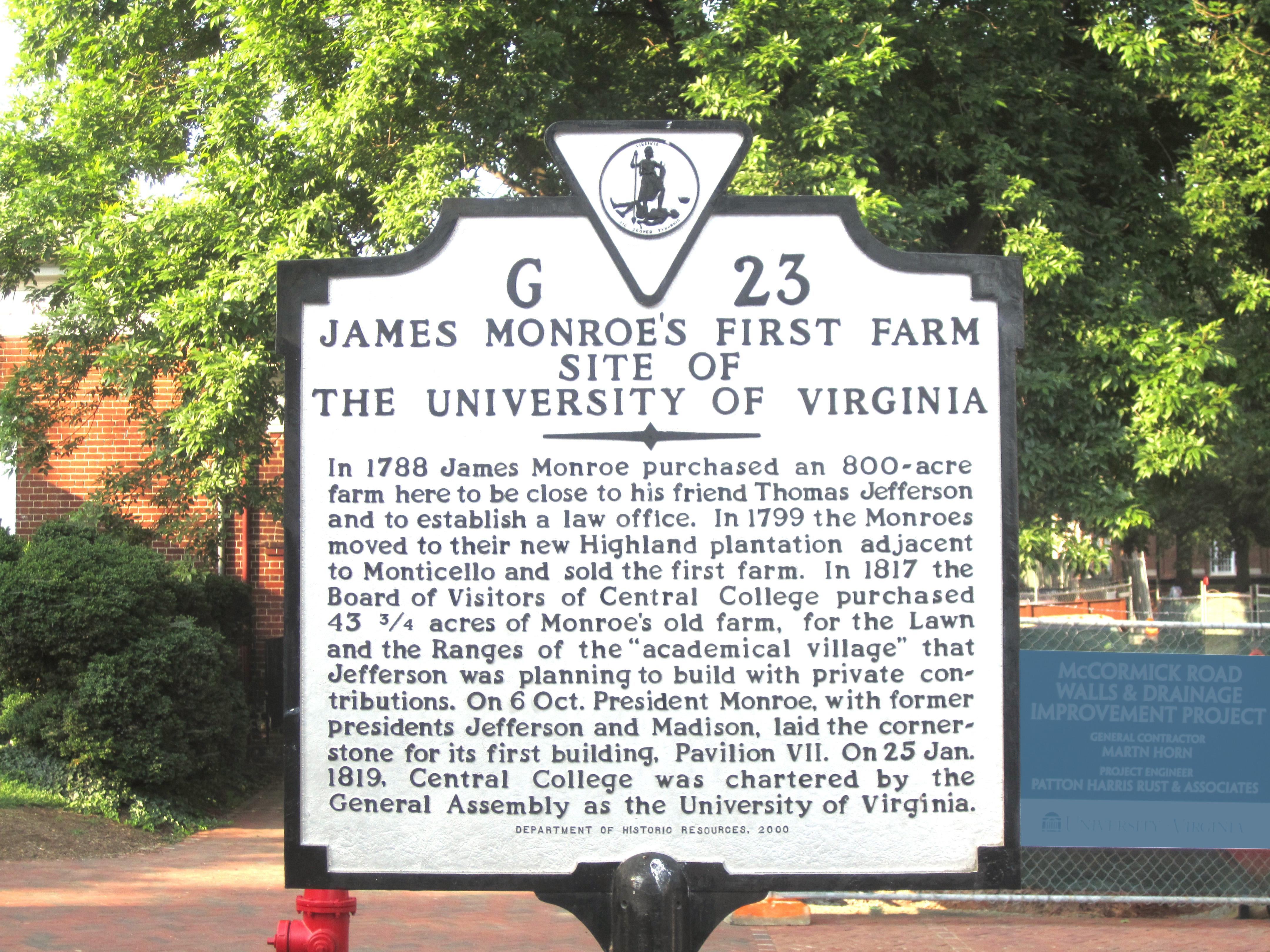

, the Monroes returned to New York City to live with her father until Congress adjourned. They then moved to Virginia, settling in

Charlottesville, Virginia

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Queen Ch ...

, in 1789. They bought an estate in Charlottesville known as

Ash Lawn–Highland, settling on the property in 1799. The Monroes had three children.

*

Eliza Monroe Hay was born in Fredericksburg, Virginia, in 1786, and was educated in Paris at the school of

Madame Campan during the time her father was the United States Ambassador to France. In 1808 she married

George Hay, a prominent Virginia attorney who had served as prosecutor in the trial of

Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805. Burr's legacy is defined by his famous personal conflict with Alexand ...

and later as a U.S. District Judge. She died in 1840.

* James Spence Monroe was born in 1799 and died sixteen months later in 1800.

*

Maria Hester Monroe (1802–1850) married her cousin

Samuel L. Gouverneur

Samuel Laurence Gouverneur (1799 – September 29, 1865) was a lawyer and civil servant who was both nephew and son-in-law to James Monroe, the fifth President of the United States.

Early life

Gouverneur was born in 1799 in New York City. His f ...

on March 8, 1820, in the White House, the first president's child to marry there.

Plantations and slavery

Monroe sold his small Virginia plantation in 1783 to enter law and politics. Although he owned multiple properties over the course of his lifetime, his plantations were never profitable. Although he owned much more land and many more slaves, and speculated in property, he was rarely on site to oversee the operations. Overseers treated the slaves harshly to force production, but the plantations barely broke even. Monroe incurred debts by his lavish and expensive lifestyle and often sold property (including slaves) to pay them off. The labor of Monroe's many slaves were also used to support his daughter and son-in-law, along with a ne'er-do-well brother and his son.

During the course of his presidency, Monroe remained convinced that slavery was wrong and supported private manumission, but at the same time he insisted that any attempt to promote emancipation would cause more problems. Monroe believed that slavery had become a permanent part of southern life, and that it could only be removed on providential terms. Like so many other Upper South slaveholders, Monroe believed that a central purpose of government was to ensure "domestic tranquility" for all. Like so many other Upper South planters, he also believed that the central purpose of government was to empower planters like himself. He feared for public safety in the United States during the era of violent revolution on two fronts. First, from potential class warfare of the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

in which those of the propertied classes were summarily purged in mob violence and then preemptive trials, and second, from possible racial warfare similar to that of the

Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt ...

in which blacks, whites, then mixed-race inhabitants were indiscriminately slaughtered as events there unfolded.

Early political career

Virginia politics

Monroe was elected to the

Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two parts of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-numbe ...

in 1782. After serving on Virginia's Executive Council, he was elected to the

Congress of the Confederation in November 1783 and served in Annapolis until Congress convened in Trenton, New Jersey in June 1784. He had served a total of three years when he finally retired from that office by the rule of rotation. By that time, the government was meeting in the temporary capital of

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. In 1784, Monroe undertook an extensive trip through Western New York and Pennsylvania to inspect the conditions in the Northwest. The tour convinced him that the United States had to pressure Britain to abandon its posts in the region and assert control of the Northwest. While serving in Congress, Monroe became an advocate for western expansion, and played a key role in the writing and passage of the

Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

. The ordinance created the

Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

, providing for federal administration of the territories West of Pennsylvania and North of the

Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

. During this period, Jefferson continued to serve as a mentor to Monroe, and, at Jefferson's prompting, he befriended another prominent Virginian,

James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

.

Monroe resigned from Congress in 1786 to focus on his legal career, and he became an attorney for the state. In 1787, Monroe won election to another term in the Virginia House of Delegates. Though he had become outspoken in his desire to reform the Articles, he was unable to attend the

Philadelphia Convention

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. Although the convention was intended to revise the league of states and first system of government under the Articles of Confederation, the intention fr ...

due to his work obligations. In 1788, Monroe became a delegate to the

Virginia Ratifying Convention

The Virginia Ratifying Convention (also historically referred to as the "Virginia Federal Convention") was a convention of 168 delegates from Virginia who met in 1788 to ratify or reject the United States Constitution, which had been drafted at ...

. In Virginia, the struggle over the ratification of the proposed Constitution involved more than a simple clash between federalists and

anti-federalists

Anti-Federalism was a late-18th century political movement that opposed the creation of a stronger U.S. federal government and which later opposed the ratification of the 1787 Constitution. The previous constitution, called the Articles of Con ...

. Virginians held a full spectrum of opinions about the merits of the proposed change in national government. Washington and Madison were leading supporters;

Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736June 6, 1799) was an American attorney, planter, politician and orator known for declaring to the Second Virginia Convention (1775): " Give me liberty, or give me death!" A Founding Father, he served as the first an ...

and

George Mason

George Mason (October 7, 1792) was an American planter, politician, Founding Father, and delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787, one of the three delegates present who refused to sign the Constitution. His writings, including s ...

were leading opponents. Those who held the middle ground in the ideological struggle became the central figures. Led by Monroe and

Edmund Pendleton

Edmund Pendleton (September 9, 1721 – October 23, 1803) was an American planter, politician, lawyer, and judge. He served in the Virginia legislature before and during the American Revolutionary War, rising to the position of speaker. Pendleto ...

, these "federalists who are for amendments" criticized the absence of a

bill of rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

and worried about surrendering taxation powers to the central government. After Madison reversed himself and promised to pass a bill of rights, the Virginia convention ratified the constitution by a narrow vote, though Monroe himself voted against it. Virginia was the tenth state to ratify the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

, and all thirteen states eventually ratified the document.

Senator

Henry and other anti-federalists hoped to elect a Congress that would amend the Constitution to take away most of the powers it had been granted ("commit suicide on

tsown authority", as Madison put it). Henry recruited Monroe to run against Madison for a House seat in the

First Congress, and he had the Virginia legislature

draw

Draw, drawing, draws, or drawn may refer to:

Common uses

* Draw (terrain), a terrain feature formed by two parallel ridges or spurs with low ground in between them

* Drawing (manufacturing), a process where metal, glass, or plastic or anything ...

a

congressional district

Congressional districts, also known as electoral districts and legislative districts, electorates, or wards in other nations, are divisions of a larger administrative region that represent the population of a region in the larger congressional bod ...

designed to elect Monroe. During the campaign, Madison and Monroe often traveled together, and the election did not destroy their friendship. In

the election for Virginia's Fifth District, Madison prevailed over Monroe, taking 1,308 votes compared to Monroe's 972 votes. Following his defeat, Monroe returned to his legal duties and developed his farm in Charlottesville. After the death of

Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

William Grayson

William Grayson (1742 – March 12, 1790) was a planter, lawyer and statesman from Virginia. After leading a Virginia regiment in the Continental Army, Grayson served in the Virginia House of Delegates before becoming one of the first two U ...

in 1790, Virginia legislators elected Monroe to serve the remainder of Grayson's term.

During the

presidency of George Washington

The presidency of George Washington began on April 30, 1789, when Washington was inaugurated as the first president of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1797. Washington took office after the 1788–1789 presidential election, the na ...

, U.S. politics became increasingly polarized between the supporters of Secretary of State Jefferson and

the

Federalists

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

, led by Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton. Monroe stood firmly with Jefferson in opposing Hamilton's strong central government and strong executive. The

Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

coalesced around Jefferson and Madison, and Monroe became one of the fledgling party's leaders in the Senate. He also helped organize opposition to

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

in the

1792

election, though Adams defeated

George Clinton to win re-election as vice president. As the 1790s progressed, the

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

came to dominate U.S. foreign policy, with British and French raids both threatening U.S. trade with Europe. Like most other Jeffersonians, Monroe supported the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, but Hamilton's followers tended to sympathize more with Britain. In 1794, hoping to find a way to avoid war with both countries, Washington appointed Monroe as his

minister (ambassador) to France. At the same time, he appointed the anglophile Federalist

John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the first ...

as his

minister to Britain.

Minister to France

After arriving in France, Monroe addressed the

National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

, receiving a standing ovation for his speech celebrating

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

. He experienced several early diplomatic successes, including the protection of U.S. trade from French attacks. He also used his influence to win the release of

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

and

Adrienne de La Fayette

Marie Adrienne Françoise de Noailles, Marquise de La Fayette (2 November 1759 – 25 December 1807), was a French marchioness. She was the daughter of Jean de Noailles and Henriette Anne Louise d'Aguesseau, and married Gilbert du Motier, Marq ...

, the wife of the Marquis de Lafayette. Months after Monroe arrived in France, the U.S. and Great Britain concluded the

Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

, outraging both the French and Monroe—not fully informed about the treaty prior to its publication. Despite the undesirable effects of the Jay Treaty on Franco-American relations, Monroe won French support for U.S. navigational rights on the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

—the mouth of which was controlled by

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

—and in 1795 the U.S. and Spain signed

Pinckney's Treaty

Pinckney's Treaty, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, was signed on October 27, 1795 by the United States and Spain.

It defined the border between the United States and Spanish Florida, and guaranteed the United S ...

. The treaty granted the U.S. limited rights to use the port of

.

Washington decided Monroe was inefficient, disruptive, and failed to safeguard the national interest. He recalled Monroe in November 1796. Returning to his home in Charlottesville, he resumed his dual careers as a farmer and lawyer. Jefferson and Madison urged Monroe to run for Congress, but Monroe chose to focus on state politics instead.

In 1798 Monroe published ''A View of the Conduct of the Executive, in the Foreign Affairs of the United States: Connected with the Mission to the French Republic, During the Years 1794, 5, and 6 ''. It was a long defense of his term as Minister to France. He followed the advice of his friend Robert Livingston who cautioned him to "repress every harsh and acrimonious" comment about Washington. However, he did complain that too often the U.S. government had been too close to Britain, especially regarding the Jay Treaty. Washington made notes on this copy, writing, "The truth is, Mr. Monroe was cajoled, flattered, and made to believe strange things. In return he did, or was disposed to do, whatever was pleasing to that nation, reluctantly urging the rights of his own."

Confrontations and strife with Alexander Hamilton

In November 1792,

James Reynolds and Jacob Clingman were arrested for counterfeiting and speculating in Revolutionary War veterans' unpaid back wages. Then-Senator Monroe and congressmen

Frederick Muhlenberg

Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg (; January 1, 1750 – June 4, 1801) was an American minister and politician who was the first Speaker of the United States House of Representatives and the first Dean of the United States House of Represen ...

and

Abraham Venable investigated the charges. They found that

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

had been making payments to James Reynolds, and suspected Hamilton was involved in the crimes. They asked him about it, and Hamilton denied involvement in the financial crimes, but admitted that he'd made payments to Reynolds, and explained he'd had an affair with Reynolds' wife,

Maria

Maria may refer to:

People

* Mary, mother of Jesus

* Maria (given name), a popular given name in many languages

Place names Extraterrestrial

* 170 Maria, a Main belt S-type asteroid discovered in 1877

* Lunar maria (plural of ''mare''), large, ...

. James Reynolds had found out and was blackmailing him. He offered letters to prove his story. The investigators immediately dropped the matter, and Monroe promised Hamilton he would keep the matter private.

Jacob Clingman told Maria about the claim she'd had an affair with Hamilton, and she denied it, claiming the letters had been forged to help cover up the corruption. Clingman went to Monroe about this. Monroe added that interview to his notes, and sent the entire set to a friend, possibly

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, for safekeeping. Unfortunately, the secretary who was involved in managing the notes of the investigation made copies and gave them to scandal writer

James Callender.

Five years later, shortly after Monroe was recalled from France, Callender published accusations against Hamilton based on those notes. Hamilton and his wife thought this was retaliation on the part of Monroe for the recall, and confronted him via letter. In a subsequent meeting between the two of them, where Hamilton had suggested each bring a "second", Hamilton accused Monroe of lying, and challenged him to a duel. While such challenges were usually hot air, in this case Monroe replied "I am ready, get your pistols." Their seconds interceded, and an arrangement was made to give Hamilton documentation on what had occurred with the investigation.

Hamilton was not satisfied with the subsequent explanations, and at the end of an exchange of letters the two were threatening duels, again. Monroe chose

Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805. Burr's legacy is defined by his famous personal conflict with Alexand ...

as his second. Burr worked as a negotiator between the two parties, believing they were both being "childish", and eventually helped settle matters.

Governor of Virginia and diplomat (1799–1802, 1811)

Governor of Virginia

On a party-line vote, the Virginia legislature elected Monroe as

Governor of Virginia

The governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia serves as the head of government of Virginia for a four-year term. The incumbent, Glenn Youngkin, was sworn in on January 15, 2022.

Oath of office

On inauguration day, the Governor-elect takes th ...

in 1799. He would serve as governor until 1802. The constitution of Virginia endowed the governor with very few powers aside from commanding the militia when the Assembly called it into action. But Monroe used his stature to convince legislators to enhance state involvement in transportation and education and to increase training for the militia. Monroe also began to give

State of the Commonwealth addresses to the legislature, in which he highlighted areas in which he believed the legislature should act. Monroe also led an effort to create the state's first

penitentiary

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, correcti ...

, and imprisonment replaced other, often harsher, punishments. In 1800, Monroe called out the state militia to suppress

Gabriel's Rebellion, a

slave rebellion originating on a plantation six miles from the capital of Richmond. Gabriel and 27 other enslaved people who participated were all hanged for treason. As Governor, Monroe secretly worked with President Thomas Jefferson to secure a location where free and enslaved African Americans suspected of "conspiracy, insurgency, Treason, and rebellion" would be permanently banished.

Monroe thought that foreign and Federalist elements had created the

Quasi War

The Quasi-War (french: Quasi-guerre) was an undeclared naval war fought from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States. The ability of Congress ...

of 1798–1800, and he strongly supported

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

's candidacy for president in

1800. Federalists were likewise suspicious of Monroe, some viewing him at best as a French dupe and at worst a traitor. With the power to appoint election officials in Virginia, Monroe exercised his influence to help Jefferson win Virginia's

presidential electors

The United States Electoral College is the group of presidential electors required by the Constitution to form every four years for the sole purpose of appointing the president and vice president. Each state and the District of Columbia appo ...

. He also considered using the Virginia militia to force the outcome in favor of Jefferson. Jefferson won the 1800 election, and he appointed Madison as his Secretary of State. As a member of Jefferson's party and the leader of the largest state in the country, Monroe emerged as one of Jefferson's two most likely successors, alongside Madison.

Louisiana Purchase and Minister to Great Britain

Shortly after the end of Monroe's gubernatorial tenure, President Jefferson sent Monroe back to France to assist Ambassador

Robert R. Livingston

Robert Robert Livingston (November 27, 1746 (Old Style November 16) – February 26, 1813) was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat from New York, as well as a Founding Father of the United States. He was known as "The Chancellor", afte ...

in negotiating the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

. In the 1800

Treaty of San Ildefonso, France had acquired the territory of

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

from Spain; at the time, many in the U.S. believed that France had also acquired

West Florida

West Florida ( es, Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former S ...

in the same treaty. The American delegation originally sought to acquire West Florida and the city of

, which controlled the trade of the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. Determined to acquire New Orleans even if it meant war with France, Jefferson also authorized Monroe to form an alliance with the British if the French refused to sell the city.

Meeting with

François Barbé-Marbois

François Barbé-Marbois, marquis de Barbé-Marbois (31 January 1745 – 12 February 1837) was a French politician.

Early career

Born in Metz, where his father was director of the local mint, Barbé-Marbois tutored the children of the Marquis d ...

, the French foreign minister, Monroe and Livingston agreed to purchase the entire territory of Louisiana for $15 million; the purchase became known as the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

. In agreeing to the purchase, Monroe violated his instructions, which had only allowed $9 million for the purchase of New Orleans and West Florida. The French did not acknowledge that West Florida remained in Spanish possession, and the United States would claim that France had sold West Florida to the United States for several years to come. Though he had not ordered the purchase of the entire territory, Jefferson strongly supported Monroe's actions, which ensured that the United States would continue to expand to the West. Overcoming doubts about whether the Constitution authorized the purchase of foreign territory, Jefferson won congressional approval for the Louisiana Purchase, and the acquisition doubled the size of the United States. Monroe would travel to Spain in 1805 to try to win the cession of West Florida, but, with the support of France, Spain refused to consider relinquishing the territory.

After the resignation of

Rufus King, Monroe was appointed as the

ambassador to Great Britain in 1803. The greatest issue of contention between the United States and Britain was that of the

impressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice. European navies of several nations used forced recruitment by various means. The large size of ...

of U.S. sailors. Many U.S. merchant ships employed British seamen who had deserted or dodged conscription, and the British frequently impressed sailors on U.S. ships in hopes of quelling their manpower issues. Many of the sailors they impressed had never been British subjects, and Monroe was tasked with persuading the British to stop their practice of impressment. Monroe found little success in this endeavor, partly due to Jefferson's alienation of the British minister to the United States,

Anthony Merry

Anthony Merry (2 August 1756 – 14 June 1835) was a British diplomat.

Biography

The son of a London wine merchant, Anthony Merry served in various diplomatic posts in Europe between 1783 and 1803, holding mostly consular positions. In 1803 he ...

. Rejecting Jefferson's offer to serve as the first governor of

Louisiana Territory

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805, until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed the Missouri Territory. The territory was formed out of the ...

, Monroe continued to serve as ambassador to Britain until 1807.

In 1806 he negotiated the

Monroe–Pinkney Treaty

The Monroe–Pinkney Treaty was a treaty drawn up in 1806 by diplomats of the United States and Great Britain to renew the 1795 Jay Treaty. As it was rejected by President Thomas Jefferson, it never took effect. The treaty was negotiated by the m ...

with Great Britain. It would have extended the Jay Treaty of 1794 which had expired after ten years. Jefferson had fought the Jay Treaty intensely in 1794–95 because he felt it would allow the British to subvert

American republicanism

The values, ideals and concept of republicanism have been discussed and celebrated throughout the history of the United States. As the United States has no formal hereditary ruling class, ''republicanism'' in this context does not refer to a ...

. The treaty had produced ten years of peace and highly lucrative trade for American merchants, but Jefferson was still opposed. When Monroe and the British signed the new treaty in December 1806, Jefferson refused to submit it to the Senate for ratification. Although the treaty called for ten more years of trade between the United States and the British Empire and gave American merchants guarantees that would have been good for business, Jefferson was unhappy that it did not end the hated British practice of impressment, and refused to give up the potential weapon of commercial warfare against Britain. The president made no attempt to obtain another treaty, and as a result, the two nations drifted from peace toward the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

. Monroe was severely pained by the administration's repudiation of the treaty, and he fell out with Secretary of State James Madison.

1808 election and the Quids

On his return to Virginia in 1807, Monroe received a warm reception, and many urged him to run in the

1808 presidential election. After Jefferson refused to submit the Monroe-Pinkney Treaty, Monroe had come to believe that Jefferson had snubbed the treaty out of the desire to avoid elevating Monroe above Madison in 1808. Out of deference to Jefferson, Monroe agreed to avoid actively campaigning for the presidency, but he did not rule out accepting a draft effort.

The Democratic-Republican Party was increasingly factionalized, with "

Old Republicans" or "Quids" denouncing the Jefferson administration for abandoning what they considered to be true republican principles. The Quids tried to enlist Monroe in their cause. The plan was to run Monroe for president in the 1808 election in cooperation with the

Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a Conservatism in the United States, conservative political party which was the first political party in the United States. As such, under Alexander Hamilton, it dominated the national government from 1789 to 1801.

De ...

, which had a strong base in New England.

John Randolph of Roanoke

John Randolph (June 2, 1773May 24, 1833), commonly known as John Randolph of Roanoke,''Roanoke'' refers to Roanoke Plantation in Charlotte County, Virginia, not to the city of the same name. was an American planter, and a politician from Virg ...

led the Quid effort to stop Jefferson's choice of Madison. The regular Democratic-Republicans overcame the Quids in the nominating caucus, kept control of the party in Virginia, and protected Madison's base. Monroe did not publicly criticize Jefferson or Madison during Madison's campaign against Federalist

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, but he refused to support Madison. Madison defeated Pinckney by a large margin, carrying all but one state outside of New England. Monroe won 3,400 votes in Virginia, but received little support elsewhere.

After the election Monroe quickly reconciled with Jefferson, but their friendship endured further strains when Jefferson did not promote Monroe's candidacy to Congress in 1809. Monroe did not speak with Madison until 1810.

[ Returning to private life, he devoted his attentions to farming at his Charlottesville estate.

]

Secretary of State and Secretary of War (1811–1817)

Madison administration

Monroe returned to the Virginia House of Burgesses and was elected to another term as governor in 1811, but served only four months. In April 1811, Madison appointed Monroe as Secretary of State in hopes of shoring up the support of the more radical factions of the Democratic-Republicans.

Monroe returned to the Virginia House of Burgesses and was elected to another term as governor in 1811, but served only four months. In April 1811, Madison appointed Monroe as Secretary of State in hopes of shoring up the support of the more radical factions of the Democratic-Republicans.[ Madison also hoped that Monroe, an experienced diplomat with whom he had once been close friends, would improve upon the performance of the previous Secretary of State, Robert Smith. Madison assured Monroe that their differences regarding the Monroe-Pinkney Treaty had been a misunderstanding, and the two resumed their friendship. The Senate voted unanimously (30–0) to confirm him. On taking office, Monroe hoped to negotiate treaties with the British and French to end the attacks on American merchant ships. While the French agreed to reduce the attacks and release seized American ships, the British were less receptive to Monroe's demands. Monroe had long worked for peace with the British, but he came to favor war with Britain, joining with "war hawks" such as Speaker of the House ]Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

. With the support of Monroe and Clay, Madison asked Congress to declare war upon the British, and Congress complied on June 18, 1812, thus beginning the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

.

The war went very badly, and the Madison administration quickly sought peace, but were rejected by the British. The U.S. Navy did experience several successes after Monroe convinced Madison to allow the Navy's ships to set sail rather than remaining in port for the duration of the war. After the resignation of Secretary of War William Eustis

William Eustis (June 10, 1753 – February 6, 1825) was an early American physician, politician, and statesman from Massachusetts. Trained in medicine, he served as a military surgeon during the American Revolutionary War, notably at the Bat ...

, Madison asked Monroe to serve in dual roles as Secretary of State and Secretary of War, but opposition from the Senate limited Monroe to serving as acting Secretary of War until Brigadier General John Armstrong won Senate confirmation. Monroe and Armstrong clashed over war policy, and Armstrong blocked Monroe's hopes of being appointed to lead an invasion of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. As the war dragged on, the British offered to begin negotiations in Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded in ...

, and the United States sent a delegation led by John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

to conduct negotiations. Monroe allowed Adams leeway in setting terms, so long as he ended the hostilities and preserved American neutrality.

When the British burned the U.S. Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill at ...

and the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

on August 24, 1814, Madison removed Armstrong as Secretary of War and turned to Monroe for help, appointing him Secretary of War on September 27. Monroe resigned as Secretary of State on October 1, 1814, but no successor was ever appointed and thus from October 1814 to February 28, 1815, Monroe effectively held both Cabinet posts. Now in command of the war effort, Monroe ordered General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

to defend against a likely attack on by the British, and he asked the governors of nearby states to send their militias to reinforce Jackson. He also called on Congress to draft an army of 100,000 men, increase compensation to soldiers, and establish a new national bank

In banking, the term national bank carries several meanings:

* a bank owned by the state

* an ordinary private bank which operates nationally (as opposed to regionally or locally or even internationally)

* in the United States, an ordinary p ...

to ensure adequate funding for the war effort. Months after Monroe took office as Secretary of War, the war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

. The treaty resulted in a return to the status quo ante bellum, and many outstanding issues between the United States and Britain remained. But Americans celebrated the end of the war as a great victory, partly due to the news of the treaty reaching the United States shortly after Jackson's victory in the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the French ...

. With the end of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

in 1815, the British also ended the practice of impressment. After the war, Congress authorized the creation of a national bank in the form of the Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ac ...

.

Election of 1816

Monroe decided to seek the presidency in the 1816 election, and his war-time leadership had established him as Madison's heir apparent. Monroe had strong support from many in the party, but his candidacy was challenged at the 1816 Democratic-Republican congressional nominating caucus The congressional nominating caucus is the name for informal meetings in which American congressmen would agree on whom to nominate for the Presidency and Vice Presidency from their political party.

History

The system was introduced after George W ...

. Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford

William Harris Crawford (February 24, 1772 – September 15, 1834) was an American politician and judge during the early 19th century. He served as US Secretary of War and US Secretary of the Treasury before he ran for US president in the 1824 ...

had the support of numerous Southern and Western Congressmen, while Governor Daniel D. Tompkins

Daniel D. Tompkins (June 21, 1774 – June 11, 1825) was an American politician. He was the fifth governor of New York from 1807 to 1817, and the sixth vice president of the United States from 1817 to 1825.

Born in Scarsdale, New York, Tompkins ...

was backed by several Congressmen from New York. Crawford appealed especially to many Democratic-Republicans who were wary of Madison and Monroe's support for the establishment of the Second Bank of the United States. Despite his substantial backing, Crawford decided to defer to Monroe on the belief that he could eventually run as Monroe's successor, and Monroe won his party's nomination. Tompkins won the party's vice presidential nomination. The moribund Federalists nominated Rufus King as their presidential nominee, but the party offered little opposition following the conclusion of a popular war that they had opposed. Monroe received 183 of the 217 electoral votes, winning every state but Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Delaware. Since he previously served as an officer of the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

during the Revolutionary War and as a delegate

Delegate or delegates may refer to:

* Delegate, New South Wales, a town in Australia

* Delegate (CLI), a computer programming technique

* Delegate (American politics), a representative in any of various political organizations

* Delegate (Unit ...

in the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

, he became the last president who was a Founding Father

The following list of national founding figures is a record, by country, of people who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e. ...

.

Presidency (1817–1825)